One

The problem with Black males

I met “Blue” one day about 20 years ago, in the living room of the apartment that I shared with my fiancée. At the time we were pursuing our graduate studies at the University of Chicago. Blue was a laborer hired by the movers whose services I secured to transfer our belongings to western Massachusetts. Our move to Northampton, Massachusetts would allow my fiancée and me to spend our final year of graduate study on fellowships at neighboring liberal arts colleges in that region (at Smith College and Hampshire College, respectively). Blue was an African American male who appeared to me to be in his mid-thirties. At first sight, not much was particularly distinctive about him. I could not know it at the time, but the story Blue told me would become one of my signature testimonies of the ultimate possibility for Black men in the United States.

The husband and wife team that the moving company sent to us brought along Blue to help with packing and loading on the front end of the move (Massachusetts-based help would unload at the back end). At close to six feet in height, Blue was not very stocky yet he was solidly built and seemed quite capable of doing his job. My fiancée and I observed the moving team pick up various items, maneuver them to the elevator, and then down to the truck. Blue seemed especially focused on moving our bookshelves and office furniture, which was an especially relevant skill set given that my fiancée and I had acquired much of such material over the course of our six years of graduate study.

At some point during their work I overheard the husband tell Blue that he seemed to really know how to handle office furniture. He responded that office moving was his specialty. “I know how to do office,” is how he explained himself. Having never before hired, much less even observed professional movers in action, I found myself drawn to the manner in which Blue worked. He positioned file cabinets at particular angles prior to moving them, and he tilted bookcases in ways that made them seem especially maneuverable. He seemed to work hard at making moving look easy.

At about mid-afternoon the team took a break for lunch. Blue grabbed a sandwich and a drink out of a paper bag and sat on the floor of my now semi-bare living room. Having heard much of Blue's conversations with the moving team throughout the morning, I knew he was from the south side of Chicago, a residential area almost exclusively occupied by low-income African Americans who were struggling to achieve the American Dream. Having ventured into that part of town for research purposes, I knew that Blue was from a community where many Black men in particular found their way into illicit activities, as well as into the gangs that regulated them. I was keenly interested in this man who had what I regarded as a unique job and who was from an area of the city that had no shortage of African American males without jobs of any sort.

I plopped down next to Blue while he was eating and asked him how he found his way into the moving business. In between bites of his sandwich Blue told me his story. He said, “When I was younger I was a very bad boy.” He told me how he was involved in gangs and the traditional activities that gangs in Chicago immersed themselves in. Blue sold drugs. He stole merchandise. He helped plan and participate in attacks on rival gang members. In short, he represented the kind of public menace that appears in the minds of many people when they think of what is wrong with Black men.

He explained that his commitment to a wayward path was interrupted by his uncle. One day when Blue was in his late-teens his uncle told him that he needed to get out of the streets or the streets would take control of him. In order to make this happen his uncle told him to pack his bag. Blue was going to be traveling with him for a few weeks. Blue told me that he knew that his uncle drove a truck for a living, but he did not know much else about what he did.

Blue packed his bag and joined his uncle. He soon found out that the travel would first involve helping his uncle load up a truck full of household goods from a small home in Chicago. Once the truck was loaded, Blue hopped in and his uncle drove the two of them to Florida with the material in tow. Blue told me that this was his first trip outside of the city of Chicago.

“I saw green grass and trees and fields,” he told me. “And I saw small towns that did not have lots of people in them.” He also said, “I saw places where Black and White kids played together, and everybody seemed to be having fun.” He said, “It all was so different from Chicago.” His manner of speaking made it almost feel like he was telling a fairy tale.

After they arrived in Florida, Blue helped his uncle unload the truck at a small house there. When they were done Blue asked his uncle, “What are we going to do now?” His uncle told him, “We are going to go someplace else, pick up some more stuff, and take it somewhere else.” That was Blue's introduction to professional moving. Indeed, it was his first experience with formal work. As importantly, it was Blue's first-hand exposure to social worlds far beyond and very different from inner-city Chicago.

I have thought about Blue quite often since hearing his story more than two decades ago. The move he made from unemployed gang member seemingly locked into a closed world on the south side of Chicago to a man who encountered parts of the United States that severely contrasted with what he experienced in his Chicago neighborhood. Among many other factors (the social support provided by his uncle not an insignificant one), this exposure allowed him to reconstruct a vision of himself, his social world, and his potential place within it.

When I met him he was by no means financially secure, but he was secure about knowing what he could do with himself and what he wanted to do in the future. He wanted to own his own truck. This would enable him to have control of his involvement in professional moving. He told me that he was several years away from making this happen, but he had mapped out a plan for securing his future. The first part of the plan was demonstrating his indispensability as a packer and loader so that he could establish an identity as a good employee. The plan also included saving money to invest in a small truck.

At first sight, I had no idea that Blue was a former gang member who lived his teenage years quite unfocused on his future. Instead, I saw a man who knew how to get his job done, and his abilities greatly impressed the people that hired him for that day. He also knew what so many of the near 500 men that I have interviewed in the course of my research on low-income, urban-based Black men did not know, which is what parts of the world look and feel like that are far removed from the kind of disadvantaged communities where many struggling Black people reside.

More than 20 years have passed since my conversation with Blue. Since that time, I have continued to wonder what capacity many Americans have to imagine how someone like Blue became the person that he did given the life he led since his youth. What capacity, I question, do they have to envision any socio-economically disadvantaged Black man as a potentially positive individual?

Not every Black man living in socio-economic constraint can benefit from an uncle capable of delivering the kind of opportunities that Blue's could. Yet, the importance of Blue's story is not simply that his uncle, another Black man, acted on his behalf. It is also that Blue acted on his own behalf to learn and plan a future for himself given what his uncle had exposed him to. The importance of Blue's story can be lost if framed solely as a heroic tale of moving from desperate living to the verge of possible stability if not wholesale success. His story accounts for how a Black man can typify the crisis of Black men when viewed from one vantage point, but who appears to be wholly capable of serving himself and serving others when viewed from the vantage point of my living room.

The kind of man that Blue was in his adolescence and early adult years was the kind that I have consistently studied over the past two decades. The kind of man that Blue became by the time that I met him exemplified my hopes for the men that I have studied. In the same way that I could not see his past without him telling me all about it, Americans often do not see new possibilities for Black men because of what they witness and interpret about their present condition. Admittedly, seeing new possibilities is not easy. Creating such a vision, however, first means taking careful account of the present-day realities for these men. This must be done not to cement preconceived notions about them, but rather as a precondition for imagining them differently.

* * * * *

Long-standing preconceived notions about Black men have not emerged in a vacuum. Instead, this problematic portrait is tied to various social outcomes and processes, and these should not be ignored. They concern the health, employment, and educational status of these individuals. A quick overview of this landscape is necessary in order to demonstrate precisely what these men must work against, and what the rest of us must realize and consider, in the quest for them to be regarded in a better light.

In 2015 The New York Times published an article indicating that more than 1.5 million Black men in the US were missing (Wolfers et al. 2015). The article was not about mass-scale abduction, but rather about the removal of these men from residential communities and workplaces. To be exact, their disappearance was due to premature mortality (approximately 900,000 men) and incarceration (in the region of 625,000 men). Consequently, for every 100 Black women not in jail, there were only 83 available Black men, or 17 missing Black men for every 100 Black women. The authors of this report also stated that among White Americans there is only one missing man for every 100 women. The case of missing Black men triggers attention to various measures and indicators of the problem with Black males.

Men in general, but certainly Black males, account for their sense of manhood by their ability to perform as family providers, husbands, fathers, employees, and community members (Hammond and Mattis 2005). However, a litany of social scientific and other research has given credence to the notion that a crisis for Black men abounds, and their invisibility or nominal presence in many spheres of social life has been well documented. The statistics do tell a compelling story. The first story to report is exactly who constitutes the population of Black men in the US (see table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Black men, population at a glance

Source: BlackDemographics.com, 2013.

| Black men | All men | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 21.5 million | 151.7 million |

| Median age | 31 | 36 |

| Percent compared to females | ||

| Under 18 years of age | 48% | 49% |

| 18 to 34 | 51% | 51% |

| 35 to 64 | 47% | 49% |

| 65 and older | 40% | 44% |

According to census data, the Black male population in the United States makes up 48% of the total Black population. Black males are on average younger than other males in the United States (31 years old compared to 36 years old for “all males”). The higher mortality rate than males on average means that the percentage of the population who are males declines much more quickly for Black males as they get older.

Health and physical well-being

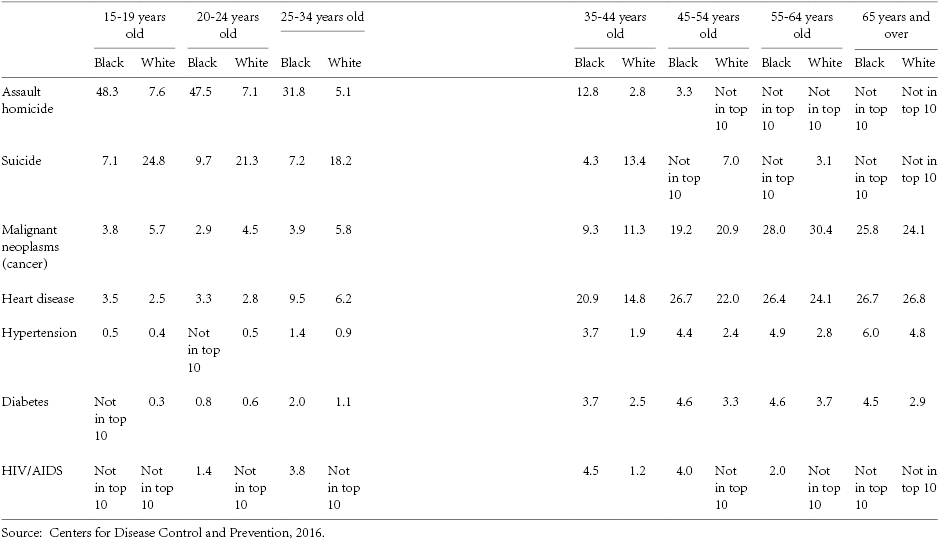

In 2006, the homicide death rate for young African American men was 84.6 per 100,000 of the population compared with 5 per 100,000 of the population for young White men. While homicide death rates decline for older African American men, the rates among African American men aged 25–44 are still disturbingly high (61 per 100,000 of the population) when compared with Whites of that age group (5.1 per 100,000 of the population) (Kaiser Family Foundation 2006). In 2006 it was found that Black males aged 15–19 die from homicide at 46 times the rate of their White counterparts (National Urban League 2007). As table 1.2 indicates, in the years to follow, reports of the health and well-being of Black males did not improve.

Table 1.2 Causes of deaths for Black and White males (%) (based on top 10 ranking, 2014)

Other measures of health and well-being for African American men are equally disturbing. In February 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a report assessing the lifetime risk of HIV in the United States. The report revealed that for heterosexual Black men in the US there was a 1 in 20 lifetime risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (compared to a 1 in 132 lifetime risk for White heterosexual men) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). Black men are similarly disproportionately affected by the HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic when compared to other population groups. Black men have more than seven times the AIDS rate of non-Hispanic White men. In addition, Black men are more than nine times more likely to die from HIV/AIDS than White men (Office of Minority Health 2008).

Furthermore, African American men have the lowest life expectancy and highest mortality rate among men and women in all other racial or ethnic groups in the United States. The life expectancy at birth is 70 years for Black men compared with 76 years for White men, 76 years for Black women, and 81 years for White women (National Center for Health Statistics 2007). The mortality rate for African American men is 1.3 times that of White men, 1.7 times that of American Indian/Alaska Native men, 1.8 times that of Hispanic men, and 2.4 times that of Asian or Pacific Islander men (Kaiser Family Foundation 2006).

Black men are 30% more likely to die from heart disease as compared with White men. The mortality rate for diabetes for Black men is 51.7 per 100,000 as compared to 25.6 per 100,000 for their White male counterparts (Xanthos et al. 2010). They also are 37% more likely than White men to develop lung cancer. Between 2000 and 2003, Black men had an age-adjusted lung cancer death rate that was 32% higher than that for White men (death rates of 97.2 versus 73.4 per 100,000, respectively) (American Lung Association 2007). Finally, in the 30–39 age group, Black men are about 14 times more likely to develop kidney failure due to hypertension than White men (US Renal Data System 2005), and Black men are 60% more likely to die from a stroke than their White adult counterparts (Office of Minority Health 2008).

Some of these data reflect the problematic ways in which Black men manage their health. Research has demonstrated that they are more likely than others to have undiagnosed and/or poorly managed chronic conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease (Warner and Hayward 2006; Williams 2003). Moreover, Black men, irrespective of their income level, are 50% less likely than White men to have had contact with physicians during the past year (Hammond et al. 2011).

Employment

African American males aged 16–64 had a lower participation rate in the labor force (67%) compared to “all males” (80%) (see table 1.3). Labor force participation refers to the percentage of men who were either working or looking for work. Males not in the labor force include those who may be full-time students, disabled, and others who are not looking or gave up looking for employment for other reasons.

Table 1.3 Earnings and employment

Source: BlackDemographics.com, 2013.

| Black men | All men | |

|---|---|---|

| Ages 16 to 64 | ||

| Percent who are in the labor force | 67 | 80 |

| Percent who are unemployed | 11.2 | 7.3 |

| Percent who are below the poverty line | 26 | 15 |

| Ages 16 and up | ||

| Median earnings for 2013 | $37,290 | $48,099 |

| Percent who worked full-time, year-round | 37 | 48 |

| Percent of earnings NOT from full-time work | 23 | 23 |

| Percent who had no earnings all year | 40 | 30 |

| Occupation type (%) | ||

| White collar | 42 | 75 |

| Blue collar | 26 | 17 |

| Service occupations | 23 | 8 |

The 37% of African American males who worked full time all year in 2013 had median earnings of $37,290 compared to $48,099 for “all men.” Of Black males aged 16–64, 40% had no earnings in 2013. This was higher than the 30% with no earnings of “all men” in the same age group. Also a larger percentage of Black males aged 16–64 were unemployed than “all men” and were living below the poverty line (26%) than “all men” (15%). Compared to “all men” in the United States, Black men who worked were much less likely to work in occupations that are considered white collar and were much more likely to hold blue-collar or service jobs. Only 42% of working Black men held white-collar jobs compared to 75% of “all men.”

Education

The greatest disparity between Black men and “all men” in the US is between those who have and those who do not have a bachelor's degree. Only 17% of Black men have a bachelor's degree compared to 30% of “all men” (see table 1.4). Second is the number of Black men who finished high school but did not pursue higher education (35% compared to 28%). While only 18% of Black men more than 25 did not complete high school, their percentage is higher than the percentage for men of all races and ethnic groups together. Other trends and statistics indicate the severity of the condition of Black males and educational attainment:

- According to 2012–2013 estimates of high-school graduation rates, 59% of Black men graduated from high school in comparison to 80% of White males who did so.

- These estimates reflect a 21 percentage point gap on the Black–White male high-school graduation rate.

- In 2009–2010 there was a 19 percentage point gap (Schott Foundation for Public Education 2015).

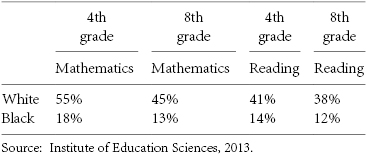

Problems abound for Black boys prior to the post-secondary experience. A recent report indicates that no more than 18% of Black boys perform at or above proficiency in reading and mathematics in the 4th and 8th grades, while no fewer than 38% of White boys perform at or above proficiency in the same categories (see table 1.5).

Table 1.4 Highest level of educational attainment (age 25 and above, %)

Source: BlackDemographics.com, 2013.

| Black men | All men | |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high-school diploma | 18 | 14 |

| High-school graduate (or GED) | 35 | 28 |

| Some college, no degree | 24 | 21 |

| Associate's degree | 7 | 7 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 17 | 30 |

| Attended college | 48 | 69 |

Table 1.5 Percentage of boys at or above proficiency by grade and subject, 2013

Incarceration

Of adults in 2001 who had ever served time in prison, nearly as many were Black males (2,166,000) as White (2,203,000), and this is out of a population of more than 20 million Black men in comparison to nearly 150 million White males. At that time, the rate of ever having gone to prison among adult Black males (16.6%) was more than six times as high as among adult White males (2.6%). An estimated 22% of Black males aged 35–44 in 2001 had at some point been confined in State or Federal prison, compared to 3.5% of White males in the same age group. Finally, as of 2001, about one in three Black males and one in seventeen White males are expected to go to prison during their lifetime, if current incarceration rates remain unchanged (The Sentencing Project 2013).

Over time the condition for Black males has not improved. In 2006 there were 1,502,200 male sentenced prisoners under State or Federal jurisdiction. Of these, 478,000 were White American males, representing 31.8% of the incarcerated population, and 534,200 were Black American males, representing 35.6% of the incarcerated population (The Sentencing Project 2013) – remembering, of course, the much greater number of White males than Black males in the general population.

The story is not dramatically better as we turn to contemporary data. In 2010 about 6% of Black men aged 18–64 were in State or Federal prison, or in a municipal jail. This is three times higher than the 2% of “all men” in the same age group. Moreover, approximately 34% of all working-age Black men who are not incarcerated are ex-offenders. This compared to 12% of “all men” who have at some point in their lives been convicted of a felony (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2010; Center for Economic and Policy Research 2010).

Finally, a recent report indicates that Black men constitute the largest percentage of men sentenced under the jurisdiction of State and Federal correctional authorities (36.5%) even as they constitute only approximately 15% of the male population in the United States (see table 1.6).

Table 1.6 Number and percentage of prisoners sentenced under the jurisdiction of State or Federal correctional authorities

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics 2015, and author's own calculations.

| Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| All males | 1,371,879 | (100) |

| White males | 446,700 | 32.5 |

| Black males | 501,300 | 36.5 |

| Hispanic males | 301,500 | 21.9 |

Fatherhood

In recent decades, high rates of unemployment, drug sentencing policies, and increased policing in urban centers have been linked to Black men's increased and disproportionate incarceration (Goffman 2014; Western and Wildeman 2009). Higher incarceration rates have led to many Black fathers rotating in and out of their children's lives. Their incarceration not only renders them physically unavailable but also limits their ability to offer financial and material provisions. The resulting strains to father–partner and father–child relationships result from the often unsatisfactory means by which family needs are fulfilled during fathers’ imprisonment (Swisher and Waller 2008; Western and Wildeman 2009). Black unmarried fathers face the additional financial burden of arrears, defined as the accumulation of unpaid child support, during their incarceration. Upon release these fathers encounter sometimes insurmountable arrears in addition to the prospect of paying current and future child support (Holzer et al. 2005). Further, they are challenged to readjust to society, find a job, and reconnect with their families.

By 2012, 55.1% of all Black children, 31.1% of all Hispanic children, and 20.7% of all White children were living in single-parent homes (US Census Bureau 2012). This is an increase from 2010, where the percentage for Black children stood at 48.5, and 2000, where the percentage for these children was 51.1 (US Census Bureau 2012). While these data do not reveal the extent to which Black men engage their children and invest in quality time, as the great majority of single-parent households are female-headed, they do affirm the physical challenges that Black fathers confront in being present with their children on a regular, if not everyday, basis.

* * * * *

The statistics are stunning. They effectively convey that a crisis exists for Black males in the US. They inform about the quality of life that Black males are forced to live. Yet, they also serve to prevent other kinds of realizations about who these men are and what their capabilities happen to be. The statistics on health, employment, education, and family status easily imply that Black men have failed. Yet, other reports indicate how much society has failed them, in part because they appear to have fallen short in measures of social mobility and life satisfaction. In fact, most recently, the crisis of Black men has been made evident in public debate about whether they should be permitted to live. A rash of killings of African American males at the hands of police officers and citizens claiming to act in defense of their communities has been in the purview of the public for several years (and, in full disclosure, African American women have been subjected to this condition as well). As far as Black males are concerned, the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, and others have been well reported in the press (an overview of such reporting is found in Young 2017). What has also been reported, and what purports to be more troubling for Black men that are alive, is how much the presumed character of these men has been taken to be a justifiable factor in their deaths (Young 2017).

According to news sources, following coverage of his death at the hands of George Zimmerman, questions abounded as to whether Trayvon Martin was a marijuana user and a petty criminal, and whether his presumed status as such should serve as validating the circumstances of his death (Alcindor 2012; Alvarez 2013; Robles 2012). The killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 was followed by discussion of whether he was uncontrollable and threatening to those he encountered immediately prior to his being left to die on a street in that St. Louis suburb (Alcindor et al. 2014; Tacopino 2014). Tamir Rice was killed by a police officer in Cleveland on November 22, 2014, while in possession of a toy gun. The public image associated with him on that day was that of a Black male who appeared to be primed to do harm, even though other African American children and adults occupied the very public park near where he was killed and were unfazed by a Black boy in possession of a toy gun (Fitzsimmons 2014). Finally, at the time of his death on April 19, 2015, Freddie Gray was a 25-year-old ex-offender who was shackled and placed without a seat belt in a Baltimore City police van. In some of the media coverage of this event and the subsequent trial of the police officers indicted for Gray's death, he was referred to as the son of an illiterate heroin addict (Husband 2015).

Media coverage of the public debate following the death of these and other African American males centered on whether they conducted themselves as proper and decent people, or whether they appeared to be threatening or dangerous immediately prior to their deaths. In some cases, attention was devoted to whether they were substance abusers or delinquents. Underlying the conversations from those who defended or otherwise validated the actions of those who killed them was the image of Black males as badly behaved and threatening to other Americans. In short, what they did, who they were, or how they appeared to be at the time of their deaths was evidence enough to justify their deaths, or at least provide credible evidence as to why they occurred. The acquittals of US police officers initially charged with or investigated for the killing of African American males who were unarmed were grounded in arguments that those men posed extreme threat to the police officers who responded as they did to them – even though these men were neither armed nor in the midst of verbally threatening the police at the time of these occurrences (Abbasi 2017; Bouie 2017; Thrasher 2017). It is not simply the deaths of these Black males, but how they were accounted for in discussion of their deaths, that points to an additional dimension of the crisis of Black males. That crisis is the devaluation of the Black male body.

The past three decades have been a time in which media and technology have been indispensable tools for the proliferation of negative images of Black men and masculinity. These tools have allowed audiences to absorb these images without being in close contact with or proximity to these men. The troubling portrait of African American males has been sustained by a barrage of negative images about them emanating from mainstream and social media (an overview of such portraits is provided in Opportunity Agenda 2012). In these media, Black men are seen as highly predisposed to violence rather than conscientious, and easily given to surrender and withdrawal from schools and job prospects rather than of the media investigating whether poor schools and lower-tier jobs in their communities can actually serve them well. Messages from these outlets reify the negative public sentiment about Black males as unlawful, threatening, or unworthy.

Of course, that some of the Black males have done terrible things to themselves as well as to other people cannot be dismissed or denied. Research on low-income African American males has provided ample evidence that those who have ventured into these activities are conscious of what they have done and the societal impact that it has had (Harding 2010; Sullivan 1989; Venkatesh 2000, 2006; Williams 1989; Young 2004). However, the depiction of these males as having the capacity to be self-reflective or conscientious is suppressed by the pervasiveness of the character assassination. More concerning is the fact that African American males who do nothing to contribute to the negative public portrait of them suffer the consequences of this pervasive public portrait as they are assumed to be as problematic as those who effectively contribute to it. As sociologist Devah Pager and others have shown in researching the attitudes of employers, Black men are presumed to be ex-offenders or unworthy candidates for jobs even if no record of such a status appears on their resumes (Pager 2007; Pager et al. 2009a, 2009b; Quillian and Pager 2001; Wacquant 2001, 2005, 2010). Consequently, these males continue to be susceptible to a negative public identity that they in no way have helped to create and sustain.

This being the case, there is much work to be done to reconstitute the character of African American males. That work extends far beyond any superficial or shortsighted mandate for them to desist from engaging in problematic behavior. It also necessarily extends beyond the challenge of remediating the conduct of the police and other authority agents as they too often function with impunity in regard to Black males.

The crisis regarding the health and well-being of Black males, therefore, pertains not only to their already precarious physical condition. It also has to do with the rationalization and justification of the nefarious treatment of their bodies. Indeed, the inability to live healthy lives is not all there is to the contemporary crisis for Black males. It also includes the inability to be accorded dignity in death. Consequently, a present-day condition of the crisis of Black males is that the literal assassination of the Black male body is now coupled with a thorough character assassination. That is, if Black men are not subjected to violence at the hands of law enforcement authorities or everyday citizens, they are subjected to persecution that limits their prospects even if they possess the necessary credentials or experience for what they desire to pursue. Such men are boxed in by a publicly accepted script that assigns them an unworthy status. The enforcement of this script is necessarily a project for others to confront and challenge, and this means that the public must radically turn to addressing its problem with Black males rather than solely focusing on their problems.