8 |

Visual Arts in Africa |

African art has been made for many thousands of years, undergoing numerous major and often dramatic changes through the centuries and right up until today. Its forms and materials, meanings and functions have always been tremendously varied, deeply imaginative, and dynamically part of people’s individual and social lives. Frequently stunning and formally sophisticated, it has been collected by Westerners for at least half a millennium and in fact profoundly influenced the modern history of European art.

The study of African art has changed drastically over time. For centuries Europeans viewed it as the exotic production of strange societies, which did not warrant much explanation. Not until the twentieth century was it seen to reflect aspects of African social, spiritual, and political organization, although contextual information was minimal. As the twentieth century progressed, and especially since the 1960s, art historians and anthropologists have developed increasingly sophisticated approaches to learning about and understanding African art’s subtleties, complexities, and dynamic involvement with society and culture.

To simplify a complex topic, three categories of African art are presented: traditional, popular, and fine or contemporary art.

Traditional art consists of the masks, figures, and other objects made and used in local African contexts involving spiritual practices, initiations, or demonstrations of prestige and status, including leadership activities. Frequently carved of wood, traditional art is intimately bound to the community of which it is a part, both reflecting and shaping beliefs and practices. For most traditional art now in Western museums and collections, the names of the artists have not been preserved, so objects are usually identified with specific ethnic groups—thus, they are referenced as a Dogon figure or a Yoruba mask, to cite two examples.

Popular art constitutes many forms of artistic expression that came into existence with the advent of colonialism. Popular artists may use materials not generally associated with traditional art, such as canvas, cardboard, and plastic-coated wire. Popular art is intended to be seen by anyone; it is not associated with sacred or secret institutions, and it is frequently made to entertain or to advertise.

Contemporary or fine art is art that was made beginning in the twentieth century as a means of personal expression and for aesthetic display. The major difference between fine art and the other categories is that it is not made to be used in localized contexts or as souvenirs, as is traditional and much popular art; instead, artists making contemporary art do so with the intention that it will be displayed as art and—most hope—appreciated by a global public. In addition, unlike most traditional and popular art, nearly all examples of fine art can be associated with the names of the male and female artists who created them.

These categories convey the fact that there are differences among the myriad forms of African art and expressive culture. But there is a great deal of formal and conceptual overlap among them, and, in fact, scholars of African art have struggled for decades with how best to differentiate them. We have selected three categories that are widely accepted, but they should not be conceived of as rigid compartments. Instead, they are a framework for beginning to understand and appreciate the diversity that constitutes African art today.

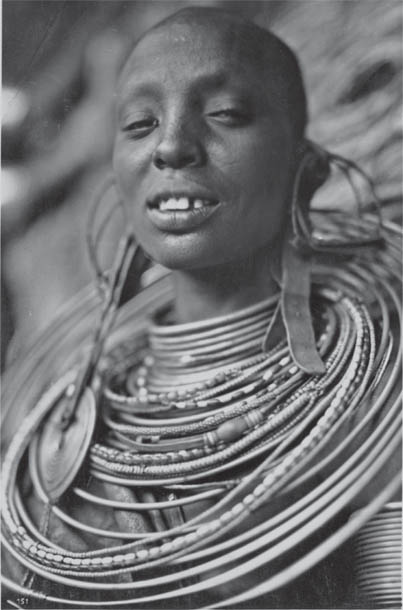

To many people, traditional African art consists of masks and figures that come primarily from two large regions: the areas around the Niger and Benue Rivers in West Africa and the Congo River basin in Central Africa. While masks and figures have been (and frequently continue to be) used by many peoples in those regions, they by no means exhaust the diversity and richness of traditional African art, but rather reflect the interest of foreign collectors. Indeed, nonfigural arts are the primary visual art traditions for many African peoples, particularly those of eastern and southern Africa. The Maasai, a pastoral people who live in Kenya and Tanzania, for example, do not make masks or figures for their own use; however, they are known worldwide for their beautiful and innovative beaded jewelry (figure 8.1). In addition to dress and body decoration, nonfigural traditional arts include furniture, such as stools and headrests; other household objects, including ceramic vessels and baskets; and even weapons—objects that Westerners often place in the category of “crafts.” These arts are also found in the areas that produce figural sculpture, creating a rich, complex array of visual traditions in many parts of the continent. In fact, for most people, nonfigural arts are far more common and seen far more frequently than masks and figures, which may be viewed only on certain occasions or by particular people.

Traditional African art is most often identified by the ethnic group that made and used it. Throughout much of the scholarly literature and in museum exhibitions, specific styles, or the visual qualities of artworks, are associated with particular ethnic groups. For example, elaborate scarification carved in relief on a figure’s face, neck, and torso is one element of the sculptural style that is associated with the Luluwa of Democratic Republic of the Congo (plate 8.1). But many ethnic groups, such as the Igbo in Nigeria and the Bamana in Mali, make art in several styles. In addition, ethnic boundaries are often porous, not only in most cities, which tend to attract people from many areas, but also in the margins of a group’s homeland, as well as in many rural regions where spaces are shared by more than one group and a great deal of interaction takes place, from friendships and intermarriage to complementary use of land through farming and grazing and joint business ventures.

Figure 8.1. Maasai woman in Kenya, 1924/1941. Casimir Zagourski African postcards, 1924–1941 (inclusive).

Manuscripts & Archives, Yale University.

In addition, long-distance travel and commerce are an important part of African history, as are expansionistic politics, and the forms, ideas, and functions of art are therefore often highly mobile and interactive. Numerous ethnic groups share many types of art, and often the appearance and functions of specific examples are very similar. Figural sculptures with spiritually charged attachments are a good example. They range from Nigeria and Cameroon across Democratic Republic of the Congo and into Angola to the south and Tanzania to the east (plate 8.2). Huge horizontal masks, found from the coast in Guinea to central Nigeria near Lake Chad, are another excellent example (plate 8.3).

Ownership of traditional artworks can be complex. In some cases, individual ownership is the rule. In Mali, for instance, carved wooden door locks, often sculpted into abstract animals or people, secure people’s private rooms. Other objects, though, may be owned by a family or clan. Near the coast of northern Tanzania, Zaramo girls are given small abstract female figures during the period of seclusion that marks their initiation into womanhood (plate 8.4). When not in use, such a figure is kept by a senior woman on the paternal side of the family, who holds it in trust as an important family heirloom. In still other cases, such as the masks worn at performances by Bamana youth associations (plate 8.5), religious or social associations or even entire communities “own” artworks, with priests or leaders in charge of their safekeeping.

Wood is the medium most often associated with traditional African art. The traditional carving tool is the adze, which resembles an axe but with its blade perpendicular to the handle. After carving, some objects are painted. Originally, locally made vegetal and mineral pigments were used. Today, factory-made paints are often preferred for their brilliant color and greater permanence. To Westerners accustomed to art created to be permanent, wood may seem an odd choice of material, given its relatively quick deterioration from climate and insects in most of Africa. With few exceptions, however, objects were not meant to last indefinitely—renewal was both expected and desired.

An equally important material is iron. Among some peoples, such as the Dogon and Bamana, beautiful iron lamps and staffs are testament to blacksmiths’ technical skills and aesthetic acumen. More often, however, their products enable other things to be done: fields to be farmed with iron hoes, wood to be carved with iron-bladed adzes. In the hands of master smiths, even these seemingly mundane implements can attain a beauty of form and workmanship that places them above the ordinary.

Traditional African art in clay includes bowls, pots, and other vessels and freestanding figures. Like metal, it is nonperishable, and terra-cotta figures from Nok, Nigeria, are the oldest sculptural tradition known from south of the Sahara (plate 8.6). Most ceramics are more utilitarian vessels, formed by hand, using coil, molding, and slab methods. As plastic and enamel containers have become widely available, pottery making has decreased in some areas, though it still thrives in others and has now become highly desired by collectors.

Cloth is woven from local cotton, wool, and silk, and from imported fibers, such as rayon. In earlier times, barkcloth was made in some areas. Most fabric is strip-woven; that is, strips of cloth, ranging from a few inches to two feet in width, are woven on a loom and then sewn together to make a large rectangle (plate 8.7). Woven patterns, painting, stamping, resist dyeing, embroidery, and appliqué are all used to make African cloth among the most beautiful, complex, and colorful in the world. Factory-made cloth, both imported and manufactured all over the continent, is also popular. Printed images may commemorate special occasions and, particularly in East Africa, often include proverbs, combining verbal and visual arts.

Other materials, such as gold, copper-based alloys, and ivory, are prestige materials: their use generally signifies wealth or importance in the religious or political sphere. This was the case, for instance, in the West African kingdom of Benin, where brass was the prerogative of royalty; altars honoring deceased kings displayed brass sculpture, such as commemorative heads (plate 8.8). In many parts of the continent, elephants were associated with leadership because of their size and strength, making elephant ivory carved into horns, whistles (plate 8.9), jewelry, containers, and charms especially appropriate insignia of political power.

Traditional African sculptors have not used stone extensively, except in about half a dozen areas (in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia). None of those traditions continues to the present day. However, in at least one of these areas, Zimbabwe, stone carving has been successfully revived for the art gallery and tourist markets.

Traditional arts are predominantly three-dimensional, with few examples of painting, drawing, and engraving, which are prominent in the popular and modern/contemporary arts. But painting and engraving on the walls of caves and rock shelters in southern Africa and in what is now the Sahara Desert are the oldest known examples of art in Africa. More recently, the Dogon of Mali paint sacred symbols, encapsulating important aspects of their ethos, on rock, as do Sukuma associations of snake handlers and snakebite curers in Tanzania. Stunning designs are painted on the facades of homes from Burkina Faso to Cameroon and South Africa. Aside from decorating sculpture, however, perhaps the most common use of paint is in decorating the human body, not only for beauty but also to indicate important social and spiritual states and transitions.

In traditional African art, certain media and techniques are associated with each gender. Metalworking and carving, whether in wood, ivory, or stone, are the domains of men in virtually all societies. One exception is among the Turkana of Kenya, where women make wooden containers that are among the most elegant bowl forms in the world. Pottery is generally considered a woman’s art, and in some societies the potters are most likely to be the wives of blacksmiths. Again there are exceptions, such as among certain groups in eastern Nigeria, where women make pots for food and water, while men make anthropomorphic ritual vessels used in divination and healing.

Weaving is practiced by men or women, depending upon the area and, sometimes, the loom type. In parts of West Africa, men weave very long, narrow strips of cloth on horizontal looms, while women in the same areas use broader vertical looms to make wider panels of cloth. Men weave raffia cloth in central Africa, while in Madagascar women are the weavers.

Whatever their gender, people creating traditional art, like artists worldwide, undergo training and are recognized in their chosen fields. This statement belies a common but completely false stereotype about African art: namely, that art was made by anonymous, untutored men and women. This stereotype says much about Western prejudices and misconceptions. First, most traditional African art is anonymous outside the continent only because collectors did not record the artists’ names. In most cases within the African setting, the names of artists are well known, whether the objects are ritually oriented or utilitarian. Truly great artists can develop such reputations that people travel great distances to acquire objects made by them. Second, the myth of the untutored artist may fit romantic Western ideas about the “noble savage,” but the objects reveal a sophisticated understanding of materials, techniques, and composition. In many cases, training is informal. Elsewhere, training requires formal apprenticeship, sometimes lasting many years. Among the Bamana, for example, blacksmiths are also the woodcarvers, and smithing is a hereditary occupation. By the time a young boy officially begins his apprenticeship, he will already have spent numerous hours at his father’s forge, observing and performing small tasks. His formal apprenticeship may last as long as seven or eight years, as he learns first to work the bellows, then to carve wood, and finally to forge iron.

With a few exceptions, most traditional artists create part-time, as ways to supplement a family’s income. Of course, famous artists may earn enough money to make it worthwhile for other family members to shoulder additional farming or herding responsibilities, leaving the artists free to devote more time to their art.

Artists often build up stocks of utilitarian objects, which they sell from their homes or take to market, but masks, figures, and the most prestigious utilitarian objects are generally made on individual order. Clients may explain in detail what they want, they may specify the type of object and leave the details up to the artist, or artist and client may negotiate the specifics of a commission.

The older the art, the harder it is to know much about it. This is particularly true for Africa, where many art forms are highly perishable, written documentation is infrequent, and archeology is an expensive undertaking, not always considered as important as a country’s other pressing needs. Thus, our knowledge of ancient African art is patchy and incomplete. The evidence we do have from permanent materials, however, suggests rich and varied traditions.

Paintings from a rock shelter known as Apollo 11 in the mountains of the southern Namibian desert are the oldest known artworks from Africa, dating to before 21,000 BCE. Ancient rock paintings and engravings are also found in other parts of southern and eastern Africa, and though determining the age of many remains problematic, evidence suggests millennia-old traditions that in some areas continued well into the time of European contact. Well north, in what is now the central Sahara Desert, rock paintings have been dated using carbon-14 to around 10,000 BCE. Wherever they are located, these paintings and engravings consist of abstract motifs as well as marvelous images of animals and scenes of hunting and spiritual or social activities. Saharan paintings also record the coming of the horse and the camel to the continent, as well as the ancient use of masks. More recent ones in the south depict the use of European firearms. While these paintings and engravings are generally considered to reflect beliefs about the world and cosmos, there is little evidence for definitive explanations of specifics.

Architecture must also be included among the arts for which a long history is evident. Dry stone architecture was found from the first millennium CE at Koumbi Saleh, putative capital of the ancient Ghana Empire, a building tradition that apparently began by the middle of the second millennium BCE in the Dhar Tichitt region of central Mauritania. In southern Africa between 1000 and 1500 CE, the civilization now known as Great Zimbabwe developed complex networks of production and trade, a ruling elite, and a complex and beautifully constructed system of stone block architecture, which was used to create several regional centers. Remains of city and mosque architecture cut from coral masonry blocks and dating from the same time or earlier are also found along the East African Swahili coast. Also from around the same time, or possibly earlier, Ethiopian Christian churches were carved into monolithic rock. Elsewhere, materials that require regular upkeep and refurbishment, such as clay, wood, and thatch, have been the norm, with the result that our understanding of the history of that architecture is limited.

Thanks to historical happenstance and archeology, we know most about the ancient arts of Nigeria. The oldest sculpture yet found from sub-Saharan Africa is clay and dates from between 500 BCE and 500 CE, though it may have begun considerably earlier (plate 8.6). It comes from a Nigerian culture dubbed Nok, after a town where much of it was found. Details, such as the large bundles of beads depicted on male figures, suggest leadership portraiture. The elegant simplicity of Nok figures contrasts sharply with the elaborate metalwork dating to the ninth century CE at the Igbo Ukwu site in southeastern Nigeria. There, large quantities of remarkable cast bronze sculptures were found in shrine and burial contexts. Made by the ancestors of today’s Igbo peoples, these pieces include figures of animals and human heads, containers, and replicas of objects such as shells and calabashes. They were associated with a complex, widespread, and powerful spiritual-political organization. Leadership combining political and spiritual capabilities was also important in areas further to the west, in a complex, loose, and constantly competing confederacy of city-states grounded in commerce and expansionistic ambition that emerged as early as the late first millennium BCE. The hub of these polities was Ife, which between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries CE sponsored spectacular leadership arts in clay and brass, including terra-cotta heads, quite possibly portraits of leaders, which are a subtle combination of naturalism and idealized abstraction (plate 8.10). Later, in the same broad area, the kingdom of Benin flourished from the fifteenth century until the British defeated it in 1897. Benin sculpture shows us how rich and multifaceted art in the service of the state can be, with artists working for the king to create shrine objects such as brass heads commemorating deceased kings (plate 8.8) as well as palace furnishings and royal regalia. Much Benin art, pillaged after Britain’s attack, was auctioned in Europe, and it played an important role in opening the eyes of Western artists to the power of African creativity.

Findings from other parts of the continent suggest that Nigeria’s early arts were not unique. In Mali’s Middle Niger region, for example, an iconographically complex array of terra-cotta figures (plate 8.11) came to the attention of the outside world in the mid-twentieth century. Usually dated to the twelfth or thirteenth century, the figures have been looted in large numbers and sold to Europe and North America for half a century, but precious few have been found in systematic archeological excavations, so information about them is extremely limited. Most depict individuals, couples, and snakes, and they may have served on ancestor shrines or as household guardians.

Regular contact with Europeans brought new materials, such as oil paint and chemical dyes, and made others, such as brass and glass beads, more widely available. Changing practices and beliefs led to the creation of new art forms and the elimination of others. In addition, new art markets were created. Afro-Portuguese ivories are a good example. In coastal West Africa, fifteenth-century Portuguese explorers and traders were so taken with the sculpture that they saw in the region of present-day Sierra Leone and Guinea that they commissioned local artists to carve ivory objects, such as spoons, salt cellars (plate 8.12), decorative hunters’ horns, and pyxes for export back to Europe. Though European in form, this earliest tourist art is carved in a style that is clearly African.

Unlike many popular and contemporary arts, traditional arts have been used in specific contexts, from which they derive their importance and meaning. Broadly speaking, they involve spiritual practices, initiations, or demonstrations of prestige and status. Most frequently, a single artwork reaches across at least two of these categories, if not all.

Much traditional African art is intimately connected with what John Hanson calls “religions with African roots” (see chapter 5). Whatever the specifics, most of these locally rooted religions share a belief that deities, spirits, or potent natural forces have the power to affect people, communities, or societies. It is not surprising, then, that practices and rituals, many of which involve masks, figures, and other objects, were developed to encourage these powers to enhance human life.

The Yoruba, who live in Nigeria and the Republic of Benin, have one of Africa’s best-known pantheons, which includes hundreds of deities (orisa), and often use artworks in spiritual associations devoted to them. For example, figural staffs or wands are associated with Esu, an orisa who is both messenger and trickster, embodying concepts of contrast, provocation, and contradiction (plate 8.13). Esu helps people by carrying their offerings to the other gods; at the same time, he has a provocative nature, causing misfortune and havoc to those who he feels do not make appropriate sacrifices, properly acknowledge his powers, or follow Yoruba moral standards. Sculpture dedicated to him frequently incorporates cowrie shells, which contrast with the darkness of the wood, a visual restatement of the oppositions that are part of the deity’s character. Further, as a former medium of exchange, cowries remind viewers of the disagreements that money can engender, as well as the generosity of the devotee.

Artworks relating to ancestor spirits are numerous and well known, providing the opportunity to cherish the memories of beloved relatives while gaining some influence in the spirit realm by showing respect to the deceased who reside there. In Gabon, for example, Kota people both honored their ancestors and appealed for their protection with abstract figures that were set in baskets holding bone relics of a clan’s ancestors and placed in a community shrine enclosure (plate 8.14). Also believed to protect the relics, the figures were carved of wood and then covered with copper and brass, which made the sculptures more valuable and more beautiful, thereby pleasing the spirits.

Among the Mende and nearby peoples of coastal Sierra Leone and Liberia, wilderness spirits are represented in the masks of an association called Sande. Members of Sande initiate young girls into adulthood; train them to be good mothers, wives, and citizens; and teach them the intricacies of social and spiritual life. The society also provides older members with an infrastructure of beliefs and activities that connect to aspects of broader community life, offering women significant amounts of power and authority. During association ceremonies, members dance wearing beautiful jet-black helmet masks (plate 8.15) that represent wilderness spirits with whom the individual mask owners have established intimate and beneficial relationships. The masks are considered to be the epitome of beauty, which reflects upon the nature of the spirit and also upon the accomplishment and capacity of the woman who owns the mask.

More generalized forces and energies are also important in local African religions, and artworks often serve as the vehicles for accumulating and activating them. These forces, variously described as the energy that makes the universe possible, the force behind all activities, and the power that allows and constitutes organic life, can only be managed by someone trained to do so: these are the priests, herbal doctors, and divination experts of African societies, as well as the independent sorcerers, who invoke their power to benefit or harm others.

In West Africa, masks are frequently designed to accumulate these powers. Good examples are those belonging to the Mande Kòmò associations (plate 8.3), masks that are believed to have the power to destroy antisocial sorcerers and to protect communities from malevolent wilderness spirits. Mask owners are Kòmò leaders who, like the Mende Sande mask owners, also have close relationships with wilderness spirits. Designed to rest horizontally over a dancer’s head, Kòmò masks depict the energies they embody. Their mouths and feathers represent the deep knowledge of the world possessed by hyenas and birds. Their horns suggest wilderness and the raw energies that abound there. The murky coatings of sacrificial materials add power and suggest the ambiguity and indeterminate, secret nature of the energies at work in the mask.

Across Central Africa, figures with all sorts of attachments, such as mirrors, horns, nails, shells, beads, and herbal medicines, also harness power to do the bidding of individuals and groups. Among the people who use them are the Kongo, Bete, Teke, Kuba, and Songye (plate 8.2). The figures vary in size, gesture, and attachments, according to the powers they are supposed to harness and the activities they are supposed to help people undertake. Some cure illnesses, others block misfortune, and still others seek and punish those who commit a crime or try to inflict misfortune on others.

In Africa, artworks play important roles in initiations, the ceremonies that mark a change in status, position, or role for an individual or group. In most traditional African societies, nearly every person participates in at least one initiation: that which marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. In the Bissagos Islands, off the coast of Guinea, for example, boys undergo a two-part initiation that includes masquerade. At certain stages, the boys wear masks depicting ferocious and predatory sea creatures (plate 8.16), emphasizing the fact that they are at the height of their physical prowess and strength but as yet do not have the knowledge and wisdom necessary for success as adults in the civilized world. In other parts of Africa, masks are part of ceremonies presenting information boys must acquire to be considered adults, or masks may represent a monster that devours the boys and allows them to be reborn as men. In many places masquerades are part of the celebrations that welcome initiation participants back into their communities as new adults.

Initiations may also mark the acceptance of certain roles or positions within a society, such as when rulers or priests take office. A Kongo chief undergoes an elaborate initiation into office, which includes a period of seclusion and an ordeal intended to ascertain the approval of spiritual forces. Upon successful completion of the ordeal, the chief is given particular objects, including a sword and a staff, as symbols of his leadership. Finally, men and women may be initiated if they choose to join associations or societies that are dedicated to particular causes or ideals. The Bwami association, which most Lega men and women in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo joined, is a complex, multilevel institution dedicated to the development of moral behavior. Advancement within the society is based on payments and demonstrations of knowledge appropriate to each rank. An initiate learns the necessary information from a variety of sources, including proverbs, songs, and the manipulation of different objects, both natural and human-made. For some levels, these objects include wooden and ivory figures (plate 8.17) and masks, which become not only educational tools but also emblems of rank and status.

Many traditional arts indicate social, political, or economic status. Frequently known as prestige arts, they are identified by their materials, by the elaboration or decoration of a simpler, more ordinary form, or by the very type or form of the object itself. Objects made from expensive or rare materials that are highly prized, such as gold in Ghana, copper in central Africa, or ivory throughout the continent, are traditionally associated with wealth or position. Intricately woven textiles popularly known as kente that include silk (plate 8.7) are more valuable than those woven only from cotton, but because of the complexity of this type of cloth, even a cotton kente is more expensive than most other textiles. It is important to note that prestige is not always equated with economic wealth. For instance, traditionally in Maasai society, only a married woman would wear a coiled metal ornament such as the one in the lower left corner of figure 8.1.

An important subgroup of prestige arts consists of objects associated with political leadership: many African art forms proclaim, aggrandize, and enhance the capacities of traditional rulers. The Asante in Ghana provide excellent examples. In addition to the Golden Stool (figure 8.2), which is believed to embody the soul of the Asante confederacy and the right of the asantehene (king) to lead it, Asante royal arts today include spectacular arrays of regalia including swords decorated with gold and gold-leaf-embellished staffs that include images associated with proverbs and stories that become royal messages. When notables gather, cloth umbrellas with gold finials protect them from the sun while adding to the visual display. Some state officials wear gold disk pendants that symbolize the purification of the king’s soul, while the king himself wears gold jewelry, gold-covered sandals, and kente (plate 8.7), cloth that in earlier times was the prerogative of royalty and that remains associated with political leadership, though now it can be worn by anyone who can afford it. All of this splendor asserts that Asante leaders possess the social, economic, and spiritual clout needed to run their state.

Figure 8.2. The Golden Stool of Asante with its bells, and behind it the stool carriers and guards. 1935.

Basel Mission Archives/Basel Mission Holdings QD-30.004.0002.

Popular art is a category that invites debate everywhere, and especially in Africa. It invokes a number of significant issues involving social geography, world history, and artistic training. In fact, its application to African creative expression pulls several scholarly problems into sharp relief.

The category is frequently characterized as restricted to Africa’s larger urban centers, with a very brief history that began during the colonial period as a response to the tremendous and fast-paced changes, social, economic, political, and spiritual, that accompanied a newly amplified and highly aggressive Western presence. These changes are understood to have produced an onslaught of new kinds of art, generally grounded in a syncretism combining African and European expressive traditions. This emphasis on change, urbanism, and outside influence is often used to distinguish popular from traditional art, which encourages a basic misunderstanding of the latter.

Many kinds of visual expression can be categorized as popular art. Included are painted signs and decorated walls for businesses, such as restaurants, barber shops, ice cream parlors, and photography shops; bus, taxicab, and truck embellishments in paint and other materials; genre and topical paintings on canvas, hardboard, and various other materials; cartoons, often of a strong sociopolitical bent; cement funerary portrait sculpture; elaborately constructed and painted wooden coffins; wall and table displays of imported enamel crockery; new types of cloth and fashionable clothing ensembles, including the spectacular factory cloth produced all across the continent; and posters announcing events such as movies, political rallies, and health campaigns. Some scholars also include wire and tin toys made by children in this category as well as similar toys made by adults to sell to tourists, and sometimes other forms of tourist art. This fluid and ever-changing cacophony of artistic expression finds parallel zones of creativity in music, dance and masquerade, theater, cinema, radio, television, websites, and blogs.

It is easy to see differences between the masks, figures, textiles, and ceramics we have discussed as traditional art and objects generally called popular art. These differences have inspired many observers to characterize the popular arts as largely urban, innovative, and modern responses to colonial and postcolonial life, and “unofficial” in the sense that they are described as not linked to the official ideology of a society or to its well-established traditions of expression. Such assessments are helpful but also simplifications, because many qualities are shared by popular and traditional art. In fact, it is difficult to fit some artworks into either of these categories.

Painted architectural embellishment is a good example. Scattered profusely across urban centers are wall paintings both abstract and figural, often designed to advertise businesses or to attract attention and generate enjoyment. Cartoon characters, spiritual beings such as Mami Wata (a water spirit usually taking the form of a mermaid or a snake charmer that is recognized across much of Africa), airplanes and other vehicles, or stylish abstract patterns are all part of the repertoire. Though it is fair to say that such artworks are more concentrated in urban landscapes, they are not restricted to them, as a zebra-striped restaurant and bar on a rural road northwest of Dar es Salaam indicates (plate 8.18).

A lavish and striking tradition of abstract house painting by women artists is widespread throughout towns in northern Ghana and Burkina Faso. Another can be found in South Africa, practiced by Ndebele women who indicate they developed their tradition from a much older practice by Sotho women that dates back at least five centuries. More recently, Ndebele women were encouraged by their government to create tourist-oriented villages featuring their painting.

In Mali, Dogon people employ a venerable tradition of rock wall painting that features abstract symbols and more figural images, both of which are used to pass information and discussion points from one generation to the next. Similar images, painted or carved in wood pillars that support public meeting areas, have become must-see stops on the trips many European and American tourists take to West Africa. Thus we see in just one kind of example a compromising of the idea that popular painting is urban, only as old as the colonial period, and not associated with official ideologies. We also see that African art designated as popular very often has a crossover relationship with the arts frequently labeled as tourist.

Though change has always been part of Africa’s social and visual expression, rapid change is a most salient characteristic of the popular arts. Very dramatic and swift social, economic, spiritual, and political change has been part of African history since the onslaught of colonialism, and part of global history since the industrial revolution. Expressive culture is deeply responsive to the constraints and opportunities contained in change, and so African artistic traditions have transformed and expanded substantially. The same can be said of Western art, which changed dramatically in the twentieth century, in large part from exposure to African and other non-Western artistry.

Thus we often have blurred boundaries between the categories scholars use for African art, which is evident when considering traditional and popular art. Both have been sparked by entrepreneurship, the will and capacity to be creative, innovative, sensitive to opportunity, and imaginative, while staying in touch with the realities of the world and utilizing experience and skill to shape that imagination convincingly. The arts attached to ritual may have changed more slowly than the arts devoted to public entertainment. And the arts viewed as traditional may express innovation in ways different from those viewed as popular. But entrepreneurship has helped shape both categories. Perhaps the most significant difference has been the accelerated rate of dramatic change that began in colonial times and fueled the arts we now call popular.

A great many men and women creating popular art receive no formal training, teaching themselves by experimenting with materials and techniques. As new expressive traditions develop and become popular, they attract more practitioners, who have the opportunity to learn from already established artists. Often these artists operate workshops where the younger members can gain experience and develop their reputations. Many then establish themselves on their own and even engage in some artistic rivalry with their former teachers and colleagues. As with most traditional art, we do not know the names of many of these artists, but increasingly artists are signing their work, especially in the case of popular painting.

Variety and creativity, frequently born of necessity, characterize the selection of many materials used to create popular arts. Artists have had to be extremely entrepreneurial on this score because supplies are often scarce and expensive.

Painting is perhaps the popular art best known around the world. It has many forms and sources of inspiration. For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, local consumers supported a tradition of genre, religious, and history painting, beginning in the 1950s. Many artists have participated, including such well-known painters as Cheri Samba and Tshibumba Kanda, and the audience for these artworks has expanded greatly to include people from all over the world. Colonialism and its violent aftermath, issues of ethics and spirituality, and often the personal experiences of the artists themselves are presented, along with village scenes, landscapes, and daily activities. In Tanzania, Tingatinga paintings (plate 8.19) have been popular in Dar es Salaam for nearly half a century. The tradition was begun by Eduardo Saidi Tingatinga, but many other artists have since created similar works, which cater especially to tourists and feature colorful, decorative scenes of flowers, animals, and people. Some artists, such as D. B. K. Msagula, paint much more personal visions, often creating vivid portrayals of contemporary social and spiritual ills, sometimes larger than the fit-in-your-suitcase size that characterizes most Tingatinga paintings. In Onitsha, Nigeria, where contemporary music, art, literature and theater combined to create a cauldron of intense creativity in the middle decades of the twentieth century, many painters created both signs and much more personal expressions. One painter, who used the name Middle Art (Augustin Okoye), assisted financially by the European scholar and supporter of Nigerian art Ulli Beier, portrayed the Biafran war. Blurred categories must be mentioned here, because many of these artists participate in contemporary art exhibits and are quite clearly part of the worldwide contemporary art scene.

While some paintings have fixed locations, others move over streets and roadways on buses, minivans, trucks, and cabs, often in combination with written proverbs and statements that cover a range of topics, from religious piety to the derring-do of Africa’s professional drivers and road crews. Frequently created by teams, the paintings can be abstract designs or images of famous musicians and movie stars. Sometimes, as in the case of the big buses of Nairobi called matatu (plate 8.20), the vehicles are completely rebuilt both inside and out and carry thunderous sound systems and highly theatrical driving crews. This is mobile painting, sculpture, and theater all at once.

Paints of all types are used: oils, acrylics, poster paints, and enamels, the last sometimes preferred because of their natural vibrancy. While Westerners consider canvas as the usual support for portable paintings, its high cost makes it prohibitive for much African popular art. Instead, artists paint on a variety of materials: various kinds of cloth, cardboard, plywood, particleboard, basketry, and glass all become surfaces for popular painting in Africa. In Ghana, flour sacks were used by painters creating posters to advertise films during the 1980s and 1990s (plate 8.21). Artists creating Tingatinga paintings usually use particleboard but may turn to cardboard or burlap if it is not available. During the 1980s, another group of Dar es Salaam painters called Nivada Sign and Arts became quite popular for painting flowers, fruit, and other objects on basketry.

In Senegal, glass painting has become very popular both locally and abroad. Islamic themes have been prevalent since its apparent inception in the late 1800s, but imagery also includes heroes and historical events, and the visualization of stories and proverbs. Here the question of categorization arises again: these fragile artworks are another example of blurred categories. Because some glass painters consider themselves in the fine arts category and the works are often for sale in fine arts galleries around the world, they can also be considered contemporary African art.

Imaginative and innovative uses of materials are even more evident in the creation of objects. A tradition of affordable jewelry in Timbuktu used gold-colored straw instead of metal and beads. Broad, flat winnowing baskets for sale in the Bamako markets are made of packing-strap plastic instead of fiber, while in South Africa colorful telephone-wire baskets of various shapes and sizes are sold in stores and exported abroad. A variety of objects ranging from oil lamps to tourist souvenirs are created from scrap, recycled, and repurposed materials, including metal cans, wire, and worn-out flip-flops.

Steamer trunks are a good example of popular object entrepreneurship. They are made from reclaimed and reworked metal drums and then painted with abstract patterns or depictions of figures such as the mermaid-like water spirit Mami Wata. These trunks enjoy much regional variation in embellishment and can be found as far afield as Mali, Niger, Cameroon, and Sudan. They are often given as gifts to newlyweds and are used all over for storage or even display. They enjoy a history that highlights the entrepreneurial character of much popular African art. Early in the twentieth century, steamer trunks imported from Europe were desirable but extremely expensive. Local innovators taught themselves how to make them at affordable prices, decorated them according to prevailing fashion, and created a land-office business for themselves offering what became a hugely popular item. Much smaller containers made by different artists, in the form of briefcases and purses, also use recycled materials. Some are created from bottle caps assembled on imaginatively constructed frameworks that allow the cases to be semi-transparent, producing a very pop-art feel (plate 8.22). Others are wood covered with flattened cans and replete with interior linings of newspaper comic strips.

Whatever the media, hues are frequently bold and compositions often aim for high contrast between juxtaposed colors, including black and white. Similar uses of color and contrast are seen in wire basketry from southern Africa and house painting from West Africa. They can also be found in textiles, some traditions of basketry, and even painted sculpture and body painting—another example of bridges between categories.

Popular painting styles and aesthetics are noteworthy. Some artists employ an almost cartoon-like technique, outlining figures and objects in black, stacking imagery on top of imagery, or creating checkerboard-style compositions of figures and objects over the whole surface of the work. Often there is no concern for any sense of perspective or three-dimensionality. Other artists create instead a sense of hyperrealism, especially in the heads and faces of people. Still other artists, such as Nigeria’s Middle Art, combine these two approaches, adding a lively interest to their works.

As with traditional arts, context is important to understanding the popular arts—it often sheds rich light on both innovation and continuity. Ghanaian fantasy coffins are a good example. They began with Ata Owoo, who gained local fame in the town of Teshi for designing an eagle-shaped conveyance in which a local chief could ride during processions. Around 1950, another chief commissioned a conveyance in the form of a cocoa pod, an important cash crop in the area and a significant source of wealth. He died before he could use it, however, so Ata Owoo’s workshop transformed the vehicle into a coffin, and the fantasy coffin tradition was born.

With Ata Owoo’s encouragement, Kane Kwei set up the first shop specializing in fantasy coffins, creating a variety of forms symbolizing success and status: for example, a mother hen for a woman who had successfully reared several children, a giant saw for a skillful carpenter, a Mercedes-Benz for a wealthy businessman, and boats, outboard motors, and various ocean creatures for people who earned a livelihood from the sea. By the time of his death in 1992, Kane Kwei’s coffins had been featured in museum exhibitions in Europe and North America, and today several of his former apprentices have their own shops, including his son, Ernest Anang Kwei, whose workshop designed and built the bright pink fish-shaped coffin illustrated here (plate 8.23). Honoring the deceased and celebrating their importance is important in Ghana, and included in more ancient times funerary terracotta figural sculpture. Funerary coffins, with their elaborate, appropriately imaginative shapes and wonderfully bold paint, become part of an elaborate funerary celebration that includes food, music, and dance, and a parade through town on the shoulders of mourners, giving the deceased a final opportunity to say good-bye to favorite places and people before burial.

Fantasy coffins, painted signs, and embellished vehicles impart information, stimulate the imagination, and draw attention to businesses while also amplifying the reputation of the artists, thereby enhancing the artists’ business too. This highlights the relationship of popular art to commerce. But it is really just an example of one of art’s principal functions, no matter what the category. When well done, art ought to stimulate and influence, and African artists say objects graced with effective adornment are more appealing to potential clients. It is worth noting that aesthetic considerations are often linked both to effectiveness in delivering memorable messages and to success in procuring clientele.

Two kinds of visual expression are particularly problematic to categorize: tourist art and toys. Workshops for creating tourist art exist all over Africa. Those in Côte d’Ivoire and Mali are especially known for reproducing traditional art forms—sometimes very beautifully—for shipment to large cities and eventual relocation in living rooms all over the world. Other workshops specialize in creating everything from napkin holders to lyrically styled ebony animals, along with masks and figures that eclectically combine elements from traditional art types all over the continent, often in the same object. It is fascinating to talk to the Western owners of these objects, many of whom are unshakable in their conviction that they possess authentic traditional art. Many middle-class and urban Africans also collect these objects, for a variety of reasons, making them popular at home as well as abroad. There are also beautiful traditions of basketry, some made of fiber, others of beautifully colored wire and even paper, that can be considered to belong to this category.

Toys can be a wonderful form of popular art made by and for kids, or a form of tourist art adults make to sell to foreigners. Airplanes, helicopters, and ground vehicles of all kinds are made of wire, cans, and other scrap materials. In some cases, these too are made in workshop contexts: in Dar es Salaam and nearby towns in 1985, for example, adolescents who possessed the passion, skill, and imagination to create these vehicles often formed their own toy-making workshops, exchanging materials and ideas and helping each other develop their own creativity. Their parents were impressed with and proud of their devotion and ingenuity. The creativity and dedication in this was brought home to us one evening in a Dar es Salaam parking lot when along came a boy pulling a toy truck, the cab of which was hitched to at least ten trailers, all in shiny metal, with lovely little wheels, well-designed axles, and a very long steering column running from inside the cab to the hands of this young entrepreneur. As he drove around the empty parking lot, he was beaming.

Vehicles are not the only things made by young people. In some of the same towns, boys created miniature furniture and decorative bird cages from millet stalks. Dolls are fashioned from wood, clay, cloth, gourds, and even basketry. While these items are not usually made for sale, other very similar objects are. In shops and roadside stands all over the continent there are what we might call toy reproductions—cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, airplanes, helicopters, dolls, and more—made by adults who know that Western visitors have become fascinated with African toys. However they are classified, these expressive objects are also worthy of attention.

The second half of the twentieth century saw an explosion of fine art (frequently also called contemporary art) on the continent, and by the end of that century African artists were being recognized by the international art world, with representation by foreign galleries, invitations to participate in events such as the prestigious Venice Biennale, and artworks made part of the permanent collections of major museums worldwide. In most respects, fine artists in Africa are like artists everywhere: they have had at least some formal training, they work in a variety of media and styles, and few are able to make their living solely from selling their art.

Many African fine artists today, like artists the world over, are trained in art schools and universities at home and abroad. During the colonial period, formal art programs and schools were incorporated into postsecondary institutions of higher learning in a number of countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, Sudan, and Uganda. For example, one of the most influential, the program at Makerere University in Uganda, became a magnet for art students from all over eastern Africa beginning in 1940. The Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts at Makerere University, named after the Englishwoman who spearheaded its formation, has remained a major center for the study of art, with a curriculum that has expanded from drawing, painting, and sculpture to incorporate graphic design and digital arts. Its graduates, who include Francis Nnaggenda (Ugandan, b. 1936), Sam Ntiro (Tanzanian, 1923–1993), Elimo Njau (Kenyan, b. Tanzania, 1932), and Teresa Musoke (Ugandan, b. 1942), not only have become educators and advocates for the arts but also have gained international recognition for their own sculpture and painting. Since independence, other important schools have also been created, including the Ecole des Arts du Sénégal (now the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts), which was established in Dakar by President Leopold Senghor in 1960.

Study abroad has enabled many fine artists to hone their skills, broaden their visions, and participate more easily in the global contemporary arts scene. Not surprisingly, their destinations are most often countries with which their homelands have special political or cultural relationships. Pioneering Senegalese artists Iba N’Diaye (1928–2008) and Papa Ibra Tall (b. 1935), the first instructors at the Ecole des Arts du Sénégal, both were trained in France, for example. During the postcolonial period, destinations also include countries that have developed aid and collaborative programs in Africa. During the 1960s, for instance, with the signing of a cultural cooperation and trade agreement with the Soviet Union by the newly independent Malian government, art students from Mali studied at the Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute.

Back on the continent, more informal instruction in the form of workshops, organized during colonialism and later, have also provided training. One of the best-known artists who followed that path is Twins Seven Seven (Nigerian, 1944–2011). An accomplished musician and dancer, he began attending workshops organized by Ulli Beier, a German editor and writer, and his wife, artist Georgina Beier, in Osogbo, Nigeria, in the 1960s. These workshops, part of the Beiers’ larger program of encouraging writers and visual artists and providing outlets for their work, stimulated Twins Seven Seven to try his hand at printmaking and painting; his depictions of the spiritual world and Yoruba folktales are characterized by a lively imagination and a distinctive style. The Anti-Ghost Bird (figure 8.3), an etching created during the 1960s, shows the energy and decorative use of line that characterize his work. More recently, in 1998, famed Nigerian printmaker Bruce Onobrakpeya (b. 1932), who has himself attended many workshops, including one in the 1960s at Osogbo, began the annual Harmattan Workshop, short courses in several media, all held during the same period and open to artists of all kinds and skill levels. Artist-organized workshops, frequently financed by outside corporate or nonprofit institutions, have become an important way for artists to interact with each other on both local and international levels.

Figure 8.3. Twins Seven Seven (Nigerian, 1944–2011). The Anti-Ghost Bird, 1960s. Etching on paper. H. 14 7/8 in.

Indiana University Art Museum, gift of Roy and Sophia Sieber. Photo by Kevin Montague.

Not all fine artists enroll in formal schooling or participate in workshops. Some learn how to work in their chosen media through apprenticeship or mentoring, much the same way that many traditional and popular artists do. The internationally recognized Malian photographer Malick Sidibé (b. 1936), for example, known for his images of Bamako youth culture during the 1960s and 1970s, learned his craft through an apprenticeship with a studio photographer. Likewise, Yoruba photographer Tijani Sitou (1932–1999) completed a three-year apprenticeship with a professional photographer in Gao, Mali, before opening his own studio in Mopti, a few hundred miles away, where for nearly thirty years he produced studio portraits that chronicle changing fashions in that city (figure 8.4). In addition, a few artists are self-taught, such as the Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez (b. 1948), whose colorful, fantastic models of buildings and cities have been featured in group and solo exhibitions in Europe and the United States.

While many African fine artists would enjoy the freedom to pursue art exclusively, most, like their counterparts throughout the world, whether university-educated or self-taught, are not able to make their living solely from their art. Many, though, find related employment as art teachers or administrators at schools and universities, as cultural officials, or in other professions that allow them to maintain connections with the art world even if they are not full-time artists. For example, Abdoulaye Konaté (Malian, b. 1953), whose work has been shown both in Africa and abroad (plate 8.24), is currently the director of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers Multimédia Balla Fasseké Kouyaté in Bamako.

The relative ease with which people travel today creates questions about exactly what makes someone an African artist. A number of students who leave Africa for study remain abroad, appreciating the greater ease with which they can be connected to the global art scene. In addition, of course, as increasing numbers of Africans in all walks of life emigrate or live abroad for extended periods of time for other reasons, their direct contact with the continent becomes limited to vacations or other short trips. The British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare (b. 1962), best known for his tableaus containing headless mannequins dressed in the kind of factory-printed cloth that has been popular in Africa for hundreds of years, is a good example of the increasingly common ambiguities associated with an “African” label. Born in London to Nigerian parents who had temporarily moved to England in pursuit of additional education, Shonibare and his family returned to Nigeria when he was three. He attended school in Lagos, but the family regularly vacationed in London, and at the age of sixteen he moved back there, first attending boarding school, then art school, where he earned an MFA in 1991. He currently makes London his home. Shonibare’s work explores issues of race, class, and African identity and has been shown in exhibitions and museums devoted to African art, but it has also been included in shows with no Africa connection, such as Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, which toured London and New York at the end of the twentieth century.

Figure 8.4. Tijani Adìgún Sitou (b. Nigeria, active in Mali, 1932–99). See My Henna [Regardez mon henne], 1983, printed 2006. Ink jet print. 12 by 12 in.

Indiana University Art Museum, gift of the Family of èlHadj Tijani Sitou, © The Family of èlHadj Tijani Sitou.

Artists living abroad in response to political conditions in their countries of birth also account for a small but significant number. For some of these artists, time living outside Africa may add up to more years than those spent on the continent. For example, Wosene Worke Kosrof (b. 1950) received a BFA from the School of Fine Arts in Addis Ababa in 1972 but left his native Ethiopia in 1978, responding to the repressive and violent situation that enveloped the country following the deposition of Emperor Haile Selassie in a 1974 coup. Earning an MFA from Howard University in 1980, he has remained in the United States, building an international reputation for paintings with elements based on the script used to write Amharic, the national language of Ethiopia.

The tremendous variety of materials, techniques, subject matter, and styles used today by artists the world over is also represented on the African continent. Certainly powerful and exciting fine art is being created in materials associated with traditional African arts, such as wood, cloth, and clay. South African Clive Sithole (b. 1971), for example, creates ceramics based on traditional Zulu forms, crossing long-standing gender divisions by working with clay, a medium traditionally associated with women. His Uphiso (2007, plate 8.25), for example, is based on a form used in the past to transport beer, but the raised images of three cattle circling the vessel and the beautifully mottled surface mark it as a contemporary interpretation.

Other artists have embraced materials and techniques that were brought from abroad, such as printmaking, oil painting on canvas, and photography. In addition, like artists worldwide, some African artists deemphasize the materials and techniques of classic fine arts, instead choosing forms such conceptual, performance, and installation art to express their ideas.

The use of manufactured and natural found materials to create art is worth special note. Though some artists may choose alternative materials because supplies such as oil paints and canvas are expensive and sometimes hard to come by, others purposefully choose to create art by salvaging and recycling used objects and materials. For the painter Kalidou Sy (Senegalese, 1948–2005), for example, the incorporation of found materials, such as the clay and metal fragments that are part of Ci Wara (plate 8.26) reflects his belief in the importance of artists interacting with their environments. Similarly, Maurice Mbíkayi (b. 1974), a Congolese-born artist who has lived in South Africa since 2004, created his 2010 Antisocial Network series by fashioning human skulls from computer keyboard keys and resin to raise questions about the relationship between humans and technology.

No matter what the materials, some African artists believe that the contents, or subjects, of their artworks should show direct connections to their African experiences. This idea was particularly promoted in the early 1960s, when most African nations became independent and when the Négritude movement was particularly strong. It is seen in works of artists such as Papa Ibra Tall of Senegal, who advocated subject matter that was readily identifiable as African in his own paintings as well as in those of his students at the Ecole des Arts du Sénégal. Elsewhere, similar notions are evident in the work of Groupe Bogolan Kasobané, a collective of six artists who began working together in 1978 after studying painting at Mali’s Institut National des Arts. They have rejected conventional canvas and commercial oil and acrylic paints, instead looking to locally available materials, particularly the hand-woven cotton and natural dyes used in making Bamana mud-dyed cloth. Unlike that cloth, which is traditionally patterned with nonfigural motifs that can be interpreted only by those familiar with the cloth, the creations of Groupe Bogolan Kasobané depict images that are widely accessible yet also related to West African life and culture.

Another Malian artist, Abdoulaye Konaté (b. 1953), also frequently draws on traditional arts in both subject matter and materials. The red ochre color of his 1994 wall-hanging textile Hommage aux Chasseurs du Mandé (Tribute to the Hunters of Mande, plate 8.24) and the small amulet-like additions attached to its surface are clear visual references to traditional Mande hunters’ shirts, which are frequently a similar color and covered with animal teeth and claws as well as leather packets containing prayers to ensure the hunter’s safety and success. While the large size of Konaté’s textile—it is over ten feet wide and more than five feet tall—would not allow anyone to mistake it for clothing, for those familiar with Mande culture its appearance not only instantly evokes hunters’ shirts but also calls to mind other aspects of Mande life such as the reddish earth of southern Mali, a rich cluster of ideas and practices associated with hunters and hunting (including special music and oral poetry), and spiritual beliefs and practices. In addition, more generally, Hommage aux Chasseurs du Mandé raises questions about the relationship between appearance and reality: while its attachments look like the amulets on the shirts that Mande hunters wear, do they have the same spiritual potency?

While Hommage aux Chasseurs du Mandé is clearly rooted in Konaté’s Mande heritage and speaks most effectively to those familiar with that culture, some of his other work addresses pan-African and global issues, and in this respect too the artist is typical of his colleagues on the continent. For example, his 2005 Gris-Gris pour Israël et la Palestine again refers to the power of amulets or “gris-gris” while, through depictions of the Israeli flag and the Palestinian-Arab head scarf, reflecting on the long-standing conflict in the Middle East that has captured the world’s attention.

Most African artists creating fine art have had a difficult time finding audiences and even venues for displaying their work. On the continent, the lack of well-developed gallery systems or other widely accepted means for making work available has made it challenging for artists to publicize, display, and sell their art. Furthermore, the small number of fine arts museums and galleries has meant that exhibitions routinely take place in embassy cultural centers, hotels, and other businesses unrelated to art, or in other impromptu display spaces.

Though beginning in the 1990s there has been a marked increase in the presence of contemporary African art in Western museums, exhibiting outside of Africa has also been challenging. While the major twentieth-century movements in European and American art had their roots in the work of artists who were inspired by traditional African art, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, through most of that century African art that showed clear affinities with those movements was frequently labeled as “derivative,” a pejorative designation in a sphere where originality is requisite for recognition. During the same period, other work was charged with being too African; frequently these figurative depictions of scenery and daily rural life were considered too parochial to command attention in major Western art centers. The reasons that contemporary African art received little praise—or even acknowledgment—go beyond the actual art, however, and include lingering colonial attitudes, racism, and the structure and business of the American and European museum and gallery systems.

Traditional, popular, and fine arts do not exist in isolation from one another. The popular arts, for example, often apply a population’s traditional ideas or activities to a new form of expression, frequently using new materials. Many contemporary artists who show their painting, photographs, sculpture, and mixed media creations in galleries all over the world, often quite divorced from their home communities, nevertheless present imagery that engages and explores the values and concepts their societies hold dear.

Whatever the form and whether visually complex or relatively simple, art is always composed of intricate layers of human imagination and social activity. However it is categorized, African art has as its base shared beliefs about the nature of the world and cosmos, whether those beliefs are shared within a region of the continent, as with most traditional art, or on a global scale.

While Islam, Christianity, colonialism, and participation in global economies and histories have certainly changed much African expressive culture, much traditional art persists, indeed flourishes. Much of it has been transformed by its creators and audiences into new forms, a process that has been going on in Africa for millennia. And much African art has proven profoundly influential elsewhere in the world. It was instrumental in the development of European modern art, and it has been part of the complex historical processes that produced African American folk art and the spiritual arts of numerous places, including Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, parts of Mexico, and parts of New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and a host of other Western cities.

Much of the art in all three categories presents a well-developed aesthetic acumen, produced by skilled and thoughtful artists. The range of forms, functions, and programs of symbolism across the continent is astounding, as is the highly innovative use of materials. These features alone make African art worth studying. But just as important for those who seek a rich understanding of the world and the place of people in it, or a broader understanding of the problems all human beings face and the variety of solutions they can use to solve them, the themes and situations the African arts address offer insights into humanity from which everyone can gain.

African Arts (Los Angeles). 1967–.

Barber, Karin. 1987. “Popular Arts in Africa.” African Studies Review 30, no. 3: 1–78.

Enwezor, Okwui, and Chika Okeke-Agulu. 2009. Contemporary African Art since 1980. Bologna, Italy: Damiani.

Grove Art Online. www.oxfordartonline.com/public/book/oao_gao.

Kasfir, Sidney Littlefield. 1999. Contemporary African Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

McNaughton, Patrick, and Diane Pelrine. 2012. “Art, Art History, and the Study of Africa.” In Oxford Bibliographies in African Studies, ed. Thomas Spear. New York: Oxford University Press.

Visonà, Monica Blackmun, Robin Poynor, and Herbert M. Cole. 2008. A History of Art in Africa. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Willett, Frank. 2002. African Art. 3rd ed. London: Thames and Hudson.