Roger Waters succeeded in his application to join the Regent Street Polytechnic’s architecture department and in the summer of 1962 he moved to London. The main college building is on the west side of upper Regent Street but the architecture school was housed in the rather grand annex on nearby Little Titchfield Street complete with St. George and the Dragon over the grand entrance. By this time Roger had a few months work experience in an architectural office and arrived full of self-confidence. He had an ambivalent attitude toward his studies and years later, he unequivocally stated: “I’ve never been interested in architecture.” For whatever reason, he was a poor scholar and after two years he was asked to leave for refusing to attend his History of Architecture lectures.

As with secondary school, Roger blamed his problems with authority on the teachers. “I was very bolshie,” he told Chris Salewicz. “I must have been horrible to teach. But the history lecturer that I came up against was very reactionary, so it was a fair battle. I said I wouldn’t do exams because the guy refused to talk to me. He’d tell us to sit down and copy a drawing off a blackboard. And I asked him if he could explain why, because I couldn’t see the point in copying something off a blackboard that he was copying off a textbook. It was just like school. I couldn’t handle it. I’d hoped I’d escaped all that. When you go to university, you expect to be treated like little grown-ups.”

The practice of the teacher drawing floor plans for the students to copy was a traditional one in architecture and had been practiced at the Poly ever since the place was founded. Roger’s reaction against outmoded tradition was predictable and expected Sixties behaviour; it characterised the decade but Roger’s method of dealing with the situation was not very constructive. By all accounts he had an arrogant attitude and went about with what Nick Mason in his autobiography described as “an expression of scorn for most of the rest of us, which I think even the staff found off-putting.”

Roger first bought a guitar in Cambridge when he was 14, but he gave it up because it was too difficult to learn: “It hurt my fingers, and I found it much too hard. I couldn’t handle it.” He was able, however, to bang out ‘Shanty Town’ to anyone who cared to listen. At the Poly his interest in playing was renewed. Roger: “I invested some of my grant in a Spanish guitar and I went and had two lessons at the Spanish Guitar Centre but I couldn’t do with all that practice.” Using Letraset, a peel-off lettering system used by architects and graphic artists, he had written ‘I believe to my soul’ in neat letters (almost certainly gil sans) across the sound board of his shiny new guitar and presumably varnished it or else it would have rubbed off.

Roger: “The encouragement to play my guitar came from a man who was head of my first year at architecture school at Regent Street Polytechnic, in London. He encouraged me to bring the guitar into the classroom. If I wanted to sit in the corner and play guitar during periods that were set aside for design work and architecture, he thought that was perfectly alright. It was my first feeling of encouragement.” With his new musical confidence he gravitated towards a group of students who wanted to form a band; as in most colleges there is always a room where people meet to play instruments, at the Poly it was the Student Players office where the Poly Drama Club rehearsed. Roger: “At the Polytechnic I got involved with people who played in bands, although I couldn’t play very well. I sang a little and played the harmonica and guitar a bit.”

Roger and Syd had always said that they would form a band together when moving to London.

His first ‘professional’ (i.e. semi-public) gig is listed as playing with fellow student Keith Noble as the Tailboard Two in the assembly hall of the Regent Street Polytechnic School. The name suggests a possible folk or country and western influence on the duo at the time which is intriguing. Though he was working in the same studio as both Rick Wright and Nick Mason, they had been in the same class for about six months, until the spring of 1963, before he got to know them.

Richard William Wright was born on July 28, 1943 to Cedric and Bridie Wright, in Hatch End, the most exclusive end of well-to-do Pinner, one of the 10 hamlets of the medieval Harrow Manor, in what was once rural Middlesex. Cedric was the chief biochemist for Unigate Dairies which enabled them to live comfortably in what had become a pleasant distant suburb of London. Rick’s mother, Bridie, was originally from Wales and he had two sisters, Selina and Guinivere. He was sent first to St. John’s School, an independent day prep school founded in 1920 in Pinner.*

It was a boys school of the traditional type; one of Wright’s contemporaries there remembers being beaten virtually every day for minor infractions by vicious cane wielding masters. At 13 Rick took the common entrance exam and went as a day boy to the Haberdasher’s Aske’s Grammar School, then in Hampstead. The school has occupied many sites since it was founded in 1690 but though it was a direct grant grammar school, it maintained a certain formality: for instance many of the boys wore straw boaters in the summer. Rick was always musical; playing piano and trumpet when very young and at 12 years old he picked up the guitar when he was bedridden for two months with a broken leg. He learned to play without the aid of a tutor, in the manner of the old blues singers, and so used his own fingering and tuning. With the rise of trad jazz in the late Fifties he learned to play both trombone and saxophone and jammed with friends.

Rick was first attracted to classical music but then he encountered jazz on the radio; thanks to the combined efforts of the Musicians Union and the BBC this was white British jazz but interesting enough. He saw Humphrey Lyttelton and Kenny Ball play Eel Pie Island and was present when Cyril Davies introduced R&B to the Railway Tavern in Harrow. Then he discovered Miles Davis.

Wright told Q magazine that his all time favourite record was Miles Davis’s Porgy And Bess: “Porgy And Bess is a brilliant record – the nearest thing to hearing a trumpet being made to sound like the human voice. I have to put this record on from beginning to end, because it stops you dead in your tracks. People might be surprised to hear me being so infatuated with jazz, but the influences in the Floyd came from lots of different areas. Syd was more into Bo Diddley; I had the more classical approach. If I was forced to pick an all-time favourite record, this would probably be it.” Rick stated that he could easily list Miles Davis albums as his 10 favourite records. This positions him alongside many of his generation, including the author of this book, who eagerly awaited the new releases on the Blue Note, Impulse and Riverside labels by John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Horace Silver, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, Art Pepper and all the great albums released in the late Fifties and early Sixties. Nor was it impossible to detect references to Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor or even Albert Ayler in Rick’s wilder moments at UFO, or so I imagined.

Rick did a stint as a delivery man for Kodak, presumably as a summer job, before going to the Poly in September 1962.

Nick Mason also joined the Poly architectural school that year. He, at least, expected to graduate and become an architect even though his real interest was in cars. Nicholas Berkeley Mason was born in Edgbaston, a suburb of Birmingham, on January 27, 1944, to Bill and Sally Mason. He had three sisters Sarah, Melanie and Serena. When Nick was two years old, his father was offered a job with the Shell Oil film unit and the family moved to Downshire Hill, Hampstead, a beautiful street filled with mainly Regency houses that lent its name to a school of artists, including Stanley Spencer and Mark Gitler, who gathered at number 47 between the wars. Running off it is Keats Grove where Keats lived and wrote ‘Ode To A Nightingale’ and at the north end is the Heath itself.

Bill Mason made films about motor sports and used to race himself. Nick first attended a motor race when he was six or seven and has been obsessed with the sport ever since. His father had joined the Communist Party in the Thirties as a way of opposing the growth of fascism and with the outbreak of war he resigned from the party to become a shop steward at the ACT, the Association of Cinematographic Technicians. Both Nick’s parents were staunch Labour Party supporters which was one of the reasons he got on so well with Roger Waters whose mother was also an ex-Communist party member turned Labour Party activist.

Nick began drumming early on, having been given a drum set for Christmas when he was 13 years old after failing both violin and piano lessons. He used it to play in the school Dixieland jazz band. Like other members of the Floyd, and most of his generation in Britain, Nick stayed awake listening to Radio Luxembourg through the waves of static and bought Bill Haley’s ‘See You Later Alligator’ on a fragile 78. He says that not only was Elvis Presley’s 1956 Rock ‘N’ Roll his first LP but it was the first LP bought by two other members of Pink Floyd. The cover now has iconic status with Elvis strumming hard on his acoustic, eyes closed, bellowing away and his name spelled out in green and pink. It summed up everything rock ‘n’ roll was supposed to be about: youth, energy, sex; no wonder it was affectionately copied by the Clash for their 1979 album London Calling.

Pink Floyd loon about outside EMI House, celebrating signing with the Beatles’ label.

Nick soon found other boys in the neighbourhood who were interested in rock ‘n’ roll and by Christmas 1956 he found himself drumming as a member of the Hotrods, a combo featuring Tim Mack on lead guitar, William Gammell on rhythm, Michael Kriesky on bass and John Gregory on saxophone. Sadly their equipment was so embarrassing that for their group photograph they had to mock up a Vox cabinet by drawing knobs on a cardboard box with a Biro. Musically, Mason wrote, they did little more than use Nick’s father’s Grundig tape recorder to record endless versions of Duane Eddy’s summer 1959 hit version of Henry Mancini’s ‘The Peter Gunn Theme’, a television detective series from the late Fifties.

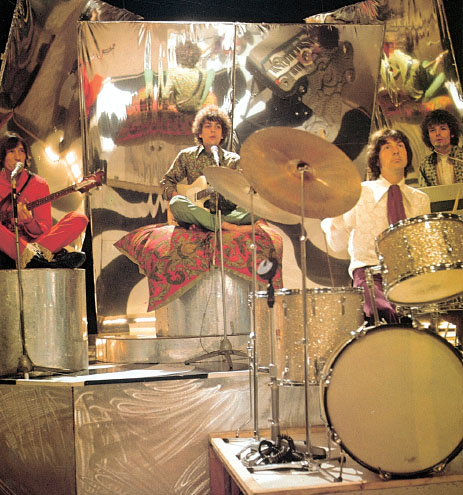

This spread: Pink Floyd rehearsing at Queen Elizabeth Hall, London for the Games For May event, May 1967, which utilised the first full-scale use of stage props.

Pink Floyd promoting ‘See Emily Play’ during one of three consecutive appearances on BBC TV’s Top Of The Pops in 1967.

After prep school, Nick was sent to board at Frensham Heights, a private coeducational school housed in a magnificent Edwardian country mansion near Farnham in Surrey. The school was set up in the Twenties in the liberal tradition and, though it was very academic, it also encouraged individual thought. It was there that Nick met his first wife, Lindy, who came from a similar left-wing background to himself. He enjoyed boating on Frensham ponds in his own canoe, dancing in the grand ballroom of the country house – foxtrots, waltzes, veletas – and later, even hops to pop music. There was only one record player in the school so the jazz club was somewhat restricted in its activities. After a year in London “improving my studies” and attending traditional jazz clubs like Ken Colyer’s and the 100 Club, he entered the Regent Street Poly in September 1962. Nick enthusiastically embraced the student life, wearing corduroy jackets and a duffle coat with bone toggles; he even tried smoking a pipe.

Roger and Keith Noble decided to enlarge the Tailgate Two to be a proper group. Guitarist Clive Metcalfe, another Poly architecture student, had also been dueting with Keith Noble (perhaps also as the Tailgate Two?) and Metcalfe, Waters and Noble now invited Nick to join them in a new ensemble to be known as Sigma 6. The other members, necessary to make it Sigma 6 not the Sigma 4, were Keith Noble’s sister Sheila who sometimes helped out on vocals, and Rick Wright on keyboards. Rick’s situation was difficult because he did not possess an electric keyboard and was therefore only able to enhance the lineup when a pub happened to have a stand-up piano somewhere near the stage, though, as Nick pointed out, no-one could hear him over the Vox AC30s and drums without amplification anyway.

They were sometimes augmented by Rick’s girlfriend, and later wife, Juliette Gale on vocals who was taking Modern Languages at the Poly. She specialised in blues standards such as ‘Summertime’ and ‘Careless Love’ and was apparently very good but she left at the end of their first year – the summer of 1963 – to study at the newly built University of Sussex in Brighton. At the same time Rick switched his studies from architecture to music and transferred to the London College of Music but by now he was an integral part of the group and continued to play with Sigma 6. He had quickly found that architecture was not his metier so, in addition to rehearsing and continuing with his architectural studies, he took a crammer course in order to enter the London College of Music. Rick: “I went to a private school, a dreadful private school, to do theory and composition. That was while I was going to architectural school as well, and after that I went to the London College of Music. Someone used to stand there, and he obviously didn’t beat my hands if I went wrong, but it was a bit of a joke. I used to learn pieces off by heart, and then play them and pretend I was sight-reading, and of course, he caught me out. He said, ‘Right, stop, and go back four bars.’ And I didn’t know where I was.”

Vernon Thompson, a guitarist who could actually play his instrument, joined Sigma 6 briefly but left after a couple of rehearsals, taking his much admired Vox amplifier with him. The few gigs they played were usually for friends: private parties, student dances and the like. This was the time they were experimenting with names, among them the Abdabs, the Screaming Abdabs (in slang, to have a screaming abdab was to have an angry fit and lose control) and the Spectrum Five.

It was as the Abdabs that they gave their first ever interview, to Barbara Walters, writing in the Poly magazine:

“An up-and-coming pop group here at the Poly call themselves ‘The Abdabs’ and hope to establish themselves playing Rhythm and Blues. Most of them are architectural students. Their names are Nick Mason (drums); Rick Wright (rhythm guitar); Clive Metcalfe (bass); Roger Waters (lead); and finally Keith Noble and Juliette Gale (singers).

Why is it that Rhythm and Blues has suddenly come into its own? Roger was the first to answer.

‘It is easier to express yourself rhythmically in Blues-style. It doesn’t need practice, just basic understanding.’ ‘I prefer to play it because it is musically more interesting,’ said Clive. I suppose he was comparing it to Rock. Well how does it compare? Roger was quite emphatic on this point. ‘Rock is just beat without expression though admittedly Rhythm and Blues forms the basis of original Rock.’

It so happens that they are all jazz enthusiasts.

Was there any similarity? I asked.

In Keith’s opinion there was.

‘The Blues is just a primitive form of Modern Jazz.’

It is interesting to learn that Roger was still playing guitar at this point and Rick was also playing guitar in the absence of a keyboard. Most of their time was spent rehearsing in the tearoom in the basement of the Poly. In addition to a dozen or so R&B numbers such as John Lee Hooker’s ‘Crawling King Snake’ they played the Searchers’ 1963 hit, ‘Sweets For My Sweet’, and rehearsed songs written by a friend of Clive Metcalfe, a fellow Poly student called Ken Chapman. Chapman became quite involved with the group, becoming their informal manager and handing out printed cards offering their services, without much luck. His concern was mostly in having a band to play his songs, about which Nick Mason in his autobiography is polite but describes as ‘a little too far on the ballad-cum-novelty side for us’. They did their best to help him but when the numbers were finally performed before music publisher Gerry Bron he was less than impressed. He didn’t like the songs and he liked the band even less. Bron passed and instead started his own Bronze label, managing Manfred Mann, Uriah Heep and Collosseum in order to make his fortune. Shortly after this unsuccessful audition came the long summer break of 1963, after which Keith Noble and Clive Metcalfe left to form their own duo and with Juliette at university in Brighton, she was unable to sing with the group on a regular basis.

While Nick had sensibly, remained in the luxury of his parents’ home, Roger was living just off the Kings Road in a rough flat with no telephone – usual for those days – and no hot water; he used the public Chelsea bathhouse just up the road. Nick would sometimes travel across London to join him at one of his local hang-outs, the Café des Artistes, a basement rock and roll club at 266a Fulham Road, where the Rolling Stones and other young bands gathered and where, in 1965, an embryonic Status Quo had their first residency. Now the two of them decided to share a flat together.

With two of the best musicians gone, Roger, Nick and Rick reformed around Roger and Nick’s landlord, Mike Leonard. Leonard taught at Hornsey College of Art where, in 1962, he had set up their Sound and Light department to experiment with light projections and light machines. Roger and Nick knew him because he was also a parttime art tutor at the Poly. In September 1963 he bought a large high-ceilinged Edwardian house at 39 Stanhope Gardens in Highgate which he set about converting into a ground-floor flat with his own accommodation and art studio above. To help defray his mortgage he rented the newly converted flat to his students. Roger and Nick shared the ground floor front room, which also doubled as their rehearsal room. As they had their equipment permanently set up there it left no room for drawing boards so any architectural study was made doubly difficult.

The neighbours complained, but rather than make his tenants keep the noise down, Leonard joined in himself on piano, even buying a Farfisa Duo electric organ in order to become their keyboard player and for a period the band was known as Leonard’s Lodgers. Leonard’s interest was in finding experimental music that would go with his experiments with light. Mike Leonard’s knowledge of lighting was of great use, but they had few occasions to call on his expertise for live gigs. Roger, however, developed a great interest in Leonard’s light machines and spent many hours working with him at Hornsey College Light and Sound lab. Sometimes, when they felt in need of a protracted rehearsal, they gave the neighbours a break and rented a room in the Railway Tavern in nearby Archway Road. Nick Mason: ‘Mike thought of himself as one of the band. But we didn’t, because he was too old basically. We used to leave the house to play gigs secretly without telling him.’ The year passed with few gigs, a lot of rehearsals and plenty of talk about the future.

‘One day I met a guy called Roger Waters who suggested that when I come up to a London Art School we got together and formed a group.’

Syd Barrett

In September 1964, two friends of Roger’s from Cambridge, Syd Barrett and Bob Klose, moved to London. Klose went to the Poly and Syd to Camberwell Art College to do painting. Roger: ‘They came to live in a flat in Highgate that I was living in. Nick Mason and Rick Wright had lived in it before us. With the advent of Bob Klose we actually had someone who could play an instrument. It was really then we did the shuffle job of who played what. I was demoted from lead guitar to rhythm guitar and finally bass. There was always this frightful fear that I could land up as the drummer.’ To this latter task Nick Mason thankfully responded now that Roger had found his role as a bass player, otherwise he would have finished up as the roadie. In the same interview Waters was talking about a slightly later period regarding the living arrangements: Nick moved back to his parents’ house that summer in order to concentrate on his studies as it was impossible to get any work done in the ground floor flat he shared with Roger. Bob Klose moved in to take his place. Roger’s demotion to bass came about because he refused to use his grant money to buy an electric guitar.

Now all the Abdabs lacked was a vocalist. Bob Klose suggested a friend of his, Chris Dennis, a former member of the Cambridge band the Redcaps who was now serving as a dental assistant in the RAF, stationed at Northolt in London’s western suburbs. Not only could he sing, but he owned a Vox PA system. Nick Mason is very amusing about Dennis in Inside Out, in particular his penchant for introducing numbers as ‘Looking Through The Knotholes In Granny’s Wooden Leg’ and making Hitler moustaches with his harmonica. He was older than the others and had been badly affected by The Goon Show. The band name now alternated between the Abdabs and the Tea Set though the latter, had they kept it, would have inevitably caused problems as the British Tea Board advertised their wares at the time in a series of advertisements calling for the public to ‘Join The Tea Set’ featuring a gormless collection of happy tea drinkers, smiling at the camera with their little fingers crooked.

On November 6, 1963, Syd made a great sacrifice and missed seeing the Beatles play the Regal Theatre in Cambridge in order to attend his interview at Camberwell College of Art for which he borrowed a pair of shoes – with laces – from his girlfriend’s father. Syd’s shoes were always a subject of some amusement to the other members of the band. Roger Waters told John Ladd: ‘Syd used to have elastic bands around his boots ‘cause the zippers were always breaking and you couldn’t get the buttons done up.’ Roger even referred to it in his song ‘Comfortably Numb’.

Syd was offered a place at Camberwell starting at the end of September, 1964. That summer, David Gilmour’s friend from the Perse, Seamus O’Connell moved with his mother to London where she rented a cheap flat in Tottenham Street, just off Tottenham Court Road. At the end of the block was Schmidt’s, the magnificent, huge and cheap German restaurant on Charlotte Street, famous for the rudeness of its waiters, and at the other end was a bomb site on Whitfield Street; London was still rebuilding from the war. It was a perfect central location in what had, before the war, been the bohemian area of Fitzrovia. When Syd and his friend David Gale arrived in town they managed to find a bedsit in the same block. Gale had gone up to Cambridge University but took a year off to enjoy himself in London. He took a job at Better Books, on the Charing Cross Road where one of his colleagues was Adam Ritchie, who later took some of the most evocative photographs of the Pink Floyd at the UFO Club. Syd and Gale’s bedsit was in an apparently terrifying building filled with drunken Irish navvies who filled the night with screams and the sound of breaking glass. It didn’t suit Syd and not long after arriving, he moved out and joined Roger Waters and Bob Klose at Mike Leonard’s house, sharing a room with Roger Waters while Bob Klose shared the other room with another Cambridge associate Dave Gilbert.

Roger: ‘Syd and I had always vowed that when he came up to art school, which he inevitably would do being a very good painter, he and I would start a band in London. In fact, I was already in a band, so he joined that.’ He did not join it immediately. Syd’s priority was painting and it took a while for him to settle into art college routine. He came along to see the Abdabs rehearse. Mike Leonard had opened out the roof space of 39 Stanhope Gardens into an area that was perfect for rehearsals if you didn’t mind humping all the equipment up stairs. They were playing there when Syd arrived late to watch. Afterwards he said, “Yeah, it sounded great, but I don’t see what I would do in the band.”

After Chris Dennis had returned to his RAF base a band meeting was held where it was decided that Dennis should go and Syd should join in his stead. As Bob Klose had hired the singer it naturally fell to him to break the news. He called Dennis from a pay phone in Tottenham Court Road but as it turned out Dennis was being posted abroad and would have had to resign anyway. And so Syd joined the band. As he once described it, in his oblique way: “One day I met a guy called Roger Waters who suggested that when I come up to a London Art School we got together and formed a group. This I did, and became a member of the Abdabs. I had to buy another guitar because Roger played bass, a Rickenbacker, and we didn’t want a group with two bass players.”

Rick Wright: “It was great when Syd joined. Before him we’d play the R&B classics, because that’s what all groups were supposed to be doing then. But I never liked R&B very much. I was actually more of a jazz fan. With Syd, the direction changed, it became more improvised around the guitar and keyboards. Roger started to play the bass as a lead instrument and I started to introduce more of my classical feel.”

Syd: “Their choice of material was always very much to do with what they were thinking as architecture students. Rather unexciting people, I would’ve thought, primarily. I mean, anybody walking into an art school like that would’ve been tricked – maybe they were working their entry into an art school. But the choice of material was restricted, I suppose, by the fact that both Roger and I wrote different things. We wrote our own songs, played our own music. They were older, by about two years, I think. I was 18 or 19. I don’t know that there was really much conflict, except that perhaps the way we started to play wasn’t as impressive as it was to us, even, wasn’t as full of impact as it might’ve been. I mean, it was done very well, rather than considerably exciting. One thinks of it all as a dream.”

Syd Barrett was responsible for writing the Floyd’s two UK hit singles and the bulk of their first album, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn.

By this time – 1964 – Syd and Roger had both begun their careers as lyricists. Syd had already written such numbers as ‘Butterfly’ and ‘Remember Me’ as well as ‘Let’s Roll Another One’ (eventually released as ‘Candy And A Currant Bun’ on the B-side to ‘Arnold Layne’) which showed his early enthusiasm for pot (the words had to be changed before EMI would release it). Roger had written a song, generally thought to be his first ever song, called ‘Walk With Me, Sydney’, inspired by Syd’s new name, and a pastiche of ‘Work With Me, Henry’ by Hank Ballard and the Midnighters (1954) that they would have known from studying old R&B records. It was designed to be sung by Syd and Juliette Gale: Juliette:

‘Ooooh, walk with me, Sydney.’

Syd: ‘I’d love to, love to, love to, baby, you know.’

Juliette: ‘Ooooh, walk with me, Sydney.’

Syd: ‘I’d love to, love to, love to …’

Juliette: ‘Ooh Sydney, it’s a dark night./Hold me, hold me, hold me, hold me, hold me, hold me tight.’

Syd: ‘I’d love to, love to, love to/But I’ve got flat feet and fallen arches, baggy knees and a broken frame/meningitis, peritonitis, DTs and a washed-out brain.’

This was the sort of light-hearted song they would play when they sang on the tube trains to raise money for Student Rag Week. With Syd on board, the line-up was now close to what was to become the Pink Floyd. Though it could easily have not happened. According to Tim Willis, Syd wrote to his then girlfriend Libby Gausden in Cambridge, reporting that a mutual friend had heard him rehearse with the Tea Set and told him that he should give it up because he sounded horrible. Syd told her: “He’s right, and I would, but I can’t get Fred to join because he’s got a group. So I still have to sing.” This letter is an extraordinary find because Fred was the Cambridge nickname for David Gilmour. This makes his replacement for Syd in the Pink Floyd something that they must have first been talking about as far back as 1964. But Syd persevered.

In October 1967 he told Beat Instrumental: “I changed guitars, and we started doing the pub scene…. A couple of months ago, I splashed out a couple of hundred on a new guitar, but I still seem to use that first one (a Fender Esquire Telecaster). It’s been painted several times, and once I even covered it in plastic sheeting and silver discs. Those discs are still on the guitar, but they tend to look a bit worn. I haven’t changed anything on it, except that I occasionally adjust the pickups when I need a different sound.”

Like most colleges, the Poly student union put on regular concerts and dances in the large assembly hall. The dances were usually to records, but sometimes a band would be hired. On these occasions, as the only house band, the Tea Set got to play support. In this way they got to study the mechanics of putting on a professional show: stagecraft, setting up, tuning, loading gear and the rest. They played support to the Tridents, who featured Jeff Beck on guitar, then about to replace Eric Clapton in the Yardbirds. It was in the autumn of 1964 that they finally took the name Pink Floyd, though this was alternated with the Tea Set for many months to come whenever the Pink Floyd was deemed too freaky. The occasion was a gig at the RAF base at Uxbridge where they turned up only to find that the other band on the bill was also called the Tea Set. A new name was clearly in order and it was Syd who provided it.

Syd had two cats, one called Pink, after Pink Anderson, the blues singer from Laurens, South Carolina, who made three albums for Bluesville, and the other called Floyd, after Floyd Council from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He played on several Blind Boy Fuller albums which is how Syd must have known of his work. Syd quickly joined together the names of his cats and produced the name Pink Floyd, though at first they called themselves the Pink Floyd Blues Band. Syd: “During that period we kept changing the name until we ended up with the Pink Floyd. I’m not sure who suggested it or why, but it stuck.”

During the Christmas break they were able to make their first studio recording. Rick had a friend who worked in a recording studio in West Hampstead who let them use some unbooked studio time without charge. They cut Slim Harpo (James Moore)’s ‘I’m A King Bee’ and three of Syd’s compositions: ‘Double O Bo’ – described by Nick as ‘Bo Diddley meets the 007 theme’ – ‘Butterfly’ and ‘Lucy Leave’.* They pressed up a limited number on acetates but usually sent out reel-to-reel tape copies (the Phillips cassette recorder did not come on the market until 1964 and was not yet in wide use) to prospective venues. It was also at this time that Rick sold his first song, receiving a £75 advance against royalties for ‘You’re The Reason Why’ which appeared on the B-side of a 1964 Decca single, ‘Little Baby’ by Adam, Mike and Tim, a Liverpudlian folk-pop harmony group. Sadly, it bombed.

In the spring of 1965 they played their first residency; at the Countdown Club in the basement of 1A Palace Gate off Kensington High Street. Each Friday night they performed three 90 minute sets, beginning at 9 pm and ending at two in the morning* for a fee of £15. Playing such long sets meant that, in addition to learning a lot of new numbers, they quickly realised that the time could also be filled by long improvised solos. Although the band had about 80 songs in their repertoire – a mixture of R&B, Bo Diddley and Rolling Stones numbers – Nick remembers only two items from their set: a novelty number, ‘Long Tall Texan’ (originally recorded by Jerry Woodard and recently covered by the Beach Boys on their 1964 Concert album) and Bob Klose’s showcase, ‘How High The Moon’. Though it was set up for music, the Countdown was not soundproofed and after only two or three weeks, the neighbours served the club with a noise injunction. As this was their only paying gig, the band even offered to play acoustically. The club had an upright piano for Rick, Syd and Bob Klose strummed acoustic guitars, Nick used wire brushes like a proper lounge act and Roger somehow managed to find an upright double bass.

The Pink Floyd were hard to see because of their light show, which meant that even when they were famous they were rarely bothered by fans on the street.

Klose had been falling behind with his studies and both his father and his tutors blamed his failing grades on the band. When he failed his first year exams his father told him: ‘No more music, you must study now’ and that was the end of his career with the Pink Floyd. Though he played a few surreptitious gigs with them, he could no longer practice at college or play at college gigs. The band lost their most accomplished musician which essentially meant that they could no longer hope to remain an R&B band; they were not good enough players. The band’s activities had also affected Roger’s studies and he was held back a year. The staff thought he needed practical experience before going on to the next stage and arranged for him to work in an architectural practice. Nick, meanwhile, headed off to Guildford to do a year’s work experience in the architectural offices of Frank Rutter, the father of his girlfriend Lindy, and appears to have enjoyed it. In his book he shows a lot of respect for Rutter, both as a person and as an architect. The practice was in Rutter’s family house in Thursley, south of Guildford, which was large enough to house his staff and also accommodate his family and friends, including Nick. The large grounds enabled the staff to play croquet on the lawn during their lunch break.

The band were sometimes hired for parties out of town and at one such, the 21st birthday party of Libby January, Storm Thorgerson’s girlfriend, in Cambridge, they found themselves sharing the bill with Joker’s Wild which may have been the first time that Nick and Rick met the Joker’s lead guitarist and vocalist, David Gilmour, unless they previously met when the London band members came up to visit; Nick is known to have enjoyed weekend visits to Roger’s mother’s house. Gradually, inexorably, the band was getting itself together.