IT almost immediately ran out of money and Hoppy decided to use the same formula that had provided funds for the London Free School to provide funds. The biggest challenge for IT was paying the staff wages so when he and Joe Boyd decided to start an underground club in the West End, it was agreed that the staff of IT would run it and be paid a high enough wage to make up for IT’s shortcomings. UFO Limited was a private company owned by Joe and Hoppy but it was generous in its support of the underground.

The UFO club – pronounced You-Fow – was the making of the Pink Floyd; this was where they were filmed by foreign crews, it was where journalists were invited to see them, and it was home to the greatest concentration of their fans, even though they played there only a handful of times. They were more or less unknown when UFO started, but were famous when it closed, less than a year later. At first Hoppy and Joe decided to try two gigs, one each side of Christmas, and if they were a success, to continue the event on a weekly basis. The Pink Floyd played at both events. UFO immediately became the in club of the London underground scene and the Pink Floyd its resident house band.

UFO was held every Friday night, all night, in the Blarney Club, an Irish Ballroom in a basement at 31 Tottenham Court Road featuring a distinctly Hibernian décor. The rent was only £15 for the night but because of the cinemas on the ground floor, no music was permitted until after 10pm. A wide, rather grand staircase led down to the ballroom to the left at the bottom, from which stray blobs of psychedelic light appeared to be escaping, as if oozing from the room. Halfway down the stairs, Mickey Farren, his hair a magnificent Afro, controlled the admission. As the club became very hot, the stairs were usually filled with people sitting on the steps, getting some air. It was a traditional ballroom, complete with a revolving mirror ball suspended from the ceiling – which the light show operators incorporated into their projections – and a polished dance floor. The only serious argument that the owner Mr. Gannon had with the organisers was when filmmaker Jack Henry Moore wanted to pile sand on the floor as part of an environmental happening. Apparently in the old days of cutthroat competition between ballroom owners, one of the ways of sabotaging a rival was to put sand on his dance floor.

Joe Boyd: “The object of the club is to provide a place for experimental pop music and also for the mixing of medias, light shows and theatrical happenings. We also show New York avant-garde films. There is a very laissez faire attitude at the club. There is no attempt made to make people fit into a formula, and this attracts the further out kids of London. If they want to lie on the floor they can, or if they want to jump on the stage they can, as long as they don’t interfere with the group of course.”

In addition to the bands, there was always a feature film – often a Marilyn Monroe classic or Charlie Chaplin – and other, more experimental films screened by the London Filmmakers Co-op such as films by Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol from the New York Cinematheque or Antony Balch and William Burroughs’ Towers Open Fire. UFO was known for its light shows which were not only directed at the band, but at all the walls and ceiling to provide a total environment. Sometimes the films were used as a part of multi-media events, such as the time when a modern jazz combo improvised to old black and white Pathé newsreels.

Nick Mason: “It seems pretty strange, looking back on it – really hard to describe. Endless rock groups, that’s what ‘underground’ meant to the people, but that wasn’t what it really was. It was a mixture of bands, poets, jugglers and all sorts of acts.”

Playwright David Z. Mairowitz, then working for IT, put on a weekly experimental drama, like an underground soap opera, called ‘The Flight Of The Erogenous’ which seemed to involve a lot of foam and paint being thrown about and female clothing being removed. It always attracted a decent crowd. One week someone inflated a silver weather balloon, and that bounced around the room for a while before being squeezed through the double doors and up the stairs (inspiration for the Floyd’s future flying pigs?) The Giant Sun Trolley experimental sound/jazz group was a pickup band created by the audience; it became Hydrogen Jukebox – named after the Allen Ginsberg poem – and eventually the Third Ear Band.

Nick Mason told Zigzag: ‘It [UFO] gets rosier with age, but there is a germ of truth in it, because for a brief moment there looked as if there might actually be some combining of activities. People would go down to this place and a number of people would do a number of things, rather than simply one band performing. There would be some mad actors, a couple of light shows, perhaps the recitation of some poetry or verse, and a lot of wandering about and a lot of cheerful chatter going on.” In the early days, the Pink Floyd mingled with the crowd since it was more interesting than sitting backstage.

Roger Waters in full psychedelic mode.

There was a food concession run by Greg Sams from the Praed Street macrobiotic restaurant and he did good business at three in the morning when everyone had the munchies. Greg also used the long nighttime hours to explain the ideas behind macrobiotics to his customers. Acid and pot was easily obtainable from any number of dealers including the large German dealer Manfred, who apparently always gave away his first 400 trips. Tony Smythe from the Council for Civil Liberties was always on hand, usually conducting meetings in a back room, in case the police decided to raid and of course Michael X used it as a place to relive white liberals of guilt money by getting people to contribute to his – largely fictitious – projects in the Black Community. International Times was on sale and other underground publications. The Kings Road clothes shops Granny Takes A Trip, Hung On You and Dandy Fashions, were always represented in case anyone fancied ordering a frilly shirt or a pair of yellow crushed velvet loon pants.

The UFO audience arrived in their psychedelic finery: shimmering silver micro-mini-skirts contrasted with full length granny dresses in silk or chiffon; revamped negligees worn as tops, velvet jackets, shirts with huge lapels and frilly fronts in tasteful paisley or Liberty flower pattern prints. The local police never really got the hang of the new Sixties clothes and hairstyles. One time they spotted someone entering the club whose description matched that of a 16-year old runaway girl. Half way to Tottenham Court Road police station, a block away, they discovered they had seized a young man. In the early days they were friendly, and one telephone call from them ran as follows:

“We’ve got one of yours ‘ere. Wot shall we do wiv ‘im?”

Mickey Farren, having seen an acid crazed hippie, eyes ablaze, refractive lens in the middle of his forehead, flash past him up the stairs and heading in the direction of the police station: “Just hang onto ‘im. We’ll send someone up to get ‘im.”

There was dancing at the UFO, but usually to records: ‘Granny Takes A Trip’ by the Purple Gang and ‘My White Bicycle’ by Tomorrow, became perennial favourites and when a band was on, most people sat and listened. There were loon dancers near the front, but most of the audience sat on the floor, which, according to Robert Wyatt, was very conducive to good playing:

“One of the biggest influences was the atmosphere at UFO. In keeping with the general ersatz orientalism of the social setup you’d have an audience sitting down … Just the atmosphere created by an audience sitting down was very inductive to playing, as in Indian classical music, a long droning introduction to a tune. It’s quite impossible if you’ve got a room full of beer swigging people standing up waiting for action, it’s very hard starting with a drone. But if you’ve got a floor full of people, even the few that are listening, they’re quite happy to wait for a half hour for the first tune to get off the ground.”

UFO Club posters by Michael English and Nigel Waymouth.

Long improvisations were needed in long sets and were easier if you were playing experimental or freeform music; when the Beatles were on stage for eight hours a night in Hamburg, they developed a 30 minute version of Ray Charles’ ‘What’d I Say?’ to fill the time. As far as the Soft Machine were concerned it was a practical response to the stage situation: Mike Ratledge’s Lowry Holiday Deluxe organ had a tendency to feedback during pauses if the volume was very high – as it always was at UFO – which prompted a style of continuous playing since they couldn’t stop.

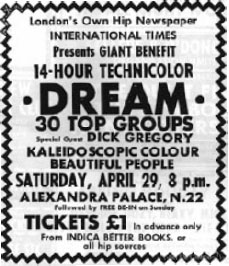

Announcements at UFO were usually more along the lines of the page headings in International Times intoned by Jack Henry Moore in his campy Southern accent: “If you can’t turn your parents on, turn on them” or “Maybe tonight is kissing night. Don’t just kiss your lover tonight, kiss your friends”. Richard Neville called UFO “traumatic, familial, euphoric” and described it as “the Underground’s living equivalent to The Times letters column.” Whenever anything happened that affected the scene, everyone gathered at UFO to discuss it: when the police busted International Times, it was at UFO that the latest issue was read aloud from the manuscripts which had been quickly hidden in Indica Bookshop on the ground floor; when Hoppy was jailed for a small amount of pot, all manner of incendiary responses to his incarceration were proposed at that week’s UFO; and when Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were sentenced to prison after the News of the World set them up for a police bust, it was from UFO that people set off to hold a midnight demonstration outside that newspaper’s Fleet Street headquarters; probably the first night-time demonstration Britain had ever known.

In addition to the Pink Floyd, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and the Soft Machine were also regarded as house bands at UFO. Arthur Brown was tall and lanky and pre-figured Kiss by painting his face into a crazy mask for each performance. He always entered wearing a flaming head-dress which more than once had to be put out with a pint of beer emptied over his head when his cloak caught fire as he dipped and dived; he was an energetic dancer and really knew how to get the audience going. (The beer came from backstage; there was no alcohol sold at UFO). Pete Townshend, who was a regular at UFO, recognised his talent and got him signed to Track, the Who’s new label.*

For a while it seemed that the Soft Machine were the Grateful Dead to the Pink Floyd’s Jefferson Airplane (or vice versa); these two underground groups came from similar middle class backgrounds – Canterbury and Cambridge – and played to the same underground audience. They shared the bill at the launch party of International Times, and if the Floyd were in on the origins of UFO, members of the Soft Machine were involved with the people who created International Times from as far back as 1964. Nonetheless, it was only Daevid Allen who really fitted in.

Robert Wyatt: “We felt like suburban fakes dressed up on Saturday and visiting the city. I never dared take LSD. I was in total awe of the audience at UFO, people like the Oz crowd. We used to come in on the train and pretend we were like them. Just because we played long solos people assumed we were stoned, which was great for our credibility. I didn’t know much about it. Daevid had connections with a whole generation of people there, all these people with very advanced ideas. Daevid was the internationalist of the group, he got us into all of that. The rest of us were all provincial.”

Daevid’s connections went right back to the Beat Hotel in Paris, when he took over Allen Ginsberg’s room in 1958 after the poet returned to New York. Daevid, known as a poet back then, knew many of the early experimenters with LSD, having first taken it in 1960 so it was almost inevitable that his band – named after one of William Burroughs’ books – should become a UFO regular. It was a short lived season because in August 1967 British customs refused to let Daevid back into the country after a French tour on the grounds that he had overstayed his visa the last time he entered. Soft Machine was reduced to a trio and Daevid went to Paris and started Gong.

At the time Soft Machine had the best light show in Britain as Daevid explained in his book Gong Dreaming: “The light show we used for our UFO gigs was run by Mark Boyle, a Scottish sculptor turned liquid lightshow alchemist. The combinations of liquids he sandwiched between the twin glass lenses, that began to alter as they were heated by the projector lamp, were his professional secret. He worked inside a tent so nobody could see what he was doing. Some said he used his own fresh sperm mixed with the colours and other liquids and fluids. He felt a special affinity for our music and although it could not be logically programmed, his lights synchronised with our stops, starts, peaks, and lows, as if it had all been pre-organised by a wizardly Atlantean reincarnate.”

Mark Boyle had evolved his early light show at Mike Leonard’s Sound/Light workshop at Hornsey Art College, the same place that Joey Gannon’s ideas were developed. Boyle operated the stage lights and sometimes played tricks on the bands, like making green bubbles emerge from their tightly stretched flies – a trick he liked to play on Roger Waters – but he was only one of many lightshow operators and the Floyd usually had their own spectacular show. The blobs and bubbles of the lights were absorbed into each other or divided like the school diagrams of amoebas. One’s whole vision was filled with pulsating cellular forms, like being inside a plant or your own body, the sap rushing, being borne along by the relentless rhythm. People sometimes just stood open mouthed.

UFO had a number of different light shows in simultaneous operation including one by Jack Braclin’s Fireacre Lights that had played at the London Free School. Fiveacres was his psychedelic nudist colony near Watford, which consisted mostly of local teachers living in caravans. The wooden clubhouse had a ‘trip machine’ consisting of an electrically powered wheel on the ceiling from which strips of silver Mellonex hung down to the floor. As the wheel slowly turned, the assembled tripping nudists watched the flashing colours to the accompaniment of a very scratched copy of Zappa’s Freak Out. The Pink Floyd played there on November 5, 1966, Guy Fawkes Night – stopping off to see the fireworks on their way back to London from a concert at Wilton Hall, Bletchley.

At UFO Jack sometimes projected on to the bands, as he had done at the LFS, but mostly kept one end of the large room fully filled with moving blobs and white dots. Jack’s lights were some of the best in town, and he soon set up his own weekly nightclub called Happening 44, at 44 Gerrard Street in Soho which on other nights was a seedy strip club. Jack had first developed his light shows for patients at mental hospitals where the patients would first listen to some records and be given a cup of coffee. This was followed by an hour of slide projections.

According to Alph Moorcroft the best of these was made by a girl patient at Knapsbury mental hospital: “The slides consisted of bright heaving masses of colour and produced amazing emotional reactions, tears and often a state of disturbance which lasted for days. Because of these reactions some of the hospitals he visited decided that his shows were ‘too loaded’ emotionally and therefore stopped them.” The effect at UFO was sometimes equally hypnotic and people danced for hours surrounded by the swirling shapes and points of light.

A wide variety of bands performed at UFO: Procol Harum played their second ever gig there and their fourth (by which time they were already at number one with ‘A Whiter Shade Of Pale’); the Move made an attempt at underground credibility by playing but the UFO audience didn’t like their mohair suits and aggressive act and booed them. The rest of the country, however, seemed convinced by their nods to flower power such as ‘I Can Hear The Grass Grow’ and ‘Flowers In The Rain.’ The latter was the first single to be played on BBC’s new Radio 1 pop channel but the publicity campaign, consisting of a postcard involving a drawing of the prime minister Harold Wilson naked in the bath assisted by his secretary, attracted a winning libel suit and they group forfeited their royalties from this, one of their biggest hits. Jimi Hendrix, whose manager, Chas Chandler now also managed the Soft Machine, used to come down in the early hours and jam with whoever was on stage. Sadly these were never recorded but to those of us who witnessed them, they are among the high spots of the Sixties.

‘Yeah, sometimes, we just sorta let loose a bit and started hitting the guitar a bit harder and not worrying quite so much about the chords.’

Syd Barrett

More than anything else, the UFO club remains synonymous with the Pink Floyd’s rise to fame. By now Syd had permed his hair into a Hendrix Afro – as did Eric Clapton and many other musicians – and was dressed in silks and satins and flowing scarves from Thea Porter, Granny Takes A Trip and Hung On You. Roger Waters and the others always looked vaguely uncomfortable in hippie clothing, particularly when Roger appeared with what looked like a pelmet sewn to the bottom of his trouser legs. The idea of Roger perming his hair was unthinkable, but Syd not only looked the part but was himself a sartorial inspiration to the next generation: people like Marc Bolan modelled themselves on Syd and his Vidal Sassoon perm.

When the Floyd took the stage, and began the familiar descending cadence of bass notes that led to ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ the hippies sitting out on the stairs would rush the doors to get in and the crowd on the dance floor would push forward. The group talked about the dancing in an early interview for Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Canadian scriptwriter and film-maker Nancy Bacal, who studied at the Royal Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (RADA) was producing radio shows for CBC. At that time she was living with Michael de Freitas (Michael X) who soon introduced her to the London Free School scene. In January 1967 she made a programme about the newly emergent London underground scene for CBC and interviewed Nick Mason, Roger Waters and Syd Barrett. In doing so, Bacal inadvertently taped one of the very few surviving recordings of Barrett talking about his music and the band.

Nancy Bacal: “In a frenetic haze of sound and sight, a new concept of music has begun to penetrate the senses of Britain’s already hopped-up beat fans. Some call it free sound, others prefer to include it in the psychedelic wave of ‘isms’ already circulating around the Western hemisphere. But this music, here and now, is that of the Pink Floyd, a group of four young musicians, a light man, and an array of equipment sadistically designed to shatter the strongest nerves.”

At first Nick demurred, telling her: “We didn’t start out trying to get anything new … We originally started virtually as an R&B group.”

Syd: “Yeah, sometimes, we just sorta let loose a bit and started hitting the guitar a bit harder and not worrying quite so much about the chords.”

Roger: “It stopped being third rate academic rock, y’know? It started being a sort of intuitive groove, really.”

Nick: “It’s free-form. In terms of construction it’s almost like jazz, where you start off with a riff and then you improvise on this except …”

Roger: “Where it differs from jazz is that if you’re improvising around a jazz number, if it’s a 16 bar number you stick to 16 bar choruses and you take 16 bar solos, whereas with us it starts and we may play three choruses of something that lasts for 17 and a half bars each chorus and then it’ll stop happening and it’ll stop happening when it stops happening and it may be 423 bars later or four.”

Syd: “And it’s not like jazz music ‘cause …”

Nick: “We all want to be pop stars – we don’t want to be jazz musicians.”

Syd: “Exactly. And I mean we play for people to dance to – they don’t seem to dance much now but that was the initial idea. So we play loudly and we’re playing with electric guitars, so we’re utilising all the volume and all the effects you can get. But now in fact we’re trying to develop this by using the lights.”

Roger: “But the thing about the jazz thing is that we don’t have this great musician thing. Y’know, we don’t really look upon ourselves as musicians as such, y’know, period … reading the dots, all that stuff.”

Nancy asked how important the visual aspect of the production was and they all agreed it was very important …

Syd: “It’s quite a revelation to have people operating something like lights while you’re playing as a direct stimulus to what you’re playing. It’s rather like audience reaction except it’s sort of on a higher level, you know, you can respond to it and then the lights will respond back …”

5th Dimension, Leicester; UFO Club and Saville Theatre posters by Michael English and Nigel Waymouth.

During the early UFO period, the band was Syd’s: he was the lead singer, lead guitarist and group songwriter. Just as later his illness meant that he was no longer wholly present, in the early days he was 100% there, totally involved, giving everything to the music. As the lead singer he was the only one to attract attention from the audience; because the band was obscured by the light show the Pink Floyd were never famous in the usual rock star sense and even at the height of their fame they were able to walk the streets and go to shops without anyone knowing who they were. Syd, however, enjoyed fame and made sure that the girls up front could see him in his Hendrix afro and his Kings Road psychedelic finery.

The nature of Syd’s songs – often in the first person – also demanded that the audience knew who was singing them. Syd’s lyrics were very much of the Zeitgeist: Keith West, the Incredible String Band, Fairport Convention, the Kinks and many other bands including the Beatles were singing about English subject matter in an English accent instead of the imitation American accents and pseudo-American themes that had previously dominated the charts. Barrett’s songs were those of a clever middle class schoolboy. If Mary Tourtel’s cartoon creation Rupert Bear took acid and wrote rock songs they would be like Syd Barrett’s efforts: lines and images from Hilaire Belloc whom Syd adored, particularly from his nonsense verse; names and images from Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings; from Edward Lear; from Kenneth Grahame’s Wind In The Willows; Lewis Carroll’s Alice books; folk tales of the Cambridgeshire fens; bits of Shakespeare; bits from Christopher Smart’s ‘Jubilate’ (his ‘My Cat Geoffrey’ also influenced Allen Ginsberg); a collage of whatever was in the papers, overheard conversation, friend’s names, everyday life. His girlfriends also inspired lines in his Floyd songs; Jenny Spires appeared as “Jennifer Gentle, she’s a witch” in ‘Lucifer Sam’, Lynsey Korner was described as “Cornering neatly, she trips up sweetly” in ‘Apples And Oranges’. Anything and everything went in.

The songs caught the spirit of the time, they had an innocence, a sweetness, a poignancy, and an evocation of childhood that was very appealing. Syd’s lyrics connected directly to shared British memories of fairytales, of Hobbits, of going down the rabbit hole, Rupert Bear being called home for tea by his mother standing at the gate; unflappable Professor Quatermass seemingly unperturbed that one of his astronauts has been somehow absorbed by the other in a cheap soundstage made from a garden shed; square-jawed Dan Dare confronting the aliens each week in the Eagle; Flash Gordon bumping around a cheap interplanetary set in a rocketship that burned like a damp firework in search of aliens with angel wings; Syd and Rick’s bleeps and squeals like the scary BBC Radiophonic Workshop soundtrack to the Red Planet radio serial; the boy at school with a scared mouse in his pocket; Uncle Mac and BBC Childrens’ Hour; Christopher Robin; the excitement at first hearing rock ‘n’ roll washing in on waves of static from Luxembourg; it was all there.

Though they seem to have a string element of spontaneous, stream-of-consciousness rambling to them, Peter Jenner says that Syd drew his songs on paper like the overlapping circles of Venn diagrams, carefully planning the images and their relationship. All of this was in direct contrast to the music; though he was capable of well-crafted, pop melodies such as ‘Arnold Layne’ and ‘See Emily Play’, his musical interests lay in exploring the outer limits of sound production: feedback – then still a new thing – detuning and retuning the guitar strings during the performance, or by creating screeches, blips, insect clicks and metallic shrieks by running his Zippo lighter up and down the strings and manipulating his Binson Echorec, all in the best Keith Rowe manner. It was this aspect of Barrett’s playing that provides continuity within the complete oeuvre of the Pink Floyd; they did not jump straight from jolly pop songs to long meandering improvisations. In the beginning they had both and they sat in uneasy opposition to each other until the pop songs were jettisoned.

The extended improvisations were much appreciated at UFO and hardly liked at all in most other venues. Even at UFO it must be said that the Floyd could actually be pretty boring after a while because they were not accomplished musicians and though the loon dancers and Nick Mason’s drumming kept it going, Syd often ran out of ideas on long pieces as he fooled with his Binson Echorec and tried to come up with something new. Nick always reminded me of Chico Hamilton in Jazz On A Summer’s Day with his muted mallets, steadfastly keeping the number alive while Syd turned his knobs and fumbled with the machine head.

The poster for the first UFO/Nite Tripper club event, designed by Michael English and featuring model Karen Astley, Pete Townshend’s girlfriend.

Nick: “We could only play in London, because there the audience was more tolerant and was willing to withstand 10 minutes of shit to discover five minutes of good music. We were at an experimental stage. We set out for unbelievable solos where no one else would dare.”

Rick: “The band was an improvising group in the beginning. A lot of rubbish came out of it but a lot of good too. A lot of that was obviously to do with Syd – that was the way he worked. Then things got a lot more structured when Dave joined. He was a fine guitarist, but he wasn’t really comfortable with all that wild psychedelic stuff.”

Rick was the only really competent player: Nick did a good job on time keeping but rarely strayed from familiar time signatures. Syd had a fairly rudimentary knowledge of lead guitar, preferring the expedient of making abstract sounds with his instrument rather than astonishing the girls with tricky chords and difficult solos. Roger was never interested in expressing himself by becoming an adept instrumentalist – in fact Rick used to have to tune his bass for him because he was tone deaf.

Waters told the BBC: “There was a need to experiment in order to find another way of expressing ourselves that didn’t involve practicing playing guitar for 10 years. At that time people were standing there in little suits with Gibsons and bass guitars held against the chest … and although it wasn’t very complicated stuff it wasn’t something I was interested in doing. In fact if you turned the thing up loud and used a plectrum – and I had a Rickenbacker which I bought with a grant, in fact my entire terms grant – if you banged it hard it made strange noises and I found if you pushed the strings against the pick-ups, it made a funny clicking noise.”

It was at UFO that Jenny Fabian first saw the Pink Floyd whom she dubbed Satin Odyssey in her lightly fictionalised roman-a-clef Groupie. “They were the first group to open people up to sound and colour, and I took my first trip down there when the Satin were playing, and the experience took my mind right out and I don’t think it came back the same.’ She was going out with Andrew King, renamed Nigel Bishop in her book, but it was Syd, whom she calls Ben, she really desired.

“He was tall and thin, and his eyes had the polished look I’d seen in other people who had taken too many trips in too short a time. I found him completely removed from the other three in the group; he was very withdrawn and smiled a lot to himself.”

Inevitably she lured him into her bedroom and the breathless reader knows exactly what is going to happen when “Finally Ben reached down and untied his gymshoes …” As Syd later said, “Everything was so rosy at UFO. It was really nice to go there after slogging around the pubs and so on. Everyone had their own thing.”

The audience wore lace and crushed velvet and the women found antique granny dresses, see-through tops or mico-mini dresses printed in psychedelic patterns. There were kaftans and bells – DJ John Peel always looked faintly embarrassed by his kaftan – and bare feet which gave a distinct aroma to the room. Many of them seemed very young and vulnerable and the staff felt very protective toward them; one of the rooms backstage was used to talk people down from bad trips. There was a man with long hair and a thick afghan coat who stood on a chair to the left of the stage each week who appeared to be unaffected by the fact that the temperature was about 90 degrees, and another who always brought his skinny dog with him who objected violently when animal loving hippies suggested that the high volume and heat might be bad for the poor animal’s health.

Rock stars like Paul McCartney could come and sit in the dust and listen to the music like anyone else and not be bothered. Some, like Pete Townshend, were regulars and saw themselves as part of the scene. The girl with ‘UFO’ painted across her face by Michael English on the first UFO poster was Pete’s girlfriend and future wife Karen Astley. He remembered dancing on acid to the Pink Floyd:

“I remember being in the UFO club with my girlfriend, dancing under the influence of acid. My girlfriend used to go out with no knickers and no bra on, in a dress that looked like it had been made out of a cake wrapper, and I remember a bunch of mod boys, still doing leapers, going up to her, and literally touching her up while she was dancing and she didn’t know that they were doing it. I was just totally lost: she’s there going off into the world of Roger Waters and his impenetrable leer, and there’s my young lads coming down to see what’s happening: ‘Fuckin’ hell, there’s Pete Townshend, and he’s wearing a dress.’”

Though the audience usually sat for the Pink Floyd, there were a certain number who danced: one or two who were proficient in proper loon dancing braved the front of the stage, but most of them writhed about to the right of the stage. In her CBC interview Nancy Bacal asked the band if their audiences danced. “They may dance,” Nick told her. “It depends on the sort of music and what’s happening.”

Syd: “Yeah and anyway you hardly ever get the sort of dancing right from the beginning that you get just as a response to the rhythm. Usually people stand there and if they … [laughs] get into some sort of hysteria while they’re there …”

Nick: “… the dancing takes the form of a frenzy which is very good.”

Roger: “They don’t all stand in a line and do the Madison. The audiences tend to be standing there and just one or two people maybe will suddenly flip out and rush forward and start leaping up and down …”

Syd: “Freak out I think is the word, you’re looking for!”

Nick: “It’s an excellent thing because this is what dancing is …”

Syd: “This is really what dancing is!”

UFO was also a useful showcase for the Pink Floyd so that music business people could catch their act.

John Peel: “The first time I ever saw them was at the old UFO club in Tottenham Court Road, where all of the hippies used to put on Kaftans and bells and beads and go and lie on the floor in an altered condition and listen to whatever was going on.” The Floyd’s appearances on Peel’s influential Top Gear show were very important to their career.

Perhaps another reason why the UFO has become so legendary is because it produced the only English equivalent of the American Family Dog and Bill Graham posters. Most were done by Michael English and Nigel Waymouth, operating under the name of Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, a derivative of the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut who organised the legendary journey to Punt, only changed to incorporate the word ‘hash’. These were published by the equally faux Egyptian Osiris Visions Limited poster company owned by Joe Boyd, which quickly branched out and began making posters for other venues such as Brian Epstein’s Saville Theatre, for record companies, art galleries and boutiques. The posters were silk-screened by hand, and often incorporated exquisite rainbow effects, running from silver to gold, or orange to yellow.*

Unfortunately, UFO articles in the Sunday Times and Financial Times, as well as the music weeklies, attracted the attention of the gutter press and The People sent an undercover reporter down to sniff out some dirt. Their man reported observing someone smoking a joss-stick – whatever that means – and even saw a couple kissing. Though the article was mild by Fleet Street’s muck-raking standards it was enough to alert the police. The uneasy truce that had existed between Tottenham Court Road police station and the UFO management came to an end. The police used their usual tactics and threatened to rescind the Blarney Club’s drinks licence, even though no alcohol was served at UFO. Mr. Gannon had no choice but to ask UFO to leave, but not before he revealed that he had been offered quite a large sum of money by one of the Fleet Street Sundays to spill the beans on the hippies. Brian Epstein offered the use of the Saville Theatre, but Joe Boyd and Hoppy decided that the Roundhouse, where it had all started, was a more appropriate venue.

Centre 42 had been astonished when IT used the Roundhouse for a party and realised that they had been missing out on a way of raising funds; they brought the place up to fire and health regulation standards and began renting it as a venue. By the time UFO moved there the Roundhouse was now in much better condition, with toilets and a proper entrance. In fact, even before UFO began, the Pink Floyd had returned to the Roundhouse for something called ‘Psychodelphia Versus Ian Smith. Giant Freak Out’ on December 3, where the audience was encouraged to “bring your own happenings and ecstatogenic substances.” The Ian Smith in question was the pro-apartheid right-winger who had declared independence from British rule for Rhodesia and who was depicted on the poster for the event – which was organised by the Majority Rule for Rhodesia Committee – with his face annotated to look like that of Hitler with the moustache and cowlick.

Naturally this interested the Daily Telegraph who demanded to know what “ecstatogenic substances” were. Organiser Roland Muldoon told them they were “Anything which produces ecstasy in the body. Alcohol was not allowed for the rave-up, unhappily, and nor were drugs … All it means really is that you should bring your own bird.”

Fleet Street never fully understood what the Sixties were all about.