2 |

Legacies of the Past |

Themes in African History |

Africa and its peoples have a long and distinguished history. The earliest evidence for humankind is found on the continent, and some of the first successful efforts to domesticate plants and produce metals involved African pioneers and innovators. Africans constructed complex societies, some with elaborate political hierarchies and others with dynamic governance systems without titular authorities such as kings and queens. Extensive commercial networks connected local producers in diverse environmental niches with regional markets, and these networks in turn were connected to transcontinental trade networks funneling goods to Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The trans-Atlantic slave trade did not bring European colonization to Africa; only centuries later, when Europeans had more powerful weapons and mechanized transportation, could they invade the continent. Colonial rule ended quickly, however, leaving the current configuration of more than fifty independent states.

Historians have debated whether the European colonial period was a transformative era or merely an interlude in the continent’s history. Colonial rule introduced new and enduring political boundaries and unleashed powerful economic forces that remain influential to this day, but it also was uneven in its impact and ambiguous in its transformations. Africans appropriated new ideas, but they continued to draw from the deep wells of local cultural resources. Colonial rule never was so draconian that it prevented Africans from trying to shape their own history, but African efforts were constrained. Formal educational opportunities brought new languages and topics to African students, but indigenous knowledge and the social apprenticeships associated with its transmission remained vital.

Some arguing for colonialism’s transformative power would go so far as to suggest that Africa’s history only began with the arrival of Europeans. In the early 1960s the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper noted that “perhaps in future there will be some [African] history to teach. But, at present, there is none. There is only the history of Europeans in Africa. The rest is darkness . . . and darkness is not a subject of history.”1 Trevor-Roper’s views are based on assumptions about limited African capacity that unfortunately had dominated European understandings for several generations. His scholarly discipline was only just beginning to recognize African history as a field of inquiry, even though Africans, African Americans, and others had been writing histories of the continent for centuries. It took African independence for the field of African history to flower fully as a recognized scholarly activity in Europe and North America, and in the half century since independence, historians of Africa have produced significant work and made the field a vital arena of inquiry.

This chapter cannot review all aspects of Africa’s history, nor can it convey all the developments of the last hundred years. It discusses several themes, suggesting along the way why some argue that the colonial era was an interlude and why others view it as transformative. It begins with themes related to Africa’s history before European colonial rule and then examines the European colonial conquest and its aftermath. Some themes are elaborated for the contemporary era in other chapters, and this chapter provides historical background for the more focused discussions to come. Each region has its own distinctive history, and inquisitive students will want to learn more about the African past on their own.

Africans have always been on the move. Out-migration from Africa is the most probable explanation for the peopling of the world, and migration also occurred internally. The earliest movements are impossible to reconstruct, but Africa’s linguistic diversity provides a key to uncovering some of this past. Africans currently speak more than two thousand distinct languages, but each language falls into one of four large language families that initially developed separately for millennia: Afro-Asiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Saharan. Languages in the same family share some vocabulary and certain grammatical features, and each language develops on its own terms, often as a dialect of an existing language before transformations create a new language. Archeological and botanical analyses suggest that the initial linguistic diversity reflects different choices about the transition from gathering and hunting to food production: speakers of the Khoisan languages retained the earliest human lifestyle in the Kalahari Desert and isolated regions in eastern Africa, whereas populations associated with the other language families shifted to food production with different main crops at various times beginning several thousand years ago. These transitions were complex, and subsequent historical events encouraged further cultural transformations, so the current distribution of languages reflects the outcome of thousands of years of interactions. Africans identify as speakers of specific languages associated with recent ancestors: the origins of Africa’s cultural diversity are well beyond human memory and reflected obliquely in its four distinct language families.

Settling the continent was not easy. Europeans in the Age of Exploration imagined Africa as a tropical paradise where its inhabitants lived easily off the land. But the continent actually has poor soils except in a few favored contexts, unpredictable rainfall in regions outside the rain forest, and debilitating diseases that afflict humans and domesticated animals alike. Each region had both obstacles and opportunities for the establishment of food-producing regimes. In eastern Africa, for example, the highlands dotting the arid plains west of the coast offered environments where farming was possible, creating islands of demographic concentration in a region where otherwise herding was more viable. Everywhere the production of metals was essential to the full exploitation of any region, and ironworkers emerged as specialists who awed others with their ability to transform ore into workable metal for tools and weapons. In all contexts there was an emphasis on fertility in the face of ubiquitous diseases and other hardships, and Africans transmitted local knowledge about healing and other activities over the generations. The chapters on health, visual art, and other African cultural expressions reveal contemporary elaborations of these practices.

Cultural interaction and incorporation frequently occurred. The widespread distribution of Bantu-speakers in central, eastern, and southern Africa, for example, involved diverse processes over the millennia. European colonial officials initially spoke of a “Bantu conquest,” projecting their own imperial expansion onto others in the past. Later scholars imagined a “Bantu migration” bringing knowledge of ironworking from an initial home in western Africa to sub-equatorial Africa. The archeological evidence for a phased spread of ironworking well over a thousand years ago made the second explanation plausible, but careful analysis uncovers complexities. Instead of Iron Age farmers migrating into unoccupied regions, historians now posit a range of scenarios depending upon the linguistic, archeological, and other evidence: ideas could move without people, for example, or the migrations might only involve small groups of ironworkers. Some of these processes are evident in subsequent historical eras. For instance, in regions of central Africa where western Bantu languages are spoken, patron-client relations involving individuals capable of bringing people under their protection is a dominant pattern of the last several hundred years. These leaders, some still remembered by those whose ancestors were incorporated into their entourages, drew clients through their distribution of material largesse, perceived powers to both protect and heal, and knowledge of the physical environment. In southern Africa, where another branch of the Bantu languages is dominant, a cattle-keeping cultural complex facilitated social incorporation during the past several hundred years: bonds were forged not only in the keeping of cattle and the arrangement of marriages around them, but also through age-grade organizations incorporating young men and women through initiatory rituals. Such processes of incorporation through patron-client relations, age-grade initiations, and other social processes, as well as the literal migrations of peoples, explain the current distribution of Bantu and other languages in Africa.

Interactions occurred across numerous frontiers over the centuries. The Hollywood image of the American frontier as the product of a linear westward expansion over a short period from settlements in the eastern United States is not especially relevant in the African context, for the African experience occurred over millennia with multiple cultural centers and several frontiers moving in various directions. In eastern Africa, for example, the expansion of the Bantu languages occurred where the Nilo-Saharan languages also were expanding, and both converged in a context where Khoisan and Cushitic languages (the latter a branch of the Afro-Asiatic family) were already established. Analysis of material cultures, word lists, and oral narrations allows historians to reconstruct histories for individual groups. In the Great Lakes region, which is suitable for agriculture, pastoralism, and foraging, cultural interactions over several hundred years between speakers of several different languages created regional social formations in which farmers, herders, and gatherers came to speak the same language. Sometimes groups moved into environmental niches unexploited by others: the Swahili peoples, speakers of a Bantu language, for example, separated from other eastern Bantu-speakers and moved into the coastal regions of East Africa as fisherfolk and farmers more than a thousand years ago and then engaged in international trade. Other population movements are closer in time: the Maasai peoples, speakers of a Nilo-Saharan language, have a long history as a people but came to exercise dominance in the Rift Valley of today’s Kenya and Tanzania only in the nineteenth century, as they followed the guidance of religious leaders, expanded into the valley, accumulated cattle, and incorporated others in complex social and commercial relations. The metaphor of the frontier is useful, as it reminds us that African cultures were not isolated into fixed social groupings but were open and dynamic, even if they came into conflict over resources during times of scarcity.

Mobility sometimes led to the founding of towns. Ancient Egypt produced the first African urban centers along the banks of the lower Nile River. Regional trade encouraged the rise of market towns, which later became connected to longdistance exchanges across the Sahara Desert, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean. Timbuktu, the famed West African urban center on the edge of the Sahara, was one of thousands of such commercial towns in African history. Other towns were founded by political elites seeking to project their power spatially and to draw subjects to their courts. These towns impressed the initial European visitors to coastal Africa in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Towns declined when historical circumstances changed. The archeological site known as Igbo-Ukwu in today’s southeastern Nigeria, for example, points to the existence over a millennium ago of a political capital where, at the time of its excavation, only villages dotted the same countryside. Europeans sometimes founded new towns in the colonial era, but they also expanded existing towns: in northern Nigeria, Kano pushed beyond its old city walls, and Italians built monumental architecture in the old town of Mogadishu in Somalia. The postcolonial era has been a time of dramatic urbanization. Rural-urban migration and other forms of mobility such as African immigration to Abu Dhabi and Guangzhou, London and Paris, and Minneapolis and New York are recent examples of a long-standing practice of African exploration of new horizons.

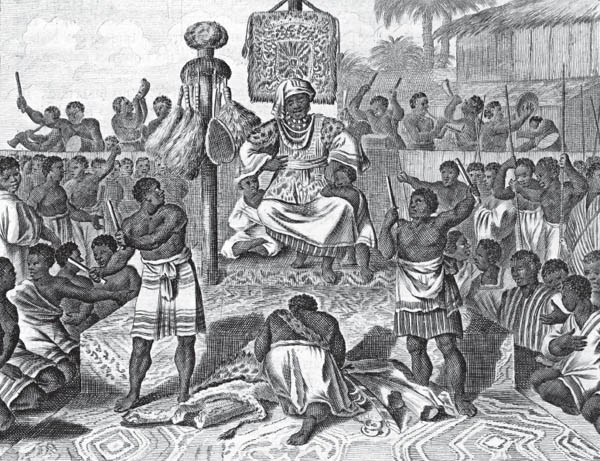

Figure 2.1. Court life in the central African town of Loango, as represented in a seventeenth-century European drawing in O. Drapper, Description de l’afrique, 1686.

Lilly Library, Indiana University.

The United Nations is an international body composed of states, the primary political units of the contemporary world. States also have been used as a marker of human development, as centralized authorities often built monuments and left behind written documents valued by archeologists and historians. However, social complexity and cultural sophistication occur just as often in decentralized formations, even if their members do not build enduring structures or if they prefer oral modes of communication. Anthropologists have revealed how societies govern themselves effectively through elders representing corporate groups, and some archeologists and historians have pursued new methodological angles to uncover the history of decentralized societies, as the previous discussion of migration and cultural exchanges discloses. In this section the focus turns to instances of increasingly centralized African social forms. Precolonial African history long has been the story of African states, and this section does not attempt to summarize that past. Instead, examples are chosen from three regions: the lower Nile River valley, the central plateau of Zimbabwe, and the middle Niger River valley. Just a few decades ago these three examples were contested, denied, or unknown, respectively, so their examination here underscores the importance of recognizing African social complexity in the face of erasure and neglect by previous generations of scholars.

The inclusion of ancient Egypt as an African example would have given Hugh Trevor-Roper and numerous others pause. Many divide the history of the African continent at the Sahara, but the history of population movements and the cross-fertilization of ideas belie such facile divisions. The Sahara emerged as the world’s largest desert only several thousand years ago, and thereafter it has been regularly traversed by Africans and others carrying new technologies, ideas, faiths, and trade goods. Just six thousand years ago, the Sahara had a large inland sea, and settlements along its shores included those who fished the waters, hunted the nearby fauna, and experimented with the domestication of animals and plants. Surviving Saharan rock paintings illustrate these activities, and recent archeological findings point to the social complexity of the human populations living there. Ecological change as well as global climatic developments contributed to growing aridity in the Sahara, forcing most of the Sahara’s populations to migrate to more favorable circumstances elsewhere on the continent. The lower Nile River valley was one of several destinations. The migrants joined other Africans who continued their experimentation with domesticated crops, given new relevance by increasing populations.

Well before the rise of pyramids and other monumental buildings in the lower Nile valley, Africans learned how to manage the annual silting patterns of the Nile River. These populations were the first in Africa to adopt agriculture on a widespread scale. Eventually African elites from settlements in Upper Egypt imposed a centralized state over populations throughout the lower reaches of the Nile valley, sustaining three centuries of pharaonic rule in ancient Egypt. The emergence of centralized rule also occurred upriver in Nubia among groups speaking a different language, revealing that it was not pharaonic exceptionalism but the ability and need to centralize that created the first African states; later the Nubians conquered and ruled ancient Egypt for a brief period. The succession of ancient Egyptian dynasties associated with the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms oversaw developments in law and governance, health and medicine, the arts, and architecture. Ancient Egypt was a major power, projecting influence upon its neighbors and receiving cultural influences from throughout the region. In religious affairs, ancient Egyptians stressed their indebtedness to the black earth inundating the Nile’s banks from its origins in the African interior, and their temple doors opened to the lands of their ancestors, the regions lying toward the headwaters of the Nile.

The place of ancient Egypt in African history has been contested during the recent past. After Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt, Egyptology emerged as a distinct scholarly enterprise removed from other historical fields. African and African American scholars questioned this separation: the West African historian Cheikh Anta Diop, for example, wrote several influential books about the African origins of ancient Egypt, and similar views were expressed in African American intellectual circles beginning in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and continuing in more recent works by African American scholars. The latter pushed for a new academic agenda, Afrocentrism, which protested the erasure of ancient Egypt from the dominant representations of Africa and framed African history in its own analytical categories, beginning with ancient Egypt as the first African civilization. This effort drove other debates in American intellectual life, including the argument over whether public schools should embrace multiculturalism; in some important respects, today’s school standards are a result of the debate Afrocentrists initiated about the place of ancient Egypt in African history. Some of their conclusions about the past may be contested, but not their essential point: that ancient Egypt was African in origin and represented broader patterns of African history.

After the emergence of the Sahara Desert and the rise and decline of lower Nile valley social formations, northern Africa followed its own regional trajectory. It was the southern shore of an interrelated Mediterranean world, as Ferdinand Braudel imagined in his influential historical works. The rise of Islam also brought the Arab conquest of northern Africa in the seventh century CE, leading to the complex social transformations associated with the adoption of Arabic and the acceptance of Islam as the dominant religion in the region. But Islam equally linked all Muslims to common sacred texts and ritual practices, so northern Africa never was isolated from other African regions, where Islam also expanded gradually as one religion among many. Trade across the Sahara was another factor integrating the region Muslims called the Bilad as-Sudan, “land of the blacks,” into complex commercial and diplomatic relations with northern Africa. Much later Arabs also began to migrate to selected sub-Saharan contexts, such as oases in the western Sahara (today’s Mauritania) and the middle Nile River valley (today’s northern Sudan), stimulating again the process of local adoption of the Arabic language. But Arabization in sub-Saharan Africa did not mean that Nubians forgot the past associated with their ancestors, who with the ancient Egyptians produced impressive societies along the banks of the Nile River. And Gamal Abdul Nasser, Egypt’s leader during the 1950s and 1960s, celebrated his country’s African heritage as well as its Arab and Muslim cultural ties.

One of southern Africa’s states left behind massive stone buildings near the Zimbabwean town of Masvingo. Great Zimbabwe, as this complex has come to be known, was the residence of some twenty thousand inhabitants at its apogee in the fourteenth century. Located on a plateau, the complex as well as other structures likely housed elites and laborers responsible for the buildings, which are made of almost a million large granite blocks. Goldworking was a central part of this state’s modus vivendi, accomplished by using iron smelting and smithing to extract gold ore from its rocky prison beginning around 1000 CE. Gold was also exported to the coasts via the Swahili trading town of Sofala; ivory and enslaved people were exchanged as well. By the fourteenth century, Great Zimbabwe was fully integrated into the Indian Ocean commercial world (see below), with elites displaying imported Chinese porcelain and local bird sculptures made from soapstone found in the region. In addition, smaller stone structures were built throughout the plateau. By the 1500s, however, Great Zimbabwe’s population had migrated: some postulate a massive fire, and others suggest that overpopulation depleted the natural environment around the settlement on the plateau. Whatever the case, the inhabitants of Great Zimbabwe took their prospecting and goldworking technologies with them elsewhere in the region, including the Mutapa state near the Zambezi River. As the Portuguese rounded southern Africa and intervened in the region during the sixteenth century, they traded with the Mutapa state, but it eventually was eclipsed on the plateau by the Torwa and Changamire polities.

Figure 2.2. Great Zimbabwe’s conical tower, a photograph taken by the colonial expedition seeking evidence for non-African origins of the granite structures and discussed in R. N. Hall, Great Zimbabwe, Mashonaland, Rhodesia: An Account of Two Years Examination Work in 1902–04 on Behalf of the Government of Rhodesia, 1907.

Lilly Library, Indiana University.

When Europeans first arrived in southern Africa as colonial rulers, they assumed that Africans could not have built or even been associated with Great Zimbabwe. In Rhodesia, the territory named after the British entrepreneur Cecil Rhodes, the colonial government’s museum authority actively propagated the myth that non-African, white peoples had built Great Zimbabwe, even though evidence produced by professional archeologists and historians pointed to African origins. Leaving behind physical evidence of a major social formation did not prevent the erasure of African involvement in the era of European domination and racism. This denial of ancient African stone-building was reversed only when African nationalists came to power in the 1980s and renamed the nation Zimbabwe after this heritage.

The middle Niger River valley was the site of a western African culture that has come into clearer view only recently, with the discovery of new archeological evidence. This culture is not associated with monumental buildings, as are the social formations in the lower Nile valley and on the Zimbabwean plateau. It is tied to social transformations in the fertile inland delta of the Niger River, situated in the heart of contemporary Mali. There, in the years after the desertification of the Sahara, Africans domesticated local grains and developed regional trade across the close succession of environmental zones running north and south from the Sahara Desert to the rain forest. As trade expanded, occupational specialization and urbanization increased. These regional developments are evident in the rise of Jenne-jeno, or “Old Jenne,” which had emerged as a thriving town by 400 BCE and expanded until it reached some ten thousand residents during the first millennium CE. Today the archeological site is on an island close to Jenne, the contemporary commercial town and Muslim religious center.

At its genesis and for much of its history, the middle Niger River valley social formation did not reflect the centralization of political authority, witnessed, for instance, by the absence of monumental architecture and elaborate royal burial tombs as in ancient Egypt; instead the local inhabitants embraced social diversity and ethnic accommodation. Today, reciprocal relations among Mali’s ethnic groups specializing in farming, herding, and fishing in the middle Niger River valley harken back to enduring values of cultural diversity forged thousands of years ago.

Centralized political formations did eventually develop. Gold had been discovered in the early days of Jenne-jeno and was traded regionally, and the expansion of trans-Saharan trade created incentives for political elites to control access to this luxury commodity. Soninke-speaking political elites founded Wagadu (the state referred to as “Ghana” in Arabic texts by Muslim travelers), the first West African empire to benefit from control of the trans-Saharan gold trade. Ancient Mali rose to prominence in the early thirteenth century and oversaw regional integration over a wide swath of West Africa for three hundred years, transforming control over the gold trade into a mechanism for projecting its political and cultural power regionally. Today the Mande languages are spoken throughout the region, a legacy of ancient Mali, much as the Romance languages of western Europe are a legacy of the ancient Roman Empire. Ancient Mali’s origins are celebrated in the orally transmitted Sunjata epic, which is recounted to this day. Sunjata Keita, the “Lion King,” reportedly was unable to walk until well past puberty, but rose in a feat of great strength through the assistance of a blacksmith and praise singer. Later in this oral epic, Sunjata battled Sumanguru Kante, a blacksmith, sorcerer, and king. Whatever the meanings of this epic, it codified the social relations forged by the Keita dynasty and other Malian elites. This social system was enduring: even after the fall of ancient Mali as a political formation, its social structure defined group relations until the present in three categories: horon (nobles, farmers, and merchants), nyamakalaw (artisan groups such as ironworkers, potters, leatherworkers, and bards), and jonw (outsiders or “slaves”). While nobles claimed pride of place, artisans stressed that nobles depended upon their services. Slaves were not always bound to a life of menial labor, and some rose to positions of great authority as soldiers. The nonhierarchical ethos of the Jenne-jeno era echoed in these contestations among social groups.

As in the cases of ancient Egypt and Great Zimbabwe, ancient Mali declined as an empire. In the shifting political context and changing commercial relations of fifteenth-century West Africa, the Songhay state took control of much of the trans-Saharan gold trade. The political elites of ancient Mali survived, albeit in a smaller political formation, and members of the Keita family still commanded local respect. The Songhay became an empire but eventually declined as well, in its case due to a combination of factors, including the diversion of the gold trade to coastal forts trading with European merchants in the sixteenth century. This latter development points to other commercial networks shaping African history besides trans-Saharan trade.

Globalization refers to the widespread economic integration and increasing cultural and technological flows in today’s interconnected world. But economic connections and cultural interactions across vast regions are not unknown in human history. Trans-Saharan trade linked sub-Saharan Africa to Mediterranean and Asian trading networks, and cultural flows such as the Islamic religion circulated along these networks. Other trade networks connected Africa to South Asia and the Americas across the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, respectively.

The Indian Ocean was the locus of one of the world’s first global economies, a trading system linking eastern Africa with Arabia, southern Asia, and Indonesia. The regularity of the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean facilitated economic integration: the dependable shift between northeasterly and southwesterly winds over the course of the year allowed premodern seafaring vessels to move goods, ideas, technologies, and peoples between the continents. An interconnected zone emerged, most markedly from the tenth to nineteenth centuries, when economic linkages supported a wider array of cultural exchanges. No one power dominated the Indian Ocean world of that era, although Islam was the faith of many of the merchants who moved goods and ideas across the seas. When the first Portuguese ships rounded South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and arrived in the Indian Ocean world in the sixteenth century, they found a thriving economy that they tried to control, but their gunboats only allowed them to seize a few ports, such as Mombasa, and did not alter the fundamental patterns immediately. It was only the rise of an industrializing global economy centered on western Europe that eroded the economic and cultural integration of the Indian Ocean world during the last few centuries.

Figure 2.3. Mombasa, with the castle built by the Portuguese in the late sixteenth century, as represented in a nineteenth-century European drawing in W. F. W. Owen, Narrative of Voyages to Explore the Shores of Africa, Arabia and Madagascar, 1833.

Lilly Library, Indiana University.

Coastal eastern Africa was one of several African regions integrated into the larger Indian Ocean world. The Horn of Africa and northern regions of coastal eastern Africa long had been linked to the Red Sea and Mediterranean exchanges: one of the documents describing the earlier commercial system, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, from the first century CE, mentions eastern African involvement with global markets and international merchants from the Mediterranean and western Asia. The expansion of Islam further integrated global trade beginning in the eighth century CE. This trade had its extensions into the broader Indian Ocean world, as dramatically demonstrated by the early fifteenth-century expedition of Zheng He, a Chinese admiral who made a trip to eastern Africa and returned with a live giraffe as a gift for the Ming emperor. The more common exchanges involved African resources, such as gold, ivory, aromatic substances, and timber, for Asian textiles, ceramics, and luxury goods. Seafaring vessels known as dhows, wooden ships with lateen sails, moved between eastern Africa, Arabia, and India, as the monsoon winds allowed travel between these points easily in one trading season.

Africans involved in these Indian Ocean exchanges include the Swahili peoples. They occupied the ecological niche of mangrove coastal forests and coral reefs, which abutted arid desert in the northern regions of eastern Africa and provided the basis for thriving commercial towns along the coast from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique. They spoke a Bantu language, to which were added words from other African languages as well as from Arabic. The Swahili peoples began converting to Islam beginning in the ninth century, and Islam eventually came to be associated intimately with Swahili culture. Exchanges with Muslims across the Indian Ocean occurred, with Arab scholars from neighboring Oman and Yemen frequently visiting the Swahili coast and sometimes settling there, with their descendants becoming Swahili themselves over the generations. Swahili families maintain traditions of origins from elsewhere as well, with some claiming Shungwaya origins, rumored to be in the East African hinterland, and others asserting more distant connections to Shiraz, a Persian trading port. Whatever the historicity of these claims, the social formation along the eastern African coast was African in its origins even as it constructed a cosmopolitan identity.

Various polities emerged to control the trade along the eastern African coast. The Swahili peoples constructed city-states, and they competed with one another for influence in overseas trade; local histories recount these rivalries and the rise and fall of local dynasties. The northern city-states had the initial advantages because of their closer proximity to Asian trading partners, but Kilwa, on Tanzania’s central coast, emerged as the most powerful city-state of the fourteenth century as a result of its involvement in the gold trade associated with Great Zimbabwe. The Portuguese used their ship-based cannon to seize control of coastal trade, especially the lucrative export of gold in the sixteenth century. With the decline of Portuguese influence, the Swahili city-states fell under the domination of another regional power, Oman, which used divide-and-conquer strategies to win over some city-states, defeat others, and construct a commercial empire based on the island of Zanzibar, which for centuries was a center of clove production. During the Omani era, clove production dramatically expanded and trade with the interior increased significantly, as the former pattern of waiting for interior merchants coming to the coast was replaced with caravans embarking from the coast. These caravans were armed, and their traders disrupted the lives of humans and animals alike in their search for ivory and slaves to transport to the coast. The ivory went to support the demand for billiard balls, gun handles, and letter openers for the middle classes of Europe, and the slaves often remained behind to work on clove plantations owned by Omani and Swahili elites. Some slaves worked as porters, and with less-wealthy Swahili merchants they strove to extricate themselves from an elaborate system of credit bankrolled by Omani political elites, South Asian financiers, and wealthier Swahili merchants. It was a dynamic era of social transformation, with interior cultures influencing the coast as much as Omani culture did. This cultural dynamism, however, could not prevent the region’s subordination to European economic powers, which first traded along the coast and then used treaty relations to assert colonial control in the late nineteenth century.

The Atlantic world emerged as a commercial system centuries after the rise of the Indian Ocean system. It emerged in the aftermath of European voyages of exploration linking Europe with western Africa and the Americas. In contrast to the Indian Ocean world, the Atlantic world was not based on environmental forces such as monsoon winds that facilitated exchanges. In fact, the Atlantic’s ocean currents and prevailing winds long limited contact between Europe and both the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa. Once Iberians adapted lateen sails and other technological advances to their sturdy oceangoing vessels, regular contact between the continents was possible, and soon other western European powers followed the Portuguese and Spanish in sailing the shores of the Atlantic. These activities facilitated a series of exchanges across the Atlantic world. One was the movement of plants, animals, and diseases. Crops from the Americas, such as corn and squash, soon were cultivated in Europe and Africa, and European and African foodstuffs and animals were imported to the Americas. Diseases also crossed the ocean, and in the Americas and southern Africa the arrival of European diseases unfortunately led to deaths among Amerindian and African populations without natural immunities. Another dimension of the Atlantic world was the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Western Europeans, who had colonized the Americas and the southernmost point of Africa, organized the largest forced migration in world history through the importation of Africans to the Americas as slave labor. The plantation systems created in the Americas were novel social institutions: in addition to innovations in capitalism underlying their formation, the plantations relied on the knowledge of tropical farming that Africans carried to the Americas. The African contributions to the emerging Atlantic world were innumerable but only recently have historians appreciated their role.

Scholars have debated many aspects of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. One issue concerns African participation in the processes of enslavement, slave trading, and slave holding. Before direct contact with Europeans, West Africans most certainly practiced slavery, but they integrated slaves into social formations with different operating principles and certainly not on the scale that would occur on plantations in the Americas. African war captives found themselves serving political elites, and sometimes rising to positions of influence; indebtedness could see a person volunteer for or be forced into domestic or agricultural service until such time as those financial obligations had been paid off; and Africans convicted of crimes might be punished with servitude to individuals or corporate groups. Slaves were integrated into African communities as domestic servants, farmhands working alongside their patrons, assistants to artisans, petty traders in commercial firms, and professional soldiers and even governors for political elites. In African contexts, over time slaves usually gained more and more rights and privileges; for example, children of enslaved individuals usually took the names of their parents, could not be sold to others, and were entitled to inheritance shares. The gendered nature of servitude also differed in western Atlantic and African contexts, as African men were sold disproportionately into trans-Atlantic networks. Slave trading also was practiced, with slaves sold both internally and across the Indian Ocean and the Sahara Desert for thousands of years. Even though the trans-Atlantic slave trade built on these foundations, it established other precedents and took millions of Africans to plantation servitude within a span of only several hundred years. The social processes unleashed by the trans-Atlantic trade altered the African continent in significant ways.

The plantation system in the Americas was a particularly rigorous labor regime. It emerged out of a historical context, with origins in the Levant, elaboration in the Mediterranean, and exportation and further elaboration in the Americas, where it was tied to emerging forms of capitalism. In North and South America it organized mass labor for the most efficient production of crops such as sugar, which fetched high prices in the expanding Atlantic economy. By the end of the sixteenth century, demand for sugar propelled the slave mode of production throughout the entire western tropical Atlantic basin, especially in the Caribbean and Brazil. Sugar could be sold as it was or made into hard spirits such as rum, the production of which relied on additional slave labor. The emergence of privateers and pirates is a lasting legacy to the ascendancy of the sugar and alcohol economies of the Caribbean. Exported sugar and rum went to Europe and Africa to be traded for other goods. In Africa, however, the voracious demand for enslaved Africans—high mortality rates meant that plantations required a constant resupply of slave labor—drove the commercial exchanges. African elites served as willing providers as they pursued financial and technological opportunities to unseat old and new rivals. Careful study of slave shippers’ cargo logs led historians to the figure of approximately twelve million African arrivals in the Americas during the era of the plantation economy; unknown are the numbers of Africans who died during the Middle Passage or in slave raids in Africa.

As demand for slaves to work in the Americas rose, African societies were transformed. Among African slave traders, the previous system of exchanging persons eroded and captives were treated as commodities. African traders sometimes organized raiding parties to obtain persons for exchange with Europeans, in return receiving weaponry, glass beads, metal, and other goods. Warfare increased over time as well, as African political elites found a market for war captives. Regulatory spiritual systems intended to mete out justice in local contexts were contorted by this demand: condemned persons now could be sold to Europeans. Given the preference for men in the external trade, female captives often remained in Africa as dependents of political elites and merchants. Oral traditions, at least the ones controlled by male agency, changed to reflect these transformations, projecting back into the past narratives of male dominance in many societies where women’s historical roles had been far greater.

Overall, the level of social subordination increased as larger numbers of disenfranchised people became dependent upon others for safety. Ultimately the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade allowed some Africans to grow wealthy, primarily coastal traders and African political authorities who fought wars in the interior and sold captives at the coast. Not all societies experienced the same repercussions: some were not very involved, while others lost substantial numbers of adult men and women with considerable expertise and knowledge. Some, such as stretches of coast spanning present-day Liberia and Sierra Leone, received influxes of formerly enslaved people liberated by British naval efforts, creating new, creolized societies rich with tensions sparked by the arrival of these outsiders. Abolitionist efforts in the nineteenth century led to further transformations, as Europeans, including the British, reversed course and no longer purchased slaves, introducing the era of “legitimate commerce” in the nineteenth century. The historical forces leading to wars and enslavement in Africa were not halted, and captives entered regional slave markets and remained in Africa, producing cash crops for sale as “legitimate” goods in global markets. Africa now exported not slaves but peanuts and palm kernels, the extracted oils of which lubricated machines in the factories of the early Industrial Revolution.

During the trans-Atlantic slave trade Europeans negotiated with African elites for the right to build and reside in forts and other coastal enclaves. For years Europeans remained content to stay on the coast and engage in commerce with Africans who traveled to them. During the course of the nineteenth century, however, Europeans began to project their power into the interior. This was the era of travelers and explorers who, among other things, sought to “discover” the sources of the Nile and Niger Rivers; their publications in geographical journals supported those interested in expanding “legitimate commerce” and also sparked new interest by European powers. Commerce remained an activity that brought benefits to all parties, and Europeans made contacts with a plethora of local authorities further and further in the interior, offering treaties of trade and protection. These were but the first steps in a process that culminated in European colonial rule in Africa.

Some scholars speak of the “scramble” for Africa when describing the processes that brought European colonial control over most of the African continent in the nineteenth century. From the European perspective, it was a flurry of activity, especially during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, when the pace of intervention accelerated in sub-Saharan Africa. Seven European powers, led by Britain, France, and Germany and including Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the Belgian monarch Leopold II, carved up the continent. These powers engaged in diplomacy among themselves to set terms for dividing the continent into “spheres of influence” before they moved to extend effective occupation through force into those spheres. Historians of European imperialism debate the salience of economic, military, and diplomatic factors in the conquest of Africa. Those who argue for the pressing need of capitalist enterprises to invest abroad overstate their case, but the economic potential of African territories certainly drove the expansion, as did diplomatic rivalries, the desire of European military leaders to make a name for themselves, and local crises which that led some powers to intervene. What emerges from the debate is that the era might best be understood from the European perspective as a series of regional inventions, each with specific economic and political causes, made possible by changes in the technological and military capacities of European powers and the growing racism of the time, which allowed them to justify their actions as a “civilizing mission,” complete with social Darwinist and pseudo-scientific justifications.

Africans were not mere bystanders to this event. Although African political leaders were not invited to the 1884–85 Berlin conference where the “rules” of the partition were established, they engaged in efforts to negotiate with agents of European powers who offered them commercial relations and “protection.” When Europeans moved to occupy the continent, some African leaders resisted militarily, whereas others tried to obtain favorable positions in the new colonial administration. Some have sought to cast Africans as either “resisters” or “collaborators,” but these binary terms obscure the complexities of the times, when Africans adopted diverse and changing strategies to protect their interests in the face of European occupation of the continent. Some who interacted with Europeans also did so to derive benefits for their communities: a pan-African sense of a common front did not emerge, although a dense network of allegiances did arise among some African communities as European power touched more and more people and African political, economic, and social institutions. In the end, except in the case of the Ethiopian defeat of the Italians at Adwa in 1896, resistance did not prevent colonial occupation. But the era of resistance underscores African agency in the face of forceful European assertions. Clearly the term “scramble” does not capture fully this violent era of European conquest.

European colonial rule had many dimensions, and the following thematic analysis can only begin to discuss the impact of the era for Africa and its peoples. The first point to acknowledge is that the partition of Africa left a clear legacy to contemporary Africa: the current political borders of African nation-states largely adopt the ad hoc imperial geography of the “scramble.” Colonial boundaries were altered slightly after World War I as responsibility for the former German colonies in western, southern, and eastern Africa was given to the war’s victors, Britain and France, who often incorporated the territories into existing colonies. Boundaries changed again slightly after World War II: the most notable example was the integration of the former Italian colony of Eritrea into Ethiopia, which had suffered an Italian invasion in the 1930s and gained liberation with Eritrea as a new province in the 1950s. This case perhaps illustrates the durability of colonial boundaries: in the 1990s Eritrean liberation forces won the right to form an independent Eritrean state, the boundaries of which followed the former colonial borders with Ethiopia. It is not arbitrary lines across African soils that make boundaries endure, however; the political, economic, social, and other transformations that occurred within those colonial territories continue to influence the present.

Once European powers divided and conquered Africa, they had to rule over its inhabitants. Force and the threat of its use remained a major component of colonial rule for decades, as small numbers of European officials claimed authority over large territories with restive populations speaking languages they did not know. Europeans also turned to Africans to assist them in ruling the continent. Leaders who had signed treaties were one group securing subordinate roles in the colonial administrative hierarchy, but in contexts without such authorities or where leaders had resisted, Europeans recruited others, often adventurers willing to fill these roles. Historians discuss the administrative styles of the European powers, emphasizing, for example, British “indirect rule” and the maintenance of African cultures as opposed to French emphasis on the “assimilation” of French culture by a few Africans and “direct rule” imposed on the masses. Such differences are evident in some cases, but the Great Depression led most powers to reduce expenses and rule indirectly through African intermediaries. Current research is focusing on these chiefs, clerks, translators, tax collectors, and police officers, revealing how they actively shaped colonial rule: European superiors relied on their knowledge to make decisions and then turned to them to implement colonial policies. Recently some historians have argued that African chiefs recognized by the British did not preserve long-standing cultural practices but “invented” traditions to bolster their standing. While there were limits to this kind of invention, it is not surprising that African cultures remained vibrantly dynamic even in the colonial period. The larger point is that a few Africans had greater access to power and influence than others, and analyses of how these African actors turned colonial rule to their advantage in particular contexts is the key to understanding the long-term legacy of European rule in any given former colonial territory.

European officials used their resources and power to set the economic orientation of colonial Africa, although Africans still exercised agency and influenced outcomes in some cases. Colonial administrations favored expanded international trade and built coastal seaports and a network of railroads and later motor routes that facilitated the export of cash crops and mineral wealth from Africa in exchange for consumer goods from Europe. Securing labor was another issue. Forced labor was an option, which resulted in brutal practices by the concessionary companies in the first years of the Congo Free State. Even though these abuses were halted in the early twentieth century, authoritarian labor regimes remained important there and in other colonies where forced labor was employed. Another option was to impose new currencies and demand payment of taxes in cash, thereby forcing Africans to work for European firms or produce and sell cash crops. These taxation policies generated a workforce for the capital-intensive mineral extraction operations established by European firms in southern and central Africa. It also encouraged Africans to produce on their own initiative cash crops, such as cocoa, coffee, and peanuts, for sale in western Africa and selected regions of eastern, central, and southern Africa. African producers also sometimes thwarted colonial designs to establish European plantations; for example, Africans responded with alacrity to the completion of the railhead from coastal Kenya to Uganda by producing large quantities of cotton, which undercut colonial plans to have European settlers produce this crop. Even when European colonists arrived in other contexts, Africans still outproduced settler farmers, at least until colonial laws favored the Europeans, with the result that they ended up working on settler farms. This development illuminates the political economy of the colonial era: where Europeans settled in large numbers, such as the mineral-rich territories of central and southern Africa and the mosquito-free highlands of eastern Africa, settler interests trumped those of the African inhabitants of the territory. Even in western Africa, where cash crop production was in African hands and few European settlers lived, colonial policies worked to give advantages to the European firms that dominated the lucrative export sector. Many African-owned businesses folded as discriminatory practices pursued by banks, companies, goods transporters, and others increasingly made it difficult for Africans to compete effectively.

Figure 2.4. Police officer in the French colony of Côte d’Ivoire, as represented by a twentieth-century African carving. Courtesy of Indiana University Art Museum.

Collection of Rita and John Grunwald.

Colonial rule encouraged Africans to obtain formal education in European languages and to follow European curricula. One might imagine that this effort would have been central to the era, given the “civilizing mission” espoused during the European partition of Africa. But colonial administrations devoted few resources to provide education to Africans. Mass education never was a goal: they founded schools for sons of chiefs and others whom they wanted to recruit into the colonial administration, and they relied on Christian missionaries to provide education to others. Some Africans saw the value of education in European languages and seized on these opportunities. Historical research on colonial encounters reveals the complexity of the cultural transformations: educated Africans were “middle figures” with knowledge of multiple cultures who acted on their own visions of the future. They reconfigured European ideas to fit local circumstances, and they added indigenous knowledge and values to the equation. These Africans helped expand Christianity in Africa, for example, working as catechists and translating the message of the church into culturally understandable terms, as the chapter on religion discusses at greater length. Some Africans attended institutions of higher learning in Europe and the United States, and in these contexts they made connections, became aware of and elaborated upon the idea of Pan-Africanism, and developed their own ideas about political change on the continent. These and other educated Africans burst onto the political scene in the late colonial era, as they came to demand greater participation in political life and articulated African understandings of nationalism.

The decades after World War II were a time of political change for the continent. African nationalists and others pushed for and won independence. There were other changes as well. For example, European powers embarked on economic development schemes that sought to increase African production to benefit metropolitan nations devastated by the war. When finally forced to decolonize, European sought to devolve power to African elites whom they hoped would continue to value these economic ties, a relationship some derided as “neocolonialism.” Even if African political elites cut ties with the former colonial powers and embarked on new policies, they often pursued schemes to increase production and thus continued the development policies of the late colonial era.

European powers had hoped to keep their colonies for longer than they did, but forces from within and without pushed change. The new Cold War powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, put pressure on Europeans to decolonize Africa, with immediate results seen in the former Italian possessions of Eritrea, Libya, and Somalia and in northern Africa, where the French granted independence to Morocco and Tunisia. Elsewhere, internal pressure was needed. African workers made clear their displeasure with conditions in a series of uncoordinated labor actions in ports and key economic domains during the late 1940s; African soldiers who had served in European armies during the war added their voices, plus detailed knowledge of European weapons and military tactics, to the civil discontent. Pressing forward too were educated elites who organized political movements to call for self-government. African lawyers and other professionals long had petitioned colonial governments for local involvement in political affairs, but the postwar era brought a new generation of more aggressive leaders, who constructed mass-based movements to apply pressure on colonial powers.

The decolonization process followed its own logic in each territory, but general patterns emerged. Europeans moved to devolve power more quickly in western Africa, where European settler interests did not complicate the transition. There the British and French pursued different strategies and handed over power in the 1950s and early 1960s. The French allowed a gradually widening franchise to vote for representatives to the metropolitan legislative body, and these African representatives pushed for greater changes, such as the elimination of forced labor and ultimately the devolution of power to locally elected leaders. The British also increased the franchise, but for elections to existing legislative councils in the colonies, long with only token African members, to transition initially to African control of internal affairs and eventually full independence. These patterns were evident in eastern Africa too in areas where settlers were not a dominant force, as in Tanganyika and Uganda, which gained independence in the early 1960s. Where European settlers did constitute a potent force, conflicts erupted as African initiatives for peaceful change were rebuffed and gave way to armed efforts. Uprisings such as Mau Mau in Kenya helped convince the British to devolve power, but outright wars were required in some contexts. In Algeria several years of fighting and, by some estimates, millions of North African casualties finally forced the French to end their rule, for example, and in the Portuguese colonies decades of struggle by African liberation forces against an intransigent regime finally led to decolonization after a coup in Lisbon in 1975.

European settlers in South Africa held out the longest. South Africa gained formal independence in 1910, when the British recognized the Union of South Africa, but devolved power resided with the European settler community: for the majority of South Africans the twentieth century was an era of struggle against European domination. Africans, Asians, and those of multiethnic heritage had limited rights, and the 1948 South African elections reduced them further. The victorious National Party, dominated by Dutch-speaking settlers calling themselves Afrikaners, imposed a policy of apartheid, or racial segregation. Apartheid reinforced segregation in everyday life, even though Europeans still depended upon African labor in the gold and diamond mines and in other industries as well as in their homes as domestic servants. Apartheid policies also aimed to create “Bantustans,” independent states in marginal areas where ethnically segregated Africans could rule but would still supply labor to a South Africa where they had no rights. The majority of South Africans protested apartheid policies, with the African National Congress (ANC) taking a leading role in organizing peaceful demonstrations in the 1950s and 1960s and then in waging a guerrilla war with its armed wing in the 1970s and 1980s. In this era, South Africans drew upon the example and support of African Americans who waged their own civil rights struggle in the United States, as well as Africans who formed a bloc of frontline states opposed to apartheid. For years the apartheid state’s security apparatus brutally suppressed dissent, but the impasse was broken when Nelson Mandela, an ANC member imprisoned for three decades and a symbol for those pushing for political change, was released from prison. Mandela helped negotiate broadly based elections in 1994, which the ANC won with huge majorities. This political history parallels experiences in African colonial contexts and is perhaps best understood within the same analytical frame.

With this last political change, contemporary Africa now can be called postcolonial, as Africans control the state apparatus in more than fifty independent states. Terms such as “neocolonialism,” however, suggest that political liberation did not necessarily produce fundamental change: Africa’s position in the global economy was structured by the rise of industrial Europe and the colonial intervention, two historical legacies that did not change with political independence. Still, globalization, a concept contested by scholars and business leaders alike, offers both challenges and opportunities for the continent. For example, the rise of China and its rapid economic growth are unleashing powerful currents throughout the continent, providing new trading partners and investors but also sometimes strengthening established political elites, as the chapter on development elaborates. Marking out distinct eras in domains besides the political also is not easy: the end of colonial rule did not immediately change the rhythms of daily life for most Africans. Independence nonetheless allowed for the imagining of new possibilities, and the last decades have witnessed changes in all areas, as the other chapters in this volume discuss at length.

Was the colonial era transformative or an interlude in a longer history? The boundaries of contemporary African states as well as the circumstances surrounding the European devolution of power to African elites set the parameters and shaped political life for at least several decades thereafter. Connections to the global economy forged during colonial rule also structured local economies no matter what policies African leaders pursued after independence. One most certainly can argue that in these two domains the colonial era was influential, but it will be necessary to wait a few more decades to see whether this legacy is enduring. In cultural domains, the colonial heritage is more difficult to tease out from ongoing African initiatives. One may point to the endurance of European languages on the continent, but much of African life is conducted in local languages. Regarding explicit European (or other non-African) influences in art, literature, religion, and other expressive domains, Africans were attracted by new ideas and practices, but they continued to draw upon local and regional cultural resources of longer standing. Africans appropriated and transformed new ideas, but they also preserved and elaborated on older ones. Dynamism and innovation are constant processes in African history, from the first transitions to food production through the peopling of the continent, the formation of states, the construction of long-distance commercial networks, and the present. Colonial domination stifled some of these expressions, but it did not destroy African culture or the vitality of African cultural production. Africans are as creative today as they were in the past, building nation-states, developing economies, and producing works of art, literature, music and other cultural expressions.

1. Hugh Trevor-Roper, “The Rise of Christian Europe,” The Listener LXX (November 28, 1963): 5.

African Cultural Heritage Sites and Landscapes. Aluka (Ithaka Harbors, Inc.). Available at www.aluka.org/page/content/heritage.jsp.

The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean World: Essays. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Available at http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africansindianocean/essays.php.

Akyeampong, Emmanuel, and Henry Louis Gates Jr., eds. 2011. Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allman, Jean, Susan Geiger, and Nakanyike Musisi, eds. 2002. Women in African Colonial Histories. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Boahen, A. Adu. 1989. African Perspectives on Colonialism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Casely-Hayford, Gus. 2012. Lost Kingdoms of Africa: Discovering Africa’s Hidden Treasures. New York: Random House.

Cooper, Frederick. 2002. Africa since 1940: The Past of the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freund, Bill. 2007. The African City: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Getz, Trevor, and Liz Clarke. 2012. Abina and the Important Men: A Graphic History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gomez, Michael. 2004. Reversing Sail: A History of the African Diaspora. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Herbert, Eugenia, and Candice Goucher. The Blooms of Banjeli: Technology and Gender in West African Ironmaking—Study Guide. Documentary Educational Resources. Available at http://der.org/resources/study-guides/blooms-of-banjeli.pdf.

Keim, Curtis. 2013. Mistaking Africa: Curiosities and Inventions of the American Mind. 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Phillipson, David. 2005. African Archaeology. 3rd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

White, Luise, Stephan Miescher, and David William Cohen, eds. 2001. African Words, African Voices: Critical Practices in Oral History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Worger, William, Nancy Clark, and Ed Alpers, eds. 2010. Africa and the West: A Documentary History, volume 1, 1441–1905, and volume 2, From Colonialism to Independence. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.