1 |

Africa |

A Geographic Frame |

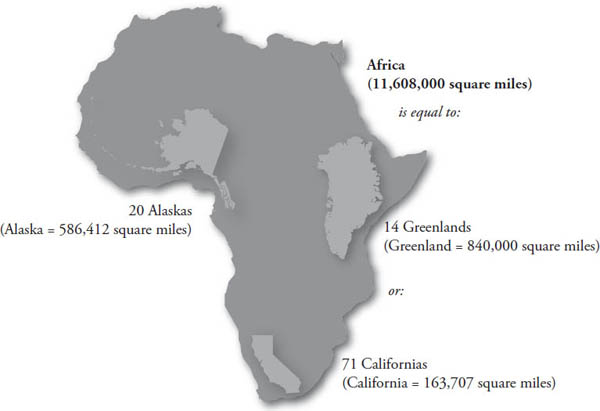

Africa is a continent, the second-largest after Asia. It contains fifty-four countries, several of them vast. Each of Africa’s biggest countries—Algeria, Congo, and Sudan—is about three times the size of Texas, four times that of France. Africa could hold 14 Greenlands, 20 Alaskas, 71 Californias, or 125 Britains. Newcomers to the study of Africa often are surprised by the simple matter of the continent’s great size. No wonder so much else about Africa is vague to outsiders.

This chapter introduces Africa from the perspective of geography, an integrative discipline rooted in the ancient need to describe the qualities of places near or distant. The chapter begins by examining how the world’s understanding of Africa has developed over time. Throughout history, outsiders have held a greater number of erroneous geographic ideas about Africa than true ones. The misunderstandings generated by these false ideas have been unhelpful and occasionally disastrous. After this survey of geographic ideas, the chapter settles into a general preference for what is true, probing, in turn, Africa’s physical landscapes, its climates, its bioregions, and the way that Africans over time have used and shaped their environments. A final section outlines the difficulties Africa has confronted and the betterment Africans anticipate as they integrate ever more fully and fairly with emerging global systems.

Knowledge of geography is a frame for deeper inquiry in all fields because the qualities of place shape every human endeavor. Anyone striving to understand the challenges and potentialities that citizens of African countries have to work with in their struggle to obtain for themselves and their families the security and prosperity that is their birthright would do well to reflect regularly on Africa’s geography. A map, especially one’s own emerging mental map of Africa, is an excellent organizing tool. It structures information according to the fundamentally interesting question “Where?” It is a solid place to start any journey, including one’s personal passage toward a more nuanced understanding of Africa.

Map 1.1. The Size of Africa.

Places are ideas. Consider, for example, that most significant of places, home. Every home is a physical entity—it exists concretely—but the meaning of home, its reality, is all tied up in the experiences and emotions of the people who live in that place or otherwise know it. Or consider Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh is a particular collection of buildings, roadways, rivers, people, and a great deal else occupying a defined portion of western Pennsylvania, but it also is an idea. More correctly, it is a set of ideas, because each of us has a different sense of Pittsburgh based on our views of cities in general and whatever memories and associations, accurate and false, Pittsburgh as place or word conjures in our minds when we encounter it. So too Africa. Though without doubt a continent, Africa, like all continents, also is a complex of ideas that have flowed through the human imagination, accurately and fancifully, generously and carelessly, over a great span of time, giving rise to many meanings and actions, some grounded in truth and noble, others based in error and unfortunate.

If Africa is a continent but also a product of the human imagination, the first question that must be asked is when it originated. Physical Africa, the continental landmass, is easy to date. Any basic geology text will describe how Africa took shape after the breakup and drifting apart of the pieces of the supercontinent Pangaea about 180 million years ago. As for the idea of Africa, it is somewhat more recent. The idea of Africa came into being over the last two thousand years, and it did so largely in Europe. The fact that the idea of Africa developed mostly in Europe goes a long way toward explaining how Africa is conceived worldwide, even now.

This claim—that Europeans were largely responsible for the idea of Africa—is easy to substantiate and does not discredit Africa and its people. Europeans invented America too, just as Chinese invented Taiwan and Arabs the Maghreb. All through world history, at scales ranging from the continent to the community, outsiders have given identities to places. A common way this happens is by first naming. There were no Native Americans, only hundreds of distinct peoples such as the Ojibwa of the Great Lakes and the Navajo of the western desert, until Europeans crossed the Atlantic five hundred years ago and announced the existence of a continent to be called America. Another way outsiders give identity to place is by inspiring or provoking, sometimes by threat or aggression, unity and regional loyalty where none existed before. There was no Germany until Bismarck, around 1870, convinced the German-speaking principalities of central Europe that they were one and that joining Prussia to form an entity called Germany would be in the interest of all.

Even though few early Africans knew the bounds of the continent or could imagine Africa as a whole (the same can be said of early people on all of the continents), there were exceptions. One interesting case comes down to us from the Greek historian Herodotus, who in the fifth century BCE (Before the Common Era) wrote a brief but tantalizing report of a sea journey by Phoenicians, organized by King Necho II of Egypt, around the landmass we call Africa (which Herodotus called Libya), undertaken about two hundred years before Herodotus’s time. While no other evidence of this expedition survives, it is pleasant and plausible to believe that it occurred. If it did, then at least one small group of Africans, probably a few Phoenician adventurers from Egypt, learned of the entirety of the African landmass as long as twenty-seven hundred years ago. This knowledge appears to have died with them. It did not lead to any mapping or broad understanding within Africa of the continent’s extent. Even Herodotus knew next to nothing about what those sailors saw; he only reported the legend of their trip.

Map 1.2. The World According to Herodotus (ca, 450 BCE).

An African Circumnavigation of Africa 2,700 Years Ago

Here is the entirety of Herodotus’s account of an African circumnavigation reported to have occurred two hundred years before his time. The charming anecdote at the end, noting the strange position of the sun, inspires confidence in the story’s factuality because, unknown to Herodotus, sailors heading west at the latitude of southernmost “Libya” would see the sun on the starboard (right) side of the ship (i.e., in the northern sky) all day long, just as in Europe and most of North America the sun’s daily passage from east to west occurs entirely in the southern sky.

Libya is washed on all sides by the sea except where it joins Asia, as was first demonstrated, so far as our knowledge goes, by the Egyptian king Necho, who, after calling off the construction of the canal between the Nile and the Arabian gulf, sent out a fleet manned by a Phoenician crew with orders to sail west about and return to Egypt and the Mediterranean by way of the Straits of Gibraltar. The Phoenicians sailed from the Arabian gulf into the southern ocean, and every autumn put in at some convenient spot on the Libyan coast, sowed a patch of ground, and waited for next year’s harvest. Then, having got in their grain, they put to sea again, and after two full years rounded the Pillars of Heracles in the course of the third, and returned to Egypt. These men made a statement which I do not myself believe, though others may, to the effect that as they sailed on a westerly course round the southern end of Libya, they had the sun on their right—to northward of them. This is how Libya was first discovered by sea.

—Herodotus, The Histories 4.42 (ca. 425 BCE)

Translated by Aubrey de Selincourt

European ideas about Africa began to take shape during the period of classical antiquity. The ancient Greeks and Romans had a great deal of solid knowledge about the nearer parts of Africa. After the Roman defeat of Carthage (in present-day Tunisia) during the Punic Wars of the second century BCE, the Roman Empire expanded to encompass much of the continent’s northern reaches. The cultural and economic ties between Rome and its African provinces were strong. Northern Africa quickly became known as the granary of the empire. The word “Africa” dates from this era. It possibly comes from “Afer,” which in the Phoenician language was the name for the region around Carthage. According to this theory, Roman geographers, needing a word for the landmass to the south, borrowed “Afer,” Latinized it, and broadened its application to the entire continent south of the Mediterranean (much as Herodotus had used “Libya” in the same way, for the same purpose, a few hundred years before).

Commerce has linked Africa with the rest of the world for the last two thousand years. Never was Africa entirely isolated from the main currents of global interaction and trade. Roman coins and artifacts from the second and third centuries of the Common Era (CE) have been unearthed in lands south of the Sahara, evidence that Africa’s great desert was traversed occasionally in early days. Sailors and settlers from Borneo and Sumatra, in present-day Indonesia, traveled to Africa beginning about 350 BCE. Their descendants and language dominate Madagascar today, and the crops that these settlers carried from Southeast Asia, such as plantain, became dietary staples all across continental Africa. As early as the seventh century CE, Persian and Arab traders established outposts up and down Africa’s Indian Ocean coast, drawing commerce from the interior, linking producers in eastern and central Africa through trade with the Middle East and the wider world. There are clear records by the fourteenth century of voyages by imperial Chinese trading vessels carrying silk, porcelain, and other goods from the ports of Asia to the East African coast. The Christian kingdom of Ethiopia exchanged emissaries with the courts of Europe, including the Vatican, in the fifteenth century. And many Africans traveled great distances within the continent and beyond. A good example is Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta, commonly known as Ibn Battuta, a fourteenth-century Moroccan adventurer who voyaged all across the northern third of Africa and eventually as far as China and Southeast Asia, reporting his discoveries in Arabic manuscripts read throughout the Muslim world.

These contacts of non-Africans with Africa, and the rich descriptions of portions of Africa provided to the world by outsiders and African writers such as Ibn Battuta, were elements of a partial geography of Africa. Yet an accurate cartography—a map of the continent’s position, size, and proportions—awaited the voyages of European seafarers during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and their transmittal of information to European mapmakers capable of accurately rendering Africa’s outline. In other words, despite early knowledge of many parts of Africa in many lands, including Europe, China, and the Middle East, and of course among every African who ever lived, the definition of Africa as a whole, its description as a geographic totality, fell to Europeans. And this made all the difference. Europe was poised in 1500 to rise to global dominance. The accurate and inaccurate ideas that Europeans began attaching to their categorical creation, Africa, spread around the world with European power.

What of these ideas? What did Africa come to mean in the European imagination? Portrayals of Africa and Africans in the literature and art of Europe before 1500 or so, though hardly widespread, were largely benign. That is, until about five hundred years ago European intellectuals appear to have known little about Africans (only a few people from Africa would appear now and then in the cities of Europe), and less still about Africa as a continent, but when they did consider Africa and Africans it was with a rough sort of equality. This is not to say that Europeans harbored no fantastic ideas about Africa, but their fantasies were not very much different from those constructed about many unknown lands: rumors of dragons, giants, astonishing creatures, and strange physical and cultural variations of the human family populating regions that were unbearably hot and forbidding. These were ancient motifs, long ascribed in many cultures to unfamiliar places. But Africa in Renaissance Europe was not deemed particularly backward, primitive, or frightful. In paintings Africans usually were depicted as simply another shade of human being. They were sometimes a point of interest in a picture, but no malign attention was drawn to them. Physical exaggerations or contortions were not seen. Nor in European writing of this time do we see much overt anti-African racism, only the kinds of physical and cultural speculations that were applied to unfamiliar people from all unexplored or unknown areas.

An African Description of the Nile in 1326

Ibn Battuta, a fourteenth-century Moroccan adventurer, is the most celebrated and widely read African traveler of all time. He wrote in Arabic, at great length, of his travels in Africa and all over the known world.

The Egyptian Nile surpasses all rivers of the earth in sweetness of taste, length of course, and utility. No other river in the world can show such a continuous series of towns and villages along its banks, or a basin so intensely cultivated. Its course is from South to North, contrary to all the other great rivers. One extraordinary thing about it is that it begins to rise in the extreme hot weather at the time when rivers generally diminish and dry up, and begins to subside just when rivers begin to increase and overflow. The river Indus resembles it in this feature. The Nile is one of the five great rivers of the world. . . . All these will be mentioned in their proper places, if God will. Some distance below Cairo the Nile divides into three streams, none of which can be crossed except by boat, winter or summer. The inhabitants of every township have canals led off the Nile; these are filled when the river is in flood and carry the water over the fields.

—From Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta,

Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354

Translated and edited by H. A. R. Gibb

(London: Broadway House, 1929)

Living standards in Europe and Africa five hundred years ago were little different. On both continents nearly everyone lived off the land, most in agriculture. Diet was unvaried. Hunger was common. Life span was short. Almost no one on either continent was well educated. Why should Europeans have considered Africans, five hundred years ago, to be in any manner inferior? There was no material reason for Europeans to stigmatize Africa and Africans in particular at this time, and generally they did not.

This changed. Increasingly in written descriptions and paintings from Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Africans took on qualities that are familiar to us now. Africans came to be defined by Europeans as poor, uneducated, technologically unsophisticated, underdeveloped, and non-Christian.

Why did this happen? Why, about five hundred years ago, did Africa in the European mind go from being a somewhat mysterious but not fundamentally different assortment of peoples and cultures to being the anti-Europe, the antithesis of everything that made Europe great?

One reason was that standards of living, technology, education, and knowledge were rising in Europe, lifting many people (though far from all) above the levels of basic subsistence that had long been their lot. People living in vibrant economies often lose interest in the rest of the world except to the extent that it can supply what they desire. Certainly Europe’s economic progress is part of the story. But the main reason for Europe’s emerging negative view of Africa was the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which started in a major way in the 1500s and rose to its height over the next two hundred years.

This is not the place to dwell at length on the slave trade, but this much must be said: from the 1500s to the 1800s, European slave traders transported millions of Africans from the shores of the continent to work in European colonies in the New World. Slavery was an ancient and nearly universal human institution long before the beginning of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but the world had never seen anything like this, with so many millions of people pulled from their homeland in a sustained and organized fashion and sent to the far ends of the earth purely for the economic advantage of well-off Europeans. How could this commerce possibly be justified morally and psychologically? Europeans did so by convincing themselves that Africa was populated by people who did not warrant the concern one might have for others.

As the slave trade ratcheted up, the idea spread quickly around Europe that Africans were not part of our common humanity. Did everyone in Europe during the period of the slave trade think about or firmly believe these ideas? Certainly not. Africa and Africans were quite tangential to the lives of most Europeans. But to the extent that Europeans thought at all about Africa and Africans in early modern times, racist assumptions of African inferiority became the default. Much later, in the nineteenth century, these theories of racial inferiority were elaborated and developed into a pseudoscience, but the roots of anti-African racism are here, in the rise of the slave trade in early modern Europe and the need in Europe and eventually the Americas for a moral and psychological crutch to support it. The trade endured for more than three hundred years. Ideas of inferiority, once embedded, lasted longer than that.

A whole set of negative qualities began to be attributed to Africa and Africans to set them apart from Europeans. These qualities were oppositional: if we are white, they are black; if we are good, they are bad; if we are Christian, they must be immoral; if we are sophisticated, they must be primitive; if we are enterprising, they must be lazy; if we are cerebral, they must be physical; if we are moral, they must be licentious; if we are orderly, they must be chaotic; if we are a people capable of self-governance, they must need our help. We live with this legacy. About the realities of Africa—as opposed to the imagined qualities of Africa’s people, land, economies, and political geography—the West knew little until the twentieth century.

What about African ideas of Africa? When did Africans discover and begin to form thoughts about the continent? This is not an absurd question. As noted already, the geographic category of “Africa” arose in Europe, and almost no one anywhere, including Africa, had any knowledge of the extent of the African landmass until the fifteenth century. Thus there is a history of African ideas of Africa, just as there is a history of Western ones. It starts with the slave trade.

Throughout the slave trade period and continuing after it ended, a trans-Atlantic discourse linked intellectuals in Africa to communities of African descent in the Americas. In these communities—in North America, South America, and the Caribbean—a continental perspective on Africa developed early because slaves and their descendants needed a unitary sense of Africa, a conception of Africa as a whole, for their identity and their dignity. After all, people from many corners of Africa were enslaved but as the years passed most knowledge of a family’s precise roots in Africa was lost. Adult captives who survived the trans-Atlantic journey certainly knew from where in Africa they had been taken, and sometimes this knowledge persisted through a few generations, passed down from parents to children, often as a scrap of information, perhaps just a word for some now unknown village or kingdom. But even these tidbits tended naturally to fade over time. Eventually most people in the New World whose forebears had been transported as slaves knew nothing whatsoever of the origins in Africa of their various ancestors. They knew not whether they were descended from Hausa, Wolof, Yoruba, or Ewe people (or from what mix of different African ethnicities), but they did know that their people had come from Africa. It was in this context of definitional necessity, largely in the Americas after the sixteenth century, that people first began to conceive of themselves as being of essentially African origin and to think of the totality of Africa as a place, their ancestral home.

This continental understanding spread around communities of African descent all over the Atlantic world, and soon (because the Atlantic was an information highway, not a barrier) it became part of the thinking of traders, scholars, political leaders, and other cosmopolitans in Africa itself. The idea of the African continent as a generalizable place, a place inhabited by black people sharing many commonalities (not least the racism and bondage imposed on them for centuries by Europeans), people united in their history with slaves and the descendants of slaves in the Americas, came to be called, in the nineteenth century, Pan-Africanism.

Pan-Africanism still has wide ideological currency today. It is the idea that there is an essential unity to all of Africa, a unity of race, a unity forged through the experience of racism, enslavement, and nineteenth- and twentieth-century European colonialism, a unity that binds all Africans and people of African descent around the world in a community of shared history, oppression, and liberation challenge. This discourse of Pan-Africanism shaped nineteenth-, twentieth-, and even twenty-first-century ideas within Africa about the relevance of the continent as a category of experience. Without pan-Africanism people in Africa might not have come so readily to identify themselves as, yes, Igbo, Kikuyu, or Hausa, and, yes, Nigerian, Kenyan, or Congolese, but also as African. All of this is to say that Africa may have been a European categorical creation, but people in Africa had a greater incentive than anyone else to take a continental view, and by the nineteenth century many Africans, especially the educated elite, did just this, largely in opposition to Europe.

So places are ideas, continents are inventions, and Africa is what people have imagined it to be. History shows again and again that what people think about a place, true or not, matters more to the actions they take than does any combination of uncontestable facts. Yet factual knowledge, including accurate geographic information about a place, generally produces better results.

About Africa’s physical landscapes only a little needs to be said. While the continent presents many spectacular features and splendid views, it is not, on the whole, a land of sharp transitions. A driving trip of several days in most parts of Africa impresses the traveler as would a similar trip in west Texas or Saskatchewan: the scale of the land is immense, but the landscape variations are subtle.

The major exception to Africa’s general landscape regularity is the mountainous east and south. Some geographers helpfully distinguish between “high Africa,” extending from Ethiopia all the way south along Africa’s eastern side to the Cape of Good Hope, and “low Africa,” the vast rolling plain encompassing nearly all of the rest of the continent. Africa’s highest peaks—Mt. Kilimanjaro and Mt. Kenya—are in high Africa. Patterns of human livelihood in the east and south always have been strongly influenced by the height of land and the productive volcanic soils found there. The mountainousness and ancient volcanism of the east are closely related to the other prominent landscape feature of this part of Africa: rift valleys. From the Red Sea through central Ethiopia, Kenya, and into Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique, great fissures in the earth form long, steep-sided north-south valleys, some partly filled by waters of great lakes, all resulting from the same tectonic processes that have, over eons, thrown up the adjacent highlands.

Map 1.3. High Africa, Low Africa, and the Major Rivers.

Even low Africa has some mountains, including the Atlas range of the far northwest, and Mt. Cameroon, one of Africa’s highest peaks, only a short distance from the Atlantic Ocean, in the country that bears its name. In general, though, low Africa is flat to undulating. Here are most of Africa’s immense rain forests, its expansive savannas, and its greatest desert.

African soils are varied, but in general their productivity suffers from the continent’s tropical position and from the absence of vast alluvial plains such as those of India, Bangladesh, and China. On other continents, where rivers rise in nutrient-rich uplands such as the Andes, the Himalayas, or the Tibetan Plateau and then cross gently sloping land to the sea, they deposit their sediments on ever-expanding alluvial plains, building up soils of great depth and fertility. With partial exceptions in Egypt, Nigeria, and Mozambique, Africa has none of this. Its great rivers—the Nile, the Volta, the Niger, the Congo, the Limpopo, and the Zambezi—rise in nutrient-poor zones and thus carry relatively unproductive sediment, or flow so circuitously to the sea that much of what they do carry is deposited in dry inland regions unsuited to agriculture, or fall so steeply to the sea from the African plateau that their riches are washed to the depths (see map 1.3). As a result, Africa lacks great expanses of deep, river-deposited soils that give advantages to other lands, such as eastern China, Bangladesh, and the Indus Valley of India and Pakistan.

Figure 1.1. Near the Ahaggar mountains of southern Algeria.

Jeanne Tabachnick.

Fertile deltas aside, tropical regions generally contain poor soils. Africa, the most tropical of continents, bears a particular burden in this regard. In Africa’s humid tropics, where it is hot year-round and moisture is abundant, thriving soil microorganisms quickly break down organic matter such as dying plants and fallen leaves and branches. Nutrients liberated by this rapid decomposition cycle without delay from the ground up through the vascular systems of trees and other long-lived plants, and there they stay—as leaves, bark, and wood—until released again to the ground by death. In other words, nutrients in humid tropical systems are plentiful but fixed in the forest canopy, not in the soil, where most agricultural crops can use them. The challenge to farmers in these systems is to get nutrients from the canopy into the earth, where their crops can benefit from them.

Large parts of Africa are tropical but seasonally dry, and here the soil challenge is different. Soil development in the drier tropics is hampered by a lack of organic matter (because year-round high heat and moisture deficits during a long dry season limit plant growth) and by the baking and chemical hardening of ground that occur in the seasonal absence of rain under relentless sun.

Figure 1.2. Rainforest near Mounana, Gabon.

Africa does have zones of excellent soils, such as the slopes of ancient volcanoes near the rift valleys of East Africa, and nowhere is the soil situation impossible. Africans have made their living from agriculture for a very long time, longer than people have done in parts of Europe. Soil quality is a particular challenge to African food producers, but the continent’s soils are by no means an insurmountable obstacle to food security and prosperity. Africa’s physical endowment is more than sufficient for all Africans to thrive.

Africa is incomprehensible without a basic understanding of climate and the patterns of life that variability in temperature and rainfall yield. Temperature is straightforward. The equator bisects Africa, and equatorial regions receive relatively direct as opposed to relatively indirect solar radiation during most of the year; thus most of Africa experiences high year-round heat.

There are exceptions to this general rule. In Africa north of the Sahara, the narrow strip of land bordering the Mediterranean Sea, temperatures are similar to those in Mediterranean Europe: high heat during much of the year but cooler weather from December until March. Likewise, much of southernmost Africa—the Republic of South Africa and adjacent countries—experiences a distinct cool season, but with opposite polarity: here it is cool from June until September. Some snow occurs at high elevations every year in Africa’s far south, just as it does in the Atlas Mountains of the north.

A third exception to the general rule of high year-round heat is in highland areas anywhere. In high Africa—from Ethiopia through Kenya and Tanzania all the way south to the Cape—altitudes greater than 1,500 meters (5,000 ft.) above sea level are common. At this elevation, even in the tropics, air temperature is likely to be cool some of the time. The high slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain, are glaciated, as are those of Mt. Kenya (though global warming is rapidly diminishing these and all other tropical glaciers). Average temperatures on these peaks are close to freezing. People do not live on the heights of Africa’s great mountains, but they do live in Nairobi, 1,600 meters (5,300 ft.) above sea level. In Nairobi, as in many parts of high Africa, daytime temperatures during some months hover around 20°C (68°F), far from hot.

A final exception is in desert regions. Here there are great diurnal fluctuations in temperature: high heat during the day but great cooling at night. Nighttime temperatures in Africa’s deserts frequently drop to 10°C (50°F) or lower.

Precipitation in Africa is much more varied than temperature. It is also more complicated and more important to understanding the realities of African life. Variability of rainfall across territory and over the course of every calendar year largely explains patterns of plant and animal types and abundance and the ecological situations that have conditioned the diversity of Africa’s human cultural forms.

The processes responsible for rainfall patterns in Africa are complex in detail but simple to understand in a three-part model:

1. Equatorial low pressure. Along the equator, where the daytime sun is directly overhead (or nearly so), solar radiation passes through a minimum of filtering atmosphere. Intense radiation striking the earth’s surface generates a great deal of heat. The highest heat of all is along the equatorial belts of continents because the sun heats absorptive land more readily than reflective seas. Because hot air rises, all across equatorial Africa air warming near the earth’s surface rises into the atmosphere. To take its place, air masses rush toward the equator from the north and south, including moist air masses from over the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. These inrushing air masses also heat up and rise, becoming part of an equatorial low pressure vortex. This hot, moist air rising along the equator cools as it rises. As air cools, its capacity to hold moisture declines, and so it rains. For these reasons, equatorial Africa, except for portions of the mountainous east, is rainy nearly year-round.

2. Subtropical high pressure. Air rising at the equator and cooling in the atmosphere must flow somewhere. It does flow—at high elevation—toward the north and south. This poleward-streaming air in the upper atmosphere begins to sink back toward earth at 20–40 degrees north latitude and 20–40 degrees south latitude (map 1.4). As it sinks toward the earth’s surface, which is heated by the sun, this air warms. As air warms, it can hold more moisture. Rain is highly unlikely under these conditions. So in two belts influenced by this sinking air (in other words, by subtropical high pressure)—north of about 20° north latitude and south of about 20° south latitude—Africa is dry.

Map 1.4. Generalized Atmospheric Circulation in the Tropics: The Conditions That Bring Rain.

3. Seasonality. If parts 1 and 2 provided a fully accurate account, they would describe a straightforward pattern of rainfall in Africa: heavy rains in an equatorial band about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) wide, declining rain toward the north and south, and eventually, at roughly 20°-30° north and south latitude, no rain at all. However, parts 1 and 2 neglect a major complication: that the earth revolves around the sun at an angle. Only in March and September is the sun directly overhead at the equator. On June 21 it is overhead at the Tropic of Cancer and on December 21 at the Tropic of Capricorn (see the bottom of map 1.4). Thus, the low pressure belt described in part 1 as “equatorial” in fact shifts north of the equator in summer and south in winter. The two belts of subtropical high pressure shift with it. Consequently, much of Africa experiences extreme rainfall seasonality: high rainfall when the belt of low pressure centered on the equator moves seasonally in, and almost no chance of rain when it shifts out and is replaced by high pressure. The movement north and south from equatorial Africa of this rain-bearing belt of low pressure (sometimes called the “inter-tropical convergence zone,” or ITCZ) is somewhat variable from year to year but predictable in broad outline. It moves northward with the sun in the months around June and southward with the sun in the months around December. The rainy season is longest, and annual rainfall totals are highest, in areas that are under its influence for most of the year. The rainy season is shortest, and rainfall totals lowest, in areas it reaches only briefly.

Map 1.5 shows average annual rainfall totals in Africa. Though there are a few anomalous regions (notably in the east, where other processes serve as complicating factors), the model outlined above explains the map’s patterns well. Where low pressure conditions prevail for most of the year, rainfall totals are high. Where the ITCZ reaches only briefly, totals are low. Northern Nigeria, for instance, receives only about 600 mm (24 in.) of rain per year because low pressure conditions bringing rain last only from about May through September. During the rest of the year, high pressure prevails and there is rarely a cloud in the sky.

Also delineated on map 1.5 are basic climate zones. In tropical Africa (which is the entire continent except the far north and far south) there are four important zones:

• Humid tropical Africa. Rain occurs nearly year-round. If there is a dry season, it lasts only a month or two. The average annual rainfall total is greater than 2,000mm (roughly 80 in.).

• Sub-humid tropical Africa. The rainy season lasts six to ten months; 1,000–2,000mm (40–80 in.) of rain falls in an average year.

• Semi-arid tropical Africa. There is a distinct rainy season, but it lasts less than six months, in some areas as few as two or three months. Average rainfall totals are between 200 and 1,000mm (8–40 in.).

• Arid tropical (or dry) Africa. There is little to no rainy season. In the driest parts of the arid tropics, years may pass without appreciable rain. The annual average rainfall total is less than 200mm (8 in.).

Map 1.5. Average Annual Rainfall and Climate Zones.

Map 1.6 is a map of Africa’s principal biomes, or biological regions. The biomes are defined by the putative natural vegetation that would occur in the absence of agriculture and other human modifications (although, as we will see in the next section, on human use and transformation of the environment, this distinction is problematic). The close correspondence between rainfall shown in map 1.5 and vegetation shown in map 1.6 is unsurprising. Africa’s humid tropical lands support rain forest. The arid tropics are desert. Between the extremes of rain forest and desert we see gradations of Africa’s most characteristic biome, tropical savanna.

A savanna is a grassland studded with trees, but not all tropical savannas are alike. The savannas of sub-humid areas often are labeled “woodland savanna.” Here the trees may grow quite large and are relatively closely spaced, though not so dense that they impede the growth of grasses underneath. The savannas of semiarid Africa are often called “shrub savanna.” In these zones the trees are generally smaller and more widely spaced; grasses predominate, though they typically die back during the long dry season.

Map 1.6. Major Biomes.

As map 1.6 shows, savannas cover large parts of Africa. They encompass much of the continent’s best agricultural land and many of its most populated areas. In a great many African societies, therefore, people have learned to calibrate food production calendars and myriad other aspects of cultural life to the rainfall seasonality so characteristic of tropical savanna regions—regular cycles of plenitude and parching—much as people in temperate regions such as Europe and North America adjust their production calendars and other aspects of their lives to the temperature seasonality of winter and summer.

Some of Africa’s biomes have common English names. The central African rain forest is usually called just that, but by common convention we give formal names to deserts. The main deserts of Africa are the Sahara, the Kalahari, and the Namib. Only one of Africa’s savanna belts has a formal name, the Sahel, the dry, shrub savanna just south of the Sahara. This name comes from the Arabic word for “margin” or “shore,” in this case the southern margin of the Sahara. Countries that encompass large parts of this biome sometimes are called the Sahelian countries: Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, and Sudan.

Map 1.7. Countries of Africa and Selected Cities.

It is tempting to divide the history of Africa into three grand epochs—precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial—and to generalize about the human use and transformation of nature in each. This temptation should be resisted. The three-period view of African history, though common, is absurd. The colonial period refers to the years when most of Africa was occupied and controlled by several European powers, the 1880s until the 1970s, a span of ninety years. The postcolonial period encompasses the few decades since then. And the first period, the precolonial period, covers two hundred thousand or more years stretching back into the primeval past, to the time when Homo sapiens first appeared on the planet. This is like dividing the calendar year into three parts, December 31, December 30, and pre–December 30: the periods wildly lack analytic equivalence and contort our thinking about Africa by tacitly suggesting that before colonialism not much happened. True, some of the first period could easily be labeled “prehistoric” instead of “precolonial,” but relabeling does not solve the problem, and in any case there is no general agreement about where on Africa’s timeline prehistoric gives way to precolonial.

Figure 1.3. In the Sahara of southern Algeria.

Jeanne Tabachnick.

Human history in Africa is almost incomprehensibly long. We now know for certain from genetic as well as archeological evidence that our species evolved in Africa between 150,000 and 250,000 years ago from earlier primate species that no longer exist, and that for most of this immense expanse of time humanity lived only in Africa. People did not push permanently out of Africa until a migration event about sixty thousand years ago, after which our species spread worldwide. We are all African by origin.

Because people have lived in Africa for so long, the concept of “natural environment” is a particular problem there. More than anywhere else, people and nature in Africa have co-evolved. Through millennia, through climate shifts that have shuffled the biomes, people have been adjusting to different African environments, molding them, living, working, taking from the earth, burning, cutting, hunting, planting, nurturing, and destroying; all environments in Africa are natural only in the sense that people are a part of nature. The major biomes of today’s Africa are real, but many of their qualities come from a quarter of a million years of human use.

Our first impacts on nature in Africa were as hunter-gatherers. For most of human history the only economic activity was hunting and gathering, also known as foraging. It prevailed in all biomes, from deep forest to desert, and it persisted into the present century, though barely. Forager population densities were always low. People lived in small mobile bands, moving across the landscape to take advantage of game and desired wild plants where they were abundant, abandoning areas where resources had been temporarily depleted. Despite being sparse on the land, our African foraging ancestors were entirely capable of altering plant and animal communities. Rarely if ever did they live in benign equilibrium with the rest of nature. They burned grasslands and forests to drive game. They used poisons to take fish. They extirpated unwanted plant and animal species from their territories while intentionally promoting and protecting desirable ones. No people, not even hunter-gatherers, leave the earth entirely as they found it.

The decline of hunting and gathering as a subsistence strategy was long and gradual, beginning with the arrival of agriculture in parts of Africa about seven thousand years ago. Even as recently as three thousand years ago foraging may have supported the majority of Africans, but this way of life continued to decline to the point that it is inconsequential now. A very few societies dependent on hunting and gathering survived to the turn of the twenty-first century, many of them supplementing their foraging by trading with nearby farmers and herders, but in Africa today hunting and gathering are little different than in most of the rest of the world, including Europe and North America: an occasional pursuit enjoyed by a small number of mainly rural people who have other primary occupations, or the specialized craft of a few individuals or families living in communities whose economies are diverse.

Pastoral herding and agriculture arrived or were independently invented in the northern third of Africa about seven thousand years ago (i.e., about 5000 BCE). From the north these two economies spread across the continent, diffusing especially rapidly after about 1000 BCE. Herding economies are based on the tending of domesticated animals, in Africa mainly cattle, camels, goats, and sheep. Herding is most common in the savanna zones because cattle and sheep require grass for grazing, while camels and goats require low trees and shrubs for browsing. Any temptation by herders to move into forest regions was (and is) checked by poor ecological fit: the absence of grasses and shrubs and the presence of trypanosomiasis, a fatal livestock disease spread by the tsetse fly, endemic in Africa’s wetter areas.

Like foragers, Africa’s herding peoples always have lived in low concentrations; their economy cannot support high population densities. Yet they occupied (and still do occupy, for this way of life, though rapidly declining, is still with us) vast tracts of Africa’s shrub and woodland savanna. Here they move cyclically over the course of the year, knowing where in each season to obtain water and forage for their livestock, and where to trade animal products with farmers for grain.

Pastoral herders have modified Africa’s savanna landscapes by intentionally and unintentionally altering the mix of plant species in a region, sometimes following practices that conserve and encourage the growth of grasses and shrubs that their livestock prefer and at other times (especially during drought years) overusing and thus diminishing them. Drought is a particular threat to herders because so much of their land is semi-arid and prone to periods of low rain. Herders usually respond to drought by concentrating their animals for longer than normal periods near the most dependable streams, ponds, and wells. These emergency concentrations may lead to overgrazing and soil disturbance in prime pastures, an example of the many ways that even low-technology economies sometimes have unintended impacts on their sustaining environment.

For several thousand years crop agriculture has been rural Africa’s most important mode of production by far. First about seven thousand years ago in the savannas of the northern part of the continent, then during the last two or three millennia in the rain forest and the savannas of the south, most African societies gradually coalesced around farming.

Agriculture spread gradually across the continent, but it did so decisively, for it gave those who adopted it a great advantage: numbers. With a dependable food supply—far more dependable than their foraging ancestors could manage—farming peoples were able to establish permanent, sometimes very large villages on lands that under foraging or herding could support only diffuse roaming bands. Agriculture took hold especially well and led to the highest population increases where soils were relatively productive, including on most of Africa’s savannas. The main crops and thus the staple foods developed by savanna farmers were grains: mainly millet, sorghum, and (after the 1500s) maize. It is logical that grains came to dominate savanna agriculture, for all the major grains were developed from graminoids, wild grasses. Grain crops thrive in grassland environments. There was a cost to the agricultural transformation of much of savanna Africa, of course: a decline in diversity as a few crop species covered more and more land that formerly had been home to multitudes of grasses and other plant types. However, nowhere is savanna Africa farmed with anything approaching the intensity of agricultural regions in North America and Europe. Africa has nothing like Illinois’s or Iowa’s vast acreages of monocropped corn. Patchworks of savanna and farmland remain the norm.

Just as grains dominate savanna agriculture, tree crops and root crops have long predominated in the rain forest zone, especially plantain, yams of many kinds, and (after the 1500s) cassava. Unlike on the savannas, rain forest agriculture generally cannot support high population densities. Soils are infertile, so the land must lie idle between cropping cycles. Typically it idles long enough for the forest to regenerate, often thirty or forty years. Under this system, large tracts of land are needed to feed small numbers of rain forest farmers because at any given time most of the land is regenerating forest, not fields. A map of Africa’s human population density at any time in the last several thousand years shows high concentrations of people in the most agriculturally productive savanna zones, as well as in some coastal areas where fishing and trade have supported development, but lower densities in the forested humid tropics (and also of course in the deserts).

Colonialism transformed African agriculture substantially during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by superimposing on local food production and trade networks an export-oriented agricultural economy that answered to the demands of Europe and the rest of the industrializing world, forcing African producers to add export crops such as cocoa, coffee, tea, peanuts, tobacco, cotton, sisal, rubber, and palm oil to the foodstuffs they had been long accustomed to producing. The next section of this chapter, about Africa in global systems, outlines some of the implications of these changes.

Figure 1.4. Cassava field in a tree savanna field, Angola.

In Africa today a smaller portion of the population is producing food because more and more rural people are moving to the cities and staying. In general, African farmers are keeping pace with the increased food demand of a growing population while also, in many areas, continuing to produce for export, though in some countries, inevitably, there are food shortfalls, especially during periods of drought or political unrest. While urban Africans depend to a considerable degree on the agricultural labors of their counterparts in the villages, they also partake in a globalized food economy and global regimes of taste, just as residents of Europe, Asia, and the Americas do. They eagerly consume not only the products of African agriculture but also imported staples and delicacies. Supermarkets and even outdoor markets in Africa’s great cities feature quantities of foods produced in their hinterlands, but also rice from China, pasta from Italy, condiments from France, and sweets from England. This is to say that Africans are no different from consumers anywhere else in their eagerness to sample diverse foods and enjoy the taste and prestige of products imported from other lands.

Yet all over the world, including Africa, it is most economical and ecologically sound to obtain the largest proportion of food from local sources, and thus urban food cultures in Africa strongly reflect the productive capacities of the different African regions. Nearly everywhere in Africa people are fond of porridges made from local starchy staple crops. Residents of East African cities such as Nairobi and Dar es Salaam and southern African cities such as Johannesburg, Harare, and Lusaka still enjoy as a primary food, respectively, ugali and mielie-meal, porridges made from the maize that farmers in these regions prefer to grow. The fufu much prized in the cities of southern Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana comes from locally produced and milled cassava and yams; the tuwo of northern Nigeria and Niger from millet or sorghum; the matoke of Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and eastern Congo from local bananas and plantains.

Over the last several centuries humankind has remade the world as we have grown dramatically in number and come to dominate the planet. The twentieth- and twenty-first-century transformation of landscape in Africa has been substantial, not only because the number of Africans has increased but also because extractive and manufacturing economies have arisen alongside agriculture to meet external demand and to support the complex and enriched lives that people worldwide—Africans are no exception—now expect. The look of Africa remains essentially African, of course, but as mines, factories, cities, roads, and all the accoutrements of the contemporary global system have arrived in Africa, the look and feel of some African places have come to resemble those of cities and industrialized landscapes everywhere. Meanwhile, despite the beginnings of an industrial transformation, many Africans have found it hard to achieve the material comfort that people everywhere seek for themselves and their children. They find it difficult largely because most of the continent entered the industrial and postindustrial age from a position of extreme disadvantage during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries under European colonialism and in its aftermath.

Colonialism arguably brought certain foundations for economic growth to Africa—ports, roadways, schools, clinics, and the like—but it did so not with the viability of an independent Africa in mind but rather to support forms of organized resource extraction that often amounted to outright plunder. New crops introduced or promoted in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because of demand in Europe drove African farmers to try to farm more intensively and to cultivate more and more land, some of it marginal and risky for agriculture. But rapid intensification and expansion led to soil fertility decline because the fertilizers necessary for sustained intensification were unavailable and fallowing land—letting it regenerate by leaving it idle for a while—became an impossible luxury, as farmers needed all available land every year.

New export crops had the potential to generate wealth in rural Africa, and wealth allows people to afford environmental conservation measures and smart rather than willy-nilly resource exploitation. However, when an agricultural transformation is organized so that the lion’s share of its proceeds flows immediately out of the producing region (in the African case, to Europe) and is unavailable for locals to invest in the betterment of their own land and society, a dynamic of decline sets in. Not only Africa’s people but also Africa’s resource base and natural beauty have suffered the depredations of a colonially transformed rural economy set up in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to drain the countryside of its natural endowment—forest products, diamonds, copper, gold, ivory, skins, cotton, cocoa, oils, coffee, tea, tobacco, peanuts, vegetables, flowers—while leaving producers and the local region with just enough to keep them producing for another year.

Colonial governments largely took rural people for granted as producers of exportable primary products, neglecting rural development except for token or inadequate efforts here and there. Perversely, Africa’s independent, postcolonial governments mostly did the same (though this has begun to change). Neglect of rural development is one reason—though hardly the only one—that Africans now are streaming to the cities.

Cities in Africa long predate colonialism, but the continent’s great metropolises—Cairo, Lagos, Kinshasa, Johannesburg, Khartoum, Abidjan, Accra, Nairobi, Kano, and others (see map 1.7)—became vast during the twentieth century and are experiencing explosive growth during the twenty-first. From all corners of rural Africa people are converging on cosmopolitan but often desperately poor cities, cauldrons of exciting cultural change and personal transformation where visions of a new Africa and new ways of being African are emerging but where lack of jobs, space, water, opportunity, health, and wealth threaten constantly to bring the whole enterprise down. Into the mining districts of South Africa, into the oil fields of Nigeria and other countries, and into the slums of great cities all over the continent pour greater and greater numbers of men, women, and children, seeking the betterment that all people want for themselves and their families; while they find vibrancy, excitement, change, and opportunity, they also encounter a more frenzied form of the poverty that they had hoped to leave behind in the countryside.

As cities and the medium-density periurban hinterlands that surround them claim more and more of Africa’s people, they are becoming the Africa that matters most to Africans. Therefore they should matter most to outsiders who are serious about Africa. That these areas be safely habitable and that they be zones of opportunity and wealth creation, not despair, is Africa’s great twenty-first-century challenge. The benefits of vibrant cities can ripple out across the land. If Africans can transform their cities into zones of opportunity, the cities will generate wealth, which can be invested—by Africans—to preserve nature and encourage sustainable production in the rural areas that fewer Africans are electing to call home.

Africa’s cities tie the fifty-four countries of the continent more and more to global systems, flows, tastes, and preferences. Globalization is no threat to Africa; it is Africa’s hope. Linkages—connections—are the world’s future, and Africans know this and will not be left behind. Connectivity, networking, and community are core African values, glorious ones, deeply rooted in the psyches and societies of nearly all African people. As success in the world increasingly depends on communications, links, networks, and community, Africans calculate that despite the adversity that the continent so obviously faces, their time in an age of global commonweal is somehow coming.

All images are courtesy of University of Wisconsin–Madison, African Studies Program.

All maps are courtesy of University of Wisconsin Cartography Lab.

Goudie, Andrew. 2006. The Human Impact on the Natural Environment: Past, Present, and Future. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

McCann, James. 1999. Green Land, Brown Land, Black Land: An Environmental History of Africa, 1800–1990. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Nederveen Pieterse, Jan. 1992. White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Stock, Robert. 2004. Africa South of the Sahara: A Geographical Interpretation. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Vansina, Jan. 1990. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.