April 22, 2002.

The Indian Ocean.

On board the United States Aircraft Carrier Thomas Jefferson. 9S, 92E. Speed 30.

THEY HAD WAVED HIM OFF TWICE NOW. AND EACH TIME Lieutenant William R. Howell had eased open the throttle of his big F-14 interceptor/attack Tomcat and climbed away to starboard, watching the speed needle slide smoothly from 150 knots to 280 knots. The acceleration was almost imperceptible, but in seconds the lieutenant saw the six-story island of the carrier turn into a half-inch-high black thimble against the blue sky.

The deep Utah drawl of the Landing Signal Officer standing on the carrier stern was still calm: “Tomcat two-zero-one, we still have a fouled deck—gotta wave you off one more time—just an oil leak—this is not an emergency, repeat not an emergency.”

Lieutenant Howell spoke quietly and slowly: “Tomcat two-zero-one. Roger that. I’m taking a turn around. Will approach again from twelve miles.” He eased the fighter plane’s nose up, just a fraction, and he felt his stomach tighten. It was never more than a fleeting feeling, but it always brought home the truth, that landing any aircraft at sea on the narrow, angled, 750-foot-long, pitching landing area remained a life-or-death test of skill and nerve for any pilot. It took most rookies a couple of months to stop their knees shaking after each landing. Pilots short of skill, or nerve, were normally found working on the ground, driving freight planes, or dead. He knew that there were around twenty plane-wrecking crashes on U.S. carriers each year.

From the rear seat, the radar-intercept officer (RIO), Lieutenant Freddie Larsen, muttered, “Shit. There’s about a hundred of ’em down there, been clearing up an oil spill for a half hour—what the hell’s going on?” Neither aviator was a day over twenty-eight years old, but already they had perfected the Navy flier’s nonchalance in the face of instant death at supersonic speed. Especially Howell.

“Dunno,” he said, gunning the Tomcat like a bullet through the scattered low clouds whipping past this monster twin-tailed warplane, now moving at almost five miles every minute. “Did y’ever see a big fighter jet hit an oil pool on a carrier deck?”

“Uh-uh.”

“It ain’t pretty. If she slews out off a true line you gotta real good chance of killing a lot of guys. ’Specially if she hits something and burns, which she’s damn near certain to do.”

“Try to avoid that, willya?”

Freddie felt the Tomcat throttle down as Howell banked away to the left. He felt the familiar pull of the slowing engines, worked his shoulders against the yaw of the aircraft, like the motorcycle rider he once had been.

The F-14 is not much more than a motorbike with a sixty-four-foot wingspan anyway. Unexpectedly sensitive to the wind at low speed, two rock-hard seats, no comfort, and an engine with the power to turn her into a mach-2 rocketship—1,400 knots, no sweat, out there on the edge of the U.S. fighter pilot’s personal survival envelope.

Still holding the speed down to around 280 knots, Howell now took a long turn, the Tomcat heeled over at an angle of almost ninety degrees, the engines screaming behind him, as if the sound was trying to catch and swallow him. Up ahead he could no longer see the carrier because of the intermittent white clouds obscuring his vision and casting dark shadows on the blue water. Below the two fliers was one of the loneliest seaways on earth, the 3,500-mile stretch of the central Indian Ocean between the African island of Madagascar and the rock-strewn western coast of Sumatra.

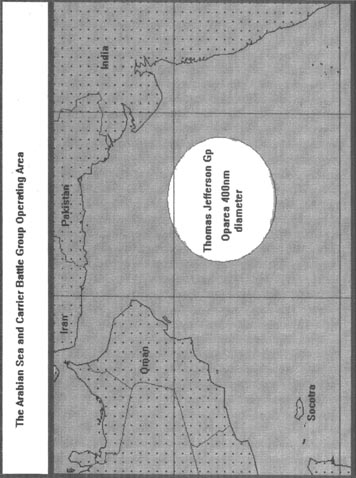

The U.S. carrier and its escorts, forming a complete twelve-ship Battle Group including two nuclear-powered submarines, were steaming toward the American Naval base on Diego Garcia, the tiny atoll five hundred miles south of the equator, which represents the only safe Anglo-American haven in the entire area.

This was a real U.S. Battle Group seascape, a place where the most beady-eyed admirals and their staff “worked up” new missile systems, new warships, and endlessly catapulted their ace Naval aviators off the flight deck—zero to 168 knots in 2.1 seconds. This was not a spot for the faint-hearted. This was a simulated theater of war, designed strictly for the very best the nation could produce…men who possessed what Tom Wolfe immortally labeled “the right stuff.” Everyone served out here for six interminable months at a time.

Lieutenant Howell, losing height down to 1,200 feet, spoke again to the carrier’s flight controllers. “Tower, this is Tomcat two-zeroone at eight miles. Coming in again.” His words were few, and again the jet fighter began to ease down, losing height, the engines throttling marginally off the piercing high-C shriek which would splinter a shelf of wineglasses. Howell, insulated behind his goggles and earphones, searched the horizon for the hundred-thousand-ton aircraft carrier.

His intercom crackled. “Roger, Tomcat two-zero-one. Your deck is cleared for landing now—gotcha visual…come on in, watch your altitude, and check your lineup. Wind’s gusting at thirty knots out of the southwest. We’re still right into it. You’re all set.”

“Roger, Tower…six miles.”

All Navy and Air Force pilots have a special, relaxed, aw-shucks way of imparting news from these high-speed fighter aircraft, some say copied directly from America’s most famous combat ace, General Chuck Yeager, the first test pilot to break the sound barrier in his supersecret Bell X-1 in 1947.

Talking to the tower, almost every young Navy flier affects some kind of a West Virginia country boy drawl, precisely how they imagine General Yeager might have put it, real slow, ice-calm in the face of disaster. “Gotta little flameout on the ole starboard engine, jest gonna cut the power out there, bring her in on one. Y’all wanna move the flight deck over a coupla ticks, gimme a better shot in the crosswind. It ain’t a problem.”

Lieutenant William R. Howell imitated the general “better’n any of ’em.” And easier. Because he was not really Lieutenant William R. Howell, anyway. He was Billy-Ray Howell, whose dad, an ex–coal miner and Southern Methodist, now kept the general store back in the same hometown as Chuck Yeager—up in the western hollows of the Appalachian Mountains, Hamlin, a place of less than a thousand souls, right on the Mud River, close to the eastern Kentucky border in Lincoln County. Like Chuck Yeager, Billy-Ray talked about the ‘hollers,’ fished the Mud River, was the son of a man who had shot a few bears in his time, “cain’t hardly wait to git home, see my dad.”

When he had the stick of an F-14 in his hand, Billy-Ray Howell was General Yeager. He thought like him, talked like him, and acted as he knew the general would in any emergency. No matter that big Chuck had retired to live in California. As far as Billy-Ray was concerned he and Chuck Yeager formed an unspoken, mystical West Virginia partnership in the air, and he, Billy-Ray, was a kind of heir-apparent. In his view, the old country way of life out among the hickory and walnut tree woods of Lincoln County gave a kid a tough center. And he was “damn near sure Mr. Yeager would agree with that.”

The strategy had paid off too. Billy-Ray had achieved his schoolboy ambition to become a Naval aviator. Years of study, years of training, had seen him close to the top of every class he had ever been in. Everyone in Naval aviation knew that young Billy-Ray Howell was going onward and upward. They had ever since he first earned his engineering degree at the U.S. Naval Academy.

No one was surprised by how good he was when he began his jet fighter training, pushing the old T2 Buckeyes around the skies above Whiting Field, east of Pensacola, in northwest Florida.

And now the voice coming into the flight-control area was nearly identical to that of General Yeager, the steady “up-holler” tone, betraying no urgency: “Tower, Tomcat two-zero-one, four miles. I got somethin’ gone kinda weird on me, right here…landin’ gear warning light’s jes’ flickin’ some. Didn’t feel the wheels lock down. But it might be somethin’s jes’ wrong with th’ole lightbulb.”

“Tower to Tomcat two-zero-one. Roger that. Continue on in and make a pass right down the deck at about fifty feet, two hundred knots. That way the guys can take a close look at the undercarriage.”

“Roger, tower…comin’ on in.”

Out on the exposed and windswept carrier deck, the Landing Signal Officer radioed instructions to the pilot and could see that Tomcat 201 was about forty-five seconds out, a howling, twenty-ton brute of an aircraft, bucking along in the unpredictable gusts over the Indian Ocean, the pilot trying to hold her on a glide path two degrees above the horizontal. There was a big swell on the surface, and the whole ship, moving along at fifteen knots, was pitching through about three degrees, one and a half degrees either side of horizontal: that meant the ends, bow and stern, were moving through sixty feet vertically every thirty seconds. All incoming aircraft would have a hell of an approach into the strong, hot wind, and timing the moment of impact would test the deftness and proficiency of every pilot. That was with landing wheels.

The LSO, Lieutenant Rick Evans, a lanky fighter pilot out of Georgia, was now standing on the exposed port-quarter of the carrier. His binoculars were trained on Tomcat 201. And he could already see the landing wheels were not down—and the flaps weren’t down either. His mind was churning. He knew that Billy-Ray Howell was in trouble. Nonfunctioning landing gear have always been the flier’s nightmare, civil or military. But out here it was a hundred times worse.

A fighter plane does not come in along the near flat path followed by civil jetliners, which glide, and then “flare out” a few feet above mile-long runways. Out here there’s no time. And not much space. Navy fliers slam those twenty-two-ton Tomcats down at 160 knots, flying them right into the deck, hook down, praying for it to grab the wire.

The downward momentum on the landing wheels is astronomical. They are monster shock absorbers, built to kill the entire onrushing weight of the aircraft. If the hook misses, the pilot has one twentieth of a second to change his mind, to “do a bolter”—shove open the throttle and blast off over the bow, climbing away to starboard with the casual observation, “Comin’on in again.”

The slightest problem with the locking mechanism aborts the landing, and, almost without exception, writes off the aircraft. Because the Navy would rather ditch a $35 million jet, on its own, than kill two aviators who have cost $2 million apiece to train. They would also much prefer the aircraft to slam into the ocean, and avoid the terrible risk of a major fire on the flight deck, which a belly-down landing may cause. Not to mention the possible write-off of another forty parked planes, and possibly the entire ship if the fire gets to the millions of gallons of aircraft fuel.

Everyone on the flight deck knew that Billy-Ray and Freddie would almost certainly have to ditch the jet, and blast themselves out of the cockpit with the ejector, a dangerous and terrifying procedure, one which can cost any pilot an arm or a leg, or worse yet, his life. “Holy Christ,” said Lieutenant Evans, miserably.

By now the LSO and his team were all edging toward the deep, heavily padded “pit” into which they would dive for safety if Billy-Ray lost control and the Tomcat plummeted into the carrier’s stern. All fire crews were on red-alert. “Conn-Captain, four degrees right rudder. Steer two-one-zero. I want thirty knots minimum over the deck. Speed as required.”

Everyone could now hear the roar of the engines on the incoming Tomcat, and the bush telegraph of the carrier was working full tilt. Most everyone had a soft spot for Billy-Ray. He’d been married for only a year, and half the personnel of the Naval Air Base on the Pax River in Maryland had been at the wedding. His bride, Suzie Danford, was the tall, dark-haired daughter of Admiral Skip Danford. She’d met the curly-haired, dark-eyed Billy-Ray, with his coal-miner’s shoulders and sly smile, long before he had become one of the Navy’s elite fliers, while he was completing training at Pensacola.

And now she was alone in Maryland, waiting out the endless six months of his first tour of sea duty. Like all aviators’ wives, dreading the unexpected knock upon the door, dreading the stranger from the air base calling on the phone, the one who would explain that her Billy-Ray had punched a big hole in the Indian Ocean. And there was nothing melodramatic about any of it. About 20 percent of all Navy pilots die in the first nine years of their service. At the age of twenty-six, Suzie Danford Howell was no stranger to death. And the possibility of her own husband joining Jeff McCall, Charlie Rowland, and Dave Redland haunted her nights. Sometimes she thought it would all drive her crazy. But she tried to keep her fears silent.

She did not know, however, the mortal danger her husband was now in. There are virtually no procedures for landing gear failure. Nothing works, save for a touch of blind luck if the pilot can jolt down and then up, and the gears slam down and lock, putting out the warning light. But time is short. If that Tomcat F-14 runs out of gas it will drop like a twenty-ton slab of concrete and hit the long waves of the Indian Ocean like a meteorite…. “Billy-Ray Howell and Freddieare in trouble”…the word was sweeping through the carrier.

On the tower side of the flight deck, Ensign Jim Adams, a huge black man from South Boston, dressed in a big fluorescent yellow jacket, was talking on his radio phone to the hydraulics operators on the deck below who controlled the arresting wires, one of which would grab the Tomcat, slowing it down to zero speed in two seconds flat, heaving the aircraft to a halt. Big Jim, the duty Arresting Gear Officer, had already ordered the controls set to withstand the Tomcat’s fifty-thousand-pound force slamming into the deck at 160 knots precisely, with the pilot’s hand hard on the throttle in case the hook missed. But Jim knew the problem…“Billy-Ray Howell’s in big trouble up there.”

Big Jim loved Billy-Ray, a most unlikely duo on a big carrier, where aircrew tend to be a race apart. They talked about baseball endlessly, Jim because he believed he would have made a near-legendary first baseman for the Boston Red Sox, Billy-Ray because he had been a pretty good right-handed pitcher at Hamlin High. Next year they planned a jaunt to watch the Red Sox spring training for four days in Florida. Right now Big Jim wished only that he could check out and fix the hydraulics on the Tomcat’s landing gear, and he found himself whispering the age-old prayer of all carrier flight deck crew…“Please, please don’t let him die, please let him get out.”

Up on the bridge, Captain Carl Rheinegen was speaking to the senior LSO back on the stern. “Has he got a hydraulics malfunction? Do not land him. Hold him up and clear!”

Again the big waterproof phone clutched by Lieutenant Rick Evans crackled, and the incoming voice was still slow. “Tower, this is Tomcat two-zero-one. Still got some kinda screwup here. Tried to give her a few jolts. But it didn’t work. Light’s still on. I can cross the stern okay and come on by, but I don’t think the hydraulics are too good. I’d prefer to keep the speed at 250 and take her straight back up. Git a little air underneath. No real problem. Stick’s a little tough. But we got gas. Lemme know.”

And now the F-14 was thundering in toward the stern, twice as fast as an 80 mph Metroliner through New Jersey, and ten times as deafening. Too fast, but still with height. “Tower to Tomcat two-zero-one. Hit the throttle and pull right out, forget the pass. Repeat, forget the pass.”

“Roger that,” said Billy-Ray Howell carefully, and he slammed the throttle forward and hauled on the stick. But nothing much happened except for acceleration. She seemed to flatten out and then she was diving in toward the end of the flight deck, still with two Phoenix missiles under her wing. Enough to blow half the flight deck to bits. Still slow and easy, Billy-Ray drawled: “Tomcat two-zero-one, I’ll jest take a little jog to my left and git out over the portside.” And he watched through his deep-set eyes as the heaving flight deck roared up to meet him. He fought to stay aloft but the Tomcat now had a mind of its own. A bloody mind.

Rick Evans, watching the F-14 now hurtling toward the portside edge of the flight deck, snapped back into the phone: “Get out, Billy-Ray, hit it!”

For a split second Freddie Larsen thought his pilot might consider an ejection a sign of weakness or lack of cool. And he screamed for the first time in his flying career, “Punch it out, Billy-Ray, for Christ’s sake, punch it out!!”

The Tomcat ripped past the carrier’s mast, just as Lieutenant William R. Howell’s right fist banged the lever. The compacted-charge exploded beneath his seat and blew him head-first out of the cockpit. Freddie followed, point five of a second later, the violence of the two explosions rendering them both momentarily unconscious. Freddie came around first, saw the Tomcat crash about twenty feet off the carrier’s port bow, sending a spout of water fifty feet into the air, almost up to the flight deck.

But they were clear. When Billy-Ray came around, he saw his parachute canopy swinging above his head and the carrier’s surging, white stern wake beneath him. And even as he and Freddie hit the water, the Sea King helicopter was lifting off the roof of the carrier, in a roaring whirlwind of air. Flight deck crew were emerging from cover. All landing and takeoff operations were suspended, and down in the heaving sea, half-drowned despite his watertight survival suit, fighting for breath, Billy-Ray Howell could hear the God-sent voice of the rescue chief yelling through the loud-hailer: “Easy, guys, take it real easy; release the chutes and keep still, we’ll be right down.”

The big chopper came in. A nineteen-year-old sailor jumped straight out into the water with the lines, and made for the two stricken U.S. airmen. “You guys okay?” he asked. “We’re a whole lot better’n we would be still in the ole F-14,” said Billy-Ray. Thirty-five seconds later they were both winched up to safety, both trembling from shock, Freddie Larsen with a broken right arm, Billy-Ray with a gashed eyebrow and blood pouring down his face, which made his grin look a bit crooked.

The chopper came in to land on the starboard side of the deck. Three medics were there, plus stretcher bearers. Lieutenant Rick Evans was also trembling and he just kept saying over and over, “Gee, I’m just so sorry, guys. I’m just so sorry.”

There was a small but somber welcoming party for the two battered airmen. Big Jim Adams came rushing through the group, against every kind of Naval regulation, and he lifted Billy-Ray right out of the chopper, cradling him in his massive arms, saying: “Don’t you never damned die on me again, man, hear me?” Everyone could see the tears streaming down Big Jim’s face.

The medics then took over, giving both men a shot of painkiller, and strapping Billy-Ray and Freddie into the wheeled stretchers. And the whole procession, now about fourteen strong, all a bit shaken, headed for the elevators, bound together by the camaraderie of men who have looked into the face of death together.

Freddie spoke first: “You are a crazy prick, Billy-Ray. You shoulda hit the button fifteen seconds earlier.”

“Bullshit, Freddie. I had the timing right. If I’d punched out any earlier you’d probably be sittin’ up there on top of the mast right now.”

“Yeah, and one second later we’d both be sitting on the bottom of the fucking Indian Ocean.”

“Shit!” said Billy-Ray. “You’re an ungrateful sonofabitch. I jes’ saved your life. And you ain’t even my real problem. Do you realize Suzie’s gonna have a heart attack when she hears about this? Guess I’ll have to blame you.”

“This is unbelievable,” said Freddie, trying to smile, reaching out with his good arm to grasp his pilot’s still shaking hand. “Wanna do it again sometime!”

The loss of a big Tomcat fighter aircraft is generally regarded as a career-threatening occurrence. A scapegoat is a near essential in the U.S. Navy after a foul-up which costs Uncle Sam around $35 million. Both the captain and the admiral would have to answer for this, and they had a lot of questions. Was this pilot error? Was it flight deck error? Who had checked and serviced the aircraft before it came up on deck for its last journey? Had the officer in charge of the final check over, moments before takeoff, missed something? Was there any clue that the launching officer should have seen?

The preliminary report would be required in the Pentagon just as soon as it could be completed. And the official inquiry was convened instantly. Hydraulics experts were called in first. The officers would routinely talk to Billy-Ray and Freddie during the evening, in the carrier’s brilliantly equipped hospital, after the surgeons had set the young navigator’s arm.

None of the aviators believed the pilot had made any kind of mistake, and everyone knew that Lieutenant William R. Howell had hung in there until the last possible second in order to drive his two-hundred-knot time bomb safely out over the side of the ship. Senior officers would no doubt reach a sympathetic conclusion, but there would be real hard questions asked of the Maintenance Department and its specialist hydraulics engineers.

While the preliminary inquiry into the accident continued, the day to-day business of the U.S. Battle Group at sea also proceeded on schedule. Up on the Admiral’s Bridge, Captain Jack Baldridge, the Battle Group Operations Officer, was normally in charge, in the absence of the admiral himself. But right now he was in conference on the floor below, in the radar and electronics nerve center with the Tactical Action officer and the Anti-Submarine Warfare chief. As always, this was the most obviously busy place in the giant carrier. Always in half-light, illuminated mainly by the amber-colored screens of the computers, it existed in a strange, murmuring nether-world of its own, peopled by intense young technicians glued to the screens as the radar systems swept the oceans and skies.

Jack Baldridge was a stocky, irascible Kansan, from the Great Plains of the Midwest, a little town called Burdett, up in Pawnee County, forty miles northeast of Dodge City. Jack was from an old U.S. Navy family, which sent its sons to sea to fight, but somehow lured them back to the old cattle ranch in the end. Jack’s father had commanded a destroyer in the North Atlantic in World War II, his younger brother Bill was a lieutenant commander stationed outside Washington with the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence; somewhat mysteriously, Jack thought, but young Bill was an acknowledged expert on nuclear weapons, their safety, their storage and deployment.

Most people expected that the forty-year-old Jack would become a rear admiral. Naval warfare was his life, and he was the outstanding commander in the entire Battle Group, shouldering significant responsibility as the Group Admiral’s right-hand man. His kid brother Bill, however, who looked like a cowboy, rode a horse like a cowboy, and was apt to drive Navy staff cars like a cowboy, had gone as far as he was going. He was not a natural commander, but his scientific achievements in the field of nuclear physics and weaponry were so impressive the Navy Chiefs had felt obliged to award him with senior rank. Bill was a natural crisis man, a cool thoughtful Naval scientist, who often came up with solutions no one had previously considered. There were several elderly admirals who did not care for him because of his unorthodox methods, but Bill Baldridge had many supporters.

Where Jack was a solidly married, down-to-earth Navy captain of the highest possible quality, no one quite knew where Bill would end up, except in a variety of different beds all over Washington. At thirty-six he showed no signs of giving up his bachelor lifestyle and the trail of romantic havoc he had left from Dodge City to Arlington, Virginia. Jack regarded his brother with immense benevolence.

Down in electronic operations, Captain Baldridge was moving on several fronts. Captain Rheinegen, in overall command of the ship, had just ordered a minor change of course as they steamed over the Ninety East Ridge which runs north-south, east of the mid-Indian basin. Here the ocean is only about a mile deep, but as the carrier pushed on along its northwesterly course the depth fell away to almost four miles below the keel. Captain Baldridge had already calculated that the Tomcat probably hit the ridge as it sank and settled about five thousand feet below the surface.

He verified the positions of all the ships in the group, agreed with his ASW that four underwater “contacts” were spurious; he talked briefly to the Sonar Controller and the Link Operators; checking in with the Surface Picture Compiler. He could hear the Missile/Gun Director in conference with the Surface Detector, and he took a call on a coded line from Captain Art Barry, the New Yorker who commanded the eleven-thousand-ton guided missile cruiser Arkansas, which was currently steaming about eight miles off their starboard bow. The message was cryptic: “Kansas City Royals 2 Yankees 8. Five bucks. Art.”

“Sonofagun,” said Baldridge. “Guess he thinks that’s cute. We’ve just dropped a $35 million aircraft on the floor of this godforsaken ocean, and he’s getting the baseball results on the satellite.” Of course it would have been an entirely different matter if the message had been Royals 8 Yankees 2. “Beautiful guy, Art. Gets his priorities straight.”

Baldridge glanced at his watch, and began to write in his notebook without thinking, not for the official record, just the result of a lifetime in the U.S. Navy. He wrote the date and time in Naval fashion—“221700APR02” (the day, the time, 5 P.M., then month and year). Then he wrote the ship’s position—mid-Indian Ocean, 9S (nine degrees latitude South), 91E (ninety-one degrees longitude East). Then, “Bitch of a day. Royals 2 Yankees 8. Tomcat lost. Billy-Ray and Freddie hurt, but safe.” He, too, had a soft spot for Billy-Ray Howell.

221700APR02. 41 30N, 29E.

Course 180. Speed 4.

“Possible on 030, ten miles. Come and look, Ben. Maybe okay?”

“Thank you…yes…plot him, Georgy. He’s a coal-burner, and probably slow enough. If he keeps going for the hole, and his speed suits our timetable, we’ll take him. Get in…but well behind him, Georgy.”

“Take two hours.”

221852.

“They start to look for us. Time expired one hour. First submarine accident signal just in, Ben.”

“Good. What have you told the chaps?”

“What we agree. Cover for special covert exercise. We answer nothing. Soon they stop. We not exist anymore.”

“Okay. It’ll be dark inside an hour. Now let’s get organized for the transit. Watch for the light on Rumineleferi Fortress up there on the northwest headland, then go right in…follow the target as close as you possibly can.”

“Fine. Even though no one ever done it, right? Eh, Ben?”

“My Teacher once told me it could be done.”

“Ben, I do not speak your language, and my English not asgood as yours. But I know this is fucking tricky. Very bad cross-currents in there. Shoals on the right bank, in the narrows near the big bridge. Shit! What if we hit and get stuck. We never get out of jail.”

“If, Georgy, you do precisely as we discussed, we will not hit anything.”

“But you still say we go right through the middle of port at nine knots with fucking big white wake behind us. They see it, Ben. They can’t fucking miss it.”

“Do I have to tell you again? They will not see it, if you keep really close, right in the middle of the Greek’s wake. He won’t want to run aground any more than you do. He won’t push his luck in the shallow spots. Let’s go, Georgy.”

“I still not like it much.”

“I am not telling you to like it. DO IT!”

“Remember it is your fault if this goes wrong.”

“If it goes wrong, that won’t matter.”

222004.

“I want to be in our spot early, and get settled before we reach the entrance. We want a good visual night ranging mark on him. His overtaking light will do fine.”

“Slack Greek prick, leave them on all day.”

“I noticed. Use height ten meters on stern light.”

“What about his radar, Ben?”

“He won’t see us in his ground wave, and if he does, he’ll think it’s his own wake. This chap is no Gorschkov. He can’t even remember to turn his lights off.”

“What about other ships in channel?”

“Anyone overtaking will stay well to one side. Oncoming ships will keep to the other. My only real worry is the cross-ferries. That’s why we want to be going through the narrowest bits between 0200 and 0500, when I hope not to meet any of them. Bloody dreary if one of them slipped across our Greek leader’s bum and we rammed him.”

“How come, Ben, you know much more about everything than I do?”

“Mainly because I cannot afford mistakes. Also because I had a brilliant Teacher…bright, impatient, clever, arrogant…Stay calm, Georgy. And do as I say. It’s dark enough now. Let’s range his light, and close right in.”

281400APR02. 9S, 74E.

Course 010. Speed 12.

Eight miles off Diego Garcia the weather had worsened, the warm wind, rising and falling, making life endlessly difficult for the aviators. On the flight deck of the U.S. carrier Thomas Jefferson the LSO’s were in their usual huddle, taking advantage of the comparative quiet, talking to the pilots of the seven incoming flights from the day’s combat air patrol, four of them circling in a stack at eight thousand feet, twenty miles out.

The day-long exercises had demanded supersonic speed tests, and many landings and takeoffs. There had already been two burst tires, one of which had caused an incoming F/A-18 Hornet strike-fighter to slew left on the wire, and damn near hit a parked A-6E Intruder bomber.

Gas was now low all around. Tensions were fairly high. And before the six fighters came in, the entire flight deck staff was preparing to bring down the quarterback, Hawkeye, the much bigger radar early warning and control aircraft, unmistakable because of its great electronic dome set above the fuselage.

Jim Adams was calling the shots. Earphones on, yellow jacket visible for miles, he was racing through his mental checklist, yelling down the phone to the team below on the hydraulics. “Stand by for Hawkeye, two minutes.” He knew the hydraulic system was set properly, and now his eyes were sweeping the deck for even the smallest speck of litter. No one gets a second chance out here. One particle of rubbish sucked into a jet engine can blow it out. The whiplash from a broken arrester wire could kill a dozen people and send an aircraft straight over the bow.

Jim looked up, downwind. The Hawkeye was screaming in, the arresting wires spread-eagled on the deck, ready for the grab of the hook. Down below the giant hydraulic piston was in position, set to withstand, and stop, a seventy-five-thousand-pound aircraft in a controlled collision of plane and deck.

“Groove!!” bellowed Jim down to the hydraulic crew. This was the code word for “she’s close, stand by.”

Seconds pass. “Short!”—the key command, everyone away from the machinery.

And now, as Hawkeye thundered in toward the stern, Jim Adams bellowed:“Ramp!”

Every eye on the deck was steeled on the hook stretched out behind. Speech was inconceivable above the howl of the engines. The blast from the jets made the sky shimmer. At 160 knots the wheels slammed down onto the landing surface, and, right behind them, the hook grabbed, the cable rising starkly from the deck in a geometric V. One second later the Hawkeye stopped a few yards from the end of the flight deck, the sound of her engines dying quickly away.

Suddenly there was pandemonium, as the deck crews raced out to haul the Hawkeye into its parking place. Jim Adams shouted into the phone to change the settings on the hydraulics, the LSO’s were getting into position, one of them talking to the first Tomcat pilot, very carefully: “Okay one-zero-six, come on in—winds gusting at thirty-five, check your approach line, looks fine from here…flaps down…hook down…gotcha…you’re all set.”

Lieutenant William R. Howell was back in the game, with a new RIO, and a big plaster over his eyebrow. His pal Jim Adams was double-checking everything, as always. One by one he shouted his commands: “Groove…Short…Ramp!”—until Billy-Ray was down, to universal shouts of “Good job!” “Let’s go, Billy-Ray!” It was always a little tense on the first landing for a crashed aviator. Up in the control tower, Freddie Larsen was permitted to stand and watch, and if his arm had not hurt so badly he too would have clapped when Billy-Ray hit the deck safely. “That’s my guy,” he yelled without thinking. “Okay, Billy-Ray!” Even the Thomas Jefferson’s commanding officer, Captain Rheinegen, himself a former aviator like all carrier commanders, allowed himself a cautious grin.

And now, with a night exercise coming up, there was a change of deck crew. The launch men were moving into position, and aircraft were moving up from the hangars below on the huge elevators. All around, there were young officers checking over the fighter bombers, pilots climbing aboard, another group of engines screaming; uniformed men, many on their first tours of duty, were on their stations. The first of the Hornets was ready for takeoff. The red light on the island signaled “Four minutes to launch.”

Two minutes later the light blinked to amber. A crewman, crouching next to the fighter’s nose wheels, signaled the aircraft forward, and locked on the catapult wire.

The light turned green. Lieutenant Skip Martin, the “shooter,” pointed his right hand at the pilot, raised his left hand, and extended two fingers…“Go to full power.” Then palm out…“Hit the afterburners…” The pilot saluted formally and leaned forward, tensing for the impact of the catapult shot.

The shooter, his eyes glued on the cockpit, saluted, bending his knees and touching two fingers of his left hand onto the deck. Skip Martin gestured: “Forward.” A crewman, kneeling in the catwalk narrowly to the left of the big fighter jet, hit the button on catapult three, and ducked as the outrageous hydraulic mechanism hurled the Hornet on its way, screaming down the deck, its engines roaring flat out, leaving an atomic blast of air in its wake. Everyone watched, even veterans almost holding their breath, as the aircraft rocketed off the carrier and out over the water, climbing away to port. “Tower to Hornet one-six-zero, nice job there…course 054, speed 400, go to 8,000.”

“Hornet one-six-zero, roger that.”

281835APR02. 35N, 21E.

Course 270. Speed 5.

“Ben, we got rattle. Up for’ard.”

“Damn! We’ll have to stop, right away, fix it. We can’t afford to travel one more mile with that.”

“No problem. I will fix. Soon as it’s dark. Very quiet here anyway.”

290523APR02.

“At least the rattle’s gone. But I really am very sad about your man. It sounds heartless. I don’t mean it to be so. But I just hope they never find his body.”

“No time look anymore. Not blame anyone. Just freak wave. I seen it before. Now we say good Catholic prayer for him.”

“I should like to join you in that.”

041900MAY02. 7S, 72E.

Course 270. Speed 10.

Inside the mess room of the Thomas Jefferson, still off Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, big Jim Adams was giving a party in one of the ward rooms. Four hours earlier he had received a message that his wife Carole had given birth to their first son—a nine-pound boy, whose name would be Carl Theodore Adams. This, Jim explained, had been agreed two years ago, the first name for the longtime Red Sox outfielder Carl Yastrzemski, the second for the legendary Red Sox hitter Ted Williams.

And now little Carl Theodore had come in to land, and the aviators on the carrier were exercising two of their other major skills—making their two cans of beer (permitted on the sixtieth day out) last for about four hours, and feeling truly sorry for other human beings on Planet Earth who were not involved in the flying of jet fighter planes off the decks of the biggest aircraft carriers in the world.

A visiting commanding officer from one of the destroyers, Captain Roger Peterson, trying to dine in peace in a far corner with Captain Rheinegen, remarked to him that it takes a crew of more than three thousand men to keep the boisterous, white-scarved, winged heroes in the air.

No one heard, and it would scarcely have mattered if they had. Because the one shining fact known to any aviator is that all other forms of life, including submariners (especially submariners), guided missile experts, gunnery officers, navigation and strategic advanced warfare staff, were, and would ever be, their absolute inferiors.

Meanwhile Big Jim was up on his feet sipping his second can of iced beer, the last of his ration, making a little speech, in which he announced that Lieutenant Howell was to be Carl Theodore’s godfather. This provoked yells of derision, that Billy-Ray was a godless hillbilly and poor little Carl Theodore would receive no moral guidance in his whole life.

Billy-Ray stood up and told them that in his opinion such criticism was essentially “bullshit,” since his dad was a churchgoing Methodist back home in Hamlin, and that he considered himself an ideal choice.

This caused Big Jim to stand up and admit that Billy-Ray was only his second choice, but that since Yaz himself had not made himself available he was happy to move the selection process from an outfielder to a hillbilly. Anyway, he had instructed Carole to give birth while he was at sea because that would allow him to be first man off the ship when the Thomas Jefferson finally returned home in September.

041500MAY02. 36N, 3W.

Course 270. Speed 5.

“Okay, Ben, here’s island now. Can’t see much, on red 40, visibility not good.”

“Anyone live there?”

“Don’t know. Maybe few Spanish fishermen, but empty. Maybe your Teacher say city size of Moscow there but no one notice.”

“No. He told me it was empty too.”

“Anyway, you have plan for straits?”

“I have no requirements whatsoever, except we do not get caught. You’ve driven through here many times I’m sure.”

“Yes, but long time back—and Americans have better surveillance now. They got suspicion last time. Maybe satellite photo. Now how you make another miracle, Ben? How we go through in secret?”

“Basically, Georgy, old man, we have only one choice. Very slowly, very quietly, and hope to God no one really sees us.”

“No problem with that. I agree. You expect message from boss?”

“Not yet. Not until the final phase. Possibly not till the fuel turns up. Possibly not at all.”

“Okay. I make crew accept story. But this is long journey.”

“They’ll be well rewarded in the end. From here on, we must take extra care again. We’ll stay in silent drive at five knots for forty-eight hours. Ultra quiet, please, Georgy.”

061200MAY02. Fort Meade, Maryland.

Vice Admiral Arnold Morgan, Director of the National Security Agency, a short, hard-eyed Texan with grimly trimmed white hair, sat alone behind his desk. He was normally on three telephones, growling orders which would be relayed by satellite to his agencies throughout the world. The admiral’s reputation was that of a voracious and dangerous spider at the center of a vast electronic web of Navy intelligence resources. Most of the time he just watched. But when Admiral Morgan spoke, men jumped, on four continents and the oceans surrounding them.

Right now the admiral was curious. Open wide on his desk was the weighty current edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships, the British bible of the world’s warships. He had not expected it to provide an answer, nor did it. Neither did three other highly classified Naval reference books which were also piled around his desk.

Late on the previous evening he had received a satellite message. It had not been urgent, or alarming, or even particularly informative. It was, nonetheless, distinctly unsatisfactory, and something about it irritated Arnold Morgan. The story was simple: “Gibraltar facility picked up very short transient contact on very quiet vessel at 050438MAY02. Insufficient hard copy data for firm classification—aural, compressed cavitation, one shaft, five blades, probably non-nuclear. No information on friendly transits relate.”

Admiral Morgan understood that someone with very sharp ears on the other side of the Atlantic had heard a noise in the water, for a matter of twenty to thirty seconds, which sounded a lot like a non-nuclear-powered submarine. It was propelling on a single shaft with a five-bladed screw. It was probably well off-shore, almost certainly below the surface, and had made the noise either by speeding up somewhat carelessly, or putting her screw too shallow for the revolutions set. Perhaps she had momentarily lost trim, pondered the admiral, himself an ex-submariner, ex–nuclear commander.

In the good old days it was possible to discern a Soviet-built boat because of their insistence on six-bladed props when Western nations went for odd numbers of blades, three, five, or seven. If Admiral Morgan closed his eyes tightly, and cast his thoughts back twenty-three years to his own days in the sonar room of a Boomer, deep in his mind he could hear again the distinctive “swish—swish—swish—swish—swish—swish” of the blades on a distant old Soviet Navy submarine.

They used to be hard to miss but it was much more difficult nowadays to identify any submarine. Even modern, quiet fishing trawlers can make this kind of noise if they speed up suddenly and inadvertently hassle the haddock. But Admiral Morgan had no interest in fishermen. The only furtive, five-bladed fucker he would worry about was a submarine. And he could sort that out pretty quickly.

Admiral Morgan was a living, snarling encyclopedia when it came to checking out foreign warships. He wanted to know what kind of contact it was, who the hell was driving it, and where the hell was it going. The merest possibility of a submarine had that effect on him.

It took about five minutes on the computer for the admiral to figure out that it could not have been an American or British boat. A bit longer to find out that it could not have been French or Spanish either.

Israel had one submarine of Russian origin in service that he knew of, but there was a record of it entering the Atlantic four weeks ago. So it was not them. The goddamned Iranians had three they bought from Russia, but they had all been accounted for in the Gulf recently—thoroughly enough for him to know that none of them were that far from home.

He knew the Indonesians had some old and defunct Russian boats, which were unlikely to have cleared the breakwater in safety. Even the Algerians had a couple of Kilos, brand new in 1995, but both were back in refit, he knew, in St. Petersburg. The Poles had one in the Baltic, the Rumanians one in the Black Sea, both out of action and both recently observed. The Libyan’s Kilo fared no better than its six “Foxtrot” predecessors, two of which sank alongside—it had not been to sea for a year. The Chinese had quite a few, more modern designs. But none of these people had any known business in the strait.

He had already played a long shot and placed a call to his opposite number in the Russian Navy in Moscow. It was all very cheerful these days, and without hesitation, the Russians told him they had not sent any of their diesel boats through the strait for eighteen months.

In fact the only Russian diesel unaccounted for was lost in an accident in the Black Sea about three weeks ago, and was right now resting in seven hundred meters of water with everyone in it dead. They were still searching, but had found her special indicator buoys drifting, and a small amount of debris.

All of which baffled Admiral Morgan. He kept repeating to himself the same scenario. If one of the U.S. Navy’s sonar wizards said he had heard a quiet propeller, then the admiral believed there had to be a suspicion in that operator’s mind.

Only a few people can even hear these subtle, distant sound waves, and even fewer can recognize them. And if his man in Gibraltar said he had heard one shaft and five blades, then that was what he had heard. But this guy had not only bothered to report it, he had also included a veiled personal suspicion that it was “probably non-nuclear.”

“I think our man suspects it was underwater,” Morgan thought. “The contact was transient. And the trouble with all transients is their similarity to code-breaking…if you have just a small sample you don’t really know much. Just enough to want to know a bit more. Like what precisely was the type of boat, and who was driving the bastard?

“But our new friends in Moscow are saying no—and why should they lie? Not only are we at peace, we could not give a rat’s ass if they drove a diesel up and down the Atlantic all year, calling at all stations. If they pitched up in Norfolk, Virginia, hell we’d probably give ’em a cup of coffee.”

When he had first seen the message, he did not understand. And he still didn’t. The facts seemed mutually exclusive—a mental outcome guaranteed to infuriate him.

At fifty-seven, Arnold Morgan was a driven man, a ruthless demander of matching, orderly facts. Admiral Morgan did not accept Chaos Theory. This character trait had cost him two marriages, and strained his relationships with his children. The Navy regarded him as the best intelligence chief they’d ever had. If there was one single criticism of him, it was simply that he was inclined to become over involved in what some people considered petty details.

“I do not accept incompatible facts,” he said firmly to the still-empty room. “That, gentlemen, is a matter of principle.” And with that, he consigned the signal and all of the results of his many questions about the phantom contact to his highly efficient electronic filing system. His only comfort lay in the knowledge that if indeed it was a submarine, it would turn up somewhere, sometime, and the problem would be resolved.

Until then, he decided to put it down as a kind of fishy snafu. And the admiral detested all snafus. Especially underwater snafus, because those were, unfailingly, both expensive and embarrassing.

“So perhaps it was,” he announced to the empty room, “just a fishing trawler. Perhaps our man was just a tiny bit overzealous. Hmmmm.”

Then, visibly brightening, “Unless some bastard’s lying.”