A column of Mark V tanks moving up to the front. The Battle of Amiens saw the largest concentration of tanks ever assembled during the First World War.

General Rawlinson’s offensive at Amiens in the summer of 1918 was based on a bold gamble. This was at a crucial moment in the war when it had been finally accepted by the moribund infantry commanders that the tank represented the key to eventual victory. The Allies were encouraged by the French counter-attack on the Marne when using a swarm of tanks they had achieved startling success. This had come at a cost amounting to 184 heavy tanks, some 57 per cent of the total. Nonetheless, it was decided to commit every single British tank brigade to the attack at Amiens, except for the 1st that at the time was converting from the Mark IV to the new Mark V tank. If anything went wrong or losses were too heavy at Amiens, it could result in the British Army losing its tank fleet in one go.

The Allies’ sledgehammer force at Amiens was provided by three whole tank brigades from the British Tank Corps totalling eleven tank battalions. It comprised the largest concentration of tanks ever assembled during the First World War – numbering 324 heavy tanks and ninety-six medium tanks in the British sector with seventy-two light tanks in the French. Supporting them were an additional 120 supply tanks and twenty-two gun-carrier tanks, giving a total of 634 tanks committed to the battle. It was notable because of their heavy losses on the Marne that the French infantry had to go over the top largely without tank support.

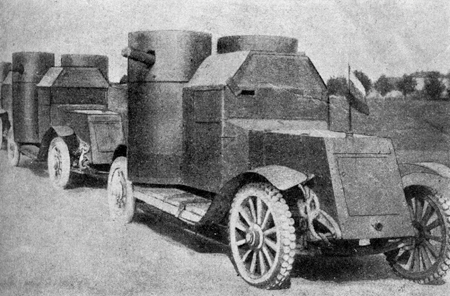

Two other ‘armoured’ units were to be involved. Firstly the 17th Armoured Car Battalion, equipped with sixteen vehicles, had only come into existence in April 1918. This Tank Corps formation was issued with Austin armoured cars which had originally been built for export to Russia. The Russian Army had ordered three batches of Austins before the Revolution finally but an end to any further deliveries. Featuring double turrets they were armed with the Hotchkiss M1914 machine gun rather than Vickers or Maxim guns in British service. It was a unique unit within the Tank Corps as the RNAS had handed its armoured cars over the Army’s Machine Gun Corps in the summer of 1915 to form the Light Armoured Motor Batteries. Secondly there were two Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigades. They operated lightly armoured, open-topped trucks designed to move machine guns, mortars and infantry about. Essentially these operated as weapons carriers and lightly-armoured personnel carriers rather than true armoured fighting vehicles.

At Amiens Rawlinson, now an enthusiast of the tank, followed the example set by Monash and deployed the largest practicable force of armour and the smallest practicable force of infantry – some eight assault divisions. North to south in Rawlinson’s 4th Army’s sector lay the British 3rd Corps, the Australian Corps and the Canadian Corps. The 10th Tank Battalion was assigned to 3rd Corps while the 5th and 4th Tank Brigades (each with four tank battalions) were with the Australians and Canadian respectively. The Australian Corps was also supported by the 17th Armoured Car Battalion. The 3rd Tank Brigade, with two battalions of Whippets, acted in support of the cavalry units. South of the Canadians was General Debeney’s French 1st Army with three corps facing Moreuil.

The attack opened on 8 August 1918. At 0420 Monash recalled: ‘A great illumination lights up the Eastern horizon: and instantly the whole complex organization, extending far back to areas almost beyond earshot of the guns, begins to move forward: everyman, every unit, every vehicle and every tank on the appointed tasks and to their designated goals, sweeping on relentlessly and irresistibly.’ The exhausted Germans were taken completely by surprise. Rawlinson’s 4th Army advanced over seven miles in less than nine hours. By early afternoon 4th Army and the French 1st Army had taken their initial objectives of Warfusée and Moreuil, followed by Bayonvillers, Guilleaucourt and Hangest.

Regarding the Battle of Amiens Lloyd George recorded in his memoirs: ‘Four hundred and fifteen fighting tanks went over the top at zero hour that morning, and in all the engagements of the succeeding days, tanks played their part smashing a way for the infantry, crashing through entanglements, sweeping across trenches, everywhere scattering and stampeding the enemy forces, circumventing machine gun nests and receiving as little hurt from their sting as from ant-heaps in the path of a rhinoceros.’

Having learned the lesson of Cambrai, a mixed force of armour cars, cavalry and Whippets was assembled as the follow-up force to immediately exploit the breakthrough. Co-operation between the cavalry and tanks was poor, but towed across No Man’s Land by the tanks the armoured cars were unleashed in the German rear. In the Morcourt valley the armoured cars and the tanks turned the Germans’ defences, despite an anti-aircraft gun acting in an anti-tank role.

That first day the Tank Corps losses were very heavy. By 9 August just 145 tanks were available, the following day sixty-three and by the 11th the number was down to thirty-eight. By this stage the battle had lost its momentum. The lurching British Mark IV did not make for a stable gun platform, nor did its restricted vision and poor field of fire help. In reality few German soldiers were actually killed by British tank fire. None of this mattered, however, as the tank had helped smash German morale once and for all. Ludendorff and his generals were shaken by this dramatic turn of events.

Unfortunately the tanks were simply not fast or mechanically reliable enough to keep up with the retreating Germans. Likewise the cavalry could do little in the face of German machine-gun and artillery fire. Nonetheless, new innovations in armoured warfare were tried. For example night attacks were conducted in coordination with aircraft. Also a number of tank-versus-tank encounters took place continued right until the end of the war.

Although Ludendorff was able to stabilize the front and hold any further Allied advances the damage was done. German morale was irretrievably broken. Ludendorff belatedly recognized that the tank was a game-changer. On 30 September 1918 he reported, ‘It is not, however, the low strengths of our divisions which make our position serious but rather the tanks which appear by surprise in ever increasing numbers. . . . Owing to the effect of the tanks our operations on the Western Front have now practically assumed the character of a game of chance.’

Not all Germans were prepared to accept that the tank was the reason for their defeat. If anything, Amiens showed just how vulnerable the tank was to direct artillery fire. General von der Marwitz argued: ‘Tanks are no bogey for the front line troops who have artillery in close support. For instance, a battery-sergeant-major with his own gun destroyed 4 tanks; one battery destroyed 14; and a single division in one day 40. In another instance, a smart corporal climbed onto a tank and put the crew out of action with his revolver, firing through the aperture. A lance corporal was successful in putting a tank out of action with a hand grenade.’ Despite such bravery the Germans acknowledged Amiens as a British victory and called 8 August the ‘Black Day’.

Throughout the summer Foch launched a major offensive along the entire front with tanks once again playing their part. In the early autumn, in a series of wellexecuted offensives led by tanks, the American Army cleared the Argonne to the south-east of Reims and the British broke out beyond Le Cateau, although the Germans were able to fall back in an orderly manner. Nonetheless, time was running out for the German military as they sought to avoid the inevitable.

A column of Mark V tanks moving up to the front. The Battle of Amiens saw the largest concentration of tanks ever assembled during the First World War.

Armoured trucks of the Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigades. One of the crew is wearing a captured German helmet. Serving with the Canadian Independent Force, these units provided mobile fire support and acted as armoured personnel carriers.

At Amiens the Tank Corps also fielded the 17th Armoured Car Battalion equipped with Austin armoured cars originally intended for the Russian Army.

A Canadian adorns a supporting tank with a maple leaf ready for the attack.

A British 18-pounder field gun deploying to support the tanks. The bulk of the tanks were assigned to the Australian and Canadian Corps. Only a single battalion served with the British 3rd Corps.

German prisoners pass a Mark V tank on the Amiens-Roye Road on 8 August 1918.

Canadians conferring with a tank crew whose tank has thrown a track. A passing French artillery crew look on with interest.

Canadian troops and their tanks passing German prisoners on 9 August 1918.

Troops taking a break by a Mark V tank that slipped off a railway embankment. Infantry were first carried into battle in tanks at Amiens in 1918. The Mark V* provided extra interior space but was not terribly successful.

The crew of this Canadian armoured truck were caught by enemy fire. It appears, judging from the empty ammo belts and empty ammo boxes, that they ran out of ammunition.

New Zealanders with a captured German Mauser M1918 anti-tank rifle.

Canadian troops resting by an unarmed Renault signal tank on the Arras-Cambrai road on 1 September 1918.

Observation tanks on a flooded road.