CRITIC ESSAY

ROAD HOUSE 1989

38%

38%

Directed by Rowdy Herrington

Written by R. Lance Hill and Hilary Henkin

Starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara

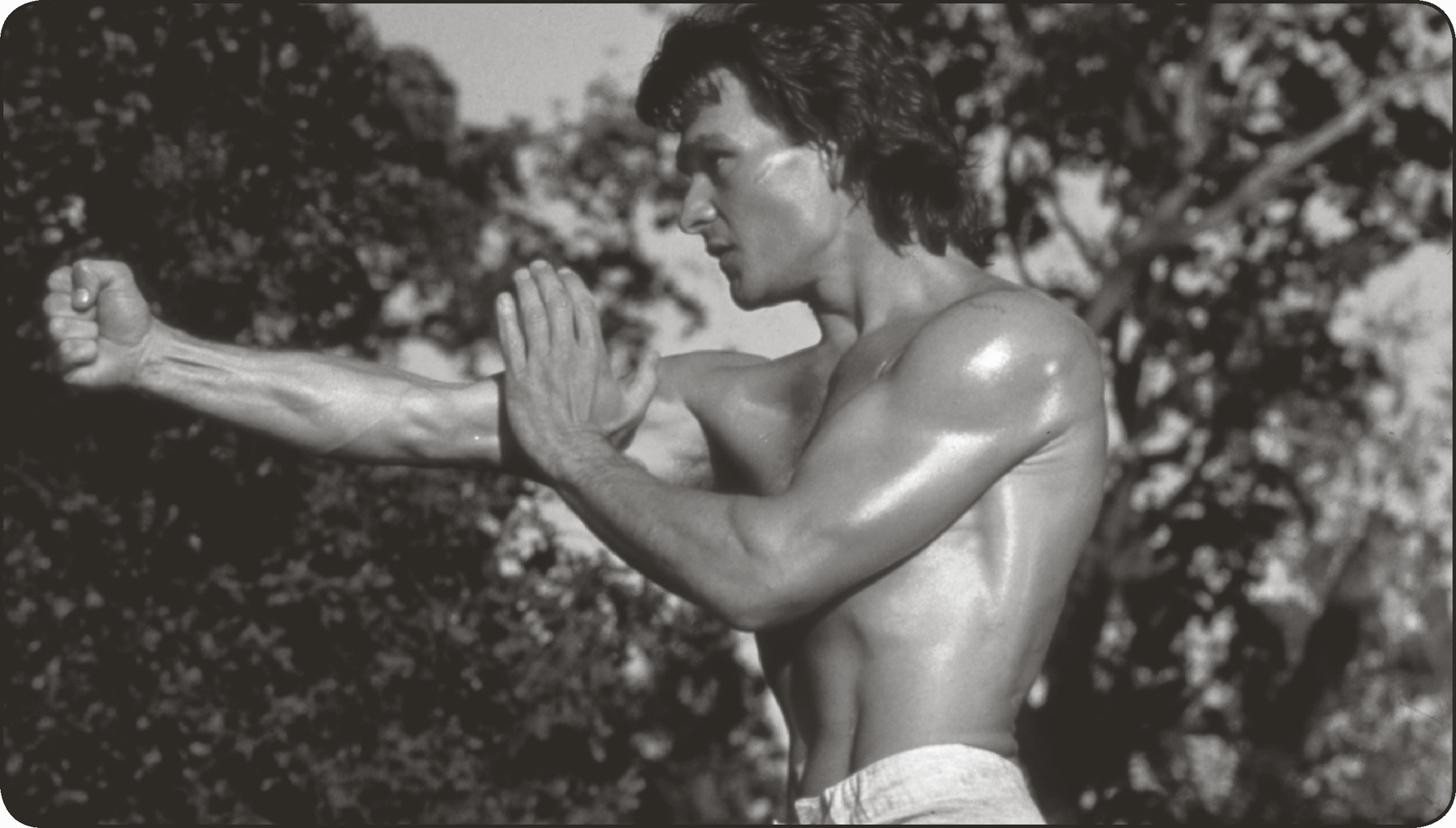

Of the treasures of 1980s action begging to be unleashed from the vaults like a pumped-up bicep aching for a fistfight, none hold quite as special a place in movie history as Road House—a film filled to the rafters with brawls, boobs, rock ’n’ roll, a safari-hunting sadistic land baron who loves to party, and the lithe, leonine Patrick Swayze at his Swayziest.

Arriving in theaters in the summer of 1989, Road House would go on to earn scorn from critics, modest ticket sales, and five Golden Raspberry nominations. Only time and robust home video rentals would prove its cache as a cult classic, thanks in no small part to Swayze’s committed turn deconstructing hypermasculinity with cool-guy flair and that oiled-up beefcake bod, terrain he would revisit two years later in the seminal action bromance Point Break.

But those who only appreciate Road House from behind a “so bad it’s good” veil do it a disservice. Because even when it misfires, the film cranks everything to eleven—an act that itself lays endearingly bare the mortal limits of the creative process.

And Road House is a prime example of just how human movies can get: while probing the precarious balance between peace and violence that lives within us, it is also a delightfully over-the-top picture (directed by a guy appropriately named Rowdy Herrington) about a hunky pacifist haunted by the fact that he just can’t seem to stop ripping out the throats of his enemies. (Well, can you blame him? Sometimes you’ve got to rip a few throats to save a small town from ruthless, ascot-wearing crooks… amiright?)

That Road House can be many things at once is key to its unique poetry.

With nods to Wild West icons in a script by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Romeo Is Bleeding, Wag the Dog), Road House takes place in a flyover country hamlet caught in the economic crossfire of a changing America. It’s here in Jasper, Missouri, that Tai Chi–practicing Dalton (Swayze), an uber-bouncer with a violent past and a philosophy degree from NYU, arrives from the big city to clean up the Double Deuce, a lawless roadside joint where brawling bikers, strippers, drunks, and corrupt bartenders are driving business into the ground.

Spouting pseudo-Buddhist aphorisms like “Be nice until it’s time to not be nice,” the preternaturally Zen Dalton trains a motley security crew, tosses out the bad eggs, turns the Double Deuce into a hot spot, and romances local doctor Elizabeth “Doc” Clay (Kelly Lynch), all while gazing upon the nightly crowd from his watchful perch, black coffee in hand, always one step ahead of trouble.

That is, until Dalton discovers the townsfolk are being terrorized by rich Chicago douchebag Brad Wesley (a delicious Ben Gazzara), which is when Road House turns into a Mid-Western showdown and our hero is put to the test: Can he stop Wesley and save Jasper—without tearing out another man’s jugular?

The heightened, deadpan stakes are just a few of Road House’s many charms; hilariously convenient geography is another (evil Wesley lives right across the river from Dalton’s converted barn bachelor pad, within peeping view of our hero’s gravity-defying lovemaking sessions).

One must applaud the genius in assembling such a zesty cast, which includes pro wrestler Terry Funk and X punker John Doe as evil henchmen; blues rocker Jeff Healey as the leader of the Double Deuce’s house band; and Missouri’s own legendary Bigfoot monster truck, a beast that destroys its way through a car dealership in a scene that reportedly cost $500,000 to stage and could only be filmed once, for obvious reasons.

Meanwhile, bringing charisma to Jasper’s exasperated band of townies are actors Kevin Tighe, Red West, and Sunshine Parker, while Kathleen Wilhoite and a blink-and-you’ll-miss-him Keith David help ground the ensemble around Swayze. Sam Elliott nearly steals the show as Dalton’s charming mentor Wade Garrett, the O.G. cooler who breezes into town to help his protégé battle Wesley’s goons.

Like catnip for muscular eighties action lovers, every fiery slo-mo explosion, massive bar brawl, and bone-smashing martial arts fight is lensed with a meaty vibrancy by cinematographer Dean Cundey (Back to the Future, Jurassic Park). Like all Joel Silver productions, it’s the stuff thirteen-year-old boys’ dreams are made of—for better and worse. Most fascinating is how Road House seems, at times, to be at war with itself.

After countless saloon scuffles and macho one-liners, despite unfolding at a rollicking pace through its first two acts, Road House careens off the rails once Dalton regains his taste for blood. As he becomes unmoored, so does the film. Few movies ratchet to such extremes as Road House’s over-the-top third act, which is when Herrington really turns on the gas.

You can track the shift in Swayze’s increasingly frenzied face, in one of the fastest onscreen escalations of chaos committed to cinema. One minute, Dalton’s a feathered-hair philosopher warrior reading Jim Harrison paperbacks in the moonlight—not terribly far removed from Swayze’s Dirty Dancing heartthrob, if Johnny had a talent for breaking up bar fights instead of wooing divorcees. The next, he’s a sweaty, shirtless maniac, tackling baddies off speeding motorcycles and doling out roundhouse kicks with the pointed-toe precision of a dancer. It’s a role only Swayze could play, blessedly committed as the body count skyrockets and Dalton’s moral compass implodes. More shockingly unpoliced killings will plague this small Missouri town before Dalton, and the movie itself, will know the true meaning of “enough.”

As he says early in the film: “Pain don’t hurt.” Then again, he might come to find that wisdom might not apply to the existential kind. With time, Road House’s zany flourishes have become battle scars it can wear with pride, a survivor of its own bombastic excess—not a film so bad it’s good, but a film that dared to be so extra, it’s great.

Rotten Tomatoes’ Critics Consensus Whether Road House is simply bad or so bad it’s good depends largely on the audience’s fondness for Swayze—and tolerance for violently cheesy action.