“As a gambler,” John Aspinall said a year after John Lucan disappeared, “I would give even odds on whether he is dead or alive.” Whole books have been written on sightings of Lord Lucan, and in many ways, that story has almost eclipsed the events of the night of November 7, 1974. It has certainly wiped the death of Sandra Rivett from the public’s memory.

The police description of John Lucan as circulated in the days after the murder and attempted murder shows him as 6 feet 2 inches tall. His complexion is described as “ruddy”; his hair is brown and his moustache is brown flecked with ginger. His eyes are blue and he has gold fillings in his teeth. He was last seen (by Susan Maxwell-Scott) wearing a light-colored sweater and dark-colored trousers. His habits? He smokes Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes, drinks vodka, attends race meetings, gambling clubs and, perhaps unhelpfully, “may travel abroad.”

Looking at the familiar photographs of the man, reproduced in every book on the case, we can add that his hair is parted on the left and slicked down with Brylcreem. His heavy eyebrows nearly meet over the bridge of his nose—an English old wives’ tale is that men with this facial characteristic are born to hang! The photos of Lucan’s engagement and wedding in 1963 show a slim man of thirty-one. By the time of Sandra’s murder, he was over 40 and beginning to put on weight.

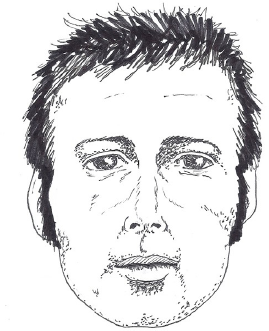

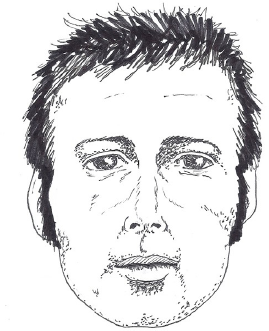

Imaginative sketch of Lord Lucan on the run after the murder

Now take away the moustache. Comb the hair in a different way or bleach it. Stoop slightly. Do what you can with the cut-glass English accent. Do that and anyone reading this account may have walked past John Lucan on any day in the last 37 years and not noticed him at all.

More difficult to arrange than mere physical appearance, however, is survival over that period. Lucan left his flat in Elizabeth St., Belgravia, without his passport, his checkbook or his driver’s license. He didn’t have much money because of his gambling debts, but even so, the various bank accounts he owned have remained untouched. His initial problem would have been to get out of the country.

If the obvious conclusions are drawn from the car abandoned at Newhaven, Lucan took the cross-Channel ferry to Cherbourg or St. Malo and somehow slipped past customs officials by slick movements or bribery. From there, he could have gone literally anywhere in the world.

Alternatively, we know he owned a speedboat, the White Migrant, in the 1960s, because it sank spectacularly in an offshore power-boat race off the Isle of Wight near England’s south coast. Could he have had a similar boat moored at Newhaven, perhaps under an assumed name or at the River Hamble nearby? If he did, then he’d be able to cross the Channel himself and come ashore anywhere on the European coast, most likely France, Spain or Holland. However, there is no record of any such boat; neither did one go missing in the days following the murder.

What about flight? A careful police watch was mounted on all ports and airports, but was it set up quickly enough? Lucan would have been able to get to any of London’s airports before Ranson and his team could put out an all-points bulletin for him. We still have the problem of the passport, but if Lucan had a second one, which he took with him, that would pose no problem at all. Why risk an airport with all its red tape and official snoopers when Lucan’s friend, the racing driver Graham Hill, had his own biplane that could have dropped Lucan at, say, a French airfield within an hour of his leaving London?

If he left the country by other means, how did the Corsair get to Newhaven? Roy Ranson was of the opinion that someone else drove it there, which explains the time lag between Lucan leaving the Maxwell-Scotts’ and the earliest time the car could have been parked on the coast.

The police began to get calls from all over. The calls started in November 1974 and are still going on today. A friend of mine was told by a retired Met officer in 2004 that they knew exactly where Lucan was—his body lay in a cave in Sussex, not far from Newhaven where the Corsair was found. Cranks of all sorts came forward with theories. Mediums, clairvoyants, even water dowsers all claimed to be able to pinpoint the position of the missing earl. He was sailing on cruise ships, like some sort of latter-day Flying Dutchman, never able to get off anywhere for fear of being recognized. He was operating roulette and backgammon tables in Monte Carlo. He was holed up in friends’ farms in South Africa, deep in the bush (Ray Ranson actually spent weeks there trying to track him down). He was with the drug lords in Colombia, South America. He was working as a double for Saddam Hussein!

One sighting that proved fascinating was that of an Englishman found in Australia. An Australian cop thought he looked like Ranson’s and Interpol’s circulated photographs of Lucan, so he arrested the man. He was certainly English. He was the ex-Cabinet Minister John Stonehouse, who had faked his own suicide months earlier by abandoning his clothes on an Australian beach. Why? Because back home, he was wanted on fraud charges.

It seems unfair to single out one book that got it badly wrong, but it does illustrate a point. Ex-undercover cop Duncan Maclaughlin believed he had tracked Lucan down in the remote and inaccessible jungles of Goa, India. The man known as Jungle Barry was dead by the time Maclaughlin got there (in 2002), but when he showed photographs of Lucan to people who had known Barry, they all swore they were one and the same man. The book is well-written, and Maclaughlin worked hard and honestly to prove his case, comparing photographs, dates and places. He came to the conclusion that Jungle Barry, a backgammon player of formidable talent and with an ear for music, was indeed Lucky Lucan. His body had been cremated, so there was no possibility of knowing for sure.

When Dead Lucky—Lord Lucan: The Final Truth was published and serialized in a British newspaper, a radio celebrity and musician called Mike Harding spoiled the party. Jungle Barry was Barry Halpin, a Liverpool banjo player who had gone to Goa in a quest for spiritual enlightenment in the 1970s and had never come back.

Rather like Lord Lucan.

www.crimescape.com