At the Spontaneous Underground held on 13 June 1966, the Pink Floyd met their future manager Peter Jenner, an assistant sociology lecturer at the London School of Economics and one of the people involved with starting the London Free School. Peter was a great follower of experimental music and was one of the founders of DNA Productions, set up to record avant garde jazz and so-called modern classical music by John Hopkins, Felix de Mendelsohn and two jazz critics Ron Atkins and Alan Beckett. Their first production had been AMMMUSIC by AMM released by Hoppy’s friend, the American tour promoter and producer Joe Boyd, who now worked for Jac Holzman at Elektra Records. Next they recorded an album with American Steve Lacy, but it was not released, possibly because when they analysed the deal with Elektra – the standard 2% production royalty – they realised that they would have to sell tens of thousands of records in order to make any money after recording costs. The only way to make money as producers was to have a hit record and that meant rock ‘n’ roll. Peter began searching for a band to produce, he wanted something challenging but more commercial than the music he had already recorded.

Earlier that summer, Kate Heliczer returned to Britain having spent some time living in New York as part of Andy Warhol’s downtown Factory scene. She knew Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga and Lou Reed and brought with her tapes of the Velvet Underground playing at Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Peter was very impressed with the tapes, but by the time he got through to John Cale on the phone, Warhol had decided to go into record production himself and had already recorded the Velvets. It was a Sunday in June and Jenner was fed up with marking exams so he decided to call it a day and wander down to the Marquee to see what was going on at the Spontaneous Underground.

“I arrived around 10:30,” he recalled, “and there on stage was this strange band who were playing a mixture of R&B and electronic noises. In between the routine stuff like ‘Louie Louie’ and ‘Road Runner’ they were playing these very weird breaks. It was all very bizarre and just what I was looking for – a far out, electronic, freaky pop group … and there, across their bass amp was their name: ‘The Pink Floyd Sound.’” Jenner was puzzled by the sounds the group were making; he couldn’t figure out if they were coming from the organ or the guitar. Syd was using a Binson Echorec, an echo unit, probably the B2 introduced in 1962, and most celebrated by being used by Hank Marvin of the Shadows.* It had twelve settings and two foot pedal sockets, giving him an enormous range of possibilities of sound, particularly when he used his zippo lighter as a plectrum.

Rick Wright: “That was a very special time. Those early days were purely experimental for us and a time of learning and finding out exactly what we were trying to do. Each night was a complete buzz because we did totally new things and none of us knew how the others would react to it. It was the formation of the Pink Floyd.”

The Floyd celebrate Syd’s 22nd birthday in a photo shoot for Fabulous 208 magazine, January 1968.

Jenner realised that he could not manage a band by himself and discussed it with his old school friend Andrew King, an educational cyberneticist, who had recently left his job at the British Airways training and education department and was at a loose end. King agreed to become his partner and together they visited Mike Leonard’s house in Stanhope Gardens and offered to manage them. Roger Waters described their meeting: “As far as I remember he must have come to a gig, maybe it was one of those funny things at the Marquee. But he and Andrew King approached us and said, ‘You lads could be bigger than the Beatles!’ and we sort of looked at him and replied in a dubious tone ‘Yes, well we’ll see you when we get back from our hols,’ because we were all shooting off for some sun on the Continent.”

Roger was going to Greece with a group of friends including Rick Wright and it was there he took acid for the first and only time. He didn’t have a bad time, but found the experience so powerful that he felt no need to repeat it. In those days it was common to take massive doses, usually in liquid form where there was no accurate way of measuring the amount. He told John Harris: “I took it and thought I was coming out the other end, and went to the window in the room where I was – and I stood on the spot for another three hours. Just frozen.” This was probably also the time when Rick Wright first took it.

Nick Mason was already away, having gone to New York where his girlfriend Lindy was training with the Martha Graham Dance Company. He saw the Fugs play the Players Theatre on Bleeker Street and both Mose Allison and Thelonius Monk at the Village Vanguard, then he and Lindy bought two of the famous $99 unlimited travel Greyhound tickets and set out to explore America, visiting San Francisco and even going down to Mexico City and spending time in Acapulco where hotel rooms were only a dollar a night. After three months they returned to New York. Nick had not thought much about the Pink Floyd while he was away, in fact when he left the band had been on the point of breaking up; gigs were hard to come by, they had no proper equipment, and rehearsals were interfering with their studies. He thought that on his return to London he would be once more immersed in his architectural studies.

Tickets for the launch party for International Times at the Roundhouse.

Then, in New York, he bought a copy of the local underground newspaper, the East Village Other, or EVO as it was known, with a report on the London underground scene that mentioned the Pink Floyd Sound as the most interesting of the new bands. In Inside Out, A Personal History of Pink Floyd, he wrote: ‘Finding this name check so far from home really gave me a new perception of the band. Displaying a touchingly naïve trust in the fact that you can believe everything you read in the newspapers, it made me realise that the band had the potential to be more than simply a vehicle for our own amusement.’

I was the London correspondent for EVO and I am proud to say that I was the author of this piece which was, oddly enough, the first press coverage the Pink Floyd ever had outside the Poly student paper. It is even nicer to feel that it may have helped encourage the band to stick it out though this was much more down to the efforts of Peter Jenner and Andrew King. Seeing that they were serious about managing them, and providing them with new, much needed equipment, the band agreed to let them manage them, though Roger and Nick secretly thought that Jenner and King were drug dealers.

Though Syd was already smoking pot and writing songs, it was not until 1966, when he was 20, that he took his first trip.* Syd, along with Storm Thorgeson, Nigel Gordon and Ian ‘Imo’ Moore, was visiting his friend Bob Gale in his garden in Cambridge. Thorgeson and Imo had laid out hundreds of sugar cubes in rows and were treating each one with two drops of liquid LSD from a glass bottle. The acid was very concentrated and as they licked the sugar granules from their fingers they became hopelessly confused, giving some cubes a double dose and others none at all. Imo has often told the well known story of how Syd found three objects: an orange, a plum and a matchbox and sat and stared at them for twelve hours. The plum became the planet Venus and the orange was Jupiter. Syd travelled between them in outer space. His trip came to an abrupt end when Imo, feeling hungry, ate Venus in one bite. “You should have seen Syd’s face. He was in total shock for a few seconds, then he just grinned.”

Nigel Gordon: “We were all seeking higher elevation and wanted everyone to experience this incredible drug. Syd was very self-obsessed and uptight in many ways so we thought it was a good idea. In retrospect I don’t think he was equipped to deal with the experience because he was unstable to begin with. Syd was a very simple person who was having very profound experiences that he found it hard to deal with.”

Syd and his new co-manager Jenner spent the summer of 1966 listening to Love’s eponymous debut album and Fifth Dimension by the Byrds. This gave rise to one of the Pink Floyd’s most emblematic numbers, ‘Interstellar Overdrive.’ Jenner had tried to hum Arthur Lee’s guitar hook from Love’s version of Burt Bacharach’s ‘My Little Red Book’ to Syd, but what Syd played back sounded quite different and he used the chord changes to write ‘Interstellar Overdrive.’ Jenner and Barrett also took a lot of acid together and became very close.

Though the Pink Floyd became the symbol of psychedelic music in Britain, the other members of the group were more reserved, and had little to do with drugs. In fact Nick Mason didn’t even regard Syd as part of the underground scene: “I don’t think Syd was a man of the times. He didn’t slot in with the intellectual likes of John Hopkins and Joe Boyd, Miles, Pete Jenner, the London Free School people. Probably being middle class we could talk our way through, make ourselves sound as though we were part of it…. But Syd was a great figurehead. He was part of acid culture.”

This was one of the biggest differences between the British and American West Coast scenes: in San Francisco bands like the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane lived communally in Haight-Ashbury and contributed to the psychedelic community. In Britain, though many individual band members were sympathetic to what was happening on the underground such as Pete Townshend, none of the major bands were actually part of the community (except Hawkwind, later). There were very few benefits or free concerts and, perhaps more importantly, no money funding the community from that source. The Pink Floyd, with the exception of Syd, had barely an inkling of the community who had embraced and supported them. Roger: “You’d hear about revolution, but it was never terribly specific. I don’t know … I read International Times a few times. But, you know, what was the Notting Hill Free School actually all about? What was it meant to do?”

In order to find out, he would have had to get involved and maybe even contribute something himself, but the band were too concerned with becoming pop stars for that. The underground was a convenient stepping stone, to be used and discarded. People who compare the Floyd’s role in the London scene with that of the Dead or Jefferson Airplane in San Francisco are sadly deluded; in reality the Floyd were neither psychedelic nor underground; as they were very quick to point out once they signed with a major record company.

At this time, the Pink Floyd was still, as it were, a straight band. Nick Mason: “At that time we were aiming to be a hit parade band. I mean – we wanted a hit single. The idea of making an album hadn’t even … well, I’m speaking personally, ‘cause I can’t speak for the others, but I suspect that we hadn’t really considered the sort of move onto an album. We were only interested in making a single initially, and a hit single. We were interested in the business of being in rock’n’roll, and being a pop group: SUCCESSFUL – MONEY – CARS, that sort of thing. Good living. I mean, that’s … umm, that’s the reason most people get involved in rock music, because they want that sort of success. If you don’t, you get involved in something else.”

London Free School flyer and an early issue of IT.

Despite their pop aspirations, a company was set up much more in the spirit of the time called Blackhill Productions, named after a cottage that Andrew King had bought in the Brecon Beacons of Wales with a small inheritance. The shareholding was split six ways, giving each of them, managers and band, a one sixth share in the company. This was an extraordinary arrangement when you consider that a typical deal at the time was like Brian Epstein’s with the Beatles: he took 25% off the top before any of the massive expenses – including his own – were paid, and the Beatles divided what was left between the four of them, making him far wealthier than any of them.

King spent the remainder of his legacy on equipment and the band began rehearsing. The equipment was almost immediately stolen and new amps had to be bought on hire purchase. In the interim, Peter Asher, of the pop duo Peter and Gordon, who was a partner in the Indica Gallery and Bookshop and possibly knew Peter Jenner and Andrew King from Westminster school, lent them his backing band’s equipment.

Unfortunately neither King nor Jenner knew anything about booking gigs but just then, two requirements happened to coincide fortuitously. One was the Pink Floyd Sound’s need to perform and the other was that the London Free School needed to raise money. It was John (‘Hoppy’) Hopkins who thought of the idea of a benefit concert, but as both Peter and Andrew were vicars’ sons, it seems likely that it was one of them who came up with the idea of holding it in a church hall; they must have had plenty of experience of such events in their childhood.

‘Those were halcyon days. He’d sit around with copious amounts of hash and grass and write these incredible songs. There’s no doubt they were crafted very carefully and deliberately.’

Peter Jenner

All Saints Hall, on Powis Square (though advertised as being on Powis Gardens) was a traditional church hall – high ceiling, wooden floor, multi-purpose stage at the far end – and possibly not what the Floyd were expecting as a venue. However all went well. In fact, if UFO was the Pink Floyd’s Cavern Club, then All Saints Hall was their Star Club, albeit a very truncated version in terms of time, in both cases.

The evenings were called ‘Sound Light Workshops’ and the Pink Floyd took this seriously. I described one of their sets – using the breathless, underground style of the time – as taking “musical innovation further out than it had ever been before, walking out on incredibly dangerous limbs and dancing along crumbling precipices, saved sometimes only by the confidence beamed at them from the audience sitting a matter of inches away at their feet. Ultimately, having explored to their satisfaction, Nick would begin the drum roll that led to the final run through of the theme [to ‘Interstellar Overdrive’] and everyone could breathe again.’

The first event, on September 30, 1966, was not very well-attended, in fact there were so few people that at one point Syd entertained the audience with the soliloqy from Hamlet, but word soon got around. Notting Hill was then the centre of London’s underground, counter-cultural hippie scene, and the London Free School was central to what was happening. Two weeks later the Floyd played All Saints Hall again and the place was more or less full. Hoppy’s mimeographed flyer read:

ANNOUNCING; POP DANCE FEATURING LONDON’S FARTHEST-OUT GROUP THE PINK FLOYD IN INTERSTELLAR OVERDRIVE STONED ALONE ASTRONOMY DOMINI (an astral chant) & other numbers from their space-age book also: LIGHT PROJECTION SLIDES LIQUID MOVIES THE TIME: 8-11 PM THE DAY: FRIDAY 14 OCTOBER THE PLACE: ALL SAINT’S HALL, POWIS GARDENS, W11 THE REASON: GOOD TIMES ANOTHER LONDON FREE SCHOOL PRODUCTION.

The last of the Pink Floyd Sound Light Workshops at the London Free School, held on November 29, was reviewed for International Times by the Soft Machine’s original Californian lead guitarist, Larry Nolan: “Since I last saw the Pink Floyd they’ve got hold of bigger amplifiers, new light gear and a rave from Paul McCartney … Their work is largely improvisation, and lead guitarist Syd Barrett shoulders most of the burden of providing continuity and attack in the improvised parts. He was providing a huge range of sounds with the new equipment, from throttled shrieks to mellow feedback roars. Visually the show was less adventurous. Three projectors bathed the group, the walls and sometimes the audience in vivid colour. But the colour was fairly static, and there was no searching for the brain alpha rhythms, by chopping the focus of the images. The equipment that the group is using now is infant electronics; lets see what they will do with the grownup electronics that a colour television industry will make available.’*

Each LFS concert featured bigger and better lights. The first time they played there, an American couple, Joel and Toni Brown, who had arrived in London from the League for Spiritual Dioscovery, Timothy Leary’s psychedelic centre in Millbrook, New York, showed up with a slide projector and projected strange images onto the band in time with the music. It was rudimentary but both the band and their management reacted enthusiastically. It was the obvious complement to their long improvisations and, as news was already filtering in about bands using light shows in San Francisco, it seemed to be the next big thing. Peter Jenner and his new wife Sumi immediately set to work to build their own lighting rig for the band. It consisted of a row of ordinary spotlights mounted on a board with sheets of different coloured Perspex in front of them, each one operated by an ordinary household on-off switch. They were low powered but threw a huge shadow behind each member of the band which was very effective. Then Joey Gannon got involved. He was only 17 at the time but he knew people at the Hornsey College of Art Light/Sound workshop founded by Mike Leonard, and introduced a projector to the set-up.

Syd was now living at 2 Earlham Street with Peter Wynne-Willson who worked at the New Theatre in the West End and had easy access to discarded theatrical lighting equipment which he renovated for the band. Peter and his girlfriend, Susie Gawler-Wright, became the Pink Floyd light-operators alongside Joey Gannon. Joey brought in some theatrical spotlights that he operated using a small keyboard built by Wynne-Willson. He also obtained a 500 watt and a 1000 watt projector. Wynne-Willson developed a way of painting blank slides with brightly coloured inks which became the liquid slides most associated with the London underground scene: he would heat the ink with a small blow torch and cool it with a hair dryer causing the ink to bubble and move. The team experimented with different chemicals and colours and each gig revealed new images and effects as they developed their techniques.

The flat at 2 Earlham Street, was just off Cambridge Circus on the edge of Soho in a row of low run-down old buildings (now demolished) dating back to before Shaftesbury Avenue was built. It was easily identifiable by its purple door. The street was lined with barrows selling used books, an adjunct to the bookshops on Charing Cross Road around the corner. Bargains were still to be found on Earlham Street and it was thronged with book runners, all looking for W.H. Auden’s first book Poems, a copy of which had been found there in 1965 at the cost of one shilling and sold later that day to another dealer for a thousand pounds.

The flower and vegetable markets were still in Covent Garden at the time so it was possible to eat very cheaply on cast-offs or from the stalls in the market. The building was rented by Peter Wynne-Willson and Susie Gawler-Wright who, in the usual Sixties underground style, shared it with a group of ever changing roommates. Susie, with her long straight hair, and slender figure looked the archetypal ‘hippie chick’: “Wow” was her favourite word, said with an air of amused astonishment. She became known as the ‘psychedelic debutante’ as she apparently came from an aristocratic background. She famously featured on the front cover of International Times issue 11, naked except for psychedelic body paint.* Peter Wynne-Willson was also from an elevated background: his uncle was the Bishop of Bath and Wells and lived in a palace surrounded by a moat with swans.

Susie was a follower of Radha Soami Satsang, also known as Sant Mat, an Indian religious cult. This was a method of ‘God-realisation’ consisting of three parts: simran, or the repetition of the Lord’s holy names. The second is dhyan, or contemplation on the immortal form of the Master. This keeps the student’s attention fixed at the centre. The third is bhajan, or listening to the Anahad Shabd or celestial music that is constantly reverberating within us. This was perhaps what appealed to Syd Barrett; apparently, assisted by this divine melody, the soul ascends to higher regions to finally reach the feet of the Lord. Significantly Sant Mat took no money from its followers, unlike some of the Eastern organisations that grew in popularity with the hippies. Though Susie, Nigel Gordon and other Cambridge friends were initiated and given a secret mantra, Syd, inexplicably, was refused. The Maharaj Ji Charan Singh, famous for initiating the largest number of seekers in the history of Radhasoami, told him that, as a student, he should first of all complete his studies before devoting his life to the divine path. Syd applied twice, and was twice rejected, perhaps because the guru could sense that Syd was unlikely to adhere to the cult’s strict rules of vegetarianism and abstinence from alcohol and drugs. Syd, who was enormously interested in mysticism, was devastated.

Among the changing occupants of the various floors at Earlham Street were David Gale, and artist John Whiteley, a friend of Storm Thorgerson, who did the marbling on the front sleeve of A Saucerful Of Secrets. Also living there were Cambridge friends Sue Kingsford, whom Syd knew from Cambridge Tech, and her husband Jock. They were known as Mad Sue and Mad Jock Kingsford, a sobriquet given them for their zealous use of LSD. Syd persuaded his Cambridge girlfriend, fashion model Lynsey Korner, to come and live with him and, at least for a while, everything was looking good for Syd. The final occupant was Syd’s new cat named Rover.

A Saucerful Of Secrets was released in 1968.

Syd’s room was on the top floor, with access to the roof. He dragged a double mattress up the stairs and laid cheap straw matting. As was almost obligatory in those days, the bed was covered with an Indian print from Indiacraft which was also the source of the strings of beads and brass bells. There was a record player and a stack of albums: as American imports became available in 1966 he added Freak Out, the Mothers of Invention’s first album, and The Fugs on ESP, both of which he bought at the Indica bookshop over at 102 Southampton Row who ordered them in from New York. Also among the albums were classic blues artists and rock including the Beatles, the Byrds, and Love. A large brown paper bag had been blown up to use as a lampshade, there was an easel erected by the window which faced north and a guitar leaned against the wall; it was a classic bohemian pad. There was a cheap café just across Cambridge Circus at 20 Old Compton Street called the Pollo Bar and Restaurant (still there as this is written) where he took most of his meals and when the weather was fine he could sit on the flat roof and smoke a joint, strum his guitar and look out over the rooftops of Covent Garden as if he were in the Latin Quarter of Paris.

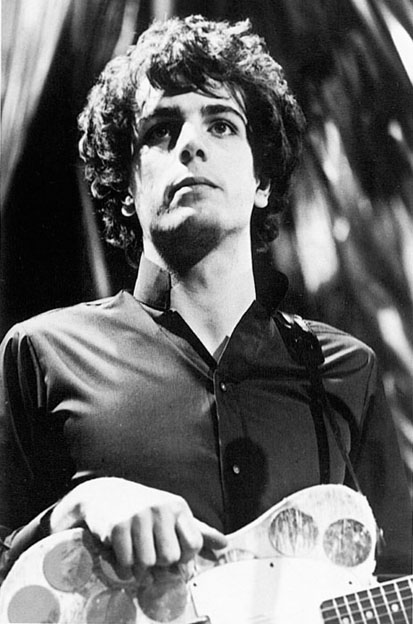

Syd as psychedelic hero on Top Of The Pops, 1967.

This was Syd’s most creative period. Jenner told Robert Sandall: “The strongest image I always have of Syd is of him sitting in his flat in Earlham Street with his guitar and his book of songs, which he represented by paintings with different coloured circles. I was an immense Syd fan. You’d go round to Syd and you’d see him write a song. It just poured out.” Wynne-Willson also remembers this as Syd’s creative peak: “Those were halcyon days. He’d sit around with copious amounts of hash and grass and write these incredible songs. There’s no doubt they were crafted very carefully and deliberately.”

Whereas Syd began the year relatively straight, he was very undisciplined. His mother’s pampering meant that he never placed any restraints on his behaviour, having always been told he was wonderful and special, so once he discovered the drug scene he jumped in feet first. Initially this only meant smoking pot, which he did a lot of, often with Peter Jenner: ‘None of them did drugs when I met them, except Syd, and he would only smoke dope. Then with the Summer Of Love and all that bollocks, Syd got very enthusiastic about acid, and got into the religious aspect of it, which I never did. The others were very straight. They were much more into half-a-pint of bitter than they were into drugs. One of the reasons I got on with Syd was because he and I used to smoke a lot of pot together. Rick would take a puff now and again, but Roger and Nick would never go near it. Syd was very much the artist, while the other two were the architects, and I think that’s an important way of looking at what happened. Syd did this wild, impossible drawing, and they turned it into the Pink Floyd.”

There is no doubt that Syd had a number of life-changing experiences at Earlham Street, mostly involving music, one of which is described by Alan Beam in his autobiography, Rehearsal For The Year 2000 where Peter Wynne-Willson and Susie Gawler-Wright are known as John and Anne: “I went with John and Anne and half a dozen others to watch Handel’s ‘Messiah’ at the Albert Hall with all of us tripping, having lined up beforehand to have two drops of LSD each on the tongue.” For Willson it was “quite the most extraordinary thing I’d ever encountered,” but Beam didn’t fare so well: “On that trip I felt very miserable back at Earlham Street, and too shy to accept when Anne invited me to join them in drawing pictures on the wall.” (This was a popular hippie activity; somewhat frowned upon by landlords).

Syd also liked to drop acid and play John Coltrane’s 1965 masterpiece ‘Om’. It was this type of intense musical experience he was hoping to create with his own earsplitting feedback and chopped up time signatures. In many ways Syd was a precursor of the minimalist movement. He could have easily fitted in with future New York ‘No Wave’ guitarist Glenn Branca; as Andrew King stated, “Given the chance, Syd would have jammed the same chord sequence all night.”

There was no room to rehearse at Earlham Street or where Roger, Rick and Nick lived so band rehearsals were held at 101 Cromwell Road where Roger had lived after leaving Mike Leonard’s flat. 101 was a regency building virtually next door to the West London Air Terminal where, in those days, you would check your luggage in before boarding an airline bus to London (Heathrow) Airport. 101 was a centre of underground activity, much of it to do with drugs. The ground floor flat was occupied by Nigel and Jenny Lesmoire-Gordon, friends of Syd’s and Roger’s from Cambridge who had moved to London in order for Nigel to become a film-maker. Living in a sort of hut constructed in their corridor was the poet John Esam, a tall, thin, spiderlike New Zealander with jet black hair, slicked back like the wings of a beetle.

John was a great proselytizer of LSD – which was then still legal – and aside from Michael Hollingshead’s World Psychedelic Centre in Pont Street, which had been set up by Timothy Leary John was the main source of acid in London. It was dangerous to visit his flat because people had been known to find themselves on a trip after eating an orange or drinking juice from the fridge; perhaps the origin of the stories that Syd’s flatmates were feeding him acid. He certainly visited this flat a lot and eventually moved to a room upstairs in the building.

A friend of Esam’s arrived from the States with several thousand trips for him, but had been followed by the police. John threw a bag of acid-laced sugar cubes into the garden but the police were waiting and caught it, expertly. The police arrested John but then found that LSD was still legal. In order to find a charge that would stick, they then claimed that the substance was ergot, the material acid is made from. They charged Esam under the Poisons Act (manufacturing poison carries an unlimited sentence) and the case went to the Old Bailey. The police were, in essence, trying to prove that LSD was ergot which as Steven Abrams – founder of the drugs research organisation SOMA – pointed out, was like saying that if you boiled instant orange juice, you would wind up with an orange. The prosecution brought over Dr. Albert Hoffman, the discoverer of LSD, from Basel to testify that LSD counted as ergot under the Poisons Act. Esam’s team brought in Dr. Ernst B. Chain, the co-discoverer of penicillin with Sir Alexander Fleming, who maintained that LSD was not in fact made from organic ergotomine but a semi-synthetic derivative. The arguments were so complex that in the end the scientists got together in a huddle, told the judge to wait, and eventually concluded that LSD was not ergot and therefore John was innocent. The experience freaked Esam out to the extent that at least a decade passed before he would even smoke a joint.

At that time, one of the residents at 101 was the painter Duggie Fields. Though the flat’s main connection was Cambridge through Nigel and Jenny, Roger Waters knew Duggie from the brief period Fields spent at the Regent Street Poly studying architecture before going on to the Chelsea School of Art in September 1964. It was probably through Roger that the Pink Floyd got to rehearse at 101 because he moved into part of the maisonette on the top two floors after leaving Mike Leonard’s house in Highgate before finally moving on to live with his girlfriend in Shepherd’s Bush.

Duggie Fields: “They used to rehearse in the flat and I used to go downstairs and put on Smokey Robinson as loud as possible. I don’t know where they all arrived from, but I went to architecture school so did Rick and Roger. I don’t quite remember how I met them all. I just remember suddenly being surrounded by the Pink Floyd and hundreds of groupies instantly.”

The “hundreds of groupies” is something of an exaggeration; this didn’t happen until the group began to play the UFO Club, but the high volume was certainly true. I remember visiting John Esam there at the time and we eventually had to go outside to a café in order to talk because the volume was so loud from their rehearsal that we couldn’t hear each other speak.

THE IT LAUNCH PARTY AT THE ROUNDHOUSE STRIP?????HAPPENINGS//////TRIP//////MOVIES Bring your own poison & flowers & gas-filled balloons & submarine & rocket ship & candy & striped boxes & ladders & paint & flutes & ladders & locomotives & madness & autumn & blowlamps & POP/OP/COSTUME/MASQUE/FANTASY/LOON/BLOWOUT/DRAG BALL SURPRISE FOR THE SHORTEST/BAREST COSTUME.

The Albert Hall Beat poetry reading in the summer of 1965 had identified a community of like-minded people, many of them creative in one way or another, many of them interested in drugs, most of them young. Hoppy and I were very impressed with the energy and enthusiasm of these people and wondered what we could do to bring them together. We envisioned a newspaper, something along the likes of New York’s Village Voice – there were no underground newspapers yet – and to this end Hoppy bought a sit-up-and-beg offset litho press and began experimenting with zinc plates. The flyers for the London Free School and the four issues of The Grove, the newspaper of the LFS were printed on this, as well as a literary magazine called Long Hair featuring a lengthy extract from Allen Ginsberg’s journals (he also named the magazine).

Next we did something called the Global Moon Edition Long Hair Times, designed to be sold on the CND Aldermaston march of Easter 1966. It was simply stapled together like a poetry magazine but it was the forerunner of International Times (IT), the London underground newspaper – and the first underground newspaper in Europe – that Hoppy and I, and a dozen other people, published on October 14, that year.

‘In fact it didn’t even cover her bottom; this must have been the shortest of the evening, if not the barest.’

New Society

IT was launched with a late night party on October 15, 1966, at the Roundhouse in Camden Town. This beautiful building originally housed the winding gear that pulled trains up the hill from Euston station but as soon as engines became more powerful it had had its day and became simply Engine Shed 1B. Gilby’s Gin then used it as a bonded warehouse, constructing a giant circular wooden balcony to house the vats of gin, but by the time of the IT launch even this had become unsafe to walk on. The TUC Congress had passed a resolution to set up a workers arts centre, resolution 42, and playwright Arnold Wesker set up Centre 42 in order to create a workers paradise within the circular walls of the Roundhouse. But he first needed to raise about £380,000 to do it so the building sat cold and empty. IT’s accountant, Michael Henshaw, was also the accountant for Centre 42 and for Wesker himself. It was easy for him to get the keys and Wesker, thinking it was some form of book launch, wished us well.

The floor was thick with a century of dirt; in fact there may not even have been a proper floor, just equipment housings. Twisted iron jutted up from bits of broken concrete. People formed an enormous line outside; the only way in was up a very long narrow single-file staircase. It was so narrow that no-one could leave while other people were coming up, it was impossible to squeeze past. At the top, myself, Hoppy, and David Mairowitz handed out sugar cubes as we took the tickets. They were just sugar cubes but some people used them as an excuse to loosen up and dance wildly. You needed to because it was mid October and very cold. There was no heating and the Roundhouse was not insulated; the wind whistled beneath the loading doors onto the freight yards beyond. There were two lavatories which immediately flooded out, causing such huge puddles that the doors were removed and used as duck boards, and guards stood at the doors to shield the users from the gaze of the long queues waiting to wobble across the wonky boards. It was described in the press as a firetrap, but the main entrance was from the freight yards where there were several enormous doors for locomotives to get in. These were each manned, and were, of course, used by the bands to drive their vans in. We also had a medical doctor, Dr. Stuart Montgomery, publisher of the Fulcrum Press, on hand for emergencies.

There was a giant jelly that the Pink Floyd either did or did not run into with their van. I was there but I don’t remember what happened; the most likely story is that Po, their roadie removed an important piece of wood to use in his setting up and the whole jelly, which was not yet perfectly set, tore loose from its tarpaulin mold. Daevid Allen described the launch as “one of the two most revolutionary events in the history of English alternative music and thinking. The IT event was important because it marked the first recognition of a rapidly spreading socio-cultural revolution that had its parallel in the States. It was its London newspaper. The New Year came … bringing and inexpressible feeling of change in the air.” Daevid remembers two stages whereas there was not even one; the bands played from the bed of an old wooden horse wagon left behind by Gilby’s Gin which had white sheeting draped behind it for the lightshow.

To emerge from the steep narrow staircase into the psychedelic light show that filled the dome of the Roundhouse with coloured blobs and patterns was an extraordinary experience. Binder, Edwards and Vaughan brought along their Fifties Cadillac painted in psychedelic patterns. Films by Kenneth Anger, William Burroughs and Antony Balch were projected on a sheet hanging from the balcony where the gin vats had been. Dutch couple Simon Postuma and Marijika Koger, later known as The Fool, told tarot cards in a fortune telling tent, from which billowed great gusts of incense. Paul McCartney wandered around dressed as an Arab to avoid recognition but, as the only Arab there, he inevitably attracted attention. New Society reported that Marianne Faithfull “was wearing what appeared to be a fair imitation of a nun’s habit, which didn’t quite make it to the ground: in fact it didn’t even cover her bottom; this must have been the shortest of the evening, if not the barest.”

Yes, she won the prize for the ‘shortest/barest’. Michelangelo Antonioni (in London to film Blow Up) and Monica Vitti in a stunning short white miniskirt turned people’s heads. Kim Fowley explained to everyone how he had single-handedly started every band then playing on Sunset Strip. There were silver-foil headdresses, third-eye refraction lenses on foreheads, dragoon jackets and bondage gear and lots of glitter dust. The products of the Lebanese State Hashish factory were much in evidence. Soft Machine played first. Their line-up at that time was Daevid Allen (guitar), Kevin Ayers (bass), Mike Ratledge (organ) and Robert Wyatt (drums).

Daevid wrote: “That was our first gig as a quartet. Yoko Ono came on stage and created a giant happening by getting everybody to touch each other in the dark, right in the middle of the set. We also had a motorcycle brought onto stage and would put a microphone against the cylinder head for a good noise.”

Then the Pink Floyd climbed onto the rickety old cart – it was all reminiscent of Elvis on the Louisiana Hayride – and their fans from the All Saints Hall gigs pushed the loon dancers out of the way to stand at the front. IT reported: “The Pink Floyd, psychedelic pop group, did weird things to the feel of the event with their scary feedback sounds, slide projections playing on their skin (drops of paint ran riot on the slides to produce outer-space/prehistoric textures on the skin), spotlights flashing in time with the drums.” The majority of the audience had never seen a light show before and many stood staring open-mouthed as the amoeba-like bubbles of light pulsated and fused together in time to the music or expanded and blew apart into dozens of offspring.

The Floyd could not have had a more sympathetic audience and they responded with a brilliant set. The Roundhouse electricity supply was as decrepit as the rest of the building and when the Floyd cranked up the volume for the end of ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ they were suddenly plunged into darkness as the fuses blew, providing an unintentional but dramatic climax to their act. Light and sound was soon restored and I went to pay the groups for their fine work. I had to push my way through a crowd of fans, most of them converted in the last hour, before I could reach them. The Soft Machine received £12.10.0 and the Pink Floyd got £15.0.0 because they had a light show to pay for.

The poet Kenneth Rexroth, the poet, anarchist, scene-maker – he was the MC at the famous first reading of Ginsberg’s Howl – was visiting from San Francisco and I had invited him along to the party. Sadly he mistook the Soft Machine for an audience jam session and may have even left before the Pink Floyd came on. He was terrified by the whole event and wrote an unintentionally funny report in his column in the San Francisco Examiner:

“The bands didn’t show, so there was a large pickup band of assorted instruments on a small central platform. Sometimes they were making rhythmic sounds, sometimes not. The place is literally an old roundhouse, with the doors for the locomotives all boarded up and the tracks and turntable gone, but still with a dirt floor (or was it just very dirty?). The only lights were three spotlights. The single entrance and exit was through a little wooden door about three feet wide, up a narrow wooden stair, turning two corners, and along an aisle about two and a half feet wide made by nailing down a long table.

“Eventually about 3,500 people crowded past this series of inflammable obstacles. I felt exactly like I was on the Titanic. Far be it for me to holler copper, but I was dumbfounded that the police and fire authorities permitted even a dozen people to congregate in such a trap. Mary and I left as early as we politely could.”

Psychedelic debutante, Susie Gawler-Wright on the cover of International Times # 11, 1967.

Hunter Davies in the Sunday Times reviewed the event with less concern for his own safety, providing the first national press for the Pink Floyd:

“At the launching of the new magazine IT the other night a pop group called the Pink Floyd played throbbing music while a series of bizarre coloured shapes flashed on a huge screen behind them. Someone had made a mountain of jelly and another person had parked his motor-bike in the middle of the room. All apparently very psychedelic …

“The group’s bass guitarist, Roger Waters, [said] ‘It’s totally anarchistic. But it’s co-operative anarchy if you see what I mean. It’s definitely a complete realisation of the aims of psychedelia. But if you take LSD what you experience depends entirely on who you are. Our music may give you the screaming horrors or throw you into screaming ecstasy. Mostly it’s the latter. We find our audiences stop dancing now. We tend to get them standing there totally grooved with their mouths open.’ Hmmm.”

The event has been described as the first ever ‘rave’. It was a lot of fun and it launched IT on the London scene.

* The claim that Syd was the first guitarist to use this is nonsense. Binson had been making them since the late Fifties.

* Syd and his circle had already experimented with magic mushrooms – an experience documented on an 8-mm colour film shot by Nigel Gordon in the Gog Magog hills outside Cambridge. The footage has been widely bootlegged on video and DVD under the erroneous title Syd’s First Trip.

* Colour television was introduced to Britain via BBC-2 in the summer of 1967.

* As the paper had been raided on obscenity grounds by this time, her pubic hair was censored by more psychedelic squiggles to avoid another bust.