Ripping yarns of squatter towns and drug wars.

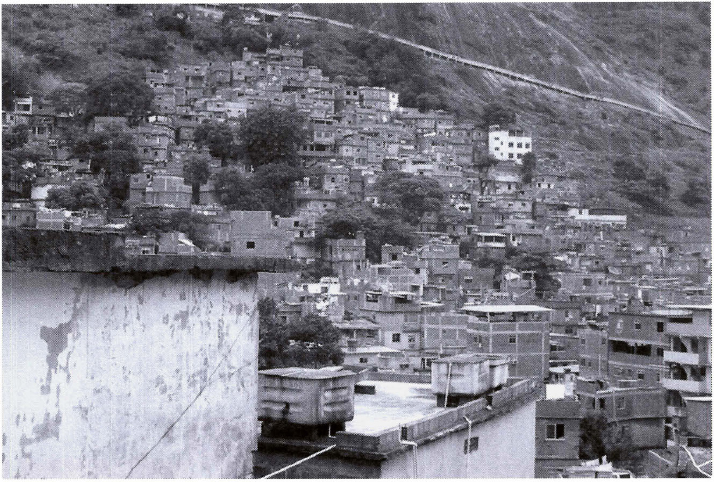

Fly down to Rio, where Favela Tours organizes visits to areas like Rocinha, Brazil's largest “favela” or squatter town, with a population of over 150,000 people squashed into an area of only one square mile. Here the tin shacks are piled one upon the other. As government policy originally was to wait for the squatters to move on, they typically lack services like drinking water, electricity and of course, sewage. There are hardly any jobs or schools, and they are havens for crime, especially drug crime. Until recently the government largely ignored them. But now, they have begun to get attention. The government is rooting out the criminals, putting in services, and most importunely, the favelas are now on the tourist circuit.

One visitor, Wendy O'Dea, explains why:

I knew what most people know about this city: it's full of long, beautiful beaches with sun worshippers in tiny swimsuits, the people are vibrant and beautiful; and the city knows how to throw a serious party about this time each year, Rio's infamous Carnaval. I didn't know that in Rio I could find some of the best sushi I've ever eaten, soar through the air in a city that is one of the world's best for hang gliding, and stroll through run-down slums—mini cities within the city that house a subculture that is both frightening and fascinating.

For tourists driving from Rio de Janeiro airport to the center of Rio not only immediately see the famous view of Sugar Loaf Mountain and Christ the Redeemer, but also the less celebrated views of the squatter towns, clinging to the rocky hillsides.

Here the mean buildings are pockmarked with bullet holes and armed gangs of bandido youths patrol the streets at night looking for rivals to blast away. To mark out their territories, the gangs lay concrete pillars or burnt out cars across the streets, and paint murals on the walls. The emblem of choice these days is, of course, Osama bin Laden.

If you're lucky, you may find someone to tell you about the system:

The chief of the traffic [gang] called everybody together and there was a long conversation from midnight until 3 am. It was decided that one of the gang had broken its rules. “We shot him right there, in the school. He just kept quiet. He knew he was going to die . . . First we shot him, then used an electric saw to cut him up and put parts of him in a suitcase. His torso was left in the road. It is a way of imposing respect.” Other informers are frightened and the community knows not to grass.

It sounds pretty bad, but even if there are an estimated seventeen million illegal weapons in Brazil, “they are used in confrontations with the police or other bandits. They are not used to assault you on Copacabana beach”—or at least according to Antonio Rangel Bandeira, the coordinator of the arms control program in the city.

Tour guides echo this sentiment, telling their clients, “You're completely safe when you're in a favela. The violence that takes place in the favelas is not directed at tourists.”

The reassurances would have been better both if there had not been so many of them, and if I hadn't just happened to read, in the newspaper, under the heading “Rio de Janeiro,” about a thirteen-year-old girl who had just confessed to flagging down a bus. Now this, in itself, is not such a bad thing, but it had been part of an attack ordered by a drug baron, and her gang mates had poured gasoline over the bus, blocked people from getting off, and set it alight. Five travelers died.

And in any case, the rules about only targeting gang members do not apply to the police, who are notoriously corrupt in Brazil, do not respect the “beach code,” and will shoot people anywhere. In 2003, the state police killed 1,195 civilians during operations. And this is a common theme in South America where the war on drugs, like the war on terror elsewhere, seems to have removed all constraints on the so-called security forces.

Perhaps thinking of this, one guide tells visitors confidentially, “I brought a tour by this corner not long ago—and there was a long line of police at the intersection. Concerned, I slowed down to inquire if there was a problem and the policeman told me there was no problem—they just really liked the food!”

So it seems these tours are safe enough. But is it really ethical to pay money to look at poor people? Wendy says that, “Admittedly, it did feel somewhat voyeuristic, but most people went about their daily business—hanging laundry, shopping at the daily street markets—paying little attention to the foreigners slipping in and out of their midst.”

Anyway, the tourists were reassured to learn that part of the day's fee of about $20 goes towards sponsoring local schools.

An art house film, Ciudad de Deus (City of God), is set in these self-same drug-ridden slums. It is not likely to generate much business for Favela Tours as it is unrelentingly violent.

But hang gliding is dangerous, regardless of where you are.