Shame is a soul-eating emotion.

The ‘Red Book’ or Liber Novus, Carl Jung, possibly between 1915 and 1930

‘When I went into the fashion industry, I was told I was gigantic, and that my body was letting my face down. I started to resent my body – it was like my head and my body were two separate entities and they were at war with each other. And I met people who were doing insane things to keep looking the way they did, but over time I came to realise that this is what you had to do to be as thin as they are. At first it was an eating disorder I pieced together by copying the people around me. Over time it became a way to punish myself for what was going on in my head. And that’s when I really got myself into trouble – it was more like self-harm. At one point I had a hole in the roof of my mouth that had been eroded by vomiting. I was in hospital twice – once because I was so dehydrated and once because there was a tear in my oesophagus.’

Anonymous interviewee ‘B’

Eating disorders seem like a step away from the real world: an escape into a way of thinking which is entirely alien to most of us. As a whole they seem completely self-defeating, yet they unnerve us because they carry within them little nuggets of logic – tiny slivers of the behaviours we all use to pick our way through the tangle of food, mood and shape.

Few women eat blindly and without consideration – almost all think about what effects the food they eat will have on their body shape. Wanting to moderate one’s diet and shape to the ‘right’ levels is almost universal, but when does that desire become pathological? Is there a clear boundary beyond which things get out of control and spiral into uncontrollable starvation or bingeing? Or is there a continuous spectrum of behaviour between ‘normal’ and ‘pathological’ eating with no clear demarcation between the two?

Many women assume such a clear boundary exists, and like to think it presents a reassuring barrier to prevent them accidentally slipping across to the other side. Also, a clear distinction between ‘normal’ and ‘disordered’ eating would imply that eating disorders are caused by clear-cut genetic, neurological or psychological factors, rather than intangible social and cultural influences which could trip up any woman at any time. Life would be less worrying if eating disorders were neat, distinct abnormalities which can affect only an unlucky few, yet in recent years the suspicion has deepened that eating disorders are, in fact, very messy indeed.

My aim in this chapter is not to provide an exhaustive account of eating disorders, but rather to address a few especially disquieting questions which relate to my wider investigation of female body shape. Are eating disorders entirely different from normal patterns of eating? Do they have a simple biological origin somewhere in the body or brain, or is there more to them than that? Why do they predominantly affect women? And why on earth did the human species evolve to allow such futilely destructive suffering?

It is difficult to formulate a catch-all definition for eating disorders. For a start, they involve a failure to cope with one’s own body image. This is something they share with Body Dysmorphic Disorder, but while that disorder singles out particular parts of the body for criticism and distress, eating disorders are directed at the body’s global shape and size, and the role of food in creating it.

There are several different eating disorders, but I will concentrate on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The words ‘anorexia’ and ‘bulimia’ mean ‘not eating’ and ‘ravenous eating’, and ‘nervosa’ simply reflects the assumption that their basic cause lies inside the brain. Anorexia and bulimia are linked, share some features in common, and as many as a third of sufferers may migrate from one disorder to the other, yet they also exhibit differences which set them apart from each other.

Many psychiatrists take a rather ‘tick-box’ approach to diagnosing illness, and their four defining characteristics required for a diagnosis of anorexia are extremely low weight, a cessation of menstrual periods, a fear of gaining weight, and a distortion of perceptions of body weight. Anorexia sufferers may reach and maintain their low weight by restricting their eating, or by purging any food they do eat by vomiting or taking laxatives. They often show an obsession with a restricted set of particular foods, may hoard food, eat extremely slowly, may not swallow food, or may regurgitate it to rechew it or discard it. They often take steps to conceal their behaviour, and may wear baggy clothes or adopt particular postures to hide their body shape. They are prone to weakness and dizziness, and suffer from hormonal disturbances which can lead to, among other things, stunted growth and osteoporosis. Anorexia nervosa probably has the highest suicide rate of any mental illness.

Bulimia nervosa is rather different. Its ‘tick-box’ definition has three elements – bingeing with high-calorie foods at least twice a week; ‘cancelling out’ those calories by purging, laxatives, enemas, starvation or exercise; and a strong tendency for self-worth to be based on body size or shape. On average, bulimia starts at greater age than anorexia, and sufferers are usually a fairly normal weight – they fear gaining weight, but do not particularly strive to lose it. The binges may contain between seven and ten thousand calories, but this varies a great deal – what seems to be important is that they are perceived as binges. Most bulimia sufferers induce vomiting to purge food, often more frequently than once a day, and this leads to most of the adverse physical effects of the disease – calluses form on the knuckles, gastric acid demineralises tooth enamel, electrolyte imbalances disturb the normal heart rhythm, and the stomach and oesophagus may rupture.

At first sight, the behaviours associated with eating disorders may appear completely alien to other people, yet the distinction between normal and abnormal is not at all clear. First of all, there exists another diagnostic category called ‘eating disorder not otherwise specified’ which includes people who exhibit abnormal eating behaviours but do not meet all the criteria for a formal diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia. While this probably just represents the limitations of using a crude ‘tick-box’ diagnostic system, more worrying is the idea of ‘partial eating disorders’ – an undefined but potentially large group of people who display some of the symptoms of anorexia or bulimia, sometimes for many years. I suspect that it is this hidden reservoir of uncounted sufferers which makes the published figures for the incidence of eating disorders seem strangely low – 0.1–0.5 per cent of the population with anorexia, and 0.5–1.5 per cent with bulimia. Certainly, when interviewing women for this book, every single one of them knew a close female friend or a relative with an eating disorder.

One further feature of eating disorders deserves particular attention because, as we will see, it may relate to the possible origins of these diseases: exercise. Many people diagnosed with eating disorders, and many women who are simply dissatisfied with their bodies, take a great deal of vigorous exercise in an attempt to change their shape. And their relationship with exercise changes fundamentally: ‘exercise dependence’ is diagnosed when the main aim of exercise is to induce weight loss or shape change, and when an exerciser feels guilty when they do not exercise. Many people with exercise dependence, especially women, will exercise while injured, or miss out on social events because they are exercising. Some women become exercise dependent as part of an eating disorder, but for many it works the other way round – they develop an eating disorder as a result of their exercise dependence.

Although different studies vary in their estimates of how common eating disorders are, they all agree on one thing: they are approximately ten times more common in women than men. The fact that some men do get these disorders is helpful in our attempts to understand them, but the existence of this sex-skew in a species with such an unusual female body shape is suspicious, to say the least.

Just as the symptoms of eating disorders are extremely variable, so is the course of these diseases. Some women suffer a single, brief episode, whereas others live with an eating disorder for decades. A ‘typical’ eating disorder may last for six years or so. Many, but certainly not all eating disorders start during the second decade of life, and their incidence slowly decreases thereafter. Eating disorders tend to start earlier in girls who undergo puberty earlier, but by the age of twenty those girls are no more likely to have an eating disorder than their later-developing counterparts. Eating disorders dramatically reduce fertility, but if sufferers do become pregnant it appears that, on average, the symptoms of eating disorders recede, and may even disappear. Wherever eating disorders are concerned, however, there are always exceptions – and some women suffer from an eating disorder, ‘pregorexia’, in which they starve or purge in an attempt to prevent the (natural) weight gain that comes with pregnancy. After pregnancy, some women report that their eating disorder remains quiescent while they are caring for their children, but reverts to its original severity once those children leave home. Eating disorders are less common in middle and old age, but they are not rare. Sufferers in these age groups have been largely ignored by the media, who presumably find diseases of older women less tragic, and by researchers, who often base their research on a convenient supply of female university students.

So eating disorders are strange, dangerous, intriguingly variable, either rare or common depending on how you define them, and predominantly affect women. They also involve patterns of disordered thought which make them look like mental illnesses. This, and the desperate desire for successful medical treatments, have led to an enormous amount of recent research into the biological basis of eating disorders. In the past, scientific studies have shown us that many other diseases have single biological, organic causes, and this knowledge has often led to miraculous cures, but things have not turned out that way for eating disorders. Not yet, at least.

There is good evidence that eating disorders have a heritable genetic basis. Studies of identical and non-identical twins who are raised together or apart, and statistical analyses within families, suggest that genes could be the biggest single factor underlying eating disorders. An individual is much more likely to suffer from an eating disorder if they have a close relative who is also a sufferer, and this effect is not explained by them living in a similar environment. Unaffected family members tend to share many of the character traits which predispose to anorexia or bulimia. Even traits as apparently complex as the tendency to relate one’s shape and weight concerns to one’s self-worth have been shown to be strongly inherited. In striking contrast, childhood eating disorders (which are rarer) do not appear to have a heritable basis at all.

Although finding the individual genes behind inherited eating disorders has proved frustrating, the general power of genes seems very clear and those that have been identified so far are a thought-provoking bunch. The best candidate gene is ‘SLC6A4’ which is involved in the transport of serotonin – the brain chemical we saw in the last chapter is involved in mood and appetite. However, although the statistical link between variants of this gene and eating disorders is clear, it is not powerful – variations in the gene exert only small effects on women’s chances of developing eating disorders. Another candidate gene, ‘COMT’, is involved in the breakdown of brain chemicals similar to serotonin, such as dopamine, while the ‘ESR’ genes, which produce the receptor proteins which allow oestrogens to act on cells, have also been implicated. Despite this initial success, we should not expect this gene-search to produce simple answers – after all, any single, simple gene defect which caused something as damaging as an eating disorder would have been lost from the human population long ago.

As well as genes, personality traits have also received a great deal of attention as possible causes of eating disorders. Girls and women who have eating disorders tend to be perfectionists, to be anxious, and to display psychological rigidity in the face of change – all characteristics which can be measured by objective tests. It has also been claimed that they are more likely to show characteristics akin to autism. This does not mean that eating disorders and autism are the same thing, but it is notable that people with both conditions often see their ‘condition’ as ‘part of themselves’, rather than as a disorder or disability.

Studying the role of personality in eating disorders has led to two important realisations. The first is that these personality traits are demonstrably present before, and often long before any behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms occur. The fact that they pre-date any starvation or bingeing means that, although these traits may be exacerbated by the severe physical effects of eating disorders, they are not caused by them. The second realisation is that ‘control’ does not seem to feature highly in scientific analyses of eating disorders. We are often told that anorexic girls behave as they do because diet is the one thing in their lives they feel they can control, yet the evidence to support this is lacking. Indeed, I have spoken to anorexia sufferers who were adamant that their condition involved an unpredictable, unplanned and shockingly sudden loss of control over food. Admittedly, many pro-anorexia and pro-bulimia websites strongly promote the idea of control to their readers, but ‘control’ is not the universal initiating factor it is often claimed to be.

Some of the most intriguing insights into eating disorders have come from studies of brain function. These studies provide very real and specific insights into the mind of anorexic or bulimic women, which go some way to explaining the unusual nature of these disorders, and they also raise the possibility of developing targeted medical treatments.

However, before I describe them, I should mention one important caveat regarding these neurological findings. Because definitively diagnosed eating disorders are quite rare, it is extremely difficult to conduct a study in which detailed neurological data are gathered from women before they develop these conditions. Even a large study which follows hundreds of girls through childhood and puberty is likely to end up with fewer than ten girls with tick-box-diagnosed eating disorders – probably not enough to provide any meaningful information. Because of this, all the brain alterations so far associated with eating disorders could be the result of starvation or bingeing or purging, rather than the cause. For example, the brains of women with anorexia are smaller and contain larger internal cavities, but this is probably because anorexia causes the brain to shrink, rather than the other way around.

The first cognitive abnormality seen in eating disorders involves abnormal perceptions of body shape and size, and indeed in some cases this could be the key to the entire disorder. Sometimes women with eating disorders recount moving experiences in which they accidentally glimpsed a woman whom they considered to be abnormally and unpleasantly thin, only to discover that they were unknowingly looking in a mirror. Such body shape ‘epiphanies’ are evidence that some women with eating disorders drastically overestimate their own body size due to an inherent abnormality of self-perception. And experiments with computer-distorted images of sufferers’ own bodies confirm that, on average, anorexic and bulimic women do indeed overestimate the real size of their own bodies. However, size overestimation is not a consistent finding in all women with eating disorders, so it is not the defining feature of these conditions that it is sometimes suggested to be.

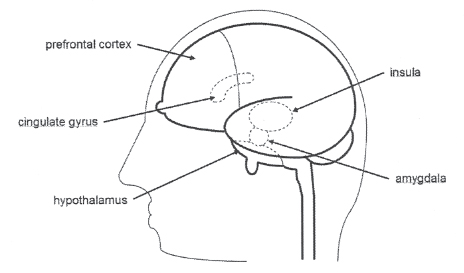

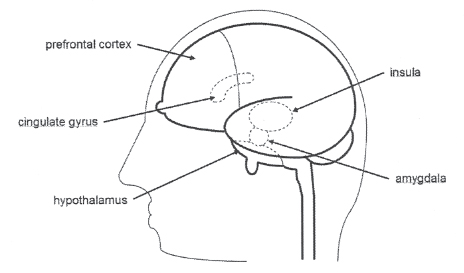

Such perceptual deficits appear to be specific to bodies and food. Women with distortions of body perception are usually able to accurately assess the size of neutral objects, such as vases. For example, brain scans show that the cerebral cortex in anorexic women is less activated by images of food or other women’s bodies, suggesting that they are selectively ‘blunted’ to these stimuli. Conversely, when women with anorexia view images in which their own body shape is computer-distorted to look larger, one brain region, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (see picture) becomes unusually active – and the more severe their anorexia symptoms, the more excessive this overreaction is. Brain regions known as the insula, hypothalamus and amygdala also exhibit reduced responses when women with anorexia are asked to think about eating, while the insula also responds more weakly to the taste of high-calorie foods in the mouth. The insula is probably involved in seeking out desirable foods, but as we have seen previously, it may also play a role in women’s sense of body-ownership.

Some perceptual abnormalities in eating disorders appear more complex. Studies in which women’s gazes were tracked as they looked at their own bodies and the bodies of others show that eating disorders entail an unusual selectivity about what is being looked at. Women without eating disorders spend more time looking at the parts of their own bodies which they perceive as ‘beautiful’ than parts they find ‘ugly’, and they do the opposite when looking at other women’s bodies. In contrast, women with eating disorders concentrate on ‘ugly’ bits of themselves and ‘beautiful’ bits of other women. And perception in eating disorders is also mysteriously linked to apparently unrelated aspects of brain function – for example, women who are strongly biased towards being right-handed are more likely to perceive their own body shape inaccurately and, as a result, exhibit symptoms of disordered eating.

The second group of brain abnormalities involves cognition – higher level processing of information about the body, including interpreting and assigning importance to its shape and size. For example, some anorexic women perceive their body size correctly, yet still believe it is not too thin. Also, many women with eating disorders have overly strict ideas of what constitutes an ‘ideal’ body, or over-emphasise the importance of body shape to their self-worth, happiness and success. A quick internet search for ‘pro-ana’ websites quickly demonstrates how some anorexic girls and women believe that bones are white and clean and beautiful and should be seen through your skin, whereas fat is disgusting and evil and makes everyone, including boys, hate you.

It may come as no surprise that women with eating disorders exhibit skewed cognitive responses to bodies and food, but eating disorders also seem to involve more general abnormalities of high-level thought. For example, women with anorexia perform less well on tests of almost all aspects of higher cognitive functioning, including memory, attention, abstraction, visuo-spatial ability and synthesising information from different sources. Also, just thinking about eating food induces abnormally exaggerated responses in the prefrontal cortex of women with anorexia, almost suggesting that they ‘over-think’ food with their higher cognitive areas, rather than savouring it with their baser brain regions. Many of these cognitive abnormalities persist even after eating disorder episodes have ended, which raises the possibility that they may also have been present before the disorders ever started.

The third and last set of brain abnormalities seen in eating disorders involve altered emotions – especially shame, disgust, anxiety and self-consciousness caused by food or the idea of weight gain. Many of us experience mild versions of these emotions quite frequently, but they come to dominate the lives of women with eating disorders. Food and weight can also independently affect our emotions in different ways – many children, for example, are repelled by the idea of eating certain foods, but not usually because they think they will make them fat.

In recent years, neuroscientists have actually located the regions of the brain involved in emotion – a list of regions which partially overlaps with areas we have encountered already: the insula, amygdala, prefrontal cortex and cingulate gyrus. It had been suspected for some time that women with eating disorders exhibit more negative emotions when standing in front of a mirror, or have trouble interpreting social cues from the people around them, but we can now watch these responses taking place in real time, inside living brains. For example, the amygdala, a region involved in fear and disgust, seems to be more active in women with anorexia. Also, comparison of pictures of oneself and others’ bodies leads to distorted patterns of activation throughout the ‘emotional’ parts of the brain.

Amine chemicals in the brain, such as serotonin and dopamine are increasingly implicated in emotional abnormalities in eating disorders. These chemicals underlie diverse brain networks involved in, among other things, mood, appetite and impulsivity – and their patterns of activity are obviously altered in both anorexia and bulimia. The effects of these chemicals are extremely complicated, which probably explains why crude attempts to use serotonin-altering antidepressants to treat eating disorders have proved rather unsuccessful. Instead, alterations in these chemical systems should perhaps be seen as reflecting general shifts in the complex way the mind thinks about food – a tussle between the ancient brain centres of hunger, appetite and emotion, and the more recently evolved regions of ‘higher’ thought and control.

So the biology of eating disorders remains confusing. They have a clear genetic basis but we cannot find many good candidate genes; there are predisposing character traits which underlie them but we do not know why; and despite many striking neurological findings we have discovered no single brain abnormality which causes anorexia or bulimia. This lack of success could be because we simply have not yet looked hard enough, or maybe, all along, biology was the wrong place to look.

And some claim that biology is indeed the wrong place. Instead of a gene, or a brain abnormality, should we instead be seeking social or cultural explanations for eating disorders? Environmental triggers and cultural pressures may sound wishy-washy, but they can be powerful.

Some women recollect a specific environmental cue which they believe drove them to initiate their disordered eating and calorie purging. Conversely, many women can recall no such cue – their anorexia or bulimia seemed to come entirely out of the blue. And even for women who do believe there was a specific trigger for their disorder, the variety of possible cues is bewildering. Often it is thought that exposure to a single image of a female body – either their own or someone else’s – set them on a one-way road to abnormal eating habits. Others believe that being overweight as a child was the trigger (and there is some evidence that this can indeed be the case). Perhaps surprisingly, factors such as parental death or childhood sexual abuse do not seem to correlate with subsequent incidence of eating disorders.

Being teased about one’s body shape has often been linked to the onset of eating disorders, although such teasing is so common that this is hard to prove – one study suggested that 13 per cent of girls are teased about their body shape by their mothers, 19 per cent by their fathers and 29 per cent by their siblings. Some girls even thought that their mother’s eating habits were a contributing factor. And most worryingly of all, many women believe it was an initial, apparently innocuous, teenage attempt to diet which got them hooked on controlling their food intake and body shape.

There is a persuasive argument that, rather than providing single provoking triggers for eating disorders, modern society and culture impose a global obsession with feminine thinness and food-denial which both causes and perpetuates eating disorders. In other words, women with anorexia or bulimia are simply individuals who happen to lie at the vulnerable end of the spectrum of women’s reactions to the cult of thinness in which they all find themselves. So perhaps eating disorders are simply an exaggerated form of the shape-sickness which afflicts society.

With that in mind, there may be several reasons why girls and young women develop pathological eating and shape-control habits, but all of them involve attempts to challenge external expectations of the female body. Girls often start to show signs of eating disorders around the time of puberty – a phase when they are being pulled away from the relatively androgynous slim body shape of childhood and towards a more curvaceous, womanly figure. Alternatively, eating disorders could be a way to reject the feminising effects of puberty – a rejection of curves – or an attempt to recreate the blissful sexlessness of infancy when girls and boys did not seem very different. Maybe in a culture in which women are often judged solely by their distinctive body shape, girls believe that by actively expunging that shape they can liberate themselves so they can be appreciated for their achievements instead. Or possibly, when society frowns on teenage sex for girls (but not boys), could eating disorders be a way to avoid sex?

The idea that our modern developed society and culture cause eating disorders is disturbing, partly because it forces us to face the extreme pressures we put on women, especially young women, and partly because it makes us realise that many of the ‘distorted’ attitudes of women with eating disorders are, in fact, valid – people do treat slimmer women better, they do think more of them, and women can become slimmer by manipulating calories. Accepting a social cause for eating disorders also implies that no one is safe from these malign influences: you can evade a bad gene, but you cannot evade society. And women do not have to be diagnosed with a disorder to feel these pressures – many women who consider themselves ‘normal’ engage in some fairly drastic methods of weight control.

Supporters of the social theory claim that it explains many strange features of eating disorders – especially why they are more common in women living in developed countries, and young, intelligent, educated, affluent women at that, and why they have become increasingly common in recent decades as the cult of thinness has taken hold. Indeed, these are often seen as the defining social features of anorexia and bulimia, yet whether they do indeed preferentially affect the rich, developed and educated is still open to debate.

Similarly, although some medical data might make us believe that anorexia and bulimia are essentially modern disorders which only became common within the last fifty years, this may reflect changes in attitudes or diagnostic criteria rather than actual prevalence of the disorders. Anorexia was first medically described in 1868 (as ‘apepsia hysterica’) and bulimia, remarkably, not until 1979. However, closer inspection of written records has led many to claim that both conditions can be traced back to the Middle Ages, and even before, possibly with rates of incidence just as high as today. ‘Holy fasting’ was commonly reported in girls in medieval Europe, and many died as a result. Indeed, many Christian saints were young women who starved themselves to death in the name of God.

Thus, while social and cultural causes could explain socio-economic and historical variations in anorexia and bulimia, first we do need to be clear that those variations actually exist. Also, at first sight, these theories cannot explain why men sometimes get these purportedly culture-inflicted, female-focused disorders. Unlike girls, the bodily restructuring of puberty is almost universally welcomed by boys – boys generally want to be tall, muscular and deep-voiced – so what cultural pressures are they reacting against? Some have pointed out that many male eating disorder sufferers are homosexual or make their living from dancing or acting, and that they thus represent unusual male subcultures to which different rules apply. However, there is evidence that eating disorders are becoming more common in the male population as a whole too, and some have ascribed this increase to a greater prevalence of images of fatless male bodies in the media – exactly as is claimed for eating disorders in women.

The most confusing aspect of eating disorders is why they occur at all – how humans evolved into creatures who could suffer them. This is the side of anorexia and bulimia which interests me most, because it strikes at the heart of what it means to be a human female and to balance the ancient conflicting demands of food, shape and success in a modern, unnatural world.

No animal evolves specifically to suffer bouts of starvation, bingeing, emaciation, infertility and death, yet that is precisely what some women now do. However, all current human behaviours occur in the context of our evolutionary inheritance from the last few million years. Even if full-blown eating disorders have only existed for the last five decades (which I suspect is unlikely), then they must still be the product of a female brain honed by aeons of natural selection. The socio-cultural pressures on women today must act on something – and that something is the physical and mental adaptations which once helped their prehistoric female ancestors survive and thrive. This does not mean that eating disorders are advantageous today, but I strongly believe that elements of them must have proved advantageous at some point in the 99 per cent of our history when we were hunter-gatherers. Anorexia and bulimia did not appear out of nowhere.

There are two main types of evolutionary theory which attempt to explain the origins of eating disorders. The first set of theories emphasise the idea that food supply was intermittent for much of human history – that our ancestors experienced alternating periods of plenty and scarcity. This could have been because some foods were only seasonally available, or it could just be because climate and food supply were generally unpredictable.

One theory posits that alternating episodes of bingeing and starvation were a normal feature of pre-agricultural human life, and that we retain a propensity for this behaviour today. This could certainly explain why bingeing is a natural behaviour – storing valuable calories when times are good – but self-starvation seems harder to explain. However, there is clear evidence from the natural world that abstinence from food can be a normal, inbuilt urge too. For example, many animals reduce their appetite in anticipation of food scarcity – well-fed deer eat less in the winter simply because their ancestors lived in an environment where food was scarce at that time of year. In other words, animals do not waste energy seeking food if their genes programme them that it is not to be found. So it is entirely possible that both the bingeing and starvation seen in eating disorders could be evolutionary relics of a time when our food supply was unpredictable.

Another, perhaps opposing theory based on erratic food supply relates to the over-exercising and hyperactivity seen in some eating disorders – women with anorexia, for example, often pace around unnecessarily to burn off extra calories. According to this theory, hyperactivity is a normal response to food scarcity which encourages famine-stricken human populations to move, literally, to pastures new. And seeing a few emaciated women in their midst may have been enough to convince ancient tribes that it was time to move or die. Thus women with eating disorders were like canaries in a coal mine – hypersensitive individuals who warned of impending doom. There are some who suggest that anorexic women were actually the people who energetically uprooted their starving yet lethargic kinsmen and led them to the promised land. This is a strange notion, and it obviously does not explain why so many women self-starve when food is plentiful. However, there is experimental evidence that rodents, too, become overactive and increase food-seeking behaviour when starved, although well-fed lab rats do not spontaneously become anorexic in the first place.

The final food-supply-based theory puts even more emphasis on the importance of human social groups. Indeed, it is predicated on the assumption that being a member of a tribe or social group is absolutely essential for a woman’s survival. This hypothesis suggests that for some women, eating less is a natural response to reduced food availability, which stops them competing with other people in their social group and thus risking expulsion. This idea seems strange at first sight, but it must be admitted that we do not know what awful things ancient human tribes might have done to individual members in their desperate attempts to avoid starvation. This theory has the added advantage that it could explain why women start to restrict their eating in the first place. It also suggests that women may continue to under-eat even once food supply has increased, to avoid socially threatening competition for food with men who are larger, angrier, and presumably now less starvation-weakened than them. According to this idea, exclusion from the tribe is a greater risk than under-eating.

The second group of evolutionary theories for eating disorders relates to reproduction. Certainly all animals must have pre-programmed instincts to stop eating – otherwise they would never have time to breed, or perform other essential activities. This of course could explain why eating disorders often start during puberty, as this is a time when teenagers’ thoughts naturally turn to sex. However, paradoxically, eating disorders usually lead to reduced sexual activity, so could they be freeing up girls’ time to do other things instead? One possibility is that they represent an unconscious strategy, usually successful, to delay puberty or halt menstruation. In the past, this may have been a sensible mechanism to avoid a potentially disastrous pregnancy during times of want – although self-starvation seems an unnecessarily risky way of achieving this. And today, girls face tremendous pressures not to get pregnant, to succeed in school, university and career, so it is certainly possible that these modern stresses now trigger those ancient female strategies for reproductive restraint.

Another reproduction-oriented theory relates to competition between women for male mates. Although this may not seem a very feminist idea, it is claimed that in societies in which women compete for male attention by appearing slim and youthful, some individuals may ‘over-compete’ by becoming extremely thin and losing the curves which come with maturity. Thus eating disorders could represent an abnormally exaggerated psychological response to prevailing body-shape ideals – some women get slim, but others go too far. And there is experimental evidence that women do indeed eat less after meeting women with high social status, even if those women are not themselves particularly slim.

The final evolutionary theory of eating disorders is perhaps the weirdest of all, because it has a bizarrely self-sacrificing flavour to it. The idea is that girls in high-status, mutually protective, families stop eating to free up resources for their siblings – and their brothers in particular. Because high-status boys have the potential to father more children than their sisters could mother, it is argued that sometimes the best way for a girl to pass on her genes is to support her brother in his attempts to sow his seed far and wide. After all, the arithmetic of inheritance dictates that siblings share approximately half their genes, so if a girl’s brother sires three children (which can be the work of just a few hours for him), then more of her genes will reach the next generation than if she rears a single child herself (which is the work of two decades for her). It may seem utterly perverse that girls should self-starve to add fuel to their brother’s promiscuity, but the genetic numbers would, in fact, add up in support of this theory.

All these evolutionary explanations of eating disorders sound, to be honest, weird. We are startled by the suggestion that women contain within them a genetic propensity to self-starve so they can cope with an erratic food supply, signal impending starvation to others, evade social conflict, avoid pregnancy, attract a mate, or encourage their brothers to sleep around. All these ideas have their weaknesses, and no single theory can explain every aspect of eating disorders. However, some of them probably contain shreds of truth, and none is mutually exclusive, so maybe those shreds have combined to underpin the eating disorders which blight so many women’s lives today. After all, there must be something which makes females of our species, and our species alone, prone to these debilitating conditions.

I would speculate that the sheer harshness of life during our evolutionary history has indeed left women with a complex set of inbuilt responses to famine and plenty. And those responses were helpful when we were hunter-gatherers, but do not fit well with modern life where food is not just abundant but over-abundant. Eating the right amount at the right time was truly a matter of life and death for women over much of the last few million years – consuming enough to allow them to carry out their roles in prehistoric societies, while deferring to the energy needs of calorie-guzzling men. So women evolved robust, almost stubborn strategies to cope with these horrendous pressures, and that stubbornness is evident today in the immense resistance to treatment of many eating disorders.

Those stubborn strategies are built into the vast human female brain as a complex network of neural reactions to food, mood and body shape, and like so many things in biology, those neural networks differ between women. There is no single best strategy, and different women cope in different ways. I believe that the neurologists are correct, and that some women possess quirks of brain circuitry which predispose them to eating disorders. But I also think the sociologists are correct too, and that the precipitating cause of anorexia and bulimia is usually the culturally imposed idea that thinness is good. And in the next chapter I will examine whether the relentless barrage of skinny images, thoughtless comments and makeover shows really does affect how women think about body shape.

If a woman has a genetic or neural predisposition towards eating disorders, then all it may take is a twinge of worry about her body shape and an apparently harmless, ‘well-intentioned’ diet to precipitate her slide into anorexia or bulimia. I would argue that women’s hyper-complex brains provide the vulnerability, and the cult of thinness provides the trigger.

Female body shape has a central importance in the workings of the female mind, and the interactions between the two are fiendishly complex and deeply ingrained. They explain so much about what it means to be a woman, living in a woman’s body, with a woman’s appetites, yet the body and the mind do not coexist in isolation. As we will see in the last part of this book, they cannot ignore the world outside.