I believe a lot in focusing on just a few things,” Kazu Kibuishi told an interviewer in 2013, soon after he had been chosen to design new cover art for the hugely popular Harry Potter series. Kibuishi told reporters at the time that he had accepted the plum assignment after a brief bout of uncertainty: up until then, after all, he had concentrated almost all his creative energies on just two related passions: comics and animation.

Kibuishi was still a child when he and his mother and brother moved to the United States from Japan. He arrived in California filled with vivid images of Japanese TV robot action heroes like Ultraman. In college he majored in animation and drew a comic strip called Clive and Cabbage for the student newspaper. Then, after working for a time in an animation studio on commercials and games, he opted for the greater freedom — and risk — of going it alone as a freelance artist.

Kibuishi proved to be highly adept at marketing his work. He launched his adventure strip Copper in 2002 by posting installments on the Web, and in 2004 created Flight, a comics annual, as a showcase for himself and his friends. In 2012 he added the Explorer series, to the delight of his growing fan base.

Kibuishi’s most ambitious project to date has been the long-running Amulet series of graphic novels, which take place within a mythic realm that he continues to elaborate on and explore. “Every time I do a new book,” he reports, “I feel like I’m on a new adventure. . . . I just fall into the story. I let the characters take me somewhere.”

Amulet stories are inventive, fast paced, and as easy to follow as the stories Kibuishi always favored as a child “I like to tell parents and teachers,” he once said, “that classic literature is simply popular entertainment that was popular a long time ago. And kids who are reluctant readers are simply readers who haven’t found a story that engages them.” Kibuishi’s storytelling may flow effortlessly, but his luminous artwork is so painstakingly drawn that fellow comics artist and theorist Scott McCloud once remarked in admiration, “It hurts my hands when I look at it.” Kibuishi now has a studio of his own — Bolt City Productions — where on any given day an app or other media project is as likely to be in the works as a book. As Kibuishi told an interviewer, “I actually have people” — a staff of artists — creating some of the illustrations for his books. “Can you make those backgrounds look better?” He seems rather amazed to have arrived at this point. “I’m the guy,” he says, “who draws less and less.” We spoke by phone on February 25, 2014.

Leonard S. Marcus: What were you like as a child?

Kazu Kibuishi: A friendly guy. I wasn’t a social butterfly, but I didn’t shy away from hanging out with other people. I was a good student when I wanted to be. I was one of the best students in the second half of high school, though not in the first. I got my grades up as soon as I realized I would have to if I wanted to get into a good film school.

I was always into sports. For a long time as a kid, I thought about playing professional baseball. Of course, I don’t know if I actually would have cut it. I played shortstop because that is the position from which you command the field. I liked being in the right place to tell everybody what might be coming next. I would play out every scenario in my mind in advance, so that the minute the ball came off the bat, I knew what was supposed to happen.

It’s exactly the same way for me with my work with comics. With Amulet, people are shocked to see that I do most of the drawing for a book in the last couple of months. I spend most of the time going over all the possible scenarios in my mind beforehand — before I ever put a word or line on paper. Eventually I decide, “This path is probably the smartest one. This will most likely yield the best result.” Once I make that basic decision, I draw the book incredibly fast.

Q: What comics did you love growing up?

A: As a child, Garfield was the comic I always looked to. I wanted to be Jim Davis when I was five or six. I read Calvin and Hobbes in high school. Also, Mad magazine. Mad’s Mort Drucker was another one of my heroes.

Q: Did you grow up bilingual?

A: I came to the U.S. when I was three. I still understand Japanese and can speak Japanese without an accent. But my vocabulary is that of a three-year-old!

Q: Do you feel a kinship with the Japanese comics tradition?

A: Not really. I didn’t grow up on Japanese comics outside of the manga that my grandmother kept on the shelves of her Japanese restaurant in California for the businessmen who would come and have lunch. They weren’t made for kids, but I would look at them now and then, although I couldn’t read them.

Q: What about Erik Larsen?

A: I was a fan of Savage Dragon and of all his Spider-Man issues. He was a childhood hero of mine, too. So it was a thrill when I later met him at the Alternative Press Expo in California, where he unexpectedly came up to the exhibit table of my friends and me and said, “I want to publish Flight” — the first comics collection I edited, with original stories that my friends and I had done.

Q: When did you first see yourself as an artist and a writer?

A: It started with an interest in drawing for Marvel or DC. A high school friend and I would spend our after-school hours drawing late into the night, pretty much every day, and all through the summer. We had this notion to become professional comics artists. Then one day I visited one of the studios where these comics were being published, and I realized I didn’t like the stories they were producing, and that I wouldn’t want to draw them. I saw myself as very much a writer at the time and was writing poems and short stories for my friends as well as for the high school literary journal. So I decided this wouldn’t be a career for me. I thought, “All right, then I’ll be a screenwriter,” and so I enrolled in the film studies program at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

My mom had drilled it into my head as a child that I was going to be a doctor, and I had pretty much resigned myself to the idea early on. My vision of my future was that I might draw caricatures of my patients and hang them on my waiting room wall. I thought how horrible that would be. It was like a fever-dream nightmare! I started to draw more and more, out of fear that it was my last chance. By the time I was a teenager, I thought, “I better get it all out now because I am not going to be able to do this later.” In a strange way, that fear is what eventually drove me into drawing for a living: the fear that I would otherwise have to do something else for the rest of my life.

At the same time, I kept looking for a path that would allow me to continue drawing. After deciding that working for Marvel or DC was not the right choice for me, I began to believe that filmmaking might be a serious vocation, work that would allow me to put my skills to good use.

Q: What led you back to comics?

A: While I was in college, I drew a daily comic for the school newspaper. The deadlines were really tight, and I learned to work like a professional. And I ended up producing a tremendous amount of content that I was able to carry away with me after school. I wasn’t sure what my film degree qualified me for, but my comic strip helped me get jobs as a graphic designer and as an illustrator for magazines.

Q: It sounds like you were open to trying lots of different things.

A: For a time I worked as a graphic designer at an architectural firm. It was the wrong job for me in every possible way. I completely shut down and actually ended up having a nervous breakdown. After that, while I was living at home with my parents for a while, I started my comic strip Copper, which is about an adventurous boy and his fearful dog. I was able to explore some philosophical ideas that interested me, and it was a good chance for me to work some stuff out. Initially, I drew Copper for a magazine that no longer exists called Yoke, and it was unpaid work. I later serialized it myself on my website, and that is when it took on a life of its own. Scott McCloud and Jeff Smith — two of my heroes — found it there and reached out to me. They told me my work was great and that I should continue doing it. I was working at an animation studio and drawing Copper in my free time. Eventually I was able to spend all my time doing comics.

Q: How did you get involved with web comics?

A: When I was starting, Scott McCloud had a group of web comics artist disciples. I thought that one of them, Derek Kirk Kim, was drawing the best comics anywhere. At the time people thought that web comics were amateurish — that a comic had to be published in order for it to be a serious piece of work. It was really just a snobbish thing, in the same way that for a long time people thought that film was automatically better than television. But seeing Derek’s work on the Web changed all that for me, and he inspired me to create my own website and to post Copper there.

After college the Web gave me the ability to create my own newspaper. I designed my site to look like a newspaper. At that point I was almost addicted to drawing comics. I needed to do it, and it didn’t matter if I was being paid to do it or not.

Q: How do you see film in relation to comics?

A: I worked in film animation for a time and enjoyed it. But I came to feel that there was a glut of talent in the film industry. It seemed that a lot of very talented film people were just waiting in line, and that many of them would probably never have the opportunity to show off their stuff. I felt, “I’m really not needed here” — and it started to dawn on me that it was a better idea for me to go someplace that needed me a little bit more. When I looked at the comics world, it was kind of a sad story. I thought, “I used to love this place, and look at it now.” There wasn’t much out there besides Jeff Smith. I followed Jeff in on the same path. I wanted to be part of what I thought of as a rebuilding process for comics.

One of my goals has been to introduce comics to young readers and create a love for comics at an early age. That’s one of the big reasons I got into doing comics for kids, even though some of my friends thought that kids’ comics were not “serious” work. They can be serious, of course! And that is what led me to start Amulet. I was twenty-four or twenty-five at the time and didn’t have any kids yet. So it was really difficult for me at first to get into the right mind-set.

Q: Would you want the Amulet series to become a film?

A: Most definitely! It was always meant to become a movie or series of films. My hope is that the movies and the books will coexist well, in much the way that that is true for Harry Potter. I think everyone involved with Harry Potter took good care of the mythology. I would not want the movies to stamp out the books.

With the big Hollywood superhero movies, most people don’t even realize that the stories started out on the printed page. The comic book artists and writers who created them are almost never mentioned. On a recent trip to Cleveland, I decided to visit the various local sites of historical importance to comics. I drove to the house where Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster wrote the first Superman comics, for instance. It’s just a guy’s house, with a plaque outside. But the owner invited me in and showed me his collection of Superman bobbleheads. He showed me his Superman Room!

Q: How do you feel about turning the “classics” into graphic novel form?

A: I would love to do a graphic novel of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine. Ironically, with all the work it takes to keep the Amulet series going, I don’t know when I’ll have the time to do it. A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin is another classic I would love to do. One reason for my interest in doing so is that A Wizard of Earthsea is a hard book to read, and I think that a graphic novelization of it might help the audience it was intended for.

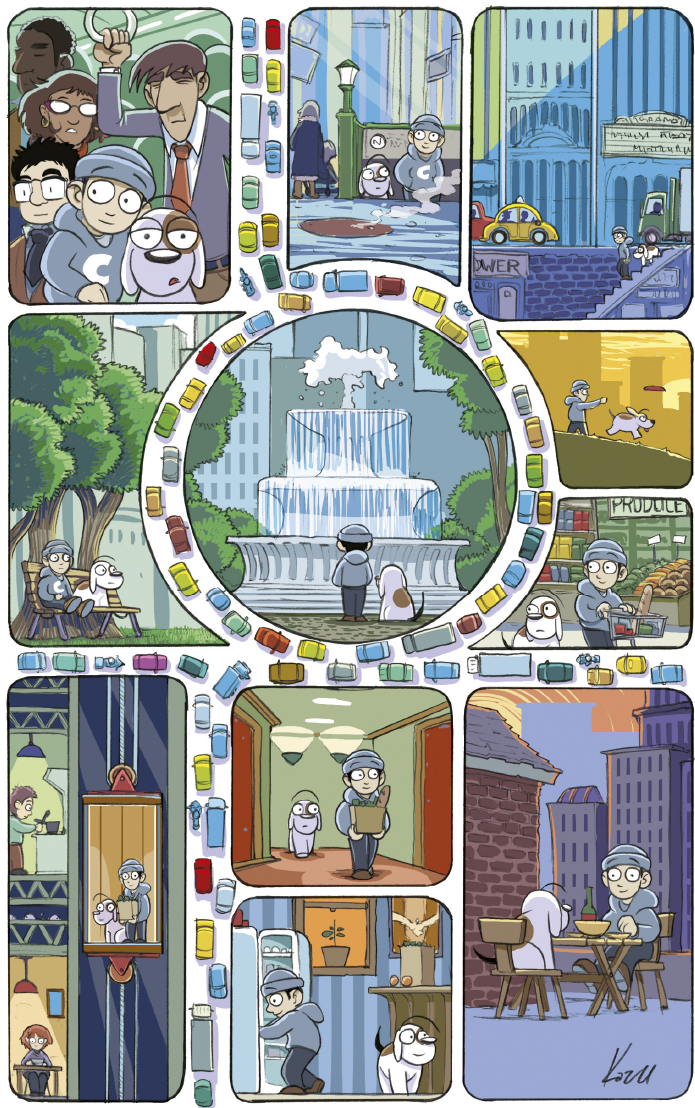

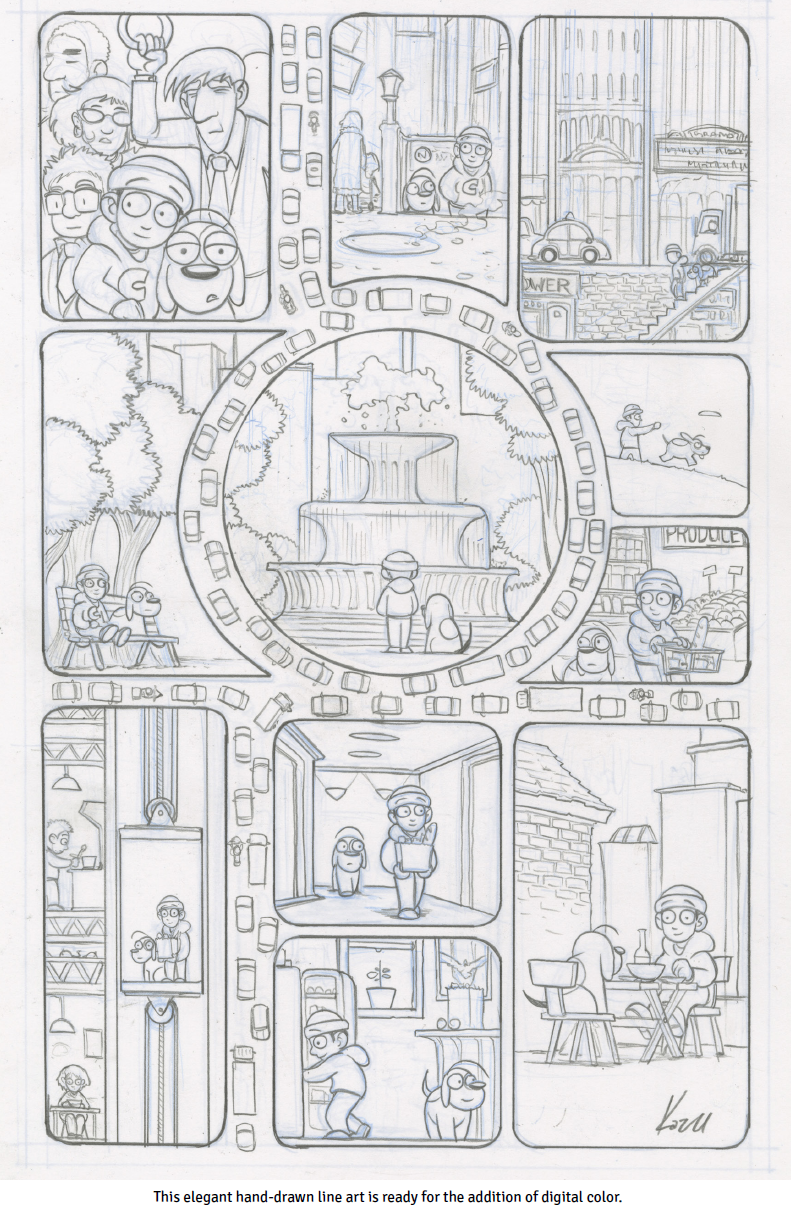

Q: Tell me about the comic you created for this book, “Copper.” It looks back, in a way, to your beginnings in comics.

A: When I hear the word “city,” I immediately think of New York City first, so I chose to depict life in New York in this comic. I was born in Tokyo, grew up in Los Angeles, and have traveled all over the world. So I’ve always been familiar with big cities, but nothing really compares with New York. The comic is a little tribute to my friends in the publishing industry, most of whom live in or near Manhattan, and I loved getting another chance to draw my characters Copper and Fred. My focus has been on Amulet for several years now, and I’ve rarely had the opportunity to draw these guys, so this was a great chance for me to spend a little time with some imaginary friends as a tribute to my friends in real life.

Q: Do you find some things hard to draw?

A: As long as I know what a thing looks like, it’s not hard for me to draw it. I have a bunch of shorthand techniques that allow me to mold things I’m very comfortable drawing to look like things I’ve never drawn before, based on their shape and volume and form and viscosity. I guess I think like a 3-D animator. I build a drawing like someone building with LEGOs. I carry a sketchbook everywhere I go and draw so much that it’s really not hard anymore. It’s like shooting free throws for a basketball player.

Q: Why do comics artists so often band together as friends?

A: Because making comics is still an outsider’s profession. Often the artist’s family is disapproving. They’ll say, “This person is not going to do well in life!” So you’re bonded by the idea that you’re bound to be a failure before you start. This has changed quite a bit for the better in the last few years. Still, the superstars who make a tremendous living as comics artists only come along once or twice in a generation.

Q: Do you hear from your readers?

A: I was just in San Antonio with thousands of kids who are big fans of Amulet. Events like that one get bigger and bigger each year. When I first started, maybe one person would show up! I feel a great responsibility to them. My job is to give them the best book possible. There’s Amulet fan fiction now. Some kids are starting to put my characters in relationships I never intended.

Q: What is the most satisfying thing about doing your books?

A: I don’t know if I can point to just one thing. Every time I make an Amulet book, it’s as though I am getting to direct a big-budget movie, but without having to spend all that money to do it. It all just comes from my brain, I get it down on paper, and then a ten-year-old can see pretty clearly what I am trying to do. That’s an amazing experience. Being able to share a vision with somebody is very exciting in any field.

Then there is the interactivity I have with all the teachers, librarians, and students. I think of myself as a worldwide teacher’s aide. By creating books that kids like to read and by visiting with schoolchildren, I am in a sense making it easier for teachers to do their jobs. And I love knowing other comic book artists, who are some of the best people I’ve ever met. Being part of that community is fantastic.

One more good thing about what I do is that because I work at home, I am able to be with my family all the time and to watch my kids grow up every day. I don’t know too many people who get to see their kids so much of the time. That’s a huge, huge thing — for me anyway.