The defences of Scapa Flow during World War II

On 3 September 1939 Britain declared war on Germany, and once again Scapa Flow became Britain’s main wartime naval base. That was when the War Office instituted ‘Plan Q’ – a blueprint for the wartime defence of Scapa Flow. It was a complex plan, calling for an integrated system of land, sea and air defence, and the creation of a base that was impenetrable to submarines, and well-enough defended to deter the Luftwaffe from even attempting to attack it. The anti-aircraft defences called for the emplacement of 80 heavy anti-aircraft (HAA) guns around the anchorage, supported by 40 light anti-aircraft (LAA) pieces. No fewer than 108 searchlights would be deployed, while 40 barrage balloons on land and on barges would deter low-level attacks directed at the main fleet anchorage.

First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill actually disapproved of the plan, as he thought British resources should not be wasted on passive defence which tied down three AA regiments in Orkney for the duration of the war. However, he immediately approved the dispatch of an extra 16 3.7in. HAA guns, to augment the eight belonging to 266 Battery that were already sited where they could protect the Lyness fuel tanks. Twenty more were earmarked to be sent north before the end of the year. In mid-September Churchill journeyed to Scapa Flow to see the defences for himself, and visited HMS Iron Duke, the floating headquarters of Admiral Sir Wilfred French, Admiral Commanding Orkney and Shetland (ACOS).

In mid-September 1939 the army assumed control of the Orkney defences, and on 29 September Brigadier-General (later Major-General) Geoffrey Kemp MC arrived in Orkney to assume command of the Orkney and Shetland Defences (OSDef). Apparently he wanted to set up his headquarters in Kirkwall, but the most suitable building – The Kirkwall Hotel – was already occupied by Vice Admiral Max Horton and his staff. Horton was in charge of the Northern Patrol, which performed the same function as had its predecessors in the last war. Consequently Kemp decided to set up his headquarters in the Stromness Hotel instead.

When he arrived he was a commander with very little to command. The forces at his disposal consisted of the five coastal defence guns at the nearby Ness Battery and on Flotta, 226 Battery with its eight 4.5in. HAA guns at Lyness, and three Bren guns guarding the newly installed radar station at Netherbutton in the East Mainland. Finally he had a company of the 5th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, at his disposal, and a field company of Royal Engineers. His force of little over 500 men had to defend hundreds of kilometres of Orkney coastline, as well as protect the fleet in Scapa Flow. His staff consisted of a clerk with a typewriter, and a driver with a car. He even had to borrow a civilian boat in order to visit his naval counterpart on board the Iron Duke, or to inspect the batteries on Flotta.

His arrival coincided with the first German reconnaissance flights over Scapa Flow, which encouraged him to press the War Office for reinforcements. He also began work on a defensive plan – a scheme that would soon blossom into something akin to ‘Plan Q’ drawn up shortly before the war began. His first task was to establish the locations of the most important gun batteries and searchlight positions, and to coordinate anti-aircraft defence with Admiral French. The result was his first Operational Instruction, issued on 10 October, which permitted the engaging of any air targets under 1,200m (4,000ft) flying within ten kilometres (six miles) of the Home Fleet flagship mooring on ‘A-Buoy’.

Within days Kemp received reinforcements – the rest of the 5th Battalion of Seaforths arrived, together with the 7th Battalion, Gordon Highlanders. He now commanded a brigade-sized force. The Gordons were ordered to take over the protection of vital points (VPs), which included the batteries on Flotta, the landward sides of the boom defences, as well as the telephone cable huts, wireless stations and radio masts that were sprouting around the Orkney landscape. Later that month two more field engineer companies arrived, which allowed Kemp to begin working on the construction of camps to house the labourers needed to put ‘Plan Q’ into effect.

Meanwhile the Admiralty were trying to play their part in improving Scapa Flow’s defences. In 1938 blockships had been sunk to seal off the gaps in the eastern channels of Scapa Flow. The largest of these was Kirk Sound, between the Orkney Mainland at Holm and the small island of Lamb Holm. Although the channel was blocked by World War I blockships there were gaps that allowed small vessels to weave their way past the obstructions. While efforts had been made to seal these channels before the war began, they still remained vulnerable. Admiral Forbes inspected them in person in June 1939, and deemed them to be navigable, regardless of the claims made by the Admiralty. More blockships were purchased, and in September and early October 1939 these were sunk in position. The last channel to be sealed was Kirk Sound, and the 4,000-ton steamer SS Lake Neuchatel was even in Scapa on the night of 14 October, waiting to be towed into place and scuttled.

That night U-47, commanded by Korvettenkapitän Günther Prien, passed through Kirk Sound, and penetrated the defences of Scapa Flow. Finding the main anchorage empty, Prien headed north, and spotted the battleship HMS Royal Oak lying beneath the cliffs of Gaitnip, a few kilometres from Scapa Pier. The U-boat fired a total of seven torpedoes at the battleship, hitting her with three of them. The Royal Oak sank in 13 minutes, taking 833 of her crew down with her. U-47 then slipped out of Scapa Flow the way she had come in – weaving her way past the blockships of Kirk Sound. The Lake Neuchatel was scuttled in Kirk Sound a week later, but by then the damage had already been done.

The increased threat posed by German aircraft meant that heavy and light AA batteries and searchlight positions now ringed the anchorage, while barrage balloons and rocket batteries deterred enemy pilots from making low-level sorties against the fleet.

The crew of a Lewis gun, photographed on the perimeter of the Royal Naval Air Station HMS Sparrowhawk, possibly during an air attack on Scapa Flow in early 1940. By the summer of 1940 Orkney was bristling with light and heavy anti-aircraft weapons, and these proved sufficient to deter any further larger German attacks. (Orkney Library & Archives)

The Royal Oak disaster caused an uproar. The Admiralty were rightly blamed for leaving Scapa Flow so poorly defended, but somehow Churchill weathered the political storm. The commander of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir Michael Forbes, declared that the anchorage was unsafe, a point which was reinforced three days after the disaster when Scapa Flow suffered its first air raid. He ordered the Home Fleet to disperse to other anchorages – the Firth of Forth and the Cromarty Firth on the North Sea coast of Scotland, and the Forth of Clyde and Loch Ewe on the west coast. Emergency meetings of the War Cabinet were held, while both the War Office and the Admiralty were forced to re-examine their plans. For his part Admiral Forbes remained convinced that Scapa Flow remained the best anchorage for the Home Fleet. All he asked was that it was properly protected.

The result was that an ‘Inter-Services Committee for the Defence of the Fleet Anchorage of Scapa Flow’ was hurriedly established in Whitehall, and a fairly lavish budget of £500,000 was approved for the construction of new defences, with more money available if it was needed. This time there would be no half measures. The result was ‘Plan R’. This called for the implementation of ‘Plan Q’, augmented with a much more extensive network of coastal batteries, anti-submarine defences, radar stations, airfields, minefields and anti-invasion defences. As a result Orkney was going to become a fortress – the most heavily defended harbour in Europe.

By December 1939 construction contracts had been signed, guns allocated and anti-submarine nets ordered. Merchant ships arrived carrying construction materials, as well as everything from searchlights to barrage balloons. The garrison was heavily reinforced, and the new gun positions chosen by the newly promoted Major-General Kemp were approved, and the foundations dug. Both the Fleet Air Arm and the Royal Air Force scoured Orkney for suitable sites for aerodromes, while anti-aircraft battery sites were chosen and the guns installed almost as soon as they could be unloaded. All this frenetic activity was taking place amid a particularly bad winter, where the gales, snow and rain seemed incessant.

In this striking photograph a carrier platoon from an infantry battalion of the Orkney Garrison (probably the 7th Bn., Gordon Highlanders) conduct manoeuvres through the middle of the Ring of Brodgar, a circular ‘henge’ of Neolithic standing stones, surrounded by a wide ditch. (Private collection)

Part of the reason for the haste was a deadline. As First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had forced the new Inter-Services Committee to declare that the Home Fleet would return to Scapa Flow on 1 March 1940. This was no arbitrary deadline. Instead it was based on the grim assessment that the dispersal of the fleet had weakened the ability of the Home Fleet to react to German naval movements. Intelligence suggested that the Germans might be planning a spring offensive, and Churchill wanted the fleet to be ready for action when the time came. This was the reason these construction workers dug foundations in the snow, or poured concrete in the teeth of a howling gale.

A Bofors 40mm light anti-aircraft gun, deployed on ‘The Citadel’ outside Stromness, overlooking the Ness Battery (pictured on the right of the photograph) and Hoy Sound, the westerly entrance into Scapa Flow. (Private collection)

Fortunately the Luftwaffe left the garrison to its own devices, although the occasional reconnaissance and mine-laying flight continued throughout that first winter of the war. By February the first phase of coastal battery construction had been completed, and most of the booms and anti-submarine defences had been put in place. The biggest weakness lay in the anti-aircraft defence of the anchorage, as the only guns that were operational were those of 266 Battery at Lyness. A further 20 HAA guns were in their battery emplacements, and their crews were just assuming their duties. Kemp pushed his superiors and his men, and by the end of the month these guns were all operational, as were another 11 HAA guns and 13 light AA guns, supported by 28 of the 100 searchlights allocated to OSDef.

In the end Churchill’s deadline was delayed by a week for operational reasons, by which time Kemp had increased his operational HAA complement to a healthy 52 guns. The targets set by ‘Plan Q’ were now well on their way to being met. On 8 March 1940 Churchill planned to enter Scapa Flow in style aboard HMS Rodney. However, a mine scare kept her at sea while the approaches to the anchorage were swept, so Churchill transferred to a destroyer, and made his entrance on board her. By that evening he was dining on board HMS Hood, which effectively sent the signal that Scapa Flow was safe, the fleet had returned and the Royal Navy was ready for action.

A German Junkers Ju 88 twin-engined bomber, photographed near the farm of Flotterston in Sandwick, on the West Mainland of Orkney. A Grumman Martlet from 804 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm, based at RNAS Skeabrae, shot her down on Christmas Day 1940. (Private collection)

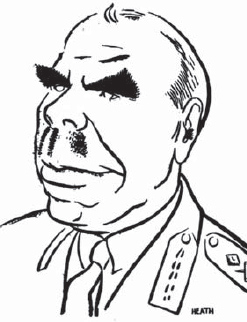

Major-General Geoffrey C. Kemp, an artillery veteran of World War I and holder of the Military Cross, was the first commander of OSDef (Orkney & Shetland Defence Force), arriving to take command of the garrison in September 1939. (Private collection)

On his return to Whitehall Churchill reported to the War Cabinet that Scapa Flow was ‘80% secure’, and the risk of attack on the fleet was acceptably low. It was during this visit that he approved the plan to build permanent anti-submarine barriers across the eastern channels leading into Scapa – the barriers which now bear his name. The deadline imposed by him, and the return of the fleet at that time, were both fortuitous. The first serious air raid on Scapa Flow was carried out by the Luftwaffe on the evening of 16 March, and increasingly heavy raids would follow in the weeks to come. Then, on 9 April, the Germans launched Operation Weserübung – their codename for the invasion of Denmark and Norway. The Home Fleet was ready and able to intervene, and consequently the German Navy (Kriegsmarine) suffered serious losses during the operation, even though the German Army (Heer) managed so secure control of both countries, despite Allied intervention.

This meant that by the time the campaign ended in June 1940, the Kriegsmarine could use the Norwegian fjords as operational bases, while the Luftwaffe airfields in Norway were now within easy striking range of Scapa Flow. However, no such raids ever materialized, although reconnaissance and minelaying sorties continued throughout the war. This way largely owing to improvements in the anti-aircraft defences of Scapa Flow – by mid-April 1940 there were 88 HAA guns deployed around Scapa Flow, which more than fulfilled the requirements of ‘Plan Q’. Major-General Kemp now commanded over 12,000 men, with two full brigades at his disposal. A hundred aircraft searchlights were in place, of which 88 were operational, and Orkney now boasted 14 coastal batteries, with most of the guns mounted in them ready for action.

More importantly, the fully integrated defensive system called for by ‘Plan R’ was now working, with these fixed defences capable of coordinating fire with the Royal Navy, while covering the complex network of booms, nets and mines that were now in place. The anti-aircraft defences of Orkney were provided with targeting information from several radar sites, which also helped fighter control direct their aircraft to intercept enemy planes. Of course there were setbacks – one day in April the RAF launched 40 barrage balloons around the anchorage – the full quantity specified in the two plans. A sudden gale then came from nowhere, and all but one of them were ripped from their tethers and lost. However, it was clear that by the summer of 1940 the defences of Scapa Flow were formidable. The Germans were well aware of their scale, which explains why they never attempted another attack against the anchorage, despite the proximity of their Norwegian bases. Orkney was now an impregnable fortress.

| Key: | |

|

Guard and mine loop (underwater) |

|

Indicator loop (underwater) |

|

Boom (on surface) |

|

ASW boom |

|

Coastal defence battery |

|

Barrage balloon site |

|

Water-borne barrage balloon |

|

AA battery (heavy) |

|

Searchlight station |

|

Rocket battery (AA) |

|

Naval signal station |

|

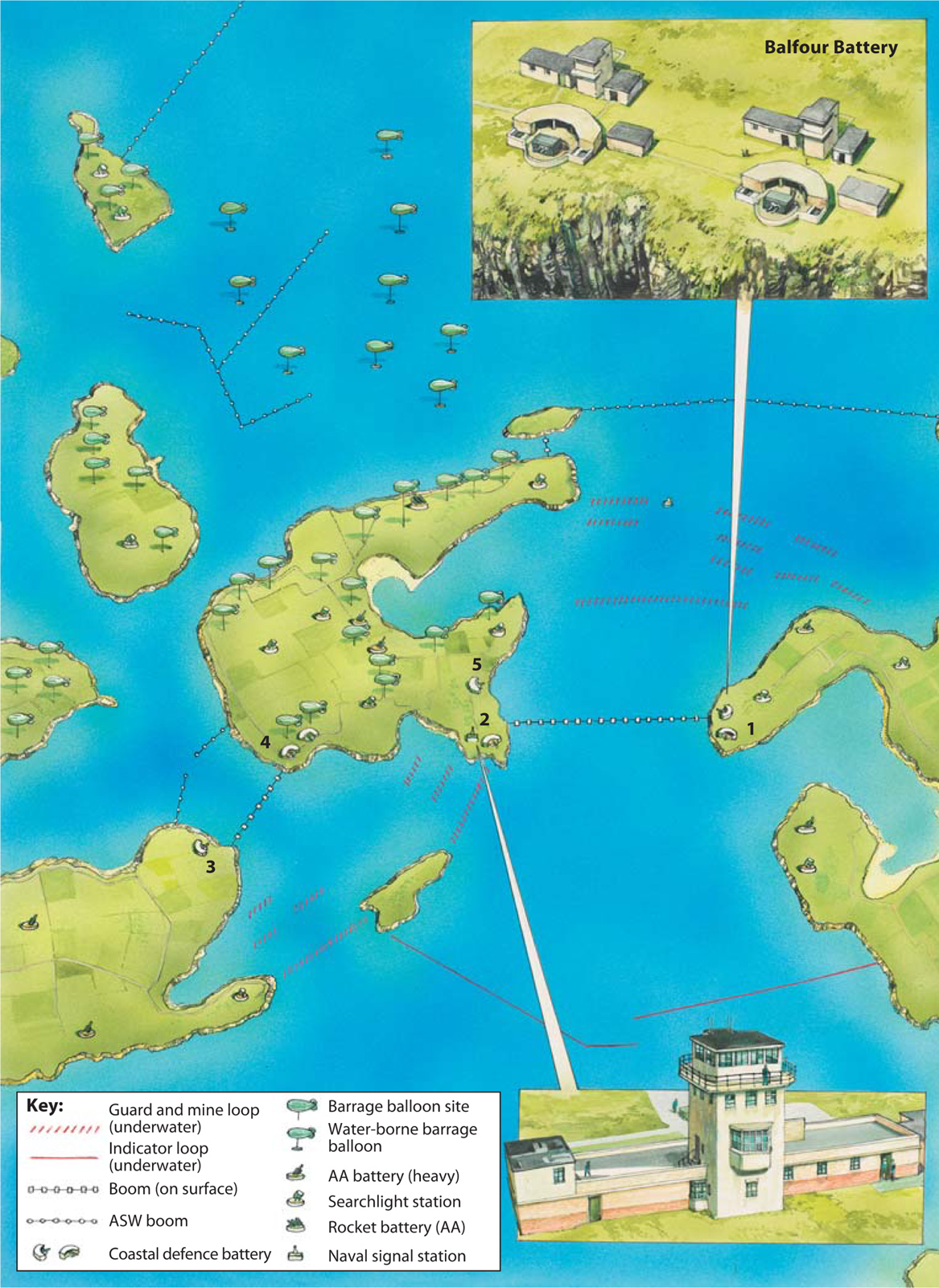

DEFENCE OF THE ANCHORAGE: HOXA SOUND, 1940 |

During World War II the main entrance into Scapa Flow was extremely well defended, against all forms of attack. First, gun batteries on Hoxa Head (1) Stanger Head (2), Walls (3) and Innan Neb (4) with its associated secondary Neb and Gate Battery, all secured Hoxa Sound and Switha Sound from attack by enemy surface ships. Additional light batteries – the Buchan Battery on Hoxa Head (5) and the Balfour Battery on Flotta (see inset) provided additional protection against E-boats or other fast attack craft. A control position on Stanger Head (see inset) provided a vantage point from which the defence of the entrance could be coordinated.

Searchlight and anti-aircraft positions dotted the area, while barrage balloons helped protect the main fleet anchorage from attack by low-flying enemy aircraft. Underwater protection was provided by a magnetic induction loop (thick red line), by controlled minefields (red slashes), and by anti-torpedo nets, which were also strung from barges in the main anchorage. Finally anti-shipping booms blocked Hoxa Sound and Switha Sound.