The summit of the Mao Trail

Fly to Beijing. Get a moto-rickshaw to the Square.

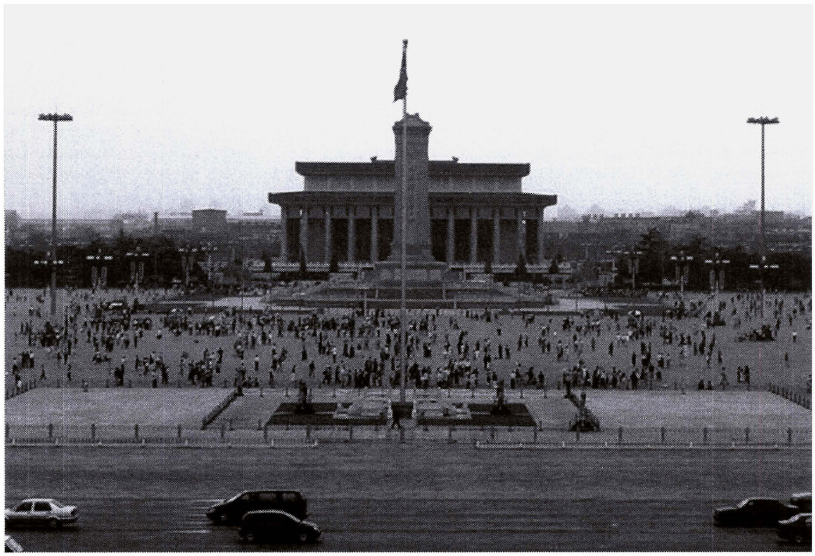

Beijing. Tiananmen Square. The name is now synonymous in Western minds with the events that unfolded here in 1989, but the ill-named Square of Heavenly Peace—the largest public square in the world (2,887 feet by 1,640 feet, or 880 meters by 500 meters)—has been at the very heart of Chinese history for centuries. Since the Ming Dynasty this has been where emperors would issue decrees to their subjects. And indeed, it was the place that Mao came to make all his pronouncements, such as that heralding “Great Leap Forward,” which unfortunately resulted in the collapse of agricultural production and mass starvation in the countryside. Or there was the Cultural Revolution, which unfortunately resulted in complete anarchy, the collapse of education and manufacturing, and (again) mass starvation in the countryside. Nonetheless, an impressively large portrait of the late Chairman smiles benignly down from the Gate of Heavenly Peace (over the increasingly capitalist Chinese people). And it is here that the Great Helmsman finally came to rest, in a tomb known as the Maosoleum (no kidding).

If Mao's house is a little too easy to visit, Mao's tomb is a substantial wait. Even first thing in the morning, a line will snake around to the southern side of the square.

Under Maoism, life expectancy in China rose from 35 years in 1949, to 68 years at the time of his death. This undoubtedly was a “great leap forward.” In such a poor nation, the approach was based on education and prevention, and some older Chinese people can still recite a poem Mao wrote about schistosomiasis and the successful eradication of the water snail responsible for it.

How dangerous is Tiananmen Square? According to China's own official Academy on Environmental Planning it is, like the rest of Beijing, “very dangerous.” However, the real risk, whatever the views of Western Human Rights monitors, is not from People's Revolutionary tanks, but from much more mundane vehicles.

For if visitors used to marvel at the throngs of thousands upon thousands of bicycles in Beijing, proceeding chaotically but yet systematically across the city's wide boulevards, now Beijing is famous for another reason. Invariably covered in a blanket of yellow smog, it now claims the world's most dangerous levels of carbon dioxide. Since the year 2000, the number of vehicles clogging the capital's streets has more than doubled to nearly 2.5 million. It is expected to top the 3 million mark just in time for the Olympics in 2008. China is already the world's second largest producer of greenhouse gases (the United States is the top) and on a World Bank list of the planet's 20 most air polluted cities it features 16 times.

Acid rain now falls on a third of China's vast territory, as well as many of its neighbors, and 70 percent of rivers and lakes are no longer safe for drinking. Government policy, as in the West, is to prioritize road building and even to ban bicycles from certain routes. It is a surprisingly uncritical endorsement of the development strategies of the disastrous car-friendly economies of the capitalists. The political implications are also becoming apparent as serious health issues emerge. Scores of birth defects are being linked to chemical factories and have been a significant factor in recent waves of popular protests.