MY INTRODUCTION TO Blair Road was rather different from what I had imagined, although I remain even today incapable of saying precisely what I had expected. Perhaps a more enthusiastic reception from my father, some clear welcome of me as his progeny? Or possibly a restoration of that old snug and protective sense of security I had felt previously with Ah Mah, instead of a grey stretch of vague hopes and unspecified fears.

During the voyage across the South China Sea, Ah Mah had provided a measure of warmth and attention. Once back on dry land, however, I quickly detected a difference.

The clues came from the perfunctory way she had presented me to my father and, later, to Anna. She did not even put in a good word on my behalf with either. She behaved as if she herself had come back under a cloud, like a plenipotentiary returning from a mission with less than what had been expected. It seemed the entire household had an intimation of a plan gone awry.

I tried to get to the bottom of my grandmother’s diminished concern for me. It was patent the clock could not be turned back. I had been an infant three years ago and now I was a boy far too big for a woman on the wrong side of 60 to pick up and cuddle. It would probably make both our skins crawl with embarrassment if she were to attempt to snuggle her face against my belly as before or on another ticklish part of my body.

Demands upon her time had also multiplied. She now had two more grandchildren by Anna to fuss over and three aunts to assign duties to, including selecting one of them each day to help comb and braid her hair into a chignon.

Then there would be the daily instructions to Ah Sei about what to purchase for meals and soups, particularly for soups intended for my father. The requirements for a slowly-brewed beef broth with medlar seeds would be different from those for a tonic made with cordyceps and dried scallops. Her concern for my father’s nourishment seemed to have grown in importance, although there was not the slightest indication he was suffering from any form of ailment.

I, of course, had no knowledge of other developments affecting the household or any inkling of my grandmother’s personal misgivings or concerns. I was largely ignorant of what was happening at No. 38, until rumours had gained currency of the birth of a boy by another grandmother living there. Even then, no one took me to meet my baby uncle until my grandfather did so about a year after the birth.

Where I myself fitted into the larger family picture I divined only slowly, from overheard remarks made by adults. It appeared that my grandparents, particularly my grandmother, took the view that sons born to my father belonged unquestionably to the Wong family. Hence it was felt my mother, after divorce, should hand Tzi-Choy and myself back to the family. The Canton visit by Ah Mah was to that end. Disappointingly, she ended up only with me.

How my grandmother and my mother had decided my fate remained a mystery for years. Nobody at Blair Road was prepared to enlighten me, perhaps because only Ah Mah knew the full story. I had to wait until I was 18 before I got an account from my mother.

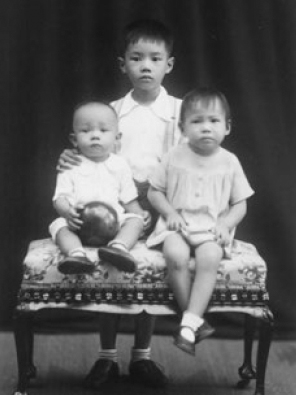

A studio portrait of me standing behind my brother Francis (L) and my sister Helen (R) in 1936.

“Your Ah Mah wanted both of you, as rightful members of the Wong family,” she said, straightforwardly. “But, as a mother, I wanted both of you too. Yet I could see no way of supporting both on my income, let alone providing the kind of education you should have. It was vexing. Your grandmother insisted on at least having you, as the first-born. I had to agree, in order to keep Tzi-Choy. Your brother was much younger than you. He needed more attention. That was how things got decided.”

I am not sure, even today, that my mother had told me the entire truth. Because we had met after a lapse of 13 years, both of us had been too reticent for much straight talking. I suspected she must have found my proneness for demanding reasons and explanations for everything too hard to handle. That could be a reason why I had been allowed to go. It was impossible for me to cross-check my mother’s account because Ah Mah had passed away by then.

I therefore wallowed in ignorance in Singapore, living life in a strange and ill-structured kind of limbo. In order to occupy myself, I tried to familiarise myself with the goings-on and the internal features at No. 10.

Apart from the highly visible collection of books, my first discovery was the existence of a five-inch square panel in the wooden floor on which I was initially asked to sleep. It had been fitted so expertly that a casual observer would hardly notice it, let alone realise it could be lifted up to form a peephole looking down upon the main entrance of the house.

Should a visitor knock at night, after most of the family had retired upstairs, he or she could be discreetly examined from the peephole or to be asked for identification before anyone needed to go downstairs to answer the door. I was to learn before very long that the people who sometimes dropped by during evenings were Christian ladies who lived in the neighbourhood. They came to socialise with my grandmother or to indulge in a low-staked game of mah-jong with her.

I thought the spy hole an ingenious idea and was thrilled that I had uncovered it so quickly.

My second discovery came a day or two after the first. It drove home the lesson that things were seldom what they seemed.

All the windows in the house had sturdy steel bars installed into their frames, each spaced so that even an active child could never squeeze through. Their purpose, no doubt, was to indicate to potential thieves and burglars that the place was securely protected.

But while looking out idly from the centre of one of the three front windows upstairs, I began fingering the bars and found a little give in one of them. Unlike the rest, it had not been firmly fixed into its sockets. The bar could, without much effort, be rotated. Why should that be? Had the builders overlooked the need to fix it properly to keep criminals out?

In order to find out, I took hold of the bar with both hands and shook it with all my might. It remained in place. Further investigation, however, revealed that there was ample space within the top socket for the bar to be pushed upwards, so that the bottom end of the bar could be completely disengaged from its lower socket. I proceeded to do so, not realising that the steel bar was heavier than I had expected. Maintaining a hold over it unbalanced me. I emitted a cry as I struggled under its weight. My cry drew Aunt Kwei from the enclave where she had been changing the sheet on my grandmother’s bed.

“What are you up to now, you nosey boy?” she cried, when she saw me grappling with the metal bar. She dashed forward to relieve me of it and to replace it in its sockets.

“You shouldn’t play with that,” she said. “We mustn’t let outsiders know it can be taken out. It has been left that way to provide an alternative escape route in case of fire.”

“But couldn’t that allow thieves and burglars to come in that way too?” I asked.

“Not unless you keep showing it to the rest of the world.”

My next discovery, however, was of an entirely different nature. It shattered me utterly.

It happened late one morning. I was attracted by funny noises and the sound of laughter coming from my father’s room. My curiosity drove me to investigate. I found the curtain over the doorway drawn to one side. Inside, my father was lying on his back on the fourposter bed, holding baby Francis directly above his reclining form. He was playfully shaking the infant and making gurgling sounds. The baby was responding by giggling and waving his limbs. Even the brass bedstead seemed to glisten with reflected merriment.

Anna and Helen shared the bed. They were sitting on the inner side, next to the window, with their legs folded beneath them. Their lips were parted in expressions of joy.

I stood at the threshold, taking in that happy scene. I anticipated an invitation, from my father at the very least, to share in that merriment. But nobody except Helen paid me the slightest attention. She looked in my direction and our eyes locked; hers conveyed their usual look of bewilderment and hesitancy.

When the two adults continued to act as if there was no one standing at the doorway, it came to me I was unwanted. I retreated from my vantage point, dazed with confusion and disappointment. On reaching the staircase, I sat down on the top step.

The world seemed to be collapsing around me, in a weird, slow motion kind of way. Why had I been brought to this house, to this alien place? What was I supposed to do here? I did not belong. My father had manifested once again his lack of interest in me. He had said hardly two words to me since my arrival. What did he have against me? Did he consider me a blight on his happiness, a reminder of a part of his life he would rather forget? None of it had been my fault. I had not wanted to come, and I had been well behaved since my arrival. I had thrown no tantrum, made no unreasonable demand, picked no fight with anyone. Yet he had already judged me unworthy of his attention.

My priestly maternal grandfather had declared the world filled with sinners. I must be one of them. My father must have seen me as sinful, uninviting as a scarecrow, a child unceremoniously dumped on him!

Everybody needed the grace of God to escape damnation, Kungkung had also said. But where could I find the grace of God?

The prospect of being sent home like a cur, with its tail between its legs, filled me with alarm. Then it dawned on me I no longer had a home. My mother had already cut me loose, keeping only my brother. A deep-reaching sense of being abandoned overwhelmed me. I saw myself condemned, trapped, with no way out.

The echoes of laughter continued to resound from my father’s room even as I tried to grapple with my predicament. At the same time, sounds drifted up from downstairs; the voices of Ah Mah and Ah Sei, talking unhurriedly about dishes for the evening meal. Through the uprights supporting the handrail of the stairs, I could see Ah Yeh lounging on his favourite rattan chair, his upper body hidden behind a spread-out newspaper. They seemed totally unaffected by my misery.

As I floundered helplessly, tasting the bitterness of rejection, Aunt Soo-Leung came briskly out from the front room. In turning abruptly at the head of the stairs to go downstairs, she almost crashed over me.

“Oh, my goodness!” she exclaimed, as she righted herself by splaying a hand against the wall. “What in heaven’s name are you doing here, sitting by yourself in the gloom?”

“Thinking,” I replied, giving her a doleful look.

“Thinking? At your age? What about?”

I shrugged. I could not bring myself to tell her of my distress.

“You’re queer, all right,” she said, weighing my silence. Then she chuckled. “I see your father hasn’t misnamed you after all. Come on downstairs; I’ll give you a sweet.”

I duly followed her.

That night, sleep was erratic. An oppression without a name played havoc with me. I noticed moonlight streaming in through the barred windows, casting a bright glow upon the polished floor I was on. The moonlight did indeed resemble ground frost.

Li Po’s poem, taught by Miss Nice, came back to me. As I recalled the lines, an inexpressible longing for some place I could call home washed over me. But where was my home? I tried to touch the moonlight, believing for a moment it might be something solid and real, until it slipped between my fingers like an ungraspable dream.

In the days that followed, I moped around. I felt dissociated from the household and the people in it. All around me activities continued in their accustomed manner. My grandfather went about smoking one of his pipes, reading his newspaper and feeding his canary; my grandmother talked to Ah Sei or waited for her hair to be done; my father flitted in and out, with barely a glance in my direction; my aunts busy with their daily routines; Ah Sei chopped vegetables or scrubbed clothes on a wooden washboard.

Connecting with Anna and her children was even more out of the question. For much of the time, my siblings had their own little world with their mother, inside my father’s bedroom, a place where I was not welcome.

Did I really belong to the Wong family? I kept asking myself that question. Though blood was said to be thicker than water, ties of blood seemed to provide only the frailest of bonds. Neither did being the first-born command much standing or respect. Was life supposed to be like that? I wished somebody would explain things to me. Nobody did.

I would have to find out on my own, I concluded. But how? I could not read. Nonetheless, I had found illustrations in some of the books in the glass-fronted cupboard. If I could find more books with pictures, they might throw light on some of my quandaries. I began riffling through them.

The ones in Chinese, printed on flimsy rice paper, proved a dead loss. They contained no pictures. I concentrated on English ones and became so engrossed that the adults began regarding my activity as peculiar for a child unable to read. They assumed I was living up to my name. Once adults had assured themselves I was treating the volumes with care, however, they left me to my strange pastime.

Searching for pictures represented one of my earliest steps onto that long and shaky ladder of knowledge. I had no notion then how much effort was required to refine knowledge into understanding and then perhaps into wisdom. Nor did I have any inkling then how some kinds of knowledge could mess up a person in unpredictable ways.

It was Ah Yeh who first showed me aspects of Singapore beyond the precincts of Blair Road. Perhaps he had some kind of plan all along or perhaps he just wanted to divert me from rummaging through his medical tomes. I had no way of knowing. All I can remember is that one day, out of the blue, he picked up his khaki-coloured topee and said: “Put on your shoes. I’m taking you out.”

I was so unprepared for that command that all I could do was to obey. Thus began a series of visits to members of my extended family, to relatives I scarcely knew I had.

The first visit was to the oldest of his adopted daughters. She was older than my father. I therefore had to address her as Eldest Paternal Aunt, an honorific different from the ones I used for the other aunts living at No. 10. She was married to a man named Kan Cheung-Wan who worked in a goldsmith’s shop. They lived in an apartment on the first floor of a building in Upper Cross Street. They had several children, most of whom were older than myself.

Subsequent visits took me to the homes of two other aunts, one of whom I was told to address as Second Paternal Aunt and the other as Aunt Tim. The former was named Wong Kum-Yin and she was married to a bank worker by the name of Chan Po-Ying. Aunt Tim was married to an office worker surnamed Yeung.

But Aunt Tim was a fair bit older than Second Paternal Aunt, so I could not work out how they and the aunt at Upper Cross Street fitted together. Moreover, I had already met in Canton another paternal aunt older than my father. It was all very confusing. But as with most things in my family, the precise hierarchy and inter-relationships of all those paternal aunts were left fuzzy and unexplained.

All the three aunts I met during those sojourns were warm and chatty. They were typical of Chinese lower middle class housewives living in the Straits Settlements of that era. Their wants were simple and so were their ambitions. They did not stand on ceremony or go in for social one-upmanship. They desired little more than a roof over their heads, food on their tables and a sound education for their children.

Each of them welcomed me in a manner appropriate to a junior member of the family. Each plied me with lavish treats and subtle questions. The latter centred on the activities of my mother, my brother and other family members in China and Hong Kong. They knew more about my circumstances than I did. I happily scoffed their treats and fudged the answers to their questions. In reality, some of the questions they asked were ones I had been asking myself.

I noticed after a while that neither Ah Mah nor my father ever joined us on those visits, though Aunt Soo-Leung regularly did. I did not know why. I did not enquire for fear of getting another of those non-answers adults were prone to give, which would only baffle me more. So I merely kept my eyes and ears open. I soon noted that the welfare of my outside aunts and their families seldom came up in conversations within No. 10. The aunts themselves also rarely visited Blair Road.

Those trips with Ah Yeh petered out soon after I started my formal English education. My school and homework regimes proved too demanding for me to afford the time. My grandfather continued making them, however, either on his own or with Helen and Aunt Soo-Leung.

Nonetheless, those visits enabled me to establish a few quite decent friendships with my different broods of cousins.

Meanwhile, not long after my first excursions with Ah Yeh, Ah Mah started taking me out of the house as well, albeit only for short distances, to the shops along Kampong Bahru Road, just around the corner from Blair Road.

One of those early outings was to a grocery store run by a fat, jolly Chinese proprietor. My grandmother must have been a regular customer because she and the proprietor fell easily into conversation.

“How are you, Madam Wong? And how is the venerable doctor?” the proprietor lilted in welcome. He had thick, fleshy lips and a nondescript nose. He was casually under-dressed, clothed in only a white singlet and a pair of black trousers.

“Very well. Thank you for asking,” Ah Mah replied.

“Good, good. And this young sir must be one of your grandsons, if I’m not mistaken?”

“Yes, the eldest.”

“Ah, getting quite big now. Started school yet?”

“Not yet, but soon.”

The proprietor turned his gaze to me. “What’s your name, my little friend?” he asked.

My grandmother answered for me. “We call him Little Ki. He’s barely six; but already quite good at reciting poems.”

“Oh, really? How nice! It’s never too early to learn poetry.” Then, returning to me, he added: “How about reciting a poem for me, Little Ki?”

I glanced at Ah Mah.

“Go on,” she encouraged. “Recite something for this uncle.”

I dipped into my limited repertoire and declaimed the first poem that came to mind. It was a Tang one frequently taught to children, about a man who had left his native village when young and returned when old and saddled with thinning sideburns. Though he could still speak the village dialect, the children there gazed upon him without recognition and laughingly asked where the “guest” was from.

“Very good, very good!” the proprietor exclaimed. He bunched the fingers of his right hand, stuck up the thumb and waved the hand in a gesture of approval.

I was taken slightly aback, that a man in his position should have reacted with so much enthusiasm to a few parroted words. I had no appreciation of the wistfulness associated with those lines when I learnt them in Canton. I was simply repeating sounds, without much in the way of imagery.

“That fine performance deserves a treat,” the proprietor continued, with a broad smile. So saying, he reached for one of the jars resting on a shelf near the counter. It contained sour plums. He extracted one and held it out to me.

I looked again to Ah Mah for instruction. When she gave a faint nod, I thanked the proprietor, accepted the sour plum and popped it into my mouth.

As Ah Mah engaged the proprietor in an exchange about the prices and qualities of various products, I took the opportunity to examine the shop and its contents, sucking merrily on the delicious sour plum.

The store was rich with pungencies. It only had a meagre selection of fresh vegetables, like spring onions, string beans and the like, but it had an abundance of less perishable fare. On display in wooden bins, metal containers, gunny sacks and cardboard cartons were dried mushrooms and scallops; edible fungi and dehydrated cole; salted and jellied eggs; polished rice, ginkgo nuts and a variety of beans; and a seemingly endless range of other edibles.

My main focus, however, was on the shelves near the counter. They displayed an array of round glass bottles with metal lids which—apart from the sour plum I was savouring—contained coconut candy, peanut brittle, preserved lemon, liquoriced ginger, hawthorn cakes, almond biscuits and many other mouth-watering delights.

It occurred to me at once that I should miss no opportunity to persuade Ah Mah to take me on future shopping trips. If I could master a few more poems to tickle the fancy of the fat proprietor, I might in time get to sample all the goodies in his shop. But I was left with few opportunities to learn more Chinese poems once I began English school.

My grandmother’s casual remark at the grocery shop about my starting school was soon put into practice. She took me to Chinatown one day and enrolled me in a Chinese primary school for boys. It was a small private establishment, with only between 20 and 30 pupils but with a notorious reputation for being strict on discipline.

Before the first week was out, I found myself in hot water. I cannot now remember what I had done or what rules I had broken. It could not have been anything more serious than what I had done back at kindergarten in Canton. It was entirely possible I had been more fidgety and less attentive than I should have been in that new environment. In any case, I got marked down for punishment.

The school had its own system for dishing it out. Its ethos belonged to that distant era when offenders were still put on display in stockades. Saturday was designated a day for punishments. Accordingly, on that morning, all students were required to be present to witness justice being delivered.

Those selected for punishment had to turn up in the company of a parent or guardian, to whom the reason for the punishment and its severity would be explained.

Punishments were dispensed by way of a rattan cane. Strokes were delivered upon the calves of an offender. The number varied according to the school’s view of the severity of each offence. The headmaster had laid down that he himself would inflict all punishments, to maintain a uniform standard of execution.

In order to prevent anyone from jumping about or hiding behind a parent or guardian while punishment was being meted out, an offender must first mount a small square stool with three legs. It stood about 16 inches tall and was a devilishly cunning device. It ensured that any attempt to dance about or to evade the cane would send the culprit tumbling onto the floor. Experience had also probably determined that its height was the most convenient for delivering strokes on little boys.

Objections by parents or guardians were entertained but only on the basis that the student concerned would then be forthwith and permanently removed from the school.

I had never been caned or beaten by anyone before, so I was not particularly frightened at first. It transpired I was not the only one destined for punishment that morning. There were two others. The one who went before me had been marked down for three strokes.

I watched as he mounted the stool. He let out an almighty yelp when the first stroke struck home. I noticed that he merely jiggled his legs a little and kept both feet planted squarely on the stool. He had evidently been caned before and knew the danger of lifting either leg. He continued to cry out on the subsequent strokes but he managed to endure all three without tears. His mouth merely became distorted, while his nostrils quivered.

Then it was my turn. Having seen punishment inflicted, I was filled with apprehension. I was also due for three strokes. Since my grandmother had not objected to my punishment, I had to mount the stool. My mouth went dry. When I saw the grim faces of my fellow students, I resolved to do better than my predecessor and not cry out.

I scrutinised the face of the headmaster as he approached. He was flexing and swishing the cane menacingly, in preparation for his work. His eyes were as frank as malice itself. It came to me that somewhere inside him, some dark spirit must be lurking, secretly rejoicing in the foreknowledge of pain about to be inflicted. Because he had identified a supposed wickedness in his victims, he was about to beat it out of them.

I steeled myself for the ordeal, reminding myself not to cry out. I succeeded under the sting of the first stroke but could not avoid crying out on the second. By the third, I was releasing a flood of tears. I was trembling so much and wailing so loudly by then that I could not step off the stool. My grandmother had to help me down.

My legs had turned to jelly; I could hardly stand. My eyes were swimming, my mind too dazed to think. Beyond mind and physical pain, I knew that something deep inside me had been violated. And for that violation to be carried out in public and to be accompanied by tears was too much. My cup of humiliation overflowed.

My grandmother half-lugged and half-carried me from the premises. She hailed a rickshaw. After we had boarded it, she placed one arm around my shoulders and used the other to press my head gently against her chest. I sobbed all the way on that slow, jogging journey home.

By the time we reached No. 10, three red swellings had appeared on each of my calves.

Ah Sei was the first one in the house to notice my tear-stained face and the red ridges on my calves. “Aiyeh! Yum kung!” she cried. “Truly yum kung!”

There is no English equivalent for the common Cantonese utterance she had let out. It is usually a cry of sympathy for someone who has suffered some unexpected or unjust misfortune. It suggested more than sympathy, for it also seemed to embrace other human sentiments like commiseration, regret, sadness and reproof against whichever authority, be it man or god, which had been responsible for the suffering.

Ah Sei’s shrill cry drew the attention of my grandfather and a couple of my aunts. My aunts let out another chorus of “yum kung”, accompanied by much shaking of their heads. My Ah Yeh, however, took one look at my swellings and said with wry nonchalance: “I see you’ve been promoted to sergeant.”

I did not catch the meaning of his remark at the time. I just watched dumbfounded as he turned quickly and went upstairs. He returned a few moments later with a jar of ointment.

“Use some of this on him,” he commanded drily, to no one in particular.

Ah Sei duly did the honours. I think the ointment was Vaseline.

I became the centre of attention in the household for the rest of the day. Helen and Francis let out innocent gasps of horror as well. My father, however, remained locked within his silent world. His handsome features betrayed no emotion as he took in the marks on my calves. His eyes might have clouded a little but he said nothing. Was it a display of manly stoicism for my benefit? I could not make out his reaction.

Anna also displayed placidity, without expressing any opinion.

By evening, the weals on my calves had turned bluish-purple. They were tender to the touch but otherwise troubled me with no more than a tight, tingling sensation.

Sleep eluded me that night. As I lay on the floor a short distance from a gently snoring Aunt Kwei, I tried to nut out, in my own immature and untutored way, the meaning of what had happened. Everything seemed baffling and incongruous.

I realised I had little in the way of experience to fall back on. The few fragments of knowledge I possessed seemed to lie unconnected, like meaningless pieces from a huge Lego set. If I could fit them together, I reasoned, they might reveal some kind of design or pattern. For instance, my grandparents must have known the nature of the school they sent me to. My grandfather’s reaction to my cane marks imputed as much. My grandmother’s actions had been even more specific but also more puzzling. She had not objected to my being punished when she had the chance. Yet, afterwards, she behaved as if she were filled with regret. Why?

And what of my father? His very silence also betrayed a lack of surprise. He therefore had to be aware of, if not actually complicit in, the decision to send me to that school. What kind of game were they all playing? And to what end?

My thoughts suddenly switched to my Kung-kung again. I recalled his earnest voice telling me, more than once, that humanity was full of sinners. The crucifixion of Christ was inevitable, in order to save mankind. But what had that to do with me? Jesus was the Son of God. I was just an ordinary boy. Was I being turned into some kind of sacrificial lamb? My mother had surrendered me to keep my brother. My father had displayed what I had taken to be indifference over my beating. My grandparents had vacillated. Was the beating only a prelude to other trials? My mind boggled with uncertainties.

I did arrive at one conclusion, however. I had failed myself. I had resolved not to cry out but could not keep my own promise. An old childhood story came back to me. It was about a hero facing a terrible fate, declaring that a true man would rather shed blood than tears. By that standard, I had a lot to be ashamed of.

Could I do better in the future? That depended on the further trials adults might still put me through. The way their minds ticked over was an annoying unknown. If I could somehow crack their mode of thought, I would not be so much at their mercy.

The need to understand them became so pressing that I was tempted to roll over immediately to where Aunt Kwei was slumbering, to wake her up and to ask for help. She might be an adult but there was an off chance enough of the child was still left in her for her to sympathise with the torment eating into me.

In the end, I decided against it. Even if I only whispered, talking in the dead of night would probably wake up all the other adults in the room. It would not do. I would have to discover the means for handling grown-ups by myself. So I steeled myself for a return to school on Monday. I was determined to learn its rules, obey them and submit to them, until such time as I could discover how to get around them.

On Monday morning, as I was preparing myself for school, Ah Mah surprised me by saying I would not be going to the Chinese school any more.

“Your Ah Yeh is going to find you a new school,” she said.

Thus it came about that I was released from classes for the time being, until a new institution could be found for me the following term.

It was just as well that I was free from school commitments because I was soon visited by another disaster.

One day, sometime after the marks of my caning had faded, Ah Sei was supervising me in taking my shower. As I was ladling cold water from the pot-bellied jar over myself, the old servant came up to me. She suddenly took hold of one of my shoulders and began examining something on my back.

“Any pain on shoulder?” she asked.

“No, why?” I replied.

“Hmmm. Any itching?”

“No! What is it?”

“Only insect bites, I think. On right side.”

Since I could not see my own back, I reached over with my left hand to explore what was there. My hand encountered a small cluster of tiny bumps or blisters, at roughly the same level as my armpit.

“You sure you feel nothing?” Ah Sei persisted.

“Yes, sure,” I cried, annoyed over not knowing why she was making such a fuss over insect bites. There were mosquitoes and bugs aplenty in the tropics. Their bites were a condition of life.

Ah Sei came to me every couple of hours after that, lifted up my shirt and scrutinised my back again. I felt a little put upon because she kept mum over what was causing her concern.

The next day, however, she discovered another cluster of blisters on my back.

“First Born got Flying Serpent!” she cried out to my grandmother. “It’s circling him! If circle completed, he dies!”

My grandmother took a hurried look and quickly called for my grandfather. I still did not know what the excitement was all about, particularly the mysterious reference to possible death. I felt only a minor itching on the blistered spot on my back.

“Shingles,” my grandfather pronounced, after he had examined the eruptions. He dismissed as alarmist the old servant’s talk of flying serpents and death. Just old wives’ tales, he muttered, before going upstairs to fetch some pills. He asked my grandmother to give them to me at regular intervals.

By evening, however, I had developed a temperature. By the following morning, my temperature had risen and I was suffering from a headache as well. After coming downstairs, I just stretched myself out on the ebony settee under the staircase. I seemed robbed of energy even to move further.

Ah Sei was the first person to ask after me and to examine my back.

“Aiyeh!” she cried, before quickly disappearing, only to return shortly with a cold compress and with my grandmother in tow.

“Just look! Just look!” she said, in an undertone, after showing my grandmother my back. Her high-pitched voice was filled with urgency, though calibrated at its lowest volume. “See? Two more! Coil of Flying Serpent circling. Foreign medicine no good. Must have Chinese herbal cure. Or he dies!”

My grandmother, naturally, sought out my grandfather again. He in turn took my temperature and gave instructions I should continue to take his pills. Otherwise, he seemed unperturbed by my ailment.

I did not know what was afflicting me and I did not know whom to believe. Soon, I began to shiver uncontrollably.

That development might have moved my grandmother, for she quickly left the house and returned shortly afterwards with a jar of pinkish-brown paste. She handed the jar to Ah Sei, who swiftly applied the paste to the bunches of blisters on my back.

After two more days of high temperature, my fever broke. The blisters began disappearing from my back, all except the first batch on my right shoulder. Those blisters had flattened noticeably, however, though I could still feel them with my hand.

“That is head of Flying Serpent,” Ah Sei said, after I had more or less recovered. “Still alive. Must kill with hot iron, burn to death for good. Otherwise can flare up again.”

My grandmother looked dubious.

“Stuff and nonsense,” my grandfather responded.

Nonetheless, Ah Sei persisted with my grandmother, urging her repeatedly to apply a hot iron to what remained of the original eruption. But Ah Mah was indecisive in the light of my grandfather’s dismissal of the notion. There the matter rested.

That mark remained on my right shoulder for decades. It caused me not the slightest irritation or trouble.

But lo and behold! Seventy-three years later, I suffered from another attack of shingles. By then, medical science had advanced to such a degree that viruses could be controlled through medication.

That recurrence does seem to raise an obvious question. Could an illiterate old servant know more about some medical conditions than a modern doctor with university degrees?

I was to experience another horror before the year was out.

Following my arrival in Singapore, my appetite had remained good. Ah Sei’s dishes suited my taste. I would regularly consume two or three bowls of rice with every meal, certainly much more than anybody else in the house. I could have easily done even better on occasions when dishes were to my liking. The trouble was that I did not fill out or put on flesh at all, no matter how much I ate.

My grandmother noted my continuing thinness and consulted my grandfather.

“Probably worms,” Ah Yeh speculated. “Give him a few doses of castor oil.”

When Ah Sei heard that proposal, she suggested an alternative remedy. “No, castor oil no good,” she said. “Bad for system. Better crushed garlic cloves, drunk as extract. Guaranteed effective, since I was little girl.”

The net result was that I ended up having to take both concoctions! They both tasted equally foul. To remove their horrible tastes from my mouth, Ah Sei took to slipping me each time a slice of the liquorice root she used to spice up some of her soups and cooking. I took such a liking to its unique type of sweetness that sucking a piece became almost an addiction, leading later to some quite detrimental effects.

As I have already mentioned, there was only a single toilet in the house. It was a squat toilet shaped like a violin case, with a long porcelain tongue in front leading to the standard pool of water at the rear. In using it, a person should not squat directly over the pool, lest the evacuation splashed water back on one’s bottom. Experience soon dictated that a person should squat a little farther up front, so that the droppings would fall onto the tongue, to be subsequently flushed away.

My purgatives produced their desired effects. I evacuated copiously. But when I looked down upon my faeces, I saw with horror on one occasion a four- or five-inch long roundworm wriggling among the discharge. I was so terrified that I pulled the chain even before I had wiped my bottom.

In the days that followed, I could not bear to look upon what DAVID T. K. WONG I had discharged. The very thought of such parasites alive and wriggling inside my gut gave me a prickly sensation all over my skin.

After those purges, their only visible effect was that I gradually grew taller. Otherwise I remained as skinny as a beanstalk.

Sometime during that first year at Blair Road, my grandmother began taking me to a Sunday school at St Matthew’s Church on Neil Road. The lessons were conducted in Cantonese. In the years that followed, I was to hear again all the parables that I had already heard in Canton. Gradually, I started believing there had to be a more wonderful afterlife if God was merciful. Otherwise, there would be no point putting up with so much suffering in the present one.