0730 Friday, August 9.

BILL BALDRIDGE DEEPLY REGRETTED HAVING STAYED out half the night in Istanbul with the CIA man from Washington. He leaned over the rail of the northbound ship and wished, fervently, that he had never laid eyes on a bottle of raki. His head throbbed, he felt repulsively ill, and there was a mild tremble deep within his body. He had been leaning on the rail for almost two hours, and the gentle rhythm of the teal-blue waters of the Black Sea was causing his condition to worsen.

There were two questions banging around in his aching mind: What was he going to find in Sevastopol to prove Benjamin Adnam had been there? And, was Benjamin Adnam really an Iraqi who had been working for years, undercover, in the Israeli Navy?

They were big questions. And he wished he felt better able to cope with them. Ted Lynch was still waiting for a report from the Mossad on the wire-tapped Geneva conversation. But by now Bill felt certain there must be some evidence in the Russian submarine port to suggest that someone, somehow, had been paid a huge amount of money.

He hoped Admiral Rankov would be cooperative. And he hoped he would get into Russia as easily as Admiral Morgan had predicted. Twenty-four hours later, very early on the still-dark Saturday morning of August 10, his faith in Arnold Morgan was confirmed. He was met by a young Russian Navy officer, Lieutenant Yuri Sapronov, who spoke excellent English and marched him through Odessa’s dimly lit customs and immigration rooms without missing a beat. He carried the American’s suitcase, but not the briefcase, which contained the phone scrambler, and he explained they were immediately boarding a Navy vessel which would run them across the water to Sevastopol in under six hours. They would arrive by 1300.

The ship turned out to be Russia’s fastest attack patrol craft, a Babochka Type 1141, with an anti-submarine capability. Lieutenant Sapronov said the boat was capable of forty-five knots and was making the crossing from Odessa to its home port of Sevastopol. Admiral Rankov had personally instructed Sapronov to pick up Lieutenant Commander Baldridge.

Recovered from the excesses of Thursday night, Bill enjoyed the journey, chatting for much of the way with the young lieutenant, who turned out to be a native of the Crimean coast, from the easterly dockyard city of Feodosiya, where the Babochka was originally built.

“Everyone here worried about the missing Kilo,” Lieutenant Sapronov had admitted. “Admiral Rankov has been yelling and bellowing about it for two weeks. And he’s a very big guy to yell that loud. He’s my boss. I’m his Flag Lieutenant. At the moment we are in just a temporary office, thin walls. The whole fucking place shakes whenever anyone even mentions that Kilo. He can’t understand how a submarine can just disappear. Tell you the truth, neither can I.

“Each day I look after his signals and letters back to Moscow. He’s very concerned that Americans think we are lying. Last week he sent a long communiqué to Moscow to Admiral Zubko—he’s the C-in-C, and Deputy Minister of Defense. He said Americans suspicious the Kilo had something to do with that aircraft carrier which blew up in the Gulf. He said it was essential we help Americans all we can. Zubko faxed back right away he agreed with everything. I guess that’s why you’re here.”

Bill reckoned that was all a bit too fluent not to have been rehearsed. But Admiral Morgan had said he could trust Rankov and he was certain the Russians were ready to help any way they could. “Sure is a mystery,” he told the lieutenant. “Have you guys been following up on the families of the crew?”

“Oh, sure we have. We’ve had people visiting them, even watching some of their homes. Guys from the old KGB. But no one has found a sign of anything. No money around, no one looks as if they have been bribed. Everything seems desperately sad but essentially normal. Admiral Rankov gets crosser every day. I heard him yelling down the phone to someone yesterday.”

At this point Lieutenant Sapronov did a deep imitation of a fairytale giant’s voice, and continued: “‘There’s nothing fucking normal about this. Nothing!! Do you hear me?’ I guess the guy on the other end nearly had a heart attack. But we still didn’t get anything new.”

Bill laughed. He liked Russians, as almost everyone does who meets them. They are usually very frank and open, with a good sense of fun, and an unfailing irreverence about authority, once they get loosened up. He and the lieutenant enjoyed a good breakfast of kolbasa, the smoked sausage native to the Ukraine, with scrambled eggs, toasted lavash bread, and Russian coffee, which Bill thought was not a whole lot different from that at Chock Full o’Nuts.

Afterward they sat on deck in the morning sun, sipped vody Lagidze, the cold Russian mineral water mixed with various syrups, and watched the fast-approaching coastline of the Crimean Peninsula. Right after 1230, the Babochka cut its engines for the run into the short bay of Sevastopol, and Bill was on the jetty before 1300. Admiral Vitaly Rankov was there to greet him. The towering exSoviet international oarsman, whose eyes were as gray as the Baltic Sea, and whose handshake resembled that of a mechanical digger, was an imposing figure.

“Welcome, Lieutenant Commander,” he rumbled in a deep bass voice, which Bill thought would probably have done justice to the role of Sparafucile in Rigoletto. “I know you are one of Admiral Morgan’s staff. I know Arnold well, and I do not envy you. He is a terrible man!” Admiral Rankov joked as they walked along the dockside. They came to a group of newly built offices that resembled those on a New York construction site. Admiral Rankov and his staff occupied about six of the wooden structures during the weeks he was working with the High Command of the Black Sea Fleet. Every step he took in his office made the place shudder, every door he closed threatened to bring down the ceiling. Bill thought the floor might give way altogether when he banged his huge fist on the desk for emphasis. This was a man, he thought, who belonged in the vast, vaulted stone halls of the Kremlin, where Admiral Morgan felt he would most assuredly end up.

“Right, Lieutenant Commander,” he said, once he had attended to his more urgent messages. “I instructed Yuri to give you a little background on our progress, but if there is anything you particularly want to know, please feel free to ask me. By the way, we still have no hard evidence about the fate of the Kilo.”

“Well, sir,” said Bill, “I think the main purpose of my visit is to try and discover whether any suspicious-looking character from the Middle East was seen around here at all. You see, we think someone bribed your captain with a huge sum of money. Someone must have seen him.”

“Yes,” replied Rankov. “Arnold Morgan told me what you have worked out, and I’m just beginning to think you may be right. What other explanation can there be? We can’t find the wreck. The drowned sailor who was a member of that ship’s company? Found off the coast of Greece? The Kilo must have got out. But it’s still very difficult for us to find out how. This place is crawling with people from the Middle East. The Iranians have a fucking office here!”

“How about the Iraqis?”

“No office. But they’re not strangers. They want to buy two or three Kilos, but right now they have no money to spare, and we’re giving no credit to anyone, however good their credit might be. Right now it’s—how you say it?—cash on the drum.”

“Barrel,” said Bill.

“Right. Cash on the barrel. The Iraqis have been arms customers of ours for a long time, as you know. But if they can’t pay, we can’t supply. Things here are very bad financially. And we just don’t have the backup to go around giving away submarines for which we might get paid, sometime. Also you Americans have things wrapped up pretty tight now. We’d rather be your friends, and we don’t much want to do anything which will endanger that friendship.”

“No submarines for a mad dog like Iraq?”

“Lieutenant Commander, I have to be straight. If anyone comes in here waving a billion dollars for submarines, we will supply. We don’t care if they’re Chinese, Arabs, Persians, or even Eskimos.”

“We have noticed that,” said Bill, grimly.

“You don’t know what it’s like to have your backs to the wall over money,” said Rankov. “For a big nation like ours, it’s a dreadful thing. And it’s been happening here for almost the whole of the twentieth century. And it’s still happening now we’re in the twenty-first.”

“Yes, I suppose so. But would you have noticed a stranger who looked like he came from an Arab nation hanging around here at the time, early April?”

“Well, I certainly would not, because I was not here at the time. But I do not think anyone else would either. There are just too many people who would fit that description. Anyway, I do not think your man would just have been hanging around. He could not have got in through the gates, not without being brought in by a Russian official or at least a serving officer.

“Quite honestly, I’m inclined to agree with Arnold Morgan. I think his rendezvous was arranged. And he bought the captain with a massive amount of money, and then that captain fooled the crew into going on a secret exercise on behalf of the Russian Navy. Nothing else fits.”

“Who was the captain?”

“A very well-respected Russian officer. A native Ukrainian, as so many of our submarine commanders are. Captain Georgy Kokoshin. He’s very experienced without being brilliant. Man of about forty-two. Married to a much younger woman, Natalya. They have two young children, six and eight, both boys. The family lives on the edge of the city in one of those new high-rises. We’ve been checking there on and off for over three months now. Ever since the submarine was reported lost. But everything seems normal. Mrs. Kokoshin was very, very upset over the death of her husband.”

“When did you last check?”

“I believe I had a report in on Tuesday morning. The children were at school as usual.”

“No new cars, new clothes, nothing extravagant?”

“Nothing.”

“Did you search their apartment? Ransack it from top to bottom?”

“No. We did not. Captain Kokoshin was a senior Russian commanding officer, presumed dead. He was very popular, and no one wanted to treat his widow as a criminal. In some respects we are in a similar position to yourselves. You do not wish to admit your carrier was hit by an enemy. We do not wish to admit we have mislaid a submarine and its crew. If we start harassing the wives of the officers, word will get around that something is wrong.”

“Yes. I guess so. Have you done any checks at all on any of the families of the other senior officers?”

“All of them. We found nothing.”

“And the Kilo sent no signal whatsoever once she had cleared the port of Sevastopol?”

“Nothing.”

“Well, would you mind if I have a look around? Could you just show me the area where the submarine was moored, let me see where the captain and some of his officers lived? I have to make a report about this visit to Admiral Morgan.”

“Certainly. I will show you what you wish to see, as I promised Arnold Morgan.”

It was a short walk to the submarine area. When they arrived Lieutenant Sapronov was awaiting them, standing in front of a Kilo, identical, Bill supposed, to the one he believed had hit the Jefferson.

“This is where she lived, Hull 630. This is where she was last seen. This is where she sailed from, at first light, on the morning of April 12.” Admiral Rankov spoke as a man who has gone over the ground many times.

Before him Bill could see another slightly shabby, black-painted submarine, similar in size to Unseen, which he had visited four days previously. The Kilo looked a bit basic compared to some of the modern American designs, but he knew she ran deathly quiet beneath the surface, probably quieter than the U.S. boats, and he knew that her torpedoes were both accurate and lethal.

He stared up at three of her masts, jutting out from her long, slim sail. And he imagined in his mind, the dull, familiar clunk of the big SAET-60 exiting the tube, the whine of the engine as the underwater missile raced straight toward its target, its nuclear clock ticking, its warhead primed to explode and incinerate. The ice-cold eyes of Ben Adnam somewhere beneath the periscope.

Bill shuddered. He gazed around at the uniformed Russian Navy personnel walking by. There were a lot of people around the submarines. In just the few moments he had been here, four different crew members had left the Kilo, two of them officers. He assessed that it would have been impossible for an Arab hit-squad to have penetrated this dockyard and commandeered the submarine.

No. Someone bought Captain Kokoshin. And that someone was Benjamin Adnam. He had the brains, the backup, the know-how as a submarine commander himself, and the cash. He also had the arrogance. Jesus, Bill thought, the guy even traveled here the first time under his own name, despite being on the run from the Mossad as a deserter from the Israeli Navy. He was a cool customer, no doubt about that.

“You want to go aboard?” asked Admiral Rankov.

“Can I see the weapons area, the tubes and the warheads?”

“No. I’m afraid you can’t inspect that area. No one can, except for the captain, the weapons officer, and his staff.”

“I am a weapons officer,” said Bill, smiling.

“Wrong Navy!” laughed Rankov.

Bill laughed with him, and then made his first formal request. “Can we go and have a talk with Mrs. Kokoshin?”

“We can, certainly. But I’d rather do it in the morning. I have some people to see this afternoon. And I had thought I would have someone take you to your hotel. You can get yourself unpacked and have some coffee. Then I will meet you at around 1900 for dinner. I stay at the same hotel when I’m here.”

“Sounds pretty good to me,” said Bill. “Okay, I’ll take off. I’ll call Admiral Morgan from the hotel, and meet you later.”

The two officers shook hands. And Lieutenant Sapronov led Bill to a black Mercedes limousine parked right off the jetty. The engine was already running, and the lieutenant issued an instruction to the driver, who jumped out and opened the rear door for the American. They drove out slowly, pausing at the security building adjacent to the dockyard gates. Bill counted at least eight armed guards in proximity, and he again thought it impossible for an armed squad of men to penetrate this place. So much more efficient to “rent” your submarine.

The Mercedes rolled through the gray, run-down streets. There were few people to be seen, and cars were rare. The surface of the road was appalling by Western standards. The omens of decay were everywhere. The woeful streets, with their high apartment houses, all around the outer dockyard area of Sevastopol, made Barrow-in-Furness look like Fifth Avenue.

Beyond the inner city, Bill thought the place looked a bit more cheerful. But Sevastopol, steel-ringed by the Soviet Navy for generations, was not long on hotels. This was one of the last areas in all of the Ukraine to acquire a hotel built by a foreign corporation. As late as 1995 there was no such establishment in the entire state, not even in Kiev.

But, by the turn of the century, one of the enterprising Finnish hotel groups was on the move. They had constructed a new hotel on the outskirts of the city which had housed the Soviet Black Sea Fleet. It was called the Krasnaya, and it existed for the scores of visiting foreign executives who had journeyed to Sevastopol to buy exSoviet warships, and in some instances, new ones. Kilos.

The place was full of non-nationals, from the Middle East, East Asia, South America, and all kinds of Third World republics, who were either trying to buy warships to frighten their neighbors, or to protect shipments of drugs. Some of the better-heeled patrons, from the Gulf states, had matters more sinister on their minds. It was a perfect place for the huge, apparently genial Russian Naval Intelligence officer Rankov to stay. And Bill Baldridge summed that little scenario up in short order, before he even registered.

Up in his room he prepared to call Arnold Morgan. He took the portable phone scrambler from the depths of his suitcase, placed it on the bed, and opened the lid. He then put the hotel phone handset into a special cradle in the case, and set up the electronic crypto system, which would render their conversation unintelligible to an outsider. Then he made the call on the regular open line. When the admiral answered they would go over to encrypted mode simultaneously. The process was tricky, but very effective.

“Morgan…speak.”

“Baldridge…preparing to speak. Stand by crypto August 10.”

“Roger, standing by.”

“Crypto three, two, one. Go. How’s that, Admiral?”

“Terrible, Bill. But I can hear enough.”

Arnold Morgan explained that he had been in touch with Major Lynch, and that the spotlight of suspicion, which had shone for so long on Iran, was now shifted to Iraq.

The Mossad had given orders to tap into the telephone system in the lakeside mansion of Barzan al-Tikriti, one of Saddam Hussein’s half-brothers, and Iraq’s Ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva.

The Mossad knew better than anyone how to follow money, particularly counterespionage money. Barzan was one of Iraq’s leading financiers. He had helped to mastermind the plan which enabled the Iraqi dictator to siphon off between 3 and 5 percent of every barrel of exported oil, and turn it into a multibillion-dollar hoard of cash and gold in Geneva.

The money had traveled efficiently from the Iraqi Treasury into an account called Patriotic Revolutionary Guard Number 473 in the Central Bank of Iraq. From there it was wired to a private bank in Vienna, where numbered accounts were still used. And from there into the account of a Swiss corporation in Geneva, administered by Barzan al-Tikriti. At the last count there was more than 2 billion dollars in that one account, and it was from there that Saddam Hussein broke every international law with regard to purchasing arms.

A relatively small matter, like withdrawing 10 million in cash in order to strike a secretive and massive blow at the “Satan of the West” was kid stuff to an operator like Saddam. Just as long as he had the right man for the job.

The Mossad’s agents had been very certain in their reports to General Gavron. The Iraqis would have trusted no bank, no broker, no wire transfer, in moving the money on its final step from Geneva to Istanbul. That was why Ted Lynch had drawn a complete blank in the Turkish banks.

The vast amount of cash required to “hire” a Russian submarine would have been crammed into a couple of hard, specially rimmed suitcases, and would have traveled on a direct flight, in the first-class luggage cupboard of a Swissair Boeing, under the watchful eye of Barzan’s highly paid personal assistant, a statuesque Austrian blonde named Ingrid Jaschke. She, in turn, was always accompanied by an Iraqi bodyguard, bagman, and professional assassin, who traveled behind her in a business-class seat, probably on a highly respectable Egyptian passport. Kamel Rasheed was the name he went by.

Ingrid never went anywhere without a small custom-made German pistol, which fired snub-nosed bullets designed to spread on impact, thus leaving a tiny entry hole, but a massive exit wound. She was fully licensed to carry the pistol, and she always checked it with the airline, and then collected it on landing. There are many really lousy ideas associated with international arms dealing. One of them would be to try and rob Ingrid Jaschke, anywhere beyond the airline arrival gate.

Right now four men from the Mossad were combing the main hotels in the mysterious city of Istanbul, utilizing charm, cash, and persuasion, to try and establish whether Miss Jaschke, and/or Mr. Rasheed, were in residence in the city between April 7 and April 13, 2002—these were the nights most likely to have seen the second arrival in the city of Commander Benjamin Adnam.

The admiral explained to Bill that this was not such a daunting task, since Miss Jaschke was not the kind of woman to shack up in a youth hostel. If she was in Istanbul that night, she would have been in one of the best hotels in the city. It is, after all, against no law to walk around with a couple of big cases full of cash. So long as you own both the cases and their contents.

The Mossad was also trying to check the airline, but Swissair was apt to be more secretive than even the Swiss banks. However, one Israeli agent thought he could get his hands on the passenger lists out of Istanbul to Switzerland in the first half of April. Safe behind the encrypted technology, Admiral Morgan explained all of this to his Kansas-born field officer.

“It beats me how those Israeli guys are so efficient,” Admiral Morgan finally growled down the telephone to Bill Baldridge. “I don’t know where they get their information half the time. But every time I talk to the embassy they have advanced the search further. Every time I talk to the CIA we have nothing more than the Mossad is telling us. And there’s twenty-five thousand people on the staff in Langley. Christ knows what they’re all doing.”

“I guess it’s because the Mossad is so damned small and tightly controlled,” said Bill. “What have they got, twelve hundred people—only thirty-five case officers? What are they called? Katsas?”

“Yeah. But there’s something more to it, Bill. Israel has a ton of people, all over the place, who are deeply sympathetic to its plight, and its fears. They are a kind of unseen army, numbered in their thousands in almost every country. They are always there to help any Mossad agent. The Israelis call them ‘the sayanim’—and they have vast computerized lists of ’em. That’s how they tap into real information.

“I guess that’s how they got into Barzan al-Tikriti’s phone line. A Swiss Jew involved in the telephone system in Geneva. A favor from a proud member of the sayanim, for his spiritual home in the Middle East. That’s how it works.”

“So right now they’re looking for a helpful Turkish Jew in the hotel business in Istanbul,” replied Baldridge. “A guy to see them on the right track, to call a couple of friends, check out those guest registers?”

“You got it, Billy. That’s how it’s done. Stay close to Rankov. He wants to find that Kilo too. And stay in touch. Call me if you get anything.”

The phone went dead. Bill was still holding the receiver, as always. “Oh, thank you very much,” he said sarcastically. “It was so nice to talk to you, Admiral Morgan. Have a nice day, rude asshole.”

Bill showered and changed, gazed out of the window at the soulless spread of Sevastopol. In the near distance he could see the giant cranes of the shipyards. He decided to wander downstairs, have some coffee, and then go to the bar to meet Admiral Rankov. The coffee was pretty nondescript, and he skimmed through a copy of an English-written Arab newspaper he found on the next seat.

There was a picture of the wrecked floating dock, jutting out of the water in the harbor of Bandar Abbas, but the caption carried no suggestion of anything more than an accident in the dockyard area.

Bill signed the check, and decided to play a mild hunch. He knew now that the Kilo had sailed on April 12, which he had not known before he talked to Rankov. And he felt instinctively that if Adnam had been in Sevastopol in the days leading up to that sailing, he had stayed in this hotel. Everyone in the shipping and arms business did. But, unlike the Mossad, he could not spend days trying to get into a Russian hotel guest list for the first part of April. They would never reveal anything. Not here.

But there was one thing he could do immediately, and he strolled outside to talk to the waiting limousine drivers who inhabit the fore-courts of hotels such as this.

The first man he spoke to wore a gray uniform. No, he had never had a long distance run to the southern border of Georgia and Turkey. But he thought Tomas did, back in the spring, and Tomas had just arrived back in the forecourt. Bill then sought out Tomas, a thick-set, blond young Russian. Aged around twenty-five. Yes, he did once have such a customer. Back in April. They drove all through the night, stopping only for gasoline. He remembered it well, because it nearly caused him to be divorced. “My wife was not at home so I could not tell her, and the man wanted to leave immediately. So I just went. Made it in fourteen hours—six hundred miles, right down the coast road, through Sochi. He was an Arab gentleman, paid me two and a half thousand American dollars, cash. Best job I ever had.”

“How come you nearly got divorced?”

“I forgot it was her birthday. We were going out to celebrate with friends. It was awful, I phone her from Batumi. She says she never speak to me again. Slammed down the phone. I drive all the way back not knowing if I’m still married. If I had not agreed to share the money with her, I would not be still married.”

“Do you recall the name of the man?”

“No, he never told me that. He hardly spoke.”

“Do you recall what he looked like?”

“Not really. He was an Arab. Dark-skinned, tight black hair. Not very tall, about my height. But well built, muscular.”

Bill reached into his pocket for his wallet, took out the grainy, fax machine photograph of Benjamin Adnam in Arab dress—the one they had taken in the Israeli search room at the Allenby Bridge. It was absolutely useless except to the eyes of someone who knew Adnam well. But Bill held out hope for the Russian driver.

“Could this have been him?” he said, handing the photograph to Tomas.

“Well, it could have been,” he replied. “But the man I took to the border was not wearing a headdress. I cannot really tell from this. It was night, and I hardly saw his face. He rode in the backseat. This photograph could be any one of fifty Arabs I have driven for. I could not say this was the man I drove to Georgia. But then, I probably wouldn’t recognize him if he was standing here right now.”

“Where did you leave him when you arrived in Georgia?” asked Bill.

“In the town. There was another car there to pick him up, and take him on. I think he was going to Turkey but I could not tell whether by road, or on the hydrofoil to Trabzon. I have never seen him since.”

“Thanks, Tomas,” said Bill, pressing a ten-dollar note into the driver’s hand. “By the way, when’s your wife’s birthday?”

“I never forget that again. April 11.”

The time was now 1858 and Bill Baldridge wished the driver good evening and walked back into the hotel to find the bar. He was mildly surprised to find the admiral already there. His Russian uniform cap was on the seat beside him, and the admiral was sipping a glass of gorilka z pertsem, vodka with a small red pepper floating in it. The vodka was a special Ukrainian variant, and Bill, wary of his last run-in with foreign liquor, settled for a scotch and club soda, which was not so elegant in flavor as that at Inveraray Court.

Admiral Rankov was enjoying his drink, taking steady gulps as they talked. Bill half-expected him to hurl the glass over his shoulder in some kind of crazed Cossack ceremony. But before he could, a bell captain came over to announce a phone call for the admiral.

When he returned, Vitaly Rankov’s big, handsome face was grave. “This is trouble,” he said. “I can sense it. That was young Sapronov. The KGB observers’ daily report says Mrs. Kokoshin’s children did not attend school today. And they were not there yesterday either. They want to know what to do. The school knows nothing, except they are absent.”

“I know what I’d do,” said Bill. “I’d get round to her apartment real quick. And I would not alert the entire secret police force of the Ukraine either.”

“You mean now?”

“Hell, yes. You got the address?”

“Sure I have.”

“Then let’s go. I might be able to help.”

“This is a bit irregular, conducting a search of a Russian officer’s premises in the company of an American Naval officer.”

“Do you want to be in partnership with the USA in the search for the boat?”

“I not only want to be, I am instructed by the Kremlin to work with you all the way.”

“Then let’s get the hell out of here and see what shakes with Mrs. Kokoshin.”

The admiral signed the check, and they headed out to the car. Rankov gave the new driver the address, and told him also to step on it.

The Kokoshin family lived only ten minutes away. Their apartment building stood about ten stories high. There were glass swing-doors, but no doorman on duty. The captain’s family lived on the eighth floor, number 824, and Bill stood aside while the admiral rang the bell twice. They could see there were lights on in the apartment, and they could hear a radio or a television in the background.

No one answered. Rankov hit the bell again, this time three rings. They waited but no one came. “Maybe she just went to see a neighbor,” said the admiral.

“Why don’t we check?” said Bill. They walked along to number 826 on the same side of the central corridor. The admiral rang the bell, and again there was no reply.

“Let’s have a shot at 822,” said Bill. And there they were more fortunate. The woman who answered the door did know Mrs. Kokoshin. She had not been home all day, nor was she home yesterday when her own children had come from school and tried to find the Kokoshin boys.

She suggested the admiral try the lady on the opposite side of the corridor, number 827, who was a good friend of Natalya Kokoshin and might even know where she was. “Sometimes she goes to see her mother, who lives about forty-five minutes from here—little place called Bachcisaraj.”

The bell didn’t work and they knocked on the door. Another Ukrainian housewife answered, and was unable to offer much help. “I have not seen her for two days, which is unusual,” she said. “She was late home the day before yesterday, because her boys called here for the key. She arrived at about five o’clock and returned the key. I haven’t seen her since.”

“Do you still have the key?” asked the admiral.

“Yes, I do, but I don’t think it would be right for you to borrow it.”

“I assure you it would,” boomed Rankov. “I was her husband’s boss, and my business is very urgent indeed.”

The neighbor fled from the wrath of the gigantic uniformed Intelligence officer, and returned with the key a moment later.

The admiral thanked her profusely, bowed low, and waited until she had closed her door. Then he walked quietly over to the home of Natalya Kokoshin and her children. The key turned easily. Rankov pushed open the door. The lights were on, and he could see the television turned on in the living room. The occupants were long gone.

The place was tidy. But hollow. There was nothing in any bedroom cupboard, the drawers were empty. It was obvious the clothes had been taken, along with shoes and coats. But all the furniture was in place and the kitchen was untouched. The windows were closed and locked. The Kokoshins, observed Bill, were history.

“Do we go back and grill the neighbor opposite?” asked Rankov.

“Hell, no,” replied Bill Baldridge. “That would be like taking out a half-page ad in the Ukraine Times, or whatever it is. Since we now know what has happened, I think we should turn off the television, close the drawers, put out the lights, return the key, and leave. Quietly.

“Then, if I were you, I’d get your KGB guys to check airports, border crossings, the shipping lines, and all the routine stuff we do when we are searching for missing persons.”

“You’re right. Let’s get back to the hotel. I’ll call Sapronov and put plan in action.”

“Not that it will do the slightest bit of good,” said the American.

“Why not?”

“Because I think that lady is carrying a suitcase full of dollars. And you can cover a lot of trails, a lot of rules, and a lot of miles, with that kind of cash to speed your way. She’s been gone for two days. She could be on the other side of the world by now. She’ll be hard to track down.”

“I wonder how she got out of Russia,” said Rankov.

“With that much cash she had a thousand options,” said Bill. “She could have hired a car and driver and headed for the border. She could have hired a boat and headed down the coast, but that’s probably too slow. She could have hired a small private plane, or even a helicopter, to get down to Georgia, and then cross into eastern Turkey. The cash makes almost anything possible, and if she has the same backup we think she has, documents are going to be no problem whatsoever.”

“How would you do it, Bill Baldridge?” asked Admiral Rankov, slipping into the Russian habit of using both names.

“I’d make for Georgia, as fast as I could get there, and enter Turkey at the border-crossing post at Sarp, or cross over on the hydrofoil which takes non-Georgian nationals from Batumi to Trabzon. It would depend on what documents I had for myself and the two boys.

“I’d guess Natalya has been stockpiling clothes and possessions at her mother’s house for several weeks, and paid a private driver, say, five thousand dollars, to take her through the night to Batumi. They probably walked out of their apartment emptyhanded at around six the previous evening. Nothing remotely suspicious about that. Then they hit the road. First stop, Mum’s house, second stop gas station, and on to the southern border.

“I think it’s about six hundred miles down the east coast, but if they averaged 40 mph and made one night gas stop on the way at around 2300, they’d do it in fifteen hours. That would have put them in Trabzon yesterday morning around 0900.”

“And then where, from Trabzon?”

“Oh, that’s easy. No hurry. There are direct flights from Trabzon to Istanbul, and she’s had four months to make sure she arrived at exactly the right time to catch one of ’em. Then she took the British Airways evening flight to London, and on to wherever the hell she’s headed. Probably South America. If I had to guess I’d say she was out of Turkey and on her way to London, or even Paris or Madrid, last night. And, remember, she’s broken no law. She’s just taken her children to live somewhere else. So what? The South Americans will never extradite her, even if you find her.”

“You Americans are so very accepting of human behavior,” said the admiral with a smile.

“That’s right. That’s why we’re rich, and you’re broke. Go with the flow, old buddy. Saves you a lot of time and trouble.”

“Well, I guess we’d better give back the key, and head back to the hotel. I do have to report all of this, of course.”

“Sure you do. And what’s more you must find her. Because where she is, is where Captain Georgy Kokoshin is headed, right now, with his crew.”

On Sunday morning, August 11, the U.S. lieutenant commander traveled with Admiral Rankov in a military aircraft as far as Kiev, for an overnight stop en route to London. He checked in to the Ukraine Hotel on Taras Schevchenko, and prepared to call Admiral Morgan at his home in Maryland. It was 0900 in Washington. Once more he unpacked his telephonic scrambler case and placed the hotel phone in the electronic cradle.

“Morgan…speak.”

“Baldridge…preparing to speak. Stand by crypto August 11.”

“Roger. Standing by.”

With the crypto locked on, and their conversation now protected from prying ears, Bill explained that the Kokoshin family had fled. He passed on Admiral Rankov’s kindest regards. “If you want him this week, he’s in his office in Moscow.”

Admiral Morgan confirmed it was looking more and more like Iraq, but he had not yet heard whether they had run Ingrid Jaschke to ground. He had spoken to Scott Dunsmore the previous night, and the CNO reported that the President was unflinching in his attitude to a global submarine hunt. “Get through the Bosporus underwater,” he had said. “Then I’ll authorize anything you want. But I’m not doing anything if you guys fail on the mission.”

Bill’s news was critical. And it fired up the American admiral. “Does Rankov want us to help find her?” he said. “He’s welcome to all of our resources.”

“He didn’t say so, sir. But I think he’s very worried about his own position. They just lost a submarine, which is about to embarrass the entire nation, and his guys have allowed their prime witness to slip through their fingers. Old Vitaly’s a bit depressed, to tell the truth.”

“Guess he would be. Hey, where are you? You on your way home? Or you going back to see MacLean?”

“Right now I’m in Kiev. Then I’m headed back to London, and I guess home. Unless you want me to stay in Europe.”

“I don’t think so, Bill. You need to be in Istanbul on September 6. But there’s no need to make the outward journey to Turkey in the boat. Come on back, help me start preparing this report. See you Tuesday.”

The line went dead. And this time Bill just laughed.

The following three weeks, which he spent in the United States, went by very fast. The detailed intelligence report Baldridge compiled with Arnold Morgan on the destruction of the USS Thomas Jefferson would become a case document for Naval investigations for years to come.

In the middle of Bill’s third week at home, the Mossad made another major breakthrough. General Gavron called Admiral Morgan to report that they had traced Ingrid. On April 7, she and her bagman, Kamel Rasheed, had checked into the Pera Palas Oteli, off the great pedestrian walkway of Istiklal Caddesi.

They had stayed two nights, checked out on the morning of April 9. The rooms had been reserved with an American Express card which the hotel had not checked. Then Ingrid had deposited $1,500 in cash on arrival.

Ingrid had dined alone in the hotel restaurant on both nights. No charges were forwarded to American Express, and there was no trace of either billing or payment. By the time the Mossad got hold of the number, the card was obsolete. And American Express would disclose nothing.

Nonetheless, Ingrid Jaschke, the Iraqi courier, was suddenly in Istanbul five days before Kilo 630 set sail.

Arnold Morgan liked what he now knew. He liked Ingrid’s sudden presence in Istanbul. He liked the man fitting Adnam’s description who made an overnight run to the Turkish border just hours before the Kilo sailed. “A thousand coincidences,” he grunted at Bill Baldridge. “They gotta add up to something. And right now they’re telling me our man Adnam is an Iraqi. No wonder Gavron’s upset. Those Israeli military guys hate their organizations being penetrated. Especially by a country like Iraq. I shouldn’t be surprised if they do our dirty work for us in the end.”

He walked over to his chart desk and stared again at the map of the northeast coast of Turkey. Once more he stuck the prong of his dividers into the now-worn pinhole at the Turkish port of Trabzon. The other end he placed on the resort harbor of Sinop. “Two hundred and thirty-five miles,” he muttered. “With a coastal road joining the two towns.”

He glared now at the coastal navigation chart, noting the jutting point of Sinop, the most northerly headland on this stretch of coast, so close, so conveniently close, to a deep-water submarine waiting area. “That’s where they picked Adnam up.”

“Sir?” said Bill.

“Oh, nothing. Just imagining Adnam’s point of departure. If your man Tomas drove him that night, I’ll bet there was a moored yacht missing from Sinop harbor a coupla days later. I gotta feeling about that place.”

The British Airways flight from London touched down at Istanbul’s International Airport late afternoon, September 7. Admiral Sir Iain MacLean stepped out of the first-class cabin, accompanied by a steward carrying his old dark leather suitcase. They made their way briskly to the immigration desks, where Lieutenant Commander Bill Baldridge waited.

The admiral’s passport was stamped quickly, and they were escorted through customs and into the car Bill had hired from the hotel.

Baldridge had also arranged for a corner table in the hotel restaurant, where the two could speak privately. They were due to board the Turkish pilot boat around lunchtime the following day, when they would join HMS Unseen as she sailed up from the Sea of Marmara to the Bosporus. The admiral said Unseen was scheduled to clear the Dardanelles at 2100, and would make ten knots toward Istanbul throughout the night and morning, a distance of 150 miles.

Before they went down to the dining room, the admiral presented Bill with a double-CD pack of Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen. The recording was sung by Agnes Baltsa and José Carreras, with maestro von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. “Bill, Laura gave me this for you. It’s the one you wanted and apparently asked for on your first visit. She said to say sorry it took so long, but she had to order it specially.”

Bill, who had not the slightest idea what Sir Iain was talking about, made a sharp recovery, and asked him to thank her very much. “I couldn’t get this recording in the USA,” he said. “It was good of her to go to so much trouble.”

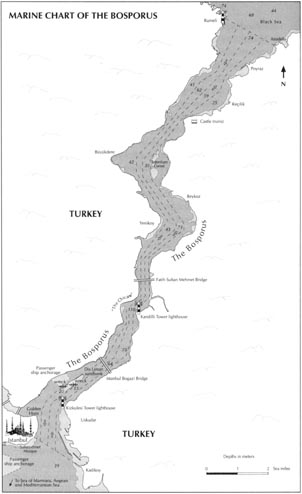

He placed the CDs on his bedside table, and left, joining the admiral outside the elevator. On the way he asked the question which had been concerning him for several weeks. “Sir, if the Turks sweep the Bosporus with radar, from one end to the other, as they claim, does this mean we can’t come up to periscope depth without running a risk of being detected? I mean, that mast on the Upholder will leave a damn great wake—surely they’ll spot us easily, maybe without even using radar, if they are alert.”

“Yes. They do sweep the surface of the Bosporus pretty thoroughly. And since I want to stay at PD for much of the way, we’ll have to box a bit clever.”

“Sure will. But what do we do? What did Adnam do?”

“He almost certainly did what I intend to do. He got into position in a southwesterly holding area in the Black Sea, and he waited for a good-sized freighter to show up with the kind of cargo to suggest it was going right through. Then he took a range on its stern light to get on the correct angle, and distance, and he tucked right into its wake, about a hundred yards behind. He set engine revolutions to match speed, and followed it through.”

“Gottit. His periscope wake obscured by the much bigger wake of the freighter?”

“That’s it.”

“We gonna do that?”

“We are.”

“Jesus. What if he stops suddenly, or goes off course, through water deep enough for him, but too shallow for us? We’ll either run straight up his backside, or hit the bottom.”

“We will if we are not careful. But we are going to be careful. That’s what Ben Adnam must have done. That’s what we’re going to do.”

“Is Jeremy Shaw up to this?”

“Oh yes, he’s extremely good. And he’s used to doing precisely what he’s told. I know his Teacher. Actually I taught his Teacher. And he was young Shaw’s boss for a good many years. Those old Navy habits die hard, thank God.”

“When do you want us in position?”

“Well, I think we should vanish from sight an hour north of the Bosporus. Just so no one has the slightest idea where we are. The Turks will see us come through on the surface, but as the light starts to fade, we will disappear.

“Then, I’d like to be at our Black Sea station, set up and ready, periscope depth, just before dark, around 1930, about thirty-five miles north of the Bosporus entrance. Just so we have enough light to identify a freighter making ten knots in the correct direction, hopefully going right through to the Med.

“We’ll get in behind him. Then we can snort down to the entrance, at PD, get a good charge into the battery, and hope the merchantman doesn’t see us. He probably won’t, because the light will have gone completely within a half hour of our picking him up. With a bit of luck.”

Bill shook his head, and smiled. “Guess I’m talking to the von Karajan of the deep.”

“Who’s he?” grunted the admiral. “U-boats?”

“No, sir. He’s the conductor on the CD Laura sent me. One of the best ever. Maestro Herbert von Karajan.”

“Oh yes, I see. Of course. I’m not much good at opera, really. But it’s good of you to say so, even though it’s not true. I’m just a retired officer volunteering for a job no one else wants.”

“As the personal choice of the Flag Officer of the entire Royal Navy Submarine Service, sir.”

“Yes. Of course, I used to be his boss, too. He’s probably trying to get his own back.”

Dinner was subdued. The topic of conversation was anchored in their own anxieties about the perilous task they faced tomorrow. Bill had never been involved in a crash-stop in a submarine, and he finally summoned the courage to ask the admiral how it worked. He did not mention the real question he wanted to ask—what do we have to do to avoid slamming right into the freighter’s massive propellers?

“It’s only dramatic if you’re not ready,” replied the admiral. “Which makes your sonar team even more critical than usual. They have one vital task—to issue instant warning of any speed change, the slightest indication that the freighter is reducing its engine revolutions.

“Which means they have to keep a close check on the freighter’s props. If she slows, we’re talking split seconds, otherwise we will charge right into her rear end, which is apt to be rather bad news.

“If the water’s deep enough, we will slow down, dive, and try to duck right under him. If it’s not, and there’s a bit of room out to the side, we’ll go for the gap. If there’s not enough water, no room to the side, and we’re late slowing down, I think you’ll probably end up at Jeremy Shaw’s court-martial. If any of us survive it, that is.”

“Christ,” said Bill. “Are there any procedures I ought to know about if we have to stop in a hurry?”

“There are a couple of things. All the time we are close to the freighter, we will want to be at diving stations. But we must be on top-line to shut down to a specially modified collision station.

“None of us knows much about the water density changes, and we have no idea if we’ll be in vertical swirls. So we may need old-style trimming parties. That means our watertight doors have to be open for them at all times, so the men can go for’ard or aft at high speed to help keep the boat level.

“I have had several talks with Jeremy Shaw, and I have recommended he posts bulkhead sentries throughout. Everyone will be on permanent standby. However, when we broadcast ‘crash-stop,’ the bulkhead doors will not be shut and clipped. They’ll be open for the trimming parties.”

Bill chewed his kebab thoughtfully, and then took a long swallow of red Turkish wine. He had never operated in a diesel-electric submarine, but he knew the basic collision procedures. In any tricky situation, the bulkhead doors should be kept shut and clipped in order to contain fire, or onrushing water if the submarine crashes or is holed. He knew too the terrifying dangers, especially if they were running deep.

The admiral remained sanguine, chatting away cheerfully about hair-raising scenarios below the surface of the Bosporus. “Actually, Bill, I’m hoping we’ll get a bit of practice quite early on if the freighter stops to pick up a pilot at the northern end. We’ll be right up his backside at that point, with the current sweeping us down the channel. Then we’ll find out how quick we are, and how easy it is to hold the trim, when two and a half thousand tons of steel traveling at ten knots suddenly slows down.”

Bill took another swig of wine, and they remained in the dining room for only another few minutes before returning to their rooms and turning in for the night. “Possibly my last night,” Bill said as he shut and clipped the bulkhead door of room 1045.

He opened the CD pack, and took out the two slim, sealed plastic holders and the glossy libretto booklet. No obvious message there. No note from Laura. He tipped up the outer box. Nothing there either. Then he began to leaf through the booklet.

He found it stapled to page 105. It read very simply:

I am back in Edinburgh now, and feeling a bit desolate not being able to talk to you. Please, Bill, look after my father, and for God’s sake look after yourself. I don’t think I could bear it if anything should happen to you both.

She signed it, “Laura” and placed a small line of three crosses beneath her signature.

But beneath the note were greater depths. Outlined in a pink highlighter were three lines sung by Carmen in the divine duet with Carreras during the ninth scene of Act One—translated from the French: “It’s not forbidden to think! I’m thinking of a certain officer who loves me, and whom in my turn, I might very well love!”

“That Bizet,” said Bill. “A guy with real perception.”

After a night disturbed by nerve-racked dreams, he felt unaccountably full of energy when finally he packed his bag and headed downstairs to meet the admiral. He paid both accounts with a credit card, and they headed down to the docks in a cab.

The ride out through the harbor, south along the Sea of Marmara, afforded them a spectacular view of Istanbul, the great pointed minarets of the Blue Mosque, Hagia Sophia, and the Topkapi Palace. The specter of the giant Bogazi Road Bridge, which spans the Bosporus three miles upstream from the Golden Horn, shimmered in a light heat-mist this morning as cars streamed across, two hundred feet above the water.

The captain of HMS Unseen held her stationary in the current just north of the Turkish Naval anchorage on the Asian bank. In flat, calm water Bill Baldridge, the admiral, and the pilot made their ship-to-ship transfer, bags being hauled by sailors with hooked ropes.

Both officers and the Turkish pilot expertly climbed the rope ladder, and were helped up onto the casing by two brawny young lieutenants. The newcomers joined Lieutenant Commander Jeremy Shaw on the bridge for the surface ride north through the Bosporus.

The CO greeted Admiral MacLean with the due deference Bill Baldridge had witnessed in all of his travels. He was more welcoming to Bill, and briefly outlined the high points of the long journey out from Barrow-in-Furness to Turkey. He was pleased with the submarine, and the crew had easily mastered the systems in the two-week workup period before they left England. It usually takes five weeks, but of course on this occasion they had not had to bother with weapons.

The ride north was highly instructive. Admiral MacLean assessed the width of the channel, the lights on the two big bridges, particularly those on the much narrower one, three miles north of the Bogazi, the Fatih Sultan Mehmet, already nicknamed by Unseen’s crew as the “Fatty Sultan.”

He noted the water depths in the narrow right-left “chicane” immediately south of the bridge, marked by the navigation control station at Kandilli, on the Asian side. The first big corner they would meet, a hard left and then a hard right, was equally as dangerous because the channels narrowed dramatically. The admiral took notes in small neat handwriting: “two bloody great shoals to port, five meters only.”

The sunlit waters of the Bosporus seemed wide on the surface, and not at all menacing. Only the charts revealed the hazardous nature of the seabed below. All the way north, Admiral MacLean was trying to establish the treacherous shape of the underwater contours.

Two hours after they set sail, Unseen cleared the Bosporus, and the men on the bridge said good-bye to the disembarking pilot. Then Captain Shaw ordered a northerly course, zero-three-zero, across a calm sea to their waiting point.

At 1730, Captain Shaw decided they should vanish: “Officer of the Watch, dive the submarine.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

“Clear the bridge.”

“Upper lid shut, one clip…both clips on.”

“Open main vents…Group up…half ahead main motor.”

“Main vents open, sir…Telegraph to half ahead…Group up, sir.”

“Five down. Seventeen and a half meters.”

“Twelve meters, sir.”

“Ease the bubble, Cox’n.”

“Eighteen meters. Bubble forward, sir.”

“Very good. Shut main vents. Group down.”

“Up ESM…particularly looking for commercial X-band radars coming in from the north, say three-one-five to zero-four-five.”

“Looks a pretty good trim,” said Captain Shaw. “I want you to stay in this position while we find a merchantman heading for the Bosporus. He’ll want to be under ten knots. An eight-knotter will do us fine. Stay reasonably furtive. Though he won’t be looking for the likes of us. Tell me if you get one, please.”

“Aye, sir. Blue watch…watch diving…patrol quiet state.”

“I’ll be in the wardroom with the admiral and our American guest. You have the ship, Number One.”

“I have the ship, sir.”

The Commanding Officer, the admiral, and Lieutenant Commander Baldridge immediately retired to the wardroom for a conference.

“The bottom’s mostly marked as shingle, Admiral,” the C.O. said. “We don’t want to be stern-down if we hit it. The trimming parties are going to be very important to us. But I can’t help feeling that in the narrows a lot of that shingle will turn out to be rock, which could be very nasty. Thus, I intend to stay at periscope depth, at almost any cost, well outside normal rules.”

“I think you need my written approval for that, Jeremy,” said Admiral MacLean. “I’ll enter it in the log. But I do agree with you—it’d be much better to write off a periscope on the bottom of a freighter, than leave yourself with a bloody great rock shoved straight through the hull.”

The three men stared at the chart. Jeremy Shaw was frowning, and said suddenly, “The tricky bits are here…here…and here.” He pointed to the big sharp bends with his index finger. We are going to call them Tattenham Corner—after the left-hander on the English Derby racecourse—and the Chicane. Usual reasons. Men under a lot of pressure often react faster to familiar words. These places are all unpronounceable Turkish, and represent mass confusion to everyone.”

“Good idea,” said the admiral.

“On the left-handers here I expect our leading freighter to keep right and not cut the corners. But he may be tempted to do so if there’s nothing coming up the other way. If he stops or does something bloody silly, and I can’t stop, or get under him, I’ll evade to port. And that’s when we may have to correct trim in a big hurry.”

“Yes, Jeremy. But if we have to evade, and there is a queue coming up the other way, I think we’d be better to surface astern of him, for a bit more control. You never know, he might not even notice. Amazing what you can get away with if you have enough brass nerve.”

“Yes,” Bill chimed in. “I once heard of a really insolent British warship getting right up to one of our carriers disguised as a curry-house.”

Jeremy Shaw burst out laughing. The admiral feigned innocence. “What about depths, Jeremy?” he said.

“Well, sir, we need seventeen and a half meters to run at periscope depth, plus five meters below…about twenty-two and a half meters minimum. The worst bit, easily, is right below the Bogazi Bridge, where the chart shows twenty-seven meters, but there’s a couple of wrecks marked right in the middle of the channel, one of ’em only fifteen meters below the surface.

“Right there, I can’t go to the right, because of the mooring buoys, and the merchant-ship anchorage. I can’t go down the middle because of the wrecks, and I can’t go left, because you can’t see round the big bend. This makes the other lane very, very dangerous. Not least because it’s only thirty meters deep anyway, which would prevent us ducking under a big oncoming freighter.

“If our leader looks as if he’s going to drive straight over the wrecks, I think we’ll have to surface, for a half-mile, only three minutes. Trouble is, it’ll be damned bright up there from the shore lights. That’s where the Turks might spot us.”

“I suppose we’ll just have to keep our fingers crossed, then,” said Sir Iain. “And hope for the bloody best. By the way, have you got a personal list of ‘call off’ factors, Jeremy? Like visibility, etc.”

“Just the usual things, sir. Defects on the nav system, losing our leader early on, before the last narrows, the Turks making it damned obvious they’ve seen us, or if trimming the ship is just too damned difficult in the currents. Aside from those, anything sudden, unexpected, which takes us beyond the last limit of our already-stretched margins for error.

“Basically, if the unforeseens pile up on us, until we have no way out. I’m hoping to rely on you and Bill to bear all those things in mind, while I get on with the minute-to-minute detail.”

“Good. We’ll just stand at the back with our teeth gritted until we can’t stand it another minute. You do have final responsibility for your ship, Jeremy, but I can’t help feeling I’ve put you here.

“Remember, you can always say, ‘Stop, I want to get off,’ and no one will think worse of you. We’re only here to see if this is possible; not to give a concrete demonstration that it’s not.”

“Okay, sir. I’m going to the control room for a look. Supper at eight. No wardroom film tonight, I’m afraid. Not even for the first-class passengers.” But they had a long wait…

092025SEPT02. 41.55N, 29.37E.

Course 180. Speed 5. HMS Unseen.

“Captain, sir. I have a possible…zero-two-zero…fifteen thousand yards…I’m about twenty on his starboard bow radar…gives him 8.5 knots on 180…we’ve got a strong commercial nav radar right on the bearing…no other traffic within five miles…turning toward for a proper look before the light goes altogether.”

“Right. I have the ship.”

“You have the ship, sir. His higher masthead light comes out at twenty-eight meters by comparison with radar, sir.”

“Okay. Up periscope. All round look.

“Target setup. Up. Bearing that…zero-two-two. Range that…on twenty-eight meters. Fourteen and a half thousand yards, sir…put me twenty-five on his starboard bow…target course one eighty-five…distance off track six thousand yards…

“Group up…half ahead main motor. Revolutions six zero…five down…forty meters…turn starboard zero-nine-five.

“Team…I’m going to run in deep to close the track for fifteen minutes. We want a good look as he passes on his way south. Then we’ll turn in behind and follow him…Make a broadcast, Number One…we’re going to be at diving stations from about 2030. And it’s going to be a long stretch. Eight or nine hours. Fix cocoa and sandwiches for 2300 and 0300.”

092040SEPT02.

“Take a look, Admiral. I think she’ll do. I’d say about six thousand tons. Small container ship…nationality Russian, from what I could make out on her funnel.

“She might not be going right through. But she fits nicely for time and speed. I think I’ll just swerve back in under her, check her draft while there’s plenty of water. Then I’ll slot in behind at PD.”

“Very good, Jeremy. She’ll do.”

HMS Unseen proceeded to match the freighter’s speed at forty-two revolutions, 8.2 knots, and began to track the Russians back toward the entrance to the Bosporus. They ran for almost four hours, and shortly after midnight at 0030 Captain Jeremy Shaw got his visual fix.

“GPS and soundings all tie in, Admiral. Rumineleferi Fort bears two-four-zero…two miles. Leader still on one-eight-two…eighty revolutions, making 8.7 over the ground, 8.2 through the water. Current’s behind us, should go to one knot in the next two miles. Expecting our leader to come right, to about two-one-seven, any second…

“There he goes, sir. Starboard three. Call out ship’s head every two degrees please.”

“One-eight-four…one-eight-six.”

“We’re up close, Admiral. Bow right behind his stern. Range locked on his stern light.”

“We have about twelve minutes on this course before he picks up his pilot.”

Locked together, traveling at precisely the same speed, the Russian freighter and the Royal Navy submarine headed on down to the Bosporus, separated by only one hundred yards of white foaming water, the bright phosphorescence gleaming in the pale moonlight.

No one in the merchant ship noticed the periscope sliding through the wake, as they were tracked along their course, unwittingly leading the aptly named Unseen into a kind of Naval history.

The degree of precision being practiced by the officers of the underwater boat would have been beyond the comprehension of even the most experienced merchant seaman. They kept station to the nearest few yards, observing the angle of the beam on the freighter’s stern light, knowing that if it increased they were going too fast and dangerously close-in. If it decreased, they were slipping behind and out of the wake.

They cleared the northern limit to the Bosporus, crossing the unseen line which stretches from the fort to the headland of Anadolu, with its light flashing every twenty seconds. They ran on down the channel for another two and a half miles before the freighter began to slow down for the pilot pickup.

Jeremy Shaw was ready. They had already picked up the revs of the fast diesel pilot boat, and when the submarine captain ordered the “crash-stop” it was accomplished with maximum efficiency with nearly two hundred feet of water below the keel. As it happened, Unseen came to a halt more quickly than the freighter. So far so good.

They ran on south in the pitch-black depths of the water, rounding the big left and right turns, still at periscope depth, right behind the freighter. They slipped under the “Fatty Sultan” at 0130, and prepared to meet the sudden right-and-left turn of the “chicane” off Kandilli, where the channel was narrow but deep, and the current fast and awkward.

But the freighter skipper steered steady and true, straight down the middle of the lane. He kept his speed constant, and the unseen watchers a hundred yards astern detected no alteration in the revs of his engines. No one was yet aware of the covert Anglo-American submarine operation. Above Unseen the military radar of Turkey swept silently over the water, but nothing locked onto the lone periscope slipping along in the turbulent white water which marked the trail of the freighter.

Jeremy Shaw eased the helm, steering course two-three-two, as they came into another straight area, where the channel grew more shallow, with the great span of the Bogazi Bridge almost overhead. They had been unbelievably lucky.

Through the periscope, Unseen’s CO could now see the yellow quick-flash of the bridge light to starboard, and the quick-white to port. The span passed overhead at 0141. A ferry crossed west to east up ahead, but well clear of the oncoming freighter and her shadow.

They were two minutes short of the shallow sandbank in the middle of the south lane—the one with two wrecks already on it—when the first danger signal flickered into life. Up ahead, running hard toward them, almost on the middle line of the shipping lanes, was an oncoming contact. They could see she was very wide on her course, going fast, rounding the right-hand corner marked by the Kizkulesi tower. What they did not know, at this stage, was that she was a twenty-thousand-ton Rumanian tanker.

The submarine would meet her just as they too had to swerve to the center to avoid the second wreck. There was not sufficient water here to go deep and get under her. There was only thirty meters at best charted on the edge of the shoal. The tanker drew about ten meters. Unseen would need at least twenty more.

Admiral MacLean and Jeremy Shaw had about five minutes to come up with something. Their options were running out.

“Christ! This thing is a fucking size,” the CO reported as he peered again through the periscope.

Then, just to compound matters, he spotted what looked like another ferry up ahead, crossing east to west right in their path. Then the totally unthinkable happened. The sonar officer called suddenly, “Control Sonar…our leader’s revolutions are decreasing, sir.”

Jeremy Shaw showed signs of real strain for the first time. “Jesus!” he exclaimed. “We really do not need this. No wonder it’s fucking illegal.”

Unseen was now on an underwater collision course with the Russian freighter’s screws, a life-threatening maneuver for everyone who sailed in the submarine.

Captain Shaw recovered his composure…“Revolutions twenty…turn fast starboard two-four-zero.”

Now the Russian freighter too began a long starboard swing toward the docks on the European side, but at least he kept going. The navigator called out that the fifteen-meter wreck was passed. But the Rumanian tanker kept coming, five hundred yards now, still too wide.

Jeremy Shaw and Admiral MacLean knew the shallow-drafted ferry could go straight over the casing provided it missed the fin and periscopes. But if the submarine pressed on down the left side of the down lane, they would be unable to avoid being mowed down by the Rumanians, who were not only blind to the submarine, they were running too wide and too fast.

Unseen was unable to move right because of the shoal and the twenty-meter wreck, unable to veer left because that would take her onto the Kizkulesi bend, and, while the tanker might miss them, they had no way of knowing that another big merchant ship was not driving round on the inside of the bend.

All the admiral could do was to suggest they make like a “dead pig”—that is, show as little periscope as possible, drifting just below the surface with the south-running current, easing over the sandbank, making no speed until they could go deep around the next corner. “That should keep us marginally out of the line of collision with the tanker, and the Turkish radar operators will take us for a hunk of flotsam,” said the admiral.

“If their helmsman makes even one minor mistake, he’s going to break this submarine into two very large pieces,” muttered the captain.

It was a passive maneuver, and the more courageous for that. But it was their only option. Within seconds they heard the propeller of the big tanker come thrashing down their port side, missing them not by the two hundred yards Admiral MacLean had estimated—cutting his normal safety margin by 60 percent—but by about forty yards.

The swirling turbulence in the wake of this massive hull, twenty thousand tons of steel barging through the narrow waterway, threw the submarine well off-course. She swiveled fifteen degrees to port before she steadied. “Ah yes, we’re heading straight toward Asia now—that was rather a novel way of doing it,” the admiral muttered.

“Not so bad, sir,” said the navigator. “We’re a bit late for our turn to the south round this bend anyway. I’m happy on the western side of the channel. The water’s deeper.”

Just then, a new call rang out in the Royal Navy submarine, which was still making like a “dead pig,” with only her periscope showing intermittently. “Control Sonar…new contact! Designated track four-three. Bearing one-eight-five.”

“Christ!” snapped the CO. “This is a big bastard and we’re right ahead of him, bang in his path. Put him at seven hundred yards. Give him twelve knots. Bloody hell, he’s in the wrong lane.”

“We’ll have to go deep,” snapped Admiral MacLean. “Jeremy…half ahead…four zero revolutions…five down…thirty meters…call out the speed.”

“Sir…”

“Two knots.”

“Christ. He’s turning. Midships. Starboard thirty.”

The CO barked, “Down all masts. Ease to ten…steer one-eight-three…thirty-one meters.”

“Twenty-five, sir.”

Then the sounder called the depth below the keel, “Sounding ten meters, sir.”

“Slow ahead.”

“Still one-eight-five. He’s louder. All other contacts blanked.”

“Thirty-one meters, sir.”

“Sounding five meters, sir.”

The admiral: “Yes, here he comes, Jeremy. That’s his bow pressure pushing us down. Foreplanes full rise.”

“Sounding two meters, sir.”

“Nice and level, Jeremy. Don’t want to put the propeller in the mud.”

“Right, sir. Depth holding…that’s the suction along his hull.”

The admiral gave out his last commands: “Half-ahead. Four zero revolutions. Seventeen and a half meters…but keep her level at first, Jeremy.”

The words of the sounding operator—“Two meters, sir”—were almost drowned out in the roar of the big freighter’s props as she thundered overhead, charging through the water at twelve knots.

“Track four-three right astern. Bearing zero-zero-four, sir. Very loud. Doppler low. Same revolutions, one-two-four.”

Admiral MacLean stepped aside as the submarine headed back up toward the surface of the mile-wide and now deeper waters of the harbor of Istanbul. Slowly Unseen climbed to periscope depth as she silently entered safer waters.

Fifteen minutes after the near-miss, life was just about back to normal in the control room and plainly the worst was over. Captain Shaw handed over to his first lieutenant, joined the admiral and Baldridge for a cup of tea in the wardroom.

“I’m sorry I was a bit pushy there, Jeremy,” said Admiral MacLean. “But I reckoned I’d seen a lot more of those shallow-water, close-quarters situations than you had.”

“Absolutely, sir. I was getting a bit mesmerized looking through the periscope. Anyway I think I had missed the navigator’s clue that we were in deeper water, and could go under him. Thank you, sir.”

Unseen headed out of the wide southerly channel which flowed past the eastern shoreline of the old city of Istanbul. There was more than fifty meters of water here, and less than three miles to the open reaches of the Sea of Marmara.

Jeremy Shaw wondered when they should send in a satellite message to the duty officer in Northwood. “And one to Washington?”

“I’d say we ought to do it right away,” said the admiral. “We’ve done it. And that’s that.”

“Do you have a code word for a successful mission, Bill?” asked the captain.

“Sure do—home run—that’s what they’re waiting for. Straight to Admiral Morgan, Fort Meade, Maryland. It’s nine o’clock at night there, but he’ll be around in his office, waiting to hear.”

The CO sent for a messenger to take a drafted signal for transmission. Then he left the wardroom, leaving the admiral and Bill alone.

“Let me ask you something, sir. Would you have done it, if you had known in advance what it was going to be like?”

“No, Bill. I would not. I understood the risks, but I did not think we would run out of luck quite so often! We were nearly killed twice in ten minutes. That first freighter that nearly hit us was closer than I have ever been to death. I actually thought the second one was going right through us.”

“If it hadn’t been for you, sir, she might have.”

“Oh, I expect Jeremy would have thought of something in time.”

“Well, I was pretty glad we did not have to hang around and find that out, sir. You saved us. So did Jeremy. And all you have to show for it is a bit of history. Senior officer in the first submarine ever to transit the Bosporus underwater.”

“Not even that, Bill. We were the second.”

Admiral Arnold Morgan received the signal with delight. “Home run.” They’re through. He called Scott Dunsmore to break the news. In turn the CNO called General Josh Paul, who informed him the President awaited his call, and that the admiral should make it personally. One minute later, the President stepped out of a formal dinner to speak on the telephone to his Chief of Naval Operations.

“They did it?…Good…Yes, you have my full authorization to commit resources to find and destroy the Russian Kilo, using whatever means you must…I’ll leave that entirely to you…”

Admiral Dunsmore replied, “Thank you, Mr. President.”

“Go get ’em, Scott,” said the Chief Executive.