Chapter 11

Understanding Leases and Property Valuation

In This Chapter

Looking at leases and their terms

Looking at leases and their terms

Comprehending valuation

Comprehending valuation

Developing value benchmarks

Developing value benchmarks

What you pay for the property and the cash flow it generates make a significant difference in the success of your investment. Leases generate the income stream you should base your real estate investment strategy on. All the quantitative analysis we guide you through in Chapter 12 is for naught if you don’t have a handle on the leases. Therefore, in this chapter, you start your research, analysis, and evaluation of specific properties by analyzing the leases.

We then introduce you to the concepts behind evaluating potential investment properties and explain the key principles behind property valuation that you need to be familiar with. We also provide you with a few quantitative tools you can use to size up prospective properties and determine whether you should move on to other properties or investigate further.

The Importance of Evaluating a Lease

A lease is a contractual obligation between a lessor (landlord) and a lessee (tenant) to transfer the right to exclusive possession and use of certain real property for a defined time period for an agreed consideration (money). A verbal lease can be enforceable, but it’s much better to have a written lease that defines the rights and responsibilities of the landlord and the tenant.

Owning a rental property with attractive and well-maintained buildings may give you a sense of pride of ownership, but what you’re really investing in are the leases. Successful real estate investors know that an excellent opportunity is to find properties with leases that offer upside potential in the form of higher income and/or stability of tenancy.

Owning a rental property with attractive and well-maintained buildings may give you a sense of pride of ownership, but what you’re really investing in are the leases. Successful real estate investors know that an excellent opportunity is to find properties with leases that offer upside potential in the form of higher income and/or stability of tenancy.

Regardless of the type of property you’re considering as an investment, make sure that the seller provides all of the leases. And don’t accept just the first page or a summary of the salient points of the lease — insist on the full and complete lease document along with any addendums or guarantees or written modifications with the seller’s written certification that the document is accurate and valid. (Verbal modifications to the written lease aren’t generally enforceable.) Have your real estate legal advisor review the leases as well (see Chapter 6).

Existing leases almost always run with the property upon transfer of ownership and thus are enforceable. The new owner of the property can’t simply renegotiate or void the current leases he doesn’t like. Because you’re legally obligated for all terms and conditions of current leases if you buy a property, be sure that you thoroughly understand all aspects of the property’s current leases.

Existing leases almost always run with the property upon transfer of ownership and thus are enforceable. The new owner of the property can’t simply renegotiate or void the current leases he doesn’t like. Because you’re legally obligated for all terms and conditions of current leases if you buy a property, be sure that you thoroughly understand all aspects of the property’s current leases.

You may find that you’re presented with the opportunity to purchase properties with leases that are detriments to the property and actually bring down its current and future value. The most common example is a long-term lease at below-market rental rates. But you could also have leases that are so far above the current market conditions that you should discount the likelihood that the leases will be in place and enforceable in the future.

Other common problems with leases include

- The leases are preprinted boilerplate forms (as opposed to a customized lease tailored to the specific tenant-landlord agreement) that may or may not comply with current laws or issues relevant for the specific tenant.

- The charges for late payments, returned checks, or other administrative fees may not be clearly defined or may be unenforceable.

- The rules and regulations may not be comprehensive or enforceable.

- There is no rent escalation clause, which spells out future rent increases, or it isn’t clearly defined.

We’re not saying to bypass purchasing any properties with leases with these problems. Just be aware and factor the effect, if any, into your purchasing decision, or just simply note that you need to change the onerous terms upon renewal.

Reviewing a Lease: What to Look For

A seller should be honest and disclose all material facts about the property he’s selling, but most states don’t have the same written disclosure requirements that are mandated for residential transactions. So even though your broker or sales agent and other members of your due diligence investigation team (see Chapter 6) may be assisting you with inspecting the property and reviewing the books provided during the transaction, remember that you need to be the one who cares the most about your best interests.

Note the expiration dates of the leases, because any lease that’s about to expire should be evaluated based on current market conditions. Future leases may not be at the same rent level, plus you must consider the concessions or tenant improvements necessary to get the lease renewed:

- Residential lease renewals may require a monetary concession or possibly a perk for the tenants, such as cleaning their carpets or installing microwaves or ceiling fans.

- Commercial lease renewals can require significant tenant improvements or rent concessions.

Factor these costs into your analysis because renewing a tenant, even with the associated costs, is typically much more cost effective than losing the tenant. The higher expenses you incur for advertising, screening prospects, and preparing the rental property (cleaning, painting, maintenance, and repairs) plus the loss of income while your rental is vacant are certainly much more expensive than renewing the existing tenant even at a lower rental rate.

Factor these costs into your analysis because renewing a tenant, even with the associated costs, is typically much more cost effective than losing the tenant. The higher expenses you incur for advertising, screening prospects, and preparing the rental property (cleaning, painting, maintenance, and repairs) plus the loss of income while your rental is vacant are certainly much more expensive than renewing the existing tenant even at a lower rental rate.

Comprehending a residential lease

The analysis of current leases for residential properties is usually fairly straightforward, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do your homework! Review each and every residential lease to make sure that no hidden surprises are awaiting you, such as future free rent, limits to rent increases, or promises of new carpet or other expensive upgrades. Some sneaky sellers of residential properties know that some buyers don’t thoroughly review each lease, so they load the leases with future rent concessions in exchange for higher rents up front, which they use to make the property’s financial statements look more desirable. Be sure that you determine the net effective rent and base your offer for a property on those numbers. An apparent above-market lease isn’t really above market if you’re giving away free rent or promising to replace the carpet upon lease renewal.

Making sense of a commercial lease

Commercial leases are much more complicated than residential ones. Thus, the commercial real estate investor must have a thorough understanding of the contractual obligations and duties of the lessor (landlord) and lessee (tenant).

The analysis of commercial leases is typically called lease abstraction. A lease abstract is a written summary of all the significant terms and conditions contained in the lease and is much more than a rent roll. Although a good rent roll covers the lease basics — rent, square footage, length of lease, and renewal date or options — a good abstract covers other key tenant issues such as signage, rights of expansion and contraction, and even restrictions or limitations on leasing to other tenants that offer similar products and services. Have written lease abstracts prepared for any commercial property you’re considering to ensure that you understand all the terms.

The analysis of commercial leases is typically called lease abstraction. A lease abstract is a written summary of all the significant terms and conditions contained in the lease and is much more than a rent roll. Although a good rent roll covers the lease basics — rent, square footage, length of lease, and renewal date or options — a good abstract covers other key tenant issues such as signage, rights of expansion and contraction, and even restrictions or limitations on leasing to other tenants that offer similar products and services. Have written lease abstracts prepared for any commercial property you’re considering to ensure that you understand all the terms.

When obtaining financing for commercial properties, lenders typically require a certified or signed rent roll along with a written lease abstract for each tenant. However, because the income of the property is critical to the owner’s ability to make the debt service obligations, most lenders don’t simply rely on the buyer’s numbers but independently derive their own income projections based on information they require the purchaser to obtain from the tenants. This information includes

-

Lease estoppel: A lease estoppel certificate is a legal document completed by the tenant that outlines the basic terms of his lease agreement and certifies that the lease is valid without any breaches by either the tenant or the landlord at the time it’s executed. These estoppel certificates also benefit the purchaser of the property; you should seriously consider requiring estoppels from all tenants when you purchase a commercial building — regardless of the requirements of any lender.

Although tenant or lease estoppel certificates are rarely required by lenders or purchasers for residential transactions, there is a strong argument that the benefits of the estoppel certificate also apply in the residential setting. Residential tenants are more likely to dispute the amount of the security deposit or claim that they were entitled to unwritten promises by the previous owner — free rent, new carpet, new appliances, extra parking, or waived late charges.

Although tenant or lease estoppel certificates are rarely required by lenders or purchasers for residential transactions, there is a strong argument that the benefits of the estoppel certificate also apply in the residential setting. Residential tenants are more likely to dispute the amount of the security deposit or claim that they were entitled to unwritten promises by the previous owner — free rent, new carpet, new appliances, extra parking, or waived late charges.

-

Financial statements: The rent provided in the lease is a concern, but the amount you actually collect determines the profitability of your real estate investment. Because of this, many leases require the commercial tenant to periodically provide (or present upon request) a recent financial statement and even personal tax returns if the lease is guaranteed.

-

Recent sales info: Most retail leases have provisions for percentage rents, in which the tenant pays a base rent plus additional rent based on a percentage of sales. The percentage rent is often on a sliding scale: The percentage paid by the tenant increases as its sales increase. Be sure that you receive and review recent sales information and ensure that the tenant is current on its percentage rent payments.

Reviewing the financial strength or sales figures for your commercial and retail tenants can be an excellent indicator of the future results of your property. Many of your best tenants in the future will be your small tenants that have successful businesses and need to expand. Also, look at the personal guarantees provided to see whether they’re backed by sufficient resources. The compatibility of the tenant mix is also important. You want your property to have a variety of goods and services that are complimentary and synergistic, which will help your tenants grow and expand their business.

Reviewing the financial strength or sales figures for your commercial and retail tenants can be an excellent indicator of the future results of your property. Many of your best tenants in the future will be your small tenants that have successful businesses and need to expand. Also, look at the personal guarantees provided to see whether they’re backed by sufficient resources. The compatibility of the tenant mix is also important. You want your property to have a variety of goods and services that are complimentary and synergistic, which will help your tenants grow and expand their business.

One of the best ways to make money in real estate is to find commercial leases where the person in charge of the property isn’t collecting the proper rent due under the terms of the lease. For example, you may find that the rent roll from the seller of a property you’re considering for purchase hasn’t implemented rent increases when due. Even more common is the failure of landlords and their property managers to correctly calculate and collect the common area maintenance charges or ancillary fees and reimbursements due from the tenant (see Chapter 12). Of course, you may also find that the landlords are actually overcharging the tenants or there was a one-time insurance reimbursement from a claim, and thus you never want to purchase a property relying on phantom income that you don’t have the legal right to collect.

One of the best ways to make money in real estate is to find commercial leases where the person in charge of the property isn’t collecting the proper rent due under the terms of the lease. For example, you may find that the rent roll from the seller of a property you’re considering for purchase hasn’t implemented rent increases when due. Even more common is the failure of landlords and their property managers to correctly calculate and collect the common area maintenance charges or ancillary fees and reimbursements due from the tenant (see Chapter 12). Of course, you may also find that the landlords are actually overcharging the tenants or there was a one-time insurance reimbursement from a claim, and thus you never want to purchase a property relying on phantom income that you don’t have the legal right to collect.

Understanding the Economic Principles of Property Valuation

Knowing certain economic principles can be useful when seeking to evaluate the current and future value of potential real estate investments. In this section, we supply you with some background information to help you determine which properties are likely to have strong demand.

Have you ever traveled to a foreign country and observed miles of beautiful coastline that you know would be worth a fortune at home? A few years ago, Robert returned from Costa Rica, where he saw dozens of faded “For Sale” signs on mile after mile of unimproved oceanfront property with spectacular water views. Local folks told him that these properties rarely sell and are available at low prices. The weather is humid but not much different than similar weather along the Florida coast, where property is expensive. So what are the factors behind such wide disparities in pricing and value?

Well, you need to consider several important economic principles when evaluating the potential value of a property. The basis of value for any piece of real estate is grounded in the following four concepts:

-

Demand: The need or desire for possession or ownership backed by the financial means or purchasing power to satisfy that need. Having the desire to buy and the ability to buy is effective demand.

-

Utility: The property’s ability to meet a need or satisfy its intended purpose. Various influential factors are location, physical attributes, and governmental regulation, such as zoning or environmental limitations. For example, a very inaccessible location isn’t suitable for a retail property. Amenities or special features of the property or even off-site but in the neighborhood can enhance the utility. This could be an onsite pool or fitness center while proximity to schools, parks, or public transportation in the area can add value.

-

Scarcity: Scarcity refers to the relative demand versus the relative supply of a specific type of property. For example, there is high demand and relatively low supply of coastal land in California, yet there is low demand and abundant supply of California desert land between Los Angeles and Las Vegas. Hence, coastal land with limited supply and high demand is scarcer and has higher value. Properties are unique and finite, and the concept of substitution doesn’t apply unless another property can meet the same needs. Substitution is the idea that an investor won’t pay more for a property than the price of another, similar property.

-

Transferability: This term refers to the relative ease with which ownership rights are transferred from one owner to another and the rights associated with the ownership and control of a given property. It also includes the ability for private parties to own and control real estate, which generally isn’t a problem in the United States, but would be a major factor for real estate investors seeking to invest internationally.

Value can also be affected when certain restrictions (such as the association conditions, covenants, and restrictions found in most homeowners associations) are elements of utility while also being part of transferability because they run with the land and limit the rights of future owners.

In the earlier example, the oceanfront land in Costa Rica wasn’t in high demand, was relatively inaccessible (the closet major airport was in the capital city of San Jose — nearly 100 miles away), the availability of so many similar properties made the scarcity a nonissue, and the complications of the government requirements for foreign ownership may limit the ability to transfer the property to non–Costa Ricans.

An understanding of the current value and future potential of real estate investments is based on these four concepts. But three other important economic principles can affect the value of real estate now and in the future:

-

Regression: A property’s value is negatively impacted by surrounding properties that are inferior, of lower value, or in worse condition. In other words, don’t buy the best property in a bad neighborhood.

-

Progression: A property’s value is positively impacted by surrounding properties that are superior, in better condition, and have a higher value.

This concept is one of the most important for the real estate investor looking for long-term success. Seek a well-built but neglected and poorly maintained property located in a good neighborhood. You then add significant value by repositioning the property up to the level of the surrounding properties through proper maintenance, repairs, and upgrades.

This concept is one of the most important for the real estate investor looking for long-term success. Seek a well-built but neglected and poorly maintained property located in a good neighborhood. You then add significant value by repositioning the property up to the level of the surrounding properties through proper maintenance, repairs, and upgrades.

-

Conformity: Property values are optimized when a property generally conforms to the surrounding properties, and negatively impacted when it doesn’t. Higher or optimized value through conformity is what you’re seeking when you purchase the distressed property and renovate it to enhance its appearance and utility. This is also the economic principle that cautions against overimproving the property.

Determining highest and best use

All of these economic principles are based on the premise that the maximum value of real estate is achieved when a property is being utilized in its highest and best use. Highest and best use is the fundamental concept that there is one single use that results in the maximum profitability by the best and most efficient use of the property. (This concept focuses solely on financial issues. For example, it says nothing about the impact that a significant, dense property development has on traffic and the local environment.)

The highest and best use of a specific property doesn’t remain constant over time. Zoning of a property can eliminate certain possible uses of a property at the time of evaluation. However, particularly for properties in the path of progress, time can create new opportunities. For example, agricultural land in the middle of a rapidly expanding commercial and resort area isn’t the highest and best use (financially speaking) of the property. (Check out Chapter 10 for more on zoning issues.)

This was the case for the strawberry fields that bordered the west side of Disneyland in Anaheim for several decades. The long-time owner of the property wasn’t interested in selling at any price, so the property wasn’t utilized to its highest and best use. However, after the owner passed away, his heirs quickly sold the property, and the Disney resort developed the property.

Comparing fair market value and investment value

When discussing real estate values, most people immediately think of fair market value — basically, the price that the buyer and seller can agree to for a real estate transaction. Determining the fair market value of real estate often seems like an elusive concept much like the old adage “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

A bit more specifically, the fair market value is the most likely price a buyer is willing to pay and a seller is willing to accept for a property at a given time. This definition is based on three assumptions:

- The market for similar real estate is open and competitive.

- The buyer and seller are both motivated, acting prudently and with knowledge.

- The buyer and seller aren’t under any undue influence or affected by unusual circumstances.

However, real estate investors encounter another type of value — investment value. Although the market value is the value of a property to a typical investor, investment value is its value to a specific investor based on his particular requirements, such as the cost of capital, tax rate, or personal goals.

Someday, you may find yourself competing against another buyer for a prime investment property only to be surprised that she seems willing to pay much more. If you’ve carefully analyzed the property, and the seller provided the same information about the property to all potential purchasers, the other buyer is likely basing her offer on the property’s investment value to her.

Maybe the other buyer needs a replacement property for a 1031 exchange and has the strong motivation of potentially losing the deferral of significant capital gains unless she buys property of equal or greater value within certain defined time periods (see Chapter 18). Such buyers are often willing to pay a premium for a property to avoid losing the tax deferral benefits available under federal and many state tax codes.

You don’t want to get into a bidding war for a property and overpay, so remember that fair market value and investment value are two different concepts. Investment value can be higher or lower than market value. For example, an investor who can’t use the tax benefits of depreciation would be willing to pay less for a property that would generate large annual depreciation than would an investor that has other passive income and can use the deferral of taxation to reduce his current income tax obligations.

You don’t want to get into a bidding war for a property and overpay, so remember that fair market value and investment value are two different concepts. Investment value can be higher or lower than market value. For example, an investor who can’t use the tax benefits of depreciation would be willing to pay less for a property that would generate large annual depreciation than would an investor that has other passive income and can use the deferral of taxation to reduce his current income tax obligations.

Reviewing the Sources of Property-Valuing Information

As a prospective buyer, you may find that quite a few folks have an idea of what a piece of property is worth:

-

Professional appraisers: Owners and lenders hire these property valuation specialists to formulate the value of a property at a given point in time. Sellers rarely consult appraisers unless the sale is the result of litigation or probate, or a government entity is the buyer or seller.

-

Brokers and agents: A Competitive Market Analysis (CMA) or the similar but more in-depth Broker Price Opinion (BPO) is an estimate of market value that is generally available from brokers or agents active in the local area where the property is located. Some lenders also use the term Broker Opinion of Value (BOV). Because brokers and agents routinely track the listing and sale of comparable properties, they offer this information to owners with the goal of getting a listing on the property. Their valuation may be fair and reasonable; however, a buyer should remember that the real estate agent isn’t a disinterested third party, but rather only paid if he’s involved in a sales transaction — and then he’s compensated more for a higher sales price.

-

Sellers: Many sellers also do their own informal or anecdotal research by obtaining information about recent sales of properties they know in the area. Ultimately, the seller must make the final critical decision as to the asking price for a property. Because the valuation of real estate has many variables, inefficiencies in the pricing of income properties are common.

As a prospective buyer, the values these folks come up with are merely starting points for your analysis. Much more research is required. We spend the balance of this chapter, and Chapter 12, helping you do your research.

Many real estate investors find that becoming real estate appraisers can be helpful to their success in investing in real estate. You may want to get a certification in real estate appraisal while making your real estate investments. Another benefit of this choice is that you qualify for the favorable tax treatments offered to real estate professionals (as we describe more in Chapter 18). Or you may just want to have a better understanding of the techniques used by appraisers for evaluating your own properties. For more information on professional appraisers and their education and training, please refer to

Many real estate investors find that becoming real estate appraisers can be helpful to their success in investing in real estate. You may want to get a certification in real estate appraisal while making your real estate investments. Another benefit of this choice is that you qualify for the favorable tax treatments offered to real estate professionals (as we describe more in Chapter 18). Or you may just want to have a better understanding of the techniques used by appraisers for evaluating your own properties. For more information on professional appraisers and their education and training, please refer to

www.appraisalfoundation.org or

www.appraisalinstitute.org.

Establishing Value Benchmarks

The proper analysis of real estate requires due diligence and research, which starts with evaluating the existing leases (see the “The Importance of Evaluating a Lease” section earlier in this chapter) and continues with crunching the numbers (refer to Chapter 12). However, almost more than any other investment, the real estate industry has relied for years on value benchmarks to set prices and evaluate potential purchases.

One of the reasons value benchmarks are so widely used is that they can easily be calculated by using basic information available on a property. Virtually all properties you encounter for sale include this information in the listing brochures or offering packages provided by sellers or their brokers or sales agents.

These value benchmarks are general guidelines only, and they can be misleading, especially to the novice real estate investor. When you first hear them, they sound impressive, but they’re only quick and simple indicators of value. Don’t make investment decisions without calculating the Net Operating Income (NOI), which we cover in detail in Chapter 12. The measures in this section shouldn’t be the sole basis for the purchase of income-producing real estate.

These value benchmarks are general guidelines only, and they can be misleading, especially to the novice real estate investor. When you first hear them, they sound impressive, but they’re only quick and simple indicators of value. Don’t make investment decisions without calculating the Net Operating Income (NOI), which we cover in detail in Chapter 12. The measures in this section shouldn’t be the sole basis for the purchase of income-producing real estate.

Some professional appraisers may perform these calculations as a verification test to ensure that their results are in the ballpark and even include them in their appraisal. However, these numbers aren’t as accurate at indicating value as the traditional methods of appraising the value of real estate (the cost approach, market data approach, and income capitalization approach discussed in Chapter 12). Neither are they formally recognized and mandated by the professional appraisal institutes or federal lending guidelines as approved methods of appraising real estate.

In the following sections, we cover the standard value benchmarks that apply to all types of real estate, as well as some that are unique to a specific sector.

Gross rent/income multiplier

Two important value benchmarks include

-

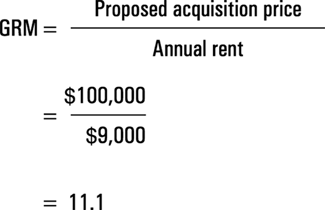

Gross Rent Multiplier (GRM): GRM is most commonly used for residential income properties, such as single-family rental homes and small apartment buildings, because virtually all of their income is in the form of rent payments from tenants.

-

Gross Income Multiplier (GIM): GIM includes rent plus all other sources of income and therefore is more widely used to quickly evaluate commercial or industrial real estate investments.

The monthly rent or income is used in some areas of the country, but typically the GRM and GIM are calculated by using annual numbers. Both the GRM and GIM are calculated by dividing the proposed acquisition price by the annual rent or total income. For example, the GRM for a rental home that can be acquired for $100,000 with a monthly rent of $750 ($9,000 annualized):

Likewise, an industrial building that sells for $250,000 with an annual gross income of $20,000 has a GIM of 12.5.

These formulas require little information and are a simple way to quickly compare similar properties. Savvy real estate investors glance at the GRM or GIM on a listing sheet and may either eliminate some properties from or earmark them for further consideration, but they don’t write an offer to purchase just because the ratio seems attractive. Experienced investors know that much more analysis is needed because these formulas don’t consider future appreciation, financial leverage, the risk of the investment, or operating expenses. They focus on gross income only, which can be deceptive.

These formulas require little information and are a simple way to quickly compare similar properties. Savvy real estate investors glance at the GRM or GIM on a listing sheet and may either eliminate some properties from or earmark them for further consideration, but they don’t write an offer to purchase just because the ratio seems attractive. Experienced investors know that much more analysis is needed because these formulas don’t consider future appreciation, financial leverage, the risk of the investment, or operating expenses. They focus on gross income only, which can be deceptive.

Here’s how relying on these formulas can be tricky: If the GRM and GIM ratios seem high, you need to check further to see whether the price is too high — in which case you should pass on this property. Or maybe the rents are below market value and the price is reasonable. Conversely, you may see a low GRM and think that you found your next investment prospect only to discover that the property is really overpriced because the seller has projected unrealistic rents based on seasonal rentals for dilapidated furnished studio apartments in a beach community.

Because both GRM and GIM only consider the income side of the investment, these formulas don’t differentiate between the operating and capital expense levels of each property. The income is important, but what you’re left with after paying the expenses makes your mortgage payment and provides you with cash flow. As we discuss in Chapter 12, the operating and capital expense levels can make a tremendous difference in the overall cash flow and the value of the property.

For example, compare two small apartment communities — both available for $1 million and each with an annual gross income of $100,000. On each, the GRM is 10. But which is the better investment? The GRM doesn’t give any indication, but further analysis gives you the answer because expenses for each property probably differ.

One apartment building is more than 40 years old and has only month-to-month rental agreements with a high turnover of tenants. The property has interior hallways, is poorly maintained, and has an elevator that has never been modernized. This property suffers from above-average annual operating expenses of $85,000. The other potential investment is also an older property but caters to seniors on long-term leases who rarely move and do little damage. The building is a two-story, garden-style walk-up with annual expenses of $45,000. Clearly, assuming you use the same financing for each property, the second property (with $40,000 less in expenses) should result in greater cash flow to the owner.

Price per unit and square foot

For apartment investors, the asking price per unit can provide a general feel for the reasonableness of the seller’s pricing. Price per unit is calculated by simply dividing the asking price by the number of units. For example, a six-unit building priced at $240,000 works out to $40,000 per unit.

Like the GRM calculation, the price per unit does have its limitations. The calculation doesn’t account for the location or age of the property, the quality of construction or amenities, or the size and condition of the units. You should only use it as a quick indicator of relative value when comparing similar properties in the same market area.

The price per square foot is a widely used yet simple calculation most often associated with commercial, industrial, and retail properties (and sometimes used for residential properties). To find this number, take the asking or sales price of a property and divide it by the square footage of the buildings. It’s only a ballpark gauge of relative value and can be limited because it doesn’t factor in the location or quality of the improvements or other important issues like the parking ratio or the occupancy level and rent collections.

For example, a 5,000-square-foot building going for $250,000 may seem like a good value at $50 per square foot in your market until you find that it hasn’t been occupied for years and is in a distressed area of town. Or a 10,000-square-foot building for $1.25 million may seem overpriced at $125 per square foot until you discover that the U.S. Postal Service just signed a 20-year net lease at full market rent with generous annual cost-of-living increases.

Replacement cost

Replacement cost is another factor that real estate investors should consider prior to making a real estate investment. The replacement cost is the current cost to construct a comparable property that serves the same purpose or function as the original property. The calculation of replacement cost is usually done by comparing the price per square foot to an estimate of the cost per square foot to build a similar new property, including the cost of the land.

If you buy an investment property below its replacement cost, you can generally know that a prudent builder probably won’t construct a similar new product. This fact minimizes the chance that overbuilding will result in excess supply. It isn’t until resale value (minus depreciation) of existing properties equals the cost to construct new properties that a builder will find it financially feasible to build an additional product.

If you buy an investment property below its replacement cost, you can generally know that a prudent builder probably won’t construct a similar new product. This fact minimizes the chance that overbuilding will result in excess supply. It isn’t until resale value (minus depreciation) of existing properties equals the cost to construct new properties that a builder will find it financially feasible to build an additional product.

Especially when considering investing in a real estate market that seems overpriced, avoid buying investment properties where the cost for new construction is equal to or lower than the replacement cost of a similar building. When prices rise to the point that it’s more economical to build a new product rather than buy existing investment properties, builders know that they can build an additional product and sell it at a profit. And you will then have additional properties to compete with.

Looking at leases and their terms

Looking at leases and their terms Comprehending valuation

Comprehending valuation Developing value benchmarks

Developing value benchmarks Owning a rental property with attractive and well-maintained buildings may give you a sense of pride of ownership, but what you’re really investing in are the leases. Successful real estate investors know that an excellent opportunity is to find properties with leases that offer upside potential in the form of higher income and/or stability of tenancy.

Owning a rental property with attractive and well-maintained buildings may give you a sense of pride of ownership, but what you’re really investing in are the leases. Successful real estate investors know that an excellent opportunity is to find properties with leases that offer upside potential in the form of higher income and/or stability of tenancy. Existing leases almost always run with the property upon transfer of ownership and thus are enforceable. The new owner of the property can’t simply renegotiate or void the current leases he doesn’t like. Because you’re legally obligated for all terms and conditions of current leases if you buy a property, be sure that you thoroughly understand all aspects of the property’s current leases.

Existing leases almost always run with the property upon transfer of ownership and thus are enforceable. The new owner of the property can’t simply renegotiate or void the current leases he doesn’t like. Because you’re legally obligated for all terms and conditions of current leases if you buy a property, be sure that you thoroughly understand all aspects of the property’s current leases. You don’t want to get into a bidding war for a property and overpay, so remember that fair market value and investment value are two different concepts. Investment value can be higher or lower than market value. For example, an investor who can’t use the tax benefits of depreciation would be willing to pay less for a property that would generate large annual depreciation than would an investor that has other passive income and can use the deferral of taxation to reduce his current income tax obligations.

You don’t want to get into a bidding war for a property and overpay, so remember that fair market value and investment value are two different concepts. Investment value can be higher or lower than market value. For example, an investor who can’t use the tax benefits of depreciation would be willing to pay less for a property that would generate large annual depreciation than would an investor that has other passive income and can use the deferral of taxation to reduce his current income tax obligations.