196 The Therapy of Ailing Groups

A LITTLE BOY'S CLUB Let us now return to the little boy Davy mentioned in Chapter 12, who always wanted to have meetings at his house and who later became a group therapist. When he was about 10 years old he tried to start a club, the Agamemnon Club, but somehow it never got off the ground. A consideration of the 6 basic diagrams soon makes some of its deficiencies clear. Since in this case the diagrams are relatively simple and easy to visualize, it will not be necessary to draw them.

1. The Location Diagram shows the basement of Davy's home. There are some things there to attract little boys: barred windows, places to hide, isolation from grownups and, since Davy's uncle was a physician, certain objects of scientific interest such as tapeworms in bottles, anatomic charts and a broken microscope. If Davy had wanted to start a junior Osier Society or Aesculapius Club, it might have sufficed. But there was nothing there for a group of Agamem-nons: no swords, shields, guns or lances. There were many other places available where courage could be shown and warlike games carried on to better advantage. The first deficiencies were improper equipment and poorly defined activity.

2. The Authority Diagram consists only of a euhemerus and a personal leader. The euhemerus, Agamemnon, was unknown to most of the candidates for membership and had no personal significance for the others. His canon—the infantry and the chivalry of the Trojan War—had been outdated for many centuries and was finished off during the recent hostilities of World War I. In existential reinforcement, Discobolos and Achilles had been replaced by Babe Ruth and Eddie Rickenbacker. The personal leader, Davy, had few of the magical or even the social attributes of leadership in the eyes of his contemporaries and had only one or two loyal followers.

The defects in the authority diagram extended to all aspects: historical (obscure euhemerus); cultural (meaningless canon, outdated culture); personal (naive leadership); and organizational (no mother group). Actually, all the organizer had to offer in this area was a weak warrant: some cards headed "Agamemnon Club" which he had run off on a toy printing set.

3. The Structural Diagram was poorly defined. Eligibility was based on the autocratic provisional group imago of one person, and that had a defect which is fatal in an autocrat: instability. The requirements for admission changed from day to day and from one recruitment speech to another—except for one item: the payment of one cent as an initiation fee, the proceeds to be spent on plums for

the opening meeting. Unfortunately, due to differences in the tastes of various candidates, even this was threatened with erosion into a fruit-bowl which the organizer realized might be financially unattainable. Hence, the external group boundary soon blurred into vagueness. A proper internal structure might have offered some hope. If each candidate had been offered an office, there might have been some action; but Davy had no inkling of the principle of patronage. Under the guise of working zeal, he wanted to reserve for himself all offices except that of vice-president. Structurally, then, the Agamemnon Club was unstable, poorly defined and, in the circumstances, under-organized.

4. The Dynamics Diagram reveals weak cohesion and a profusion of active individual proclivities in the face of which survival becomes precarious. External disruptive forces, represented by Davy's parents, are only potential, but threatening enough to interfere with serious engagement in the internal group process. A vacant lot might have been better and would have allowed more freedom. The deficiencies here are a cohesion which is weak to begin with and is further weakened by continual agitation and a threatening external environment. This sets the stage for termination by decay.

5. The Group Imagoes are poorly differentiated; mainly, the leader is not clearly differentiated in their minds from the members. There is no place for him in their scripts; he is neither fatherly, big brotherly, nor rebellious; all he has to offer is idealism, and they are still too young for that. In fact, he does fit into the scripts of two of the bigger boys but not according to his own provisional group imago. They cast him as an over ambitious boy who is a prospective dupe; they help him recruit, with the idea of eventally running off with all the fruit at the first meeting. Of course, as members of the group apparatus, they excuse themselves from having to pay the initiation fee. Their absconding with the proceeds was the actual occasion for the group breaking up. After that bad beginning, it never met again. But this only meant that it died by unexpected disorganization rather than by the oncoming decay. When the organ of survival itself, the group apparatus, is traitorous, the group is doomed.

6. The Transactional Diagrams were mostly commonplace. There was some organizational work, no time to establish rituals, and much participation in pastimes. The only game played was that which the absconders engaged in, with which the others became involved. There was no belonging or intimacy. Thus, nearly all the transactions were simple, complementary and Adult-Adult; only the two bigger boys carried on ulterior transactions.

198 The Therapy of Ailing Groups

TECHNICAL NOTES

The rule that joint management-labor consultations are superior to separate consultations for each class was introduced to me by Dr. Lester Tarnopol of San Francisco City College.

The problems of plantation labor as they arise in specific situations are recounted from time to time in Pacific Islands Monthly (Sydney, Pacific Publications Pty.).

The significance of attendance in psychotherapy groups, and the normal statistical expectations, are set forth in my paper on "Group Attendance" (loc. cit.).

The Agamemnon Club was started by one little boy, but only a few items would have to be changed for the analysis to apply equally well to such an important failure as the old League of Nations. That is why a consistent approach to ailing groups is so important. The careful study of any group, however trivial, may lead to conclusions which are of universal significance.

rs

The same principles which are used in the therapy of small ailing groups can be applied to larger organizations with 1,000 or more members. It is only necessary to bear in mind that in a small group each member can be dealt with as an individual, while in a large outfit trends have to be taken into account before individual proclivities can be considered. The type of analysis given below is suitable for large hospitals and custodial institutions such as prisons, and with a few modifications can be adapted for business, political and military organizations.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Elysium State Hospital was a modern, well-equipped, well-financed therapeutic community situated, like many of its kind, in a remote part of the state near a small town. There were more than 1,000 patients, and somewhat less than 1,000 employees. Dr. Q, as consultant in social dynamics and group therapy, had an opportunity to become acquainted with the administrative and the personal problems of the staff as well as with the psychiatric problems of the patients.

THE LOCATION DIAGRAM The hospital had been built under the guidance of the best available architectural and psychiatric consultants, and the physical plant was satisfactory to the staff. Structurally, it was of the chordal form, with the Chief's office near the main entrance and the staff offices radiating out from there and penetrating into the wards and the clinical and the occupational departments. Stretching behind the buildings were large grounds for farming, construction projects, and recreation; these were open to patients who were eligible for extramural activities. Around the periphery were quarters for the junior staff members; the senior staff lived in town. Together they formed an important element in the social and the economic life of the area. Some of the patients' families also moved into the vicinity or visited

200 Management of Organizations

frequently over the week-ends. Thus, the town of Elysium sociologically resembled an Army town, company town or college town in an agricultural area, with similar public relations problems to be dealt with by the external apparatus of the hospital.

THE AUTHORITY DIAGRAM The authority diagram was relatively simple, as illustrated in Figure 35. Administratively, the Chief was responsible to the State Director of Mental Health, who was appointed by and responsible to the Governor, who in the final showdown was responsible to the voting public, the well-known "John Q. Citizen." The administrative manual was the State Welfare Code, which was subject to constitutional change by the State Legislature. All administrative acts of the Chief were constitutional and defensible if they obeyed this code. These were his personal and organizational responsibilities. Those aspects gave him little difficulty.

Cultural and Historical

Personal and Organizational

Function

Manual

Euhemerus

Pine!

Electorate

The Press

Mother Group

Governor

Psychiatric Profession

Director of Mental Health

Legislature

J

State

Welfare

Code

Chief

Hospital Regulations

Fig. 35. Authority diagram of a state hospital.

More troublesome was his cultural responsibility, which was to the public through the press. In the general culture of the state it was considered bad form to have more than the barest minimum of absences without leave or other untoward incidents related to the hospital. The public had delegated to the Chief, as leader of an organ of the internal apparatus of their state, part of their imagined omniscience, omnipotence and invulnerability. An undue number of irregularities would mean that he had breached this imaginary contract, which was based on similarities in the group imagoes of a large number of plain citizens.

His historical responsibility was to his own subgroup, the psychiatric profession, under the euhemerus Pinel, the French doctor who had introduced gentleness into mental hospitals and whose picture hung on the Chief's wall. This required of him a scrupulous etiquette toward patients and a relaxed character toward his staff. Thus he was hemmed in by two canons which were sometimes conflicting: the subculture which demanded gentleness toward patients and prohibited strictness in staff discipline, and the general culture which required him to prevent incidents. The contradictions were worrisome in dealing with excited or especially agitated patients. This conflict was his most serious concern, and he solved it through the technical culture by the use of drugs.

The Organization Chart was the well-standardized one which is common to the better class of institutions of this type. The main differences are found in the informal channels of communication. In most states, the formal channels are set forth in the general manual, which is usually part of the Welfare Code, supplemented by a local manual based on administrative conditions at each hospital. Thus, a patient who wishes to speak to the chief or any member of the staff has a legal and an administrative right to send a formal request through formal channels. The informal channels depend on the persona and the personality of the chief in each locality. Within the limits set by the general manual, the chief of such an institution can make independent and usually final decisions regarding all internal matters and, to that extent, is an autocrat. The morale, or state of the group cohesion, depends largely on how he chooses to exercise this authority. In the Elysium State Hospital, the Chief was both accessible and available to the staff and the patients, and his example was followed by other members of the staff. Accessibility meant that informally, with proper etiquette, all channels of communication were open at appropriate times. A patient could stop the Chief or any other staff member without prior notice if they happened to meet in the corridor or on the ward and be assured of a courteous hearing.

202 Management of Organizations

Availability meant that once a request was listened to, a firm decision or effective action would be forthcoming without undue delay.

The situation at Elysium was in contrast to that at two neighboring hospitals. In the first, the Chief chose to be inaccessible except through formal channels. This overfirmness spread through the lower echelons and became characteristic of the group culture. However, it was true that once the Chief was reached, decision or action would be prompt. In the second hospital, there was a high degree of accessibility, but very little came of it; the Chief would talk to anyone at any time, but it was almost impossible to get a firm commitment or reliable backing "from him. In the first hospital, in spite of the availability, there was a high employee turnover which the staff attributed to the inaccessibility; in the second, even with the high degree of accessibility, there was a weak group cohesion which the staff attributed to the Chief's evasiveness and lack of availability or backing.

THE STRUCTURAL DIAGRAM Despite the outstanding qualities of the Chief, there were certain chronic difficulties at the Elysium Hospital which were not peculiar

Fig. 36. Structural diagram of a state hospital.

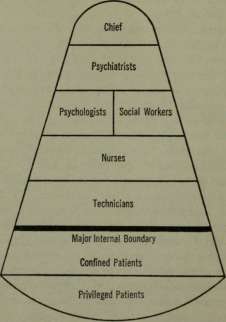

to that institution, and which he was unable to eliminate, although he dealt with them as constructively as possible. These can be understood best by referring to the structural diagram shown in Figure 36. The major internal boundary separates two large general classes of membership: those for whom the hospital is a conditional voluntary group, called the staff; and those for whom it is an obligatory group, called the patients. These two classes can be distinguished by the fact that the staff can legitimately impose and can be observed imposing restrictions on the patients, while the patients cannot legitimately impose restrictions on the staff. But patients can discipline other patients through the self-government provision of the therapeutic community.

These two classes correspond in many important ways to the classes found in an office or industrial plant, generally known as management and workers. Where the hospital has a chief, a professional staff, technicians (formerly called orderlies) and patients, the industrial plant has a chief, executives, foremen and workers. But there are also important differences. In industry, membership is voluntary throughout, although for the individual member the group may be psychologically constrained rather than personal. An Army unit has the same structure, with the major internal boundary between officers and enlisted men; and in wartime with a few exceptions membership is obligatory. In the hospital, the external boundary is open for staff and sealed for patients; in industry it is open for all members; and in the wartime Army it is sealed for all members.

At the hospital, in contrast to industry (strikes) and the Army (griping), there was little difficulty at the major internal boundary. With a few exceptions, the patients and the staff got along well with each other. The main problems arose in the minor structure. The most troublesome agitation occurred at the minor boundaries of the leadership because it was there that the culture lacked firmness. It did not distinguish clearly between psychiatrists (medical personnel) on the one hand, and social workers and psychologists (para-medical personnel) on the other.

This difficulty arose because the principal activity of the hospital was psychiatric treatment, and both the medical and para-medical personnel acted as psychotherapists. The medical personnel felt that this lack of discrimination blurred the therapeutic distinction conferred on them by law and tradition and exposed the patients to therapists whose qualifications could not be judged clearly. The paramedical people resented the tradition that only medical personnel were properly qualified as therapists, and the more intelligent and sensitive ones felt that as individuals they might be better qualified

204 Management of Organizations

by natural endowment than some of the less intelligent and less sensitive medical officers. In general, the medical people stood on their roles in the organizational structure, while the others spoke as per-sonas in the individual structure; hence, they could not come to terms. Their local conflict was related to the same conflict in the general social culture of the state and of the country at large. At that time, constitutional (legislative) agitation was already quite intense over defining the boundary between the activities of the medical and the para-medical professions.

Dr. Q's solution was to side in general with the para-medical people in saying that therapeutic effectiveness depended more on persona than on organizational role, but to emphasize also that physicians were especially' educated for diagnosis and treatment throughout their training, which was not strictly the case with the others. He meant to convey that physicians had a better start in this direction, but that gifted social workers and psychologists could become effective therapists with special training. The emphasis was shifted from therapy as part of the social culture of the hospital to therapy as a technical procedure which could be learned; and from therapeutic skill as something conferred by a constitutional diploma to therapeutic skill as something that resulted from the disciplined application of personal talents, knowledge and attitudes. There resulted murmurings among the psychiatrists which hinted that Dr. Q was a traitor to his class (the class of Constitutional Medical Therapists). But he was careful to speak and act at all time so Hippocratically among them that they could not find him lacking in devotion to the constitutional oath; since they could not find fault with his role or his persona, they had to look for defects in his personality; but their own Adult uprightness prevented them from staying at that level very long, as he knew it would.

THE DYNAMICS DIAGRAM

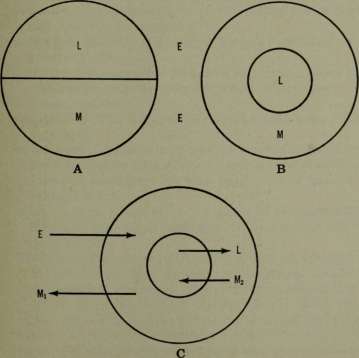

The next set of problems had to do with the relationships between the three forces of the group. (By a curious and unforeseen coincidence, the dynamics problem in a group, arising from the forces Pressure, Agitation and Cohesion [PAC], has the same abbreviation as the structural problem in the individual, arising from Parent, Adult and Child ego states [also PAC]).

While the external pressure in industry is represented by such factors as finance, labor unions and competition, in the case of the hospital it was represented chiefly by the press. Where the head of a corporation would give special attention to his sales staff to combat competition, the Chief of the hospital was particularly careful about

the public relations branch of his external apparatus to combat a bad press, which could be the most powerful threat to the continued existence of the current organizational and individual structure of the hospital.

As already noted, conflicts between the group cohesion and the individual proclivities were influenced by interprofessional competition. This was complicated by the fact that even within the same profession each individual stubbornly insisted on doing things his own way. Each was engaged in his own private game with his patients—a fact which Dr. Q verified by sitting in on different therapy groups—so that there was little belonging or acceptance of others. The most promising weapon against this agitation was their professional training and pride.

Dr. Q's solution was to sharpen further the distinction between activity and process. He suggested a regular clinical seminar which would be compulsory for all staff members engaged in therapy, at which all organizational and personal distinctions would be resigned in favor of improving the effectiveness of treatment. This meant that during the seminar, the Parent and Child in each therapist would be kept in abeyance as far as possible in exchange for the privilege of complete Adult freedom to discuss the material presented. This seminar would be conducted by a senior administrative staff member who was not engaged in therapy and therefore would not have a competitive, dystonic proclivity. It would have to be someone who understood transactional analysis, so that he could conduct himself as an Adult with as little interference as possible from his own Parent and Child, in order to be able to deal effectively with outbursts of Parent or Child from the other staff members. The object was to increase their Adult thoughtfulness and prudence by making them give a public account of their activities and present their work for professional evaluation. There would be certain dangers in requiring adjustment from some of the more touchy staff members, and the skill of the moderator would have to be depended on to avoid this.

For such a procedure to be effective, it was advisable for the seminar to be held weekly at a fixed hour. If the hour were changed frequently, or the intervals between meetings were long or irregular, it would be too easy for rebellious members to forget to come or to make other appointments absent-mindedly. But if it was fixed in their minds that every Monday at 3 p.m., say, they were obliged to attend, it would be harder for them to find excuses to stay away. And Dr. Q knew from experience that it would be more difficult for them to change their individual proclivities if the intervals between meetings were longer than a week.

206 Management of Organizations

THE GROUP IMAGOES

The clearer it became to the staff members that their positions in the imago of the Chief would be influenced by their professional competence rather than by their personal operations (i.e., by their working effectiveness rather than by their skill at games), the more attention they would pay to the former. Of course, this made it difficult for the less competent workers, but tactful handling could soften any bad effects in this regard. However, even if the shift in emphasis from competence in and willingness to play games over to competence in and willingness to do good work resulted in resignations, no harm would be done. In the past forthright people had resigned because the organization was gameridden; in the future, less competent people, who tried to get by on their games, would resign because of the high working standards. Where before the good people had been weeded out, with obvious disadvantages to the hospital, now the less desirable people would be weeded out, with obvious advantages. However, this would require the Chief to be more hard-boiled, since it is often easier for a leader to let a good worker resign than it is for him to let a good game-player go, which is why it is so easy for an organization to remain stagnant or go downhill, and so hard for it to improve. (Various governmental patronage organizations, versus the Bureau of Standards, a skill organization, come to mind.)

A special problem in relation to group imagoes was a tendency for some of the senior staff members to discuss the private structure of the group at staff conferences, doing a kind of diluted group therapy in the course of business or educational meetings. This is a frequent temptation in organizations engaged in group therapy. The idea is that if group therapy is good for the patients, it should be good for the staff members also. That may be true, but it requires more careful thought than it is usually given. If the staff needs such therapy, then there should be a special therapy group for them, but it should be quite distinctly separated from all other staff meetings and should be explicitly labeled. Otherwise, the following situation arises. A member who wants to say something to the point at a business meeting or training seminar feels that he never knows when he may be called upon to analyse his motives for saying it. He feels rightly that he is involved in a game of Psychiatry. Therefore, he has a tendency either to refrain from speaking, or to tailor what he says to the way the game has been going. In this way the activity of the meeting suffers, and the possible therapeutic benefit which can be derived from such a setup is not worth the sacrifice.

Furthermore, on general psychiatric and social dynamic principles, therapy for the staff of an organization is best done by an uninvolved,

neutral outsider. The fewer games his patients have an opportunity to play with him outside the therapy hours, the more straightforwardly a therapist can do his work. On the other hand, adding a game of Psychiatry to those already played between the staff members of an organization does not contribute to its working effectiveness. When Dr. Q presented these considerations to the hospital administration, they appeared to receive them not only with gratitude but also with relief and decided to eliminate "group dynamics" from their business and educational meetings.

THE TRANSACTIONAL DIAGRAMS

The staff of the hospital (at educational meetings), and many of the patients in their therapy groups, received instruction in structural and transactional analysis. Thus, they learned to distinguish Parent, Adult and Child in their relationships with people around them and found that by giving some thought to what they said, they could get more acceptable responses. Or, if something went wrong, they might be able to find the crossed transaction and avoid a future repetition of an unpleasant or difficult situation.

The most important problem here was the therapeutic technic of those engaged in group therapy. As noted, by sitting in at group meetings Dr. Q found that almost every therapist in the hospital was indulging his Parent or Child without realizing it. Many transactions which they thought of as Adult therapeutic operations were actually parts of their own games, usually games which they would not play so openly with their wives or colleagues but were very likely playing with their actual children at home and had apparently learned from their own parents. In some cases it was safe to mention these observations briefly, with possible constructive effects.

SPECIAL TERMS INTRODUCED IN PART IV Flabby culture Accessibility

Brittle culture Availability

Everything that has been written about man's relationship to man belongs in a sense to the literature of social dynamics. According to Breasted, the earliest treatise on this subject is the Maxims of Ptah-Hotep (3000 B.C.), and what Breasted calls "the dawn of conscience" is also the morning of group dynamics. It is exciting to speculate that the first psychodynamic groups (groups involving the displacement of feelings to substitute objects) were formed by our ancestors when they put magic (apotropaic) paintings on cave walls during the late glacial period; for this making of magic and its delegation to a special individual, the artist, is the oldest known possibility of a consciously planned organization of living beings employing "psychological artifacts."

More specifically, however, there are older writings which foreshadow, or even surpass, the findings and the concepts of our present-day knowledge; and these, together with certain recent publications, should be part of the intellectual equipment of those who wish to regard themselves as literate and disciplined therapists of ailing groups. The following is suggested as a minimum reading list. The bibliographic references to the works mentioned will be found on pages 223 to 226.

THE ANCIENT WORLD There must have been just as large a proportion of perceptive men and women in the population of the ancient world as there is nowadays, but few of them had the opportunity to devote themselves to writing. Those who did have bequeathed to us some provocative ideas about the workings of organizations and groups, particularly concerning the qualities of leadership and the relationship between the leader and the members.

India The most pertinent of the Indian classics is the Hitopadesa, or Book of Good Counsels y in which a teacher imparts instruction in good leadership to the king's sons by means of fables, interlarded with quotations from the Vedas and the Mahabharata. These quotations are said to date from 1300 to 350 B.C.

210 Suggested Reading

China The classical literature of China is much more precise in this respect than many people realize. There are two philosophers in particular whose writings are interspersed with group dynamic principles: Confucius (551-479 B.C.), and Lao Tzu, a mythical figure representing a collection of writings from the 3rd century B.C. Even more specific is Sun Tzu (500 B.C.), whose Art of War is said to be the oldest military treatise in the world.

Greece and Rome

Of course, the best known classics in this field are the Politics of Aristotle and The Republic of Plato. Marcus Aurelius gives many hints about the qualifications, duties and especially the responsibilities of a leader. Less well known, but perhaps even more instructive in a practical way, is the De Re Militari of Vegetius, who flourished in the 4th century B.C. This was the most influential military treatise in the Western world from Roman times to the 19th century. Euhe-merus belongs in this period (300 B.C.).

In general, the group dynamics of the ancients was chiefly concerned with political and military matters.

THE MIDDLE AGES In the Western world the serious literature centered mainly around theology, although lawyers and political scientists were also active. Some provocative ideas are offered by such writers as St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas.

THE RENAISSANCE The most important writer of this period is Machiavelli. While he is notorious for his knowledge of the dynamics of intrigue, he is an equally profound student of the principles of good leadership and the correction of defects in this area.

A.D. 1500 TO 1800

During this period the relationship between the leader and the members was being subjected to more formal theoretical analysis, particularly by lawyers. The epoch is outstanding for its active observers and good thinkers. Their material was derived not from experiment, but from nature—i.e., from actual political situations, so that their principles could be tested against historical outcomes. Almost all the topics which have been dealt with in this book were discussed by the great philosophers of this era.

Their arguments are summarized by Otto Gierke in the fourth volume of his Das deutsche Genossenschaftsrecht (1913). The pro-

fundity of thought during these centuries was so great that it may be said that anyone who is not at least acquainted with it is a primitive in the field of group dynamics. Fortunately, the most pertinent material has been abstracted and translated from Gierke by Ernest Barker, Professor of Political Science in the University of Cambridge. Those who are not sufficiently motivated to read the text should at least read Professor Barker's stimulating introduction.

THE 19TH CENTURY

In the early years of this century the formal (structural and dynamic) approach was continued, and its value as an approach analyzed, by Auguste Comte (1798-1857), while the historical approach is represented by Hegel (1770-1831) in his Philosophy of History. The latter half of the century is marked by a distinct shift under the influence of two writers: Darwin and Marx. The evolutionist viewpoint quickly made itself felt and is presented in the works of Herbert Spencer and Walter Bagehot. As everyone is keenly aware nowadays, Karl Marx's writings gave rise to an enormous literature, whose influence on the study of group dynamics is most concisely illustrated by George Plekhanov's short work The Role of the Individual in History and Frederick Engels' less well known treatise The Origin of the Family. In the final decade, the psychological viewpoint emerged in Le Bon's celebrated treatise Psychologie des foules, which was almost immediately translated into English and was the principal stimulus for Freud's work on group psychology.

De Tocqueville (Democracy in America), J. S. Mill and Nietzsche represent other approaches which were influential during this period.

THE 20TH CENTURY

The modern scientific literature falls largely in three provinces: sociology, social psychology and group psychotherapy. Two of the notable early landmarks were Trotter's Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War (1916) and Freud's Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921). Freud's Totem and Taboo (1912) is interesting collateral reading.

The sociologic literature has been ably reviewed many times. One of the most easily available surveys is that of Victor Branford, who favors "synthetic generality" rather than "biased particularism" for a genuine sociology.

Two viewpoints of social psychology are presented by Krech and Crutchfield, and J. F. Brown, respectively, the latter based on Lewin's topological and field theory. These are both college texts. A more technical consideration, including historical and theoretical back-

212 Suggested Reading

ground, an annotated bibliography and a selection of papers relating to current research is found in the recent symposium on small groups edited by Hare, Borgatta and Bales. A similar collection has been published by Cartwright and Zander.

Slavson and Scheidlinger have reviewed the literature of group psychotherapy, the latter with more inclusive and detailed discussion, particularly of Freud's theories.

From all these recent sources, it would appear that research in this field now follows one or other of the usual academic alternatives. The data is purposefully gathered and is then either subjected to statistical evaluation or fitted into a preconceived framework. These are both operations which can be performed by machines. As might be anticipated, the result is that in the whole of the vast "modern" literature there are few creative ideas as compared with the older writings. There is a conspicuous absence of what might be called "creative meditation about nature," that type of thinking which is characteristic of theoreticians such as Newton, Darwin and Freud, experimenters such as Galileo, Harvey and Fabre, and such dramatic problem-solvers as Archimedes, Kekule" and Poincare.

Fortunately, creative thinking in the field of group dynamics does exist, but, because of its informal character, it is often neglected by reviewers and professional research workers. Some of the most interesting ideas have come from psychiatrists, possibly because they have more opportunity for "creative meditation" than most other groups of social scientists, who are more subject to academic pressures. Curiously enough, of the four who have (in the writer's opinion) made the most provocative observations, three are Englishmen; and the American, Burrow, worked in a small village. One is reminded of the epigram: "Penicillin could not have been discovered in America because the laboratories are too tidy." The work of these four writers —Bion, Burrow, Ezriel and Foulkes—is abstracted below. The reference numbers refer to articles by each author whose titles will be found in the bibliography.

Bion W. R. Bion, of the Tavistock Clinic (London), studied small groups in a naturalistic way by pushing aside preconceptions. He published his findings in a series of seven articles (1948-1951) in the periodical Human Relations and summarized them in an eighth article which appeared in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. They have recently appeared in book form. 8 Few people claim to understand them completely, but some of the clearest and most instructive points can be simply stated as follows:

1. The group takes on a mature structure, the work group, to avoid certain kinds of groups which are feared: namely, the "basic assumption" groups. 3 The work group is concerned with reality and therefore has some of the characteristics of "the (Freudian) ego." 7

2. The group demands a structure consisting of a leader and his followers and has a resentful (paranoid) attitude toward a leader who does not show the characteristics they think proper. 1-3

3. The behavior of the members is influenced by a conscious or unconscious idea of how the group feels toward them, but they prefer to deny this. 2

4. The "group mentality" expresses the will of the group, to which individuals contribute anonymously in very subtle ways. The group mentality makes it disagreeable for an individual who does not behave according to the basic assumptions. 3

5. The "group culture" arises from the conflict between the individual's desires and the group mentality. It includes the structure of the group at any given moment, the occupations it pursues, and the organization it takes on. 3

6. Whenever two people become involved with each other, both the group and the pair concerned make the "basic assumption" that the relationship is a sexual one. 3 This is the first basic assumption. Such a "pairing group" becomes anxious because of the feeling that they are dealing with an "unborn genius." 7 (It is hard to understand what Bion means by this).

7. When people meet in a group, the group assumes that their purpose is the preservation of the group. The second basic assumption is that the group will use the only two methods of self-preservation it knows, fight or flight. Pairing is allowed because it is an alternative way to preserve the group. 3

8. A third basic assumption is that an external object exists which will provide security for the immature organism. 3 This gives rise to the dependent group, which is based on something like a religious system. Independent thought is stifled, heresy is righteously hunted, and the leader is criticized because he is not a magician who can be worshipped; a rational approach on his part is rejected. 4

9. The dependent group opposes development on grounds of loyalty to its leader or to its traditional "bible," the word of the group god; or to somebody who has been made into the group god in order to resist change. 7 If left to itself, the dependent group will choose as its leader the least healthy member: a paranoid schizophrenic, a severe hysteric or a delinquent. 6 If the leader (e.g., Bion) does not interfere, the group tries to claim that he is both mad and dependa-

214 Suggested Reading

ble. 6 Since this is a contradiction, the group becomes uneasy. Then they try to bring in other groups to solve the problem. 6

10. The basic assumptions which are not active at any given moment are stored in a "proto-mental" system in which physical and mental are blended. There the relationships of the three basic assumptions become complicated. 6

11. Jt is important to study what occurs when the group passes from one culture to another, as from the work group to one of the three basic assumption groups. 3

12. The basic assumption groups attract the members because they give the illusion that a member can sink himself in a group without needing to develop. 4 Thus the group splits into an unsophisticated majority who oppose work, and a sophisticated minority which wants to develop. 7 The work group is constantly disturbed by influences which come from the basic assumptions 7 ; nevertheless, the work group wins in the long run. 7

13. The work group has to prevent the basic assumptions from interfering. Group organization steadies the work group; without organization, it might be submerged by the basic assumptions. Organization and structure are its weapons. They are the product of co-operation and their effect is to demand still further co-operation. A group acting on a basic assumption needs no organization or co-operation. 7

14. In the basic assumption groups there is a spontaneous instinctive co-operation called "valency." Interpretations concerned with valency can and should replace psychoanalytic interpretations in group therapy. They may reduce the group to silence. It can then be shown that there is no way in which the individual in a group can "do nothing," even when he does "nothing." 6

15. Psychoanalytic interpretations are justified by the therapist as attempts to overcome resistance but are really attempts to get rid of the "badness" of the group, its apparent unsuitability for therapeutic purposes. Such interpretations only strengthen the dependent tendencies of the group. 6

16. The meeting of the group in a particular place at a particular time has "no significance whatsoever in the production of group phenomena." These exist anyway even before their existence is evident. 7

17. The group brings out things which seem strange to an observer unaccustomed to using groups. 7

18. Plato emphasized harmonious co-operation in the work of the group. Augustine postulated harmony through each individual's rela-

tionship with God. Nietzsche suggests that a group achieves vitality only by the release of aggressive impulses. 7

At times Bion speaks modestly of these reactions as occurring "in every group of which I have been a member," 1 and talks about what it means "to be in a group in which I was present." 1 However, at other times, he speaks of the things he observes as though they were universal to all groups, including historical groups. For example, when he says that "if left to itself, the dependent group will choose as its leader the most ill member," 6 he does not make it clear whether he thinks that is due to his own very distinctive and interesting method of handling groups or is a universal occurrence. Lombroso's ill "men of genius," to take a large category, did not find it easy to be "chosen" as leaders, while R. Sears found that patient "leaders" showed more uniformity in kind than in degree of disturbance. In fact, Bion's concept of "basic assumption leaders" brings up the problem of whether there can be any true "leader" in a therapy group other than the therapist, no matter how strenuously a therapist tries to avoid active involvement. To use his own words, even a therapist who "does nothing" cannot do "nothing."

Bion has studied carefully certain important aspects of group psychology and has re-emphasized the value of observing groups in a naturalistic and unprejudiced way.

It remains to be seen whether the things Bion describes are always present in every group, or whether they only occur occasionally or in special kinds of groups: i.e., whether they are obligatory or incidental.

Burrow

Trigant Burrow, of the Lifwynn Foundation in Westport, Connecticut, was a prolific writer. The present summary is based on a study of eight papers, six written by him, and two by two of his followers, Hans Syz and William Gait. This was the material sent by Dr. Burrow when he was asked for a representative selection of his work. As with Bion, and for that matter with Freud, his ideas are easier to understand when they are in the making than after they have been elaborated as a result of further experience. Then the system may seem to an outsider too deep to follow clearly without personal instruction and interpretation from the originator or a well-trained disciple.

In the first paper, "The Basis of Group Analysis," published in 1928, 1 Burrow proposes a form of group therapy as "a valuable adjunct to our present endeavors in behalf of neurotic and insane patients." He states that "for several years I have . . . been daily occupied with the practical observation of these inter-reactions as

216 Suggested Reading

they are found to occur under the experimental conditions of actual group setting." He already follows practices which many therapists came to prefer 15 or 20 years later on the basis of their own experience.

The number of persons composing a group session has come to be limited, empirically, to about ten. . . . The sessions are held once weekly and continue for one hour. The object of the group-analysis is to give the individual the opportunity to express himself in a social setting without the inhibitions of customary social images.

He makes clear that this is an attempt to uncover, through the application of psychoanalytic principles, the underlying meaning of social interchange. Although in 1941 he stated that

the group method of analysis . . . bears no relation to the recently adopted measures of treatment now conducted under the name of group-therapy, 2

it is clear from the foregoing that Burrow is the originator of what is now called group analysis or analytic group psychotherapy. On these grounds it can be claimed that, in addition to his later firsts in the study of group dynamics, Burrow was the first rational, systematic psychiatric group therapist. In fact, in many ways he may be regarded as the outstanding pioneer in the whole science of the study of small groups. Because he held some unorthodox views and stated them in a specialized way, his work is generally ignored or is given only the briefest passing mention, except among his own disciples. In his 1928 paper, he anticipated Bion to some extent in discovering what Bion calls basic assumptions, especially in regard to flight, fight and dependency; he anticipated Ezriel in analyzing "the here and now" or, as Burrow puts it, "the immediate group in the immediate moment"; and he anticipated Ackerman's discussion of "social roles." For that matter, in the last connection, Jung (1920) anticipated Burrow.

Burrow's work led him into a special consideration of the problem of attention, which had already interested him as early as 1909. He regards the behavior of people in groups as unnatural. Every member of a group, normal or neurotic, "appears to be acutely sensitive to the impression he creates upon others." 1 He is so preoccupied with this problem that he is actually unable to become a member of a group. Instead of being co-operative in the real sense of the word, he is at all times hostile and competitive. In fact, his whole participation in the group is clouded by a superstitious outlook.

Beneath the outer expressions of so-called normal communities there are the same fears, the same repression, insecurity, and evasion—the same

emotional substitutions and guilt, the same unilateral secrecy and self-defense; the same superstitions, anxieties and suspicions; the same elations and depressions, whether transient or prolonged; in short, the same neurotic reactions that characterize the isolated patient. 6

This attitude of hostile, superstitious, competitive self-consciousness is connected with a special kind of befogged attention which Burrow terms "ditention." But through experience, he found a technic for inducing another kind of attention, which he calls "cotention," in which the individual functions as a whole in co-operative harmony with his environment. The state of cotention is associated with physiologic changes. In his subjects, the respiratory rate dropped from an average of about 10 per minute in ditention to about 3 per minute in cotention; the oxygen absorbed per minute remained about the same, but oxygen was utilized much more efficiently in the cotentive state. 2 There were also changes in the eye movements and the electroencephalograms. 3

It is Burrow's idea of cotention which is somehow difficult for outsiders to understand clearly, and this is probably the reason why his work has not been influential in a wider circle of group psychologists and group therapists. However, there is no doubt that in many groups there is at times a cessation of the normal attitude of self-conscious rivalry, and that sometimes under these conditions there is a rather profound change in the atmosphere of the group, an almost religious attitude which is quite different from any other experience in a group. Because this atmosphere is so impressive and meaningful and has apparently been overlooked by most "scientific" group workers (perhaps just because they are "scientific"), Burrow's work with cotention deserves careful consideration.*

Because his sentences are often hard to sort out, it is not easy to extract his ideas, but some of the principal ones, in somewhat simplified form, are as follows:

1. Group or social analysis is the analysis of the immediate group in the immediate moment. 1

2. A social group consists of persons each of whom is represented by the symbol he calls "I" or "I, myself," 1 the I-persona. 6

3. This symbol is accepted by the other individuals in the group. It is the basis for their intercommunication; 1 they connive with each other in accepting each other's distortions of self. 6

4. The social image shifts the individual's interest to his awareness of himself in respect to others' awareness of him. By virtue of this image each one of us tends to enact a given role, to portray a certain character or part in the social scheme of things. 1

* Recent experiments at the San Francisco Social Psychiatry Seminars indicate that cotention is probably closely related to game-free intimacy.

218 Suggested Reading

5. The individual is continually matching his impression or image of himself with the image or impression which others have of him. 1

6. There is no difference between the social image of the neurotic and social images as they occur in normal individuals. Neither can attain a rational attitude toward these private images. 1

7. The social image is tied up with early anthropomorphic ideas and is linked with hints of the supernatural. 4

8. Feelings are persistently distorted in the reactions of the social community, so that private opinions with personal interpretations constantly override the evidence of the senses. 4

9. As a result, man sees in outer objects a meaning not belonging to the object itself; therefore, man's world comes to be tinged with fanciful attributes of his own making. 4

10. We fail to recognize the dictatorial influence of the father-image in our current social relationships. 4

11. Man must recognize that he uses purely emotional symbols at the expense of his integrity as a species. 4

12. There are two aspects of attention in the social process. In ditention, the affecto-symbolic image is dominant and distracting due to the intrusion of the self-image. In cotention the affective element is eliminated, and the organism's total relation to the environment resumes its primary unconditioned supremacy. 4

13. Projection has become a universal reaction in man. It clutters his brain and impairs his natural channels of social contact and communication. 6

14. Personalistic concepts are deviations from the natural growth processes; they are in the nature of conditioned responses which are imposed by the child's contact with the world of adults. Co-operative behavior among children is more primary than the competitive response. (Gait)

15. Man's behavior is at present guided by a dream state, as it were, by the image of an egocentric universe, due to a false stress on his capacity to form and employ the symbol or image. A breach is thus created between human beings through the exercise of their own adaptive assets. He tries to compensate for this uncertainty by further manipulations of this very same adaptive configuration. (Syz)

EZRIEL

Henry Ezriel, of the Tavistock Clinic in London, has published three communications about group dynamics and the technic of group therapy which are of special interest. His conclusions may be summarized in part as follows:

1. One individual meeting another will try to establish the kind of relationship between them which will ultimately diminish the tension arising out of relations which he entertains with unconscious fantasy objects. 1 2

2. Each member brings to the group meeting some unconscious relationships with "fantasy objects" which he unconsciously wishes to act out by manipulating the other members of the group. 1 2

3. The behavior of fellow patients in the group acts like the stimulus of a projection test such as the Rorschach, provoking reactions born out of unconscious fantasies. Certain actions on the part of the analyst have a similar effect. 1 2

4. The common denominator of the unconscious fantasies of all the members is represented by a common group tension or common group problem, of which the group is not aware but which determines its behavior. 1 2

5. In dealing with this common group tension, every member takes up a role which is characteristic for his personality structure because of the particular unconscious fantasy he entertains, and which he tries to solve through appropriate behavior in the group. 1

6. The role which each member takes in the "drama" performed in the session demonstrates his particular defense mechanism in dealing with his own unconscious tension. 1

7. The "transference situation" is not something peculiar to treatment but occurs whenever one individual meets another. Manifest behavior then contains, besides any consciously motivated pattern, an attempt to solve relations with unconscious fantasy-objects, the residues of unresolved infantile conflicts. 1 2

8. Each member projects his unconscious fantasy-objects to various other members and tries to manipulate them accordingly. Each stays in a role assigned to him by another only if it happens to coincide with his own fantasy and if it allows him to manipulate others into appropriate roles. Otherwise, he will try to twist the discussion until the real group does correspond to his fantasy-group. 1

9. The individual tries to diminish tensions either in activities which serve only this purpose or by activities superimposed on his conscious needs or the demands which the environment makes on him. 1

10. Everything a patient says or does during a session gives expression to his need in that session for a specific relationship with his therapist; he attempts to involve the analyst in the relations which he entertains with his fantasy objects and with their representatives in external reality. 3

220 Suggested Reading

11. There are three kinds of object relations: the required relationship which the patients try to establish within the group and in particular with the therapist; another, which they feel they have to avoid in external reality, however much they may desire it; and the calamitous one which they feel would follow inevitably if they entered into the secretly desired avoided relationship. For example, a group of patients required an intimate Christian name relationship among themselves in order to avoid a nickname relationship with the therapist which might, they feared, result in a calamitous rejection. 8

12. Strachey emphasized that only the analysis of the "here and now" relationship represents a "mutative" interpretation, i.e., one which can permanently change the patient's personality (which means his unconscious needs). Rickman and others hold that none other than transference interpretations need be used. 2

13. In the group, "here and now" interpretations get around the difficulty that the therapeutic group is an artifact which has no common infantile history. They also enable us to deal effectively with the patient's persecutory feelings which are prominent when extra observers are present. 3

14. At times all the members of the group may be driven by forces beyond their control into what they themselves consider to be a useless discussion. For example, they may criticize a member who intellectualizes by themselves intellectualizing. 3

15. The therapeutic group has the advantage that its preformed structure is of comparatively small influence as compared with the unconscious forces in each member. In a task group, real clashes of interest are hopelessly intermingled with unconsciously determined conflicts. 3

16. The detailed examination of every remark made by patient and analyst in the group and the development of a set of dynamic concepts seem to be promising approaches for the formulation and the testing of hypotheses about the dynamics of human behavior. 3

Ezriel's view that the therapeutic group is an artifact that has no common infantile history 3 tests his implication that what occurs in groups is essentially based on transference. 1-3 He recognizes the feared calamity as a projection 3 while linking the paranoid attitude of the group to the presence of outside observers. 3 He belittles the importance of the preformed structure of the therapy group and considers it hopeless to try to separate the task phenomena from the "unconscious conflict phenomena" in task groups. 8 These are all matters which seem to invite further study. The mutual manipulations of the members have been considered in more detail by G. Bach under the heading of "set-up operations."

Foulkes Among the writings of S. H. Foulkes, of the London Institute of Psycho-Analysis, is a particularly striking article on leadership. Foulkes supports Bion's position that the therapist must avoid approaching the problems of group dynamics with a preconceived frame of reference:

The observer [should] avoid the fallacy of transferring concepts gained from the psychology of the individual, in particular psychoanalytic concepts, too readily to this new field of observation. ... He will find all these, to be sure, in operation; but he will not learn much that is new.

By merely observing what happens before him, he will learn more about the dynamics of the group and,

indeed, new light will be thrown upon the mechanisms in individual psychoanalysis. . . . Group psychology must develop its own concepts in its own rights and not borrow them from individual psychology.

Foulkes' conclusions regarding leadership may be summarized as follows:

1. The group-analytic group is a caricature of a group, and its leader does not lead.

2. There are two basic problems in the group. The manifest level concerns the relationship to other people in adult life and contemporary reality. The other concerns the relationship to parental authority, as represented in the primordial image of the leader, and corresponds to past infantile and primordial reality.

3. The leader activates both analytic and integrative processes. Anxiety caused by the uncovering of hitherto unconscious material is balanced by the increasing strength of the group. The group can balance the impact of ever-new sources of disturbances through its own growing strength.

4. The first basic problem of social life is the clash between the individual's own egotistic needs and impulses and the restrictions imposed by the group. The individual learns that he needs the group's authority for his own security and for protection against the encroachment of others' impulses.

5. Therefore, he has to create and maintain the group's authority by necessary modifications of his own impulses. In return for this sacrifice he receives the support of the group for his own particular individuality. He must tolerate others if his own claims are to be tolerated and must restrict in himself what he cannot tolerate in others. That this happens on a manifest level is only possible because the conductor does not play the part of a leader.

6. In the unconscious fantasy of the group, the therapist is put

222 Suggested Reading

in the position of a primordial leader image; he is omniscient and omnipotent, and the group expects magic help from him. But while it is true that the family is a group, it is not true that the group is a family.

7. The group can reanimate directly the archaic inheritance of the "primal horde" psychology, as described by Freud. (And, one may add, as stressed by Klapman).

8. As a result, the group shows a need and a craving for a leader in the image of an omnipotent, godlike father figure, an absolute leader, a position which the therapist cannot lose, although he may spoil it. (This craving was the clearest phenomenon noted by Bion 1 and has been further studied by Berne, Starrels and Trinchero.)

9. "The paramount need is to create a scientific view of group dynamics and such concepts that will enable us to understand and exchange each other's experiences and problems by expressing them in a language that is commonly understood."

10. There is a nucleus to the leader's personality, not at present further reducible by science, more by art and religion, a primary rapport, without which he cannot awaken or bind the spell of "the old enchantment."

There is some contradiction in Foulkes' concept of the therapist as a conductor who does not really lead, and the fact that no matter what the therapist does, he cannot lose his position as an absolute leader in the unconscious fantasies of the members. In addition, the group craves a "father-figure"; this rather contradicts the idea that the group is not a family. In many ways, it might be more consistent to reverse the dictum that "the family is a group, but the group is not a family," and say instead: "The family is not a group but the group is a family." Some aspects of this problem have been discussed by Beukenkamp and by Grotjahn.

Moreno In addition to these four, the student should also familiarize himself with the sociometric concepts of J. L. Moreno.

METHODOLOGY Those students of group dynamics who are not already familiar wtih psychoanalytic theory, or who have not taken it seriously enough, will enrich their powers of observation and evaluation, as well as discover a large body of important literature in the field, by remedying this deficiency. Many of Freud's works are now available in widely distributed paperback books. Those who wish an easily digestible resume are referred to the writer's popular exposition of the subject (Berne).

As to general methodology, J. Bronowski's review of R. B. Braith-waite's "Scientific Explanation" may be quoted. Braithwaite, who is Professor of Moral Philosophy at Cambridge, does not entirely agree with Bertrand Russell's maxim that: "Wherever possible, logical constructions are to be substituted for inferred entities." Bronowski states:

We must look for the evidence for the laws in the cross-connections between them. What we must adduce, I think, is the amount of simplification or order the laws bring into the wilderness of natural facts.

Other modern methodologic approaches which are easily available and can be understood to some extent by the nonspecialist are those of Bohr, Cantril, Erikson, Planck, Richter, Ruderfer, Stewart, von Bertalanffy, Weaver and Wiener.

SUMMARY In this survey of the literature, from India and China, the ancient Oriental capitals of civilization, through Athens, Vienna, London, and New York to San Francisco, one principle of group dynamics has been recognized throughout. This was as aptly and concisely stated by Confucius as by any of his successors in the field:

The people are pleased with their ruler because he is like a parent to the people. If the deportment of the Prince is correct, he sets the country in order.

This is an attempt to answer the question which is fundamental to all theories of group dynamics: Why does anyone ever do what someone else tells him to?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ackerman, Nathan: "Social Role" and Total Personality, Manuscript,

1950. : The Psychodynamics of Family Life, New York, Basic Books,

1958. Aristotle: Politics, translated by Jowett and Twining, New York, Viking

Press, 1957. : Poetics, translated by Jowett and Twining, New York, Viking

Press, 1957. Aurelius, Marcus: Meditations, Mount Vernon, New York, Peter Pauper

Press, 1957. Bach, G. R.: Intensive Group Psychotherapy, New York, Ronald, 1954. Berne, Eric: A Layman's Guide to Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis, New

York, Simon & Schuster, 1957. (Also Grove Press, 1962.)

: Games People Play, New York, Grove Press, 1964.

: Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy, New York, Grove

224 Suggested Reading

Press, 1961.

Principles of Group Treatment, New York, Oxford, 1966.

Beukenkamp, C: Further developments of the transference life concept in therapeutic groups, J. Hillside Hospital 5:441-448, 1956.

Bion, W. R.: Experience in groups, Human Relations 2:314-320, 1948 (1).

: Ibid., 2:487-496, 1948 (2).

: lbid. t 2:12-22,1949 (3).

: Ibid., 2:295-303, 1949 (4).

: Ibid., 3:3-14, 1950 (5).

: Ibid., 3:395-402, 1950 (6).

: Ibid., 4:221-227, 1951 (7).

: Group dynamics: a re-review, Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 33:235-247,

1952 (8).

•: Experiences in Groups, New York, Basic Books, 1961 (9).

Bohr, Niels: On the notions of causality and complementarity, Science

3:51-54, 1950. Branford, V.: Sociology in Encyclopedia Britannica, 1946. Breasted, James: The Dawn of Conscience, New York, Charles Scribner's

Sons, 1939. Brillouin, L.: Thermodynamics and information theory, Am. Sci. 38:594-

599, 1950. Bronowski, J.: Sci. Amer. 189:140-142, September 1953. Brown, J. F.: Psychology and the Social Order, New York, McGraw-Hill,

1936. Burrow, Trigant: The basis of group analysis, Brit. J. Med. Psychol.

8:198-206, 1928 (1). : Kymographic records of neuromuscular patterns in relation to

behavior disorders, Psychosom. Med. 3:174-186, 1941 (2).

: Neurosis and war, J. Psychol. 22:235-249, 1941 (3).

: The neurodynamics of behavior, Philosophy Sci. 20:271-288,

1943, (4).

—: Phylobiology, Rev. Gen. Semantics 3:265-278, 1946 (5). The social neurosis, Philosophy Sci. 26:25-40, 1949 (6)

Cantril, Hadley: The transactional view in psychological research, Science

220:517-522, 1949. Cartwright, D., and Zander, A.: Group Dynamics, Research and Theory,

Evanston, 111., Row, Peterson & Co., 1953. Confucius: Wisdom of Confucius, edited by Lin Yutang, New York,

Random, 1938. de Montesquieu, C. L.: The Spirit of Laws in World's Great Classics,

New York, Colonial Press, 1900. de Tocqueville, Alexis: Democracy in America in World's Great Classics,

New York Colonial Press, 1900. Engels, Frederick: The Origin of the Family, Chicago, Charles H. Kerr

& Co., 1902. Erikson, E. H.: Childhood and Society, New York, Norton, 1950. Ezriel, Henry: A psycho-analytic approach to group treatment, Brit. J.

Med. Psychol. 23:59-74, 1950 (1). : Some principles of a psycho-analytic method of group treatment,

Proc. First World Cong. Psychiatry, Paris, 1950, 5:239-247, 1952 (2).

: Note on psychoanalytic group therapy: interpretation and

research, Psychiatry 25:119-126,1952 (3). Fabre, J. H.: The life of the Caterpillar, New York, Modern Library,

1925. Foulkes, S. H.: Concerning leadership in group-analytic psychotherapy,

Int. J. Group Psychotherapy 2:319-329, 1951. Foulkes, S. H., and Anthony, E.: Group Psychotherapy, Middlesex, Penguin Books, 1957. Freud, S.: Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, London,

Hogarth Press, 1940. : Totem and taboo in Basic Writing of Sigmund Freud, New York

Modern Library, 1938. Gait, William: The principles of cooperation in behavior, Quart. Rev. Biol.

25:401-410, 1940. Gierke, Otto: Natural Law and the Theory of Society, translated by E.

Barker, Boston, Beacon Press, 1957. Grotjahn, Martin: Psychoanalysis and the Family Neurosis, New York,

Norton, 1960. Hare, P., Borgotta, E., and Bales, R. (eds.): Small Groups, New York,

Knopf, 1955. Hegel, Georg: The Philosophy of History in World's Great Classics, New

York, Colonial Press, 1900. Hitopadesa: Translated by Epiphanius Wilson in World's Great Classics,

New York, Colonial Press, 1900. Jung, C. G.: Psychological Types, New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1946. Klapman, J. W.: Group Psychotherapy, New York, Grune, 1946. Krech, D., and Crutchfield, R. S.: Theory and Problems of Social Psychology, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1948. Lao Tzu: The Way of Life, translated by R. B. Blakney, New York, New

American Library, 1955. Le Bon, Gustav: The Crowd, London, Ernest Benn, 1952. Lombroso, Cesare: The Man of Genius, New York, Charles Scribner's

Sons, 1910. Machiavelli, Niccolo: The Prince and The Discourses, New York, Random,

1940. Moreno, J. L.: Foundations of Sociometry, Sociometry 4:15-35, 1941. Nietzsche, F.: The Philosophy of Nietzsche, New York, Random, 1937. Planck, Max: The meaning and limits of exact science, Science 220:319-

327, 1949. Plato: The Republic, translated by B. Jowett, New York, Random, 1941. Plekhanov, George: The Role of the Individual in History, New York,

International Publishers, 1940. Richter, Curt: Free research versus design research, Science 228:91-93,

1953. Ruderfer, Martin: Action as a measure of living phenomena, Science

220:245-252, 1949. Scheidlinger, Saul: Psychoanalysis and Group Behavior, New York,

Norton, 1952. Sears, Richard, Leadership among patients in group therapy, Int. J. Group

Psychotherapy, 3:191-197, 1953.

226 Suggested Reading

Slavson, S. R.: Analytic Group Psychotherapy, New York, Columbia,

1950. Stewart, J. Q.: The natural sciences applied to social theory, Science

111:500, 1950. Sun Tzu: The Art of War, translated by Lionel Giles in Phillips, T. R.,

(ed.): Roots of Strategy, Harrisburg, Pa., Military Service Publishing

Co., 1940. Syz, Hans: Burrow's differentiation of tensional patterns in relation to

behavior disorders, J. Psychol. 9:153-163, 1940. Trotter, W.: Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War, London, T. F.

Unwin, 1916. Vegetius Renatus, Flavius: De Re Militari, translated by Clarke, J. in

Phillips, T. R., (ed.): Roots of Strategy, Harrisburg, Pa., Military

Services Publishing Co., 1940. von Bertalanffy, L.: The theory of open systems in physics and biology,

Science 222:23-29, 1950. Weaver, Warren: Fundamental questions in science, Sci. Amer. 289:47-51,

September 1953. Weiner, N.: Cybernetics, New York, Wiley, 1948.

/ifrfre*tdix2 fa* Social /ia<yie<pztioK4

Any attempt to evolve a fruitful and comprehensive theory of group dynamics requires a careful definition of the term "group." The first essential is that it distinguish between "groups" and "nongroups." This distinction is rarely made in the literature. In addition, there are almost as many definitions as there are authors in the vast and ever-growing bibliography of the social sciences, which makes it difficult for people to understand each other precisely.*

A concrete example may make it clearer that there are important differences between various kinds of social aggregations. The number of people who may be found on the beach each day between 3 and 4 p.m. in Carmel, California, varies enormously (from fewer than 10 to many hundreds). This variation is strongly influenced by external factors, such as the weather and the season of the year, but has no known connection with the internal social situation in the community, partly because on sunny holidays in the summer by far the majority of beach visitors are from out of town. However, the number of people who attend parties in the same village is influenced only a little by external factors such as the weather and is heavily influenced by the internal social situation. For some years, the writer was "at home" every Sunday evening. No specific invitations were issued, but it was "generally known" that anyone who wished to come was welcome. The attendance at these gatherings corresponded rather closely to a series of appropriate random numbers; one week there would be 2 guests, the next 58, the next 23, and so on.

On the other hand, the writer also conducted three psychotherapy groups over a considerable period in the same village. In these organized groups, it was observed that the attendance was not at all influenced by the weather, nor by the social situation in the village,

* Anything that would improve communication between social scientists should be welcomed. There are not only semantic difficulties, which may be excusable up to a point, but in some cases, studied indifference. For example, there are two major journals devoted to group psychotherapy, (a) The International Journal of Group Psychotherapy and (b) Group Psychotherapy. In the whole volume of (a) for 1953, there are only four references to papers that appeared in (b).

228 A Proposed Classification for Social Aggregations

but mostly by two other factors: unavoidable external accidents and the internal situation of the group itself as perceived by certain individual members. The result was that in spite of considerable differences in the demographies of the groups, there was an almost incredible uniformity in the attendance records. When these three groups were compared with two similar ones held in San Francisco, the uniformities persisted. First, in each of the five groups, the attendance over the life span of the group (8 to 33 months) was 86 per cent plus or minus 3 per cent; secondly, absences due to psychological conflicts involving certain members of each group was 21 per cent plus or minus 3 per cent; thirdly, there was a modal attendance of 100 per cent in each group at 50 per cent plus or minus 8 per cent of meetings; and there were other uniformities.

When the mean attendance of the whole group-series, 88 per cent, was compared with the mean attendance over a period of other organized group-series, an even more surprisingly uniformity emerged. The aggregate attendance records of Kiwanis Clubs in California, Nevada and Hawaii for April, May and June, 1953, was 89.7 per cent; of Rotary Clubs in the United States for October 1952, 87.8 per cent; and of the two public elementary schools and the one high school in Carmel, together with the figures for the neighboring junior college, 89.6 per cent. Thus, the range in all of these group series was only 1.9 per cent and the maximal deviation from the 88.8 per cent mean of these four figures was only 1.0 per cent. These figures have been more fully discussed elsewhere, with some detailed tabulations.*

Whether or not these uniformities will persist within such a small range when a larger set of group-series is studied remains to be seen. Nevertheless, the fact is that attendance at these organized groups had a different quality from attendance at parties and other unorganized meetings. Since the "existence" of all these aggregations depends on the physical presence of the members, the quality of the attendance records cannot be overlooked and is more important than many other factors in determining the dynamics of these congeries.

It is evident that there must be important differences in the alignment of the forces which determine attendance at these three types of social aggregations—the beach, the parties and the organized groups. These differences are of considerable practical import to the traffic officers in the village, to the host who must buy and prepare refreshments and to the leadership of the organized groups (schoolteachers, therapists, etc.) who are trying to accomplish some objective. Experience soon reveals that there are also differences in the

* Berne, E.: Group attendance: clinical and theoretical considerations, Internet. J. Group Psychotherapy 5:392-403, 1955.

atmospheres of these three types of congeries and in the relationships of the people who make them up. Therefore, there are good grounds for questioning the advisability of including them all under the same label (such as "group"). A more discriminating approach, like that used in other sciences, yields a classification of social aggregations that has proved to be of considerable practical and theoretical interest.

The use of such a method distinguishes five types of gatherings as they are found in situ: masses, crowds, parties, groups and organizations. Before these are systematically defined, they will be illustrated by some "dried specimens" whose living counterparts can be found in many communities.

Let each individual in the world be given the simplest possible distinction by assigning him a number. It is convenient to have the numbering begin in Carmel, California, which will be gven a fictitious population of 40. The villagers will be assigned numbers from 01 to 39, the fortieth number, 00, being reserved for the observer. Presumably, there would be no number anywhere greater than 4,000,000,000.

In the first situation, a large number of people, villagers and visitors, are wandering at random (from 00's point of view) on the beach. At any given moment, chosen at random, 00 finds himself lost in this mass of people. It is evident that he will have no way of predicting what company he will find around him, since all meetings take place by chance, at least as far as he is concerned. Under these conditions, he might find that one minute his neighbors consist of 6 visitors and 2 villagers, and a few minutes later it might be just the reverse. At any moment he might find himself standing next to any number whatsoever. This happens to be literally as well as hypothetically true in Carmel because the cosmopolitan Army Language School is situated nearby. The only thing 00 can be certain of is that he is not going to encounter a number over 4,000,000,000.

In the second situation, 00 goes for his mail to the post office at the same hour as many of the other villagers. Since the majority of transients get their mail elsewhere, they do not join this particular crowd, but a few may stray into it due to various circumstances. 00 knows from experience that his neighbors at any given moment on the street leading to the post office at that time of day are more likely to have numbers between 01 and 39 than between 40 and 4,000,-000,000. But he does not know how much more likely; because of continually changing circumstances, there is no sure way of predicting how many visitors will be in town and how many villagers will be out of town on any particular day. Here again, all meetings presumably (says 00) take place by chance, but it can be predicted with a

230 A Proposed Classification for Social Aggregations

degree of confidence based on past experience that there will be more encounters with people of one class (villagers) than with people of all other classes. By actual count, this prediction holds good quite regularly the year round in Carmel between 10:50 and 11:10 a.m. on the block leading to the post office.