When Roger and Syd went to study in London, David Gilmour remained in Cambridge and started Jokers Wild. In 1966, when the band seemed to have reached a dead end David, together with fellow Cambridge musicians drummer Willie Wilson and bassist Ricky Wills took up the offer of a gig in a Marbella night club. When that job finished they moved on to Paris. At first they called themselves Bullitt.

David: “I can’t remember why we called it that. I was living with my band in France and we just thought of a name, but as we approached the Summer of Love it just didn’t seem to be appropriate!” Consequently in Paris they became Flowers, because their manager thought they needed a name more in keeping with the times. Flowers got a regular weekend residency at Le Bilboquet, the famous Left Bank nightclub at 13 rue Benoit, a home to Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Kenny Clarke, Duke Ellington, Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton and Charlie Parker in the great days of Paris jazz.

David: “We struggled to get by, living this nomadic existence in France on 50 francs a night each – three or four quid back then, and that only a couple of times a week.” The trio lived in a succession of cheap Left Bank hotels, staying two to a room and often had to spend all night in a Paris bar, nursing one glass of beer, because they had nowhere to stay and no money. David stayed in Paris for a year.

He kept up with old friends in the Pink Floyd, visiting them in the studio in May 1967 when they were recording ‘See Emily Play’ and then, in August, he heard The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn LP. He told Phil Sutcliffe: “It sounded terrific and I was sick with jealousy. I’d been ill. Malnutrition, strangely enough, the hospital gave me sugar to suck on.” Gilmour and his cohorts in Flowers paid their hotel bill on the weekends, after being paid by Le Bilboquet, but that only left enough money to buy food for a few days, and then they would run out and sometimes had to go without. “Extreme pigheadedness and stubbornness can be both great qualities and character faults,” he said. “I hung on too long in France, but in September ‘67 I thought, ‘I’ve had enough. I’m going home’.”

The three of them went to one or two people who owed them money and threatened them with violence if they didn’t pay up. At one booking agency they took equipment from the office that they thought they could sell after the agent made the usual excuses. On the way to Calais they ran out of money for petrol for their battered old Ford Thames van. They stopped at a building site and siphoned diesel into their tank. Willie Wilson warned that although the van would run on this mixture of diesel and petrol, it would not start again, so when they reached Calais at 3am, they kept the engine running all night as they waited for the first ferry of the day. Once on board they were made to switch off the motor and sure enough, at Dover they had to push the van off the ferry onto the dock. David: “I felt a bit defeated at that point.” He told Ricky and Willie that he wasn’t going back to Cambridge – “That would have been one defeatist stage too far” – he would stay in London and try and make it in the music business.

David took a job as a van driver for Ossie Clarke and Alice ‘No Pants’ Pollock’s Kings Road dress shop Quorum and spent his evenings hanging around the clubs and getting to know the music scene, hoping to put together a new group. Then, on December 6, at a Floyd gig at the Royal College of Art, he was sounded out about joining the Floyd.

David: “Nick actually came to me and sort of said ‘Nudge, nudge … if such and such happened, and if this, and if that, would you be interested in it?’ and went through that whole thing in a fairly roundabout way, suggesting that this might come off at some point. And then just after Christmas, right after their Olympia gig, I actually got a phone call … where I was staying. I didn’t actually have a phone, or they didn’t know it, but they sent a message through someone else that they knew that knew me, for me to get in touch for taking the job, so to speak. There was no real discussion, or any meetings to think about it or any auditions or anything like that. They just said, ‘Did I want to?’ and I said ‘Yes’, and it was as simple as that.”

Rick Wright told Q magazine: “When Syd left Pink Floyd we actually asked Jeff Beck to join, he was our first choice. He was doing OK at the time so he turned us down.” Beck would have been a more commercial but unlikely choice, since he was already well-known and would have immediately upped their profile and fees, but David Gilmour was in fact the best possible candidate they could have found.

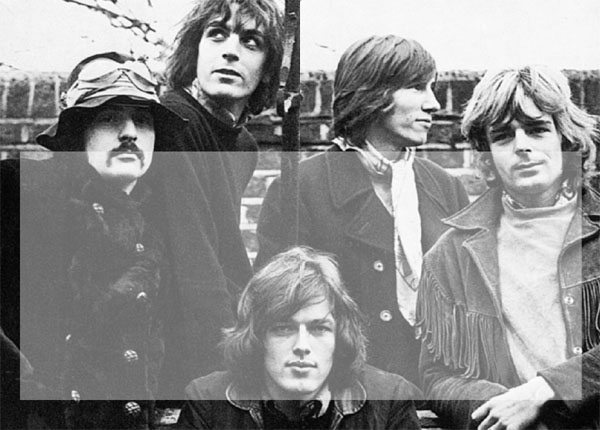

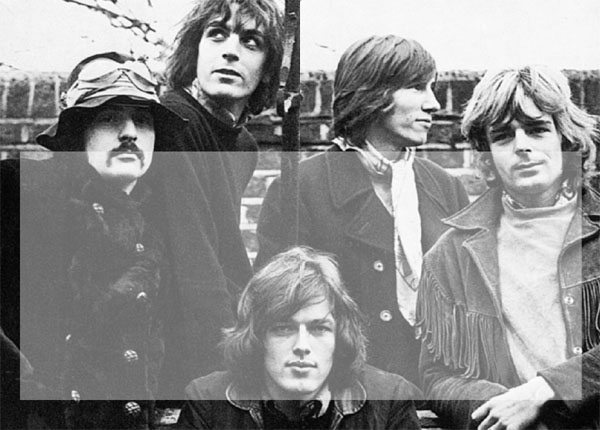

The brief five-man line up of Pink Floyd, early 1968. Syd fades from view.

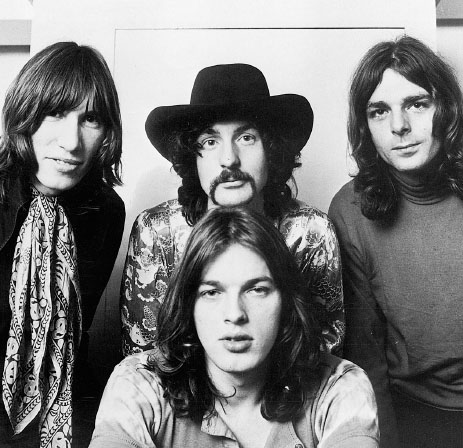

Pink Floyd Mark II, 1968. L-R: David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Roger Waters, Rick Wright.

David: “They just basically asked me because I was probably the only other person they really knew fairly well that could sing and play guitar, and came from a reasonably similar background, so that we knew that we’d probably get on reasonably well and could communicate, and they know what I could do – I mean I think the other person they had in mind was Jeff Beck, which would have been slightly different.”

Nick: “During a month, the five of us rehearsed together. Our idea was to adopt the Beach Boys’ formula, in which Brian Wilson got together with the band on stage when he wanted to. We absolutely wanted to preserve Syd in Pink Floyd one way or the other. But he let himself be influenced by some people, who kept repeating he was the only talent in the band and should pursue a solo career.”

This referred of course to Peter Jenner and Andrew King who still thought that Syd was the only creative mind in the band and that the Pink Floyd would go nowhere without him. In fact, in the long term Syd might well have held them back with his love of pop star glamour but we will never know. By now Syd was virtually impossible to communicate with, they had no way of knowing what he was thinking or what he wanted. He was an old friend and they found themselves in an almost impossible dilemma.

Roger: “Syd turned into a very strange person. Whether he was sick in any way or not is not for us to say in these days of dispute about the nature of madness. All I know is that he was fucking murder to live and work with.”

Initially the band saw themselves as having three options: the five piece where Syd could join them onstage if he felt like it; Syd not playing with them but staying home and writing for them, thus remaining part of the group, and a third where Syd left the group and was replaced by David. It only took a handful of gigs to show that they could no longer allow Syd to appear onstage with them: he fixed the audience with a glassy stare, and if he touched his guitar at all, it was to detune the strings and strum rattling discords. Sometimes the strings would fall off altogether. As they were not a free-form experimental group, this did not enhance either their playing or their reputation.

It was difficult for Syd as well; at the band meeting where the idea of David joining the line-up had been proposed it had been made very clear to Syd that no disagreement was allowed. Technically David was the second guitarist and backup vocalist but as far as Syd was concerned, his old friend was, as Nick Mason put it, “an interloper”. Syd went through the motions of playing, as if he refused to get involved in this absurd charade, but as he contributed less and less, the need for his replacement became more and more clear.

This was the time of Syd’s brilliant comment on the band and his situation within it. At the school hall rehearsal room they used in north London, Syd attempted to teach the group a new song called ‘Have You Got It Yet?’ Each time they reached the chorus, Syd changed the arrangement. When he sang, ‘Have you got it yet?’ they all chorused back, ‘No, no.’ It lasted for an hour, before they realised that Syd was simply making them look foolish.

Nick: “So we were teaching Dave the numbers with the idea that we were going to be a five piece. But Syd came in with some new material. The song went ‘Have you got it yet?’ and he kept changing it so no-one could learn it.”

Roger: “It was a real act of mad genius. The interesting thing about it was that I didn’t suss it out at all. I stood there for about an hour while he was singing “Have you got it yet?” trying to explain that he was changing it all the time so I couldn’t follow it. He’d sing, ‘Have you got it yet?’ and I’d sing ‘No, no!’ Terrific!”

The others had all seen David in his various groups so there had been no need for him to play for them, but in order for him to become part of their recording contract he had to do an audition at EMI Studios. This he passed easily, first of all playing in the Hendrix mould, before showing how he could both sing and play like Syd; not a direct imitation, but in the same style. This was not surprising since he and Syd grew up together musically and he knew every aspect of Syd’s playing inside out. The Pink Floyd’s contract with EMI was formally revised to include David on March 18, 1968.

David had seen two or three of the Floyd’s gigs before being asked to join and had been shocked at how poor they sounded. It was obvious that the band could not carry on as it was; they were static, just marking time. David joining the band coincided, of course, with Roger taking over Syd’s role as leader of the group. David, as the new boy, and the youngest member by that crucial two years, came in for a lot of criticism from Waters.

David: “Roger assumed leadership of Pink Floyd because he was leadership material. He was bossy and pushy, and I’m very grateful that he was there to take the reins. But I felt like a new boy. And Roger, the jolly old soul that he was, rubbed it in to me: both the younger bit and the new-boy bit.” So much so, in fact, that after his first few days David left the band because Roger was making his life so difficult; fortunately a reconciliation was effected.

The five man Pink Floyd line-up was short-lived: they played the University of Aston in Birmingham, the Saturday Dance Date at the Winter Gardens Pavilion in Weston-super-Mare, two evening shows at Lewis Town Hall and a gig on the pier at Hastings. The end of Syd’s live career with the Pink Floyd came about on January 26, 1968 when the band set off to play the University of Southampton as support to Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Incredible String Band. As their white Bentley headed down Ladbroke Grove from a business meeting to pick him up, someone asked, ‘Shall we go and pick up Syd?’ and someone – generally thought to have been Roger – replied, ‘Oh, let’s not!’ and off they went to Southampton without him. The five-piece had lasted for only four gigs. This left David with the unenviable task of performing as lead vocalist and lead guitarist.

The band never told Gilmour to ‘Play like Syd Barrett’; if that was what they were looking for they would never have considered Jeff Beck for the position. It so happened that there were many similarities in style between Syd and David’s playing and, as they were still playing Syd’s material, and as David was a great mimic, he opted to play in a manner similar to Barrett until the group had developed some fresh, non-Syd, material: ‘I had to fit in with his style to an extent because his songs were so rigidly structured around it.’

Gilmour told Nicky Horne: ‘The first six months that I was in the band I really didn’t feel confident enough to actually start playing myself – I sat there mostly playing just rhythm guitar and I suppose, to be honest, at the time trying to sound a bit like Syd. But that didn’t last very long – I mean, it was obvious the group had to change into something completely different and they hadn’t asked me to join to sound exactly like Syd, but I mean – the numbers they were doing were still Syd’s numbers mostly. Consequently there’s that kind of a fixed thing in your head of how they have been played previously, and that kind of, makes it very much harder for you to strike out on your own and do it exactly how you would do it … and you haven’t got a clue how you would do it really because there’s already an imprinted thing in your brain of how the guitar is played on those things. Consequently it did take some time before I started getting into actually being a member of the band and feeling free to impose my own … guitar-playing style on it.

Accusations from Barrett fans that David was somehow an impostor who was imitating Syd’s style naturally angered him: “The facts of the matter are that I was using an echo box years before Syd was. I also used slide. I also taught Syd quite a lot about guitar. I mean, people saying that I pinched his style, when our backgrounds are so similar … yet we spent a lot of times as teenagers listening to the same music. Our influences are pretty much the same – and I was a couple of streets ahead of him at the time and was teaching him to play Stones’ riffs every lunchtime for a year at technical college. That kind of thing’s bound to get my back up – especially if you don’t check it.”

Syd, for his part, was confused and angry. He had never seen the others as merely his backing group, or himself as the leader of the band; he was devoted to the band and couldn’t really understand why he was no longer in it. When asked about his leaving by Mick Watts, he said: “It wasn’t really a war. I suppose it was really just a matter of being a little offhand about things. We didn’t feel there was one thing which was gonna make the decision at the minute. I mean, we did split up, and there was a lot of trouble. I don’t think the Pink Floyd had any trouble, but I had an awful scene, probably self-inflicted.’

Meanwhile, the rest of the band breathed a sigh of relief.

Nick: “After Syd, Dave was the difference between light and dark. He was absolutely into form and shape and he introduced that into the wilder numbers we’d created. We became far less difficult to enjoy.”

Rick agreed: “[Dave] was much more of a straight blues guitarist than Syd, of course, and very good. That changed the direction, although he did try to reproduce Syd’s style live.”

The first order of business was to complete the second Pink Floyd album; something which had become impossible in the final months of 1967 because of Syd’s unpredictable behaviour. They already had a few tracks in hand from a two day recording session at De Lane Lea studios in Kingsway on October 9-12, 1967 when they recorded Rick’s ‘Remember A Day’ with a nice slide solo by Syd, and Barrett’s extraordinary ‘Jugband Blues’* and ‘Vegetable Man’ – the latter written in the studio when Syd sat in the corner and scribbled it down. It was when the band saw the words, and realised that it was a description of himself, that they began to get seriously worried.

They also had an unfinished version of ‘Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun,’ first started back in August 1967. On January 11, it was resurrected and several sessions were devoted to working on it. David overdubbed most of the guitar on the final version but just enough of Syd remains – Gilmour: “A tiny bit” – for it to stand as the only recorded example of the five-man Pink Floyd line-up, albeit through the marvels of multi-track tape. This was Roger’s best composition to date; he spent four months working on it before presenting it to the band.

Unsure of himself as a lyricist, he used Syd’s technique and appropriated all the words from ancient Chinese poetry: The line “Little by little/the night turns around” is the second line of an untitled poem by the late Tang period poet Li Shang-yin (AD 813 – 858) which reads: “Watch little by little the night turn around.” Another of Li Shang-yin’s untitled poems is the source of “One inch of love is one inch of shadow” and “Counting the leaves which tremble at dawn” comes from his poem ‘Willow’. The poem, ‘Don’t Go Out Of The Door’ by Li Ho (AD 790 – 816) provided the line “witness the man who raved at the wall/as he wrote his question to heaven” – and so on. The title of the number is taken from Michael Moorcock’s sci-fi novel Fireclown*

Roger: “It was one of my first songs of Pink Floyd, and one of my first compositions. Actually, it was my first composition to be recorded. It is a piece of Chinese poetry. In truth, the only phrase of mine is the heading. All the remaining lyrics were practically lifted from this Chinese poetry.”

David: “By the time Syd left the ball had definitely stopped rolling. We had to start it all over again. Saucerful Of Secrets, the first album without him, was the start back on the road to some kind of return. It was the album we began building from. The whole conception of Saucerful Of Secrets has nothing to do with what Syd believed in or liked.”

There are reports that Syd sat, guitar in hand, in the lobby of EMI Studios, day after day, waiting for the band to invite him in to contribute. It is hard to imagine that they would have been un-moved by this and not have at least installed him in the control booth.

After Syd left, Roger Waters took over as the band’s main songwriter.

Saucerful was a transitional album, part Floyd Mark I, part Mark II, and most of all, a transition between a singles band with a penchant for extended avant-garde improvisation to a more melodic band interested in creating sound sculpture and atmospheres. Another factor to contend with was producer Norman ‘Hurricane’ Smith who was still intent on producing three minute singles for EMI. The idea of a band that didn’t release singles was beyond his comprehension and it soon became clear that his commercial pop approach was anathema to their non-commercial ‘progressive rock’ direction.

Rick: “We were pretty cocky by now and told him ‘If you don’t want to produce it, go away.’”

The lengthy title track instrumental could have easily not happened. The band had put together a reasonable second album so Smith graciously allowed them a bit of space at the end of recording to do what they liked as a reward.

Roger: “It was the actual title track of A Saucerful Of Secrets that gave us our second breath. We had finished the whole album. The company wanted the whole thing to be a follow-up to the first album but what we wanted to do was this longer piece. And it was given to us by the company like sweeties after we’d finished. We could do what we liked with the last twelve minutes.”

The track gave them new confidence.

Roger: “It was the first thing we’d done without Syd that we thought was any good.”

According to David, Nick and Roger approached the song “as an architectural diagram, in dynamic forms rather than in any sort of musical form, with peaks and troughs. That’s what it was about. It wasn’t music for beauty’s sake, or for emotion’s sake. It never had a storyline. Though for years afterwards we used to get letters from people saying what they thought it meant. Scripts for movies sometimes too.”

Gilmour told Guitar World: “‘A Saucerful’ was inspired when Roger and Nick began drawing weird shapes on a piece of paper. We then composed music based on the structure of the drawing … We tried to write the music around the peaks and valleys of the art. My role, I suppose, was to try and make it a bit more musical, and to help create a balance between formlessness and structure, disharmony and harmony.”

They created the track in the studio from scratch, improvising and building the layers of sound until they got it right. It was a thrilling, exciting, experience but not everyone liked it. Norman Smith was appalled.

Rick: “He just couldn’t – he didn’t – understand. He said, ‘Well, I think it’s rubbish. It won’t sell a single copy, but go ahead and do it, if you want’ sort of thing. Whereas we all believed it was gonna be one of the best things we’d ever put onto record. Which I think it was at that time.” Everyone within the band recognised that they had done something significant with ‘Saucerful’. Nick said that it was the key to “helping sort out the direction we were going to move in. It contains ideas that were well ahead of the period, and very much a route that I think we have followed. Even without using a lot of elaborate technique, without being particularly able in our own right, finding something we can do individually that other people haven’t tried … like provoking the most extraordinary sounds from a piano by scratching ‘round inside it.”

David: “That was the first clue to our direction forwards, from there. If you take ‘Saucerful of Secrets’, the track ‘Atom Heart Mother’, then the track ‘Echoes’ – all lead quite logically towards Dark Side Of The Moon.

After they finished recording, Norman Smith told Floyd roadie Pete Watts: “After this album they will really have to knuckle down and get something together.” There was never a sudden break with Smith; no big argument, but after Syd left he seemed to be less and less interested in the direction the band were taking. Though he had found Syd difficult, if not almost impossible to deal with, he always saw him as a commercial artist and could see no one else in the band likely to write a chart topper.

‘He just couldn’t – he didn’t understand. He said, ‘Well, I think it’s rubbish. It won’t sell a single copy, but go ahead and do it, if you want’ sort of thing. Whereas we all believed it was gonna be one of the best things we’d ever put onto record.’

Rick Wright

The professional partnership between band and producer drifted apart naturally; the Floyd appreciated how much Smith had taught them about using a studio; many producers at that time were very secretive about the mysteries of the mixing desk and the tangle of patchcords that were used to connect the Dolby sound reduction units making that end of the studio look like a telephone exchange. He allowed them to watch during tape reductions and mixing and let them produce a track he had no empathy for – ‘A Saucerful Of Secrets’ – themselves. By the time of Ummagumma a year later the Floyd felt confident that they no longer needed Smith’s expertise.

Saucerful ends with Barrett’s remarkable ‘Jugband Blues’, recorded in October 1967 when he was still relatively active in the band, with its eerily knowledgeable lyrics about his own condition, as if he could see what was happening to him and yet could do nothing about it. Addressing the band he sang: “It’s awfully considerate of you to think of me here/And I’m most obliged to you for making it clear that I’m not here.” The last line of the album, the last line of Syd’s career with Pink Floyd asked: “And what exactly is a joke?” It is one of his greatest songs, and one of his most experimental tracks.

One of the few conversations I had with Syd that I can remember anything about was regarding the Beatles track ‘A Day In The Life’. I had been at several of the sessions for it and Syd was intrigued to hear about Paul McCartney’s instructions to the orchestra to play 24 bars, beginning at the lowest note in their instrument’s register, and ending 24 bars later at its highest. How they got there was up to them. The orchestra were horrified not to have a written score but managed it. I think that this was in Syd’s mind for ‘Jugband Blues’ when he demanded that Norman Smith bring in a brass band who were instructed to “play whatever you want.”

Smith had produced an album by the Salvation Army Band of north London and dutifully brought them in but he could not bring himself to allow them to play free-form. Normally he and Syd had little to do with each other; Syd went his own way and changed his songs and music at every whim, much to Norman’s irritation. This time, however, it boiled over into a full scale row. After half an hour Syd got fed up and walked out, leaving Smith to finish the track as best he could. He got them to play a bit of free-form, and a bit of oom-pah music as well, just to make his point. The pointless stereo swings from the left to right channels were also his, the Floyd were only present for the mono mixing.

On February 12 and 13, as part of the Saucerful sessions, the Floyd recorded Rick’s ‘It Would Be So Nice’ and Roger’s ‘Julia Dream’; originally respectively titled ‘It Should Be So Nice’ and ‘Doreen’s Dream’, the latter being the first Pink Floyd song to be recorded with David Gilmour on guitar and vocals. It was released as a single on April 12 in advance of the album but went nowhere. The band was not surprised. Nick Mason later commented: “Fucking awful that record wasn’t it? At that period we had no direction.” Without Barrett, they were not a singles band – a fact brought home to them even more clearly with their next single – their last for more than ten years – ‘Point Me At The Sky’ and ‘Careful With That Axe, Eugene’ released on December 17 that same year, 1968, which again did not sell and the Americans did not even bother to release.

Peter Jenner and Andrew King had always backed Syd as the creative force in the Pink Floyd and just could not see the group surviving without him. There was little evidence that the others could write; the only example was Roger’s appalling ‘Take Up Thy Stethoscope And Walk’ on Piper. The pair had also backed Syd in his struggle to remain in the group, assuring him that he was the creative genius. It was inevitable then, that when Roger, Nick and Rick decided that Syd had to go, there would be dissension from Jenner and King when they heard about it. At first the group did not tell them that they were no longer taking Barrett to gigs, nor did they reveal the addition of Gilmour to their line-up which came as a complete surprise to the management team.

As the Pink Floyd management was a six-way partnership, the band members did not have a clear majority, but according to Nick the breakup, when it came, was remarkably civil. Peter and Andrew opted to manage Syd and did not feel that the rest of the band stood a chance. A meeting was held on March 2 with all parties present (including Syd) and the six-way partnership was dissolved, with Jenner and King keeping Blackhill Enterprises and an agreement made that they would receive 20% in perpetuity of all income arising from recordings made during their tenure. The band took over the hire purchase payments on their equipment, and with the band’s bookings already being arranged by the Bryan Morrison Agency, they asked Morrison to manage them.

Nick remembers that Syd’s contribution to the meeting was to suggest that two girl saxophone players be added to the Floyd lineup.

* The soundtrack to an obscure colour film short showing the group (with Syd) miming the song in a studio setting – Wright and Waters playing wind instruments during the demented Salvation Army break. The clip was made by, of all things, the Central Office of Information.

* Also published as The Winds Of Limbo.