In search of Shangri La

Several countries claim to be the seat of Shangri La, the mythical mountain paradise, cut off from the world and from time. It is of course an ancient tale, but it was given a name by James Hilton in the poignant novel Lost Horizon, which was published In 1933, even as the Japanese were running amok in much of East Asia and clouds of war gathered over Europe. The Chinese claim it on behalf of their reluctant charge, Tibet. The Nepalese do too, even as their country sinks into violent internal conflict. In Hilton's book, Shangri-La is a Buddhist monastery, its inhabitants are opposed to all violence and materialism, and all the wisdom of the human race is stored within its borders. But perhaps the true Shangri-La is not a place, but a state of mind. In which case it Is perhaps still necessary to visit the tiny kingdom of Bhutan, high in the Himalayas.

Khudunabari camp in Jhapa, one of the seven created by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), perches on the border between Bhutan and Nepal.

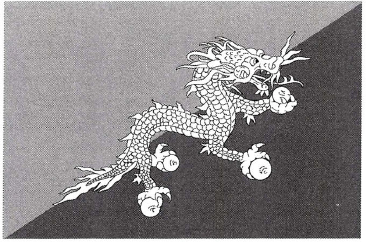

Bhutan itself is squashed between India and China and the British artificially created its “monarchy” in the early years of the 20th century. It is mostly mountainous, and violent storms from the Himalayas give the country its name, which means, “Land of the Thunder Dragon.” Fascinatingly, It has adopted a New Age strategy of raising not its Gross Domestic Product, the conventional person's national measure, but its “Gross National Happiness” instead.

Bhutan, according to the King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, needed to concentrate on sharing its rather limited prosperity, rather than increasing it. It also needed to protect its culture, its environment and its animals. An article in Le Monde in 2005 reported an international conference marking its success at achieving this, noting that while individual incomes in the country remain as low as anywhere in the world, life expectancy has increased since 1984 from a disgraceful 47 years to a respectable 66. (Although the CIA World Factbook records it as only 55.) A new constitution demands that some 60 percent of the country be left to trees, and that the number of tourists be limited. As Thaku Powdyel, an official at the Ministry of Education, explained, “The goal of life should not be limited to production, consumption, more production, more consumption.”

Bhutan is a good internationalist too. It has joined the Biodiversity, Climate Change, Kyoto Protocol, En-dangered Species, and Hazardous Wastes global conventions, and signed, but not ratified, the Law of the Sea. Although we might forgive the omission, since Bhutan Is entirely landlocked and has no navy or ships.

Curiously enough, for such a happy country, Bhutan seems to qualify as the country with the highest proportion of its population living as refugees outside its borders. Some 100,000 Bhutanese of Nepali origin fled the country in the 1980s when the religiously and ethnically distinct ruling class (the “Drukpas” who are a kind of Buddhist, arranged in clans with the King at their apex), passed laws imposing its own language, dress and culture, not to mention compulsory redistribution of land and occasional disenfranchise-ment. These refugees now live in camps in Nepal, run by the UN.

In its tireless pursuit of happiness, in Bhutan it is often compulsory to dress up as a Buddhist—for example when visiting monasteries, or in order to go to government offices, even to schools on certain days. Subversive books, such as non-Buddhist religious texts, have long been forbidden, and there is only one government-run “Buddhist” newspaper. Since 1989, foreign TV and satellite dishes are forbidden too. The jails are full of prisoners convicted of what are classed as “anti-national” criminals, who may or may not be tortured there. Buddhists believe that suffering is part of life, after all.

Evidently if the happiness of these long-term refugees had to be counted into the “GNH” of Bhutan, there is a risk that the all-important “headline figure” for GNH would have to be adjusted downwards. And carrying even a text like this into the happy kingdom might incur a prison term.