Patagonia

Where the Americas end, great adventures begin – this immense region with its limitless horizons tempts the explorer with everything from primeval landscapes to mountain sports

Main Attractions

Extending southwards from the southern banks of the Río Colorado to the icy waters of the South Atlantic, Patagonia is where South America tapers, fragments, and then ends. But like every good magician, the continent has held back some of its most astounding tricks for the finale.

It’s important to realize, however, that the Patagonia of the glossy magazines and coffee table books – the Patagonia of primeval forests, crystalline, trout-torn rivers, glaciers as high as apartment buildings, and jewel-surfaced lakes fed by Andean melt water – is only a fraction of the whole. The rest is desert or steppe: a harsh environment in which only straggly bushes and the hardy breeds of sheep that graze on them can eke out a living. It is on the fringes of this tableland, among the Andean foothills in the west and along the Atlantic coast in the east, that the region’s exotic scenery and wildlife can be found. Imagine a blank canvas in an ornate frame and you will have a good idea of what Patagonia is really like.

Lago Argentino in Parque Nacional Los Glaciares.

Yadid Levy

At the top of the wedge-shaped territory are the provinces of Neuquén and Río Negro, the former famed for its ancient Araucaria araucana (monkey-puzzle) forests and Mapuche reservations, and the latter for the Alpine-style town of Bariloche in Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi. Both provinces border on beautiful Lago Nahuel Huapi, have their own ski resorts, and offer summer hiking, horseback riding, mountain climbing, and water sports.

Farther south, Chubut flaunts the marine fauna of the Valdés Peninsula and an exotic cultural mix comprising the Mapuches and the customs of the Welsh communities of the Atlantic coast and the hinterland. Puerto Madryn’s Golfo Nuevo is Argentina’s scuba-diving capital and is home to the southern right whale during the winter and fall months. Santa Cruz, at the tip of the Patagonian wedge, is the country’s second largest and least-inhabited province. It harbors some of nature’s most imposing glaciers, a large petrified forest that is 150 million years old, and numerous cave paintings more than 10,000 years old.

Patagonia in Print

Nobody has ever expressed more precisely than British naturalist Charles Darwin the emotions that remote Patagonia stirs in a visitor. Darwin, back in England after sailing five years on the Beagle, wrote, “In calling up images of the past, I find that the plains of Patagonia frequently cross before my eyes; yet these plains are pronounced by all wretched and useless… Why then…have these arid wastes taken so firm a hold on my memory?”

Since Darwin’s time, Patagonia has attracted a steady stream of foreign writers. In the 19th century, Argentine-born W.H. Hudson wrote Idle Days in Patagonia, a poetic narrative of his youth spent discovering the flora and fauna of the region.

But perhaps the best-known modern account of the place and its people is Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia (1977), which captures the essence of Patagonia through his meetings with local inhabitants encountered during his travels: “So next day, as we drove through the desert, I sleepily watched the rags of silver cloud spinning across the sky, and the sea of grey-green thornscrub lying off in sweeps and rising in terraces and the white dust streaming off the saltpans, and, on the horizon, land and sky dissolving into an absence of color.”

Patagonia discovered

Ferdinand Magellan, Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, Francis Drake, and Thomas Cavendish are just a few of the many explorers who set foot on this land. Here, European law and customs gave way to the most violent passions; revolts, mutinies, banishments, and executions were common. In 1578, in the port of San Julian (now the town of Puerto San Julián in Santa Cruz province), Sir Francis Drake used the same scaffold Magellan had used to hang his mutineers half a century before.

FACT

The origin of the name Patagonia, according to some historians, comes from the name given to the natives by Ferdinand Magellan because of their big feet (pata is Spanish for an animal’s foot, -gón is a common affix for “big”). Antonio Pigafetta, Magellan’s assistant, commented, on spotting one of the natives, that he was so tall that even the tallest of the crew would only come up to his waist.

The early inhabitants of this land were, from the start, part of the exotic spell that attracted the first settlers, but soon became an obstacle to their purposes. They had been there long before the white man arrived and they stood their ground. The bravest were the Mapuches, a nomadic tribe who lived on both sides of the Andes in the northern part of Patagonia. For 300 years they led a violent lifestyle on the plains by stealing and plundering the larger estancias (ranches) of the rich pampas, herding the cattle over the Andes and selling them to the Spaniards on the Chilean side.

In 1879, the Argentine Army, under General Roca, set out to conquer the land from the Amerindians. The campaign, which lasted until 1883, is known as the Conquest of the Desert. It put an end to years of Amerindian dominion in Patagonia and opened up a whole new territory to colonization. The natives vanished: some died in epic battles, others succumbed to new diseases, and others simply became cow hands on the huge estancias. Fragments of their world can still be found in the land, in the features of some of the people, in customs, and in religious rituals still performed on Amerindian reservations.

Patagonian gaucho.

Yadid Levy

Patagonia settled

When the Amerindian wars ended, colonization began. The large inland plateau, a dry expanse of shrubs and alkaline lagoons, was slowly occupied by people of very diverse origins: Spaniards, Italians, Scots, and English in the far south, Welsh in the Chubut Valley, Italians in the Río Negro Valley, Swiss and Germans in the northern Lake District, and a few North Americans scattered throughout the country.

The Patagonian towns grew fast. Coal mining, oilfields, agriculture, industry, large hydroelectrical projects, and tourism attracted people from all over the country and from Chile, transforming Patagonia into a modern industrial frontier land. Some people came to start a quiet new life in the midst of mountains, forests, and lakes. In the Patagonian interior, descendants of the first sheep-breeding settlers and their ranch hands still ride over the enormous estancias.

FACT

Visitors from the crowded parts of Europe and North America often find it hard to comprehend the sheer emptiness of Patagonia. The population density here averages fewer than three inhabitants per square kilometer (less than one per square mile), compared to more than 2,500 people per square kilometer (more than 1,000 per square mile) in the metropolis of Buenos Aires.

Geography

With defined geographical and political boundaries, Patagonia extends from the Río Colorado in the north, more than 2,000km (1,200 miles) to Cabo de Hornos (Cape Horn) at the southernmost tip of the continent. It covers more than 1 million sq km (400,000 sq miles) and belongs to two neighboring countries, Chile and Argentina. The Argentine part of Patagonia comprises 800,000 sq km (308,000 sq miles), and is usually divided into three definite areas: the coast, the plateau, and the Andes. As these categories are not particularly helpful for tourists, this chapter is organized according to the region’s most popular and worthwhile destinations, which are as follows. First, the northern Lake District, which follows the spine of the Andean cordillera southwards from Villa Pehuenia in Neuquén province to Bariloche in Río Negro. This region is well developed for tourism and includes several of the country’s largest and most impressive national parks. Second, the Atlantic coastline, and in particular the whale-watching destinations of Puerto Madryn and Puerto Pirámides. Finally, the deep south or the southern Lake District, where the towns of El Calafate and El Chaltén attract glacier watchers and hikers respectively. (Although Tierra del Fuego is part of Patagonia, it is dealt with in a separate chapter.)

TIP

There are only two main roads in Patagonia: the legendary RN40, which runs down the Andes, and RN3, which follows the Atlantic coast. Many smaller roads link the coast to the mountains, but few are paved, so you may have to choose between a smooth but longer journey or a quick but bumpy dirt road.

Planning your trip

Unless you are on a two-year sabbatical and have an all-terrain 4x4 vehicle and a love of strong, persistent gales, you are not going to explore all of Patagonia or even come close. The keys to planning an enjoyable trip to the region are to be selective and realistic. You can always return.

The good news is that, thanks to the distance-obliterating magic of air travel, all of the main destinations mentioned above are suitable for a short break. A weekend in the Lake District, for example, gives you enough time to take a boat trip, do a short hike, and eat your way through many of the local specialties. In El Calafate, farther south, this is plenty enough time to explore Parque Nacional Los Glaciares and perhaps even do a side trip to the trekking capital of El Chaltén. At the Atlantic coast you can be on a whale-watching expedition (in season) within a couple of hours of landing at the airport. The tourism infrastructure at these popular destinations is improving all the time, and getting around Patagonia is often less frustrating than crossing Buenos Aires.

If you want to visit more than one of these places, or to penetrate the region’s vast central wilderness, allow yourself at least a week. In the Lake District alone there are many small towns and protected areas worth exploring, most of which are connected by good roads. Cross-country drives, on the other hand, are a serious undertaking. The state of the roads and weather conditions are both difficult to predict, and fuel is scarce.

When to go

Seasons are well-defined in Patagonia. Considering the latitude, the average temperature is mild; winters are never as cold and summers never as warm as in similar latitudes in the northern hemisphere. The average temperature in Ushuaia is 6°C (43°F) and, in Bariloche, 8°C (46°F). Even so, the climate can turn quite rough on the desert plateau. There, the weather is more continental than in the rest of the region. The ever-present companion is the wind, which blows hard all year round, from the mountains to the sea, making life here unbearable for many people.

In spring, the snow on the mountains begins to melt, alpine flowers bloom almost everywhere, and ranchers prepare for the hard work of tending sheep and shearing. Although tourism starts in late springtime, most people visit during the summer (December to March). During this period, all roads are fit for traffic, the airports are open and, normally, the hotels are booked solid.

The fall brings changes on the plateau. The poplars around the lonesome estancias turn to beautiful shades of yellow. The mountains, covered by deciduous beech trees, offer a panorama of reds and yellows, and the air slowly gets colder. At this time of the year, tourism thins out. Parque Nacional Los Glaciares , in the far south, closes down for the winter. While the wide plains sleep, the winter resorts on the mountains thrive. San Martín de los Andes, Bariloche, Esquel, and even Ushuaia attract thousands of skiers, including many from the northern hemisphere who take advantage of the reversal of seasons.

FACT

The19th-century English explorer George Musters wrote At Home with the Patagonians (1871), about his year-long journey through the region with a group of Amerindians. The book earned him a gold watch from the Royal Geographical Society, and is still hailed as the most complete description of the Patagonian interior and its people.

The northern Lake District

Going west from Neuquén to the Andes, you come to the northern limit of the Patagonian Lake District, an enormous area of beautiful lakes and spectacular mountain peaks, which stretches 1,500km (900 miles) from Lago Aluminé in the north to Parque Nacional Los Glaciares in the south. One can divide this region into two sections, the northern and southern Lake Districts. The zone that lies in between is sparsely populated and traveling is a challenge to be taken on only by the most adventurous.

January and July are the most popular months for visitors, reflecting the vacations in Buenos Aires. However, apart from May and June, which tend to be rainy months, the area has its attractions in all seasons. There are many tours available to local landmarks and abundant opportunities for hiking, climbing, fishing, and horseback riding in summer, or skiing and snowboarding in winter.

TIP

A Pase Verde (Green Pass) allows entry to three national parks – Arrayanes, Nahuel Huapi, and Lanín – and is available from national park offices. It is valid for 15 days but the price varies according to the time of year.

The northern Lake District covers the area from Lago Aluminé southward to Lago Amutui Quimei. It encompasses a 500km (300-mile) stretch of lakes, forests, and mountains divided into four national parks. From north to south is the Parque Nacional Lanín and the nearby towns of San Martín de los Andes and Junín de los Andes; Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi and the Alpine-style resort of Bariloche; Parque Nacional Lago Puelo and the village of El Bolsón; and, farthest south, Parque Nacional Los Alerces with the town of Esquel. This region connects to the so-called Lake District in Chile.

Entering the Lake District from the north, the first place of interest you reach is the Parque Nacional Laguna Blanca. The park lies just to the southwest of Zapala, which is about 185km (115 miles) west of Neuquén on RN22. It includes a large lake, and is home to hundreds of interesting bird species: the prime attractions are the black-necked swans, which gather in flocks of up to 2,000 birds. Flamingos are also part of the scenery, and the surrounding hills give shelter to large groups of eagles, peregrine falcons, and other birds of prey. There is a visitor’s center at the park, and a campsite. There are infrequent buses to the park from the nearest town, Zapala, 35km (22 miles) away, which has an information office.

Villa Pehuenia

Lying 120km (75 miles) west of Zapala, the lovely mountain village of Villa Pehuenia 1 [map] was founded as a tourist resort in 1989. It sits on the banks of Lago Aluminé, the largest of several lakes in the area, many of which attract canoeists and kayakers. The village’s tourism infrastructure is not as sophisticated as that of towns farther south, but most visitors consider this an advantage and welcome the relative lack of crowds. A number of easy and well-marked trails cut through the woodlands encircling the lake, and there are campsites for those who like to carry their accommodations on their backs. Cerro Batea Mahuida, a small ski centre located 5km (3.1 miles) from town, is owned and run by a local Mapuche community. It lacks facilities, but beginners will enjoy its accessibility and complete lack of airs and graces.

This area is also home to one of the most peculiar-looking trees in the world, the Araucaria araucana or monkey puzzle. The village’s name is derived from “Pehuén,” the Mapuche word for these strange and ancient conifers.

San Martín de Los Andes.

Yadid Levy

San Martín de los Andes and Parque Nacional Lanín

The delightful town of San Martín de los Andes 2 [map] is located 208km (129 miles) south of Villa Pehuenia (a five-hour drive on RP23). Set on the banks of Lago Lácar, San Martín has the most beautiful natural harbor in the country, with thickly forested, steep hills rising on three sides, offering a number of vantage points from where you can look down on the town and the colorful skiffs that bob on the waves by the port.

The indigenous Mapuche tribe populated this area long before the town was founded in 1898. The small but interesting Museo de los Primeros Pobladores (Museum of the Original Inhabitants; Mon–Fri 3–7pm), at Juan Manuel de Rosas 700, exhibits Mapuche textiles, tools, and ceramics along with photographs tracing the town’s early history.

To explore Lago Lácar, take one of the regular catamaran tours that depart from the town’s passenger pier at Avenida Costanera y Muelle. They stop at several hidden coves and beaches around the lake shore, including Playa Catitre (which has a campsite) and Villa Quila Quina. You can also use San Martín as base for exploring Parque Nacional Lanín, which covers 3,920 sq km (1,508 sq miles) and gets its name from the imposing Lanín volcano, on the border with Chile. The volcano soars to 3,776 meters (12,388ft), far above the height of the surrounding peaks.

The national park is noted for its fine fishing; the fishing season is from mid-November through mid-April. The rivers and streams around the small town of Junín de los Andes 3 [map] , 42km (26 miles) northwest of San Martín, are famed for their abundance and variety of trout. Fly-casters come from around the world to fish for the brook, brown, fontinalis, and steelhead. The best catch on record is a 12kg (27lb) brown trout – the average weight for this fish is 4–5kg (9–11lbs). Although Junín has several good restaurants and hotels, most anglers prefer the fishermen’s lodges in the park itself.

Parque Nacional Lanín is also well known for hunting. Wild boar and red and fallow deer are the main prey in the fall rutting season. The national park takes bids for hunting rights over most of the hunting grounds, and local farm owners make their own agreements with hunters. For information, contact the tourist office in San Martín de los Andes.

Cerro Chapelco, at 2,441 meters (8,000ft) and 20 minutes or so by car from San Martín, is one of the country’s most important winter-sports centers. The ski season here runs from mid-June to mid-October.

San Martín to Bariloche

Three roads link San Martín de los Andes with Bariloche. The middle (shortest, but unpaved) road runs across the Paso del Córdoba through narrow valleys where the scenery is beautiful, especially in the fall, when the slopes turn to rich shades of gold and deep red. This road reaches the paved highway at Confluencia. From here, if you turn back inland, you come to the Estancia La Primavera, with its trout farm. To the dismay of locals who used to fish here, it is now private property, belonging to US media tycoon Ted Turner. Returning to the paved road to Bariloche, you follow Río Limay through the Valle Encantado, a valley of bizarre rock formations, also skirting the Rincón Grande, a ring of steep escarpments formed by river erosion into a striking natural amphitheater.

The third road from San Martín is the famed Ruta de los Siete Lagos (Route of the Seven Lakes). This road, of which about two-thirds is paved, takes you past beautiful lakes and forests and approaches Bariloche from the northern shore of Lago Nahuel Huapi. In summer, all-day tours make the trip from Bariloche to San Martín, combining the Paso del Córdoba and the Ruta de los Siete Lagos. Another good way of traveling the route is by mountain bike; these can be easily hired in San Martín de los Andes.

Native monkey-puzzle tree in Parque Nacional Lanín.

Yadid Levy

Crossing the Andes

While you are in the northern Lake District there are various options for crossing over to Chile. From Bariloche, if you want to reach Puerto Montt on the Pacific coast, try the old route first used by the Jesuits across the lakes. This day-long journey combines short bus rides with leisurely boat crossings of lakes Nahuel Huapi, Frías, Todos los Santos, and Llanquihue, through marvelous settings of forests and snowcapped volcanoes.

While the lake crossing has the advantage of escaping normal traffic, the road through the Puyehue Pass, northwest of Bariloche, gives views of Lago Correntoso and Lago Espejo. Over the border, the Parque Nacional Puyehue offers the opportunity to sample thermal springs and mud baths, or to explore the temperate rainforest.

Farther north, via San Martín de los Andes, is the little-used Hua-Hum Pass. A small car ferry carries you the length of Lago Pirihueico with its steep-forested sides and glimpses of the Choshuenco volcano, and at the far end a road continues into the village of Choshuenco.

More northerly still, beyond Junín de los Andes, is Paso Tromen. This road is much higher and sometimes closed in winter, but affords wonderful views of the Lanín volcano and the native Araucaria (monkey-puzzle) forests.

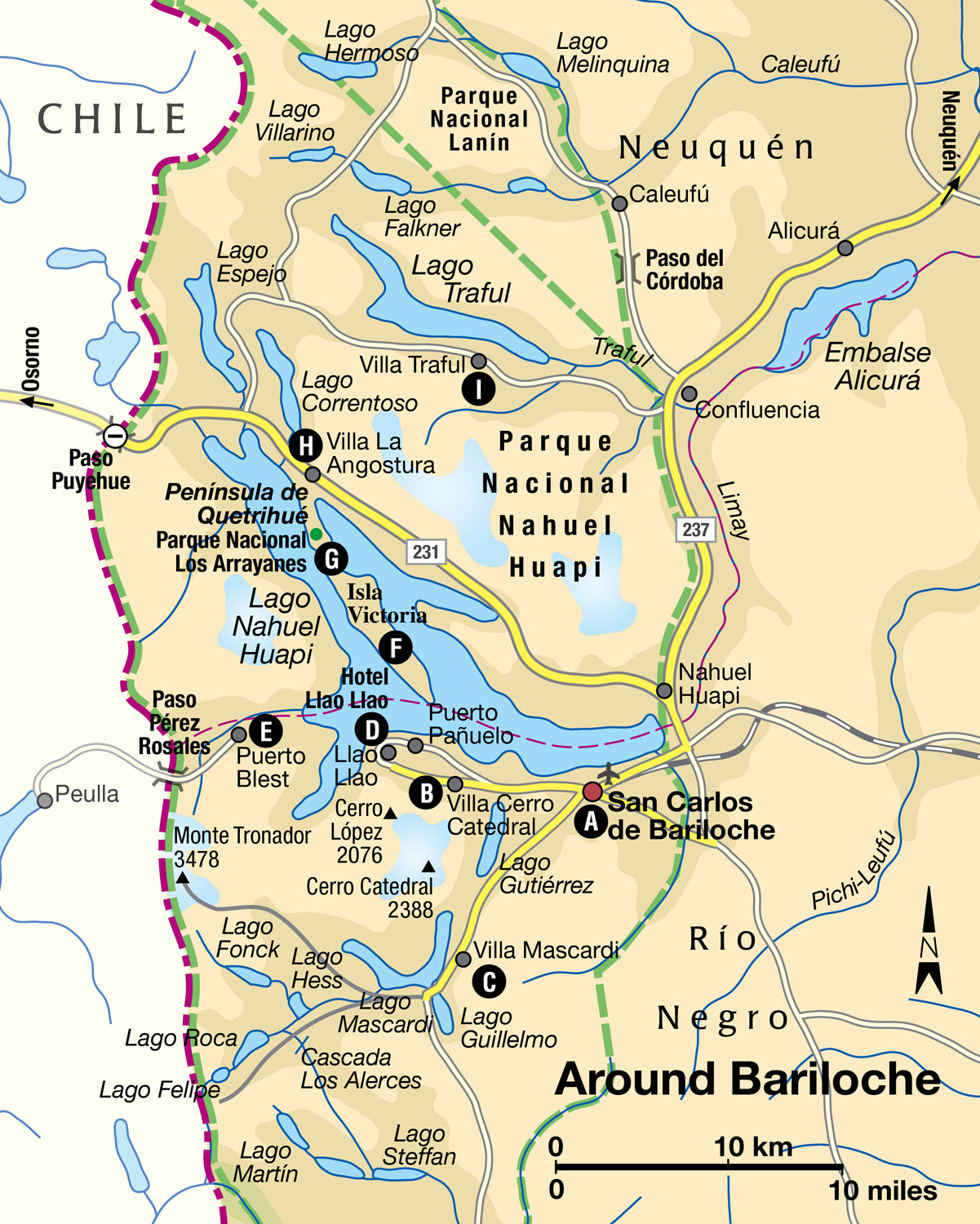

Bariloche

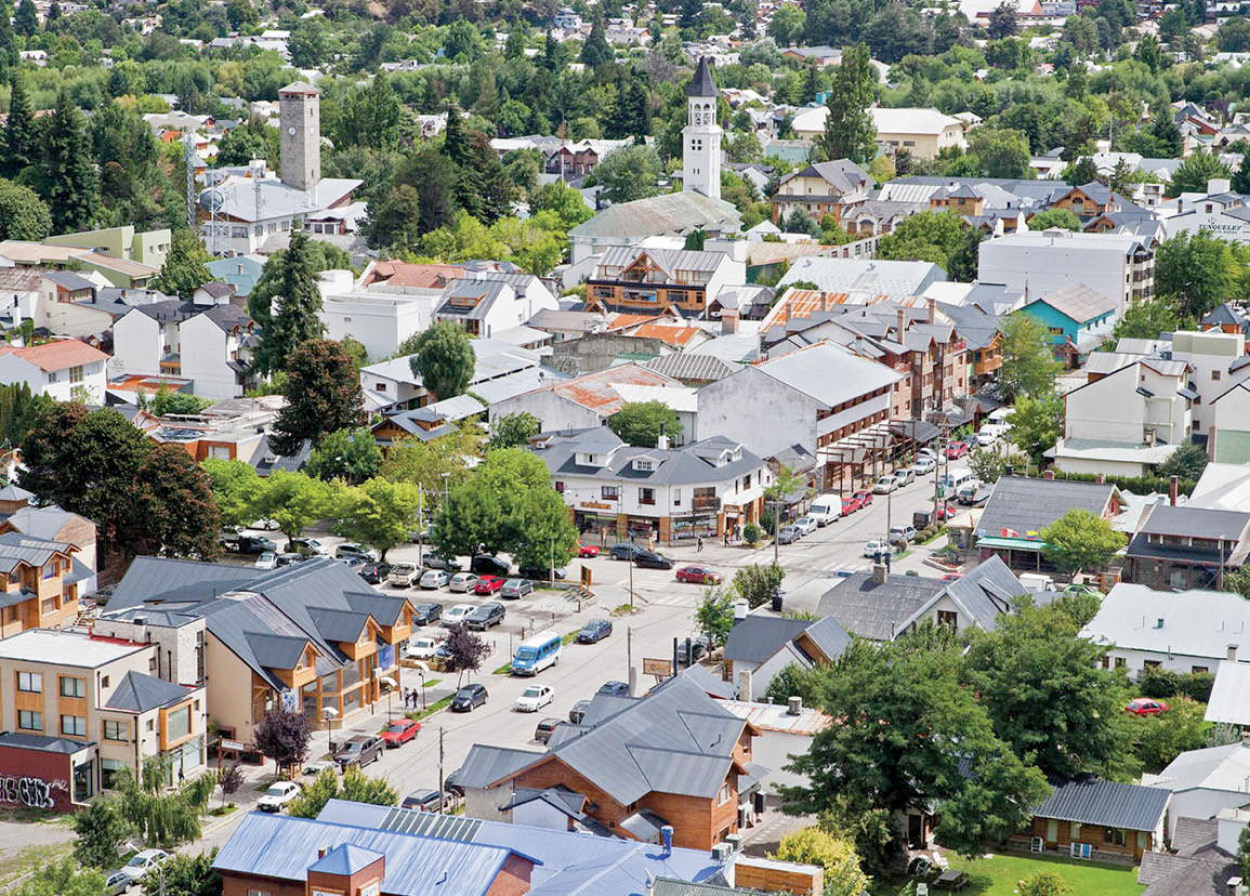

San Carlos de Bariloche A [map] in the middle of Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi, is the real center of the northern Lake District and a year-round destination for hikers, nature lovers, high school students (they come here to celebrate their graduation), and, in winter, skiers. Buses, trains, and planes arrive daily from all over the country and from Chile, across the Paso Puyehue.

Founded in 1902, Bariloche, as it is almost always known, has a very strong Central European influence; most of the first settlers were of Swiss, German, or northern Italian origin. These people gave the city its Alpine atmosphere, with Swiss-style chalets, fondue restaurants, and chocolates. However, something tells you that you are not in Europe; boats are seldom seen on the huge Lago Nahuel Huapi, the roads are swallowed in the wilderness as soon as they leave the city, and at night there are no lights on the opposite shore of the lake.

The town has grown rapidly in recent decades, spreading along the foot of Cerro Otto. This long ridge offers a good introductory walk, or take a cable-car ride to the top, from where there are splendid views of the town, the lake, and the surrounding park, as well as a revolving café. There are also pleasant woodland walks descending the far side of the ridge to Arelauquen and the quiet Lago Gutiérrez.

Bariloche’s town center.

Yadid Levy

The best way to begin your tour of Bariloche is by visiting the Museo de la Patagonia (Tue–Fri 10am–12.30pm and 2–7pm; Sat 10am–5pm; charge) in the Civic Center. This building and the Hotel Llao Llao were designed by architect Alejandro Bustillo in his own interpretation of traditional Alpine style, and they give Bariloche a distinctive architectural personality. The museum has displays on the geological origins of the region and of local wildlife. It also has a stunning collection of indigenous artifacts, which chronicle the demise of local tribes.

Demise of the rail network.

iStockphoto

Railroad to Nowhere

It is a fact that can bring tears to the eyes of trainspotters: Argentina’s once great rail network, which used to crisscross the length and breadth of the country, is no more. It was “rationalized” out of existence during the great privatization spree of the 1990s.

Well, almost out of existence. One epic intercity service remains: the Tren Patagónico which connects Viedma on the Atlantic coast with Bariloche in the Andean foothills. The journey of 850km (528 miles) takes around 18 hours – and apart from the short and scenic approach to (or departure from) Bariloche, that is 18 hours spent crossing the Patagonian desert: a brutal, wind-tormented, almost treeless landscape. The feeling of truly arriving in the middle of nowhere can be both sublime and unnerving, and while this is unquestionably the trip of a lifetime, it is one few people would dare repeat.

Tourists and workers on their weekly commute mix on the train, which offers (for the former at least) pullman carriages and individual compartments with bunk beds. As well as a restaurant car serving an excellent three-course meal, there is a cinema wagon which screens several movies during the trip. The train departs from Viedma every Friday evening and returns eastwards on the Sunday. For more information visit www.trenpatagonico-sa.com.ar.

Around Bariloche

There are some excellent excursions to choose from in the Bariloche area: 17km (11 miles) southwest is the Villa Cerro Catedral B [map] , South America’s largest and most important ski center, also with fine hiking trails on the mountainside and around Lago Gutiérrez. The base of the ski lifts is at 1,050 meters (3,465ft) above sea level, and a cable car and chair-lifts take you up to a height of 2,010 meters (6,633ft). The view from the slopes is absolutely superb. The ski runs range in difficulty from novice to expert, covering more than 25km (15 miles), and there are full facilities. The ski season runs from the end of June to September and peaks in late August with the four-day annual Fiesta de la Nieve, whose highlight is a torch-lit parade down the mountainside. Snowboarding, bungee jumping, and paragliding are also possible.

Another 10km (6 miles) farther south is Villa Mascardi C [map] , a small tourist resort on the shore of Lago Mascardi. Picturesque boat cruises are available from here across the turquoise waters of the lake toward Monte Tronador, the highest peak in the national park, at 3,478 meters (11,411ft). The mountain can also be visited via a long and winding scenic drive. Between lakes Gutiérrez and Mascardi lies the watershed of rivers draining into the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. Past Pampa Linda, where there is one hostel, and approaching the mountain, you pass the Black Glacier, so-called because of all the muddy debris churned up onto the surface of the glacier. Another route from Lago Mascardi goes to lakes Fonck and Hess, both popular fishing spots, with campsites. En route, you pass the lovely Cascada Los Alerces, which cascades for some 20 meters (66ft) over drenched, mossy rocks. A number of these routes operate one-way systems allowing only ascent or descent within certain times, in order to regulate peak season tourist traffic, so you would be advised to check the details at the Bariloche tourist office if traveling independently by road.

Local grocery shop in Bariloche.

Yadid Levy

Llao Llao Peninsula

One of the most popular half-day excursions from Bariloche is the so-called Circuito Chico, or small circuit. This takes you westward along the shore of the lake and up to the Punto Panorámico, with its breathtaking views over the water toward Chile. It is a rare building that could blend into, even enhance, such a magnificent landscape, but the Hotel Llao Llao D [map] at the base of the Península Llao Llao, is equal to the challenge.

Continuing the circuit, farther round the lake is Bahía López, a tranquil inlet where it is often possible to see condors circling the huge bulk of Cerro López overshadowing the bay. There is a well-defined path leading up this mountain as far as the mountain refuge, with a more rugged track thereafter up to the summit ridge. On the road back to Bariloche you will pass the Cerro Campanario chair-lift at km 17. Although much lower than lifts at Cerro Otto or Catedral, the views are unrivaled.

At the far end of Lago Nahuel Huapi, en route to Chile, Puerto Blest E [map] is host to much through traffic. Few stay, however, so outside these brief flurries of traffic it is a place of exceptional peace and beauty. There is a small hotel, a pleasant walking trail to the Cascada Los Cantares, and a warden to give directions for more demanding hikes. You can visit Puerto Blest and Isla Victoria by catamaran excursions across Lago Nahuel Huapi from Puerto Pañuelo.

Bambi’s forest

Isla Victoria F [map] , on Lago Nahuel Huapi, is renowned for its arrayanes, rare trees related to myrtles, found only in this area and in the Parque Nacional Los Alerces . The story goes that a visiting group of Walt Disney’s advisors were so impressed by the white and cinnamon-colored trees here that they used them as the basis for the scenery in the 1942 film Bambi. Most visitors to the island come in groups on the catamaran excursions, but you require only a little ingenuity to discover the beauties of the island away from the crowds.

Extending from the northern shore of the lake is the Península de Quetrihue, containing the Parque Nacional Los Arrayanes G [map] , dedicated to protecting the rare arrayán trees, some of which are 300 years old and 28 meters (92ft) high. Boat excursions to Isla Victoria often stop at Quetrihue, allowing time to walk in the park. You can also reach the Península de Quetrihue from Villa La Angostura H [map] , an increasingly busy chic resort at the far end of the lake. There is a good selection of hotels, campsites, and other amenities in the vicinity, which has been developed to cater to the tourist overflow of the nearby skiing center of Cerro Bayo.

Another popular excursion heads east from Bariloche, then north through the Valle Encantado, until turning off at Confluencia for Villa Traful I [map] . The small town is famous for the excellent salmon fishing in Lago Traful, as well as for some inspiring hiking and horseback riding in the surrounding countryside. The road continues through the town, climbing to a commanding viewpoint high above Lago Traful, and takes a scenic route back through Villa La Angostura. This circuit, predictably described as the Circuito Grande (long circuit), covers some 240km (149 miles) and is offered as a full-day excursion from Bariloche. Most travel agencies in Bariloche offer a variety of bus and boat excursions visiting the above-mentioned sites, but if you fancy something a little more energetic to tap this area’s vast potential for outdoor pursuits, visit the Club Andino, the city’s specialist mountaineering organization.

Handicrafts market at El Bolsón.

Eduardo Gil

El Bolsón

El Bolsón 4 [map] is a small town 130km (80 miles) south of Bariloche, situated in a narrow valley with its own microclimate. Beer hops and all sorts of berries are grown on small farms around the town and made into artisanal beers and preserves respectively. Hippies favored El Bolsón in the 1960s, and today many lead peaceful lives on farms perched in the mountains. Some 20km (12.5 miles) south of El Bolsón, and bordering Chile, is the serene Parque Nacional Lago Puelo (237 sq km/92 sq miles), established in 1937 as an annex to nearby Parque Nacional Los Alerces. Another angler’s paradise, the park has mountains covered with ancient forests of deciduous beech trees and cypresses and more than 100 species of bird. Basic camping facilities are available by the lakeshore, with some marked trails.

QUOTE

“It is not the imagination, it is that nature in these desolate scenes, for a reason to be guessed at by and by, moves us more deeply than in others.”

W.H. Hudson (Anglo-Argentine naturalist, 1841–1922)

Cholila Valley

Farther south, on the road to Esquel, you come across the beautiful Cholila Valley, a little-known area where in early summer the fields are carpeted in blue by wild lupins. This was the place chosen by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the US outlaws made famous by George Hill’s 1969 movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. Butch and Sundance sheltered temporarily in Cholila (you can see the log cabin they built but it is in bad shape and cannot be entered) while they were on the run from Pinkerton’s agents. A letter sent by them to Matilda Davis in Utah, dated August 10, 1902, was posted at Cholila. After their famous hold-up of the Río Gallegos Bank in 1905, they were again on the run, until they were finally killed in Bolivia. Other members of the gang who stayed on in this region were ambushed and killed, years later, by the Argentine constabulary.

From Cholila, the road going south splits in two. RN40 turns slightly to the east, through the large Estancia Leleque, alongside the narrow-gauge railroad, until it reaches Esquel. The other route to Esquel takes you right into Parque Nacional Los Alerces. This park covers 2,630 sq km (1,012 sq miles) and is less spoiled by towns and people than other parks are in this region. Summer visitors to the park stay at campsites and fishermen’s lodges around Lago Futalaufquen. One tour you should not miss is the all-day boat excursion, which leaves in the summer from Puerto Chucao to Lago Menéndez, the largest lake in the national park. There are outstanding views of Cerro Torrecillas (2,200 meters/7,260ft) and its glaciers, and be sure to see the huge Fitzroya trees (related to the American redwood), some of which are over 2,000 years old.

The Old Patagonian Express

As you get closer to Trevelín and Esquel you begin to leave behind the northern Lake District. This area is strongly influenced by Welsh culture, as a sizeable community of Welsh people settled here in 1888 after a long trek from the Atlantic coast along the Chubut Valley .

Esquel’s railway station is the most southerly point of the Argentine rail network.

iStockphoto

Traveling 167km (104 miles) south of El Bolsón on RN40 and RN258 brings you to Esquel 5 [map] , an offshoot of the Welsh Chubut colony. The town, with 32,000 inhabitants, lies to the east of the Andes, on the border of the Patagonian desert – a remote location that gives Esquel the feel of a town in the old American West. You are as likely to see people riding on horseback here as in cars. Sometimes the rider will be a gaucho dandy, all dressed up with broad-brimmed hat, kerchief, and bombachas (baggy pleated pants). Several times a year, principally in January, a rural fair is held in Esquel. People come from miles around to trade livestock and agricultural supplies. In town, several stores (talabarterías) are well stocked with riding tackle and ranch equipment. Ornate stirrups and hand-tooled saddles sit next to braided, rawhide ropes, and cast-iron cookware. This was once goose-hunting country, but the rare local species have since become protected.

Esquel’s railway station is the most southerly point of the Argentine rail network. The narrow-gauge railway (0.75 meters/2.5ft), used to provide a regular service between Esquel and Ingeniero Jacobacci to the north. The train – La Trochita – was made famous abroad by US author Paul Theroux, in his book The Old Patagonian Express (1979). These days it runs only a partial and intermittent schedule largely for the benefit of tourists. Nevertheless, if you happen to arrive at the right time, there is no better way to get acquainted with Patagonia and its people than by a trip on this quaint little train, which is pulled by an old-fashioned steam locomotive. For serious railway buffs, there are workshops open to visitors in El Maitén, providing a further glimpse of the romantic past.

In winter, Esquel turns into a ski resort, with La Hoya Ski Center only 15km (10 miles) away. Compared with Bariloche and Villa Cerro Catedral, this ski area is considerably smaller and cozier but a range of rental facilities is available.

Trevelín 6 [map] , 23km (14 miles) southwest of Esquel, is a small village, also of Welsh origin. Its name in Welsh means “town of the mill.” The old mill has been converted into a museum, the Museo Molino Viejo (daily 11am–9pm), which houses all sorts of implements that belonged to the first Welsh settlers, together with old photographs and a Welsh Bible. As in all the Welsh communities of Patagonia, you can enjoy a typical tea with Welsh cookies and cakes in several cafes in Esquel.

TIP

The tourist office in Puerto Madryn sells a “Pase Azul,” which includes entrance to Península Valdés, the EcoCentro, and other sights, for a reduced fee.

The Atlantic coast: Puerto Madryn

Puerto Madryn 7 [map] is the gateway for visitors to Península Valdés and the Punta Tombo penguin colony. It is a spruce seaside town with extensive sands and flamingos in the bay. The Museo Oceanográfico y de Ciencias Naturales (Mon–Fri 9am–1pm and 3–7pm; charge), on the corner of Domecq and García Menéndez, is worth a visit for its collections of coastal and marine flora and fauna.

Nature lovers will want to visit the EcoCentro, Julio Verne 3784 (Mon–Fri 9am–noon and 3–7pm), where local marine life is explained in various interactive displays and exhibits.

Punta Tombo, 165km (102 miles) south of Madryn (108km/67 miles of which is dirt road), has the largest colony of Magellanic penguins in the world. The penguins arrive in September and stay until March. In this colony you can literally walk among thousands of these comical birds as they come and go along well-defined “penguin highways” that link their nests with the sea across the tourist path, and see them fish near the coast for their meals.

FACT

Years ago, huge quantities of salt were extracted from salt pits on the Península Valdés, and shipped out from Puerto Madryn. The salt was also used to preserve the blubber of the thousands of sea lions killed here during the first half of the 20th century. You will pass the salt flats at Salina Grande and Salina Chica if you take the RP2 from Puerto Pirámides to Punta Delgada.

Puerto Pirámides on Península Valdés.

iStockphoto

Península Valdés 8 [map] is one of the most important wildlife reserves in Argentina and was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1999. It is the breeding ground for southern right whales, elephant seals, and sea lions, and the nesting site for thousands of shore birds, including pelicans, cormorants, and oystercatchers. Guanaco, rhea, and mara can all be spotted with sharp eyes. There is an interpretive center and museum at the entrance to the peninsula itself, which is a large wasteland, with the lowest point on the South American continent, 40 meters (132ft) below sea level. Some 40,000 elephant seals are found along a 200km (125-mile) stretch of coastline, the outer edge of the Valdés Peninsula – the only such colony accessible by land outside Antarctica. Most of the beach is protected but tourists have a chance to observe the wildlife from specially constructed viewing hides at Punta Norte and Caleta Valdés, where two reserves have been established. About 10,000 elephant-seal pups are born each year from late August to early November.

Whale watching

Puerto Pirámides, 95km (59 miles) from Puerto Madryn, was once a major center for whaling and trading in seal skins. In the 19th century there were more than 700 whalers operating in these waters. An international protection treaty was signed in 1935, and since then the whale population has recovered slowly, now standing at about 2,500. The whales come to breed near these shores around July and stay until mid-December. Whale watching is concentrated on mother and calf pairs and is organized by a few authorized, experienced boat owners from Puerto Pirámides . On shore, you can observe the sea lions and cormorant colonies from a viewing platform at the foot of the pyramid-shaped cliff that gives this location its name.

There are a several good hotels and restaurants and a shore-side campsite where you can wake to the sound of whales blowing in the bay. It is an ideal center for exploring the peninsula’s other wildlife sites, too, although if you hire a vehicle, beware of the tricky driving conditions. On the small side road out of the peninsula stands a monument dedicated to the first Spanish settlement here, which lasted only from 1774 to 1810, when the settlers were forced to flee from the native warriors. Here too, is a sea-bird reserve, the Isla de los Pájaros.

Land of Their Fathers

At a time when Argentina was actively seeking pioneers to settle the empty lands of Patagonia, a group of Welsh non-conformists were looking for a new home away from the oppression of the English

Patagonia is partly pampas, largely desert, and unrelentingly windblown, with only small areas of fertile soil and little discovered mineral wealth. Why would anyone leave the lush valleys and green hills of Wales to settle in such a place? The Welsh came, between 1865 and 1914, partly to escape conditions in Wales which they deemed culturally oppressive, partly because of the promise – later discovered to be exaggerated – of exciting economic opportunities, and largely to be able to pursue their religious traditions in their own language.

The disruptions of the 19th-century Industrial Revolution uprooted many Welsh agricultural workers: the cost of delivering produce to market became exorbitant because of turnpike fees, grazing land was enclosed, and landless laborers were exploited. Increasing domination of public life by arrogant English officials further upset the Welsh. Thus alienated in his own land, the Welshman left.

Equally powerful was the effect on the Welsh people of the religious revivals of the period, which precipitated a pious religionism that continued beyond World War I. For many, the worldliness of modern life made impossible the quiet spirituality of earlier times, and they saw their escape in distant, unpopulated areas of the world then opening up. Some had already tried Canada and the United States and were frustrated by the tides of other European nationalities which threatened the purity of their communities. They responded when Argentina offered cheap land to immigrants who would settle and develop its vast spaces before an aggressive Chile pre-empted them. From the United States and from Wales they came in small ships on hazardous voyages to Puerto Madryn, and settled in the Chubut Valley.

Although the hardships of those gritty pioneers are more than a century behind their descendants, the pioneer tradition is proudly remembered. Some remain in agriculture, many are in trade and commerce. Only a dwindling number of the older generation still speaks Welsh, but descendants will proudly show you their chapels and cemeteries (very similar to those in Wales), take you for Welsh tea in one of the area’s many teahouses, and reminisce about their forebears and the difficulties they overcame. They speak of the devastating floods of the Chubut that almost demolished the community at the turn of the 20th century, the scouts who went on indigenous trails to the Andean foothills to settle in the Cwm Hyfrwd (the Beautiful Valley), the loneliness of the prairies in the long cold winters, the incessant winds, and the lack of capital that made all undertakings a matter of backbreaking labor.

Unfortunately, the old ways are being discarded in our modern technological era. The Welsh language will not long be spoken in Patagonia. But traditions are still upheld, and descendants of the Patagonian Welsh still hold eisteddfods to compete in song and verse. They revere the tradition of the chapel even when they do not attend, and they take enormous pride in their links with Wales.

Serving a Welsh tea of bread, jams, and scones in a teahouse in Gaiman.

© Corbis. All Rights Reserved.

The Chubut Valley and the Welsh towns

The lower Chubut Valley was the site of the first settlement established by the Welsh. The towns of Dolavon, Gaiman, Trelew, and Rawson developed here, and today they are surrounded by intensively cultivated lands.

Gaiman 9 [map] is particularly attractive and makes for an excellent day trip from Puerto Madryn (80km/50 miles away via RN3). It has an interesting museum similar to the one in Trevelín, the Museo Histórico Regional (Tue–Sun 3–7pm), housed in the old train station, with a gift shop. The town is famous for its Welsh teas, which are offered by four leading casas de té (teahouses) in somber rooms crowded with evocative memorabilia of the first settlers. An eisteddfod – Welsh arts festival – which features singing and reciting, is held here every August. The river meets the sea close to Rawson ) [map] , the provincial capital city. It is worth driving by the fishermen’s port here to watch the men the men unloading their day’s catch, a host of lazy sea lions bobbing around their skiffs to grab whatever falls overboard.

Trelew is the most important city in the lower valley, and its airport is the gateway for visitors to the wildlife-rich Península Valdés area. After a program to promote industry was introduced in the 1980s, the population swelled here to 100,000. Its Welsh ambiance has faded and, apart from a leafy central square, it is not a particularly attractive city. One point of interest is a paleontological museum marking the important dinosaur remains that have been found in Patagonia. The Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio (daily 9am–7pm), on Avenida Fontana 140, contains fossil remains of dinosaurs such as carnotosaurus, the only known meat-eating dinosaur with horns, and the 65-million-year-old eggs of titanosaurus.

When the Wind Blows

The wind. It is the first thing people notice when they arrive in Patagonia, and the first thing they mention when recounting their trip. It blows across the steppe from the west in a violent, constant stream of air. In a second it can lift a cyclist bodily from their saddle or blow a jeep into a ditch and, over time, it bends trees into submission and clogs machinery with sand and salt.

However, all this power has potential for good as well as mischief. In October 2011, President Cristina Kirchner opened the Rawson Aeolic Park in Chubut. It is Argentina’s largest wind farm and could eventually power 100,000 homes. As the world’s supply of fossil fuels dwindles, Patagonia may find itself on the new energy frontier.

Oil country

Some 440km (270 miles) down the coast south of Trelew is Patagonia’s major city, Comodoro Rivadavia ! [map] , with a population exceeding 160,000. Its airport has daily flights connecting the Patagonian cities and Buenos Aires.

Colonia Sarmiento @ [map] , 190km (118 miles) west of Comodoro Rivadavia, lies in a fertile valley flanked by two huge lakes, lagos Musters and Colhué Huapi, which attract black-necked swans. Heading south from the valley for 30km (19 miles), you reach the Monumento Natural Bosques Petrificados, which has remains that are more than a million years old. This forest tells us much about the geological past of this land, which a long time ago was covered in trees.

Santa Cruz

The province of Santa Cruz is the second largest in Argentina but with the smallest population per square kilometer. Most of Santa Cruz is dry grassland or semidesert, with high mesetas (plateaux) interspersed with protected valleys and covered with large sheep estancias.

Sheep graze by the Córdoba Pass.

Yadid Levy/Apa Publications

Shear Profit

The first governor of Santa Cruz, Carlos Moyano, could find no one to settle in the desolate south of Patagonia. In desperation, he invited young couples from the Malvinas/Falklands to try their hand “on the coast,” and the first sheep farmers were English and Scottish shepherds. They were soon followed by people from many other nations, mainly in central Europe, who remained behind after the 1890s gold rush. The sheep rearing proved hugely successful, and, by the 1920s, Argentinian wool commanded record prices on the world market.

The sheep in southern Patagonia are mainly Scottish corriedale, although some merinos have been brought from Australia, and two hardy new breeds have been developed for the region. Farm work intensifies from October to April, with lamb marking, shearing, dipping, and moving the animals to the summer camps. In the fall they are moved back to the winter camps and the wool around the eyes is shorn.

Shearing is usually done by a comparsa, a group of professionals who travel from farm to farm, moving south with the season. However, each farm has its own shepherds and peones (unskilled workmen) who stay year round, tending fences and animals.

RN3, nearly all of which is paved, is the province’s main coastal road. It follows the shoreline of Golfo San Jorge south to the oil town of Caleta Olivia, with its huge central statue of an oil worker, then climbs inland. After 86km (53 miles), RN281 branches off RN3 for 126km (78 miles) to the coastal port of Puerto Deseado £ [map] , named after the Desire, flagship of the 16th-century English global navigator Thomas Cavendish.

Virtually unknown for many years, Puerto Deseado is the home base for a number of ships that fish in the western South Atlantic. It is beginning to develop as a tourist center, particularly for its rich coastal wildlife. There are sea-lion colonies at Cabo Blanco to the north, and Isla Pingüino to the south, of the bay, where you might see yellow-crested penguins and the unusual Guanay cormorant, and where spectacular black and white Commerson’s dolphins play with boats sailing in the estuary just outside the town.

Back on RN3, the next important stop is a pristine natural wonder, the Monumento Natural Bosques Petrificados $ [map] , just 80km (50 miles) to the west of the highway. This enormous petrified forest occupies over 15,000 hectares (247,000 acres). At the edges of canyons and mesas, the rock-hard trunks of 150 million-year-old monkey-puzzle trees stick out of the ground. Some trunks are 30 meters (100ft) long and a meter (a yard) thick – among the largest in the world. There are no overnight facilities at the park, and it closes at sundown, but there is a campsite with a store at La Paloma, 20km (12 miles) from the park headquarters.

Explorers’ traces

About 250km (155 miles) farther south on RN3 is the picturesque port of Puerto San Julián % [map] , also awakening to tourism, with several hotels and a small museum. Both Magellan (in 1520) and Drake (in 1578) spent the winter here and hanged mutineers on the eastern shore. Nothing remains there except a small plaque. Not far to the south of San Julián is the little town of Comandante Luis Piedra Buena ^ [map] , on the Río Santa Cruz, which was followed upstream by FitzRoy, Moreno, and other early explorers. Its main attraction is the tiny shack on Isla Pavón, occupied in 1859 by Piedra Buena, an Argentine naval hero. The island, on the river, is linked to the town by road bridge.

About 29km (18 miles) downstream lies the sleepy town of Puerto Santa Cruz, with its port, Punta Quilla, which is the base for ships that service the offshore oil rigs.

Río Gallegos

The capital of the province is Río Gallegos & [map] , some 180km (112 miles) south of Puerto Santa Cruz. It is a sprawling city of 100,000 on the south bank of the eponymous river, which has the third highest tides in the world, at 16 meters (53ft). At low tide, ships are left high and dry on mud flats. It is perhaps one of the most austere places in Argentina, and it is unlikely that you will want to linger here longer than you have to.

Moving southwest of Río Gallegos, RN3 enters Chile near a series of rims of long-extinct volcanoes. One of these, Laguna Azul, is a geological reserve, 3km (1.5 miles) off the main highway near the border post.

FACT

Many sheep farms in Patagonia are being bought out by large multinational enterprises, who buy most of their raw wool for processing abroad. Italian clothing magnate Luciano Benetton bought seven sheep farms in the region, totaling 20,000 hectares (50,000 acres).

Penguins and dolphins

Some 11km (6 miles) south of Río Gallegos, Ruta 1 branches southeast off RN3, over open plains to Cabo Vírgenes (129km/80 miles from Río Gallegos) and Punta Dungeness (on the border with Chile) at the northeast mouth of the Strait of Magellan. Here you can see Argentina’s second largest penguin colony, home to some 300,000 birds; visit the lighthouse; and perhaps watch dolphins just offshore. Near the cliffs are the meagre remains of Ciudad Nombre de Jesús, founded by the Spanish explorer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa in 1584. The road to Cabo Virgenes passes a couple of sheep farms: Estancia Cóndor, one of the larger estancias in the area, which is now owned by the Benetton family; and a few kilometers beyond that, Estancia Monte Dinero, which has a separate guesthouse for visitors and which also offers wildlife trips to the penguin colony at Cabo Virgenes.

Westward on Ruta Nacional 40

Western Santa Cruz province is spectacular but desolate. The main route through it is on RN40 – the longest road in the country, snaking its way up through the Northwest as far as the Bolivian border – and not a road to be taken lightly. Those who have traveled it from top to bottom are full of admiration for the rugged beauty of the country and are proud they have survived it. RN40 is not even accurately detailed on most maps, including those of the prestigious Instituto Geográfico Militar. The best one is the ACA (Automóvil Club Argentino) map of the province of Santa Cruz. In winter, some parts of the road may be inaccessible.

Ruta 40.

Yadid Levy

Southern RN40 is a difficult gravel road – rocky and dusty when dry, muddy when wet. Places marked on the map may consist of just one shack or may not exist at all. You must carry extra fuel and/or go out of your way at several places to refill. Sometimes small towns, or even larger ones, run out of gasoline and you may have to wait several days until a fuel truck comes along. In southwestern Patagonia there are gas stations only at Perito Moreno, Bajo Caracoles, Tres Lagos, El Calafate, and Río Turbio.

If you take any secondary roads, remember that there is no fuel available. You also need to carry spare tires, some food, and probably even your bed. There are few places to buy food or even a soft drink outside the larger towns. El Calafate is the main town of the southern Lake District, 313km (194 miles) from Río Gallegos. Halfway there is Esperanza, a truck stop with a gas station and roadside snack bar; nearby is Estancia Chali-Aike, which takes paying guests. Most of the drive is past ranches over the meseta central, coming to a high lookout at Cuesta de Miguez, where the whole of Lago Argentino, the mountains and glaciers beyond, and even Mount Fitz Roy can be seen.

Stunning landscape near El Calafate, with Lago Argentino.

Yadid Levy

The southern Lake District: El Calafate

El Calafate * [map] , a town of about 22,000 people, nestles at the base of cliffs on the south shore of beautiful Lago Argentino, one of Argentina’s largest lakes. An airport constructed in 2000 receives direct flights from Buenos Aires and this is the jumping-off point for the surrounding area, particularly to the Parque Nacional Los Glaciares. On the eastern shore of Lago Argentino, at the edge of town, is Laguna Nimez, a small bird reserve (daily 9am–7pm), which is home to a variety of ducks, geese, flamingos, and elegant black-necked swans. Walking around the lake from here is tricky, however, as the ground is boggy and crisscrossed with wide streams. Accommodations range from campsites and a youth hostel to elegant hotels. There are several tourist agencies and a number of good restaurants. Large tour groups do the circuit – Buenos Aires, Puerto Madryn, El Calafate, Ushuaia, Buenos Aires – every week.

Traveling 51km (32 miles) west of El Calafate, along the south shore of the Península Magallanes, brings you to the Parque Nacional Los Glaciares ( [map] , one of the most spectacular parks in Argentina. The southern Patagonian icecap, which is about 400km (250 miles) long, spills over into innumerable glaciers, which end on high cliffs or wend their way down to fjords. Just beyond the Península Magallanes, you can cross Brazo Rico in a boat for a guided climb on the Unesco World Heritage Site of the Perito Moreno glacier. A few kilometers on, the road ends at the pasarelas, a series of walkways and terraces down a steep cliff, which faces the glacier head on. It is a magnificent sight, especially on a sunny day. Visitors line up along the walkways, cameras at the ready like paparazzi at the Oscar awards ceremony, waiting for a chunk of glacier to calve off into the water with a resounding thunderous crack. To get even closer to the glacier, take one of the regular boat tours that leave from the nearby pier and which get you almost within touching distance of the ice wall.

Perito Moreno glacier.

Yadid Levy

The Perito Moreno glacier advances across the narrow stretch of water in front of it until it cuts off Brazo Rico and Brazo Sur from the rest of Lago Argentino. Pressure slowly builds up behind the glacial wall until, about every three to four years, the wall collapses dramatically and the cycle begins again. The glacier has not advanced since 1988, however, leading scientists to question whether global warming is to blame: 90 percent of the world’s glaciers are retreating. Old water levels can be seen around these lakes. Hiking too near the glacial front is prohibited because of the danger from waves caused by falling ice.

Upsala glacier

The second major trip from El Calafate is a visit to Glaciar Upsala, at the far northwest end of Lago Argentino. Boats leave every morning from Punta Bandera, 40km (25 miles) west of El Calafate. In early spring, they cannot get near Upsala because of the large field of icebergs, so may visit Spegazzini and other glaciers instead. Some trips stop for a short walk through the forest to Onelli glacier. On the way back, stop at Estancia Alice, on the road to El Calafate. Asados (barbecues) and tea are available here, and shearing demonstrations are held in season. You may also see black-necked swans and other birds.

It is only a short distance across the Sierra Los Baguales from Parque Nacional Los Glaciares, Argentina, to Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, in Chile. From some spots near El Calafate, the Paine mountains can be seen. But there is no road through. Instead, you must backtrack to Puerto El Cerrito (at least that section is paved) and then take RN40 again west and south to enter Chile either at Cancha Carrera or farther south at Río Turbio. You can also fly back to Río Gallegos and fly on to Punta Arenas, in Chile, from where it is still a seven-hour drive north to the Paine National Park.

El Chaltén and Monte Fitz Roy

Returning north, up RN40 from El Calafate, at the far northern end of the Parque Nacional Los Glaciares are some of the most impressive peaks in the Andes, including Cerro Torre (3,128 meters/10,263ft) and Monte Fitz Roy (3,406 meters/11,175ft). In good weather Fitz Roy can be seen from El Calafate. The sheer granite peaks attract climbers from all over the world, who describe their experiences in the register at the northern entrance to the park.

The best base for visiting this part of the national park is the village of El Chaltén ‘ [map] , some 219km (136 miles) north of El Calafate, via a well-paved stretch of RN40 above the western end of Lago Viedma. The village – whose name means “blue mountain,” the Amerindian name for Fitz Roy – nestles in a hidden bowl at the foot of the mountain, with its glacier coming down off the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. Founded in 1985, this once tiny village has expanded rapidly in recent years due to its ever-growing popularity with visiting trekkers and mountain climbers (though it virtually closes down in winter). It has a national park information office, food and souvenir stores, and a gas station. There is a range of accommodations available, including holiday bungalows, hostels, and basic campsites. In summer, there are two daily buses from El Calafate.

Continuing north on RN40, at Tres Lagos, Ruta 31 leads northwest to Lago San Martín (called Lago O’Higgins in Chile). Estancia La Maipú is situated on the south shore, offering accommodations, horseback riding, and trekking.

About 560km (348 miles) north of El Chaltén, the northwesternmost town in Santa Cruz province is Perito Moreno, a dusty place with little to offer. From here, however, a paved road leads 57km (35 miles) west to the small town of Los Antiguos, on the shore of Lago Buenos Aires. Small farms here produce milk, honey, fruit, and vegetables; the town has a couple of hotels and a campsite. A mere 3km (1.5 miles) to the west, you can cross the Chilean border to the town of Chile Chico and other scenic areas near the Río Baker.

Cueva de las Manos

South of Perito Moreno is the Cueva de las Manos (Cave of the Hands), a national historical monument and World Heritage Site located in a beautiful canyon 56km (35 miles) off RN40 from just north of Bajo Caracoles. Pre-Columbian cave paintings are found all over Santa Cruz, but those at Cueva de las Manos are the finest. The walls here are covered by paintings of hands and animals, principally guanacos (relatives of the llama), which are thought to be anything between 3,000 and 10,000 years old. Numerous lakes straddle the Argentine–Chilean border in this region. RN40 lies well to the east of the mountains. Any excursions to the lakes to the west, such as Lago Ghio, Pueyrredón, Belgrano, and San Martín, must be made along side roads; there are no circuits – you must go in and out on the same road. The road to Lago Pueyrredón leaves from Bajo Caracoles.