During World War I enemy U-boats posed the only real threat to Scapa Flow. Unfortunately, when the war began, the anti-submarine defences of the base were minimal consisting of a fishing net strung between buoys as a makeshift anti-submarine boom and lookouts searching for periscopes.

U-boats were spotted off Scapa Flow during these first months of the war, but it was only on 23 November 1914 that an attempt was made to penetrate the anchorage. Kapitänleutnant von Hennig in U-18 submerged in the Pentland Firth and entered Hoxa Sound. However, when he encountered the makeshift anti-submarine boom stretched between Roan Head and Hunda he decided to give up on the attempt. In truth he could probably have dived beneath it. The current disoriented him and he came to periscope depth off Hoxa Head, only to be rammed by a converted trawler. He subsequently ran aground on the Pentland Skerries, at which point he scuttled his boat.

The German press called the U-boat commander Korvettenkapitän Günther Prien the ‘Bull of Scapa Flow’ after U-47 penetrated the defences of the base in October 1939 and sank HMS Royal Oak. (Stratford Archive)

This was the last serious German attempt to penetrate the defences of Scapa Flow until the last weeks of the war. By that time the anti-submarine defences were formidable, and included induction loops, guard loops and controlled minefields. On 28 October 1918, Oberleutnant Emsmann in U-116 decided to enter Scapa Flow through Hoxa Sound. He hoped to sneak in beneath a British warship. However, at 8pm the hydrophone station on Stanger Head detected his approach. The defenders switched on the searchlights, and the guard loops. Then at 11.30pm Emsmann’s periscope was sighted at the entrance to Pan Hope, just south of Roan Head. That meant that the U-boat was almost on top of the controlled minefield. Minutes later the galvanometer in Roan Read flickered as the U-boat passed over the guard loop in front of the minefield. The order was given to activate the controlled minefield, which was then detonated. U-116 went down with all hands, leaving a twisted wreck on the seabed. She had the distinction of being the last U-boat casualty of the war, and the only one to be destroyed by a minefield controlled from the shore.

When World War II began in September 1939 Scapa Flow was almost as poorly defended as it had been in 1914, although this time at least anti-submarine booms were in place across the two main entrances. Blockships sealed off the small eastern channels, while more blockships were due to be scuttled to seal off these channels completely. That September the Luftwaffe conducted reconnaissance flights over the anchorage, and naval analysts discovered that one of these entrances – Kirk Sound – wasn’t completely sealed. It was just possible that a daring U-boat commander could thread his way through the blockships, and so penetrate the defences of Scapa Flow. The man chosen to make the attempt was Korvettenkapitän Günther Prien, who commanded U-47.

These sailors from the Royal Oak were photographed on board the drifter Daisy II on 13 October 1939, as they headed towards Scapa Pier to savour the delights of wartime Kirkwall. Two out of every three crewmen from the battleship were killed the following day. (Stratford Archive)

During a bombing raid on 16 March 1940 around 50 German bombs were released over this cluster of houses at the Brig of Waithe near Stromness. One of the cottages was hit, killing its occupant James Isbister. He was one of the first British civilian air raid casualties of the war. (Stratford Archive)

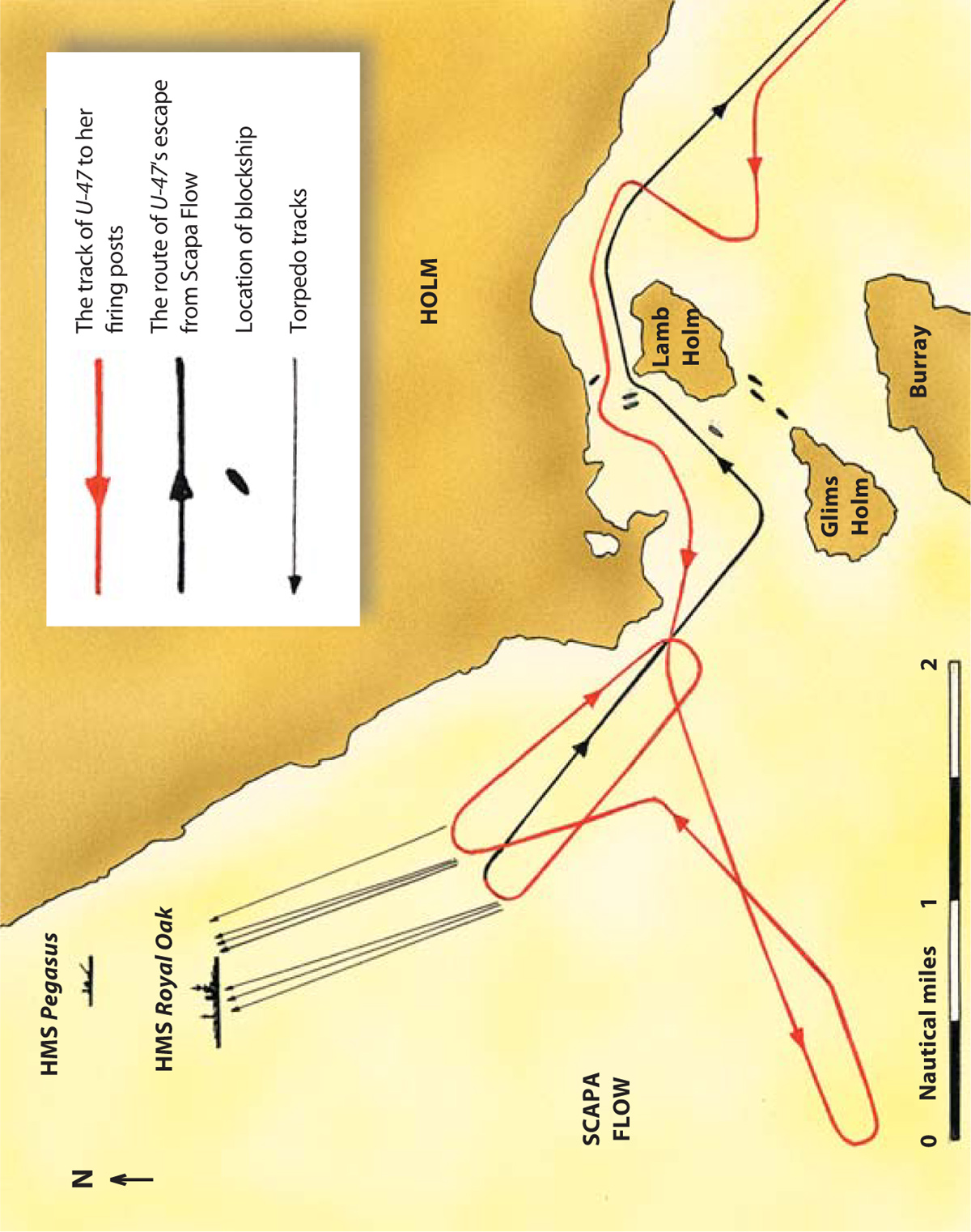

By the afternoon of 13 October 1939, U-47 was lying submerged off the eastern coast of Orkney as her commander waited for darkness to fall. This still wouldn’t provide much cover though, as it was an exceptionally clear night, and the aurora borealis (northern lights) lit up the sky. At 7.15pm the U-boat came to the surface, and Prien set a course for Kirk Sound. By 11.30pm he was in Holm Sound, with the high tide working in his favour, and he steered between the small island of Lamb Holm and the Mainland, evading the blockships set there to prevent just such a passage.

Prien then headed westwards towards the main anchorage but found it empty, the fleet having sailed the previous evening. He then turned northwards towards Scapa Bay and, shortly before 1am, he spotted a battleship lying just over a kilometre off the eastern shore. She was anchored off Gaitnip, where her anti-aircraft guns were able to cover Kirkwall in case the town was attacked. Prien approached the battleship from the south, until he was within 3,600m (4,000 yards) of his target. He fired four torpedoes, although one failed to launch. Although he didn’t score any hits, at 1.04am there was a small explosion forward, possibly from a torpedo striking the anchor cable. On board the battleship – HMS Royal Oak – it was thought that the explosion was an internal one, from one of the forward inflammable materials store. While the captain and the duty watch investigated, the rest of the battleship’s crew went back to sleep.

Meanwhile Prien had turned his U-boat around and fired one of his two stern tubes. Once again the torpedo missed. Prien calmly steamed away to the south, then reversed course once the bow tubes had been reloaded. At 1.15pm he fired three more torpedoes. This time there were no mistakes, and two or three of them hit the starboard side of the battleship. A survivor described what happened: ‘Then, just 13 minutes after the first explosion, came three more sickening, shattering thuds abaft us on the starboard side. Each explosion rocked the ship alarmingly, all lights went out, and she at once took on a list of about 25°.’ Eight minutes later the battleship rolled over and sank, taking 833 men down with her.

Prien steered U-47 back towards Kirk Sound at full speed, leaving the anchorage in an uproar. Prien and U-47 returned safely to a hero’s welcome in Germany.

If anything good came of the tragedy it was that the War Office and the Admiralty finally realized that Scapa Flow’s defences were inadequate, a point which was reinforced just four days after the Royal Oak disaster, when the first air attack was launched against the fleet in Scapa Flow.

|

SCAPA FLOW: THE SINKING OF THE ROYAL OAK |

The spread of three torpedoes which sank HMS Royal Oak were fired at 1.13hrs, at a range of a little over 3,000m (3,300 yards). At that distance the torpedoes took almost three minutes to reach their target. On board U-47 two or possibly three explosions were recorded at 1.15hrs, and a blinding light illuminated the British battleship, followed a few seconds water by a shock wave. A column of fire rose and then vanished, to be replaced by a plume of smoke. Before Korvettenkapitan Prien gave the orders to turn away and begin the U-boat’s escape from Scapa Flow, he saw that the Royal Oak was listing heavily, and was obviously sinking. Two nautical miles beyond her lay another ship – the seaplane tender HMS Pegasus – and signal lamps began flashing on board her, presumably reporting the attack to other warships in the anchorage. During Prien’s exit from Scapa Flow, he evaded a destroyer and searchlights to make good his escape. By 2.15hrs U-47 had reached the comparative safety of the open sea.

The remains of the blockship SS Reginald lie beside Barrier No. 3, between Glims Holm and Burray. The Clyde-built motor schooner was scuttled in 1915. The wreck is now used as a convenient shelter for Burray lobster fishermen. (Author’s collection)

At dawn on 17 October 1939 four Ju 88 medium bombers attacked the battleship HMS Iron Duke, which was anchored off Lyness. She was then serving as the floating base headquarters. She was damaged and was towed onto a nearby sandbank, to prevent her from sinking. She remained beached for the rest of the war.

That afternoon the bombers returned, but no ships were hit, although one bomb exploded near the oil tanks of Lyness – the first bomb to land on British soil. The fleet promptly withdrew to safer bases. In the months that followed the Orkney defences were strengthened, until in March 1940 it was deemed a secure anchorage, and the Home Fleet returned to Scapa. Amongst the other improvements was the provision of anti-aircraft guns, as Scapa Flow was vulnerable to air attack. These air defences were put to the test within weeks of the fleet’s return.

At dusk on 16 March about 15 German medium bombers attacked two targets – the warships at anchor in Scapa Flow, and the new Fleet Air Arm airfield at Hatston, near Kirkwall. The cruiser HMS Norfolk was holed by a near miss and nine of her crew were killed. This was the raid that resulted in Orkney’s first civilian casualty, killed by a cluster of bombs that were dropped near the Brig of Waithe near Stromness. This raid highlighted problems with the coordination of anti-aircraft fire, and the lack of warning provided by radar. The result was the development of the ‘Scapa Barrage’, a defensive wall of flak designed to keep attacking aircraft away from the main anchorage.

The Luftwaffe returned on 8 April, when 24 medium bombers (a mixture of Ju 88s and Heinkel He IIIs) attacked the booms and other defences of Hoxa Sound. No hits were scored, but it was claimed that seven German bombers were shot down. This time the British had ample warning of the attack, as the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Curlew used her radar to detect the enemy before they reached Orkney.

This raid was timed as a distraction, covering the German invasion of Denmark and Norway. Another raid was expected, and this materialized at dusk on 10 April, when 60 German Ju 88s and He IIIs attacked in two waves, one from the east, the other from the south-east. Both waves approached at just under 3,000m (10,000ft), but were met by the full force of the ‘Scapa Barrage’. Only one wave of 20 aircraft penetrated the wall of flak, and once again their bombs were aimed at the Hoxa Boom defences. No hits were scored, although the heavy cruiser HMS Suffolk suffered minor damage. At least five of the attacking aircraft were shot down, although intelligence later reported that several damaged German aircraft never made it back to their bases.

That was the last major air attack on Scapa Flow, as the Germans had realized that the air defences around Scapa Flow were now too strong to make another large-scale attack viable. However, a half-hearted raid on 24 April tried to probe its way around the barrage, with only five aircraft actually penetrating the defences to reach Scapa Flow itself. No hits were scored. From that point on the Germans limited themselves to mine-laying and reconnaissance missions, and even these were considered dangerous as the radar defences and fighter cover around Orkney meant that these operations were costly. The Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine never repeated these early war attacks as, rightly enough, they considered an attack on Scapa Flow to be a near-suicidal proposition. Consequently the Home Fleet now had a refuge that was safe from German attack. While it mightn’t have seemed like it at the time, the men of the Orkney garrison played a vital strategic role that helped ensure the containment and ultimately the defeat of Nazi Germany. The provision of this all-important safe haven for the Royal Navy was the ultimate achievement of the Scapa Flow defences.