Personality structure as outlined here can be studied wherever people are participating in transactions with each other—at the dinner table, at school, at social gatherings and at work. However, it is investigated most conveniently in psychotherapy groups, where the information needed for verifying the diagnosis of each aspect of the personality is more readily available than in other situations.

A classic example of the distinction between ego states emerged during the treatment of a male psychiatric patient, who told the following anecdote:

An 8-year-old boy vacationing on a ranch in his cowboy suit helped the hired man to unsaddle his horse. When they were finished, the

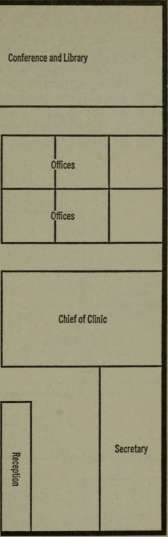

Fig. 21. A structural diagram.

132 Personality Structure

hired man said, "Thanks, cowpoke!" To which his assistant answered: "I'm not really a cowpoke; I'm just a little boy."

The man who told this story remarked: "That's just the way I feel. I'm not really a lawyer; I'm just a little boy." Away from the psychiatrist's office, he was an effective and successful courtroom lawyer of high repute. He reared his family decently, did a lot of community work and was popular socially. But in the psychiatrist's office he often did have the attitude of a little boy. Thus it was clear in his case that at certain times he behaved like a grown-up lawyer and at other times like a child. He became so familiar with these two different attitudes that sometimes during his treatment hour he would ask the therapist: "Are you talking to the lawyer or to the little boy?" It was soon possible to speak familiarly of these two attitudes as the Adult and the Child. It then appeared further that in his community work he was neither rational (Adult), as he was in the courtroom, nor lonely and apprehensive (Child) as he often was in the psychiatrist's office; rather he was inclined to feel emotionally involved with the downtrodden: sympathetic, philanthropic and helpful. And he recognized this as a duplication of his father's attitude; hence, it was doubly easy for him to accept the idea of calling this state of mind "parental."

His three states of mind, or ego states, were clearly distinguished in his ways of handling money. At times he would give away large sums, often to the detriment of himself and his family. At other times he would handle his finances with a banker's shrewd foresight. On still other occasions he would get into petty disputes or difficulties over a few pennies. As noted, he recognized the philanthropic attitude as resembling that of his father. In the second condition he was shrewdly appraising the information offered by the environment. In the third condition he recognized relics of the way he had behaved about money when he was a little boy. The clear distinction between the three ego states was brought out by the conflicts that each of these forms of behavior aroused. When he was philanthropic, the lawyer in him would rebel against the unwise use of his funds, and the childlike part of him would resent the fact that he had to give away money that he might use for his own pleasure. In structural language, both his Adult and his Child objected to his Parental way of handling money. When he was being shrewd, his Parent would reproach him with being inconsiderate of other people's needs, while his Child would regard his financial manipulations with a kind of awe. When his Child was being petty, his Parent would express disapproval and his Adult, the lawyer, would caution him that he might get into a great deal of trouble over a triviality, such as cheating a shopkeeper out

of a few pennies. Sometimes these various protests would take the form of ill-defined feelings, but at other times they would take well-verbalised forms so that he would engage in a triologue with himself.

From this brief description it can already be seen that it was possible to analyze in structural terms any of his financial operations, whether it was donating a large sum to the Community Chest, buying securities or stealing chewing gum from a grocery store. In each case it was possible to say which of the three aspects of his personality was executing the transaction. This type of analysis, in which the executive ego state involved in any transaction is diagnosed, is called structural analysis.

For a clear understanding of what an individual is up to in a group, accurate structural analysis is necessary. However, this should not rest merely on the opinion of the observer, and unless the diagnosis is thoroughly verified, it should always be regarded as tentative. The diagnosis is complete when it can be supported from four different viewpoints.

1. The diagnosis made by the observer is behavioral. For example, a behavioral diagnosis can be made if someone unpredictably and somewhat inappropriately bursts into tears, so that the observer is irresistably reminded of the behavior of a child at a certain age; or if the agent exhibits coyness, sulkiness or playfulness which is reminiscent of a special phase of childhood.

2. Those participating in transactions with the agent make the diagnosis on social grounds. If he behaves in such a way as to make them feel fatherly or motherly, he is presumably offering childlike stimuli, and his behavior at that moment can be diagnosed as a manifestation of his Child. Conversely, the respondents' behavior can be diagnosed as Parental. If the agent elicits objective responses related to the outside environment, then the respondents are in the Adult ego state, and the chances are that the agent is also in this ego state. Conversely, if two people are building a boat and one says (Adult): "Pass me the hammer," the respondent's reply will reveal his ego state. If he says: "Always be careful to keep your fingers out of the way when you're hammering," this response may be presumed to come from his Parent. If he says: "Which hammer?" his response may be assumed to come from his Adult. If he says petulantly: "Why do I have to do everything around here?" his complaint may be diagnosed as coming from his Child.

3. The subjective diagnosis comes from self-observation. The individual himself realises that he is acting the way his father did, or that he is objectively interested in what is going on before him, or that he is reacting the way he did as a child.

134 Personality Structure

4. The historical diagnosis is made from factual information about the individual's past. He may remember the exact moments when his father behaved in a similar way; or where he learned how to accomplish this particular task; or exactly where he was when he had a similar reaction in early childhood.

The more of these standards that can be met, the sounder the diagnosis is. The full psychiatric diagnosis of an ego state requires that the observer, the individual's associates, his self-observation and his personal history all point in the same direction.

Since in most situations the social, the subjective and the historical diagnosis cannot be obtained, the behavioral diagnosis is the most important to the general student of groups. For example, a PTA meeting cannot be interrupted to ask whether everyone agrees that a certain member made them feel like children when he spoke; or whether the member felt Parental when he said what he did; or whether his father often spoke in the same tone, and if so, under what circumstances he did it. Therefore, behavioral observations are particularly valuable to collect. A few selected items will illustrate the point.

1. Demeanor. The sternly paternal uprightness, sometimes with extended finger, and the gracious mothering flexion of the neck soon become familiar as Parental attitudes. Thoughtful concentration, often with pursed lips or slightly flared nostrils, are typically Adult. The inclination of the head which signifies coyness, or the accompanying smile which turns it into cuteness, are manifestations of the Child. So is the aversion and fixed brow of sulkiness, which can be transformed into reluctant and chagrined laughter by Parental teasing. Observations of family life will reveal other characteristic attitudes belonging to each type of ego state: parents being Parental, students being Adult, and children being Childlike. An interesting exercise is to go through the text and especially the illustrations of Darwin's book on emotional expression, with structural analysis in mind.

2. Gestures. The Parental origin of forbidding and refusing gestures is often obvious if the observer is acquainted with the agent's family. Certain kinds of pointing with the index finger come from the Adult: a professional man talking to a colleague or client, a foreman instructing a workman, or a teacher assisting a pupil. A warding off gesture of the arm, when it is out of place, is a manifestation of the Child. Some gestures are easily diagnosed by intuition. For example, sometimes it is easy to see that pointing with the index finger is not Adult but is part of an exhortation by the Parent or of a plaintive accusation by the Child.

3. Voice. It is quite common for people to have two voices, each with a different intonation, although in many situations one or the other may be suppressed for very long periods. For example, one who presents herself in a therapy group as "little old me" may not reveal for many months the hidden voice of Parental wrath (perhaps that of an alcoholic mother); or it may require intense group stress before the voice of the "judicious workman" collapses, to be replaced by that of his frightened Child. Meanwhile, intimate friends and relations may be fully aware of both intonations. Nor is it exceedingly rare to meet people who have three different intonations: under favorable circumstances one may literally encounter the voice of the Parent, the voice of the Adult and the voice of the Child all coming from the same individual. When the voice changes, it is usually not difficult to detect other evidences of the change in ego state. One of the most dramatic illustrations is when "little old me" is suddenly replaced by the facsimile of her infuriated mother or grandmother.

4. Vocabulary. Certain words and phrases are characteristic of particular ego states. An important example is the distinction between "childish," which is invariably a Parental word, and "childlike," which is Adult. "Childish" means "not acceptable" while "childlike," properly used, is an objective biologic term.

Typical Parental words are: cute, sonny, naughty, low, vulgar, disgusting, ridiculous, and many of their synonyms. Adult words are: unconstructive, apt, parsimonious, desirable. Oaths, exclamations and name-calling are often manifestations of the Child. Nouns and verbs are in themselves Adult, since they refer without prejudice, distortion or exaggeration to objective reality, but they may be employed for their own purposes by Parent or Child. Diagnosis of the word "good" is an intriguing exercise in intuition. With a recognized or unrecognized capital G it is Parental. When its use is strictly rational and defensible, it is Adult. When it means instinctual gratification, and is really an exclamation, it comes from the Child, being then an educated synonym for something like "Yum yum!" or "Mmmmm!" Very commonly, it expresses Parental prejudices which are faked out as Adult: it is said as if it had a small g, but if it is questioned, the capital G begins to show through. The speaker may become angry, defensive or anxious at the questioning, or at best the evidence he brings up to support his opinion is flimsy and poorly thought out.

These examples merely illustrate some of the possibilities. There is a very large number of behavior patterns available to the human being. Anthropologists have compiled long lists of deportments, and specialists (pasimologists) estimate that some 700,000 distinct ele-

136 Personality Structure

mentary gestures can be produced by different muscular combinations. There are enough variations in timbre, pitch, intensity and range of vocalization to occupy the attention of whole schools of students and teachers. The problems of vocabulary are so complex that they are divided between different disciplines. And these are only four categories out of the almost innumerable types of indicators available to the structural analyst. The only practical course for the serious student is observation: to observe parents acting in their capacity as parents; adults acting in their capacity as thoughtful and responsible citizens; and children acting like children at the breast, in the cradle, in the nursery, the bathroom and the kitchen, and in the schoolroom and the play-yard. By cultivating his powers of observation and intuition, he can add new dimensions of interest to his work.

Mr. Mead's presentation of three ego states to Group S has already been noted. When he gave his preliminary discussion, he was in an Adult ego state, talking objectively about the problems of the spiritualist medium and about what the members were going to become involved in. Ruby exhibited a typical childlike ego state. Dr. Murgatroyd at first presented an authoritative Parental ego state; later, during the experiments, he switched into that of a hurt child.

SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS

The special characteristics of each type of ego state will now be reviewed in more detail. This will help in understanding further the relationships between the individual member and the other people in a group.

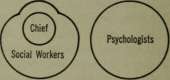

A. A Parental ego state is a set of feelings, attitudes and behavior patterns that resemble those of a parental figure. The diagnosis is usually made first by observation of demeanor, gestures, voice, vocabulary and other characteristics. This is the behavioral diagnosis. It is supported if the particular set of patterns is especially apt to be aroused by childlike behavior on the part of someone else in the group. This is the social diagnosis. In psychotherapy groups, the diagnosis may be further investigated through the family history and the individual's reports of his own feelings—the historical and the subjective diagnoses. The Parent usually shows in one of two forms: prejudiced or nurturing. The prejudiced Parent has a dogmatic and disapproving attitude. If the prejudices happen to be the same as those of other people in the group, they may be accepted as rational, or at least justifiable, without adequate examination. The nurturing Parent is often Bhown in "supporting" and sympathizing with another individual.

The Parental ego state must be distinguished from the Parental

influence. The Parental ego state means "Your Parent is talking now; you are talking like your mother." The Parental influence means "Your Child is talking that way to please your Parent; you are talking as mother would have liked you to."

The value of the Parent is that it saves energy and lessens anxiety by making certain decisions "automatic" and not to be questioned.

B. The Adult ego state is an independent set of feelings, attitudes and behavior patterns that are adapted to the current reality and are not affected by Parental prejudices or archaic attitudes left over from childhood. In each individual case, due allowances must be made for past learning opportunities. The Adult of a very young person or of a peasant may make very different judgments from that of a professionally trained worker. The question is not the accuracy of the judgments, nor their acceptability to the other members (which depends on their Parental prejudices) but on the quality of the thinking and the use made of the resources available to that particular person. The Adult is the ego state which makes survival possible.

C. The Child ego state is a set of feelings, attitudes and behavior patterns that are relics of the individual's own childhood. Again, the behavioral diagnosis is usually made first by careful observation. If that particular set of patterns is most likely to be provoked by someone who behaves parentally, that gives the social diagnosis. The historical diagnosis comes from memories of similar feelings and behavior in early childhood. The subjective diagnosis, the actual reliving of the original childhood experience, should only be attempted in the course of psychotherapy under the guidance of a fully qualified therapist.

The Child comes out in one of two forms: adapted or natural. The adapted Child acts under the Parental influence and has modified its natural way of expression by compliance or avoidance. The natural Child is freer, more impulsive and self-indulgent. The Child is in many ways the most valuable aspect of the personality, and if it can find healthy ways of self-expression and enjoyment, it may make the greatest contribution to vitality and happiness.

SUMMARY

The most significant hypotheses offered in this chapter are as follows:

1. The behavior of any individual in a group at any given moment can be classified into one of three categories, colloquially called Parent, Adult and Child.

2. Behavioral, social, historical and phenomenologic data converge to validate such classifications.

138 Personality Structure

3. Parent, Adult and Child, on the basis of clinical evidence, are treated primarily as states of mind, or ego states, and it is proposed that such organizations arise from one of three psychic organs: exteropsyche, neopsyche and archaeopsyche, respectively.

4. Accurate structural analysis is necessary (or at least desirable) for precise understanding of the behavior and the function of each individual in a group.

SPECIAL TERMS INTRODUCED IN THIS CHAPTER

Transaction Parent

Agent Adult

Transactional stimulus Child

Respondent Structural analysis

Transactional response Behavioral diagnosis

Social aggregation Social diagnosis

Dissocial aggregation Subjective diagnosis

Social psychiatry Historical diagnosis

Social dynamics Prejudiced Parent

Transactional analysis Nurturing Parent

Ego state Parental ego state

Exteropsyche Parental influence

Neopsyche Adapted Child

Archaeopsyche Natural Child

TECHNICAL NOTES

The word "dissocial" is preferred to "unsocial" for describing non-transacting aggregations because "unsocial" has an unfair implication of sulkiness.

The case of the philanthropic lawyer has been presented in more detail in several of the writer's publications (e.g., "Ego States in Psychotherapy," American Journal of Psychotherapy i2;293-309, 1957). It should be emphasized that Parent, Adult and Child are not neologisms or synonyms for Superego, Ego and Id. The former are ego states, the latter are concepts. This question is discussed at more length in my book on Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy (New York, Grove Press, 1961). The exposition given in the present chapter is in effect an attempt to summarize pertinently the contents of the first part of that book, which should be read by anyone who desires more information about the physiologic and psychological bases of structural analysis, or who is critical of the formulations as presented here.

E. T. Hall offers an excellent account of the anthropologic study of deportment (The anthropology of manners, Scientific American 192:84-90, April 1955), while the linguist Mario Pei discusses pasimology (The Story of Language, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1949).

w

j4K*l(f4i4, oj *7*«AttoictiaK&

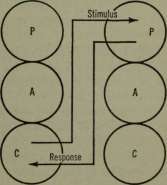

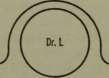

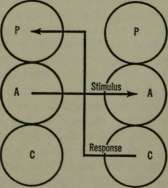

SIMPLE COMPLEMENTARY TRANSACTIONS

The object of transactional analysis is to diagnose which ego states give rise to the transactional stimulus and the transactional response in any transaction that is being investigated. Anyone who proposes to deal with ailing groups should become familiar with this procedure. A simple transaction is represented by drawing two structural diagrams side by side, one for the agent and one for the respondent, as in Figures 22 and 23. An arrow is then drawn from the active ego state of the agent to whichever aspect of the respondent he is addressing. This represents the transactional stimulus. Another arrow is drawn similarly from the respondent to the agent to represent the transactional response. Such a diagram is called a transactional diagram, and the two arrows are called vectors.

In order for the group work in all its aspects to proceed without turbulence, communication between members must progress smoothly.

Stimulus

Response

A. Type I B. Type II

Fig. 22. Complementary transactions.

140 Analysis of Transactions

A. Type I

B. Type

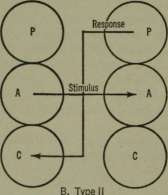

Fig. 23. Crossed transactions.

C. Type III

This will occur as long as transactions are complementary. A complementary transaction is one in which the two vectors are parallel. Most commonly, such transactions are Adult-to-Adult, or between Parent and Child.

The complementary Adult-to-Adult transaction typically occurs in the course of the group activity. In everyday life it is exemplified by the question "What time is it?" and the response "Three-thirty." This Adult-to-Adult stimulus evoking Adult-to-Adult response may be classified as Complementary Transaction Type I and is represented in Figure 22A.

The second type of common complementary transaction—that taking place between Parent and Child—is easily observed in family life

where actual children ask actual parents for help, reassurance or protection. Corresponding transactions occur between grownups when one of them is in difficulties and needs a helpful, reassuring or protective type of response. For example, a feverish husband, who learned how to be sick when he was a little boy, reverts to a Child ego state and goes to bed. His wife, who learned how to take care of sick people from her mother, shifts into a Parental ego state and takes care of him. If she falls sick, their roles will be switched, and so will their ego states. Such mutual loving care in time of need is an example of Complementary Transaction Type II and is represented in Figure 22B. The Adult ego state is particularly vulnerable to certain drugs and bacterial toxins. Usually anyone with a high fever will be unable to maintain his Adult and will revert to a Child ego state, thus activating the nurturing Parent in those concerned with his welfare. They will then go beyond the strictly Adult medical requirements of treatment to comfort and reassure him.

CROSSED TRANSACTIONS

Returning now to the Adult agent who wanted to know the time, suppose the respondent, instead of telling him, answers differently. Suppose he says like a sulky child "Why do I have to keep track of the time?" or alternatively, in the tone of a reprimanding parent, "If you had your own watch, you'd be more punctual!" In either case, the agent becomes disconcerted. The respondent has raised new questions which are no longer concerned directly with the time of day. Communication is broken off on that subject and has to be re-established in a different direction. The agent at this point is likely to be distracted by resentment or self-defense. The first example, in which an Adult-to-Adult stimulus ("What time is it?") finds a sulky Child-to-Parent response, is illustrated in Figure 23A, and is called Crossed Transaction Type I. The second example, in which Adult-to-Adult stimulus gets a reprimanding Parent-to-Child response, is illustrated in Figure 23B and is called Crossed Transaction Type II. The important thing to notice about these two transactional diagrams is that the vectors are not parallel, as in a complementary transaction, but cross each other. This gives rise to one of the most important rules in the therapy of ailing groups, the rule of communication: communication is broken off when a crossed transaction occurs. This can also be put the other way round: if communication is broken off, there has been a crossed transaction.

A study of a simple transactional diagram makes it evident that there are 9 possible types of complementary transactions, including Adult-to-ChHd and Child-to-Adult, Parent-to-Parent and so forth,

142 Analysis of Transactions

but most of these occur only rarely in comparison with Types I and II. There are a larger number of possible crossed transactions, but, again, most of them are rare in comparison with Types I, II and III illustrated in Figure 23. Since the diagrams are not (topologically) perfect, some of the crossed transactions when drawn will not show an actual cross. Therefore, strictly speaking, a crossed transaction is better defined as one in which the vectors are not parallel. But in the commonest cases, the cross will show clearly.

The detection of crossed transactions is of great practical importance. For example, Crossed Transaction Type I (Fig. 23A) gives rise and has always given rise to most of the difficulties in the world —historical, marital, occupational and otherwise. If this type of transaction is found to be frequent in any relationship, it can be predicted that the relationship will go badly and will probably end in a misunderstanding or rupture. Many of the problems of psychiatry and group therapy can be studied from this point of view. Crossed Transaction Type I is the major concern of psychoanalysis and constitutes the typical "transference reaction." For example, if the (Adult) analyst says something like: "Your behavior reminds me of the way you behaved during the incident which occurred when you were 3 years old," in a sense he is entitled to expect a response like: "That's worth thinking about!" This would indicate that the patient's Adult is interested in the declared purpose of the treatment, which is to obtain increased understanding of himself. A transference reaction would go something like: "You're always criticising me!," clearly a Child-to-Parent response. The "counter-transference reaction," to which more and more attention is being devoted, is typified by Crossed Transactions Types I (Fig. 23A) and II (Fig. 23B), in which the patient makes an objective (Adult) statement and the analyst becomes either irritated in a childlike way or pompously Parental.

INDIRECT TRANSACTIONS It can be observed in many groups that something is said by A to B which is intended to influence C indirectly. This timid approach is often thought of as tact or diplomacy. Such transactions commonly occur in so-called "well-run" groups, in which questionable methods of influencing people are considered to be good form. For example, instead of facing the boss directly, a suggestion may be made in his hearing to someone else in the hope that it will influence the boss. Since such devices are evidence of a poor relationship between the agent and the boss and originate from fear or insecurity, the question of whether this is really good practice may be raised. It will be noted that indirect transactions are really three-handed transactions in

which the respondent is used as a kind of go-between in transacting psychological business with a third party.

DILUTED TRANSACTIONS

In the course of any group activity, no matter how businesslike, nearly everybody becomes personally involved to some extent sooner or later. In this country, a common approach to this is for workers to kid each other. Here certain transactions which are half-hostile, half-affectionate, take place through the material of the activity. A may ask B to pass the hammer and say it in a kidding way ("Hey, squarehead, where's the hammer?"), and B may throw the hammer instead of passing it, which is a kind of retaliative kidding or testing of A. Such transactions which are embedded in the material of the group activity may be called diluted transactions.

A direct transaction is one which is neither indirect or diluted. The evidence is that even if "playing it smart" by the use of indirect or diluted transactions may lead to a certain kind of material success, the more admirable members of the human race tend to use direct transactions in important situations.

INTENSITY

Transactional analysis deals with what actually happens rather than with what is going on in the minds of the individuals concerned. Someone who uses indirect or diluted transactions may be motivated by very intense feelings, but the feelings are deflected or watered down in the actual transactional exchanges. When the transaction itself can be observed or judged to have a strong emotional intensity at the time of its occurrence, it is more likely to be direct than indirect or diluted. It is often useful to classify transactions according to their intensity. The most intense are passionate murder or impregnation, the one the most intense expression of hostility, the other the most intense expression of love. If murder takes the form of accidental manslaughter, or impregnation takes place in the course of more or less perfunctory love-making, then the transaction as carried out may not have been very intense. Similarly, the transactions which are more open to everyday observation should be carefully considered before their intensity is estimated.

The important items to be considered in analyzing single, simple transactions are therefore complementarity (or crossing), directness (or indirectness), purity (or dilution) and intensity (or weakness). Thus in intimate love relationships, people talk to each other relevantly, directly, without distractions, and intensely.

144 Analysis of Transactions

ULTERIOR TRANSACTIONS

Simple transactions are those that can be regarded as involving only a single ego state in each of the people concerned. However, a large number of transactions are obviously based on ulterior motives. An ulterior transaction is one that involves major activity from more than one ego state in one or all of the individuals concerned.

In certain situations ulterior transactions are deliberately cultivated, and their properties are carefully studied, although not under that name. For example, an insurance salesman who takes an authoritative, paternal interest in the welfare and the future of a potential client is engaging in an ulterior transaction, since, however genuine his Parental interest in the client, his chief goal is the Adult one of getting money from him. Good salesmanship, advertising and promotion always involve ulterior transactions in which a real or apparent concern with the welfare of the prospective buyer conceals quite another interest. The fact that salesmen speak of "making a killing," and are not referring entirely to their own financial gain but to a kind of childlike victory over the client, shows that in most cases the Child of a salesman is involved in his work, as well as his carefully cultivated Parental attitude and his Adult skill in closing sales. This ulterior aspect is more or less frankly acknowledged in referring to "the insurance game," "the real estate game" and, among criminals, to "the con game." Some ulterior transactions, such as cultivating acquaintances at parties with the ulterior motive of selling them something later, or playing golf with the ulterior object of exploiting the relationship later, are socially acceptable in many circles. Such operations must conform to the etiquette of informal commerce. Expert sales work requires social and psychological sophistication in order to appeal to more than one ego state of the client.

Diagrams of some ulterior transactions will be found in the next chapter.

SUMMARY

The following hypotheses are proposed:

1. Simple transactions can be usefully and pertinently classified according to certain significant variables: complementarity, directness, purity and intensity.

2. As long as transactions are complementary, communication can be maintained indefinitely. It is broken off if a crossed transaction occurs and must be re-established at a new level.

SPECIAL TERMS INTRODUCED IN THIS CHAPTER

Transactional diagram Direct transaction

Vector Intensity

Complementary transaction Purity

Crossed transaction Simple transaction

Indirect transaction Ulterior transaction Diluted transaction

TECHNICAL NOTES

For further information regarding the analysis of transactions, my book on this subject (Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy, loc. cit.) or, for a shorter account, the paper on this subject cited previously (American Journal of Psychotherapy 22:735-743, 1958) may be consulted.

/^W^4& o£ (fane*

INDIVIDUAL PARTICIPATION

The analysis of single transactions may be very useful in certain situations, but for a more thorough understanding of the nature of the individual's participation in the proceedings of a group, it is necessary to consider chains of transactions. Such chains can be usefully classified into six important types, including the extreme cases of nonparticipation (withdrawal) and "total" participation (intimacy). This gives the individual six options or choices as to how he will conduct himself in a group.

1. Withdrawal. Some people may be physically present but are in effect mentally absent from the gathering. They do not participate in the proceedings, and on inquiry it is found that they are engaged in fantasies. These generally fall into one of two classes:

a. Extraneous fantasies in which the individual mentally leaves the group and imagines himself elsewhere doing something quite unrelated to the proceedings.

b. Autistic transactions in which he is interested in what is going on but for various reasons is unable to participate. He spends his time imagining things that he might say or do with various members of the group. Autistic transactions are sometimes concerned with the possibility of participating in an acceptable way and at other times are less well adapted to the situation and may be concerned with direct assaults or sexual advances which would be quite unacceptable to the other members. Thus, autistic transactions may in turn be classified as adapted or unadapted.

2. Rituals, ceremonies and ceremonials. The preliminary and closing stages of the proceedings of any social aggregation, including groups, are often ritualistic in nature. These ritualistic phases may be abortive, consisting only of standard greetings and farewells, or they may be more prolonged, with formalities such as reading the minutes and votes of thanks. At formal ceremonies, such as weddings, not only the initial and terminal phases, but also the body of the meeting

is ritualistic. From the point of view of social dynamics, the characteristic of ritualistic behavior is predictability. If at the beginning of a meeting one member says to another "Hello," it can be predicted with a high degree of confidence that the response will be "Hello" or one of its equivalents. If the first member then says "Hot enough for you?" it can likewise be predicted that the response will be "Yes," or some variant—similarly with the farewells at the end of a meeting. In a traditional ritual such as a church service, the stimuli and the responses are well known to all present and are completely predictable under ordinary conditions.

The unit of ritualistic transactions is called a stroke. The following is an example of a typical 8-stroke American greeting ritual:

A. "Hi!"

B. "Hi!"

A. "Warm enough for you?"

B. "Sure is. How's it going?"

A. "Fine. And you?"

B. "Fine."

A. "Well, so long."

B. "I'll be seeing you. So long."

Here there is an approximately equal exchange comprising a greeting stroke, an impersonal stroke, a personal stroke and a terminal stroke. Such rituals are part of the group etiquette.

At a group meeting the first six strokes may be exchanged at the beginning and the last two at the end. The problem then remains how the time is filled in between these two segments.

3. Activity. Most groups come together for the ostensible purpose of engaging in some activity which, as noted, is usually mentioned at least in a general way in the constitution. Pure activity in transactional language consists of simple, complementary, Adult transactions starting with something like "Pass the hammer!" or "What is the sum of 3 plus 3?" If there is no planned activity, as at many social parties, and in some psychotherapy groups, then the time is usually filled in with either pastimes or games.

4. Pastimes. Pastimes consist of a semi-ritualistic series of complementary transactions, usually of an agreeable nature and sometimes instructive. At formal meetings the time between the greeting rituals and the beginning of the formal proceedings is often filled in with pastimes. During this period the gathering has the structure of a party rather than that of a group. At social parties, pastimes may occupy the whole period between the greeting and the terminal rituals. In psychotherapy groups, they may continue or be initiated even

148 Analysis of Games

after the entrance of the therapist which signals the beginning of the formal proceedings.

5. Games. As members become acquainted with each other, generally through pastimes carried on in the course of the group activity, they tend to develop more personal relationships with each other, and ulterior transactions begin to creep in. These often occur in chains, with a well-defined goal, and are actually attempts of various people to manipulate each other in a subtle way in order to produce certain desired responses. Such sets of ongoing transactions with an ulterior motive are called games.

6. Intimacy comes out transactionally in the direct expression of meaningful emotions between two individuals, without ulterior motives or reservations. Under special conditions, as in family life, more than two people may be engaged. Since such "pairing" may distract from the activity of a group, it is not encouraged in large work groups. For example, some organizations have a rule that if two members marry, one of them must resign. Because the subjective aspects are so important in true intimacy, and because it rarely comes out in groups because of external prohibitions and internal inhibitions, its characteristics are difficult to investigate. Indeed, this is one of the cases in which attempts at investigation are likely to destroy what is being investigated, since true intimacy is by nature a private matter. Few people would care to have their honeymoons tape recorded by a third person. There are certain sacrifices that should not be expected, even for the sake of science.

Pseudo-intimacy (with ulterior motives or reservations) is quite another matter and is frequently observed and erroneously described in the scientific literature as real intimacy. Some special groups are set up so that physical freedom, including sexual intercourse, is encouraged, but these are ritualistic, commercialized or rebellious and do not necessarily promote the subjective binding of two personalities. Pseudo-intimacy usually falls into the category of rituals, pastimes or games.

These six options have been listed roughly in order of the complexity of engagement and the seriousness of the commitment. The two extremes, withdrawal and intimacy, properly belong to the field of psychiatry. The two that stand out as most needful of further clarification for the student of social dynamics are pastimes and games, since these are the ones that most commonly affect the course of the internal group process.

PASTIMES A pastime may be described as a chain of simple complementary

transactions, usually dealing with the environment and basically irrelevant to the group activity. Pastimes are appropriate at parties, and they can be easily observed in such unstructured enclaves. Happy or well-organized people whose capacity for enjoyment is unimpaired may indulge in a social pastime for its own sake and for the satisfactions which it brings. Others, particularly neurotics, engaged in pastimes for just what their name implies—a way of passing (i.e., structuring) the time "until": until one gets to know people better, until this hour has been sweated out, and on a larger scale, until bedtime, until vacation-time, until school starts, until the cure is forthcoming, or until a miracle, rescue or death arrives. (In therapy groups the last three are known colloquially as "waiting for Santa Claus".) Besides the immediate advantages which it offers, a pastime serves as a means of getting acquainted in the hope of achieving the longed-for intimacy with another human being. In any case, each participant tries to get whatever he can out of it. The best place to study pastimes systematically is in psychotherapy groups.

The two commonest pastimes in such groups are variations of "PTA" and "Psychiatry," and these may be used as illustrations for analysis. At an actual Parent-Teachers Association meeting "PTA," officially at least, is not a pastime, since it is the constitutionally stated activity of the group. But in a psychotherapy group it is basically irrelevant because very few people are cured of neuroses or psychoses by playing it. In that situation it occurs in two forms. The projective type of "PTA" is a Parental pastime. Its subject is delinquency in the general meaning of the word, and it may deal with delinquent juveniles, delinquent husbands, delinquent wives, delinquent tradesmen, delinquent authorities or delinquent celebrities. Introjective "PTA" is Adult and deals with one's own socially acceptable delinquencies. "Why can't I be a good mother, father, employer, worker, fellow, hostess?" The motto of the projective form is "Isn't It Awful?"; that of the introjective form is "Me Too!"

"Psychiatry" is an Adult or at least pseudo-Adult pastime. In its projective form it is known colloquially as "Here's What You're Doing"; its introjective form is called "Why Do I Do This?"

People in therapy groups are particularly apt to fall back on pastimes in three types of situations: when a new member comes in, when the members are avoiding something, or when the leader is absent. The superficial nature of these interchanges is shown in the following two examples, the analyses of which are represented in Figures 24 and 25.

150 Analysis of Games

I. "PTA"—projective type.

Mary: "There wouldn't be all this delinquency if it weren't for broken homes."

Jane: "It's not only that. Even in good homes nowadays the children aren't taught manners the way they used to be."

II. "Psychiatry"—introjective type.

Mary: "Painting must symbolize smearing to me." Jane: "In my case, it would be trying to please my father." In most cases pastimes are variations of "small talk," such as "General Motors" (comparing cars) and "Who Won" (both "man-talk"); "Grocery," "Kitchen" and "Wardrobe," (all "lady talk"); "How To" (go about doing something), "How Much" (does it cost?), "Ever Been" (to some nostalgic place), "Do You Know" (so-and-so), "Whatever Became" (of good old Joe), "Morning After" (what a hangover), and "Martini" (I know a better drink).

It is evident that at any given moment when two people are engaged in one of these pastimes, there are thousands of conversations going on throughout the world, allowing for differences in time zones, in which essentially the same exchanges are taking place, with a few differences in proper nouns and other local terms. The situation brings to mind those printed postal cards which were supplied to the soldiers in the trenches in World War I, in which the terms that did not apply could be crossed out; or those box-top contests that require the completion of a sentence in less than 25 words. Thus, pastimes are for the most part stereotyped sets of transactions, each

Stimulus

Response

Stimulus

Response

Mary Jane Mary Jane

Fig. 24. "PTA"—projective type. Fig. 25. "Psychiatry"—introjective

type.

PASTIMES

element consisting of what a psychology student might call a multiple choice plus a sentence completion; e.g., in "General Motors": "I like a (Ford, Plymouth, Chevrolet) better than a (Ford, Plymouth, Chevrolet) because . . ."

The social value of pastimes is that they offer a harmless way for people to feel each other out. They provide a preliminary period of noncomittal observation during which the players can line each other up before the games begin. Many people are grateful for such a trial period, because once he is committed to a game, the individual must take the consequences.

GAMES

The game called "If It Weren't For You," which is the commonest game played between husbands and wives, can be used to illustrate the characteristics of games in general.

Mrs. White complained that her husband would not allow her to indulge in any athletic or social activities. As she improved with psychiatric treatment, she became more independent and decided to do some of the things she had always wanted to do. She signed up for swimming and dancing lessons. When the courses began, she was surprised and dismayed to discover that she had abnormal fears of both swimming pools and dance-floors and had to give up both projects.

These experiences revealed some important aspects of the structure of her marriage. There were good Parental and Adult reasons why she loved her husband, but her Child had a special interest in his domineering Parent. By prohibiting outside activities, he saved her from exposing herself to situations that would frighten her. This was the psychological advantage of her marriage. At the same time, as a kind of bonus, he gave her the "justifiable" right to complain about his restrictions. These complaints were part of the social advantages of the marriage. Within the family group, she could say to him: "If it weren't for you, I could . . . etc." Outside the home, she was also in an advantageous position, since she could join her friends, with a sense of gratification and accomplishment, in their similar complaints about their husbands: "If it weren't for him, I could . . . etc."

"If It Weren't For You" was a game because it exploited her husband unfairly. In prohibiting outside activities, Mr. White was only doing what his wife's Child really wanted him to do (the psychological advantage), but instead of expressing appreciation, she took further advantage of him by enjoying herself in complaining about it (the social advantage).

But it was an even exchange, and that is what kept the marriage

152 Analysis of Games

going; for Mr. White, on his side, was also using the situation to get questionable satisfactions out of it. As an important by-product, the White children's emotional education included an intensive field course in playing this game, so that eventually the whole family could and did indulge in this occupation skillfully and frequently. Thus, the social dynamics of this family revolved around the game of "If It Weren't For You."

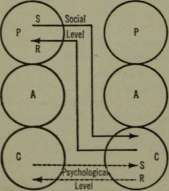

In a pastime the transactions are simple and complementary. In a game they are also complementary, but they are not simple; they involve two levels simultaneously, called the social and the psychological. The transactional analysis of "If It Weren't For You" is shown in Figure 26. At the social level, the scheme is as follows:

Husband: "You stay home and take care of the house."

Wife: "If it weren't for you I could be having fun."

Here the transactional stimulus is Parent to Child, and the response is Child to Parent.

At the psychological level (the ulterior marriage contract) the situation is quite different.

Husband: "You must always be here when I get home. I am terrified of desertion."

Wife: "I will be, if you help me to avoid situations that arouse my abnormal fears."

Here both stimulus and response are Child to Child. At neither level is there a crossing, so that the game can proceed indefinitely as

Husband Wife

Fig. 26. "If It Weren't For You."

Hyacinth Others

Fig. 27. "Why Don't You . . Yes, But."

GAMES

long as both parties are interested. Such a transaction, since it involves two complementary levels simultaneously, is a typical ulterior transaction.

A game can be defined as a set of ongoing ulterior transactions with a concealed motivation, leading to a well-defined climax. Because each player has a definite goal (of which he may not be aware), the innocent-looking transactions are really a series of moves with a snare or "gimmick" designed to bring about the climax or "pay-off." The most common game in parties and groups of all kinds including psychotherapy groups, is "Why Don't You . . . Yes, But." Hyacinth: "My husband never builds anything right." Camellia: "Why doesn't he take a course in carpentry?" Hyacinth: "Yes, but he doesn't have time." Rosita: "Why don't you buy him some good tools?" Hyacinth: "Yes, but he doesn't know how to use them." Holly: "Why don't you have your building done by a carpenter?" Hyacinth: "Yes, but that would cost too much." Iris: "Why don't you just accept what he does the way he does it?" Hyacinth: "Yes, but the whole thing might fall down." "Why Don't You . . . Yes, But" can be played by any number. One player, who is "It," presents a problem. The others start to present solutions, each beginning with "Why don't you?" To each of these the one who is "It" objects with a "Yes, but ..." A good player can stand off the rest of the group indefinitely, until they all give up, whereupon "It" wins. Hyacinth, for example, successfully objected to more than a dozen solutions before Rosita and the therapist broke up the game.

Since all the solutions, with rare exceptions, are rejected, it soon becomes evident that this game must serve some ulterior purpose. The "gimmick" in "Why Don't You . . . Yes, But" is that it is not played for its apparent purpose (an Adult quest for information or solutions) but to reassure and gratify the Child. In writing it may sound Adult, but in the living tissue it can be observed that the one who is "It" presents herself as a Child inadequate to meet the situation; whereupon the others become transformed into sage Parents anxious to dispense their wisdom for the benefit of the helpless one. This is exactly what "It" wants, since her object is to confound these Parents one after another. The analysis of that game is shown in Figure 27. The game can proceed because, at the social level, both stimulus and response are Adult to Adult, and at the psychological level they are also complementary, a Parent-to-Child stimulus ("Why don't you . . .") bringing out a Child-to-Parent response ("Yes, but .. ."). The psychological level may be unconscious on both sides.

154 Analysis of Games

Some interesting features come to light by following through on Hyacinth's game.

Hyacinth: "Yes, but the whole thing might fall down."

Dr. Q: "What do you all think of this?"

Rosita: "There we go, playing 'Why Don't You . . . Yes, But' again. You'd think we'd know better by this time."

Dr. Q: "Did anyone suggest anything you hadn't thought of yourself?"

Hyacinth: "No, they didn't. As a matter of fact, I've actually tried almost everything they suggested. I did buy my husband some tools, and he did take a course in carpentry."

Dr. Q: "It's interesting that Hyacinth said he didn't have time to take the course."

Hyacinth: "Well, while we were talking I didn't realize what we were doing, but now I see I was playing 'Why Don't You . . . Yes, But' again, so I guess I'm still trying to prove that no Parent can tell me anything, and this time I even had to lie to do it."

One object of games it to prevent discomfort by structuring an interval of time. This was clearly brought out by another woman, Mrs. Black. As is commonly the case, Mrs. Black could switch roles in any of her favorite games. In "Why Don't You . . . Yes, But," she was equally adept at playing either "It" or one of the sages, and this was discussed with her at an individual session.

Dr. Q: "Why do you play it if you know it's a con?"

Mrs. Black: "When I'm with people, I have to keep thinking of things to'say. If I don't I feel uncomfortable."

Dr. Q: "It would be an interesting experiment if you stopped playing 'Why Don't You . . .' in the group. We might all learn something.

Mrs. Black: "But I can't stand a lull. I know it and my husband knows it too, and he's always told me that."

Dr. Q: "You mean if your Adult doesn't keep busy, your Child is exposed and you feel uncomfortable?"

Mrs. Black: "That's it. So if I can keep making suggestions to somebody or get them to make suggestions to me, then I'm all right. I'm protected."

Here Mrs. Black indicates clearly enough that she fears unstructured time. Her Child can be soothed as long as her Adult can be kept busy in a social situation, and a game is a good way to keep her Adult occupied. But in order to maintain her interest, it must also offer satisfactions to her Child. Her choice of this particular game depended on the fact that, for psychiatric reasons, it suited the needs of her special kind of Child.

Other common games are "Schlemiel," "Alcoholic," "Uproar," "You Got Me Into This," "There I Go Again," and "Let's You and Him

Fight." Such games have many similarities to popular contests such as chess or football. "White makes the first move," "East kicks off," each have their parallels in the first moves of social games. After a definite number of moves the game ends in a distinct climax which is the equivalent of a checkmate or touchdown. This should make it clear that a game is not just a way of grumbling or a hypocritical attitude but a goal-directed set of ulterior transactions with an unexpected twist which is often overlooked.

The sequence of moves is illustrated in the game of Schlemiel. In this game the one who is "It" breaks things, spills things and makes messes of various kinds, and each time says "I'm sorry!" The moves in a typical situation are as follows:

1. White spills a highball on the hostess's evening gown.

2. Black responds at first with anger, but he senses (often only vaguely) that if he shows it, White wins. Black therefore pulls himself together, and this gives him the illusion that he wins.

3. White says, "I'm sorry!"

4. Black mutters forgiveness, strengthening his illusion that he wins.

It can be seen that both parties gain considerable satisfaction. White's Child is exhilarated because he has enjoyed himself in the messy moves of the game and has been forgiven at the end, while Black has made a gratifying display of suffering self-control. Thus, both of them profit from an unfortunate situation, and Black is not necessarily anxious to end the apparently unpromising friendship. It should be noted that as with most games, White, the aggressor, wins either way. If Black shows his anger, White can feel "justified" in his own resentment. If Black restrains himself, White can go on enjoying his opportunities.

The "gimmick" in such games almost always has an element of surprise. For example, a careless observer might sympathize with Mrs. White because of her autocratic husband, but the "gimmick" is that while she is complaining about him he is really serving a very important purpose in protecting her from her abnormal fears. In "Why Don't You .. . Yes, But" the "gimmick" has remained concealed from serious investigation through the thousands of years that this game has been played. It may have been observed facetiously that the one who is "It" rejects all the suggestions offered, but the possibility that this in itself might be a source of reassurance and pleasure has not been taken seriously enough to stimulate scientific interest. The clumsiness of the Schlemiel, and the possible secret pleasure he may derive from it, have been discussed, but this pleasure is merely a dividend; the "gimmick" and the goal of the whole procedure, which lie in the apology and the resulting forgiveness, have been overlooked.

156 Analysis of Games

The kinds of games, such as those mentioned above, which are of interest to the student of social dynamics, are of a serious nature, even though their descriptions may bring to mind the English humorists. They form the stuff out of which many lives are made and many personal and national destinies are decided. Any set of transactions that occurs repeatedly in a group, and that can be analyzed on two levels like the illustrations in Figures 26 and 27, is probably a game. The diagnosis is confirmed if an ulterior motive can be found which leads progressively to the same climax again and again.

SUMMARY The most significant hypotheses offered in this chapter are as follows:

1. With appropriate classification of group proceedings, it can be said that there are only a limited number of behavioral options open to an individual member.

2. The social function of pastimes is to serve as an innocuous matrix for tentative excursions of the Child.

3. Certain repetitive sets of transactions have an ulterior motive and lead to a climax which is concealed by the superficial indications.

SPECIAL TERMS INTRODUCED IN THIS CHAPTER Withdrawal Intimacy

Extraneous fantasies Pseudo-intimacy

Autistic transactions Psychological advantage

Ritual Social advantage

Stroke Psychological level

Pastimes Social level

Games

TECHNICAL NOTES

The elements of rituals, especially of greeting and farewell rituals, are called "strokes" for reasons which will become clearer in the next chapter.

The word "gimmick" is particularly appropriate to games. Its original technical meaning referred to a device placed behind a wheel of fortune so that the operator could stop it in order to prevent a player from winning. Thus it is the hidden snare which is controlled by the operator and assures him of an advantage in the pay-off. It's the "con" that leads to the "sting."

For further information and descriptions of some of the other games mentioned, the reader is again referred to my book Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy (loc. cit.). Stephen Potter is the chief representative of the humorous exposition of ulterior transactions (e.g., Lifemanship, New York, Henry Holt & Company, 1951; Gamesmanship, id. n.d.). An extensive discussion and thesaurus of pastimes and games is contained in my book Games People Play (New York, Grove Press).

t2

/tdjutttttent o£ t&e Individual fo t&e (fnoufr

Each individual enters a group with the following necessary equipment: (1) biologic needs, (2) psychological needs, (3) drives, (4) patterns of striving, (5) past experience, and (6) adjustive capacities. It is just this equipment which makes it possible for leaders to exploit their members for good or evil, and which hampers the independent flowering of individual personalities. But that is another matter which does not belong in a technical book on group dynamics, any more than a discussion of human morality belongs in a textbook of medicine. After he sees what forces people are up against when they join groups, the reader will be better able to form his own philosophy.

BIOLOGIC NEEDS

The well-known sensory deprivation experiments indicate that a continual flow of changing sensory stimuli is necessary for the mental health of the individual. The study of infants in foundling hospitals, as well as everyday considerations, demonstrates that the preferred form of stimulation is being touched by another human being. In infants, the withholding of caresses and normal human contact, which Rene Spitz calls "emotional deprivation," results directly or indirectly in physical as well as mental deterioration. Among transactional analysts, these findings are summarized in the inexact but handy slogan: "If the infant is not stroked, his spinal cord shrivels up."

As the individual grows up, he learns to accept symbolic forms of stroking instead of the actual touch, until the mere act of recognition serves the purpose. That is why the elements of greeting rituals are called "strokes." What is said is less important than the fact that people are recognizing each other's presence and in that way offering the social contact which is necessary for the preservation of health. Thus, both infants and grownups show a need for, or at least an appreciation of, social contact even in its most primitive forms. This can be easily tested by anyone who has the courage to refuse to

158 Adjustment of the Individual to the Group

respond when his friends say "Hello." The desire for "stroking" may also be related to the fact that outside stimulation is necessary to keep certain parts of the brain active in order to maintain a normal waking state. This need to be "recharged," as it were, by stimulation, and especially by social contact, may be regarded as one of the biologic origins of group formation. The fear of loneliness (or of lack of social stimulation) is one reason why people are willing to resign part of their individual proclivities in favor of the group cohesion.

PSYCHOLOGICAL NEEDS

Beyond that, human beings find it difficult to face an interval of time which is not allotted to a specific program: an empty period without some sort of structure, especially a long one. This "structure hunger" accounts for the inability of most people simply to sit still and do nothing for any length of time. Structure hunger is well known to parents. The wail of children during summer vacation and of teenagers on Sunday afternoon—"Mommy, there's nothing to do!"— recurrently taxes their leadership and ingenuity.

Only a relatively small proportion of people are able to structure their time independently. As a class, the most highly paid people in our society are the ones who can offer an entertaining time structure for those whose inner resources are not equal to the task. Television now makes this advantage available in every home. In a group, it is principally the leader who performs the necessary task of structuring time. Capable leaders know that few things are more demoralizing than idleness, and soldiers have said that risking their lives in active combat is preferable to sitting out a "bore war." Psychotherapists see the same thing in a milder degree when their group patients beg them for instructions as to how to proceed and resent it if a program is not forthcoming. One product of structure hunger is "leadership hunger," which quickly emerges if the leader refuses to offer a program or if he is absent from a meeting and there is no adequate substitute. No doubt there are other factors involved here, but the fact remains that a long unexpected silence at any group meeting or on the radio arouses increasing anxiety in most people.

Because a group offers a program for structuring an interval of time, the members are willing to pay a price for their membership. They are willing to resign still more of their individual proclivities in favor of ensuring the survival of the group and its structure. They also appreciate the fact that the leader is the principal time-structurer, and that is one factor in awakening their devotion.

The reason given by Mrs. Black for playing her games throws some light on why people seek time-structuring. Unless the Adult is kept

busy, or the Child's activities are channeled, there is a danger that the Child may run wild, so to speak, in a way the individual is not prepared to handle. The need to avoid this kind of chaos is one of the strongest influences which sends people into groups and disposes them to make the sacrifices and the adjustments necessary to remain in good standing.

The need for social contact and the hunger for time-structure might be called the preventive motives for group formation. One purpose of forming, joining and adjusting to groups is to prevent biologic, psychological and also moral deterioration. Few people are able to "recharge their own batteries," lift themselves up by their own psychological bootstraps, and keep their own morals trimmed without outside assistance.

DRIVES

On the positive side, the presence of other human beings offers many opportunities for gratification, and everyone intuitively or deliberately acquires a high proficiency in getting as many satisfactions as possible from the people in the groups to which he belongs. These are obtained by means of the options for participation listed in the previous chapter. The surrounding people contribute least to the satisfactions reaped from fantasy and most to those enjoyed in intimacy. Intimacy is threatening for various reasons, partly because it requires independent structuring and personal responsibility; also, as already noted, it is not well suited to public situations. Hence, most people in groups settle for whatever satisfactions they can get from games, and the more timid ones may not go beyond pastimes.

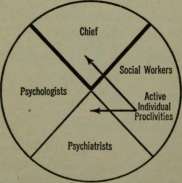

Neverthless, hidden or open, simple or complicated, a striving for intimacy underlies the most intense and important operations in the group process. This striving, which gives rise to active individual proclivities, may be called the individual anancasm, the inner necessity that drives each man throughout his life to his own special destiny. Four factors lend variety to its expression: (1) the resignations and compromises that are necessary to ensure the survival of the group. This is the individual's contribution to the group cohesion. (2) The disguises resulting from fear of the longed-for intimacy. (3) Individual differences in the meaning of intimacy: to most it means a loving sexual union, to some a one-sided penetration into the being of another through torture; it may involve self-glorification or self-abasement. There are differences in the kind of stroking received or given. Most want a partner of the opposite sex, some want one of the same sex, in love or in torment. All of these elements are influenced by the individual's past experiences in dealing with or

160 Adjustment of the Individual to the Group

being dealt with by other human beings. From the very day of birth, each person is subjected to a different kind of handling: rough and harsh or soft and gentle or any combination or variation of these may signify to him the nature of intimacy. (4) Differences in the method of operation, the patterns of behavior learned and used in transacting emotional business with other people.

PATTERNS OF STRIVING

Each person has an unconscious life plan, formulated in his earliest years, which he takes every opportunity to further as much as he dares in a given situation. This plan calls for other people to respond in a desired way and is generally divided, on a long-term basis, into distinct sections and subsections, very much like the script of a play. In fact, it may be said that the theatre is an outgrowth of such unconscious life plans or scripts. The original set of experiences which forms the pattern for the plan is called the protocol. The Oedipus complex of Sigmund Freud is an example. In transactional analysis the Oedipus complex is not regarded as a mere set of attitudes, but as an ongoing drama, divided, as are Sophocles's Oedipus Rex, Electra, Antigone, and other dramas, into natural scenes and acts calling for other people to play definite roles.

Partly because of the advantages of being an infant, even under bad conditions, every human being is left with some nostalgia for his infancy and often for his childhood as well; therefore, in later years he strives to bring about as close as possible a reproduction of the original protocol situation, either to live it through again if it was enjoyable, or to try to re-experience it in a more benevolent form if it was unpleasant. In fact, many people are so nostalgic and confused that they try to relive the original experience as it was even if it was very unpleasant—hence the peculiar behavior of some individuals who are willing to subject themselves to all sorts of pain and humiliation, repeating the same situation again and again. In any case, this nostalgia is the basis for the individual anancasm. This is something like what Freud calls the "repetition compulsion," except that a single re-enactment may take a whole lifetime, so that there may be no actual repetition but only one grand re-experiencing of the whole protocol.

Since the script calls for the manipulation of other people, it is first necessary to choose an appropriate cast. This is what takes place in the course of pastimes. Stereotyped as they are, they nevertheless give some opportunity for individual variations which are revealing of the underlying personalities of the participants. Such indications help each player to select the people he would like to know better,

with the object of involving suitable ones in his favorite games. From among those who are willing and able to play his games, he then selects candidates who show promise of playing the roles called for in his script; this is an important factor in the choice of a spouse (the chief supporting role). Of course, if things are to progress, this process of selection must be. mutual and complementary.

Because of its complexity, it is fortunate that it is not necessary to consider the script as a whole in order to understand what is going on in most group situations. It is usually enough to be aware of the favorite games of the people concerned.

THE PROVISIONAL GROUP IMAGO There are various forces which determine group membership, and the individual is not necessarily attracted mainly by the activity of a group. If it is the kind of group in which he will meet other members face to face, his more personal desires become important. As soon as his membership is impending, he begins to form a provisional group imago, an image of what the group is going to be like for him and what he may hope to get out of it. In most cases, this provisional group imago will not long remain unchanged under the impact of reality; but, as already noted, the internal group process is based on the desire of each member to make the actual, real group correspond as closely as possible to his provisional group imago. For example, a man may join a country club because that will offer him an opportunity to engage in his favorite pastimes. If the club is not equipped for one of them, he may try to introduce it. Membership in any group that includes unmarried people is nearly always influenced by the hope of finding a mate, and this may give rise to a very lively and colorful provisional group imago.

Psychotherapists often have to deal with provisional group imagoes when they suggest that a patient join a therapy group. The patient questions the therapist either to adjust an imago he has already formed from reading or gossip or to start forming one so that he will know what to expect. If the picture offered by the therapist does not meet his desires, the patient will not be favorably inclined and may join only to please the doctor rather than with the hope that "the group" will be of value to him.

While the script and the games that go along with it and set it in action come from older levels of the individual's history, his provisional group imago is based on more recent experiences: partly first-hand, from groups he has been a member of, and partly secondhand, from descriptions of groups similar to the one he desires or expects to join. One branch of the advertising and procurement pro-

162 Adjustment of the Individual to the Group

fessions is particularly concerned with favorably influencing provisional group imagoes.

It should be clear now that each member first enters the group equipped with: (1) a biologic need for stimulation; (2) a psychological need for time-structuring; (3) a social need for intimacy; (4) a nostalgic need for patterning transactions; and (5) a provisional set of expectations based on past experience. His task is then to adjust these needs and expectations to the reality that confronts him.

ADJUSTMENT

Each new member of a group can be judged according to his ability to adjust. This involves two different capacities: adaptability and flexibility.

Adaptability is a matter of Adult technics. It depends on the carefulness and the accuracy with which he appraises the situation. Some individuals make prudent estimates of the kinds of people they are dealing with before they make their moves. They are tactful, diplomatic, shrewd or patient in their operations, without swerving from their purposes. The adaptable person continually adjusts his group imago in accordance with his experiences and observations in the group, with the practical goal of eventually getting the greatest satisfaction for the needs of his script. If his script calls for him to be president, he picks his way carefully and with forethought through the hazards of political groups.

On the other hand, the arbitrary person proceeds blindly on the basis of his provisional group imago. This is typical of a certain type of impulsive woman, who will launch a sexually seductive game immediately on entering a group, hardly glancing around the room to see what company she has to reckon with. Occasionally her crude, unadapted maneuvers may be successful, and she will get the responses her script calls for: advances from the men and jealousy from the women. However, if the other members are not so easily manipulated, she may be ignored or rebuffed by both sexes. Then she is faced with the alternatives of either adjusting or withdrawing; otherwise, she may be extruded by the other members.

The second variable, flexibility, depends on the individual's ability and willingness to modify or sacrifice elements of his script. He may decide that he cannot obtain a certain type of satisfaction from a group and may settle for other satisfactions which are more readily available. Or he may settle for a lesser degree of satisfaction than he originally hoped for. The rigid person is unable or unwilling to do either of these things.

Adaptability, then, concerns chiefly the Adult, whose task it is to arrange satisfactions for the Child. The adaptable person may keep his script intact by modifying his group imago in a realistic way. Flexibility becomes the concern of the Child, who must modify his script to accord with the possibilities presented by the group imago. From this it can be seen that adaptability and flexibility often overlap, but they may also be independent of each other, as consideration of four extreme cases will demonstrate.

The adaptable, flexible individual will carry out his operations smoothly and with patience and will settle for what is expedient. ("Politics is the science of the possible.") He is the rather uninspiring "socially adjusted" person that some school systems take as their ideal, the "common-ground finder" who sacrifices principle to convenience in a "socially acceptable" way. In certain professions, such capacities may be desirable or profitable and may be deliberately cultivated.

The adaptable, inflexible member will carry on patiently and diplomatically but will not yield on any of the goals he is striving for. In this class are many successful business men who do things their own way. The arbitrary, flexible person will shift from one goal to another, showing little skill or patience, and will settle for what he can get without changing his tactics. The arbitrary, inflexible person is the dictator: ready to accomplish his aims without regard to the needs of others and inflexible in his demands. The others play it his way, and he gets and gives what he wants to.

The above descriptions are transactional and refer to the individual's behavior in a group situation, but they resemble character types described from other points of view.

It should be noted that it is the group process and not the group activity that leads to adjustment. For example, a certain type of bookkeeper may never adjust himself to the office group; he may concentrate on his work and do it well while remaining an isolate year in and year out except for participating in greeting rituals.

THE GROUP IMAGO

The complete process of adjustment of the group imago involves four different stages. The provisional group imago of a candidate for membership, the first stage, is a blend of Child fantasy and Adult expectations based on previous experience. This is modified into an adapted group imago, the second stage, by rather superficial Adult appraisals of the other people, usually made by observing them during rituals and activities. At this point, the member is ready to participate in pastimes, but if he is careful and not arbitrary, he will not

164 Adjustment of the Individual to the Group

yet start any games of his own, although he may become passively involved in the games of others. Before he begins his own games, his adapted imago must be changed into an operative one, which is the third stage. This transformation works on the following principle: the imago of a member does not become operative until he thinks he knows his own place in the leader's group imago, and this operative group imago remains shaky unless it has repeated existential reinforcement. To become operative, an imago must have a high degree of the differentiation mentioned in Chapter 5.

Grim examples may be found in the memoirs of officers of secret police forces. Many of these officers felt uncertain of their positions in the hierarchy until they thought they knew how they rated with their superiors, whom they were continually trying to impress in the course of their work. Once they felt that their positions were established, they were then able to differentiate themselves and their colleagues more clearly in their own group imagoes, whereupon they felt free to unleash the full force of their individual proclivities. They grew more and more confident in their atrocious actions and in their relationships with other party members as the approval of their leaders was reinforced.

A more commonplace example of operative adjustment is the case of the inhibited boy in kindergarten. He may find it difficult to associate with the other children until he feels sure that he knows how he stands with the teacher. Of course, this principle is intuitively known to all capable teachers, and they act accordingly. If they are successful, they will then note that "this boy has improved his adjustment and has now made some friends," i.e., he has differentiated some of the other children in a meaningful way. Similarly, in a psychotherapy group, an adaptable member will not begin to play his games until he thinks he knows how he stands with the leader. If he is arbitrary and not adaptable (e.g., the impulsive type of woman mentioned in the previous section), he may act prematurely and pay the penalty.