271300MAY02. 6S, 73E.

Course 340. Speed 12.

SURROUNDED BY HIS MOST SENIOR STAFF, REAR ADMIRAL Zack Carson, one of the few high-ranking, seagoing officers in the United States Navy, was methodically grappling with a zillion details involving the waging of war on a scale never before witnessed on this particular planet.

He was seated in a king-sized leather chair in the Flag Operations Room on the third floor of the island, thirty feet above the five-acre flight deck of his flagship, the USS Thomas Jefferson.

They had moved generally WNW during the past two weeks in the Indian Ocean, and the huge aircraft carrier was now proceeding close-north of the remote tropical atoll of Diego Garcia. To the NNE, 850 miles away, stood the headland of Cape Comorin, the southernmost point of the Indian subcontinent. If, however, the Thomas Jefferson followed the polestar due north she would steam for 1,600 miles before entering her patrol zone in the Arabian Sea. Deep blue waters, shark-infested, some 450 miles due west of the teeming seaport of Bombay.

Admiral Carson was due on station in those tense, somewhat unpredictable seas eight days from now. His massive presence there, at the very gateway to the Gulf of Iran, served as a warning to all who might challenge the right of the world’s tankers to ply their trade along the sprawling crude oil terminals which stretch from the Strait of Hormuz to Iraq. His presence would also, unavoidably, deepen the already simmering hatred toward the United States by much of the Islamic nation. But that goes with the territory of a Battle Group Commander. And the six-foot-four-inch Kansan Zack Carson, at the age of fifty-six, had long since accepted that not everyone flew a flag of pure joy when his giant ship hove into sight along the horizons of the Middle East.

At his command were cruise missiles, guided weapons of all types to attack targets above, on, and under the water, a small all-purpose Air Force, whole batteries of artillery, to send in thousands of shells per hour. And stored deep in the bowels of this great ship, and in his two nuclear submarines, other missiles—missiles of such colossal destructive force, not even Zack Carson was comfortable contemplating the consequences of deploying them. The admiral, and his masters in the Pentagon, could, if instructed, damn nearly destroy much of the world. In very short order.

That was not an actual part of his plan, but a U.S. Battle Group must, at all times, be right at the peak of the warfare efficiency curve, which heads steeply upward according to the value of the hardware. The view of the Chiefs of Staff, not to mention the hard-nosed Southwestern Republican currently occupying the White House, was, broadly, “at that price it better work, and it better work real good, right on time, no bullshit.”

Thus, at this particular moment, in deep conversation with his fellow Kansan, Captain Jack Baldridge, Admiral Carson was making doubly sure that the previous month’s intense battle training programs had transformed this ship, and all of the six thousand men who sailed in her, into the best it was possible to be. From the cooks to the navigators, from the sonar men to the guys in the print room, from the firefighters to the fighter pilots, the radar wizards to the missile loaders—the Battle Group commander could afford no weak link in his chain of command, no suspect system, no indecisive officer, zero inefficiency. This was the very frontier of warfare, the bottom line of the U.S. offense and defensive charter. The admiral, reverting easily to the more relaxed vernacular of the prairies, often reminded his closest staff officers in the following way, “A long time before the buck comes to a stop in the Oval Office, someone’s gonna shove it right up my rear end.”

For weeks on end, the admiral had driven the entire Battle Group to the heights of their abilities. Twice a day he sent out communications detailing exercises which ultimately involved all sixteen thousand of the men serving in the dozen ships in the group.

There was endless training for the Aegis missile cruisers—training which ensured they really could knock out any incoming missiles, even traveling at twice the speed of sound.

The submarine commanders, ranging far out in front of the Battle Group, were made firmly aware of the admiral’s special interest in their work. He believed not only in the offensive capability of these search-and-strike underwater killers—but in their critical role as the group’s frontline anti-submarine weapon; the destroyer of their own counterparts. After several weeks out here, practicing and patrolling endlessly in the deep waters of the Indian Ocean, the phrase “deadly accurate” really did apply to all of their systems, but especially the lethal wire-guided torpedoes, equally effective against ship or submarine.

Zack Carson, a surface ship man and, in his youth, a former aviator, had often wished he had been a submariner. He was just never sure he could have passed the searching examination process these sailor-scientists require before taking command of a U.S. Navy SSN…the degree in marine engineering, the electronics, the mechanics, the hydrology, the deep navigational skills, and the nuclear engineering courses. These days the underwater commanders represented the elite of all Western navies, and Zack Carson was kind of uncertain that he possessed quite the academic grasp the submarine service required of its captains.

He had made his name as a battle line strategist, an expert in aviation, missiles, and gunnery, a tactician on the grand scale, a commanding officer who painted in broad, sure strokes, but never strayed too far from the minutiae of his trade. Everyone liked Admiral Carson, because he still sounded like some kind of a gunslinger from the High Plains of Kansas—as indeed a couple of his direct ancestors had been—and he displayed a deliberate, laid-back nonchalance under pressure that was plainly deceptive, but nonetheless an enviable quality in any ship’s operational center.

All of which was pretty impressive from a Midwestern farm boy who had grown up in the little town of Tribune, in the middle of the endless wheat prairies of Greeley County, hard by the western state border where Kansas joins Colorado. These lands summon up the true meaning of the word “nowhere.” Flat, sprawling Greeley County contains only two small towns in its entire 620 square miles. Both of them are set along the little local highway, Route 156, which starts 180 miles to the east near the great bend of the Arkansas River.

These are the remotest American lands, with populations of about one hundredth the average for rural U.S.A. Miles and miles and miles of wheat and grassland, flat, windswept, and, in an uncluttered way, made glorious by the sheer absence of spectacle. Out here, under the big sky, untouched by modern intrusion, names like Elija, Zachariah, Jethro, Willard, Jeremiah, and Ethan were commonplace. Zachariah Carson was the tall, lean son of Jethro Carson, who farmed thousands of acres of the prairie, as his immediate forefathers had also done.

Perhaps it was a young lifetime spent watching the wind sweep across the endless acres of gently waving wheat which gave Zack Carson his early longing for the ocean. But for as long as he could remember, he had an uncomplicated yearning to join the United States Navy. There were two other brothers in the family to carry on farming the wheat, but it almost broke old Jethro Carson’s heart when his oldest boy packed his bags at the age of eighteen and set off across the country from the most landlocked state in America for the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. His entry into the historic Navy school represented the biggest teaching triumph in the entire history of Tribune High.

With his gangling walk, crooked grin, and down-home way of expressing himself, Zack Carson proceeded to stun successive Navy examination boards with his grasp of the most intricate details of warfare at sea. He gave up Navy aviation after ditching a faulty jet fighter over the side of a carrier, when he was just twenty-six, and he commanded a frigate before his thirty-sixth birthday. He had charge of a guided missile destroyer at thirty-nine, and by the time he was forty-eight, Zack was captain of the giant carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower—named after another Kansas boy. This was most unusual for an aviator turned “black shoe”—but Zack was pretty unusual, too, and recognized as such.

They promoted him to rear admiral within four years and in the year 2000 awarded him the honor of the newest U.S. aircraft carrier, the Thomas Jefferson, for his flagship. Within a few months he requested as his Battle Group Operations Officer another Kansas farm boy, Captain Jack Baldridge, whose hometown of Burdett was about 120 miles from Tribune, straight along Route 156. Like Jack he was married with two daughters, and both families now lived in San Diego, California, where the Thomas Jefferson was based.

Baldridge was a barrel-chested disciplinarian who reacted swiftly and decisively to any possible threat or danger to his ships. Admiral Carson was more inclined to give a few “Uh-huhs.” Under pressure, Admiral Carson was cautious, thoughtful, cynical, and superstitious. He was also absolutely decisive.

They made a truly formidable team. When either of them spoke, the Combat Information Center jumped. Because when Captain Baldridge issued an order, that was an order from the admiral himself. And in a big-deck carrier that was an order that was seldom questioned.

Right now the two of them were discussing the possibility of yet another heavy night-flying program, as part of the major upcoming war game against the U.S. Battle Group they would soon be replacing in the Arabian Sea. The battle lines were now being drawn, and as ever these apparent practice sessions were taken with immense seriousness by all concerned. Because this was their opportunity to hone their battle skills in a theater of almost real war.

These exercises are both career breakers and makers. They are blisteringly expensive, and represent the only way the U.S. Navy has to simulate battle conditions, and to assess various key players and how they will react to the heightened speed and danger of the exercise. In the forthcoming combat zone, the Thomas Jefferson would attack the resident, and now outgoing, Battle Group centered on her fellow Nimitz-Class 100,000-tonner, the USS George Washington.

A time is set for the “attack” to begin and from then on the aggressor will use every piece of electronic guile, cunning, and naval hardware to get in close to the opposing carrier and “kill” her. No one actually fires a shell, or launches a missile, or even drops a bomb, but that’s what it feels like for the defenders when they pick up the telephone to hear the fatal communication. “Admiral, we regret to inform you, our submarine is three miles off your starboard beam, and three minutes ago we fired two torpedoes, both nuclear. You are history. Good morning, we’ll drop in for a cup of coffee later!”

Between the start and the completion of the three-day exercise, there are constant air “attacks” on the missile ships; computer and radar systems are tuned to record every detail, and every department throughout the fleet is monitored assiduously. The normal opening moves involve careful reconnaissance and probing, to establish the enemy group’s disposition, layout, and makeup. Step two is to deduce the enemy’s intentions and likely battle plan, while concealing yours from him. The normal outcome is a “victory” for the defenders because it really is almost impossible to get close to a carrier. And her missile men pick off the incoming attacks in pretty short order. They also “sink” a few ships and submarines while they are about it.

The Hawkeye radar station in the sky can see for so many hundreds of miles, an undetected attack above water is a great rarity. However, there are always instances of a Carrier Group’s outer layers being penetrated in these exercises, and the consequences are extremely uncomfortable for the “losing” commanders. No purely defensive measures are ever 100 percent effective. The occasional “leaker” will sometimes get through.

The vital question is, can he do any damage once he gets in? If he does, there will be, without doubt, a major postmortem, and there is always the unspoken threat that the exercise was in fact a high-level examination to identify future senior battle commanders. For the Navy brass there is of course the solace that it took one U.S. Battle Group to sink another. No one else could play in the same league. Nonetheless, defending commanders in these multimillion-dollar war games feel themselves to be on trial, and they expect no mercy from their opponents.

Which was, essentially, why Admiral Zack Carson and Captain Jack Baldridge were currently locked in conference with several of their senior departmental chiefs, deciding whether to order yet another night-flying exercise off the carrier, knowing how tired many of the pilots and air crews already were.

Opinion was just about divided on whether it was really necessary, but Captain Baldridge was an old acquaintance of his opposite number in the George Washington. “That sonofabitch will attack at night,” he said. “He won’t care how long he waits, he’ll come at us after dark. I know the guy. He’s as cunning as an old coon dog, hunts after dark, and we want CAP’s up there early, about a hundred miles up-threat. Nearly every goddamned problem we’ve had on the flight deck these past few weeks has been at night, and I think we should spend the next week keeping the pilots sharp.”

Admiral Carson said slowly, “Well, you guys, about eighteen years ago I knew an admiral who lost one of these war games to a small Royal Navy frigate group we were working with. Right out here in the Gulf of Arabia.

“The Brits lit up a destroyer like a Christmas tree, found some guy who could speak Bengalese, and made out like a tour ship. Next thing that happened they were on the line about two miles from the carrier, in clear weather, announcing they just fired half a dozen of those Exocet missiles of theirs, straight at the ole ‘mission critical’—a lot of people thought it was funny as hell. But not in Washington. It turned out to be a real embarrassment for that admiral. I could get by real easy without any of that bullshit breaking out here.

“So I’ll go with Jack. Start flying again tonight. Warn Arctic we want everyone topped up before dark.”

Moments later, even as the new night-flying orders were being prepared, the ship’s bush telegraph, which operates along the main upper deck where the pilots live, was buzzing. Squadrons were grouping together, pilots were razzing each other about shaky night landings, the Landing Signal Officers were checking schedules. Certain engineers and hydraulics specialists were already heading down to the gigantic hangars on the floor below—an area 35 feet high and 850 feet long, the overall size of three football fields.

This was the garage for the fighter/attack aircraft, the bombers and the surveillance planes. Also down here were the aviation maintenance departments and the jet engine repair shop. Directly above the for’ard end were the massive hydraulic steam rams for the catapults; above was the domain of Ensign Jim Adams, who would have First Watch as Arresting Gear Officer tonight.

Meanwhile the distant whine of engines being checked over was already beginning on the sweltering tropical heat of the flight deck, where the Tomcats, the Hornets, the deadly, all-weather Intruder surprise bomber, the EA-6B radar-jammer, and the ever-present Hawkeye, were being prepared once more to go to work.

271600MAY02. 15S, 3W.

Course 165. Speed 8.

“Okay, Ben, I’d say St. Helena is about a hundred miles off our starboard beam now. We better start looking for the tanker. Getting real low on fuel. He better show up.”

“He’ll be there, Georgy, in about two to three hours I’d guess, just before dark. We have not seen a ship for a week—so we’ll have the place to ourselves, I’d think.”

“This is a big ocean, Ben. Something go wrong down here, take six months to find us.”

“If something goes wrong down here, we don’t want anyone to find us. Better to swim to Africa. Remember what I told you about St. Helena. That’s where the English locked up Napoleon for six years after Waterloo. He died there. We might end up in his old cell. Keep going as quiet as you can.”

“I’m quiet, Ben. You have to admit that. No mistakes, eh?”

“One minor one, Georgy. Just that one, in the straits. Remember? I almost jumped out of my skin.”

“You jump more if we hit that tanker. I had to speed up, you know.”

“I’m not complaining, Georgy, but in that area the Americans are very, very thorough. Someone might have heard us.”

“For only twenty seconds, Ben.”

“That’ll do for the Americans. They are very alert to any mistake by anyone. Just hope no one noticed.”

“If anyone did they gave up a long time ago. Not even see aircraft for a week.”

“Well, that’s true. We’ll just take care, hold this speed and start looking for our fuel about two hours from now.”

“Okay, Ben, you’re the boss.”

290900MAY02. USS Thomas Jefferson.

5N, 68E. Course 325. Speed 30.

Midway between the Carlsberg Ridge

and the Maldives. 2,500 fathoms.

“Okay. Start time 1200 confirmed. George Washington about five hundred miles due north. That means her SSN’s might be as close as three hundred miles already. Order both our submarines into sectors northeast and northwest ASAP. And have everyone else on top line from 1000. I don’t trust their Group Ops Officer any better than he trusts me. He might just go ahead and start this thing right away, and no one will give a shit if we bleat. We take no chances.”

Captain Baldridge was glaring out over the Admiral’s Bridge, which was in pretty stark contrast to his boss, who was grappling with the crossword from the Sunday edition of the Wichita Eagle someone had sent up to him. “Easy, Jack,” he muttered. “They won’t close in on us before the start time. This is a heavy overhead area. Everyone would see. How about another cup of coffee? We’re ready.”

“Well, I don’t look for an incoming air strike till after dark, but I just don’t trust their submarines. I don’t trust any submarines except for the ones directly under our control. Those guys are brought up to be the sneakiest shits in the Navy. They can’t help themselves. And they know roughly where we are. So we might as well have a full active policy, every one of our sensors needs to be up and running, active and passive.”

Admiral Carson looked up, and said laconically, “Eight-letter word, starting with ‘T’—Devious Roman Emperor.”

“Mussolini,” growled Jack Baldridge, unhelpfully.

“Close. But I guess Tiberius might fit a bit better. He was a tricky old prick in his time.”

“Shoulda been a submariner,” said Baldridge, hiding his constant amazement at the obscure facts the admiral stored beneath that farm-boy thatch of straw hair. “Anyway I’m still taking no chances with the enemy’s submarines, and with your approval I’ll thicken up the ASW effort for the first thirty-six hours.”

“Go ahead, Jack, we don’t wanna get caught with our shorts down. But of course you won’t forget to bias it a bit west because we’ll be flying in that direction. Their SSN’s are always gonna be our major threat. You got that right.”

010430JUN02.

Billy-Ray Howell and the newly fit Freddie had already led the eight Tomcats home after “wiping out” the entire attack force of the George Washington—caught them 250 miles out, off the Hawkeye’s radar, but held their fire until they were sure. Both the enemy submarines had been located and “torpedoed,” one still a hundred miles from the carrier. The other was dispatched by a couple of anti-submarine helicopters when it was detected on radar, at periscope depth, twenty miles out.

“Too fucking close,” growled Captain Baldridge, somewhat ungraciously, to the operators. Then turning to the admiral he said, “Sneaky pricks, submariners. Told you. Never take a chance with those bastards.”

“You don’t need to remind me about ’em, Captain,” replied the admiral. “They’ve been a preoccupation of mine for years. I’m always darn glad to get ’em out of the way in these exercises. I’m almost like you. I don’t trust ’em. But I admire them, and you plain hate ’em.”

“Bastards,” confirmed Jack Baldridge.

And now the exercise was over, and the Jefferson had scored an overwhelming victory. Radar beams had crisscrossed the sky and ocean throughout the hours of darkness, and below the surface, the underwater men in the SSN’s had searched tenaciously for each other. Both of Admiral Carson’s submarines had survived the night intact, and the big Kansan had called the operation off just before dawn. He was within one hour of taking out the opposing carrier either with missiles or torpedoes. The George Washington had only one live escort left.

“Shoulda sunk ’em all,” muttered Baldridge.

“Not necessary,” said the admiral. “The record will be clear enough. I thought our guys, specially the pilots, were damned good tonight.”

The weather had turned bad shortly after midnight. There had been a lot of wind, and low, heavy clouds were making the landings more perilous than usual. One by one the fliers had brought them thundering into the deck. The hooks grabbed and connected every time.

With the wind on the increase and rain sweeping straight down the angled deck, they waited for the arrival of the last one—the Hawkeye, lumbering in from its high-altitude tour of duty. Ensign Adams, on another night watch as Arresting Gear Officer, was at his post on the pitching deck, watching for the dim navigation lights of the big radar aircraft.

The Landing Signal Officer standing right out on the port-quarter was in phone contact with the Hawkeye’s pilot, Lieutenant Mike Morley, an ex-Navy football tight-end, out of Georgia. Morley was good in any conditions, but he was at his best under real pressure, at night, in difficult weather. Right now he was following nighttime low-visibility landing procedures. He was coming in at 1,200 feet, six miles out.

The LSO attempted to instill confidence in the incoming crew. “Okay, Mike. Four-eight-zero, you’re looking great…watch your altitude…check your lineup…”

One mile out, the big E-2C Hawkeye was still right on the landing beam, and the LSO heard Morley say quietly: “Okay, I’ve got the ball. Nine thousand pounds.” They could now see the powerful beams of the landing lights on the aircraft’s wings, rushing in toward the stern of the carrier, rising and falling with the buffeting headwind. Everyone was on edge as the last of the Jefferson’s nighttime warriors came charging home.

Jim Adams shouted into the darkness, “Groove!” And now they could hear the howl of the props on the Hawkeye’s eighty-foot-wide wingspan as it bore down on the ship, an angry, glowing alien from space, made tolerable only by the design on its rear fuselage, the old familiar white star in the blue circle, the red stripe, and the single word: NAVY.

“Short,” yelled Adams, then seconds later, “Ramp!”—and Mike Morley flew the Jefferson’s battle-line quarterback fifteen feet above the stern, then hard into the deck, poised to open the throttle as the wheels slammed in, but hauling it closed as he felt the hook grab and the speed drop from 100 knots to zero in under three seconds. The scream of the engines drowned out the spontaneous roar of applause which broke out from several corners of the flight deck. There were beads of sweat on the forehead of Mike Morley, and he would never admit his heart rate to anyone. “Came in pretty good,” he drawled in his deep Southern voice, as he walked away from the Hawkeye. “Y’all did a real fine job gettin’ me down. Thanks, guys.”

171430JUN02. 26N, 48E.

Course 040. Speed 8.

“You sure we go outside the big island, Ben? Gets real rough out there.”

“Not, I assure you, as rough as it would get if we got caught between the island and the mainland. The Pacific Fleet patrols those waters these days. I do not think there is overhead surveillance, but I cannot risk being spotted by a U.S. warship. They are extremely jumpy at best. If they did see us, they would be very curious.”

“Yankee mother fuckers, hah? We stay away from them.”

“Yes, Georgy. For the time being we stay away from them—and everyone else for that matter.”

“What about next refuel? Under half left.”

“Well, this thing will go well over 7,000 miles at this speed. We’re around 1,750 from the Carlsberg Ridge. Then another 250 to our final refueling point. We’re fine, Georgy.”

“Okay, what’s that, another ten days before we look for tanker?”

“Exactly. Are the crew all right?”

“Not bad. It long and boring, but we change that soon, eh?”

“Remember your chaps, all fifty of them, understand they are conducting a critical mission on behalf of Mother Russia. You should perhaps remind them of that.”

“High risk though, Ben. I don’t think I ever see home again. Either way.”

“Maybe not home. But you will have a new one in another place. We will take care of everything.”

261200JUN02. 21N, 64E. Course 005. Speed 10.

On board the Thomas Jefferson.

Three weeks into their on-station time, Admiral Carson’s Battle Group was four hundred miles southwest of Karachi and six hundred miles southeast of the Strait of Hormuz, home of the Iranian Naval base of Bandar Abbas. To the west lay the coast of Oman, to the north, the deeply sinister mountain ranges which reach down to the coast of Baluchistan.

On the direct instructions of the admiral, Captain Baldridge had called a conference of the main warfare departmental chiefs. They were all there, sitting around the boardroom-sized table in the admiral’s ops room—the key operators from the Combat Information Center, the senior Tactical Action Officer, the Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer, the Anti-Air Warfare Officer, the Submarine Element Commander, Captain Rheinegen, the master of the carrier itself, Commander Bob Hulton, the Air Boss. From the rest of the group, there were six senior commanders, including Captain Art Barry, of the guided missile cruiser Arkansas, New York Yankees fan and buddy of Jack Baldridge. He had flown thirty miles, from the western outer edge of the group.

For several of them it was a first tour of duty in the Arabian Sea, and Zack Carson considered it important to let them all understand why they were there, and to impress upon their various staff officers the critical nature of this particular assignment. “Now I know it’s real hot out here, and there doesn’t appear to be that much going on,” he said.

“But I’m here to tell you guys that this is an extremely serious place to be right now. The tensions in the Middle East have never been a whole hell of a lot worse, not since 1990. And as usual ownership of the oil is at the bottom of it all—and I don’t need to tell you that every last barrel of the stuff comes right out past here—Jesus, there’s more tankers than fish around here as I expect you’ve noticed.

“The policy of the State Department is pretty simple. As long as we are sitting right here, high, wide, and handsome, no one is going to cause much of an uproar, no one’s going to monkey around with the free movement of the oil in and out of the Gulf. However, should we not show a U.S. presence in these waters, all hell could break loose.

“The Iranians hate the Iraqis and vice versa. The Israelis hate the Iraqis worse than the Iranians. The Iraqis are plenty crazy enough to take another shot at the Kuwaitis. The Saudis, for all their size and wealth, are damned badly organized, and they control the most important oil field on earth—the one brother Saddam was really after in 1990.

“I guess I don’t need to tell you how dangerous it would be for world peace if anything happened to take that big oil field out of the free market. I can tell you the consequences if you like—the United States and Great Britain and France and Germany and Japan would be obliged to join hands and go to war over that oil, even if we had to take the whole damned lot away from the Arab nations. And that would be kinda disruptive. I expect you recall that in 1991 the USA sent five Carrier Battle Groups into the area, enough to conquer, if necessary, the entire Arabian Peninsula.

“But, gentlemen, while we are here parked right offshore, and making the occasional visit inside the straits, no one, but no one, is going to try anything hasty. And if they should be so foolish as to make any kind of aggressive move, I may be obliged to remind them, on behalf of our Commander-in-Chief, that for two red cents we might be inclined to take the fuckers off the map. Last time I heard a direct quote from the President on this subject, he told the CJC he wanted no bullshit from any of the goddamned towelheads, whichever tribe they represented.

“Our task is to make sure that these areas of water where we are operating are clean, that the air and sea around us are sanitized. No threat, not from anyone. Not to anyone. That’s why Hawkeye stays on patrol almost the entire time. That’s why we keep an eye in the sky twenty-four hours a day, why the satellites keep watch, why we must ensure the surface and air plots are, at all times, clean and clear of unknowns, and hostiles.

“Because this, gentlemen, is real. Without us, the whole goddamned shooting match could dissolve. And our leaders would not like that—and, worse yet, they’ll blame us without hesitation. In short, gentlemen, we are making a major contribution to the maintenance of peace in this rathole. So let’s stay right on top of our game, ready at all times to deliver whatever punch may be necessary. The President expects it of us. The Chiefs of Staff expect it of us. And I expect it of you.

“I consider you guys to be the best team I ever worked with. So let’s stay very sharp. Watch every move anyone makes in this area. And go home in six weeks’ time with our heads high. I know a lot of people will never understand what we do. But we understand, and in the end, that’s what matters. Thank you, gentlemen, and now I’d be real grateful if you’d all come and have some lunch with me, ordered some steaks.”

Each of the men at the admiral’s table understood, perfectly, all of the political ramifications of the Middle East. And the potential danger to all American servicemen in the area. But they still required, occasionally, some personal confirmation of their prominent positions in the grand scheme of things. Which, given their relatively modest financial rewards, was not a hell of a lot to ask. And Zack Carson’s hard-edged, aw-shucks way of delivering that confirmation made him a towering hero among all of those who served under his command. Not most. All.

271500JUN02. 5N, 68E.

Course 355. Speed 3.

“I can hold this position three hours, Ben. But I sure hope tanker shows up soon. Fuel’s low, and crew know it. Not too good, hah? They get worried.”

“Not so worried as if they knew our precise mission, eh, Georgy? Tell ’em not to worry. The tanker will arrive inside four hours and she’ll show up right on our starboard bow—she must have cleared the Eight-Degree Channel early this morning, making a steady twelve knots. We’ll be full by 2100 and on our way north.”

280935JUN02. 21N, 62E.

Course 005. Speed 10. Ops Room.

Thomas Jefferson.

“Anyone checked the COD from DG? It’s supposed to have a ‘mission critical’ spare on board for the mirror landing sight.”

“I checked at 0600, but I’ll do it again before he takes off. They used another spare last night. It was the last one.”

281130JUN02. 9N, 67E.

Course 355. Speed 8.

200 miles from refueling point.

Officer of the Watch: “Captain in the control room.”

Georgy’s voice: “What is it?”

“Just spotted twin-engined aircraft, around thirty thousand feet—probably turboprop. Identical course to our own. I’m guessing U.S. Navy. He’s no threat. But you say secret journey.”

“Well done, Lieutenant. I come and look…

“…Hi, Ben, just taking a look at aircraft—he very high and going north, but my Officer of Watch thinks it U.S. Navy, and he probably right. That’s an American military turboprop for sure.”

“Well, what are you going to do about it?”

“Me? Nothing, Ben. That pilot just a truck driver. No threat to us.”

“That is the advice, Georgy, of a man whose nation has never fought a war in submarines. I’m going to tell you something, which I do not want you to forget. Ever. At least, not as long as you are working for me.

“It was taught to me by my Teacher…in this game, every man’s hand is against you. Assume every contact, however distant, has spotted you. Assume they will send someone after you. Usually sooner than you expect. Particularly if you are dealing with the Americans.”

“Let me take quick look again, Ben.”

“Do nothing of the kind. I already assume we have been sniffed by a U.S. Navy aircraft. We must now clear the datum. We take no chances. Georgy, come right to zero-five-zero. We’re going northeast toward the coast of India. Then, if they catch us again in the next couple of days, they will see our track headed for Bombay, and designate us Indian, therefore neutral, as opposed to unknown, possibly hostile.

“This detour will cost us one and a half days. But we’ll still be in business. Hold this course until I order a change.”

281400JUN02. 21N, 64E.

The Thomas Jefferson.

On patrol in the Arabian Sea, the Battle Group is spread out loosely in a fifty-mile radius. Up on the stern, one of the LSO’s is talking down an incoming aircraft, the COD from the base at Diego Garcia. It contains mail for all of the ships, plus a couple of sizable spare parts for one of the missile radar systems, plus two spares for the mirror landing sight. The pilot is an ex-Phantom aviator, and the veteran of three hundred carrier landings.

With an unusually light wind, calm sea, and perfect visibility, Lieutenant Joe Farrell from Pennsylvania thumped his aircraft down onto the deck and barely looked interested as the hook grabbed and held.

They towed her into a waiting berth beneath the island, and opened up the hold, while Lieutenant Farrell headed for a quick debrief, and some lunch after his four-hour flight. Right at the bulkhead, he heard a yell: “Hey, Joe, how ya been?”

Turning, he saw the grinning face of Lieutenant Rick Evans, the LSO who had talked him in. “Hey, Ricky, old buddy, how ya doin’—come and have a cup of coffee, it’s been a while—they made you an admiral yet?”

“Next week, so I hear,” chuckled the lieutenant. He and Farrell went back a long way, to the flight training school at Pensacola, seventeen years previously.

The two aviators strolled down toward the briefing room, and, as they did so, almost collided with Lieutenant William R. Howell, who was walking backward at the time sharing a joke with Captain Baldridge. “Hiya, Ricky,” said Billy-Ray. “We about done for today?”

“Just about. Hey, you know Lieutenant Joe Farrell, just arrived from DG with the mail and a couple of radar parts?”

“I think we met before,” said Billy-Ray cheerfully.

“Sure did,” replied Farrell. “I was at your wedding with the rest of the United States Navy.”

Everyone laughed, and Captain Baldridge stuck out his hand and said, “Glad to meet you, Lieutenant. I’m the Group Operations Officer, Jack Baldridge. Have a good flight up here?”

“Yessir. A lotta low monsoon cloud back to the south, but some long clear areas as well, no problems. Ton of tankers below.”

“Well, I’ll leave you guys to shoot the breeze…catch you later…”

“Oh, just one thing, sir,” said Farrell suddenly. “Would you think it odd if I told you I saw—or at least I thought I saw—a submarine—about a thousand miles back, somewhere west of the Maldives?”

Captain Baldridge swiveled around, his smile gone. “Which way was it heading?”

“North, sir, same way as I was.”

“Why do you think it was a submarine?”

“Well, I’m not certain, sir. I just happened to notice a short white scar in the water. But there was no ship, just the wake. I only guessed I was looking at the ‘feather’ of a submarine. I couldn’t really be sure.”

“Pakistani I would guess,” replied Captain Baldridge. “Probably about to swing over to Karachi. But you’re right. You don’t often see a submarine in these waters—unless it’s ours, which this one plainly wasn’t.”

“Anyway, sir. Hope you didn’t mind my mentioning it.”

“Not at all, Lieutenant. Sharp-eyed aviators have a major place in this Navy. I’m grateful to you.”

“One thing more sir…I thought it disappeared, but then about coupla minutes later, just before I overflew it, I noticed it again. I suppose it could have been a big whale.”

“Yes. Possibly. But thank you anyway, Lieutenant,” said the captain. “Before you have lunch, put a message into the ops room and give your precise position when you spotted her, will you? You say she was heading slowly due north?”

“Yessir. I’ll give them that information right away.”

291130JUN02. 11N, 68E.

Course 050. Speed 7.

“Okay, Georgy, I’d say we’ve gone far enough. If they haven’t come looking for us by now they’re not coming. Besides, our little detour took us right off the line of flight of that U.S. aircraft, if, as I suspect, it’s on its way back to Diego Garcia.”

“You want me steer left rudder course three-three-zero?”

“Three-three-zero it is.”

012000JUL02. 21N, 63E. Course 215. Speed 10.

The Thomas Jefferson.

The Thomas Jefferson headed into the wind. Standing by for the first launch of the night-flying exercises, Jack Baldridge and Zack Carson shared an informal working supper in the admiral’s stateroom.

“Well, I wouldn’t get yourself over excited, if I were you, just on account of the uncertainties,” Admiral Carson said, grinning. “First, we don’t even know it was a submarine. Second, we don’t know who it belongs to. Third, we do not know either its speed or its direction at this precise moment. Fourth, we have no idea what his intentions are. Fifth, just how much of a shit do we give? So far as I know, we aren’t even at war with anyone. At least not today. And the only Arab nation which even owns a submarine in this area is Iran, and our satellite says that all three are safely in Bandar Abbas.

“At least it did, three days ago, and you can be dead sure we’d know if they’d moved one of ’em. There are two other nations bordering this part of the Indian Ocean. They both own submarines, but are both more than friendly with the U.S.

“So unless that good-looking broad with the big eyes and tits who runs Pakistan is suddenly turning nasty on us, I don’t think we have a lot to get concerned about. Jesus, she went to Harvard, didn’t she? She’s on our side. Want another cheeseburger?”

Baldridge, laughing, “Well, Admiral, if he’s a nuke, and he’s coming our way, we’ll catch him for sure when he gets real close. The last exercise has just shown we can catch the quietest in the world. Good idea, let’s hit another one of those burgers.”

051700JUL02. 19N, 64E.

Course 045. Speed 4.

“Well, Georgy, this is just about it. Aside from our little trip to India, we are here on time. The monsoons are also on time and the weather seems excellent for our purposes. I do notbelieve we have been detected, and right now she’s around 120 miles to the north. We have tons of fuel, and if we aren’t caught going in, there’s no great likelihood they’ll get us on the way out. It’s entirely possible they won’t even realize we exist.”

“I guess you right, Ben. You always are. But I worry…why they so busy?”

“Not really, Georgy. We’re hearing just normal ops on station so far as I can tell. We just stay under five knots, dead silent, and keep edging in. Let’s check the layers, see if we can improve the sonars a bit. The weather’s getting so murky we can’t see much anyway.”

071145JUL02.

In the ops room of the old eight-thousand-ton Spruance Class destroyer USS Hayler, positioned twenty-five miles off the starboard beam of the Thomas Jefferson, Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer Lieutenant Commander Chuck Freeburg was contemplating the rough weather. In this cavern of electronics warfare, the darkened room, lit mainly by the amber lights on the consoles, was pitching and rolling with the rising sea beyond the kevlar armorplated hull. A new track appeared suddenly on his tactical screen, 5136 UNK.

Turning to the Surface Warfare Compiler, Freeburg said quickly, “Surface compiler, ASWO, what is Track 5136 based on?”

“Desk Three reported disappearing radar contact. Four sweeps. No course or speed.”

“ASWO, aye. Datum established in last known. Datum 5136. Put it on the link.”

071146JUL02. 22N, 64E. Course 035. Speed 12.

On the Admiral’s Bridge of the Thomas Jefferson.

Big seas have caused the cancellation of all fixed-wing flying. Captain Baldridge is speaking on the internal line.

“Admiral, I had this disappearing radar contact fifty miles southeast. Datum established on the last known.”

“How many’s that today, Jack?”

“That’s the fifteenth I think, Admiral. Must be the weather.”

“Well, we can’t afford to ignore them. Keep the PIM out of the ten-knot limited line of approach. Get a sonobuoy barrier down, this side of the datum. If it’s a submarine, we’ll hear him as he speeds up. If he stays slow, he’s no threat. If it’s not a submarine, who cares? Don’t wanna waste assets on seagulls.”

“Aye, sir. We always get ’em around here. I guess there may be some kinda current or upwelling causes it.”

“Still we don’t want to run scared over four sweeps on a radar scan. Let’s proceed, but keep watching. Lemme know, Jack, if something’s up.”

071430JUL02. 20N, 64E.

Course 320. Beam to sea. Speed 3.

“Shit! You see that? Jesus Christ! I just seen sonobuoy, starboard side. We nearly hit the fucker. They must have heard us. Holy Christ!

“Ben!There’s a sonobuoy right out there forty meters. They must have anti-submarine aircraft in the air. Jesus Christ! Ben, we don’t fight U.S. Battle Group, they kill us all.”

“Cool it, Georgy. Cool it. Keep the speed down to three knots, which means we are silent, and keep listening. Also try to keep that somewhat hysterical edge out of your voice. It will make everyone nervous, even me. Keep creeping forward. And for Christ’s sake cool it. Now let’s have a quick chat in your cabin….”

“You say cool it! Jesus Christ! Ben, they bring in frigates and choppers, surround us, we caught like rat in a trap. Oh fuck, Ben. Yankee bastards—they kill us, no one never know. Oh fuck.”

“Georgy, shut up! Let me remind you we have as much right to be in these waters as they have. They will do nothing to usunless they are sure we are going to do something to them. Anyway, I could pass for an Indian officer. I can speak passable Urdu, but my Anglo-Indian is certainly sufficient to confuse an American commander.

“They have no right to search this ship, and we have committed no offense against anyone. So kindly refrain from panic.”

“You are a hard man, Ben. But you forget. Americans can do anything. They trigger-happy cowboys. They call everyone to find out about us. We never get out of jail. Like that French bastard Napoleon.”

071600JUL02. 21N, 64E.

Ops Room. Thomas Jefferson.

“Yeah, I heard the Sea Hawks are back, found nothing. Which at least means there’s not some spooky nuclear boat following us around.”

“Probably means there’s nothing following us around. They got nothing on the barrier. Hardly surprising in this god-awful weather. Bet it was just a big fish. If there was an SSN snooping around we’d hear him. We’d hear him for sure.”

“We would if he was nuclear. But I don’t think Captain Baldridge is very happy. He’s been down here in the ops room three times in the past two hours, asking questions.”

072300JUL02. 20N, 64E.

Course 340. Speed 3.

Back and forth on a four-mile patrol line. “We just wait here, Georgy, and stay silent. No need to go anywhere near the sonobuoys they dropped. I think the big ship will come back to us in the next day or two.

“Right now we have time to get a good charge in. We’re just about in the middle and I doubt they’ll be looking for us here. Then we’ll be okay for two or three days, smack in the right place at roughly the right time. Crew happy? What did you tell them?”

“Just what we agreed, Ben. They still think we are on special exercise, making covert test of new nuclear weapon. I tell them Indians get the blame for breaking test ban treaty. Once it gone, maybe trouble from crew. But too late then, and they not know what happen. Even Andre, he not know, but I tell officers quick, right after. They control crew. Maybe worry for first minutes, but okay I think. No choice for them anyway.”

081758JUL02. 21N, 62E. Course 220. Speed 10.

The Thomas Jefferson.

Weather foul. Very strong monsoon gusts. On the Admiral’s Bridge, Zack Carson and Jack Baldridge were peering through the teeming bridge windows, and all they could observe was a couple of miles of murky, rainswept sea. All fixed-wing flying had been canceled for the night.

“Strange weather, Admiral. You’d kinda expect a chill when it’s so gray and wet. When it looks like this in Kansas, it’s usually as cold as a well-digger’s ass.”

“This is the southwest monsoon, Jack. It’s a warm wind blowing right across the equator, and it brings with it all the goddamned rain India is gonna get this year, from now till about next spring. Mustn’t that be a bitch if you happen to be a farmer?”

They stood in silence for a while, and the carrier was curiously quiet, with the flight deck almost deserted. Only the occasional squall slashing against the island of the carrier disturbed the peace, as the giant ship pitched heavily through the long swells, 130 feet below the two officers. They were heading back upwind, across the carrier’s 120,000-square-mile patrol zone.

If he squinted his eyes, Zack could just make-believe he was looking at a great field of Greeley County wheat in the gray half-light of a rainy summer evening. He’d hardly ever been in hilly country in all of his life. His landscapes were strictly flat, the High Plains and the High Seas. He thought about his dad, old Jethro Carson, still going strong at eighty years of age, ten years widowed now, but still the master of those hundreds and hundreds of acres. And Zack resolved to take the entire family out to visit in the fall, when the warm, sweeping grasslands of his youth were, to him, so unbearably beautiful.

“You don’t think there really is anything out there snooping on us, do ya, Jack?”

“No, Admiral, I really don’t. But when you get a contact, you gotta run the checks. It’s not my job to take anything at all for granted. Especially with those sneaky pricks. But I do believe if some goddamned foreigner was sniffing around our zone, we’da got him by now.”

“I guess so, Jack. But those Russian diesels were just about silent under five knots.”

“Yeah, but they weren’t that good. And even in this weather we’d be sure to hear them snorkeling.”

081800JUL02. 20N, 64E.

Course 155. Speed 3.

“She’s out there, Georgy, off our port bow, coming back from the northeast.”

“I guess three to four hours. You sure about this, Ben?”

“I am sure, my nation is sure, and my God is sure. I expect your bank manager would also be sure.”

“I want distance five thousand meters—not closer. This thing very stupid, very big. Work on time only. Run four minutes. We might get a more accurate distance visually. But we might not.”

“Check all systems, Georgy. For the last time. We’ve come a long way for this. I just wish we could have done it four days ago. More poetic somehow.”

082103JUL02.

On board the nine-thousand-ton Ticonderoga Class guided-missile cruiser Port Royal, operating close in to the carrier, Chief Petty Officer Sam Howlett decided to take a breather. As he stepped out onto the portside deck the murky sky suddenly lit up. A deafening blast followed seconds later. As Howlett instinctively grabbed for the rails, a thunderous rush of air took him by surprise, flinging him sideways and downward, his skull fracturing as he hit the deck. Before losing consciousness, Howlett looked up to see the towering SQ28 Combat Data Systems mast rip clean out of its moorings and crash onto the deck. The great warship heeled to starboard and the giant mast rolled with it, crushing a young officer on the upper deck outside the bridge.

Astern, on the flight deck, the blast flung the LAMPS helicopter off its moorings onto the missile deck, killing two flight deck crew. Its ruptured rotor, spinning in the rush of air, snapped in two, decapitating a twenty-three-year-old aircraft mechanic. Two other men were blasted one hundred yards out into the sea.

Below, the force of the smaller for’ard radar mast slamming into the port edge of the deck split it in two. As it caved in, the deck crashed into a fire main, rupturing it. The split fire main crashed down into a companionway, trapping two sailors while it pumped out hundreds of gallons of compressed seawater, drowning them both. A twenty-year veteran Petty Officer, with blood streaming down his face and three broken ribs, wept with rage and frustration as he tried unsuccessfully to free them.

Up on the bridge there was carnage. The top of the main mast had broken off completely, and it plummeted down, smashing through the roof of the bridge and killing the Executive Officer, Commander Ted Farrer. Every portside window shattered in the blast, one of them practically severing the right arm of the young navigator, Lieutenant Rich Pitman. The face of the Watch Officer was a mask of blood. Young Ensign Ray Cooper, just married, lay dead in the corner. The cries and whispers of the terribly wounded sailors would haunt Captain John Schmeikel for the rest of his life.

The suddenness of the disaster from nowhere temporarily paralyzed the Port Royal. No one knew whether they were under attack or not. Captain Schmeikel ordered the ship to battle stations. All working guns and missile operators sought vainly for the unseen enemy, a task rendered impossible with no radar, no communications, no contact with any other surface ship in the Battle Group.

082103JUL02.

On board the eight-thousand-ton Spruance Class destroyer O’Bannon, also working close in to the carrier, no one had time to move. The blast of air roared through the ship, heeling her over almost to the point of broaching, hurling sailors into the bulkheads. But it was the following near-tidal wave which did the damage. The ship had not quite righted herself when the mountain of water hit the O’Bannon amidships. This time she almost capsized, and down in the galley, where cooking oil was now streaming across the floor, a terrible fire swept from end to end. Two oil drums exploded, and all three of the duty cooks were shockingly burned in the ceiling-high flames—twenty-four-year-old Alan Brennan would later die from his injuries, and his assistant, nineteen-year-old Brad Kershaw, lost the sight of both eyes.

Eight men were catapulted overboard when the wave struck. Three of them were hammered into the bulkhead and were unconscious when they hit the water. These men would never regain consciousness, despite swift and heroic rescue attempts by the crew.

The engine room was a catastrophe. Chief Petty Officer Jed Mangone suffered terrible facial burns in a flash from an electrical breaker, and two young engineers were crushed by a huge generator they had been repairing. Neither of them would ever walk again. Up on the bridge the scene was almost identical to that on the Port Royal. Flying glass from the blown windows had reduced the area to a war zone, a grotesque scarlet and crystal nightmare, in which no one had escaped injury.

Captain Bill Simmonds, who would later need sixty-three stitches in his face, took over the blood-soaked helm himself, ordered his ship to battle stations, cursed the communications failure, and roared at the top of his lungs for someone to access the Flag.

082103JUL02. 20N, 64E.

Course 230. Speed 25.

Twenty-four miles northeast of the carrier, the USS Arkansas was changing course, closing to her former position in the inner zone, as decreed by the admiral’s policy of frequently altering the disposition of his group to hide the carrier on any foreign radar screens.

“Captain…Conn. Just saw a weird flash in the murk to the south. Coulda been lightning, but it don’t seem right somehow.”

“Captain, aye. Coming to the bridge.”

“Conn…CIC. Sonar reports massive underwater explosion. Bearing two-four-five…”

“Captain, sir, sonar reported massive underwater explosion…two-four-five…I’m turning toward.”

“Got that. What’s going on?” But even as he spoke, a thunderous explosion split the night, and a blast wave of solid air crashed through the bridge windows.

The rest was lost in the roar of the wind and the unexpected chaos on the bridge, as the Watch Officer tried to restore order in the dangerous shambles of broken glass and wounded sailors.

And now behind the first blast, another wind was rising, a grotesque unnatural wind, warm and vicious, like the height of a typhoon, sweeping across the ocean, blasting now across the upper works and radar installations of the big Aegis missile cruiser, slowing the eleven-thousand-ton bulk of the warship in her tracks.

“Jesus! What’s going on out here? Is this an earthquake?”

“Captain, sir. That was one hell of a blast—Jeez! You feel the ship stagger? And why has the wind backed a whole twenty degrees? Even the sea feels strange, rolling in from the wrong angle.”

“Beats the hell out of me…but it has to be one hell of a disturbance. I think we will…wait a minute…” To himself, “Take no chances, Art.” Then “Okay…Go to General Quarters, Officer of the Deck.”

The captain stayed on the bridge, but down in the sonar room they were replaying their record of the apparent subsurface eruption which had occurred several miles away just moments before. At least they did not hear the dreaded noise of tinkling glass that always echoes and echoes, back through the underwater, and then through the mind, when a big ship goes down. Instead there was just a strange continued rumbling, slowly dying away to eerie silence. No one had any answers. None whatsoever.

Whatever had caused the violently freakish conditions had also caused a certain amount of chaos in the operations center of the USS Arkansas. Communications were down everywhere. The big round radar screen that showed the surface picture of the Battle Group was out altogether, and the Air Warfare Officer was trying to coax it into life. It seemed darker than usual because so many screens were blank.

Captain Barry headed for his high chair and hit the UHF radio phone on the inter-ship network, direct to the carrier’s Combat Information Center. The line was a dead end. No one in the command ship replied. But he heard an erratic transmission voice from one of the outlying frigates, almost seventy miles away to the south, apparently calling the carrier. “Jefferson…this is Kauffman…Radio check…Over.” But faraway Kauffman was getting no answer either. Art Barry tried the encrypted line to the admiral’s ops room. No reply.

Then he tried the direct line to his baseball pal, Jack Baldridge. There was total silence on his phone too. Captain Barry asked Comms for a satellite link to the carrier…“Sir, we’re having a real problem with satcom…aerial stabilization, intermittent malfunction. Been trying for several minutes…achieved occasional access to the satellite, but there’s no contact from Jefferson. As far as I can tell all normal comms with the Flag have died on us.”

“Someone try to raise the CIC in the O’Kane. She’s operating close in today, a couple of miles off the carrier’s port bow. They’ll know more than we do….”

“No communication there either, sir, we were just trying.”

“Okay, try Hayler, she was about twenty miles out when we lost the surface picture. Get their captain…yes, regular UHF.”

“They’re on, sir! Commander Freeburg, encrypted.”

“Hey, Chuck…Art Barry. Can you tell me what the hell’s going on around here…we can’t raise the carrier, most of my comms are down, and we couldn’t raise O’Kane either…neither could you…? Jesus…! Who?…You got one of the SSN’s in comms? It was a big bang all right…God knows…! You’re heading in to meet the carrier? No…don’t do that. Hold station on formation course and speed. I am approaching Jefferson’s last known to investigate…Meantime, I’ve gone to GQ and I’m gonna turn on my radiation monitors…you better do the same. There’s something weird goin’ on here…I will keep you informed.”

“Captain, sir, look out. The biggest wave I’ve ever seen is coming…!”

As the Watch Officer shouted, almost in slow motion, a sixty-foot-high wall of ocean seemed to rise up from nowhere. It hit the Arkansas head-on, breaking right across the fo’c’sle, and up over the superstructure—thousands of tons of green water crashing across the guns and missile launchers, submerging the entire ship it seemed, and roaring through the broken bridge windows.

But like all modern warships, she righted herself swiftly, seeming to shake the ocean from her decks, and shouldered her way forward with seawater still cascading down the hull. The Officer of the Watch could see the colossal wave rolling on, like that strange wind, toward the northwest and the shores of Arabia.

The next wave was not quite so big, but it swamped the ship again, and the one after that did the same. Slowly the waves diminished, and as the seas returned to the normal swell, the Officer of the Watch set about checking that no one had been swept or blown overboard.

Twenty-six minutes had now passed since the weird flash in the southern sky had barely been sufficient for the Officer of the Deck to bother his captain. But now only four of the possible ten other Battle Group surface warships were coming up in comms with Arkansas. Art Barry found himself apparently in charge of the group until the carrier came back on line. He established that both guided missile frigates, the four-thousand-tonners Ingraham and Kauffman, appeared intact, as did the four-thousand-ton Spruance Class DDG Fife. The other Spruance, Hayler, appeared in similar shape to the Arkansas, wind-and sea-swept, but almost back to full working order.

Both SSN’s, Batfish and L. Mendel Rivers, reported themselves unharmed at periscope depth. Both submarine captains gave their intentions, to remain on original station fifty miles out from the carrier, west and east respectively, on formation course and speed, maintaining constant comms. “Outfield beautiful,” muttered Barry. “Where the fuck’s the pitcher?”

Everyone in comms was now reporting the same violent underwater upheaval. Ingraham and Kauffman were first hit by a smaller forty-foot wave. Both of them were fifty miles out from ZULU ZULU (the Group Center) at the time. Hayler and Fife, however, had been about twenty-five miles out, and like Arkansas, had taken a sixty-foot wave. Unlike Arkansas, Ingraham had taken it right on the beam and very nearly capsized.

Of the missing six ships, not yet in comms, there appeared to be only five surface radar contacts close to ZULU ZULU. These were all stationary, or nearly so. By 2145 Arkansas’s surface picture was back in business, which partly clarified the situation for Captain Barry.

He could now see twelve other contacts from his ink picture, including himself. There were two SSN’s and five surface warships in good to reasonable shape, five others were floating, but unidentified, and still making way to the southwest, but out of comms.

One was missing.

At 2150, the ship’s broadcast of the Arkansas blared: “Radiation alarm! Radiation alarm! Clear the upper deck. Assume condition 1A. Activate pre-wetting. Decontamination parties close-up.” This official imperative ended with the traditional U.S. Navy roar of no-questions-asked, do-it-now urgency…“No shit!”

Within seconds all ventilation fans were crash-stopped. It took ten more minutes to get the ship properly isolated from the outside air, from the radioactive particles, which had set off the monitors. She was now like a huge, sealed cookie tin.

Every hatch, every flap, every external bulkhead door, every opening to the outside air was clipped hard home. Only then was it safe to bring in the gas-tight “citadel” ventilation to provide fresh air via special filters which would sift out all the radioactive particles. The system raised the pressure inside the citadel to slightly above atmospheric, and thus prevented any inward leakage of the lethal radioactive outside air. All drafts were headed OUT.

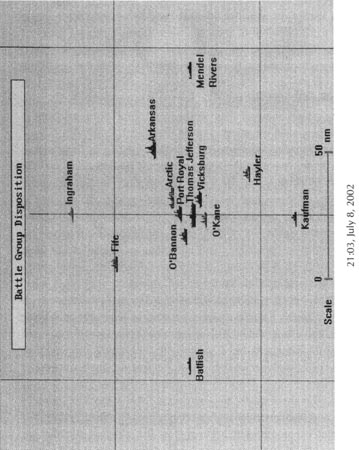

Radar picture from the Thomas Jefferson showing its position within the Carrier Battle Group, July 8, 2002

As the ship swung away across the monsoon wind, and cleared the radioactive plume to the north, the upper-deck working parties began to power hose the decks with saltwater and bleach, standard procedure for clearing radioactive particles from every area in the path of a nuclear explosion. Monitoring parties accompanied the hose crews, checking every corner.

By 2155, Captain Barry was ready to take a break. He needed thinking space to assess what had happened. There had plainly been a nuclear detonation, and he desperately needed to find out which ship was missing. Six would not, or could not, answer, and only five were on his radar.

For a couple of minutes he stared at the screen, willing it to produce the sixth contact at the center of the group. But his space-age electronics were unable to tell him what he needed to know: who was missing?

He knew he would have to go back to basics, to what sailors call the “Mark I Eyeball.” He ordered a course change: “Conn…Captain…come left, two-three-five…flank speed…I am closing to make visual contact on the most northeast contact of the group ahead…that is track 6031…he may have no lights burning…check visual signaling lamps.”

By 2309, Captain Barry had seen what he needed to see with his own eyes, searching the dim, shadowy seas, probing the darkness to come alongside each of the four ships that showed up on his radar.

He was able to identify the huge 49,000-ton full-load fleet oiler Arctic, minor casualties only, radar and comms out, but 70 percent operational. He found the formidable 9,000-ton Ticonderoga Class guided-missile cruiser Port Royal, with ten dead, twenty injured, severe aerial damage, major structural damage in the stern area, including her harpoon battery and one helo, severe flooding in the hangar area.

He also found her sister ship, USS Vicksburg, which had taken the big wave fine on her starboard bow, no serious casualties, severe aerial damage, no significant structural damage. The O’Kane, as she lay stopped and listing in the water, was a floating wreck, in desperate need of aid. And he found the Spruance Class DD, sister ship to Hayler, the O’Bannon, many casualties, number not yet known, ship nearly capsized in the tidal wave, able to make way through the water but little else, severe damage topside and internal.

Captain Barry stared at his screen again, in shock, at the space where the carrier must have been. The radar made its familiar, emotionless, circular sweep. And still there was nothing where once the mighty warship had been. No one could see her. No one could speak to her. And no one could hear her. The Thomas Jefferson was gone.

As the senior officer in charge of the second most important warship in the Group, Captain Barry now ordered his communications office to access the satellite’s direct line to the U.S. Navy headquarters in Pearl Harbor, to Admiral Gene Sadowski, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC).

The two men spoke for less than three minutes. The sentences were terse, two lifelong Naval officers communicating in the economical language of their trade. Within moments Admiral Sadowski had opened his private line to the Pentagon. It was 1318 local in Washington, D.C., as the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Scott F. Dunsmore, picked up his telephone.

“I regret to inform you, sir,” said Admiral Sadowski, “that the carrier Thomas Jefferson has been lost in what looks like a nuclear accident. All six thousand men on board appear to have perished.”