See-Saw, Margery Daw,

Jack shall have a new master;

And he shall have but a penny a day,

Because he can’t work any faster.

See-saw, Margery Daw,

Sold her bed and lay on straw;

Was not she a dirty slut

To sell her bed and lie in the dirt?

Traditional1

In a playground near you, children playing on the see-saw are singing a song. It lilts from fifth to major third, as the frame tips up and down: See-Saw, Margery Daw. They’ll only sing the first verse, and they’ll sing the words like a mantra, devoid of meaning but full of pleasant mouthy sounds, as they push one another off the ground. The second verse of their song has been expunged from memory. It’s not unlike the way most children, and most of us living in cities, come to understand the countryside. If ever we think of fields, our thoughts about the countryside are benign, passive and vapid. To become and remain an idyll, the rural is forgotten, sanitized and shorn of meaning to fit the view from the city. For our purposes, airbrushing the countryside serves us badly. To understand the constraints on how food gets to us, we need to see agriculture’s collateral damage, and the ways in which the food system is already being imagined and built differently.

The city, now home of the majority of the world’s people, writes the country.2 But the country writes back, and always has. Let’s take an example, one of many that we could choose, but one we might pick for its pervasiveness, its grip on the collective imagination. Consider India.3 India fought for, and won, independence from colonial rule in 1947, and since then has been busy trying to write its own rags-to-riches story. At one level, it has succeeded. Today, India is, in the imagination of many outside the country, the place where all the jobs have flown, a Neverland of highly skilled workers willing to toil for very little. The new maharajahs of the IT industry routinely trumpet the industry’s growth rate (19 per cent per year between 2004 and 2008)4 and hail the pool of talent created by the government’s investment in education. Much has been banked on this myth. India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government even marched into the 2004 elections, with campaign literature depicting smiling fair-skinned Indians, triumphing over adversity, under the slogan ‘Shining India’. The BJP lost the elections.

Yet, in parts, there’s some truth to the ‘Shining India’ rhetoric. Go for a stroll anywhere within a couple of miles of the major city airports in Hyderabad and Bangalore, and you’ll see a great deal of shining. Oracle, Microsoft, Novell, Intel, IBM and Infosys all have sparkling new office blocks, glinting in the smogged sun. Hyderabad, the capital of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, is a town on the move. The corridors through which money flows – from airport to business park to government headquarters – have been polished so brightly they are unrecognizable to the city’s older residents. At night, the young people from the back offices come out to unwind in a parade of tight jeans and scooters, women with boyishly short hair driving their own 200cc scooters from call centre to coffee bar.5 This is progress of a kind. Yet even within the city, it doesn’t hold true everywhere: a third of the city’s six million residents live in slums, drawn to the city in hope of a better life, and with vanishingly little hope of ever joining the ranks of the tertiary-educated elite.6

If the narratives of urban progress camouflage poverty in the city, the tales told of rural India obliterate the very idea that suffering might be possible (unless it’s the redemptive kind). Just as the United States has its heart-warming tales from ‘the heartland’, and England’s Albion is always rural, India has sentimental narratives of ‘Mother India’. In these stories, the nation was born in the fields, and the proud modern state, now more urban than rural, is the offspring of the countryside. Reality is rather at odds with these homely national fictions of bucolic bliss. To take some scattered examples: in the US, more drug-related killings happen in rural America than in its cities; in the UK, more young people kill themselves in rural areas than in the cities. And India’s stories of progress and homeliness come undone in the fields too.

Five hours out of Hyderabad, far from the money and the glitter and the bandwidth, in India’s fields, it’s still possible to find women with short hair. Shaven-headed children too. Parvathi Masaya7 has a cropped cut quite different from the hair of other women in the village when I meet her on a hot, late monsoon day. I’ve pulled her away from her job making disposable plates from leaves. The younger of her two sons, a six-year-old, scrunches and unscrunches her sari in his hands while she talks. The eight-year-old is in a nearby classroom – joining in a chorus of reading from a blackboard.

Parvathi’s day is long. It begins at 5 a.m., when she prepares food for her sons and does some housework – washing, cleaning clothes, fetching water. The children need to be in school by 8.30, and she drops them off before heading to the plate ‘workshop’, outside a neighbour’s house. At 6.30 p.m. she returns, picks up her children from a neighbour, and goes to bed between 10 and 11. The plate-making pays badly – 25 rupees (US$0.50, GB£ 0.30) per day. It’s not enough for her to bring her children up on. ‘I used to put chillies in the rice to make it last longer, but then the boys fell sick. Now, my parents help me with a little money.’ Parvathi has her own land, four acres of it. It lies fallow at the moment. ‘I’m waiting for my boys to finish school. In maybe four years [when her eldest son, Chandramouli, reaches twelve], he’ll be able to work in the field. I can’t go into the city by myself [where wages might be higher]. Who would look after the children? So I’ll make plates. And we’ll survive.’

She doesn’t blame anyone for what happened: ‘I am not angry – what would be the point? If I were angry, I would not come back.’

At its peak, her family earned 12,000 rupees per year – less than US$0.75 (GB£0.40) per day – through farming. That’s when her husband, Kistaiah, was alive. On 11 August 2004, Kistaiah looked up at the cloudless sky and despaired. He had been sinking deeper and deeper in debt since 2000. He’d borrowed money because the rains had become erratic, and the groundwater had disappeared. Trying to grow rice, he had taken out loans to drill for water, initially borrowing Rs8,000 (US$180, GB£90) from a local bank, and then borrowing Rs90,000 (US$2,000, GB£1,000) from what Parvathi calls ‘a neighbour’ – the local money-lender. He’d sunk three holes across his land, and none had struck groundwater. And, by the second week in August, the rains still hadn’t come. His crops were dying in the fields.

That night, after everyone had gone to bed, Kistaiah got up and pulled down a small plastic packet from the shelf, a cheery green and white print bag, a little like the Indian flag, but with a band of pictures of perfect vegetables at the bottom of the packet and, instead of the cartwheel in the middle, a red and white diamond marked ‘poison’. He filled a cup with the granules, dissolved as much as he could with water and drank it. Then he lay down next to Parvathi.

The pesticide was an organophosphate called ‘phorate’, classified as highly hazardous by the World Health Organization and so toxic that the Food and Agriculture Organization sees no way it can safely be used.8 It is, however, widely available in India, with farmers in Andhra Pradesh consuming 35 per cent of the national total.9 It entered Kistaiah’s body while he was still mixing it, passing through his skin and lungs even before it reached his lips. It jammed the receptors in his nerves. His respiratory muscles became paralysed. He likely slipped into a coma before succumbing to asphyxia. He can’t have convulsed very hard. He died without waking his wife or two sons.

Parvathi shaved her hair off on 12 August 2004 in a ritual of grief.

Kistaiah was well liked by everyone in the village. ‘He was a bit quiet, a good farmer, and a good man,’ says Narasimha Venkatesh, the village representative. Kistaiah is mourned. But he was not alone. Authoritative figures are difficult to come by at a national level, but the state of Andhra Pradesh, with a population of seventy-five million, has been recording rural suicide rates in the thousands per year.10 Nor is this a problem limited to Andhra Pradesh. The hinterland of Mumbai, where the city finds its food,11 has experienced rocketing rates of farmer suicide. It’s a problem that has even hit India’s breadbasket. In Punjab, the epicentre of the country’s high-tech agricultural ‘Green Revolution’, the United Nations scandalized the government when it announced that, in 1995–6, over a third of farmers faced ‘ruin and a crisis of existence … This phenomenon started during the second half of the 1980s and gathered momentum during the 1990s.’12 It has been getting worse. According to the most recent figures, suicide rates in Punjab are soaring.13 As one newspaper put it, this sad end to the farmers who were meant to have thrived under India’s brave new agricultural future is a ‘Green Revocation’.14

Not all poor farmers kill themselves in India, of course. Rather than suicide, some farmers have sold their kidneys. In Shingnapur, a village in the Amravati district of Maharashtra, farmers have gone one step further, setting up a ‘Kidney Sale Centre’. ‘We … invited the Prime Minister and the President to inaugurate this kidney shop … Our kidneys are all we have left to sell,’ said one farmer.15

Shingnapur isn’t alone. Many villagers have simply put themselves up for sale – bodies and all. Within villages, too, there is inequality. Beyond the pervasive inequality between men and women, there is a key difference between those who still own farm land and those who have nothing left to sell but their labour. While farmers are more likely to die by their own hands, landless families systematically face the threat of starvation.

One might want to explain the despair that precipitates suicide as part of some idiosyncrasy, as a failure of the Indian government. Yet across the sea, in Sri Lanka, there’s a similar story. Averaged out over the country, pesticide poisoning was the sixth biggest cause of death in Sri Lankan hospitals, but within six rural districts, with a population of 2.7 million people, it was the leading cause of death in hospitals.16

East Asia is experiencing similar trauma. In China, ‘58 per cent of suicides were caused by ingesting pesticide’, and there are two million attempts per year.17 Of a sample of 882 suicides in China from 1996 to 2000, wage-earners and students comprised 16.9 per cent, homemakers, retirees and the unemployed comprised a quarter, but agricultural labourers made up over half of the dead. They were also the people most likely to die by other injuries.18 And rural suicide rates are triple those in urban areas, with women slightly more likely to kill themselves than men.19

We can also see an increase in some of these suicides in rich countries, not just poor ones. In Australia, the most acute rises in rates have happened in rural areas.20 In the UK, farming has the highest suicide rate of any profession.21 A spokesperson for the National Farmers Union put it this way: ‘There is not a farmer in the country that cannot name at least one friend, associate or colleague from within the industry who has taken his life because of the concerns they have for the future.’22

In the US, during the 1980s farm crisis, the Midwest suffered a spate of suicides. Commenting at the time, Glenn Wallace, regional programme manager for the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health, spoke of feelings that would be all too familiar to farmers in the Global South today: ‘the loss of a farm or the impending failure is worse for many farmers than the death of a loved one. The feeling of guilt that a family has when the sheriff’s-sale sign goes up on the place a great-grandfather homesteaded is more than they can bear.’23 National statistics are hard to come by and, strikingly, conclusive studies are yet to be conducted.24 But although Midwestern suicides seem to have peaked between 1982 and 1984, a number of other features have remained constant.25 Women, for instance, bear a triple burden, working both on and off the farm to supplement low incomes, as well as returning from paid work to take care of the home and participate in community activities. At least 25 per cent of US farmwomen find themselves in this position.26 At the same time, rural America has become disproportionately poorer. In 1999, only one of the fifty poorest counties in the US was metropolitan, and while the drug-related homicide rate has fallen in urban areas over the past decade, it has tripled in rural areas.27 While the acute symptoms of rural distress may have been dulled, its chronic features continue to plague the world’s richest country.

When suicides are recounted – and they seldom are – the death finishes the tale with the finality of the full stop at the end of this sentence. But the lives of families continue, and communities survive. These are not only individual tragedies, but social ones. If we look at them from the perspective of society, farmer suicides cease to be full stops at the end of a life. They become tragic ellipses in the struggle of a community. Within rural areas, there’s mounting evidence to suggest that the burden of this tragedy is borne unequally. Women carry its brunt. In one district in Southern India, for instance, a study found that the suicide rate for young men was 58 per 100,000. For young women it was 148 per 100,000.28 As a yardstick, the rate in the UK is less than 5 per 100,000.29 Rather than understanding farmer suicides as a series of awful vignettes, then, it makes more sense to see them within a more complex and tragic tapestry. They’re an acute symptom of a chronic malaise in India’s rural areas.

Mangana Chander, a strong and outspoken woman classed in the Indian government’s typology as ‘tribal’, lives in the village of Nerellakol Tanda (‘place where water always flows’).30 Two hours out of Hyderabad, its twenty-seven households have unusually small amounts of land, their tenure at the whim of the local landlord. They don’t earn enough from their land to eat. So they do what increasing numbers of rural families do – they migrate. ‘We women, fifteen of us, go to Hyderabad at a time, to do construction,’ says Mangana. ‘Women get Rs80 per day, men get Rs90–100 per day. There’s a place where you sit waiting for work. If there’s a big house being built, then they come and get you. If there’s no work, we don’t eat. It doesn’t happen often that we work continuously. So each month is ten days in the city, fifteen in the fields, and five days’ rest.’ Mangana is lucky. She borrowed just a little – Rs2,000 (US$45, GB£23) a year ago, which has been compounded by the moneylender to a debt closer to Rs3,000 (US$68, GB£35) now. Her children are in school. She thinks they might have a chance for a better life than her. But she’s not certain. ‘The people in the city need to understand how hard we fight to survive.’

Women surviving under these conditions, especially after the death of a partner, are fighting hard. Sometimes, the extended family can help out, as in Parvathi’s case, by sending along a few extra rupees to keep the children fed. In some cases, they can compound the disaster, handing the family land over to the dead husband’s brother, treating the wife and children like slaves. In some states, the government offers compensation if it can be proved that certain conditions are met – forty criteria in some provinces.31 In some cases, the village headman refuses to certify the death as a suicide unless he gets a taste of the compensation. When families get debt relief, creditors are paid off. But the debt is never forgiven. Even after the government hand-out, rarely is there enough money to put the family back onto any sort of secure long-term footing. So mothers are pushed by many prongs to the cities, to become domestic workers, construction workers and sometimes sex workers.

If the suicides and women’s struggles have been written out of the story it is in part because their existence has also been whittled away. Officially, they can’t possibly be suffering because, according to the government, the number of poor people in India has been falling. Farmers, and women farmers above all, are India’s poorest people. Part of the telling of the fairy tale of ‘Shining India’ demands that the poor disappear. In India, this has been achieved through the waving of a magical, statistical wand.

A tireless scholar and award-winning journalist of rural India, P. Sainath, has tracked how the rural poor in India have become works of creative fiction. In the early 1990s, for instance, the Indian government commissioned a team of experts to put together a method of finding out the country’s exact total of poor people. After a methodological review, investigation, debate and deliberation, the panel announced that two in five Indians were poor. The Indian government reacted as most governments, North and South, have tended to do: they found a panel of experts willing to certify that the number was substantially lower. Using outmoded methods, the government announced not that two in five Indians were poor, but rather that the number was less than one in five. That said, ‘less than nine months before it found a fall in poverty in the country [the Indian government] … presented a document [at an international donor conference in Copenhagen] saying 39.9 per cent of Indians were below the poverty line. It was, after all, begging for money from donors. The more the poor, the more the money.’32

Economist Utsa Patnaik has followed the statistical sleights of hand that have enabled India’s poor to vanish since the 1970s, and she has calibrated her observations by going back to one of the central features we associate with poverty – hunger. At the beginning of the 1970s, over half the population was classed as poor. Two decades later, in 1993–4, the number of poor people had fallen to just over one-third. This progress was achieved in no small part because the official threshold for poverty had been lowered. In the 1970s, being on the poverty line afforded you 2,400 calories per day – in the early 1990s, you were afforded only 1,970 calories per day. By 1999–2000, just over a quarter were poor – an impressive reduction. But the threshold for poverty meant consuming fewer than 1,890 calories per day. Says Patnaik, ‘by the 60th Round, 2004–05 [the poverty line] is likely to be below 1,800 calories and correspond to less than one-fifth of rural population’.33 Today, when the official figure for poverty in India is around 27 per cent, a more accurate calculation based on the implied calorie norm of 2,400 per day puts three-quarters of the population under the poverty line.34 To put it slightly differently, around half a billion people have been written out of poverty, by the simple expedient of shifting the goalposts and the diligent advertising of present and future prosperity. This is how the story of ‘Shining India’ is told – with an official narrative about poverty that directly contradicts the facts. Jobs have been created for the educated middle class, but for those without access to education the story has been rather different.

A man can hold land if he can just eat and pay taxes; he can do that.

Yes, he can do that until his crops fail one day and he has to borrow money from the bank.

But – you see, a bank or a company can’t do that, because those creatures don’t breathe air, don’t eat side-meat. They breathe profits; they eat the interest on the money. If they don’t get it, they die the way you die without air, without side-meat. It is a sad thing, but it is so. It is just so.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath35

A rule, as true in the United States as in India, is this: farmers who kill themselves have been scythed by debt. S. S. Gill, a professor of economics at Punjabi University who has studied the phenomenon in India, even has a prediction: ‘Show me a farmer with five acres, and 150,000 rupees (US$3,400, GB£1,800) in debt; I will say to you he is sure to commit suicide in the future.’ In Andhra Pradesh, for instance, 82 per cent of farmers are in debt. The main reason they take their first loan is to invest in the land and crops (although, like everyone else, they also borrow for other reasons, like paying for weddings or health care). Debt has its origins in the entrepreneurial impulse. Urged towards cash crops by the government (and, as we shall see, the large seed companies), farmers adopt plants that they can buy and sell in the market: cotton and groundnut, and to a lesser extent rice and sugar cane.

In India, before free market reforms, the government offered a minimum support price for crops so that farmers could know in advance what sort of returns they’d get, all being well in the fields. If all was not well in the fields, there was a system of support payments, and a Public Distribution System for produce that would provide cheap and wholesome food for all who needed it. Although the free market was allowed to operate to some degree, the government would provide support for infrastructure, and the irrigation that the new crops needed, and outreach services in order to provide research for farmers, and information for them on new seeds, techniques and crops. It was a blend of free market and government assistance.

At the beginning of the 1990s, this bundle of supports for the rural poor started to be untied. Under the banners of reform and liberalization, the government began to dismantle its imperfect but vital public assistance systems for farmers, so that they could be exposed to the harsh but improving, and now untrammelled, disciplines of the free market.36 Unfortunately, the free market neither supported nor redistributed to farmers who fell on hard times. Offering lower prices and fewer supports than the previous social arrangement, the freer market in agricultural goods presided over a split between rural and urban incomes. Every support that farmers had come to rely on was systematically pulled away, and the farmers fell. At the same time, as the state of Andhra Pradesh’s own Commission on Farmers’ Welfare noted, urban areas attracted foreign investment and glass towers.37 The result was that the rural hinterland’s income was unhitched from the city, and in the decade after 1993, rural income fell by about 20 per cent while urban income increased by 40 per cent.

There’s an important point to consider here. Perhaps all is going to be well in the long run. Perhaps the divergence between urban and rural income, unfortunate though it may be, is just a bump in the road. Perhaps the increasing levels of inequality that we see around the world are transient. There’s an economic thought experiment that predicts this, and which is important to understand. Imagine you’ve got two places and a population spread between them. Let’s call these places the country and the city. In the city, wages are high, but at the start of our thought experiment, there are very few people living there. By contrast, in the country, wages are low, and the majority of people are there. Inequality is low, because almost everyone’s earning the same low wage.

Now imagine that people drift to the city. When half the population is in the city and half in the country, as we have in the world at the moment, you’d expect inequality to soar, as it has over the past few decades. That’s just a mathematical fact. If the wages in one place are low and in another place are high, and if there’s an even split between the two, then of course there’s going to be inequality. In the future, we might imagine that everyone will move to the city, and live on high wages. Inequality will be low and, what’s more, wages will be high for everyone. There are, in other words, reasons to think that we don’t have to worry about inequality because, in the long run, it’ll come out in the wash. This is a logic which postpones worries about inequality, as levels of inequality increase worldwide.38

Two problems, though. First, the data in Andhra Pradesh show not just rising inequality, but increasing rural poverty. Rural communities are worse off in both relative and absolute terms. And, second, it’s far from clear that the people from rural areas are actually the ones benefiting from higher wages. Although the pull of the city may involve the promise of a higher standard of living, no-one is there to make sure the promise is kept. But, as Utsa Patnaik cautions us,

Let no-one imagine that unemployed rural workers are migrating and finding employment in industry: there have also been massive job losses in manufacturing during the reform period and the share of the secondary sector in GDP has fallen from 29 to around 22 per cent during the nineties, in short India has seen de-industrialization.39

In other words, the vaunted ‘Shining India’ has seen not only rural decimation, but also a progressive fall in the level of blue-collar jobs. These are jobs in which one might have expected India to excel, with its low wage rates. But no. India has skipped past industrial development, to become a software giant, a knowledge economy in which one third of the population is illiterate.

I was speaking to Sheshar Reddy, a leader of a farmer movement in Karnataka, about crop prices, when he learned I was interested in farmer suicides. ‘My son committed suicide,’ he said. ‘He was good-natured fellow. He was always helping other people with our tractor. But I think he was worried about not being able to get married. I’m not sure. One day he went to the clinic because he had some sickness. I don’t know why he killed himself. But he committed suicide that day.’ You’d have to listen very hard to pick up the very faintest warble in Reddy’s voice. ‘I myself have often thought of killing myself,’ he continued. ‘If it wasn’t for the farmers’ movement, I think I would.’

Reddy is chair of the Karnataka State Farmers’ Association (KRRS), one of the largest movements in the world. Founded in the early 1980s, and based on principles of self-reliance, it has already brought together millions of peasants within Karnataka. It has also, according to Reddy, dramatically reduced suicide rates. This may be true, and there are good reasons to imagine why it would be. Social movements provide tangible support and help to communities in need. But they also provide hope, and the promise of change. In India, the KRRS has been working with farmers movements elsewhere in India and around the world to meet the challenges facing their members, through protest, self-help, new farming schemes and rural education, including a programme which translated and distributed a draft of the World Trade Organization’s charter document to the fields. The debate and discussion of texts by peasants in Karnatakan fields happened in 1992, seven years before the WTO’s 1999 Seattle meeting, which is when most of the rest of the world caught on to the WTO’s dangers.

Membership of a movement does not, however, confer immunity from despair. One of the most important descriptions of farmer suicide has come from a South Korean farmer, a former leader of a Korean producer’s movement, who killed himself in 2003. These are his words, from a pamphlet he distributed on the day he died.40

Once I ran to a house where a farmer with uncontrollable debts had abandoned his life by drinking a toxic chemical. Again, I could do nothing except listen to the wailing of his wife. If you were me, how would you feel? … Wide and well-paved roads, and big apartment blocks and factories, cover the paddy fields that were built by generations over thousands of years. These paddies provided all the daily necessities – both food and materials – in the past. This is happening even though the ecological and hydrological functions of the paddies are even more crucial today than they were before. In this situation, who will take care of our rural vitality, community traditions, amenities and environment?

On 10 September 2003 at the World Trade Organization Ministerial meeting in Cancún, Lee Kyung Hae, a Korean farmer and peasant organizer, climbed a fence near the barricades behind which the trade meetings where happening. He flipped open his red penknife, shouted ‘the WTO kills farmers’41 and stabbed himself high in his chest. He died within hours. Within days, from Bangladesh, to Chile, to South Africa, to Mexico, tens of thousands of peasants mourned42 and marched in solidarity, peppering their own calls for national support for agriculture with the chant: ‘Todos Somos Lee’ (‘We Are Lee’).

Lee’s was an activist life. In 1987, he was a leader in the founding of the Korean Advanced Agriculture association. His Seoul Farm, in Jangsu, South Korea was built on unforgiving country, not the sort of land on which Lee’s neighbours thought he’d be able to realize his modest cattle-farming ambitions. Lee went to agricultural college, where he met his wife, and then returned to start farming. He installed a mini cable-car to pull hay up the hill in winter. He started a trend in electric fencing. He poured himself into the land, and into farming. Seoul Farm became a training college, and, in 1988, the United Nations recognized him with an award for rural leadership. It might have ended happily ever after. Except that the Korean government decided to lift restrictions on the import of Australian beef. The Australian government has been a strong supporter of the cattle export industry – Australia is the largest beef exporter in the world – and the concession to increase sales to Korea was a victory not only for Australian corporations like Stanbroke and AustAg, but for the large distribution companies like Cargill Australia and Nippon Meat Packers, owned by US and Japanese interests respectively.

The Korean government knew that the price for cattle would fall with the entry of the cheap Australian beef and so encouraged Korean farmers to make ends meet by upping the size of their herds, the extra cattle being paid for with loans. Following government advice, this is what the Lees did. But the price of beef stayed low and flat, and in order to pay off the interest on the loans, they had to sell cattle. Even shrinking their herd by a few head per month, using the cash to pay the loans, the Lees were unable to keep their land. In the end, Lee Kyung Hae lost his farm. It was the first time that anyone had seen him cry. His family found him in a cinema, in tears, ashamed to be seen in his grief.43

I went to Korea to find out more about why Lee died. At the time of his death, Lee Ji Hye, one of his three daughters, said, ‘He didn’t die to be a hero or to draw attention to himself. He died to show the plight of Korean farmers – something he knew from personal experience.’44 She was halfway around the world when she heard of her father’s death. Kang Ki Kap was there at the time. Also a farmer, he is now a member of South Korea’s National Legislature. Kang used to be a footsoldier with the Korean Peasants Association – he has his finger on the pulse of farmer politics and is a smallholding rice farmer. He, like Lee, knows the plight of Korean farmers first hand. And he sets it into context with the patience of a poet:

The most essential things for human beings are the elements – sun, air, water and food. These are the essential resources for people’s lives. God decided that these things would be the enjoyment of all, so that all might live. He does not intend that we monopolize the elements – yet because they’re so abundant, people treat them as trivial, they do not take them seriously. The trend, the wind behind the WTO, is the globalization of the capitalist system. The fundamental contradiction is the polarization of the rich and poor, with the poor getting poorer and the rich getting richer. Some might say that this is the natural logic of competition. But if you’re a human being with reason and conscience, then the WTO should be eliminated. Especially the agricultural sector and market pressures. Agricultural products should be saved as a human right. To live, people need to eat. You cannot commercialize this. It’s such an anti-human behaviour, not just anti-social, but anti-people.

And what has this to do with Lee Kung Hae’s suicide at the WTO?

The reason I’ve told you all this is because I wanted you to understand the impact that the trade system has had on Korean farmers. The WTO policy is like a bomb to peasants. They can’t even live with agricultural products. Before, a year’s salary was the equivalent of eleven bags of rice. Now eleven bags is US$700, which is one month’s salary. In most of the farming towns, 60–70 per cent of people are seventy years old. Since it’s not so profitable, they’re all in debt. They cannot pay back.

Among the local conditions into which the WTO plays, debt is foremost. The problem of farmer debt is global, and I heard tell of its contours from farmers around the world. The first loan isn’t the problem – it is, indeed, the promise, the hope of a better life. The dream begins to crack when it can’t be repaid. In South Korea, since 1996 a member of the rich country club, the OECD, entire villages have collapsed under debt. With the constant need to find new sources of income, farmers have invented borrowing clubs, guaranteeing loans for one another. They’ve remortgaged their land so often that nobody else will lend to them except each other. So they’ve drawn on Korean tradition, and made use of a socialized pyramid banking scheme. The system involves loans, remortgaging and refinancing to continue to bankroll the loss-making farm operations for as long as they can. It’s as ingenious as it is desperate. It postpones the repossession of land. But it’s utterly precarious. When a single farmer defaults on payment, an entire group is affected. When one goes under, another can’t repay in time, and therefore yet another goes into receivership, triggering an avalanche of bankruptcy.

It’s a reality that farmers in the US also face. George Naylor, a farmer and leader of the National Family Farm Coalition in the United States,45 puts it this way: ‘The truth is obvious to most farmers that commodity prices lower than the early 1970 prices together with prices for things a consumer buys to farm and support a family at year 2000 levels means that it is almost impossible to earn a living on the farm.’46

In any other business, perhaps the owner would have walked away, given up, tried something else. But the land that farmers work is often the land that was given them by their fathers and has been in the family for as far back as anyone can remember. To be the generation responsible for ending that legacy is too much to bear. This was certainly the story with the wave of farmer bankruptcies in the US in the 1980s. And it’s not as if the trends hadn’t been in place for a while. There had been a lengthy process of expulsion from the land beginning in the Dust Bowl years.

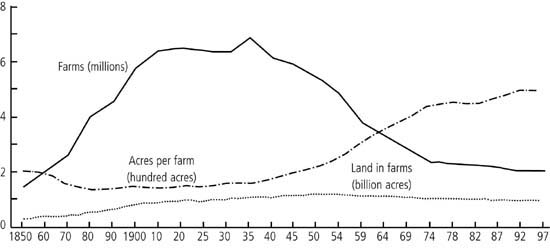

The number of US farms had been falling for decades, while the size of farms had been increasing. Debt had been the singular motor both of the increase in farm sizes and for the destruction of farming families. In a bid to make the farms more profitable, and then in a bid to repay the original loans when the economy turned sour, farmers borrowed heavily, mortgaging the soil on which they worked. When the banks came to repossess the land, some chose death over the dishonour of losing land that had been in the family for generations. The men who died in the US, as would those who would die in India two decades later, fit a strikingly similar profile: middle-aged, devout, well liked, a little introverted and dedicated to their families.47

So why can’t farmers pay their debt? Part of the reason, clearly, is that the prices of most agricultural goods have been falling. Yet low prices aren’t the end of the world, at least in the short term. There are ways around low prices. If you know that you’re going to get low prices, you can plan – you can switch to grow something else, for example. Yet one of the greatest ironies in the shift towards markets in food is that by joining the world market, farmers have lost the very thing that justifies faith in the market’s efficiency – price signals.

Suppose you’re a farmer recently cast into the pool of the free market in, say, South Africa. You look for the return on a crop that will cover your expenses. Maybe you decide to stop growing food crops, and devote your entire land to cotton – between 1993 and 1996, prices for cotton were high. But for six years after that, the prices fell, as the former Soviet Union’s textile industry, one of the world’s largest, imploded. With food crops for consumption in a local market, you know that if there’s a generally good harvest, then your prices will be low, but because you’ve produced enough, you’ll do okay. If everyone produces little, prices go up, and you’ll be okay. But if you’re growing cotton for the international market, you’re hostage to a number of forces far beyond your control or ken. Is the US subsidizing its cotton farmers to produce at lower rates than you could ever produce? Is the slump in the former Soviet Union going to be offset by increasing Chinese demand? And even if the cotton market picks up, is the exchange rate going to be low enough for you to be able to export? Without an effective minimum price system in place, you’ve absolutely no guarantees at all. In other words, globalizing the market has effectively transferred control of farming away from the farmer, and into the hands of those who can shape that market.

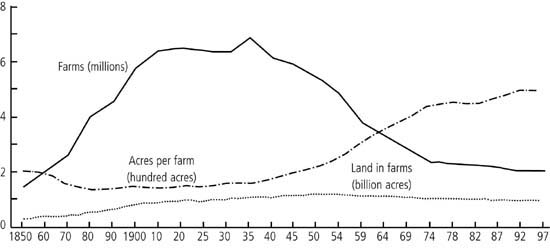

Figure 2.1: Farm size and concentration in the United States 1850–2000 (source: Hoppe and Wiebe 2003).

The market isn’t always shaped through market forces. Or, better, market forces aren’t just supply and demand. ‘The hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist … McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas,’ observes New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman48. What Friedman forgets is that the guns are invariably pointed not at terrorists (or people who look like them). The guns are trained on civilian populations most of all. Particularly in the Global South, poor people are under threat of direct physical harm, never more so than when they try to exercise their rights. In taking a stand against the illegal appropriation of their land, or even in merely raising their voices against the injustices they face, peasant groups across the world are targeted, often with impunity, by local and national forces, both public and private.

The catalogue of violations bruises the imagination.

In South Korea, farmers took to the streets on 15 November 2005 to protest the liberalization of rice imports. Kang Ki Kap had gone on hunger strike for twenty-eight days to try to prevent it, but in the end, the liberalization bill passed by 139 to 66. The Seoul Metropolitan Police, notorious for their liberal use of violence, clashed with the farmers. Many were injured, including Jeon Yong-Cheol, a 43-year-old farmer, whom the police beat over the head. When he returned home that evening, he collapsed. Nine days later, he died of cerebral haemorrhaging.

In Brazil, the targeting of peasant leaders has been an ongoing government and private-sector project. Over the past two decades, and according only to official sources, at least 1,425 rural workers, leaders and activists have been assassinated there. And yet only 79 cases have ever been brought to trial. In 2005 alone, there were 1,881 recorded conflicts in the countryside, with over 160,000 families experiencing some sort of disruption to their security. Further, three workers were worked to death on plantations, and over 7,000 were effectively enslaved.49

Similar stories of oppression can be told about many other countries, from the Philippines to Honduras, from Colombia to Haiti, from South Africa to Guatemala.50 In all these countries, when farming groups and workers try to assert their rights collectively, they face the wrath of local police, hired guns and, at best, judicial apathy.51 For some, joining a movement can be a death sentence. Yet despite the repression, farmers’ movements are expanding.

Collectively farmers have been fighting back. From the US farmer and writer Wendell Berry, to ‘Prof’ Nanjundaswamy, founder of the KRRS farmers movement in Karnataka, India, there are dissenting voices and visions. Chukki Nanjundaswamy, daughter of the late leader, and now an international emissary in her own right, explains her father’s vision: ‘All we want is a fair price. We’re not asking for anything more. My father called it a “scientific” price – a price that includes the cost of growing, the cost of labour, the cost of land. Nothing more.’

One of the other KRRS farmers, Versatanarayanam, says, ‘Our message is this to the world: we the farmers need to stand on our own two legs. We don’t want financial assistance, we know how to do this with our own resources. We don’t want to be dependent on the WTO, the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank,’ he says, naming the other international organizations that have shaped a great deal of economic reform in India (and that are discussed more in chapter 4). ‘What they give, they give to spoil us. We’re not beggars, we’re creators. We have self-respect and we can be self-reliant. We can control our own resources.’ For that to happen, though, the forces that currently control the resources will need to be confronted and dismantled.

‘It’s not me. There’s nothing I can do. I’ll lose my job if I don’t do it. And look – suppose you kill me? They’ll just hang you, but long before you’re hung there’ll be another guy on the tractor, and he’ll bump the house down. You’re not killing the right guy.’

‘That’s so,’ the tenant said. ‘Who gave you orders? I’ll go after him. He’s the one to kill.’

‘You’re wrong. He got his orders from the bank. The bank told him, “Clear those people out or it’s your job.” ’

‘Well, there’s a president of the bank. There’s a board of directors. I’ll fill up the magazine of the rifle and go into the bank.’

The driver said, ‘Fellow was telling me the bank gets orders from the East. The orders were, “Make the land show profit or we’ll close you up.” ’

‘But where does it stop? Who can we shoot? I don’t aim to starve to death before I kill the man that’s starving me.’

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath52

Like millions of farmers at the top of the food system hourglass, Lee Kyung Hae was subject to the choices of others. The price he received for his cattle was beyond his control. The forces that shaped the market staked him at their mercy. He and his farming movement were brushed aside by their elected representatives. He chose to end his life. Even then, the venue was chosen for him. At the invitation of the Mexican government, the World Trade Organization had chosen to hold its 2003 Ministerial Meeting in Cancún. But Lee could pick the time. On Chuksok, the day of the Korean harvest festival and ancestral remembrance, Lee stabbed himself in his chest with his knife.

But what killed Lee Kyung Hae? Lee had used his body as a canvas of pain before – slashing himself across the stomach outside the building of the WTO’s predecessor, in protest at its impending demands on farmers. He had regretted it afterwards, calling it an ‘impulsive and uncontrolled action’. We might simply want to ascribe his suicide to an unstable personality. And yet. Although Lee flipped open the blade, we’re not above asking for reasons that exist outside him. The question is how far we’re prepared to look. The young man who started the Korean labour movement, Chun Tae Il, died by his own hand in 1970. After his death, it was said that ‘his mother killed him’.53 Yet today, we can read his decision to die for the movement as a mixture of romanticism and an assertion of his self in the face of circumstances designed to crush it. The same might be said of Lee Kyung Hae. The words of his last pamphlet weren’t a conventional economic analysis, though they certainly called on economic fact. His analysis was a humanizing paean – one that put a face on globalization by counting the human costs. His statement wasn’t of the ‘goodbye, cruel world’ variety, but a serious and honed critique of the forces that have long been at work on him, and other farmers. If one looks at Lee’s words, engages with them, criticizes them,54 it’s possible to understand his actions as a way of his reclaiming control of his body in defiance of a system that wouldn’t let him. And it’s a system that stretches far beyond the WTO.

Although India served as our point of departure, I’ve argued here that there’s a global crisis facing small farmers, one that’s harder still for the landless and, above all, for poor women. As we’ll see in the next chapter, although the WTO might get the blame for trade liberalization, it isn’t the only, nor the most significant, fund of trouble for farmers. The food system has a web of different treaties and organizations that help to shape it. In Mexico, NAFTA, a prototype for the WTO, was extended to cover agriculture by the Mexican government, against the advice of the US government. In India, the decision to liberalize agriculture was a cocktail of local and imported ideology. Certainly, the WTO gets blamed by national governments, who sigh and explain that they would very much like to support farmers, but are prevented by the WTO from doing so. These governments neglect to mention that they have chosen to tie their own hands, chosen not to be able to help. Why governments would choose to do this, and how trade fits into a broader vision of national development, is the subject of the next chapter.