7 |

Health, Illness, and Healing in African Societies |

In African societies, as elsewhere in the world, health and illness are experienced both at the level of the individual body and at the level of the social body. Individual suffering often reveals social structures and tensions, for example when a child’s illness strains family relationships or when a treatable disease proves fatal among the poorer members of a society; healing practices may also create new kinds of community, as when a doctor and patient form a lasting bond or when the pursuit of health care spawns a social movement. The experiences associated with health, illness, and healing always reflect and affect social relationships, whether they forge, preclude, strengthen, or strain them. This chapter addresses health in sub-Saharan Africa as a product and a project of social contexts ranging in scale from the intimacy of the family to the broad power dynamics of the global political economy.

Before turning to questions of well-being and illness in specific cultural contexts, it is important to start by considering the comparative framework of biomedical assessments of the health of the world’s populations. In doing so, it becomes clear that the frequency and severity of debilitating illnesses are closely tied to political and economic power dynamics; in short, patterns of poverty are closely associated with patterns of disease. Africa’s economic position correlates with its disease profile, which includes a high prevalence of communicable diseases, high maternal mortality and infant and child mortality rates, and notable effects of pandemics. Overall health indicators reveal that health is generally poor on the continent—the average life expectancy in Africa in 2009 was fifty-four years, which makes it the world region with the lowest life expectancy rate (WHO 2011b: 54). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the leading causes of mortality in Africa (based on 2004 figures) are HIV/AIDS, lower respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and malaria, in that order. Communicable diseases are the primary threat to Africans’ health, accounting for 70 percent of the causes of death (WHO 2008a: 54).

HIV/AIDS and malaria are significant challenges to well-being on the continent and also illustrate more broadly the ways that patterns of marginalization inform health on a global scale. Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most affected by the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), in the year 2009 a total of 1.8 million people died of HIV/AIDS, 72 percent (1.3 million) of whom were Africans (UNAIDS 2010: 25). AIDS is now the leading cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa. This reflects the fact that in Africa HIV/AIDS is a generalized epidemic that affects the population as a whole (unlike in other regions of the world, where HIV transmission is primarily concentrated among particular subpopulations). There is, however, considerable regional variability in the scale of the disease’s effects. Southern Africa (Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) is the most heavily affected, accounting for 34 percent of all people living with HIV and 34 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2009, as well as 31 percent of new HIV infections. Four southern African countries have HIV prevalence rates of more than 15 percent (UNAIDS 2010: 23, 28). High rates of HIV/AIDS also increase the incidence of other diseases. For example, tuberculosis, which was previously largely under control, increased in frequency nearly fourfold between 1980 and 2000, as it became a primary opportunistic infection associated with AIDS (WHO 2008b: 52). In Southern Africa, greater than 50 percent of the tuberculosis patients who were tested were found to also be HIV positive (USAID 2011: 3).

Although Western epidemiological and public health approaches to HIV/AIDS have often stressed individual behaviors, much recent social scientific work has emphasized the social, political, and economic structures that influence susceptibility, transmission, and treatment. For example, Meredith Turshen has pointed out that structural adjustment policies exacerbated economic insecurity, increased labor migration, and disrupted family life, all of which furthered the spread of HIV/AIDS. The internal power dynamics within African societies also condition patterns of transmission. According to Anne Akeroyd, gender informs vulnerability to the disease and access to care in contexts where women often have less control over their sexual lives, are dependent on men for access to key resources, and may engage in high-risk activities in order to support themselves and their children. Some 40 percent of all adult women with HIV live in southern Africa (UNAIDS 2010: 28). The dramatic physical and population effects of HIV/AIDS and its connections to sexuality and premature death have made it a stigmatized condition in Africa, as elsewhere, which often means that the physical suffering of the disease is accompanied by the pain of social isolation. These potent social meanings and associations make HIV/AIDS a source of suspicion and a site of blame, as noted by Paul Farmer; local interpretations of and responses to the disease often involve identifying the human agents, whether the “promiscuous” individuals, malevolent sorcerers, or power-hungry Western governments, deemed responsible.

Although it has not received the same level of media coverage as HIV/AIDS, malaria has also had a profound effect on Africans’ lives. In 2010, 81 percent of worldwide malaria cases and 91 percent of malaria deaths (596,000) occurred in the African region, with children under five the most heavily affected (WHO 2011c: xiii). Although the immediate cause of malaria is infection with a parasite transmitted by mosquitoes, broader social conditions, including poverty and armed conflict, contribute significantly to the shape and severity of the pandemic. Under conditions of poverty, malaria infection and mortality are more likely due to lack of insecticides and mosquito nets, lack of pharmaceuticals that prevent and treat malaria, and poor-quality housing that does not protect its occupants against mosquitoes. Armed conflict further exacerbates the effects of malaria through forced migration into malarial areas and use of provisional housing by refugees, disruption or destruction of health care systems, alterations in vegetation that encourage the breeding of mosquitoes, and malnutrition and other physical stresses of conflict conditions. Besides poverty increasing the risk of malaria, there is also evidence of the converse relationship, that malaria increases poverty. Paula Brentlinger contends that malaria has a significant effect on human productivity in the most-affected African countries, accounting for a loss of an estimated 1.3 percent of GDP growth per year; it also takes an enormous toll at the household level in terms of time and resources spent caring for the ill. When malaria morbidity and mortality increase owing to parasite resistance to drugs such as chloroquine, treatment programs have had to either turn to more expensive remedies to combat the resistant strains, further exacerbating economic pressures, or leave patients vulnerable with inadequate treatment.

Although both local and international biomedical responses to ill health on the African continent have evolved over time, they remain for the most part inadequate. In the Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, a milestone in public health policy, members of the international community endorsed a strategy of primary health care as the means to “health for all” by the year 2000. In the succeeding decades African governments attempted to institute integrated national health programs; unfortunately, biomedical health care resources still fall far short of Alma Ata goals in the majority of African countries. Factors including weak economies and high levels of external debt have made it difficult for African countries to implement health care programs that might address the significant health challenges described above. High rates of poverty, lack of basic social services such as clean water, instability in food supplies, and the disruptions caused by political conflicts have further undermined both health and health care. African governments’ spending on health care remains low, averaging U.S. $137 per capita in 2007 (WHO 20011a: 14).

In the postcolonial period, many African countries implemented multilevel health care systems, in which both decision-making powers and resources are organized hierarchically from the ministry of health and teaching hospitals of the capital city down to provincial-level hospitals, district-level hospitals, and finally rural health clinics and posts. A review of primary health care in Africa found enormous disparities between resources allocated to urban versus rural components of these systems: although rural health clinics, dispensaries, and posts are the primary interface between people and the health care system, serving 80 percent of the population, they receive only 20 percent of the resources allocated to health services (WHO 2008b: 37). These rural health care facilities are therefore often lacking in equipment, supplies, and qualified personnel. The majority of highly trained health practitioners, especially physicians, are located in cities, and many African doctors ultimately move abroad in search of better opportunities. The Alma Ata Declaration also encouraged the utilization of traditional healers and traditional birth attendants as part of national health care programs, but to date such practitioners have for the most part not been successfully integrated into national health care systems. Some African countries have had more success with such an approach, such as Ghana, which recognizes and regulates traditional healers through its ministry of health, but many have found it difficult to bridge the disjunctures between biomedicine and local health practices in illness categories, notions of causation, treatment regimens, and practitioner training. Critics such as Brooke Schoepf question the call to integrate traditional healers into national health care programs, suggesting that the rhetoric of cultural acceptability and cost efficiency masks a lack of will to provide the most current and most effective biomedical treatments to the world’s poor.

The public health interventions enacted by international organizations and African governments in response to the most pressing health concerns provide insights into both the enormous challenges these diseases present and the powerful constraints of the political economic context in which they are embedded. Global efforts to address the toll that malaria takes in Africa and elsewhere have been spearheaded by the Roll Back Malaria initiative, established in 1998 through a partnership between WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and the World Bank. The primary interventions on which this and other antimalaria programs rely are insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapies. Although these techniques are effective against malaria and significant progress has been made in some regions, each of these measures also presents notable challenges. Insecticide-treated bed nets tend to be most utilized by the wealthier members of the societies in which they are introduced, especially when they are distributed through social marketing schemes, leaving the poorest and most vulnerable members of society still susceptible, as Paula Brentlinger has argued. Spraying insecticides in and around homes raises logistical and cost questions as well as concerns about potential toxicity. And while artemisinin-based combination therapies are the most effective current antimalarial treatment, given widespread resistance to chloroquine and other monotherapies, they are significantly more expensive than these other drugs and therefore difficult for many African nations to afford.

Yet significant progress has been made in recent years: the percentage of sub-Saharan households that own at least one insecticide-treated bed net increased from 3 percent in 2000 to 50 percent in 2011. Although this is a remarkable increase, it also creates new challenges—the effectiveness of such a treated net is estimated to last for three years, so many of the nets distributed in recent years are now in need of replacement. The number of people protected by indoor residual spraying in the African region increased sevenfold between 2005 and 2010, but this still only amounts to coverage for 11 percent of the population. In terms of diagnosis and treatment, the percentage of suspected malaria cases subjected to parasitological testing has also risen dramatically, yet in many African countries the overall testing rate remains low. However, due to intensive antimalaria campaigns, malaria-specific mortality rates in Africa fell by 33 percent between 2000 and 2010. One of the biggest obstacles to continued success is funding: WHO estimates the resources required to meet disease control and elimination targets at $5 billion per year, but current funding is only $2 billion per year and is expected to decrease in coming years (WHO 2011c: ix).

A number of scholars, such as R. Bayer, have suggested that HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment policies, in Africa and elsewhere, have been less effective than they might have been by virtue of “HIV exceptionalism”—a tendency to stress individual rights and privacies as opposed to addressing HIV/AIDS like any other infectious disease that poses a wide public health threat. Thus HIV testing in African societies has remained relatively low. James Pfeiffer has argued that HIV/AIDS education and prevention strategies in many sub-Saharan African countries have been dominated by social marketing programs in which principles of free market economics are used to promote the distribution and utilization of condoms. Critics of such programs suggest that this approach focuses exclusively on individual behavior change, ignoring the structural determinants of health behaviors, including the economic strains and worsening inequalities that were engendered by structural adjustment policies. The effectiveness of such campaigns is also debated since claimed results often rest on reported behavior collected through surveys, as opposed to any evidence of actual condom use.

Yet there are signs that recent attempts to combat HIV/AIDS are having a positive effect and treatment options for those living with HIV/AIDS have expanded considerably. Between 2001 and 2009, HIV infection rates fell by more than 25 percent in an estimated twenty-two sub-Saharan Africa countries. In southern Africa there were 32 percent fewer children newly infected and 18 percent fewer AIDS-related deaths in 2009 than in 2004. At the end of 2009, 49 percent of adults and children eligible for antiretroviral therapy were receiving it in the region overall (56 percent in eastern and southern Africa and 30 percent in western and central Africa), compared with only 2 percent in 2003 (UNAIDS 2011: 97; UNAIDS 2009: 25). However, the scope of treatment programs varies considerably among countries: by 2010, 93 percent of people in need in Botswana were receiving antiretroviral treatment, whereas in Mozambique, the figure for the same year was 40 percent (UNAIDS 2011: 98).

Although there are significant structural constraints on Africans’ health, as the above description suggests, it is important to recognize that people are not merely the passive victims of disease. Even in the face of enormous obstacles, the ill actively pursue well-being. This “quest for therapy,” as John Janzen has called it, often involves both the sufferer and his or her family and community members and may lead those in search of care and a cure to multiple and varied health practitioners. In much of Africa, the landscape of health resources comprises a multiplicity of practitioners and treatments, including biomedically trained physicians, spirit-possessed mediums, herbalists, diviners, and Christian and Muslim healers, who utilize pharmaceuticals, medicinal plants, and prayer and religious texts to treat their patients. Within this diversity, there is also a great tendency to innovate—new healing techniques, spirits, and medicinal plants are continuously discovered; new ways of combining biomedical and spiritist approaches or of combining pharmaceuticals and herbal medicines are constantly sought out. Indeed, patients appreciate such innovation and are drawn to healers who bring something new or unprecedented to the range of available services. In such a context of medical pluralism, the ill and their associates must choose among an array of possible healers, techniques, and remedies, and research shows that people often opt to utilize multiple healing regimens, whether simultaneously or sequentially. The medical pluralism of Africa is not unique. Indeed, people the world over make use of multiple healing practices. For example, in the United States a patient seeking treatment can visit a physician, a reiki master, a chiropractor, an aromatherapist, a naturopath, or a Chinese medicine specialist, as well as a variety of other medical practitioners. In addition, the U.S. government maintains the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), a unit of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to conduct research on these and other healing practices.

The cultural complexity of African healing environments also means that in many African societies there is an active and ongoing debate about the relative efficacy, legitimacy, and appropriate place within national health care plans of various kinds of health practitioners. So-called traditional healers organize themselves into professional associations, incorporate biomedical techniques into their practices, and seek out international validation. Their work has been encouraged, at least discursively, by international health organizations that seek to capitalize on healers as a human resource in contexts where there are very few biomedical health professionals relative to the population. For example, for the African nation of Mozambique, it has been estimated that there is approximately one traditional healer for every two hundred people (Green et al. 1994: 8), whereas the number of biomedical doctors is around five hundred to serve a population of twenty-three million, for a rate of approximately one physician per forty thousand people (WHO 2011b: 120). Comparable numbers exist elsewhere in Africa, and WHO estimates that about 80 percent of Africans make use of traditional healers at one point or another. In light of such figures, in 2007 the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Africa issued a Declaration on Traditional Medicine, pledging to “develop mechanisms for institutionalizing the positive aspects of traditional medicine into health systems and improve collaboration between conventional and traditional health practitioners” (WHO 2007: 3). Yet, as mentioned above, attempts at collaboration are often difficult given the epistemological differences between biomedicine and other varieties of healing, as well as the political complications of the contexts in which these debates are acted out. Thus, questions of health and healing in Africa often intersect with national and international politics regarding the organization and use of health resources, the place of “culture” in state policies, and the relationships between science and religion, the natural and spiritual worlds, and the “traditional” and the “modern.”

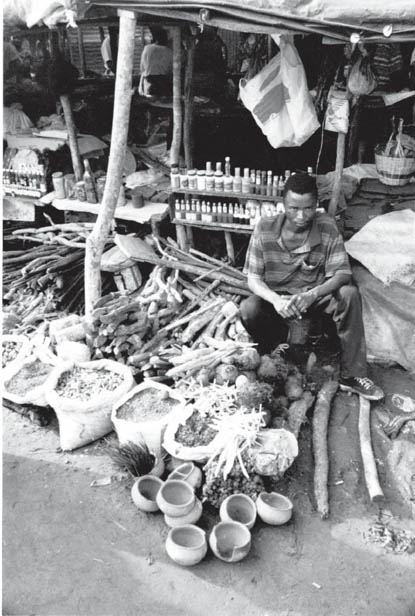

A case study of religious healing in a context of medical pluralism illustrates these and other themes regarding health and healing in sub-Saharan Africa. This case study is based on my field research in central Mozambique, in southeastern Africa. In this region, there are a variety of health resources that local people can and do turn to in response to illness. There are government health clinics or hospitals located in provincial and district capitals, and smaller health posts in rural localities. These clinics are sometimes staffed by physicians but more often are staffed by nurses or medical technicians, who examine patients and write prescriptions that can be filled at on-site pharmacies. When I visited one district capital hospital, I found that patients began to line up early in the morning and often had to wait for hours to be seen by the doctor. Just down the road from this hospital was an outdoor marketplace where a variety of foods and household goods were sold. In addition, it was possible to purchase pharmaceuticals without a prescription, many acquired across the border in Malawi, as well as herbal medicines. There were other less formal clinics scattered across the landscape in the rural areas, which often involved healers working out of their homes. At one clinic that I visited, the practitioner dispensed both herbal medicines and pharmaceuticals. Many patients came to get the penicillin injections this healer became well known for administering. Other healers dispensed exclusively plant-based medicines (constituted primarily of tree roots), drawing on the knowledge they had acquired through an apprenticeship with an older healer or relative. These healers often employed divining instruments that helped them ascertain the nature of their patient’s condition and an appropriate treatment for that person. One such healer I visited utilized an animal horn that spun on a handle; the healer posed questions about a patient’s health and the horn indicated the answers by pointing in a particular direction. Other healers diagnosed and treated their patients by means of their relationships with spirits. Some of these healers worked with the spirits of deceased ancestors. These family members, some from the distant past, others they had known personally, returned to possess the bodies of their descendants and heal through them. One such healer I met explained that her ancestor had consumed potent medicines during his lifetime that allowed him to come back after death in the form of a lion and to incorporate in her body as a powerful healing spirit. Other healers in the area had relationships with another variety of spirit; these healers were called prophets and were possessed by Christianized spirits with names such as Mary, Joseph, Lazarus, and Job. These healers wore white gowns with crosses sewn on them and utilized Bibles in their healing practices.

Figure 7.1. Vendor of traditional medicines, Maputo, Mozambique.

Tracy Luedke.

Figure 7.2. Diviner, Tete province, Mozambique.

Tracy Luedke.

Although the nonbiomedical healers working in this area were diverse in their appearances, practices, and sources of knowledge, they sometimes came together under the aegis of the Mozambican national traditional healers’ association, AMETRAMO (Associação de Medicina Tradicional de Moçambique). This professional organization first arose in the early 1990s, at an important moment in Mozambique’s history. Mozambique was a Portuguese colony and only achieved its independence in 1975 after a protracted armed struggle. After independence the new Mozambican government, led by the political party FRELIMO, which had also led the war for liberation, adopted a socialist platform. Among its policies was a mandate against what it considered to be “backward” cultural practices, including traditional healing. Instead, FRELIMO wanted to create a new, modern society based on the ideas of “scientific socialism.” During this era, healers were suppressed and many had to hide their activities.

Figure 7.3. Prophet, Tete province, Mozambique.

Tracy Luedke.

Unfortunately, shortly after independence from the Portuguese, Mozambique was once again plunged into warfare, this time at the hands of regional political regimes that sought to destabilize the new nation, including the government of Rhodesia (which later became Zimbabwe) and South Africa’s apartheid regime. The second war lasted until 1992 and did enormous damage to the country, undermining infrastructures in health, education, and transportation, and causing a great deal of suffering, dislocation, and loss of life. The effects of this warfare also destroyed the possibility of true independence on the part of Mozambique. Instead the country became dependent on foreign aid for survival and was therefore subject to the demands of international lending institutions such as the IMF. Under the conditions of a structural adjustment program instituted in the late 1980s, FRELIMO abandoned its socialist rhetoric and shifted its economic policies toward the free market. Likewise, it relaxed its restrictions on cultural practices including religion and traditional medicine. It was in this context, then, that AMETRAMO was able to claim a space for traditional medical practitioners in public dialogue. AMETRAMO’s activity in the region where I conducted fieldwork revealed the ambiguities of its relationship with FRELIMO. AMETRAMO leaders often expressed dismay at what they perceived as a lack of support and respect from the FRELIMO government and particularly from the Ministry of Health; at the same time they frequently claimed to be associated with or even to be part of the government in order to justify their authority over healers and their practices.

Of the many kinds of healing I encountered during fieldwork, I focused my research on the prophets. My interest in their practices and perspectives was motivated in part by another way that Mozambican political history has informed healing activities in this region. The period of warfare throughout the 1980s and early 1990s in Mozambique was especially brutal, with more than one million people killed and some six million displaced from their homes. In the central province of Tete, many people fled the effects of the war by crossing the borders into the neighboring countries of Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Many of the prophets I encountered in northern Tete had lived as refugees in Malawi for as many as ten years. Indeed, it was during their time in Malawi that they had first made contact with the biblical spirits with whom they worked. Before the war and the displacement it caused, I was told, there had been various kinds of healers in northern Tete, but no prophets; when Mozambicans repatriated in the years after the war ended in 1992, they brought home with them what they had encountered on the other side of the border, including their prophet spirits. Thereafter, the number of prophets and the scale of their healing activities continued to grow and created a vibrant social network. The phenomenon of prophet healing in postwar Tete province was thus one of the ways that people responded to the physical and social suffering that the war brought about—prophet healing both treated ailing bodies and engendered new kinds of sociality and community.

The nature of the social relationships that characterize the prophet community are important for understanding the healing they effect. The prophets are a network of healers and patients brought together by suffering and the desire to overcome it. Both the affliction and its treatment are understood to derive from Christianized spirits known as prophets (or aneneri in the local language, Chichewa). Prophet spirits come into an individual’s life as an illness, especially one with strange or lingering symptoms. It is often after multiple attempts at healing with a variety of practitioners that the afflicted individual makes his or her way to the compound of an established prophet healer, who diagnoses the ailment as a sign of the presence of a spirit. If the patient accepts this diagnosis and the treatments proffered, he or she is brought into a new set of relationships: with the discovering healer, who becomes his or her “mother” and mentor; with other prophets with whom this individual will regularly engage in collective ritual activities; and with the spirit or spirits who have come to inhabit his or her body. Thus the individualized path of a single prophet and her quest for healing is inextricable from the broader processes through which the community of prophets is generated and grows. Becoming a prophet involves both an individual transformation from sufferer to healer and incorporation into a social community.

Although prophet healing is quite new to northern Tete Province, it is also an example of a long-standing cultural institution across Africa that has been referred to in the anthropological literature as “cults of affliction” or ngoma. Victor Turner, in his work on religious life and ritual in Zambia, coined the phrase “cults of affliction” to describe social groups that addressed particular ailments. Turner was especially interested in the transformative rituals by which individuals became part of such groups, and he adopted a tripartite model of “rites of passage” (separation, margin, aggregation) to describe the process. He was especially interested in the middle phase, liminality—the “betwixt and between” condition that is symbolically associated with death and decay, on one hand, and with gestation and birth, on the other, and which marks the transition from one status to another. Many local and regional studies provide examples of the kind of African healing cults or communities that Turner describes.

The synthesizing work of John Janzen on comparable groups from across the southern and central regions of Africa, which he refers to as ngoma, suggested a broader and deeper framework into which to fit these various examples. Janzen drew on his own research on healing networks in Congo, South Africa, Swaziland, and Tanzania, as well as the evidence of other researchers, to identify the key features and underlying logics of a long-standing regional “ritual therapeutic institution.” Ngoma involves an experience of illness, its identification and labeling by a member of the group, and initiation into the group through a rite of passage. Ngoma practitioners often evaluate illness through spirit mediumship and recognize the roles of a diversity of spirits in illness and well-being. The most characteristic element of ngoma is the role of the “wounded healer”: through their participation in the group, patients are turned into healers, and suffering and alienation are transformed into healing and social integration. Finally, ngoma involves ritual activity, especially performance that includes singing, dancing, and drumming. Ngoma (the word for “drum” as well as the word for these ritual activities in a number of the languages of the region) is neither religion nor medicine nor politics, but a unique regional institution that recognizes and responds to misfortune in an organized, communal way.

Mozambican prophets exhibit many of these qualities, and their practices resonate strongly with this description. New prophets enter the community through illness and suffering, which leads them to seek the help of a prophet healer and to embark on a path of ritual transformation. Through engaging with the spirits, neophytes become the “wounded healers” who are in turn able to treat others. This ongoing healing work is punctuated by all-night ceremonial events full of dancing, singing, drumming, and spirit possession—expressive gatherings that bring together a larger regional network of prophets, publicly enacting the communal relationships among prophets.

If prophetic healing is a fundamentally social phenomenon, it is worth noting the key relationships at the heart of the prophet community. First is the relationship between host and spirit. Spirits cause illness in their hosts and make many demands on them. Prophets often struggle to meet these demands, which include avoiding certain foods and drinks such as pork and alcohol, buying special clothing for the spirits’ “uniforms,” constructing hospitals and churches in which the spirits might work, and staging the all-night ceremonies mentioned above. Hanging over these requests is the threat of the new illnesses spirits may inflict if their needs are not met. On the other hand, prophets recognize their spirits as a source of healing sent by God—the spirits, they explained, came to earth with the altruistic goal of helping those who suffer.

An equally important relationship is that between a new prophet and the healer who discovers his or her spirit. The healer who makes this initial discovery is referred to as the person’s “mother” (mayi), the term used regardless of the gender of the discovering healer, and the newly discovered prophet is referred to as the prophet healer’s “child” (mwana). A number of studies of healing networks have encountered kin terms, kin-like relationships, and imagery and symbolism associated with reproduction, suggesting that these groups are in some sense “reconstituted families,” as shown by Janice Boddy (1994: 416). The use of kin terms among prophets reinforces a sense of the spirit discovery process as a “birth” and a key element in a process of social reproduction.

The “mother” does not teach the newly discovered prophet to heal sick people or to use medicinal plants. All of this knowledge is transmitted directly from spirit to host. But the “mother” does act as a mentor, guiding the newly possessed person in learning to live with the spirit. This includes guidance on the lifestyle changes that the spirit demands as well as assistance with accommodating the physical effects of the spirit’s presence, which can be quite violent, especially for inexperienced newcomers. Spiritual “children” are equally important to their “mother.” These offspring will now serve their “mother” as a sign of, and active participant in, her work.

While I have been stressing the internal experiences and dynamics of “cults of affliction,” it is important to note that these groups are not closed off from the rest of the society. Although there are indeed some social boundaries, such as food taboos followed by prophets that prohibit them from eating at the homes of non-prophets, prophets spend significant time healing members of the broader society who come to their hospitals for consultations and treatments. Some of these patients are neighbors who reside nearby; others have traveled a distance, seeking out particular healers based on word-of-mouth accounts of their prowess. Many of these patients will not themselves become prophets. Although the transformation of a patient into a prophet is the central mechanism by which the prophet community grows, the spirits’ primary mandate is to help all those who suffer, and in their day-to-day work in their hospitals, prophet healers receive and treat a variety of ailments.

Figure 7.4. Prophet ceremony, Tete province, Mozambique.

Tracy Luedke.

Figure 7.5. Dancing at a ceremonial gathering of prophets, Tete province, Mozambique.

Tracy Luedke.

Examining the efforts of prophets to treat the ailments of the broader community reveals the local understandings of illness, diagnosis, and treatment that underlie not only prophet healing but the range of existing therapeutic activities in this region. There were three general categories of illness causation to which healers might attribute patients’ conditions: natural, spirit, and witchcraft. “Natural” illnesses were illnesses that “just happened.” This was the least elaborated category of causation and seemed to operate as a catchall for those conditions for which no other causation was identified. Spirit illnesses, as described above, were illnesses resulting from the presence of spirits, who afflicted their hosts as a way of demanding their compliance with the spirits’ wishes and initiating an ongoing relationship through possession. Witchcraft illnesses were those that resulted from the evil intentions of other people. These were initiated by means of certain medicinal substances and techniques, and, it was said, were usually predicated on envy, often on the part of family members or neighbors. One of the primary local varieties of witchcraft (called nchesso in Chichewa) was often referred to as a “traditional land mine”—sorcerers were said to bury medicinal substances in a path or doorway where their intended victim would walk, and treading upon them caused illness or death.

When I asked prophet healers which category of illness causation they received the most, they nearly universally reported that they received more, or even mostly, illnesses resulting from witchcraft. Most healers averred that there were both more illnesses in general and especially more witchcraft-related illnesses in the present than in the past, which they attributed to an increase in envy and hatred stemming from experiences during the war and postwar conflicts over land. Patients themselves explained that they sought out prophet healers for cases of illness in which they suspected witchcraft because they knew that prophets were especially adept at identifying it. Identifying and treating witchcraft-related illnesses was both central to the practices of prophet healing and an important part of how prophets perceived their role.

Prophet healers explained that many conditions could be either natural or the result of witchcraft, and the cause of any specific illness could be determined only through a spirit consultation, during which the spirit is able to see into the patient’s body to determine the nature and cause of illness. This was the case, for example, for malaria (malungo), a very common illness in this region and in many other parts of Africa. For natural malaria, healers offered several causes, including unsanitary conditions (lack of cleaning in the home, eating something dirty, badly prepared food, unclean water), mosquitoes (which breed in waste or stagnant water near the home during the rainy season), and exposure to cold temperatures. Malaria provoked by witchcraft was understood to be contracted in the same manner as other witchcraft illnesses, that is, through the use of medicinal substances against the intended victim, and it was considered far more dangerous than natural malaria, leading more rapidly to death. In making these distinctions between witchcraft and natural illnesses, healers were also identifying the separate domains and strengths of traditional medicine versus biomedicine, and the relative social roles of different varieties of healers in a medically plural society. They suggested that witchcraft illnesses could be treated only by traditional healers. If someone suffering from such an illness went to a government clinic and took the prescribed pharmaceuticals, these would at best be ineffective and at worst turn to poison. This was why patients carefully monitored illness symptoms and the effects (or lack thereof) of various treatments received; if they perceived the signs of an “unnatural” illness, it was necessary to visit a traditional healer.

The illness histories of patients I met at prophet healers’ hospitals as they sought assistance for ongoing health problems trace the routes that particular patients traveled among a variety of healers and treatments, and their responses to the conflicting explanations and variably effective treatments they encountered along the way. The three case studies presented here also demonstrate the ways prophet healing strengthens some relationships and challenges others. The forces of concord and discord are in fact deployed within the same ritual sphere, in this case the weekly spirit consultation session held at the hospital of husband and wife prophet healers Paulo and Mariya.

Patient 1. When we met, Patient 1 had been at the hospital of Paulo and Mariya for three days, trying to resolve an illness that had plagued her for six years with pains in her legs, heart, and stomach. Before arriving at Paulo’s she had been to five other traditional healers, all herbalists, all of whom said she had stepped on a “traditional land mine” (nchesso). They treated her, but the treatments did not work. She felt better while she was at their hospitals, but as soon as she went home, the illness returned. She had also visited a stall at the market near her home, where she purchased several kinds of pills for pain and stomach upset, but these too were ineffective. In her initial consultation at Paulo and Mariya’s, the spirit explained that her illness was the result of witchcraft. Someone had taken a photograph of her and some thread from clothing she had worn and mixed it with dirt from the cemetery and a medicinal substance, and that is how the illness began.

Patient 2. Patient 2 was a nine-month-old child, brought by his young mother. She and the child had been at Paulo and Mariya’s hospital for six days. The child had been suffering from fever, cough, and respiratory problems for a week. In response to the illness, the mother had first taken the child to the government clinic, where he was diagnosed with malaria and anemia and given pills and intravenous fluids, which the mother said were chloroquine and penicillin. The child seemed to improve at first, but within a few days the condition worsened to the point that the mother was afraid the child would die. Seeing this, she brought the child to Paulo and Mariya in the middle of the night and a consultation was done, during which the spirit explained that the child had malaria and anemia provoked by witchcraft, and that the child should stay to receive treatment. For the previous six days as a patient at Paulo and Mariya’s hospital the child had received plant-based medicines and was now much better.

The mother explained that she knew of Paulo because she lived nearby and had already used his services on a previous occasion. On the previous visit she had brought another one of her children who was sick at the time. That child, in fact, ended up dying at Paulo and Mariya’s. She explained that this occurred because she had spent too much time taking the child to other healers first, so by the time she brought the child to Paulo and Mariya’s, he was already close to death and finally passed away there. However, she said, she had seen many other patients with serious illnesses leave their hospital cured and so had faith that they could help the child for whom she was currently seeking treatment. She also explained that she decided to come to Paulo and Mariya’s because she had tried at the government hospital and it did not work, which led her to suspect that this was the kind of illness that only traditional healers could treat.

Patient 3. Patient 3 was a young man in his late teens. He explained that lightning had struck near him as he sat drinking beer with friends. Soon after the lightning strike he began to feel pains throughout his body, his bones hurt, and he felt twinges in his belly. He had not used any biomedical treatments before arriving at Paulo and Mariya’s, because, he said, he perceived that this was an illness sent by an enemy, and he knew it was necessary to go directly to a traditional healer. He thought so because a few days before the lightning strike there had arisen a dispute among several of his family members, and he concluded that the lightning was sent against him as a result of this.

After their initial treatments, patients staying at the hospital of Paulo and Mariya received weekly spirit consultations to monitor their progress. These were typically performed on Saturdays, the primary day on which the healers received and consulted with patients. On one such Saturday, I was able to observe the consultations for the patients described above. On this particular morning, about forty people assembled in Paulo and Mariya’s hospital, a large room decorated with banners and crosses in a building that included several smaller rooms where patients stayed. The assembled participants included eight of Paulo and Mariya’s spiritual “children” (who occupied one corner and acted as a sort of chorus, accompanying the healers in singing hymns); six new patients anticipating their first consultations; about fifteen returning patients in ongoing treatment, there for a checkup and to renew their medications; and various family members accompanying the ill. Thus within this one ritual space were represented individuals at all stages of incorporation into the social body of the ngoma, from lay outsiders (new patients and their families) to long-standing insiders (”children” of the healers who now participated in healing activities). The participants sat along the walls, leaving the center of the room open for the doctors to work from.

Paulo and Mariya stepped into the hospital. Paulo was wearing a long red gown and a floppy orange hat with a cross on it and many brightly colored sashes tied around it and streaming down his back. He carried a Bible and a whisk made of an animal tail. Mariya wore a white smock, white pants, and a white headscarf, all decorated with blue crosses. She held a small mirror in each hand, and there were whistles and crucifixes hanging from her neck. The pair immediately began to sing animatedly, and those assembled joined in.

Paulo dipped at the knees, swaying and spinning as he sang. Mariya began to tremble and shake, jumping and gesticulating. Although she was otherwise quite calm and reserved, with the spirit in her body she became bold and aggressive, talking loudly and directing the proceedings. She led the group in a song, during which she hopped and danced in a lively, jittery way. Mariya began to do consultations for the assembled patients, each patient coming forward to stand when it was his or her turn. After she had performed a series of consultations, Paulo took over and carried out a number of consultations himself, a tag-team arrangement that reflected the rigor of the work: it would have been difficult for one person to sustain the frantic energy and support the draining presence of the spirits for the whole session, which lasted almost four hours.

It was time for the consultation of Patient 1, the young woman who hoped to resolve her long-term illness. Her mother stood at her side during the consultation. Mariya’s spirit spoke, recounting the girl’s symptoms and treatments. She went on to say, “These problems aren’t natural, and she doesn’t have AIDS, as some other people in the area where she lives have said. I can see that you [the mother] and others have thought that this illness is AIDS. If it were AIDS, I would tell you. This illness comes from witchcraft.” The person who sent the illness, she explained, was a member of the girl’s family on her mother’s side. The girl’s mother, she said, was considered rich and arrogant by her neighbors and family members, which had encouraged the attack against her daughter. The spirit reassured the girl and her mother that she would be able to cure this condition, that her medicines would cleanse the girl’s body and make her well again.

Patient 2, the young woman with a sick infant who had lost another child at Paulo and Mariya’s in the past, was the next to be addressed by the spirit. The spirit declared that the child’s health problems were a result of witchcraft perpetrated by a group of neighbors intent on killing the child. The spirit explained that this group had fed the child dirt from a cemetery, which brought on the pain and coughing. Mariya assured the mother that the child would recover with her help and encouraged her also to take medicines to protect her home from further attacks.

Patient 3, the young man who had experienced a lightning strike, stood for his consultation, and his parents stood at his side. Mariya explained that the lightning that struck near the boy had caused his feelings of weakness and mental confusion. She further explained that this lightning was sent by an uncle with whom the parents were involved in a dispute over land. Mariya said she knew that family members of the boy and local community leaders awaited her pronouncements on this case so they would know whom to blame, but she declined to become embroiled in these familial politics. Instead, she declared, she planned to focus on the boy’s well-being—he would remain under her care until his health was fully recuperated.

The patients described here, and others like them, were pursuing wellness in a context of great uncertainty. Neither the nature of the illnesses at hand nor which variety of healer or treatment might be effective was known, and the threat of incapacitation and death was ever-present. This led the patients to seek out multiple healers and remedies, both formal and informal, biomedical and spirit-based, involving both pharmaceuticals and medicinal plants. These cases reveal the limitations of available health services—the struggles the ill go through in pursuit of wellness and the variable results of their quests. These cases also demonstrate the locally perceived insight that illness and healing are political, involving as they do interpersonal power struggles, disputes over resources, manipulation of potent forces, and the forging and breaking of social alliances. Although from a biomedical perspective the notion of witchcraft as an explanation for illness and a basis for treatment may seem erroneous, as an analytical framework, it addresses individual bodily suffering in its sociopolitical context, reminding people that illness and possibilities for overcoming it are more than biological questions.

The profundity of the health needs and the complexity of the medically plural response to suffering in Africa present an important set of challenges. It is crucial that significant health resources be directed toward improving the well-being of Africans, and it is also crucial that the insights of local analyses of health and approaches to healing be recognized. The three examples of patients presented here demonstrate the complicated social field in which illness experiences and responses are embedded: the biomedical disease categories and social threats of HIV/AIDS and malaria appear together with discussions of witchcraft and spirits; chloroquine and penicillin cross paths with locally produced, plant-based medicines; land disputes and intrafamilial tensions intersect with physical pain; the patterns of child mortality that appear in globally circulated public health literatures instantiate in one mother’s struggle to keep her child alive. The networks of healers and patients described here as ngoma are one significant forum across Africa in which people assess and respond to illness. Ngoma exists alongside and intersects with multiple varieties of healers and healing practices, which draw from biomedicine, Christianity and Islam, and possession and divination, and which constantly stretch the boundaries between and around local medical practices with innovative new techniques.

Ngoma healing networks exemplify a fundamental principle of many kinds of African healing: the inherently social nature of health, illness, and healing and the push and pull of forces of cohesion and division within them. Given the broader social circumstances and structural constraints that inform health in sub-Saharan Africa—the stresses on individual and social bodies wrought by poverty, armed conflict, and the power dynamics of the global political economy—such healing activities constitute important interpretations of, and responses to, illness. In addressing the effects of powerful health threats including malaria and HIV/AIDS on local lives, families, and communities, African healers such as the prophets of Mozambique confront and assert analytical and practical agency regarding forces that are in many ways more powerful than themselves. The significant health challenges Africa faces require, and will continue to require, political will, incisive analysis, and creative problem solving at local, national, and global levels.

UNAIDS. 2009. AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva: UNAIDS and WHO.

———. 2010. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS.

———. 2011. Global HIV/AIDS Response: Epidemic Update and Health Sector Progress toward Universal Access. Geneva: WHO.

USAID. 2011. HIV/AIDS Health Profile, Sub-Saharan Africa. Available at www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/aids.

WHO. 2007. AfroNews 8(3): September–December 2007. Brazzaville, Congo: WHO Regional Office for Africa.

———. 2008a. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD): 2004 Update. Geneva: WHO.

———. 2008b. Report on the Review of Primary Health Care in the African Region. Brazzaville, Congo: WHO Regional Office for Africa.

———. 2011a. Health Situation Analysis in the African Region: Atlas of Health Statistics 2011. Geneva: WHO.

———. 2011b. World Health Statistics 2011. Geneva: WHO.

———. 2011c. World Malaria Report 2011. Geneva: WHO.

Akeroyd, Anne. 1996. Some Gendered and Occupational Aspects of HIV and AIDS in Eastern and Southern Africa: Changes. Continuities, and Issues for Further Consideration at the End of the First Decade. Occasional Papers, No. 60. Centre of African Studies, Edinburgh University.

Bayer, R. 1991. “Public Health Policy and the AIDS Epidemic: An End to HIV Exceptionalism?” New England Journal of Medicine 324: 1500–1504.

Boddy, Janice. 1994. “Spirit Possession Revisited: Beyond Instrumentality.” Annual Review of Anthropology 23: 407–34.

Brentlinger, Paula E. 2006. “Health, Human Rights, and Malaria Control: Historical Background and Current Challenges.” Health and Human Rights 9(2): 11–38.

Farmer, Paul. 1992. AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Green, Edward C., Annemarie Jurg, and Armando Djedje. 1994. “The Snake in the Stomach: Child Diarrhea in Central Mozambique.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 8(1): 4–24.

Janzen, John. 1978. The Quest for Therapy: Medical Pluralism in Lower Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 1992. Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Last, Murray, and G. L. Chavunduka, eds. 1986. The Professionalization of African Medicine. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Pfeiffer, James. 2004. “Condom Social Marketing, Pentecostalism, and Structural Adjustment in Mozambique: A Clash of AIDS Prevention Messages.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 18(1): 77–103.

Schoepf, Brooke G. 2001. “International AIDS Research in Anthropology: Taking a Critical Perspective on the Crisis.” Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 335–61.

Turner, Victor. 1968. The Drums of Affliction. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Turshen, Meredith. 1998. “The Political Ecology of AIDS in Africa.” In The Political Economy of AIDS. ed. Merrill Singer. Amityville, NY: Baywood.

West, Harry G., and Tracy J. Luedke. 2006. “Healing Divides: Therapeutic Border Work in Southeast Africa.” In Borders and Healers: Brokering Therapeutic Resources in Southeast Africa, ed. Tracy J. Luedke and Harry G. West. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.