0930 Thursday, July 18.

IT TOOK ADMIRAL BERGSTROM NINETY MINUTES TO establish his initial plan of action, in the SEAL compound, surrounded by barbed wire, behind the Coronado beach.

The admiral had ordered all of the commanders involved to enter “brainstorm mode”—and he had already presided over the short-list selection of the hit squad which would strike against the Ayatollah’s underwater Navy.

There are 225 men on each SEAL team, of whom only 160 are active members of the attack platoons. There are 25 people in support and logistics, technicians and electronic experts, with 40 more involved in training, command, and control. Each SEAL strike squadron requires enormous backup.

The senior commanders had recommended this job for the Number Three Team. They had then selected one of the ten platoons of sixteen SEALS, which made up the team. They would then choose the final squad, of probably eight, which would make the “takeout” deep inside the port of Bandar Abbas. Their leader would be Lieutenant Commander Russell Bennett, a thirty-four-year-old veteran of the Gulf War, graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, leading classman in the SEALS murderous indoctrination course, BUD/S, known colloquially as “The Grinder,” and son of a Maine lobsterman.

Bennett was medium height, with thick, wide shoulders, dark blue eyes, and a generous but well-trimmed mustache. He had forearms and wrists which might have been made of blue-twisted steel. He was an expert on explosives, a superb marksman, and lethal with a knife, especially in the water. He could scale the smoothest steel plates of any ship. He could swim anywhere in the coldest seas, and he could climb anything. Any enemy who ran into him was probably looking at the last five seconds of his life.

His subordinates worshiped him and called him “Rusty” because of his short-clipped red hair. Like most SEALS he ignored all forms of correct uniform, and went into action with a head bandage instead of a hat, calling it his “drive-on rag.” His colleagues swore he pinned his coveted SEAL golden Trident badge on his pajamas each night at Coronado. He had never gone into combat without that badge, carefully blacking it up before leaving, even more carefully burnishing it bright on his safe return. Lieutenant Bennett was typical of the kind of Navy SEAL SPECWARCOM considered adequate for platoon command.

He had twice done a stint as a BUD/S instructor, pounding tirelessly along the burning Pacific beaches at the head of his class, driving them up the sand dunes, and then down into the freezing sea, driving them until they thought they would die of exhaustion. Then driving them some more. Using the time-honored SEAL punishments, he sent shattered but still defiant men just one more time through the underwater “tunnel,” then made them roll on the beach and complete a course of grueling exercises under the agonizing grazing of the clinging wet sand.

Twelve years previously, other instructors had done it to him, driven him until he thought he had nothing more to give. But he did. And they made him find it. They forced him ever onward, through the assault courses, through the brutal training of “Hell Week,” which breaks 50 percent of all entrants, until at the end, he believed in his soul that no one on this planet could ever hurt him. At least not worse than he had already been hurt.

When he was selected as leading classman, and, in his full-dress uniform, chimed the great silver bell at the end of the course, Rusty Bennett was the proudest man in the United States Navy. And still, in the high summer of 2002, he was as hard-trained and impervious to pain as any human being could ever be.

Rusty’s father, who still set his lobster traps in the deep, ice-cold waters of the rocky Maine coast, south of Mount Desert, had long assumed that his unmarried eldest was crazy.

And now Rusty was in “brainstorm mode,” in the operations room, staring at the chart. This was the initial session involving SEALS high command and the team leader. They were dealing with absolute basics. Which submarine? Where is it? How long to get to Diego Garcia? Admiral Carter of the Fifth Fleet would have theater command, once they move into the area.

Rusty too was asking elementary questions: Strength of the current? Tide and depth? Conditions on the bottom? Guards? Patrol boats? Searchlights? Possible alarms? Likely weather conditions? Phase of the moon? Underwater visibility? How many SEALS do we need to go in? Not until these basic matters were clarified would he call in his second-in-command, who would drive in the SDV.

He made a drawing of the two Iranian Kilos in their precise positions, as provided by the satellite photographs. He sketched in the big floating dock, in the position it was last seen. He marked the place where they would leave the SSN. Marked another spot where the SDV would wait, in the outer reaches beyond the harbor, once they were all in the water.

He conferred with the weapons officers and the explosives experts, formulating the precise charge necessary for the “sticky” mine they would carry in and then clamp to the underside of each Kilo’s hull. The explosion would drive upward, through the casing, through the hull, right under the gigantic battery.

The charge had to be powerful enough to blow a big hole in the pressure hull, and ignite a major internal fire. The overall game plan was that the blast, the intense heat and searing flames, would immediately overcome the crew, while the onrushing flood of seawater would sink the submarine.

Another “sticky” mine, blasting upward, under the stern, and bending the propeller shaft, would make double-sure the Kilo never left the harbor again.

It was understood that it would take two SEALS to destroy each of the two floating Iranian submarines. The third one, the one which could be inside the floating dock, would undoubtedly prove a bit more difficult. But it had to go. After all, it might be the very one which had hit the Jefferson.

Everyone realized the floating dock might be empty, which would at least confirm they had definitely hit the right nation. But now they had to make their plans and behave as if it was going to be there—even though this submarine would be four times more tricky to take out than the others. The commanding officers knew they faced the age-old problem of big business—they were about to spend 80 percent of their effort on 33 percent of the problem—and all of that 80 percent might be wasted if the third Kilo was not there.

The action required on the first two was relatively straightforward by SEAL standards. The one in the dock involved a lot of educated guesswork, but the principle of standing up a 2,356-ton submarine in a dry dock was universal. The huge ballast tanks under the dock were flooded, on the same principle as the submarine itself, and the dock routinely sank sufficiently for the boat to be floated in.

She entered right down the middle of the dock, above a series of huge wooden blocks arranged precisely to accommodate the shape of the submarine’s keel, and spread the load of her colossal weight. The ballast tanks under the dock were then pumped out until the dock rose a few feet, and the submarine nearly settled.

Mooring wires, controlled by powerful dockside winches, were then used to position the boat in exactly the right spot over the keel blocks, accurate to the nearest inch. Eight giant wooden “shores”—around eighteen inches square, twice the thickness of a telegraph pole, and probably thirty feet long—were set against the hull, a fraction over halfway up, four on either side.

These great beams, easily strong enough to bear the weight of several men, were wedged into place with sledgehammers, to prevent the submarine from toppling over sideways.

At this point operators would start to pump out the ballast tanks, and the massive edifice would begin to float upward, very slowly, not much faster than the outgoing tide. With the dock on the surface, the submarine stood high and dry, ready for the engineers and ship wrights to begin work. It was one of the more time-consuming, difficult procedures in any dockyard. If a submarine went into dry dock it had a major problem, involving repairs below the waterline.

The floating dock in Bandar Abbas had a roof built right across the top, turning it into something the size of an aircraft hangar, anchored to the harbor bottom by monstrous steel and concrete moorings. It was not going to wreck anyone’s life in the Pentagon if the SEALS wiped that out too. But that would depend on how much “kit” the SEAL swimmers could carry.

Admiral Bergstrom, himself a SEAL veteran, made a key recommendation here. “I don’t think we need ‘blow’ the third Kilo at all,” he said. “If we could somehow smash all four shores on her starboard side, she’d crash down on her own, probably take out the entire wing wall of the dock, and possibly drive her way straight through the floor. Two and a half thousand tons is a pretty good weight to drop—it would certainly smash the dock to pieces, and put the whole lot on the bottom of the harbor with very little explosive effort on our part.”

“Yes,” replied Commander Ray Banford, “but those things are damn finely balanced. She may not fall immediately, and the noise we make blowing the shores might just alert them, maybe give ’em time to bang in another shore if they happen to have a few spares around. Just one could stop her falling.”

“She’d go if I blew a damn great hole in her starboard holding tank at precisely the same time we took out the shores,” said Lieutenant Bennett. “I guess the slightest tilt of that dock would do it. And that big float tank, full of seawater, would tilt her over half a degree in about one minute flat. She’d go then.”

“Yes, I guess she would,” said Commander Banford. “Actually I think our real problem here is the amount of guys we might need to get those shores out.”

“One man on each,” said Rusty. “That’s four. I’ll go in first, under the dock, and attach some kind of a mine to the tank. Then I’ll stand guard while the guys wire up the shores. We’ll use det-cord. We’ll hook up the explosives to the same detonator, give ourselves time to get clear, and the whole lot will blow together. She’ll go. No doubt, she’ll go.”

“Right here, we’re talking a lot of guys,” said Banford, the exsubmarine commander, who would oversee the mission. “We need four men for the floating Kilos. Four for the shores. Couldn’t two guys do two each?”

“Too dangerous, sir. Don’t forget we’ll be working close to the guard on the deck of the submarine, but just out of his sight-range. If he hears one sound he’ll start looking, then I’ll have to take him out, then someone else might hear, then we’ll end up taking a dozen of ’em out, with all hell breaking loose.

“No, sir. I think we should move at twice the speed, with four men, one on each shore working simultaneously.”

“Yes, Rusty. I do see that, it’s just the number I’m worried about. Four men on the two floating Kilos, four men on the shores, you blowing the float tank and standing guard—that’s nine, plus the driver of the SDV. That’s ten, and the SDV only holds eight.”

Admiral Bergstrom spoke next. “Well, Ray, we do have a new Swimmer Delivery Vehicle, delivered in the past few weeks. It does hold ten. They call this one an ASDS, an Advanced Swimmer Delivery System, electric-powered, made by Westinghouse. It has a longer range than the old Mark VIII, probably twelve hours, and it does hold ten guys.

“If you assume three hours to get in and three hours back, plus four hours waiting, that’s ten hours, if nothing goes wrong. She only makes five knots, but she’s nearly perfect for us. Trouble is, I don’t know whether she’s operational yet. And I believe we only have two SSN’s fitted to carry her…. Tommy!” He beckoned over to Lieutenant Tommy Schwab, asked him to check out the submarine situation with SUB-PAC, Vice Admiral Johnny Barry, Commander, Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet.

Meanwhile they agreed in principle to a ten-man team. And Lieutenant Rusty Bennett then threw another curve ball. “I think we should blow the boat in the dry dock at the earliest possible time,” he said. “It is likely they will have a sentry patrolling the walkway around the top of the floating dock. If we leave that det-cord in place for one and a half hours while we get away, he’s got a good chance of spotting it if he’s sharp. He only has to notice it on one of the shores and they’ll find the whole detonation network and cut it.

“I think we should set the det-cord to blow ten minutes after we hit the water. We’ll be a few hundred yards away by then, and we’re not talking huge underwater explosion, just the minor blast on the float tank. That won’t affect our eardrums. The rest of the explosives are high up in the dock, and the damage is going to be slow motion, zero-blast underwater, all in the same place.

“If we just let the submarine crash through the dock, they won’t even suspect they were hit by anything military. And there will still be chaos in the base when the other two Kilos blow. We can set them to go two hours after we leave, by which time we’ll be back in the SDV and well on our way across the bay. I’m figuring they’ll want an hour to get their act together and come after us with a patrol boat. We’ll be in the SSN before they get a sniff.”

“Good thinking,” said the admiral. “It sure would be goddamned irritating if we set the whole thing up and then they found the det-cord before we blew out the shores.

“One question…have you guys thought yet how you’re going to work up high, on the side of the submarine? I mean A, how are you going to get up there? B, how will you avoid being seen? And C, what protection do you have?”

One of the senior instructors, a Chief Petty Officer, stepped forward. “According to these drawings we have here, the shores will be positioned about thirty feet from the floor of the dock,” he told the group.

“Well, we can’t climb the curved sides of the submarine, nor can we risk going up onto the walkway around the top of the dock. So we have to go straight up a rope to each shore. We’ll use fairly thick black nylon, with a big foothold knot every two feet, and a small, padded black steel grappler on the end. The guys will twirl and throw the grapplers from the floor, up and over the beams. When the hook grabs and digs into the wood, they go, straight up, and straddle the beams.

“They’ll work close in, maybe five or six feet from the hull of the submarine. That way the sentry cannot see them without crawling right down over the edge, in which case he’ll fall off. Most likely he will be in a chair, possibly asleep, right in the middle of the deck, under the bridge, looking aft.

“Most of these big floating docks have steel ladders at the ends and one about halfway along the wall which goes from the floor up to the walkway. Rusty will position himself as far up there as he needs to be, just enough to train his sights on the sentry’s head. Rusty’s gun will of course be silenced.

“The guys will wind the det-cord around the beams probably about six times, that means they will each want about forty feet of the stuff up there, with another forty feet hanging down and another eighty feet to connect to the next beam. Our stuff is dark green in color, and det-cord’s not too heavy. It’s thin, and we can wrap it tight. It’ll be awkward swimming in, but we’ve done much worse.

“I estimate the guys will be up on the wooden beams for no more than four minutes. Rusty can make the joins, and fix the detonator and timing mechanism as soon as he gets down the ladder. He says ten minutes, maximum.”

“Thank you, Chief,” said the admiral. “You starting practice today?”

“Nossir, I’m fixing up for us to use AFDM-14, the big floating dock right here in San Diego. They have a submarine in it right now, on shores. I thought we’d spend two days over there, by which time this team will be world experts with a thirty-foot throw with rope and grappler.

“Most of them have done it before, sir, but we must eliminate every possibility of a mistake. What we don’t want is for one of those ropes to fail to fetch the beam, because then the damned grappler will fall and thump on the steel floor of the dock, and then Rusty may have to kill the goddamned sentry.”

“Guess so, Chief…”

Just then the door flew open and Lieutenant Tommy Schwab rushed in. “Sir,” he said, “we just got lucky. Real lucky. The SSN we want is one of those old Sturgeon Class boats, L. Mendel Rivers. She’s recently been converted to take the new ASDS. She was one of the two SSN’s with the Thomas Jefferson, and she’s in Diego Garcia right now.”

“Perfect,” said the admiral. “What about the ASDS?”

“Yessir. She’s about ready for ops, but she’s still right here in San Diego. So we’ll have to fly her out in a C5A with the SEAL team. But the Mendel Rivers is ready and waiting, being serviced right now. We’re all set.”

“Now that’s great,” replied Admiral Bergstrom. And turning to the Chief Petty Officer in charge of training, he said, “We can get the SEALS familiarized with the new vehicle right away. When do you reckon they’ll be ready to go?”

“Well, we have swimming and weight tests, plus the rope training. Weapons testing. A couple days’ instruction on operating ASDS. Plus a day coordinating everything. They’ll be ready to fly out next Thursday night on the regular Navy flight out to DG, you know, the old C5A Galaxy right out of San Diego.”

“Well done, Chief. Couldn’t be better…oh, Tommy, call CNO’s office and make sure he’s told about all this, will you? Top secret. He’s waiting.”

“Aye, sir. Thursday night flight, right?”

At this point the broad plan for the mission was formally approved by Commander Banford. Rusty Bennett routinely informed his men they were now, officially, in isolation. Phone calls were banned, even to wives and children. No letters could be written, not even postcards. No faxes, no fraternizing with anyone not involved with the planning and training. In that way, there was no chance of anyone, however unintentionally, compromising the mission.

The men were permitted to update or write their wills, and these would be held in the SEAL archives until their safe return. Or failing that, they would be pronounced legal by the Navy.

Rusty Bennett spent the first evening in conference with his whole team, thinking it through, measuring accurately on the charts all of the distances. In particular the navigational plan for the ASDS—from the Mendel Rivers to its waiting position outside the port of Bandar Abbas. His second-in-command, referred to as 2IC, a lieutenant junior grade, David Mills from Massachusetts, sat in on these meetings, since he would drive the miniature submarine in while Rusty navigated. The other eight men would sit behind them, in the dry but cold air, breathing through tubes connected to a central air system in the ASDS, as it crawled slowly and silently through the ocean, fifteen feet below the surface.

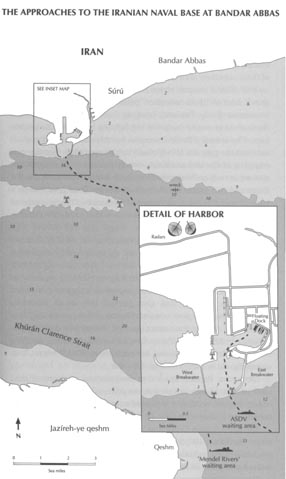

The sea miles were plotted with immense care. Rusty Bennett himself called out the information…“Total distance SSN to ASDS waiting position at 56.12E, 27.07N…is 12.93 miles…course three-three-eight…two hours and thirty-five minutes at five knots…add thirty minutes for the launch…at ten and a half miles there’s a red flashing light every seven seconds marking a long shoal to port…water’s only about twenty feet deep in there…if we see the light we’re plenty close…it should be about 750 yards off our port beam as we pass…we don’t want to be way off course on the right either, because there’s a wreck marked there—in about thirty feet of water very near the inward channel.”

Rusty Bennett was in fact never off course, having been brought up in his father’s lobster boat, creeping his way through the fog that often blankets those enchanted pine-tree islands off the Maine coast. Rusty Bennett was reading ocean charts when most kids were still busy with Mr. Rogers. His father was a native of the outward island of Monhegan, and his mother’s maiden name was Lunt, the famous Down East family that ran the boatyard and lobster fleet out of Lunt Harbor, Frenchborough.

The sea was in this particular SEAL’s blood for generations. And he came from a cold, dangerous northern sea, in which the big marker buoys, with their chiming navigation bells and flashing lights, were often the only means of avoiding a catastrophic loss of bearing and direction. Miss one of them in bad weather, and death might be staring you in the face. Unsurprisingly, Rusty Bennett was one of the best navigators the SEALS had ever had.

Every time he spoke, someone took down his words. By the time he turned his attention to the Iranian submarine base, there were two note-takers, one Senior Petty Officer double-checking every figure, and another following Rusty’s progress on a second chart…checking, checking, checking. Another man on the computer keyboard was entering the navigation plan in a file now marked “Operation Vengeance.”

Rusty Bennett kept talking. “Probable distance from ASDS anchorage to right-side harbor wall…five hundred yards…bearing two-eight-four…there’s a green navigation light on that wall…we may even see it. Right there we turn right…bearing zero-zero…heading for the inner harbor…thirteen hundred yards…this wants counting carefully…because we make a right there…that’s two hundred yards beyond a second green light…this one flashing quickly…water’s only about nine feet deep in here close to the wall…after that second right turn we swim for a thousand yards on a nine-zero bearing…right there we should be outside the floating dock…five of us bail out there and get up on it…possible four-or five-foot climb….

“The other four keep going on bearing…the Kilos berthed either side of the jetty will come up inside 50 yards…total swim distance in is thus 2,800 yards…it’s gonna take us one hour to swim that, then we’ve got 160 yards further to go…allowing for nav stops…say ten minutes…that’s seventy minutes from exit ASDS to the dock.”

They finally wrapped it up just before 2300, and headed thankfully to bed. The chief who ran the training program wanted all five of the dock team ready to leave for the San Diego base by 0630 the following morning. Rusty mentioned that since he wasn’t throwing the grapplers over the shores, maybe he was unnecessary. The chief’s reply was curt. “What if someone gets hurt, and you’re not sure about getting the grappler over, first time, sir?”

“Yes, guess so. But who would cover the guys then?”

“That’s SOP, sir. Either your wounded man can get up the ladder to do it, or you shoot the fucking Iranian guard, nice and quiet, before you start.”

“Oh yeah, right, Chief.”

Shortly before 0700 the next morning, the Navy jeep drove onto the jetty alongside the huge floating dry dock, Steadfast, positioned deep inside the San Diego base. Six men jumped out of the vehicle, and immediately the chief began to speak. “Now, you can all see the size of it, right? The wing walls are 83 feet high, and close to 260 feet long. I should think the one in Bandar Abbas is nearly identical, because a Russian Kilo is 242 feet long.

“See those two cranes high up, on top of the wall? Well, they can lift thirty tons and you find them on top of all floating docks. Also up there you are going to see a control tower, and in there you may see a guard and an operator, or just an operator who doubles as a guard. In front of him are the hydrovalves and flooding systems, and he has a set of illuminated dials which show him the angles of the dock in the water.

“They are really just like spirit levels. Theoretically, when Rusty blows a hole in the starboard-side ballast tank, the dock will begin to tilt. What we don’t want is for the guy in the tower to notice something very early and then compensate for the list on the dock by flooding the opposite tank as well. But I don’t think he will have time. A little later, we’ll give that a bit more thought, and then we’ll go up and act out the scenario a few times ourselves, just to see what might happen and to get accurate times.

“Meantime, let’s get into the dock, and see how good we are at hurling the grappler ropes up and over the shores.”

All five men took their rope coils out of the jeep and headed for the engineer’s platform which was moored on the stern of Steadfast. They crossed from the jetty, and walked into the floating dock, all of them for the first time. From water level it looked massive, and so did the submarine propped up inside. They stood alongside the boat, and above their heads they could see the big wooden shores, four of them in a line, about thirty feet above the steel deck.

The trainer told them the secret of standing at least twenty feet in front of the unseen perpendicular line from the beam down to the floor. “That way, you pick your angle, and throw the rope up, underarm, in a dead straight line, making sure it goes above the beam. That way when it drops, it must come down on the far side, and then you just pull, and the grappler will come up and dig into the wood. You want to give it a good jolt, but nothing too loud.

“The trick is to learn to twirl the hook in a large circle, clockwise as you look at your right hand. You need to know exactly when to let go. That’s just practice. Okay, Lieutenant Commander, show ’em how it’s done….”

Rusty got into position, and began to whirl the hook around until the noise made a hum in the air. He gazed upward and let go. Too low. The grappler flew twenty feet above the ground like a rocket at least ten feet below the beam and crashed down onto the deck with an unnerving, echoing thump and clatter.

“Well, sir, I’d say you just came up with a pretty good way of getting all five of you killed right there,” said the chief. “I said you needed practice and that’s what you’re gonna get.”

One by one the SEALS aimed their hooks up and over the beam; only one made it the first time, but he missed the next time. Seven hours later they were still there, and the standard was now almost flawless.

“In the end, it’s like riding a bike,” said the chief. “Once you know how, you never forget. I’m getting pleased with you, but I shall want each of you gentlemen to throw six perfect passes over the beam, one after the other. Anyone misses, you all start again, until we get thirty passes all sailing over. No mistakes.”

“You ever consider becoming a basketball coach?” asked one of the SEALS.

“Sure I did, but only for the money. I wouldn’t have saved so many lives…missed…the way you’ve been missing since this morning…too low…because you’re letting go a fraction of a second too soon…now come on, get yourself centered…three twirls…rock steady rhythm…then let go…one!…two!…three!…Release!…You got it…straight over…stay centered…five more times…”

In Fort Meade, Admiral Morgan was still pursuing the Black Sea theory and had received a report from Admiral Sadowski in Pearl Harbor. It had been filed originally in Diego Garcia by a Navy pilot, Lieutenant Joe Farrell. The lieutenant wished to bring to the attention of any inquiry that he had spotted what he thought was the “feather” of a submarine at 1130 on June 28, one thousand miles due south of the Battle Group.

The white trail in the water had been clear to him, as had the total absence of any ship. Lieutenant Farrell had landed on the carrier and reported his sighting immediately to Captain Baldridge. At the specific request of the Group Operations Officer he had then made an official report to the ops room stating the time and position of the suspected submarine.

Unfortunately, there was nothing of this left, but Lieutenant Farrell had entered all the details in his flight log, including the fact that he hadn’t seen anything on the way back to DG. It was a copy of this report which was exercising the suspicious mind of Arnold Morgan right now in his command center.

He was bent over a large map pinned to a high, slanting desk with a light positioned right above. In his hand was a pair of dividers, and they were measuring out the distance from the Strait of Gibraltar to a point one thousand miles south of the Battle Group’s position at 1130 on June 28. He put that point at 9N, 67E.

He measured the distance, fifty-four inches on his map. He checked the scale—the distance from the Strait of Gibraltar to the point where Lieutenant Farrell thought he saw a submarine was 10,800 miles exactly. Everyone agreed it had probably been making eight knots through the water at periscope depth most of the way, sometimes in lonely waters a little faster, twice stopping to refuel. That meant it was traveling on average 200 miles per day.

Admiral Morgan divided 200 into 10,800 and came up with fifty-four days. He then checked his records for the precise time his operator had picked up the mysterious five-blader in the Gibraltar Strait—May 5 at 0438. From May 5 to May 31 was twenty-six days. The remaining twenty-eight days of June brought him to the precise time and date of Lieutenant Farrell’s sighting—June 28, 1130. 9N, 67E. “As blind coincidence goes, that one ain’t bad,” growled the admiral. And now he didn’t even bother with a telephone, just bellowed through the door at his Flag Lieutenant: “Try Rankov again…and don’t listen to any bullshit.”

Unknown to the lieutenant, this was going to become even more difficult, and embarrassing, as the day wore on. Because while Admiral Morgan was raging at the world in general, Admiral Vitaly Rankov, the six-foot-six-inch head of Russian Naval Intelligence, was spending much of it in an ancient converted military aircraft, rattling and shuddering its way due south from Moscow on a laborious eight-hundred-mile journey.

Admiral Rankov hated aircraft, almost as much as he hated Naval mysteries. Right now he also hated the persistent, ill-tempered, and irritatingly powerful American Intelligence chief, Arnold Morgan. Which, generally speaking, made the Russian three times more edgy than he normally was on an interior Russian flight.

Admiral Morgan was the only foreign executive who had ever snarled at him, and then threatened him. “Rankov…there are always two ways to do things,” Morgan had said. “The easy way and the hard way. If you do not do as I say in the next hour, I shall call my President, and have him call your President, and see how you come out of that little confrontation.”

Admiral Rankov had slammed down the phone, and called the American’s bluff. Two hours later he had indeed been in the Kremlin in front of the Russian President, and damned nearly got fired.

And now Morgan was being, for the second time in two years, a royal pain in the rear. He must have called Admiral Rankov’s office eight times in the last twenty-four hours. He had yelled at four different aides, and the Russian admiral knew precisely what he was asking: the same question he had been asking on and off for the last ten days—have you found that goddamned Kilo you told me you lost in the Black Sea ten weeks ago? Except that now he also wanted to know whether a drowned sailor washed up on some Greek island had been a member of that submarine’s crew.

Admiral Morgan’s last message had requested the name on the next-of-kin-list. This is the record every modern Navy keeps in case of a disaster at sea. The trouble was they did not seem to have a firm next-of-kin-list for the missing Kilo, which was at best tiresome, and at worst embarrassing in the extreme.

In fact the High Command of the Black Sea Fleet was useless. They had been unable to salvage, or even find, the missing Kilo. They had not even been able to trace the name of the drowned man. And there was the problem of the next-of-kin list.

They had the book at the base, and it contained a full crew list, but apparently they had not received the standard signal from the submarine, updating it before they left—recording perhaps a couple of men who had not made the trip, plus two or three others who were sailing but were not entered in the NOK list. Thus the whole system was out, every name was now questionable. Without the final signal from the Kilo, no name was definite, and the NOK list in their possession was too suspect to be quoted. As far as Admiral Rankov was concerned the drowned man could have deserted.

And now this American bastard was on the phone, and Admiral Vitaly Rankov considered it only a matter of time before he was back in the Kremlin to explain himself to the Russian President, and God knows who else.

Which was why he was now in this rattle trap of an aircraft flying to the Aeroflot terminal in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar, home, on the northern Caucasian plains, of the Kuban Cossacks.

It was also the nearest commercial airport to the port of Novorossisk, in which the Navy was conducting its endless meetings, discussing the possibility of resiting there a new Russian headquarters for the Black Sea Fleet. The long, laborious process of moving from historic Sevastopol, 250 miles west across the water in the Ukraine, had been driving everyone mad for eight years now, and nothing had been done, nor, in the opinion of Admiral Rankov, would ever be done.

The trouble was, no one knew what they were doing, nor indeed what they were expected to be doing. Thus you could never find anyone. Every time you wanted to see a high-ranking officer from the Black Sea Fleet, he was either in Sevastopol, or up in some shipyard gazing at an aircraft carrier which would never be completed, or wandering around Novorossisk talking rubbish about building projects no one could afford.

And now the admiral faced a seventy-mile car ride from Krasnodar Airport.

He must find out about the missing Kilo before Morgan caused an uproar. He regarded Morgan’s increasingly angry persistence as sinister. Something was going on, he knew that, but he did not want to get caught on the phone to Washington, probably being taped, with his pants down. A four-hour ride in that god-awful airplane had been preferable to that.

Admiral Rankov settled back in the deep and comfortable rear seat of the limousine which had arrived to collect him, right on time. He enjoyed the drive across the plains, and on down to the big commercial shipyard on the eastern shore of the great inland sea. He had been born just a few miles to the south in the lovely Russian resort city of Sochi, with its temperate southern climate and perfect beaches. The mountains, snow-capped and spectacular, lay to the northeast.

Right now, driving in some luxury into Novorossisk, with the warm southwestern breezes drifting across the sea from Turkey, and up the southern Russian coastline, Admiral Rankov wished no man ill. Except for Arnold Morgan, from whom there were already two urgent messages awaiting him at the temporary Navy yard reception desk.

“Jesus Christ!” groaned Vitaly. “Can I never get away from this fucking maniac?”

The SEALS sat together in the rear of the gigantic long-range Galaxy as it inched its way forward, twenty-five thousand feet above the Pacific Ocean. The forty-foot-long ASDS, winched on rails into this military freighter, was crated in a container in the hold. The SEALS sat in the close, silent camaraderie of fighting men who have nothing much to say to anyone except to each other. They wore their regular Navy uniforms, for a change. Also packed in the hold, with the miniature submarine, were crates containing the combat equipment they would use on their mission to disembowel the Iranian submarine service.

Each man owned a highly flexible, custom-made, neoprene wet suit, which provided excellent thermal protection; even eighty-four-degree water will sap the heat out of a man’s body if he stays in it long enough. The big SEAL flippers, for extra speed, were also custom-made. On the instep they bore the student number each man was awarded when he finally passed the BUD/S course. That lifetime identification number is worn with pride. At least 50 percent of every class fails.

All of Rusty Bennett’s men had with them a couple of modern commercial scuba diver’s masks, the bright Day-Glo orange and red colors carefully obscured with black water-resistant tape. Not one of the nine swimmers would wear a watch on the mission, because of the slight danger of the luminous dial being spotted by a sentry.

Underwater, SEALS travel with a specially designed “attack board,” a small two-handled platform which displays a compass, a depth gauge, and a more unobtrusive watch. The lead swimmer kicks through the water with both hands gripping his attack board, never needing to slide off course to check time or direction. These details are laid out right in front of his eyes on the board.

The second man usually swims with one hand lightly on the leader’s shoulder, both of them kicking and counting. SEALS have a special technique for judging distance. If one of them has to swim three hundred yards, and he knows he moves, say, ten feet forward with each kick, he knows he must count ninety kicks to be on top of his target. According to SEAL instructors, a trained underwater operative develops a near-mystical judgment of these relatively short journeys.

The SEALS would swim into Bandar Abbas behind four attack boards: three standard pairs, with the overall leader, Lieutenant Rusty Bennett, bringing in two men behind him. Each of them would carry the big fighting knife of their preference. The selected firearm weapon for this mission was a small submachine gun, the MP-5, made by the upmarket German gun company of Heckler and Koch, deadly reliable at close quarters, spot-on at twenty-five yards. Only three would be issued, one for Rusty and two extras for the rope-climbers. Their principal protection would be the dark waters of the harbor. Only in a case of dire necessity would the Americans open fire inside the floating dock.

Stowed separately in the hold was all of the SEALS’ destruction kit—five limpet mines, plus one spare, specially shaped for an upward blast, and reels of det-cord, cut into eighty-foot lengths. The specially prepared black nylon climbing ropes, with their steel grappling hooks, were stored in a separate wooden crate. Rusty Bennett had also packed two small Motorola MX300 radios, plus two compact digital global-positioning systems which display your exact spot on the surface of the earth accurate to fifteen feet. These satellite-linked electronic gadgets were regarded as a godsend by marauding SEALS teams, but unhappily did not work well underwater.

Lieutenant Bennett knew that the principal weapons of this particular hit team were stealth, surprise, cunning, and skill. He hoped not to need any extraordinary aids, except strength, brains, and silence.

The SEALS from Coronado landed at the American base on Diego Garcia at 2100, Saturday night, July 27. The thirteen-thousand-mile flight had taken thirty-four hours with a short delivery and refueling stop at Pearl Harbor.

After a light supper, they were ordered instantly to bed, in readiness for an 0600 departure the following morning, on board the USS L. Mendel Rivers. The 2,600-mile journey in the hunter-killer submarine would take them almost due north, up to the Gulf of Hormuz; five and a half days, running at twenty knots.

They knew it would be cramped because the 4,500-ton nuclear boat needed all of its 107 crew and 12 officers for a mission like this, which required the ship to be on high alert on a permanent basis. But at least the Mendel Rivers had been specially refitted to transport a platoon of SEALS. Each man would have a bunk, and Commander Banford was already in residence.

After six hours of sleep they awakened to a warm bright Sunday morning, the last daylight they would see for more than a week. Their equipment was already loaded and stowed, as the sun rose out of the eastern horizon of the Indian Ocean. The ten men stood on the dock and stared at the giant bulge on the deck right behind the sail. Inside, the miniature submarine which would take them in was already in place. While they had slept, a team had worked through the night unloading, uncrating, and lifting it aboard, ready for its final engineering check. Dave Mills would have five days to familiarize himself with the controls, but he was already trained to drive this new underwater delivery system.

They all knew the procedure. At the appointed time they would climb the ladder from the main submarine up into the DDS (dry deck shelter). There they would get aboard the tiny craft, and the hatch would be clamped into place. Oxygen supply would be checked, and the shelter flooded. Four divers would somehow wrestle her out into the ocean around thirty feet below the surface. Lieutenant Mills would fire up the engine and they would brace themselves for the uncomfortable thirteen-mile ride across the strait which divides Qeshm from Bandar Abbas.

It always felt freezing cold to the SEALS in an SDV, because the air they breathed came direct from a high-pressure storage bottle, and the temperature dropped noticeably in the manufactured, but normal, atmospheric conditions of the little submarine. The inner chill was always the same going in, and the SEALS knew this one would be no different.

The first three days of the journey to the Arabian Sea passed uneventfully. The submariners knew they were transporting the elite fighting men of the U.S. Navy, and the SEALS knew they were traveling with one of the most highly trained battle-ready crews in the world—officers who were also nuclear scientists, others whose knowledge of guided missiles was unrivaled, others who could diagnose the sounds of the ocean, sniffing out danger in all of its forms, often miles and miles away.

As Thursday night began to head toward Friday morning, nerves tightened. Commander Banford went over the plan again and again, until it was written on the heart of each SEAL. They were advised to sleep after an early lunch on Friday, and begin their final preparations at 1730. Each man should be ready by 1845, with his Draeger air system strapped on, the limpet mines, det-cord, ropes, grapplers, knives, and machine guns and clips buckled down, and waterproofed as far as possible for the swim. The official start time for the mission was 1900, at which time the ten men would enter the ASDS, just before dark.

During the final ninety minutes, the instructors and the Chief Petty Officer who had trained them never left their sides. The talk was sparse, encouraging, as if defeat was out of the question. The SEALS’ little corner of the SSN was like the dressing room of a world heavyweight champion, as each man prepared mentally in his own way. The atmosphere was taut, focused, as if deliberately ignoring the underlying fear of discovery, and probable death.

The rest of the submarine seemed quiet, but sharp, as the navigation officer guided her toward their waiting-station in the last deep water available to them…one hundred and fifty feet on the sounder. Position: 26.57N, 56.19E. Speed five knots.

The captain ordered them to periscope depth, grabbed both handles as the periscope came up from floor level. A three-second electronically coded message was fired up to the satellite for collection by the operators at DG, and a note was made of the flashing light guarding a sandbank off Qeshm Harbor, five hundred yards off their port beam. The periscope of the Mendel Rivers was down again within twelve seconds.

And now, with the ship silent with anticipation, the SEALS, faces blackened with water-resistant oil, began their climb into the dry deck shelter, an exercise they had been practicing three times a day since leaving DG. They slipped up through the hatch with slick expertise, and then climbed through the second hatch into the ASDS. Rusty and Lieutenant Mills occupied the two separate compartments in the bow, which housed the driving and navigation seats. The dry shelter flooded quickly, but the actual departure took longer than expected. Finally the divers pushed and shoved the little submarine clear, released the tether, and swam back to the shelter before the SEALS started the electric motor.

At 1937 they moved forward, course three-three-eight, which would take them on a dead straight line to the drop-off point outside the port of Bandar Abbas. Rusty put Lieutenant Mills on a course which would narrowly pass the shoals off the eastern end of the island of Qeshm, and they kept the boat running at fifteen feet below the surface.

Neither could see anything through the dark water, and the entire journey was conducted on instruments. Behind the two leaders, the eight SEALS could speak, and they could hear each other, but conversation was kept to a bare minimum. Noise, any noise, was magnified underwater.

The first two hours passed quickly, but everyone was feeling very cramped as Lieutenant Mills slid up to the surface for a “fix,” and then aimed the little boat across the final two miles to the harbor. They skirted the big sandbar which stretched in front of the entrance, and waited as the minutes passed until Rusty Bennett said softly, “This is it, guys. Right here.” Their position was 56.12E,27.07N. “We’re going to the bottom,” said Dave Mills. “It’s about forty feet. Stand by to flood rear compartments. Connect air lines, activate your Draegers, flippers on and fasten.”

All the men felt the little ship settle on the bottom. In the back they adjusted valves, shoved their feet into the flippers, clipped and fastened. Then they signaled everyone was ready. Lieutenant Mills opened the electronic valve and the seawater began to flood into the bigger “wet-and-dry-compartment,” and into the tiny one occupied by Rusty Bennett.

Neither space would be pumped out until the men were safely aboard after the mission. But Lieutenant Mills, in his little cockpit, would stay dry during his long wait for his charges to return.

As the pressure equalized inside and outside of the ASDS, the SEALS were now sitting like so many goldfish in a completely flooded area. Then the three hatches were opened, and one by one the SEALS popped out. Rusty was first, holding his “attack board” rigidly in front of him, getting the feel of the water, stabilizing his breathing, coming to an operational depth about twelve feet below the surface. If the oxygen in his Draeger was to last four hours, every action had to be steady and relaxed. Sudden panicky movements could drain it in sixty minutes.

Rusty felt his two colleagues touch him on either shoulder. The other six men he could see swimming into position right behind. And with long steady kicks the red-haired lieutenant commander from the coast of Maine began to drive his way toward the Ayatollah’s submarines.

He steadied the compass on bearing 284. There was five hundred yards to swim before the first turn. He hoped that he would be able to accurately judge the distance by counting his ten-foot kicks, and spotting the reflection of the green light on the harbor wall. Failing that, he would risk shoving his head above the surface to use a global-positioning device. He knew by a certain brightness in the water that the moon had risen, and he hoped to see the channel into the harbor.

They covered the five hundred yards in under fifteen minutes. Rusty spotted the green light through the surprisingly clear sea. Though the light seemed directly above, he knew it was fifty feet away because of the refraction effect of the water. He made his seventy-six-degree turn due north, fixed the compass bearing on zero-zero-zero degrees, and headed up into the harbor. With eleven hundred yards to swim, he had to concentrate. It was almost 2230, and would be a little after 2300 when they passed the next light. They would stay out in the channel away from the very shallow water for the following two hundred yards.

They swam, kicking steadily, breathing as they had been trained to. At this point, everyone knew for certain that their brutal training—the years of running, swimming, lifting, and the killer assault courses which had broken so many of their colleagues—was paying off as the nine SEALS made their way through the alien waters.

These men had not broken. If the pain of the long swim became too great, each would dig deeper, searching for and finding more willpower. Each was too proud, too brave, to fail.

They passed the light, kicking forward to the point where they would make a ninety-degree turn toward the inner harbor. Rusty was beginning to feel the pace now, but knew he must kick three hundred more times, and keep his breathing steady. He kept his eyes down and his mind clear, and he kicked and counted…kicked and counted…a nagging pain beginning to settle high up in both thighs.

He passed two hundred and fifty, and sensed his team was still together in a tight group. The last minute seemed to take an hour, and up ahead he could sense a long blurred line in the water. He made right for it…and came to a halt. It was a huge dockyard chain. Rusty swam to the surface, and looked around him. He was in the shadow of a gigantic floating dock and there seemed to be no light. The chain ran up to its stern on the basin side. The far side was even darker, closer to the jetty, and in deep shadow. He could see an engineer’s platform there, which almost certainly had a ladder into the water.

High above his head Rusty could see the ten-foot-long, scimitar-shaped blades of a propeller…five of them, engineered in bronze. It was the propeller of a Russian-built Kilo submarine.

Rusty dived again, swam across the stern of the dock, and climbed onto the deserted, unlit platform. He waited for his four black-suited colleagues. No sound passed between them. They unclipped their flippers and carried them into the great cavern of the dock. Each noted one single arclight positioned directly above the submarine, possibly fifty-five feet above the dock floor. The ship itself cast a giant oval shadow over the deck beneath. It towered above them, finely balanced, and it looked as big as a New York apartment block.

Four SEALS unclipped their Draegers, which weighed thirty-four pounds out of the water, and placed them with the flippers deep in the shadows of a dark corner. If any passing sentry as much as looked into that corner, they would blow a hole in his head with a silenced MP-5. With no Draegers, and no flippers, the SEALS would be marooned in this hostile, untenable land.

They whispered briefly. The four men would conduct a quick recce, prepare their climbing ropes, and place their det-cord in a handier place. Silently Rusty ran back to the starboard side, put his flippers back on, and slipped into the water without making a sound. He was carrying a limpet mine instead of his attack board. His target area was easy to locate, and he clamped the mine effortlessly onto the hull. He screwed a length of det-cord into the priming mechanism, and headed for the surface unraveling the cord as he went.

Rusty bobbed up right at the corner, tied his cord onto another piece being held five feet above him by one of the other SEALS, and headed for the portside platform. Back inside the dock, he removed his flippers and Draeger, and checked the clip on his MP-5.

The SEALS exchanged information in whispers. “There’s a guard with a machine gun up on the submarine…a chair right behind the sail facing aft…and there’s someone in that tower high up on the portside corner…. He’s not moving…but he may when the det-cord blows and splits those shores in half….”

All five had seen the four wooden targets, thirty feet above their heads, holding the great submarine in place, stark against the glare of the arclight. “It’s too bright…we’ll have to work real close to the hull…either that or shoot these two pricks before we start…there’s a ladder up the side of the dock right where we thought…in the middle…you’ll get a good view, Lieutenant…watch that fucker with the machine gun, willya? If that guy wakes up and as much as scratches his balls, he’s history…”

Rusty Bennett headed up the ladder. They were right. It was bright, but the shadow of the Kilo was protective. He could remain in that shadow and still see the head of the sentry. He hooked one leg and one arm through the ladder so that he could stand safely without using his hands, checked his gun, and aimed it carefully at the forehead of the dozing guard, sixty feet away.

He took his left hand off the weapon and placed his forefinger and middle finger in a V over his nose, signifying that he had the enemy in his sights. Then he raised his left arm and jammed his index finger in the air. “Go.” Immediately he heard the soft whirl of the roped grappling hooks as they circled clockwise. Each one flew up and over one of the four shores. They dropped quietly like spent fireworks, and for a moment he watched the four SEALS pull on the ropes. His heart beat faster as the black steel hooks bumped and then bit, hard, into the wood. No sound yet. No danger. Yet.

Rusty concentrated on his job, watching the sentry, but out of the corner of his eye he could see the confusion of pipes and equipment on the casing. There were huge gaps in the hull, several steel plates missing altogether, where a massive part had been removed from the interior. This was a submarine well into a six-month overhaul. To him, it was inconceivable that she had been fully operational, making her way back from the Arabian Gulf just twenty-four days ago.

Down below in the gloom he could just see his fellow warriors setting off, up the knotted ropes, each man moving carefully but relentlessly upward. They reached the shores at the same time, and Rusty saw them swing their right legs up and over the beams in a grotesque airborne ballet.

They each leaned forward, deeper into the shadow of the Kilo, clinging on with their knees like flat-race jockeys, pulling the det-cord up from the dock bottom. This was the tricky part, winding this explosive detonator line six times around the shores, while holding on to the rest, trailing below.

The SEAL on shore number two made the mistake. For a split second he lost his balance. With practiced skill he shoved the cord in his mouth and held it between his teeth, grabbing the beam with both hands to save himself from crashing thirty feet to the ground. The sure knowledge that no SEAL is ever left dead on the battlefield was no substitute for two-handed safety.

But the long end of the cord got away, and the whole sixty-odd feet dropped toward the dock bottom, landing noisily on the metal. The sudden sound of the cord hitting the deck, splitting the silence, terrified all five men.

Rusty Bennett lifted his left arm, fist clenched, fingers outward, the SEALS’ signal to “freeze.” But the armed guard on the submarine deck began to stand up, turning to his left, raising his machine gun in the approximate direction of the frozen SEALS. “Heh! Who’s there?” he suddenly called out. It was the last sound he ever made. Lieutenant Rusty Bennett shot him clean between the eyes, sending him backward over his chair with a leaden thump against the tower.

The silencer on the German weapon had done its job. The airborne SEALS had heard just the tiny, familiar “phuttt,” followed by the thud. There was no further noise as the four men completed their tasks of wrapping the cord around and around the shores. Six turns of that stuff would cleave the trunk of a big oak in two.

Rusty watched his men climb back down the nylon rope. Then he too descended the ladder and handed his machine gun to one of them while he went to work. He connected the four strands of det-cord in series. He took the end of the line of cord which went down to the limpet under the dock and tied that to the end of the line from the four beams. He took a further length of cord from his pocket and jammed it in between the rest and taped it firmly together.

That final piece of cord was then fixed into the timing mechanism, which Rusty carefully primed set for twenty minutes. No mistakes. No risks. Det-cord burned at five miles a second—when a bundle of it was wrapped together, as it was on the shore, it blew with serious impact. The SEALS all heard the almost soundless clock begin to tick.

“Now we’ve got ten minutes to get the fuck out of here,” whispered the SEAL leader. “Let’s go.”

They walked single file to the dark corner on the starboard side and put on their flippers. They replaced their Draegers, turned on the valves, breathed slowly, strapped the three guns on their backs, pulled down their masks, and lowered themselves over the edge. It was a five-foot drop. Rusty, holding the attack board in one hand, went first, taking his weight with his right hand still on the dock until the last second. He made hardly a ripple. The others followed him immediately, and they submerged together.

Rusty Bennett took a bearing of two-seven-zero and began the first of his three hundred kicks to the turning point out of the inner harbor. He guessed correctly that the other four SEALS, who had mined the two floating submarines, were somewhere out in front. They had clamped on their four limpets, primed and set them, and left the way they had come in. Probably went past the floating dock while Rusty had been connecting the det-cord.

He kicked, trying to gain as much distance as possible between his team and the dock when the det-cord blew. He guessed a quarter of a mile was the best he could hope for.

Meantime, high up in the tower on the seaward, port side corner of the floating dock, Leading Seaman Karim Aila, aged twenty-four, was reading a book. Every half hour or so he walked out onto his little balcony and gave a wave or a yell down to his colleague Ali, who was seated below the sail of the submarine. He could not see him, at least not while Ali sat in the shadow, but they usually shared some coffee every couple of hours on this long night watch, which lasted from 2000 to 0600.

No one else was on duty on the dock, though outside there was a fully staffed guardroom for the sentry patrols. Occasionally there would be a visit from a duty officer, but not that often. Iran’s Navy, eighteen thousand strong, and extremely well organized, tended to be a bit slack during the hours of darkness.

It was ten minutes after midnight when Karim heard the noise through his closed door. It sounded like a short, sharp but intense crack! Like someone slamming a flat steel ruler down hard on a polished table. He thought he heard a couple of dull vibrations far below, thuds in the night. He looked up, puzzled, put down his book, walked to the door, and yelled, “Ali!!” Silence. He gazed at the great Russian submarine. Everything seemed fine. Nonetheless, he decided to take one of his rare walks around the upper gantry of the dock.

He popped back inside to collect his machine gun, and set off down the long 256-foot port side, passing under the big lifting crane. He did not see the crumpled figure of his dead friend lying against the tower of the sail. At the end of the walkway he made his turn and walked slowly across the narrow end of the dock, staring down at the motionless bow of the submarine. He had traveled about fifty feet along the starboard side when he noticed the first shore was missing. He peered over the edge and could see at least one piece of the wooden beam lying in the glow of the arclight far below on the steel deck.

That was it. That was the crack he had heard. The shore had fallen out. Karim did not wait around. He raced back along the walkway, up the circular steps into his control room, and grabbed the phone. Then he saw it…a red light flashing, indicating one of the starboard tanks was either malfunctioning or filling with seawater.He slammed the phone down, and crossed to the screen which showed the horizontal level of the dock.

“My God!!” She was listing one quarter of a degree to starboard and still moving. Karim knew what to do. He must flood the portside tanks instantly to stabilize the dock, level her out. He grabbed for the valve controls…but he was too late.

There was something terribly wrong. Outside there was more noise, a kind of heaving and wrenching.

He dived through the door, and before his eyes the huge submarine began to move. Karim stood transfixed, horrified, as the Kilo gathered speed, toppling sideways to starboard. All two and a half thousand tons of her was twisting downward as if in slow motion. The sail smashed into the steel side of the dock, buckling it outward, and ripping the tower clean off the casing. Then, almost in slow motion, the hull of the submarine crashed down to the floor of the dock in a mushroom cloud of choking dust and a thunderous roar of fractured, tearing metal. Her entire starboard side disappeared as the dock floor completely caved in.

Karim Aila felt the whole dock shudder from the impact, and then lurch as the sea rushed in through the gaping breach below the wrecked submarine. He was afraid to run, afraid to stay where he was, because it seemed the dock would capsize. The submarine, her hull irreparable, her back broken, her tower hanging up the side of the starboard wing wall, was already half under water. Karim debated whether to jump the eighty feet into the harbor, or try to walk back along the grotesquely tilted gangway. He gazed down, turned away, and went for the gangway, inching his way along. He made it fifty feet before the huge lifting crane directly in front of him suddenly ripped away from its ten-inch-wide holding bolts and plummeted downward like a dying missile.

The massive steel point of the crane, built to withstand the full lifting-weight, came down from a height of eighty feet and speared straight through the thick pressure hull on the port side of the stricken Kilo—an already dead whale receiving its last harpoon.

Karim still clung to the high rail, now only thirty feet above the water, as the dock settled on the floor of the harbor. The control tower was angled out like a bowsprit, and since there was now no way of reaching the jetty, the young Iranian climbed back to it. He sat on top, precarious, but safe; surveying the scene of absolute catastrophe over which he had presided.

Rusty Bennett kept swimming and kept counting. The five SEALS reached the first turning point and set off, due south, out of the harbor. They had been back in the water for one hour, when Rusty made the left turn toward the ASDS. Five hundred yards to go. And now he was listening—listening for the regular light-frequency “peep-da-peep-peep” of the homing signal which would guide them in. When he heard it once, he would hear it every thirty seconds. Rusty picked it up while they were still in the shadow of the harbor wall.

The rest was routine. Lieutenant Mills saw them from his cockpit as they moved around the hull and climbed into the open, flooded compartment. The other four SEALS were already in place, and offered a cheerful “thumbs-up.” Rusty clambered into his solo navigation compartment, and each man seized the air lines to the central system.

Dave Mills now closed all canopies, and they heard the hum of the pumps as the water was drained out and replaced by air. The compartment was quickly dry again, and as the little ASDS crawled away at her five-knot maximum speed, Rusty Bennett said simply, “Well done, guys. How long before the other two blow?”

One SEAL in the back answered succinctly. “0145. Thirty minutes from now.”

Rusty made a few calculations in his head. He guessed that the Iranians were not at this point even considering they had lost their Kilo by any kind of military action. The submarine had somehow fallen and that was that. But when the next two exploded, burned, and sank, the Iranian Navy would arrive at the inescapable conclusion. The issue was, how soon?

Commander Banford and Rusty had gone over the main strength of the Iranian Navy several times. In addition to the three Kilos, they also ran two guided missile destroyers, three Royal Navy-designed frigates, two Corvettes, and nine midget submarines. They had a ton of coastal patrol boats, and a lot of backup auxiliaries.

Rusty knew the frigates were the problem. Built in the late 1960s, by Britain’s vastly experienced Vickers Corporation in Newcastle and Barrow, these streamlined three-hundred-foot Vosper Mk-5’s could make almost thirty-five knots through the water. Worse, they carried an anti-submarine mortar, a big Limbo Mark 10, which contained two hundred pounds of TNT. Fired from the stern, these things had a range of more than a thousand yards and exploded at a preset depth. With a bit of luck on their side, they could blow a submarine apart. But they could kill a diver at five hundred yards. Rusty Bennett dreaded those fast frigates, and he ordered Dave Mills to drive the last half hour as deep as possible.

The Iranian frigates could cross the strait from Bandar Abbas to the eastern end of Qeshm in twenty minutes flat. He estimated it would take them one hour to get the crew organized and get under way—one hour from the explosions under the last two Kilos…one hour from 0145. In Rusty’s opinion that could, theoretically, put a high-powered Iranian mortar bomb right in the water close to the waiting-station of the Mendel Rivers by 0310.

Right now it was 0130 and they had a two-and-a-half-hour run in front of them. The ASDS was due to dock at 0400. Rusty tried to juggle the figures, tried to imagine the uproar in the Naval base, tried to imagine how quickly the admiral in command could get his act together. “I suppose it might just take ’em sixty minutes at this time of night to get a damage check from the experts. Then I guess it could be another hour to get one of those frigates moving,” he thought.

“But, Jesus. Any damn fool who’s lost his entire submarine fleet could work out that the attacker must have arrived in a submarine himself. And where is that submarine? He’s right out there in the first deep water you come to, right off the coast of Qeshm. That’s where he is. And he’s waiting for his demolition guys to get back, riding in some kind of a midget submarine. I know what I’d do. I charge out there and bombard the area with mortars. If I had three of those frigates available, I’d send ’em all. I’d definitely catch the divers, and I might get the big submarine, too.

“If the Iranian is sharp he will pass us overhead an hour before we reach the Mendel Rivers. If he’s unsharp, he might not get there until 0410, in which case he’s gonna be a bit late, but still dangerous. Either way we’re in dead trouble…step on it, Dave, willya?”

The limpet mines beneath the Kilos blew, precisely on time. Both submarines were almost split in two. Both batteries were blown apart. The interior fires were still raging as they each sank beneath the dark waters of the harbor. The Iranian admiral, called from his bed to inspect the wrecked dry dock and the written-off Kilo, very nearly had a heart attack when the other two joined them on the bottom.

Every light in the harbor was on. The admiral wanted to know whether the radar sweeps had found any contact whatsoever throughout the night. No one had seen anything, heard anything, done anything, or knew anything. He called a meeting of the High Command. He placed a call to the Iraqi Naval Base at Bazra, where the operator inquired irritably, was there a lunatic on the line.

Slowly his commanders began to appear on base. But it was not until 0315 that anyone asked the three pertinent questions. It was a young Iranian captain who wondered, “Who did this? How did they get here? And where are they now?”

And it was not until 0405 that one of the frigates was under way, speeding toward the deep water where the admiral now assessed any marauding submarine would be.

The Americans had just docked the ASDS as the Iranian warship left. Too late. Commander Banford and the captain were already moving south, running deep, at twenty knots in the nuclear-powered Mendel Rivers. They had a twelve-mile start, and the strait grew wider and deeper with every turn of the propeller. And the Iranians did not know what they were seeking, nor indeed what to do if they found anyone.

Twenty minutes after they set off, the crew of the Mendel Rivers heard the first wild mortar shot explode, far back and deep. But the Iranians were much too late.

The SEALS were safe, the mission was completed. “Nice job, Lieutenant,” said Commander Banford.