In the whole Northwest region many roads are impassable during the rainy summer season (approximately Christmas to Easter). Fall and spring (Apr–May and Sept–Nov) are the best times for a visit.

The Northwest

This is where Argentina’s colonial and indigenous cultures collide and mingle, amid some of the country’s most magnificent and diverse landscapes.

Main Attractions

With the possible exception of Buenos Aires, no region of Argentina is easier to fall in love with than the country’s Northwest. Taken together, its colonial and pre-colonial heritage, friendly locals, hallucinatory rock formations, increasingly sophisticated tourism infrastructure, and lush valleys that rise into oxygen-thin, condor-haunted uplands are a brew that most travelers find intoxicating. It doesn’t hurt that the region – Salta and Jujuy in particular – is extremely compact, with most places of interest within a few hours of one other. (For those who have experienced the rigors of Patagonia, where getting from one place to the next can take days, it is hard to overstate what a relief this can be.)

The Northwest comprises the provinces of Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago del Estero, and Catamarca, and can be (crudely) divided into the three discrete ecosystems. First, the quebradas: the arid, high precordillera (foothills of the Andes), characterized by multicolored desert hillsides, cacti and dry shrubs, deep canyons, and wide valleys. In stark contrast, the yungas, or subtropical mountainous jungle, are identified by dense vegetation, misty hillsides, and trees draped in vines and moss. Finally, there is the puna: cold, high-altitude and practically barren plateaux close to the Chilean and Bolivian borders.

Salinas Grandes salt flat.

Yadid Levy

The majority of tourists base themselves in or around Salta, the capital city of the province of the same name and an attractive destination in its own right. From here, either with a rental car (by far the best option) or on organized excursions, one can explore the Valles Calchaquíes (Calchaquí Valleys), named for one of the pre-Inca tribes that settled the region, which occupy a 17,500-sq-km (6,800-sq-mile) area in the provinces of Salta, Catamarca, and Tucumán, and the Quebrada de Humahuaca, a stunning mountain valley that cuts north through Jujuy towards the Bolivian border. More adventurous travelers, or those with plenty of time on their hands, can strike out onto the less-beaten tracks of Catamarca and Tucumán.

TIP

There are interesting yet modest ruins scattered throughout the Northwest, historical museums and monuments, traditional foods and music, and arts and crafts still made using ancient techniques. This is the most traditional region of Argentina, and the area where the size and influence of the indigenous population are still significant.

Iglesia y Convento de San Francisco.

Yadid Levy

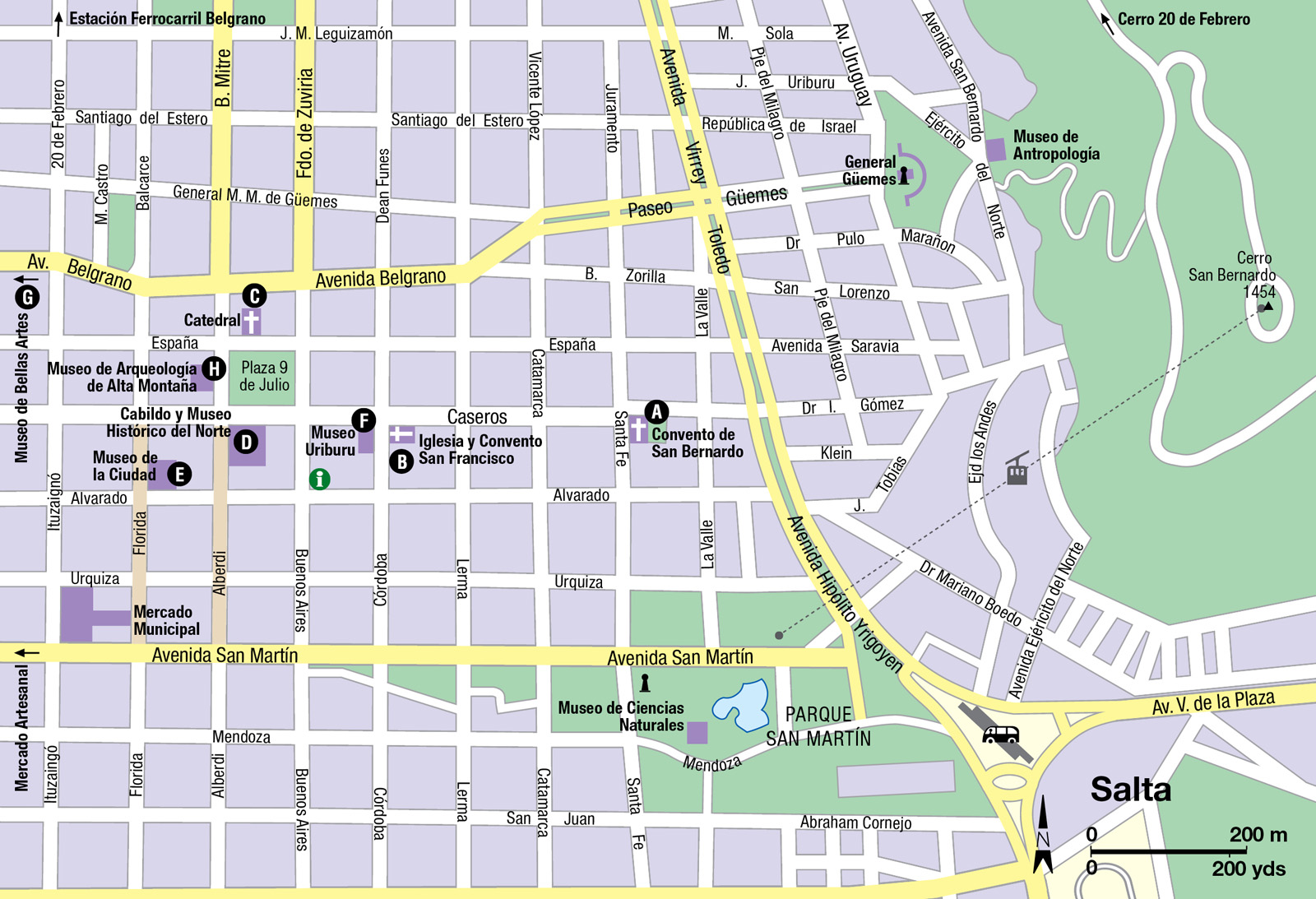

Salta la Linda

Salta 1 [map], also known as “Salta la Linda” or “Salta the Beautiful,” is probably the most seductive town of the Northwest, due both to its setting in the lovely Lerma Valley and to the eye-catching contrast of its old colonial buildings with its modern urban architecture. The inhabitants are very proud – some might say snobbish – of the city’s colonial heritage, and many salteños (as they are known) consider themselves to be the only true criollos (native Argentines of Spanish descent) “untainted” by generations of immigrants. The city is the most formal in dress and behavior in the region, and is the largest in northern Argentina, making it a good base to explore the area, which offers many opportunities for adventure tourism.

TIP

An excellent way to pass an evening in Salta is at a local peña, where traditional food is served and folk music is performed live by local musicians. Among the city’s best places are El Boliche de Balderrama (Av. San Martín 1126) and La Casona del Molino (Luis Burela and Caseros 2500).

Founded in 1582, Salta was an important colonial settlement and several of the most important buildings raised during the era of Spanish rule have survived. One of these is the Convento de San Bernardo A [map] at Caseros and Santa Fe, established in 1582 (the current structure dates from 1723). Its bright-white adobe walls debar all but the Carmelite nuns who live here, though you can admire the door that indigenous craftsmen carved from carob wood in 1762. (You can also visit the adjoining church for early morning Mass.) Three blocks west is the celebrated Iglesia y Convento de San Francisco B [map], which seems to grace the glossy side of every other postcard sold in Salta. Built in the late 16th century, it’s as exuberant as the Convento de San Bernardo is plain, though the ravishing red and gold terracotta facade that makes it so was only added in the 19th century, along with the 54m (117ft) -high bell tower.

Quechua girls in Humahuaca.

Yadid Levy

Several important buildings surround Salta’s main square, Plaza 9 de Julio. The Catedral Basílica de Salta C [map], on the north side, is an Italianate construction built between 1858 and 1882. It houses the remains of independence heroes such as General Martín Miguel de Güemes. Opposite the cathedral on the plaza is the Cabildo y Museo Histórico del Norte D [map] (Tue–Fri 9.30am–1.30pm and 3.30–8.30pm; charge), dating from 1626 (the current structure was completed in the 1780s), which used to house the government of the viceroyalty until 1825. It was the seat of provincial government until the end of the 19th century. With its graceful double portico, the Cabildo is particularly famous for the 16th-century statues of the Virgin Mary and Cristo del Milagro (Christ of the Miracle), washed up from a Spanish shipwreck on the Peruvian coast and credited with having performed miracles such as stopping a 1692 earthquake. The statues are paraded in a colorful procession every September 15. The Cabildo also houses a very fine historical museum, which has 10 rooms of archeological and colonial artifacts, including oil paintings and several impressive Baroque wooden pulpits.

TIP

In spite of its relatively cool mountain climate, most businesses in the Northwest retain the siesta custom inherited from Spain, and close from noon until about 5pm, although this is often offset by longer opening hours in the evening. Supermarkets, however, may stay open all day.

Museums and mummies

Two blocks from the Cabildo, on the corner of Florida and Alvarado, is the Museo de la Ciudad E [map] (Mon–Fri 8.30am–1pm and 4–8pm, Sat 9am–1pm), dating from 1870 and once the residence of the Hernández family. It now houses the museum of the city of Salta.

Another residence from the colonial period, the Museo Uriburu F [map] (Tue–Sun; charge), located on Caseros one block from San Francisco, has been renovated and houses a museum of the colonial era. Also in this area are a number of artisans’ shops, primarily selling silver and alpaca products of high quality (the locally crafted silver, alpaca, and wooden mate holders are especially beautiful).

A few blocks southeast of the Plaza 9 de Julio is the large Parque San Martín, which includes a statue by famous Tucumán sculptress Lola Mora; and at Mendoza 2, the Museo de Ciencias Naturales (daily; charge) has exhibits of native plant and animal life from Salta and Jujuy, including examples of the tatú, a local type of armadillo, and of fossils of earlier fish and plant species.

The art collection at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Salta G [map] (Mon–Fri 9am–2pm, Sat 11am–7pm; charge) was first exhibited in 1930. It has lived in various locations since then, moving to its current home, a French-style building from the early 20th century known as Casa Usandivaras (Avenida Belgrano 992), in 2008. The house has been restored, and the museum has a fine collection of American art, in particular from local and Argentine artists, as well as paintings from the Jesuit missions.

Salta city.

Yadid Levy

The Museo de Antropología (Mon–Fri 8am–7pm, Sat 10am–6pm; free), on Ejército del Norte and Polo Sur, contains a chronology of the cultural history of the Northwest and, in particular, an exhibition of pieces from Santa Rosa de Tastil, including weavings and a stone on which the “Tastil dancer” was carved. More impressive is the Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña H [map] (MAAM; Tue–Sun 11am–7.30pm) at Mitre 77, which opened in 2004. The information panels and artifacts relating to Andean and Inca culture are interesting but most visitors come to see the museum’s raison d’être, which is the storage and display of the mummified remains of the so-called Niños de Llullaillaco or Children of Llullaillaco. The bodies of these children – six, seven, and fifteen years of age when they died – were discovered in 1999, near the summit of the Llullaillaco volcano in the Andean cordillera. Perfectly preserved by the extreme cold, the corpses have been studied exhaustively by anthropologists who have concluded that the children were sacrificed in a religious ritual 500 years ago, when the Inca empire ruled northwest Argentina. Only one mummy is on display at any one time, and the museum has taken pains to ensure to the atmosphere surrounding the exhibit is one of dignity and respect. The experience is fascinating and moving, and to some, disturbing.

Also well worth a visit is the Mercado Artesanal (daily 8am–8pm), three blocks southwest of the Plaza 9 de Julio, with handicrafts by some of the indigenous tribes living in the vast province of Salta.

A superb view of the city can be enjoyed from atop Cerro San Bernardo, which can be reached by cable car from Parque San Martín; the cable car runs daily 10am–7pm.

Tren a las Nubes on La Polvorilla viaduct.

Dr.Haus

Train to the Clouds

The Tren a las Nubes (Train to the Clouds), the third highest working railway line in the world, is now run purely for tourists. As well as being one of the highlights of Argentina, it is also one of the last remaining “great railway journeys” of South America. The train, fully equipped with dining car, bar, guide, and stewardess, leaves Salta’s main station at 7am and enters the deep Quebrada del Toro gorge about an hour later. Slowly, the train starts to make its way up. The line is a true work of engineering art, and doesn’t make use of cogs, even for the steepest parts of the climb. Instead, the rails have been laid so as to allow circulation by means of switchbacks and spirals. This, together with some truly spectacular scenery, is what makes the trip so fascinating.

After passing through San Antonio de los Cobres, the old capital of the former national territory, Los Andes, the train finally comes to a halt at La Polvorilla Viaduct (63 meters/207ft high and 224 meters/739ft long), an impressive steel span amid the breathtaking Andean landscape. At this point the train has reached an altitude of 4,197 meters (13,850ft) above sea level. From here the train returns to Salta, where it arrives in the late evening, after a roundtrip of 272km (169 miles), taking about 14 hours.

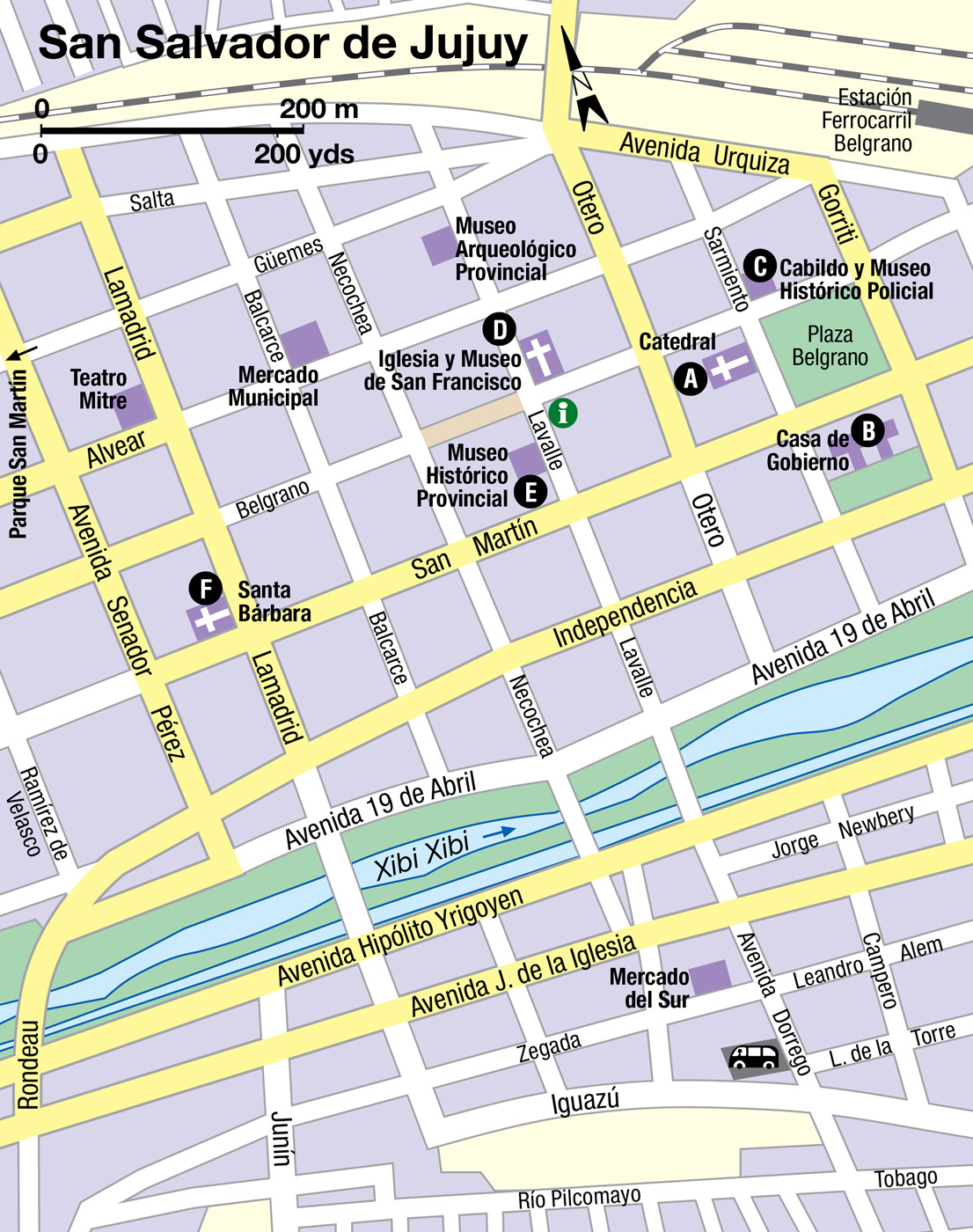

North to Jujuy

From Salta, a winding but wonderful mountain road, La Cornisa, takes you, in about an hour and a half, to San Salvador de Jujuy 2 [map]. Don’t miss the extraordinary gilded pulpit in the catedral A [map] (daily). Carved from cedar and ñandubay wood by indigenous craftsmen, it is the most important colonial-era artifact of its kind in the country. The cathedral dates from 1611, although most of the current building was completed in 1765 after being destroyed by an earthquake late in the 17th century. In addition to the famous pulpit, the cathedral has a beautiful chapel dedicated to the Virgin of the Rosary, as well as an outstanding 18th-century painting of the Virgin Mary. The tourist office is located nearby in the old railway station.

Locally made carpets of llama and alpaca wool on sale at Purmamarca’s market.

Yadid Levy

Among the other attractions of this colonial city are the Casa de Gobierno B [map], across the Plaza General Belgrano from the cathedral. The classical building, completed in 1920, houses the first Argentine flag and coat of arms, created by independence hero General Belgrano and donated to the city in 1813. The Salón de la Bandera, where the flag is on display, is open Mon–Fri 8am–noon and 4–8pm. The front of the Casa de Gobierno has four statues, representing Peace, Liberty, Justice, and Progress, by Lola Mora, the Tucumán artist who was once director of plazas and parks in Jujuy. Facing the Casa de Gobierno is the Cabildo y Museo Histórico Policial C [map], a 19th-century building reconstructed after it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1863. The Cabildo houses the city’s police department and a small museum (daily 8.30am–1pm and 3–9pm; free), which includes exhibits on the police’s anti-drugs campaign.

Two blocks from the Cabildo, on Belgrano and Lavalle, is the beautiful Iglesia de San Francisco D [map] (daily 6.30am–noon and 5.30–9pm), situated on the site since the beginning of the 17th century, although the current building, maintaining the traditional style of Franciscan churches, dates from the 1920s. The church has a famous pulpit carved on the basis of traditional designs from Cusco in Peru and a notable wooden statue of St Francis – known locally as San Roque. Within the church is the Museo de San Francisco (daily 8am–noon and 5–8.30pm), whose exhibits include Stations of the Cross painted in Bolivia in 1780.

The local religious imagery is particularly notable for its rather gory nature, primarily because life for the indigenous communities who originally inhabited the area was so hard that early missionaries had to depict the sufferings of Christ and other religious figures in exceptionally horrific terms in order to make an impression on the locals. Statues in particular are prone to depict gaping and bloody wounds with more enthusiasm than is usually the case.

Among the other interesting museums in Jujuy are the Museo Histórico Provincial E [map] at Lavalle 256 (Mon–Fri 8am–8pm, Sat–Sun 9am–1pm and 4–8pm; charge), located in a 19th-century residence in which the hero of the Argentine union, General Lavalle, died in 1841 after his defeat by the federalists at the battle of Famaillá. The museum contains exhibits of 19th-century dress, as well as religious works of art, and a room is dedicated to the independence movement, including weapons captured in the battle of Suipacha.

Two blocks away, also on Lavalle, is the Museo Arqueológico Provincial (daily 9am–noon and 3–9pm; charge), where exhibits, including stone, ceramic, and metal objects, from the region are on display. The oldest church in Jujuy is Capilla de Santa Bárbara F [map] dating from 1777 and including a collection of 18th-century religious paintings. Two blocks away, on Calle Lamadrid, is the Teatro Mitre, constructed in 1901. The Italian-style theater was restored in 1979. Two blocks to the east is the Mercado Municipal. The French-style railway station is located two blocks from the Plaza Belgrano, on Gorriti and Urquiza, while the bus terminal is a few blocks south of the Río Chico Xibi Xibi at the corner of Iguazú and Dorrego.

TIP

A pleasant walk in the northern outskirts of Jujuy is to the road (Avenida Fascio) by the Río Grande, where some of the oldest and grandest homes in the city are located, often with courtyards and ornate window grates.

Jujuy’s park and Termas de Reyes

Several blocks to the west of the plaza is the Parque San Martín, the city’s only park, which, although smaller than those of other Argentine cities, contains a swimming pool as well as a housing complex and a restaurant. Near to the park, on Bolivia 2365, is the Museo de Mineralogía (Mon–Fri 9am–1pm), which belongs to the provincial university’s geology and mining faculty. The museum includes exhibits of the mineral wealth of the province, detailing the history of its tin- and iron-mining tradition as well as its gold deposits.

A few miles from town, one can visit the Termas de Reyes spa, located in a narrow valley. The visit offers beautiful views of the city and of mountains and lakes in the area, as well as the opportunity to indulge in thermal bathing. Nearby is the Parque Provincial Potrero de Yala, a quiet spot amid the lakes much favored by residents of the city.

View over the town of Maimara and the Paleta del Pintor (Painter’s Palette) hills in the Quebrada de Humahuaca.

Yadid Levy

The colorful Quebrada

North of San Salvador de Jujuy, RN9 climbs steadily up, and before long the sun breaks through. Here, a wide and highly distinctive quebrada (gorge) is dominated by the Río Grande. This river receives torrential and often destructive rains in the summer, when the colors of the valley wall become more intense and delineated. The Quebrada de Humahuaca valley has been used for 10,000 years as an important passage for transporting both people and ideas between the Andean highlands and the plains of Jujuy below. In 2003 it was made a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Purmamarca 3 [map], which means “Desert Region” in the Quechua tongue, is a tiny village 65km (40 miles) north of San Salvador de Jujuy. The adobe and cactus-wood church in the central plaza dates from the mid-17th century, but most visitors to Purmamarca are here to see – and to photograph – a landmark that was here many millions of years before: the Cerro de los Siete Colores (Hill of the Seven Colors). Those celebrated hues – yellow, orange, red, pink, gray, green, and black – were created by marine sediments that accumulated in the rock strata over eons. If time allows, you can hike around the hill following a well-defined trail.

The next stop after Purmamarca is Tilcara 4 [map], some 20km (12 miles) north. With around 6,000 inhabitants, Tilcara is a proper town and can date its origins back to the pre-Inca era. You can find out more about the area’s pre-colonial history at the Museo Arqueológico Dr Eduardo Casanova (Belgrano 445; tel: 0388-4955 006; daily 9am–6pm; charge), whose exhibits include some Inca masks, a pre-Inca mummy, and some fine ceramics. Keep your ticket because it also gets you entry to the Pucará de Tilcara, a 1,000-year-old ruined fort a couple of kilometers out of town. The fort was discovered in 1908 and reconstructed in the 1960s. Next to the fort is a botanical garden, with specimens from the puna (high plateau).

Propping up a restaurant doorway whilst drinking mate.

Yadid Levy

At El Angosto de Perchel the quebrada narrows to less than 200 meters (650ft) and then opens into a large valley. Wherever the available water is used for irrigation, tiny fields and orchards give a touch of fresh green to the red and yellow shades of the river banks.

The heights of Humahuaca

Further up the valley lies the town of Humahuaca 5 [map], which gives its name to the whole gorge. Previously an important railway stopover on the way up to Bolivia, it has suffered badly from the closure of the railway. Humahuaca lies at almost 3,000 meters (9,000ft), so move very slowly to avoid running out of breath. Also avoid eating heavily or drinking alcohol prior to ascending: a cup of sweet tea is more beneficial at this altitude. Here one finds stone-paved and extremely narrow streets, vendors of herbs and produce near the former railway station, and an imposing monument made from 70 tonnes of bronze commemorating the Argentine War of Independence. The town’s church, Nuestra Señora de la Candelaría, dates back to the 16th century. The museum of local customs and traditions is also worth a visit. Humahuaca’s top tourist attraction, however, is a life-sized mechanized saint (St Francis Solanus) that emerges from the Cabildo’s clock tower each day at noon. Pilgrims gather below to witness this low-tech apparition.

Humahuaca.

Yadid Levy

Most travelers pay only a short visit to Humahuaca, but a stay of several days is truly worthwhile, as many side trips can be made from here. Some 9km (6 miles) outside the town are the extensive archeological ruins of Coctaca. The true significance of this site is still largely unknown although scientists are studying it, and its secrets may soon be revealed. Other options include a journey to Iruya, a hamlet (1,000 inhabitants) of narrow streets and colonial-era buildings cradled amid towering mountains, 75km (47 miles) from Humahuaca. The only way to get there is via RP19, a zigzagging unpaved road that branches off from RN9 25km north of Humahuaca and then passes over the spectacular Abra del Cóndor, a 4,000-meter (13,000ft) -high mountain pass marking the border between Salta and Jujuy. From Iruya you can visit yet smaller villages, some of which are not even on the maps, as well as the Pucará de Titiconte, a pre-Columbian fort.

TIP

South of Humahuaca, in the tiny hamlet of Huacalera, a large sundial and a monolith mark the exact point of the Tropic of Capricorn (23 degrees and 27 minutes south of the Equator). This is a popular stopping-off point for travelers on Ruta 9 although there is little else to see here (the village church contains some fine paintings, but it is often closed).

An even more adventurous trip would be to Abra Pampa and from there to the Monumento Natural Laguna de los Pozuelos, where you can see huge flocks of the spectacular Andean flamingo, and vicuña herds grazing near the road. Near Abra Pampa there is a huge vicuña farm.

Here in the heart of the Altiplano or puna (with an average altitude of 3,500 meters/11,500ft), are some of the most interesting villages in the Northwest, in a region inhabited for thousands of years before the arrival of the Spanish, and occupied by the Incas during the expansion of their empire southward from Bolivia. Many of the isolated villages have surprisingly large and richly decorated colonial churches, including those at Casabindo, Cochinoca, Pozuelos, Tafna, and Rinconada, which can all be reached by small access roads that wind through the peaceful countryside. RN9 continues all the way to La Quiaca, at the Argentine border, opposite the Bolivian town of Villazón. This has also suffered with the closure of the railway, but still has a colorful market.

The end of the road

Finally, as if saved for a happy ending to this excursion, there remains one of the most sparkling jewels of Argentina: the ancient Iglesia de Nuestra Señora del Rosario y San Francisco, in Yavi.

The tiny village of Yavi 6 [map], on the windy and barren high plateau near the Bolivian border, lies protected in a small depression, about 15km (9 miles) by paved road to the east of La Quiaca. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, Yavi was the seat of the Marqués de Campero, one of the wealthiest Spanish feudal possessions in this part of the continent. Though the chapel here was originally built in 1690, one of the later marquesses ordered the altar and pulpit to be gilded. The thin alabaster plaques covering the windows create a soft lighting that makes the gilding glow (Tue–Sun 9am–noon and 3.30–6pm).

Salt extraction on Salinas Grandes.

Yadid Levy

Salt flats

A good day trip (or overnighter) from Salta is to Salinas Grandes 7 [map], a 12,000-hectare (30,000-acre) salt flat bestriding the border of Salta and Jujuy. Once a highly salinated lake, the water evaporated over millions of years to leave the waxen, cracked moonscape we see today, lifeless save for the activity of workers harvesting salt. It is obligatory – and remarkably easy – to take a “trick” photograph here: the flat, featureless plain erases perspective and causes background and foreground to overlap.

The salt flats are a favorite place to take photos due to the featureless landscape erasing any sense of perspective.

Yadid Levy

To reach the salt flats from Salta City, take RN51 to Santa Rosa de Tastil, a pre-Inca city discovered in 1903 and dating back to the 14th century. There is a small museum at the site, whose caretaker also offers guided tours around the ruins (Tue–Sat 9am–5.30pm). Continue to San Antonio de los Cobres and then take the unpaved Ex-RN40 to Salinas Grandes. After you’ve seen the salt, return to the city or continue to Purmamarca on RP52.

Exploring the Calchaquí Valleys

Passing as it does through the captivating landscapes of the Calchaquí Valleys, with their outlandish rock formations, high-altitude vineyards and charming towns, the circular route that begins in Salta and passes through Cafayate and Cachi before returning you to the capital is one of Argentina’s great road trips. (You can, of course, do the circuit in the other direction, if you prefer to move counterclockwise.)

Doing the circuit clockwise means that the first leg – 185km (115 miles) southwards to Cafayate on paved RN68 – is straightforward. The road cuts through the Quebrada de las Conchas, more commonly referred to as the Quebrada de Cafayate. Towering over the gorge are some of the region’s best-known rock formations, whose wind-sculpted contours have inspired various nicknames – el Sapo (the Toad), el Fraile (the Friar) and el Obelisco (the Obelisk), for example.

Etchart winery in Cafayate produces Torrontés.

Yadid Levy

Terrific Torrontés

Mention Argentine wine to someone and if they think of anything at all, they will think of Malbec. But this popular red varietal is not the only grape that flourishes in the world’s southernmost vineyards. The lesser-known but increasingly popular Torrontés, for example, is Argentina’s most widely planted white variety. It produces potent (14 percent alcohol on average) but very drinkable wines, with hints of grapefruit and melon. The grape is particularly well suited to the high altitude vineyards of Salta, with their sandy soils, hot days, and chilly nights. Etchart, El Esteco, and Colomé are just three of the wineries in the region producing excellent Torrontés, and you’ll find their labels in most supermarkets.

Cafayate

Cafayate 8 [map] should be earmarked in advance as a place to spend at least one night. There is more to Cafayate than the cathedral, with its rare five naves; its small museums of archeology and wine cultivation; its several bodegas (wine cellars), tapestry artisans, and silversmiths. It is the freshness of the altitude of 1,600 meters (5,300ft) and the shade of its patios, overgrown with vines, that really enchant the visitor. The surroundings of this tiny colonial town are dotted with vineyards and countless archeological remains.

TIP

Among the bodegas worth visiting around Cafayate are Etchart and El Esteco, where guided tours and wine tastings are available.

While not yet on a par with Mendoza, wine tourism in and around Cafayate is growing steadily. Wineries worth visiting include Bodega Jose L. Mounier, also known as Finca Las Nubes; San Pedro de Yacochuya; and Bodega El Esteco, the largest winery in the area. Tour schedules change regularly, so check websites before arranging a visit.

Ruins of Quilmes in Salta province.

Yadid Levy

Quilmes

This vast stronghold of the Calchaquís, located in the Calchaquí Valley, near Santa María, once had as many as 200,000 inhabitants, and was the last indigenous site in Argentina to surrender to the Spanish, in 1667.

The Calchaquís were farmers cultivating a large area of land around the urban settlement, and they developed an impressively integrated social and economic structure. This undoubtedly helped their long resistance of the Spanish – both the invasion and conversion to Christianity.

Quilmes is a paradigm of fine pre-Hispanic urban architecture. Its walls of neatly set flat stones are still perfectly preserved, though the roofs of giant cacti girders vanished long ago. Local guides take the visitor to some of the most interesting parts of this vast complex – its fortifications (requiring quite a steep climb), its residential area, its huge dam, and its reservoir.

At the foot of the ruins is a small museum and a craft shop with very beautiful ceramics and tapestries for sale. The ruins are open daily 9am–5pm, and within the complex there is a hotel and simple restaurant that is interesting for having maintained the architectural style and low profile of the ruins very successfully (although controversial for being built on part of the ruins themselves).

A popular side trip from Cafayate is to the archeological ruins of Quilmes, 55km (34 miles) to the south .

Tricycle ride in Cafayate.

Yadid Levy

North to Cachi on Ruta 40

The next leg of the circuit, from Cafayate to Cachi, is on an unpaved stretch of Route 40. It’s a tough but rewarding drive that crosses the impressive Quebrada de la Flecha. Here, a forest of eroded sandstone spikes provides a spectacle as the play of sun and shadow makes the figures appear to change their shapes. Angastaco 9 [map], the first hamlet worth stopping in, was once an aboriginal settlement, with its primitive adobe huts standing on the slopes of immobile sand dunes. In the center there is a comfortable hostería. Angastaco lies amid extensive vineyards, though between this point and the north, more red chili peppers than grapes are grown.

Cafayate vineyards.

Yadid Levy

Molinos ) [map], with its massive adobe church and colonial streets, is another quiet place worth a stop. Molino means mill, and one can still see the town’s old water-driven mill grinding corn and other grains by the bank of the Calchaquí River. Across the river is an artists’ cooperative, housed in a beautifully renovated colonial home, complete with a large patio, arches, and an inner courtyard. The local craftspeople sell only handmade goods, including sweaters, rugs, and tapestries. At Seclantás and the nearby hamlet of Solco, artisans continue to produce the traditional handwoven ponchos de Güemes, red and black blankets made of fine wool that are carried over the shoulders of the proud gauchos of Salta.

If you have time, take a side trip from Molinos to Bodega Colomé, where grapes from some of the world’s highest vineyards are elaborated into lip-smackingly full-bodied wines. It’s also the home of Argentina’s most incongruous contemporary art museum: the Museo James Turrell. Turrell is a well-known and highly respected conceptual artist from California, and this purpose-built space houses many of his beguiling “light and space” installations, drawn from the personal collection of Donald Hess, Colomé’s owner.

San José de Cachi church.

Yadid Levy

Cachi and around

The loveliest place on the circuit is Cachi ! [map], 175km (108 miles) north of Cafayate. The town’s main square is as pretty and well maintained as any in Argentina. Flanking it is a church from 1796, San José de Cachi, many of whose furnishings and structural features (altar, confessionals, pews, even the roof and the floor) are made of cactus wood, one of the few building materials available in the area. Across the square lies the excellent archeological museum Pío Pablo Díaz (Mon–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat– Sun 10am–1pm; charge), whose information panels and 5,000 exhibits tell the story of the region’s inhabitants from 10,000 years ago to the Spanish conquest.

For closer views of Mount Cachi and a glimpse of the beautiful farms and country houses, be sure to visit Cachi Adentro, a tiny village 6km (4 miles) from Cachi proper. RN40 at this point becomes almost impassable, although you can visit the sleepy village of La Poma, 50km (30 miles) to the north and partly destroyed by an earthquake in 1930. But the main tourist route runs to the east over a high plateau called Tin-Tin, the native terrain of the sleek, giant cardón, or candelabra cactus. The Parque Nacional Los Cardones was designated a national park in 1997 to protect the endangered and distinctive cactus.

Down the spectacular Cuesta del Obispo Pass, through the multicolored Quebrada de Escoipe and over the lush plains of the Lerma Valley the road stretches to Salta. From Cafayate to Salta, via Cachi, without stopovers, it is a demanding eight-hour drive.

Towards Tucumán

Only a tiny proportion of visitors to the Northwest venture south of Cafayate, into the provinces of Tucumán, Catamarca, and Santiago del Estero. In the remoter parts of these regions, the tourism infrastructure dwindles to vanishing point. (For the adventurous this, of course, is the attraction.)

Around 68km (42 miles) south of Cafayate, via RN40 and then RP307 into the province of Tucumán, is the town of Amaicha del Valle @ [map], a favorite vacation spot for residents of Tucumán city, many of whom have weekend homes here. Local tradition has it that the sun shines 360 days of the year here. Some hotel owners are so fond of this bit of lore that they reimburse their guests if an entire visit should pass without any sun at all. The local handwoven tapestries and the workshops certainly merit the visit. It has a permanent population almost exclusively of indigenous origin, which is the only indigenous community in Argentina to have been given the titles to its traditional lands (by the Perón government in the early 1970s).

Although Amaicha tends to be hot during the day throughout the year, the high altitude and sparklingly clear air make it cold at night even in summer: a sharp change in temperature which is refreshing and requires warm clothes, even at the height of summer.

Traditional offerings to the Pachamama.

Getty

The Mother of all Deities

If you are traveling Argentina’s north country, particularly through the province of Jujuy, do not be surprised to see someone digging a hole in the ground and then filling it with cigarettes, coca leaves, cheap wine, and perhaps a ladle or two of llama stew.

This ritual is known as the challa and you are most likely to see people performing it on August 1 and at various intervals throughout the rest of that month. The intended recipient of these offerings is Pachamama or the Earth Mother, the most important deity in the Quechua and Aymara pantheons.

If this does not sound very Roman Catholic, that is because it isn’t. But like the Incas in whose conquering footsteps they followed, the Spanish were pragmatic as well as ruthless. They intuited that the pagan Amerindians would be more likely to embrace Christianity if their most treasured cultural rituals were left intact. Furthermore, with a little prodding from Spanish missionaries, these rituals could be given a new spin consistent with the doctrine of the gospels.

And so it has turned out, with the result that it is no longer clear where the Virgin Mary begins and Pachamama ends. So if you are wondering whether that person burying wine in the ground is a Pachamamista or a Christian, the likely answer is that they are both.

Every year, coinciding with Carnival, the traditional indigenous Fiesta Nacional de la Pachamama (Mother Earth Festival; see box) is celebrated here, to give thanks for the fertility of the earth and livestock. An elderly local woman is chosen to play the part of the Pachamama, dressing up and offering wine to all participants. A recent rise in tourist interest has made the week-long festival somewhat more commercial, but it sticks to tradition and offers ritual ceremony, music, and dance.

Stone circles

Tafí del Valle £ [map], 56km (35 miles) south of Amaicha del Valle, is situated in the heart of the Aconquija range. The area was sacred to the Diaguitas, who, with different tribal names, inhabited the area. The valley is littered with clusters of aboriginal dwellings and dozens of sacred stone circles.

Horses graze in Tafí del Valle.

Yadid Levy

By far the most outstanding attractions at Tafí are the menhirs, or standing stones. These stones, which sometimes stand more than two meters (6ft) high, were assembled at the Parque de los Menhires, close to the entrance of the valley, by the government of General Antonio Bussi, moving them from their original positions when the La Angostura dam was built. The dam and lake are in an idyllic mountain setting. The town of Tafí itself, with a dry and cool mountain climate, is a favorite retreat for local residents, with beautiful views, coffee houses, and artisan crafts, foods (especially cheeses), and sweets.

Tucumán province

The province of Tucumán – the smallest of the 24 Argentine federal provinces – is famous for its citrus fruit and sugar cane production and is popularly known as the Garden of the Republic. This climatic and visual contrast is most vividly marked along the Aconquija range, which has several peaks of more than 5,500 meters (18,000ft). The intense greenery is juxtaposed with snowcapped peaks. The best time of year to visit is in winter (June–Aug), when the weather is usually warm and dry; in the summer months it is often stiflingly hot and heavy rains are common.

Tucumán city

In addition to its very visible colonial past, Tucumán $ [map], previously known as San Miguel de Tucumán, is the only city in the Northwest with a very large immigrant population, especially of Italian, Arab, and Jewish settlers. As a result, it has traditionally been a thriving commercial center with a pace of life more similar to Buenos Aires than to the slower-paced cities of the north. It was also the first industrial center in the Northwest, which, together with its historical past as the main commercial center between Buenos Aires and Bolivia and Peru, make it a fairly cosmopolitan and very lively place.

San Francisco church in Tucumán city.

iStockphoto

The spacious Parque 9 de Julio, the Baroque Casa de Gobierno, and several patrician edifices, together with a number of venerable churches, are reminders of the town’s colonial past. This may best be appreciated by visiting the Casa Histórica de la Independencia (daily 10am–6pm; charge). In a large room of this stately house, part of which has been rebuilt, the Argentine national independence ceremony took place on July 9, 1816.

TIP

Tucumán’s Casa de la Independencia puts on a nightly son et lumière show, re-enacting the city’s key role in Argentina’s independence (Wed–Mon 8.30pm). The show is in Spanish only.

The principal colonial churches in Tucumán are the cathedral and San Francisco Church (daily), both located on the plaza; Santo Domingo Church (Mon–Fri), on 9 de Julio and also operating as a school; and La Merced (daily), on the corner of 24 de Septiembre and Las Heras, which houses a famous image of Tucumán’s patroness, the Virgin of Mercy.

Typical Tucumán city architecture.

Bigstock.com

Salt flats and volcanoes

The southernmost region covered in this section, Catamarca offers stark geographical highlights. This province has the greatest altitude differences imaginable; toward Córdoba and Santiago del Estero in the east, the vast Salinas Grandes salt flats are barely 400 meters (1,300ft) above sea level, while in the west, near the Chilean border, the Ojos del Salado volcano reaches the vertiginous height of 6,864 meters (22,520ft), making it the highest active volcano in the world.

In the capital, San Fernando del Valle de Catamarca % [map], points of interest include the Catedral Basílica, containing the famous wooden Virgin of the Valley, discovered being worshiped by Amerindians in the 17th century; the convent of San Francisco; archeological and historical museums; and a permanent arts and crafts fair, best known for rugs and tapestries, located a few blocks from the center.

Around San Fernando del Valle de Catamarca

The country around the capital is lovely, and several side trips are worth mentioning. Time permitting, a trip to the old indigenous settlements scattered on RN40 is highly recommended. The road crosses the province through a series of valleys and river beds, surrounded by dusty mountains. These towns still give a strong impression of how they were hundreds of years ago, and their small museums, traditional chapels, and the spectacular landscape make for a worthwhile trip. The most visited of these towns are Tinogasta, Belén, Londres and Santa María. Look for the thermal spas along the route, one of the most developed being at Fiambalá ^ [map], 48km (30 miles) north of Tinogasta. Fiambalá, which is also famous for its woven ponchos, is an oasis surrounded by vineyards. Its thermal spa is located 15km (9 miles) to the east of the town, in a ravine with waterfalls, and has been used for its curative waters since pre-Columbian times.

TIP

Running northwest of San Fernando, Ruta Nacional 40 and Ruta Provincial 43 leading to Antofagasta de la Sierra cross some of the remotest parts of the Northwest. Facilities are very limited and road conditions highly variable, so it is vital to seek local advice before you set out.

For the adventurous, there is Antofagasta de la Sierra & [map], about 250km (155 miles) north of RN40, located in the puna region of northern Catamarca. Remote Antofagasta is 3,500 meters (11,482ft) above sea level and nearby are lagoons, volcanoes, and salt flats. High-quality textiles can be bought here, especially during March, when a craft and agricultural fair is held in the town.

Santiago del Estero

To the east of Catamarca lie the dusty flats of Santiago del Estero province. Along with Chaco and Formosa, this huge province is one of the least-visited in the country. It has a proud cultural tradition (it is one of the cradles of Argentine folkloric music) but few obvious points of interest and next to no tourism infrastructure. The capital of the province, bearing the same name, was founded by the Spanish in 1553, making it the oldest continuously inhabited city of the region. The city of Santiago del Estero * [map] is also home to the first university established in Argentine territory, and some very attractive colonial buildings remain near the central plaza.

Jungle retreats

Although the Northwest is mainly known for its valleys, plains, and uplands, there are several large areas dominated by dense, subtropical forest. A number of national parks have been created to protect these fragile ecosystems, and while they’re difficult to get to, jungle lovers may consider it worth the effort.

Parque Nacional El Rey is located in the heart of the yungas or subtropical jungle region, 80km (50 miles) east of Salta. It’s a natural hothouse with tropical vegetation as dense and green as one can find almost anywhere in South America. Visitors who come to fish, study the flora and fauna, or just to relax, will find ample accommodations; there is a clean hostería, some bungalows, and a campground. The park is only accessible by car or pre-arranged transportation from Salta, and the best time to visit is between the months of May and October.

Parque Nacional Calilegua occupies 76,000 hectares (188,000 acres) in the east of Jujuy province. Calilegua is primarily tropical yunga forest, like El Rey, although as the altitude climbs the topography changes to mountain jungle, mountain forest, and eventually mountain plains. The park has a campsite, several rivers, and a wide range of wildlife, including wild boar and jaguars, in an exceptionally diverse ecosystem. In 2000, environmental groups lost their fight to stop a gas pipeline being constructed through the park.