9 |

African Music Flows |

A man walked down the street in the busy Adjame marketplace in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, in West Africa. Amid the sounds of the street—honking horns, ringing cell phones, goat cries, people’s’ voices—he heard the latest hit song by reggae singer Tiken Jah Fakoly drifting toward him from a CD seller’s stall in the market. The song began with a distinctive slide guitar line, which was a sample from a 1990 recording by Geoffrey Oryema of Uganda in eastern Africa. Anchored by the repeating guitar line, the song developed as a twenty-one-string harp lute, the kora, entered along with a drum set and a keyboard. The man hesitated before the CD stand, taking in the song’s compelling groove or rhythmic pattern and contemplating the lyrics, which criticize the treatment of young girls in village contexts. Finally, an amplified call to prayer coursed out of loudspeakers, reminding him to continue on toward the mosque for the Friday prayer.

In this scene, ambient street noise was layered with sounds and instruments that reference other parts of Africa and the rest of the world. The reggae music reflected influences from Caribbean Jamaican music as well as African American jazz and rhythm and blues. The slide guitar also derived from African American music practice. But the performer on the slide guitar played music from an East African artist from Uganda. Then the kora, which is associated with West African music from the savanna area, was layered with the drum set and keyboard, reflecting influence from popular music of the West. Such layering of disparate kinds of music is typical of the genius in so many music performances in Africa.

Later that week, the same man, who is of Mau ethnicity—one of sixty ethnic groups in Ivory Coast—traveled several hundred kilometers by bus to his natal village in the west of the country to attend his father’s funeral. As is typical of a funeral of the Mau people, several musical ensembles played, including a percussion and vocal group that accompanied a masked dancer. Because this genre of mask and music originated among the Mau’s southern neighbors, the Dan ethnic group, the vocalists sang Dan songs in the Dan language to honor the Mau man’s life. At a key moment, the masked performer sang, “Ee, ge ya yi kan-bo,” “(The ge spirit has crossed the river).” This song indicated that the spirit ge had arrived from the world of the ancestors to bless those in attendance at the funeral. In response to the spirit’s call, singers responded, “Zere ya-ya.” The vocable response, without lexical meaning, nonetheless expressed great sentiment and connection: that the spirit’s call has been received. It also illustrated that musical events are frequently peopled not only by those individuals who ordinarily share time and space or contemporaries but by supernatural beings as well. These spirits may be ancestors who lived before and share neither time nor space ordinarily. But in a musical performance moment, time and space may be dissolved as ordinary people and spirits contact each other.

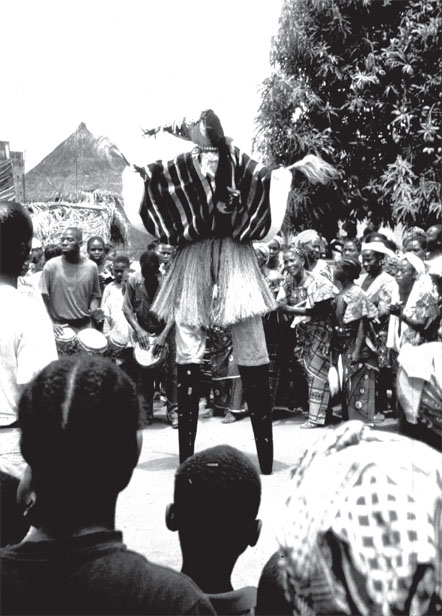

Figure 9.1. Performance of stilt mask spirit (gegblèèn), Dan people, Biélé, Côte d’Ivoire, 1997.

Daniel B. Reed.

Another instance of such contact with spirits in musical performance took place among Kpelle performers in Liberia when a man playing the gbegbetele, or multiple bow lute, called out to his tutelary spirit, the entity who he felt was responsible for making his performance really fine, “Eh Gbono-kpate we” (Eh, Gbono-kpate). Shortly he sang in a high-pitched voice, “Oo,” signaling that the tutelary spirit had arrived and was now present at the performance.

These examples not only illustrate the central importance of the spirit world mingling with the everyday world in musical performance in many parts of Africa. They also demonstrate a fundamental structural premise—a call, a response, an exchange that is central to understanding music performance as well as the ways that African musics have developed over time. In the cases above, the call-and-response took place between individuals communicating with each other in a musical event where they are for a time co-present.

Call-and-response is frequently multilayered in performance ensembles. A soloist sings a call and a chorus composed of many singers responds. A master drummer performs a call on his drum, and a dancer responds directly to his invitation. Simultaneously the supporting drums are responding to the master drummer’s call. So the call-and-response creates a complex web of relationships between singers and instrumentalists. Sometimes the call-and-response is so close and tight that a side-blown horn might play only one or two notes of the call and another horn may respond with one or two notes. A third and then fourth horn may enter, all fitting in between one another in a carefully calibrated pattern of call-and-response.

Musics in Africa have been characterized by movement and flow—of sound, people, and ideas across time and space. These aspects are clearly evident in the scenes above. Music flowed across boundaries between the worlds of the living and the ancestors along with spirits who are considered participants in music events. And the masked performers routinely borrowed traditions from neighboring ethnic groups, creatively reinterpreting these outside influences. The Mau man himself, like millions of others across the continent, regularly traveled back and forth between city and village, integrating cultural ideas and practice from urban and rural contexts. Meanwhile, like African American hip-hop artists, reggae musician Fakoly borrowed and recontextualized a musical motif—the catchy guitar line—originally created by another musician two thousand miles and nearly two decades removed.

Figure 9.2. Performance of transverse horn (turu) ensemble, Kpelle people, Baokwole, Bong country, Liberia.

Indiana University Liberian Collections. Photograph by Quasie T. Vincent.

Such reformatting of the music is considered both creative and clever and much to be admired. Extraordinary musicians draw upon a wide range of resources to fashion their music and draw from a wide range of materials—often unexpected to those looking for some kind of “pure” African music.

People, ideas, and goods flow throughout, in, and out of Africa, circulating around the globe. This chapter emphasizes an understanding of music within these flows. As if using a computer-based mapping system that allows the user to zoom in and out, the text will shift between viewing Africa from afar—taking in a broad view of geography and interactions linking various parts of the world—and from up close, looking at particular local musical practices. Whether considering broad historical trends or specific contemporary musical ideas and practices, in every case it is evident that music is central to the flow of African life. Music is not a frill but a vital part of human contact and interaction. As one Kpelle ritual specialist put it, if you’re upset, you make music to calm down. If you are happy and excited, you make music to arrive at the point of calm. Music becomes a centering point for people as they life their lives.

African peoples make and listen to musics that are intimately bound to the visual and dramatic arts as well as the larger fabric of daily life. Singing can hardly be conceived without dancing. Instrumental playing gives voice to a material object that is an extension of a person. Singers often enact or dramatize what they are singing, particularly if it is a narrative story.

Performance permeates the life of African communities across the continent. Music, as many Africans view it, is not a thing of beauty to be admired in isolation. Rather it exists only as woven into the larger fabric that also combines games, dance, words, drama, and visual art. As A. M. Ipoku, director of the Ghana Dance Ensemble, noted to ethnomusicologist Barbara Hampton, dance and music should be so closely connected that one “can see the music and hear the dance.” Or as a chief in Cameroon expressed to art historian Robert Farris Thompson, “The dancer must listen to the drum. When he is really listening, he creates within himself an echo of the drum, then he has started really to dance” (Thompson 1974). And the words that mean “performance” or “event,” whether the pele of the Kpelle or lipa-pali of the Basotho, are applied not only to music making, dancing, and speaking but also to children’s games and sports. Thus, singing and dancing mingle with theater and game and sport, and they are all considered part of the fabric of performance. One sense mingles with another almost invisibly as the visual and auditory and kinesthetic interweave with one another.

In political campaigns singers promote candidates for political office. As Kofi Busia campaigned for the presidency of Ghana, a musical warning was piped from a roving van about the political activities of Kwame Nkrumah, a former leader of the country. Owusu Brempong recalls the song text: “Before it rains, the wind precedes. I told you but you did not listen. Before it rains, the wind precedes. I told you but you did not listen.”

Griots, professional praise and criticism singers, on many occasions conveyed messages for their rulers as they have since before the time of Sunjata (1230–1255), the first emperor of Mali.

Performers of domeisia, traditional narratives of the Mende people of Sierra Leone, fashioned words, song, and gesture for evening entertainment. Women improvised a comfortable call-and-response pattern as they bent over to hoe the soil for rice planting and sing the songs of work. Elsewhere, a “money bus” driver played a tape in his tape player and the lyrics of Bob Marley and the sounds of reggae rose as the assistant ran along the side of the bus. Gaining speed, he then hopped on board through the open door, jogging a dance to the ambient sound. The members of the East and Central African Apostolic Church of John Maranke invoked the presence of the Holy Spirit with songs. In all of these settings music has been integrated into life, and though diversity throughout Africa is apparent, some common elements penetrate the myriad of details.

A description of an event observed by John Chernoff in northern Ghana shows the interweaving of different media in a single occasion:

Dagomba funerals are spectacles. The final funeral of an important or well-loved man or woman can draw several thousand people as participants and spectators. Small-scale traders also come to do business, setting up their tables to sell cigarettes, coffee, tea, bread, fruits, and other commodities to the milling crowds. Spread out over a large area, all types of musical groups form their circles. In several large circles, relatives and friends dance to the music of dondons and gongons. The fiddlers are also there. After a session in the late afternoon, people rest and begin reassembling between nine and ten o’clock in the evening. By that time, several Simpa groups have already begun playing. Two or three Atikatika groups also arrive and find their positions, and by eleven o’clock the funeral is in full swing. After midnight more groups come to dance Baamaya or other special dances like Jera or Bila, though the latter are not common. Baamaya dancers dress outlandishly, with bells tied to their feet and waists, wearing headdresses and waving fans. The dance is wonderful and strenuous: while gongons, flutes, and a dondon play the rhythms of Baamaya, the dancers move around their circle, twisting their waists continuously until the funeral closes at dawn.

Some of these same dance genres are also performed in other contexts, such as that of the Ghana Dance Ensemble, which often presents a shortened version of Baamaya on concert stages. Thus, music from one context flows and inflects another context, moving from ritual observance to entertainment, all the while transforming but retaining a core of the original genre.

While the funeral performance described above took place in the 1970s, such traditions persist in the twenty-first century. Funerals became prime sites for political protest during periods of civil unrest. This was the case not only in South Africa during the apartheid era but also in Liberia’s civil war, which plagued the country from 1989 to 2003. At the funeral of James Gbarbea in 1989, a former cabinet minister and political leader, who had quarreled with dictator Samuel Doe, a Kpelle choir sang words that they could not speak without being thrown in jail. But in music they had relative immunity to sing:

Jesus is the big, big, zoe [ritual priest].

We all will go.

Doe will go.

Thus, political expression that was suppressed in everyday life found a place in ritual music events, particularly funerals, where people’s lives were being commemorated. The charged ideas that could not be spoken in public could be sung at funerals. People found considerable solace and community power in being able to express themselves on these musical occasions.

African indigenous religious practice often conceptually links music to other arts and ideas. In performances of Ge forest spirits among the Dan of Ivory Coast, all elements of the performance—the dancer’s mask and costume, dance steps, spoken word such as proverbs, drum rhythms, and song—are conceptually integrated and believed to be the manifestation of Ge. What others might hear as “music” is defined simply as the sonic aspect of the presence of spirit.

Figure 9.3. St. Peter’s Kpelle choir rattle (kee) players, Kpelle people, Monrovia, Montserrado county, Liberia.

Indiana University Liberian Collections. Photograph by Quasie T. Vincent.

As is the case for Dan Ge performance, music in Africa is often fundamentally tied to particular activities and/or groupings of people. Children perform specific music and dance for their communities at the completion of initiation to mark their passage into adulthood. Women sing songs to the rhythms they create in grinding grain with huge wooden mortars and pestles. In West Africa, Mande hunters, or donso, play a hunter’s harp lute (donso ngoni) and sing songs to encourage their brethren to overcome adversity in the pursuit of game animals. In each of these cases, music is inherent to activities and processes that are part of the flow of life in African communities. Music is so much more than a frivolous expression that can be added on as an extra entertainment. Rather, it is a critical part of the lifeblood of human interaction in African communities, communities that are often under the stress of war and other kinds of duress.

Figure 9.4. Performance of dance mask spirit (tankoege), Dan people, Grand Gbapleu, Côte d’Ivoire, 1997.

Daniel B. Reed.

Music also exists as a part of a larger world, a world in which people constantly exchange culture via mass media, mass communications, commerce, and increased human mobility. Africans hear music through radio, television, CDs, cassettes, and cellphones, and in urban internet cafés. They quite naturally incorporate these sounds into local music. It is not unusual to find indigenous drums playing with electric guitar and other instruments, amplified electronically, even as songs are sung in indigenous languages. African musics, in turn, are broadcast around the world via these same media. As increasing numbers of Africans immigrate to Europe and North America, they exchange music and other cultural ideas with their new communities, all the while remaining in almost daily contact with their homelands via cell phone and computer messages.

Zeye Tete, a well-known singer from West Africa, received funding from a nongovernmental organization to film a music video of vocal music and dance while she lived in a refugee camp in Côte d’Ivoire during the civil war in neighboring Liberia. She organized some of the young girls in the camp to be a chorus of singers and dancers and accompany her solos as she created a visual as well as sonic spectacle within the camp. When she immigrated to Philadelphia several years later, that video circulated back and forth across the Atlantic among Liberians on the African continent and Liberians residing in the United States, documenting in music the pain of the war as they lived without a home, awaiting the peace and a resolution to their trauma.

Figure 9.5. Slit-log (keleng) ensemble, Kpelle people, Sanoyea, Bong county, Liberia.

Indiana University Liberian Collections. Photograph by Quasie T. Vincent.

Although one cannot deny the dramatic increases in intercultural exchange occurring in the globalized world of the twenty-first century, cultural exchange is nothing new to Africa. In musical and cultural terms, Africa can be understood as a continent, but viewing Africa as a separate space in isolation from its surrounding geographical context paints at best a partial picture. North Africa, for example, is as much a part of the Mediterranean region as it is a part of the African continent, and the horn of Africa is separated from the Arabian Peninsula only by the extremely narrow Red Sea. These geographical realities present themselves clearly in musical instruments, genres of music, ideas about music, and musical aesthetics that are to greater or lesser extents shared across continental boundaries.

How has this happened? In contrast to stereotypes of Africa, precolonial African history was characterized less by peoples living in great isolation and more by a great deal of cultural interchange. Of the many forms of cultural interaction in African history, none has been more important than trade. Trade routes crisscrossed the Sahara, linking sub-Saharan Africa with the Maghreb and points beyond, including Europe and the Middle East. When people exchange goods, they exchange other cultural elements as well, including musical instruments and aesthetics. Pilgrimage has proven to be another prominent promoter of cultural exchange. Muslims from all over Africa traveled north through the Sahara Desert to reach Mecca and Medina, the holy cities in Arabia where they carried out religious rituals that became high points of their lives. As pilgrims from Africa traveled to Arabia, they brought with them musical practices and instruments, which they shared with people along the way. In a reverse way, traders and others from Arabia and northern Africa brought musical instruments and practices to other parts of Africa. The large number of string instruments in the Sahel and Western Sudan regions of West Africa is likely due to that region’s long-standing interactions with North Africa, primarily through trade and the spread of Islam. One-stringed fiddles (e.g., Hausa gorge or Dagbamba gondze) almost certainly were introduced to Sudanic West Africa via contact with Arabic North African traders, educators, and proselytizers of Islam. In such circumstances of cultural exchange, goods and ideas flowed both ways. The three-stringed bass lute (hajhuj), played by Moroccans in gnawa spirit possession ceremonies, arrived from the south with slaves brought from West Africa. In the same way, drums from West Africa can be heard playing at night in some towns of western Arabia. Pilgrims left some of these instruments or even settled there permanently, changing the musical landscape of the places they traveled. In the late twentieth century, the jembe drum was introduced to Europe and North America primarily by touring African national ensembles, especially Guinea’s Les Ballets Africains. Originally from the Mande region near Guinea’s border with Mali, this drum eventually spread across the globe, from Japan to Canada to Germany becoming a ubiquitous symbol of Africa.

In other cases, scholars have found it can be difficult to determine the direction of the flow of influence. For instance, though plucked lutes (e.g., the Maninka koni, Fulbe hoddu, Wolof xalam, and Hausa gurumi) are played primarily by Muslim peoples in West Africa, these instruments’ points of origin have not been definitively proven. Scholars assume that among this same family of instruments can be found the antecedent of the American banjo—an instrument that was created by African Americans.

Even within sub-Saharan Africa itself, single instruments can tell the story of cultural flows and exchange. That the one-stringed fiddle mentioned above can be found in a belt stretching about two thousand miles, from Senegal to Lake Chad, indicates a history of interactions of groups in this region of the continent. Similarly, from the 1920s to the present day, Liberian Kru sailors traveled from port to port on the West African coast not only delivering goods but also spreading the guitar and the palm-wine guitar style.

Figure 9.6. Bamana musician Almamy Ba playing a four-stringed lute (bajuru ngoni) at his home, Bamako, Mali.

Daniel B.Reed.

While particular instruments allow us to trace African musical and cultural history, a general consideration of musical instrument types showcases the rich variety of music making in Africa. For Africans, instruments are humanlike, and the sounds of instruments are often considered “voices.” In West Africa, for example, different strings of a frame zither serve as different voices: that of the mother for a low-pitched string, and that of the child for a higher-pitched string. Two closely pitched strings may be called brother and sister strings. The Lugbara of Uganda name the five strings of the lyre with status terms for women. Shona musicians in Zimbabwe told ethnomusicologist Paul Berliner that they name the manuals of the mbira as “the old men’s voices” for the lowest register, “the young men’s voices” for the middle register, and “the women’s voices” for the highest register. They go further to describe individual keys: “mad person, put in a stable position, the lion, swaying of a person going into trance, to stir up, big drum, and mortar, with the names showing something about how the key works in the music.”

String instruments, with their subtle and often quiet “voices,” are often overshadowed in the popular consciousness by the great variety of drums in Africa. But string instruments abound on the continent as well. Perhaps best known is the kora, the harp lute that forms the personal extension of the West African griot, the itinerant praise-singer, historian, and social commentator of Mali, Senegal, and the Mande region in general. Equally important are the multiple bow lute, frame zither, musical bow, harp, lyre, and lute. The haunting sound of a whispered song of East Africa accompanied by the low, resonant, string-bass-like sounds of the trough zither is hard to forget.

If only drums are taken into account, there are goblet, hourglass, conical, barrel, cylindrical, and frame (tambourine) drums that range from handheld size to large enough to require a stand to support them or several men to carry them in procession. These instruments sound as “voices” of penetrating tone colors and distinct pitches, not simply rhythms. Their character is much more fully developed than is that of drums in the usual Western music conception. The entenga tuned drum ensembles of the kings in Uganda, the processional drums carried on horseback in northern Nigeria, the ritual drums laid horizontally on platforms in coastal West Africa, and the hourglass drum of West Africa that plays glides and slides of pitch as the player presses the thongs connecting the heads and tightening the skins with lightning velocity—all these are examples of African drums.

The mbira, or sansa, as it is known in other areas, with its plucked metal tongues, is a versatile instrument. It is often played at healing events for the Shona of Zimbabwe. In these rituals, musicians gradually build musical intensity and suspense. Finally a medium is chosen by the spirits and becomes possessed.

Rattles of all kinds, both containers and those with a bead network on the outside, join ensembles. Rattles are frequently attached to stringed instruments or drums to make the sound more complex and interesting aesthetically. These attached rattles, often metal discs, may come from found objects such as soft-drink bottle caps.

Clapperless bells struck with a stick are important, often setting the time line of the ensemble. Hollowed-out logs are slit “drums” played alone or in ensemble. The variety of struck, plucked, and shaken instruments stretches the imagination. And because sound is more important than appearance, a struck beer bottle will often replace a struck boat-shaped iron.

Many African peoples associate the sound of the blown instruments, such as flutes, whistles, and horns, with voices of spirits. The spirit of the Kpelle Poro secret society is realized through globe-shaped pottery whistles. Likewise, certain Dan ge spirits can manifest solely in sound produced by blowing through stone whistles and an earthenware pot.

Horns, which often appear in ensembles, are associated with the courts of kings and chiefs. They accompany the ruler and sometimes are played exclusively for his or her entourage. Horns come in many sizes and shapes and are made of wood, cow horn, ivory, or metal. In the Ashanti area of Ghana, local chiefs historically kept short horns, while paramount chiefs were permitted long trumpet ensembles. In more recent times, Africans have extended this historical practice by honoring nation-state leaders with these same ensembles. A Kpelle paramount chief in Liberia sent his ensemble of six ivory trumpets trimmed in leopard skin and his trumpeters for the 1976 inauguration of President William Tolbert, to honor the national leader. In 2012 President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia had a royal trumpeter assigned to her office who accompanied her on important occasions and signaled her arrival by blowing on a single side-blown ivory horn.

Figure 9.7. Young women dancers emerging from the Sande secret society, Kpelle people, Dige, Bong county, Liberia, 2009.

Indiana University Liberian Collections. Photograph by Quasie T. Vincent.

The Babenzele of the forest region of Central Africa play a breathy-sounding flute that leaps from low to high register and back again. The flute players alternate from flute to voice and back to flute. The singing tone is scarcely different to the ear from that of the flute, so similar is the sound they strive to achieve. Other peoples play flutes, singly or in groups. Some famous ensembles include the royal flute and drum players of the country of Benin.

Though instruments of a single kind, such as six side-blown horns or a group of xylophones, may play together in an ensemble, it is much more typical that ensembles consist of a variety of instruments, ranging from drums to horns to struck clapperless bells. Furthermore, these heterogeneous orchestras often perform with one or more singers and dancers in a complex ensemble with different types of participants.

Dancing is ubiquitous in many ensembles and considered a usual part of any performance. In some cases these dancers are specially trained and exhibit extraordinary skill in their movements. One of the places that special dance training takes place for Kpelle children is in the secret society, where they are provided with special instruction, particularly if they show aptitude. On some occasions dancers appear in masked form. On these occasions they represent aspects of the spiritual power and appear with wooden carvings and fabric covering the dancer’s face and head. Raffia or fabric may disguise the rest of the dancer’s body to complete the costume. In all cases the body movement to music is important and fits integrally with the instrumental and vocal music.

Indigenous musical instruments, along with aesthetic notions such as timbral preferences or tone colors and musical forms, flow through many types of music in Africa, from the traditional to the popular. As previously mentioned, popular music bands frequently combine local instruments with those of foreign origin. Nigerian fuji performers integrate indigenous hourglass pressure drums with lap steel guitars, electric guitars, keyboards and drum kits. Malian wassoulou songs, heavily rooted in local hunters’ music, feature a harp lute (kamale ngoni) derived from the hunter’s harp lute (donso ngoni). Additional strings and guitar-style tuning pegs are added to the kamale ngoni, which, along with acoustic guitar, violin, and iron rasp, accompanies songs sung by women in call-and-response style. In Zimbabwe, chimurenga musicians transfer melodic patterns from the mbira (plucked lamello-phone) onto the electric guitar, then add bass, drums, the mbira itself, and call-andresponse vocals to create a style that sounds like an electrified version of music from bira spirit possession rituals. These kinds of musical blends are facilitated by mass media and the constant movement of Africans back and forth between urban and village contexts.

Similarly, traditional musicians incorporate ideas and sounds from urban popular music styles into older forms. In Dan masked performances, master drummers quote rhythms from popular songs heard on radio and television in their drummed solos. When the dancing ge mask spirit matches the rhythms with ankle bells on his dancing feet, the crowd recognizes the rhythms and responds with shouts and hearty applause. In Senegal, Wolof sabar drummers create rhythmic passages (bàkk) inspired by everything from music seen on Japanese and American television programs to the sound of an electric fan.

Musical styles, and indeed even musicians themselves, flow back and forth between traditional performance contexts and performances on concert stages. In Ghana, Akom ritual practitioners perform in Akan villages, where performance spaces are formed by a crowd gathered in a circle in the village commons. Some of these same musicians will also perform Akom on stages in the capital city, Accra, often to honor the Ghanaian nation.

Just as indigenous musical instruments and ideas about music have flowed from local community contexts to concert stages, they have also made their way into Christian worship services. In many parts of Africa, early Christian missionaries stressed European-style four-part harmony to the exclusion of local musical practice. Over time, though, Africans began incorporating local instruments and even local aesthetics into church services. Every other Sunday at the Catholic church in Man, Ivory Coast, for example, a Dan chorus performs, using Dan drums and rattles and singing hymns in harmonies or parallel fourths in call-and-response manner, according to Dan custom. This pattern has been replicated in many places on the continent, as Africans, via music and dance, have crafted a form of Christian worship that more closely matches their cultural and ethnic identities than the music introduced by early missionaries. At the same time, these Christian churches have also incorporated African American religious musics. In Liberia, a typical Sunday service in a Lutheran church in Monrovia is often the occasion for the indigenous style of music from the Kpelle and Loma peoples as well as gospel songs, transplanted from the United States, and hymns from the hymnbook in four-harmony. The electronic organ is played alongside the electric guitar and the indigenous drums and gourd rattle.

At times, ideas flow through music in a covert way. In the Zimbabwean war for independence, which, like the musical style mentioned above, was called the chimurenga (literally, “struggle”), musicians recorded songs using metaphors in the indigenous Shona language that communicated coded messages to freedom fighters. Colonial administrators would not understand the lyrics until the chimurenga songs were broadcast over the radio and the message had already been communicated. Similarly, chimurenga artists used Shona proverbs as song texts to criticize colonial rulers:

Chiri mumusakasaka |

He who is (hiding) in a grass shelter |

Chinozinzwira |

gets a firsthand taste of discomfort |

Since the rulers were not mentioned by name, and interpretation of the proverbs required a certain level of cultural knowledge that the rulers generally lacked, the songs’ meanings were lost on them, but they were clearly communicated to Shona audiences. Meanwhile, in rural gatherings, villagers drummed, danced, and sang to raise the spirits of visiting soldiers. Multiple kinds of music were thus used as resources for the ultimately successful struggle against the colonial powers, and the sounds and texts of these styles became associated with the struggle itself.

In this case, serious messages and protest were conveyed in what was on the surface entertainment music. Like the choir in Liberia who performed at a funeral shortly before the civil war, musicians in Zimbabwe carried out political struggles through music.

Sound in Africa is everywhere noticed, admired, and shaped. Bus drivers take pride in horns that play tunes. Postal workers in Ghana cancel stamps in a deliberate rhythm that not only accomplishes the task at hand but entertains the workers as they interlock their rhythms. In African musics, sound imitates many things—the sounds of nature, of birds, of spirits. Virtually everything is subject to portrayal in sound and all of these voices combine in music events.

Sound becomes a medium for other senses as well. Consider the plight of the woman in this text of a song recorded by Ruth M. Stone in Liberia:

Our fellow young women, I raised my eyes to the sky, I lowered them. My tears fell gata-gata like corn from an old corn farm.

Gata-gata imitates not only the audible dropping of the corn kernels but the visual glimpsing of the tears rolling down the woman’s face and falling to the ground in full drops. On other occasions singers depict visual beauty. They sing about the smooth, shiny blackness of a well-carved bowl with a thin exterior wall that the hero’s wife carves in a Kpelle epic. Or a singer tries to show a little boy running very fast by imitating the sound of his running: ki-li-ki-li-ki-li.

Timbre, or tone color, the shading of sound that makes a trumpet sound different from a flute, a metal gong from a drum, matters a great deal to many Africans. English-speakers, however, lack the basic vocabulary to describe timbre, and Western staff notation only crudely indicates anything about it. In the 1930s ethnomusicologist George Herzog made some early cylinder phonograph recordings and discovered that among the Jabo of southeastern Liberia musical sounds are conceived as “large” or “small”; the large sounds are found in the lower register of pitches, and the small sounds are found in the upper register. The Kpelle of central Liberia talk about sound in similar ways. But when they refer to large voices and small voices, they are commenting not only about pitch but about tone color as well. They think of a large voice as resonant and hollow, “voice swallowed,” while a small voice is more penetrating and less resonant, “voice coming out.” Dan drummers distinguish gbin sounds from those that are kpè. Gbin sounds are lower in pitch but also “heavier,” referring to timbral density. To create a more gbin sound, a drummer will add a buzzing metal resonator to his instrument and then strike the drum’s head in such a way to bring out the lowest frequencies and darker tones. Kpè sounds, by contrast, are considered “dry,” and are achieved by striking the drum head near its edge to emphasize a less resonant timbre and higher pitch.

People in Africa highly value musical “voices” in interaction, and as a result often think of performance in a transactional sense. Like two people pulling at either end of a tug-of-war rope, rather than two people simply standing alone, one part rarely exists without the other. To understand one part is to do so only by seeing how it balances with another. Two xylophone players in southeast Africa sit opposite each other and share the same instrument. One has the responsibility of starting the performance; the other responds. One player fits his notes in between the notes of the other player. Similarly, an mbira player of Zimbabwe designates one part he plays as kushaura (to lead the piece) and the other part as kutsinhira (to exchange parts of a song). Africans extend this same transactional tendency to popular music instrumentation as well. Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat bands would feature multiple guitar lines that seemed to converse with each other throughout his lengthy songs.

In a different sense, the prevalent call-and-response form of African music is transactional. A soloist gives the call and the chorus replies. Though the parts may overlap and form a neat dovetail so that no space between the two is obvious, the solo holds license to vary while the chorus gives never-changing support. In this way the Kpelle speak of the singer “raising the song” and the chorus “agreeing underneath the song.” An hourglass drummer has problems playing his part alone, even though the beats of his part cross with the second drum. The drummer complains that he cannot “hear” his part without the second drum playing, expressing the idea that drums converse much as singers do.

Performers take the notion of transaction beyond the call-and-response, for they delight in segmentation and fragmentation within a performance from which they later create a profound togetherness. While in call-and-response one part performs a phrase of music and the other part answers with another phrase of music, in hocket a number of musicians each play one or two notes that all combine to make a single melody. Each part is much shorter and the fit is much tighter than in ordinary calland-response. The Kpelle horn ensembles mentioned earlier, groups that traditionally are attached to the chiefs, delight in this idea. Six horns combine their brief motifs to make a unit of music. The Kpelle hocket vocally in bush-clearing songs, where the voices interlock with great precision even as the slit drums are being played in the background. The Shona of Zimbabwe interlock panpipe sounds with voice and syllables and add leg- and hand-rattle accompaniment. Indeed, the hocket, in which performers depend upon split-second coordination, is one of the most highly valued music forms in Africa. A song might begin quite simply, but as the performance progresses, the performers add layer upon layer of segments and fragments with voices, instruments, and rattles. They all fit together in a complex of sound and movement and create a living, vibrating event of considerable beauty.

Call-and-response is just one of many aesthetic practices that has circulated widely as African peoples and their musics have spread globally. Africa can be understood to be a part of a trans-Atlantic region in which peoples of African descent live in great numbers, from South America to the Caribbean to North America and Europe. Africa can also be understood as part of a trans–Indian Ocean region, including Arabia, India, and other parts of Asia, where Africans now live.

A cycle of cultural and musical exchange between Africa and the Americas began with the horrific dispersal of African peoples throughout the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade, which lasted from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Another cycle of cultural and musical exchange took place between African and Arabia as another era of slave trade brought Africans from the eastern, central, and southern African regions to Arabia and the Indian subcontinent. African peoples in the Americas blended African and European musical ideas to create new musics such as jazz, African American gospel, and Afro-Cuban rumba.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, these sounds from the African diaspora began cycling back to Africa via radio broadcasts and the nascent 78 rpm record industry. These new sounds in turn influenced Africans to create yet more new styles. For instance, in the mid-twentieth century Congolese musicians adapted Afro-Cuban rumba to create soukous, whose infectious percussion, rhythm guitar arpeggios, and flowing lead guitar melodies spread across the continent to become one of the most influential African popular music styles of the twentieth century.

This cycle of exchange continues today through the spread of new musical forms via the mass media and increased travel between Africa and the Americas. Rap and hip-hop have taken the African continent by storm; it is mostly young Africans who use this new form, often to comment on social problems such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic. According to Alex Perullo, popular Tanzanian rapper Mwanafalsafa scored a major hit in 2002 with a song whose Swahili title translates as “He Died of AIDS,” in which the song’s protagonist preaches safe sex to his friends, only to himself perish from the disease because of not following his own advice. Rap competitions are common in nightclubs in cities around the continent. At one such bar in Blantyre, Malawi, scholars Lisa Gilman and John Fenn observed DJs warming up the crowd for a rap competition by spinning songs from across the diaspora, including Malawian hits, Congolese soukous, South African kwaito, and American rap and rhythm and blues.

Figure 9.8. Tiken Jah Fakoly performs for an educational benefit in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, on April 25, 2009.

Getty Images.

Reggae, first created by Jamaicans of African descent in the 1960s, remains a popular form in Africa. Like reggae pioneer Bob Marley, contemporary reggae stars Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly of Ivory Coast use reggae to express political dissent and call for social change. In 2001, Fakoly’s song “Promesses de Caméléon” (Promises of the Chameleon) was so effective in criticizing coup leader Robert Guei that Fakoly was forced to flee the country and lived for years in exile.

Many popular musicians combine influences from across the diaspora in single songs. Angelique Kidjo’s powerful song “Welcome” begins with a field recording of Muslim women in the north of her native Benin. After a verse sung in her native Fon language, Kidjo leads an African American gospel-style chorus singing (in English, though Benin is a French-speaking nation) the song’s refrain, “People say ‘welcome’ / People say ‘my house is your house.’ ” South Africa’s Soweto Gospel Choir combines southern African vocal traditions—themselves influenced by European missionary church harmony—with African American gospel styles to create a distinctive, rousing sound. Much African popular music can today be best understood as transnational music that results from the centuries-old flow of culture around the Atlantic, a flow that has only accelerated in recent years.

The cycle of exchange with the Americas is but one of many cultural flows impacting musics in Africa. Equally influential is the history of cultural exchange with the Arab world. As was the case with the history of interaction between Europe and Africa interaction, Arab interactions with Africa included conquest, religious proselytizing, and trade, including the trafficking of slaves. The slave trade in the Indian Ocean brought East Africans to parts of the Arabian Peninsula such as Oman. Parts of the eastern coast of Africa and the island of Zanzibar were in fact, for centuries, part of the Sultanate of Oman. This cultural exchange has resulted in African-derived musical styles in Oman as well as centuries-old musical blends of Arabic and African musics on the Swahili coast. In Tanzania, large orchestras perform “classical” taarab, an Arabic-influenced genre of sung Swahili poetry, while smaller, amplified bands perform a popular genre derived from taarab for dancing crowds.

Again, trade and the spread of Islam were among the major factors linking the Arabian Peninsula, northern Africa, and Africa south of the Sahara. West Africa also bears a great deal of influence from the Arab world. In northern Nigeria, for example, Hausa states adopted titles and practices from the Muslim world for centuries. Royal musicians playing kettle-shaped drums accompany emirs on public appearances, and double-reed oboe players use circular breathing to create nonstop, highly ornamented melodic flows bearing much resemblance to melodic phrasings in northern Africa and the Middle East. Islamic communities in Africa often share certain core musical aesthetic preferences, such as melismatic singing styles in more nasalized tones, and highly ornamented melodies in monophonic styles. These shared preferences led Senegalese popular musician Youssou N’Dour to cross the continent and collaborate with an Egyptian orchestra in the creation of the hugely successful, Grammy-winning album Egypt. While this album exhibits the historical connections between the Arabian Peninsula and Africa, it is best understood as an inter-African cultural exchange rooted in shared history and a common religious tradition.

Musics on the African continent today flow through a dazzling variety of events, instruments, costumes, and forms. Though from all evidence African musics have always changed, some kinds have changed more rapidly than others as peoples have mingled their musics in interesting ways. The oral history of people of Gbeyilataa in Kpelle country (though not the present practice) indicates that the harp lute of the Mande griots was played by some court musicians. This is not surprising given the role of many Mande traders in the Kpelle area. The Beni dance and drill teams of East Africa played European brass band instruments, adapting Western music and creatively blending local elements. These groups, flourishing from the 1890s to the 1960s, were observed in 1945 by A. M. Jones, who described how they danced four abreast, in time with the music, parodying the British army officers with extravagant airs.

On a broader scale, a number of countries today support musical performance troupes that select local dances and songs and present them on a Western-type stage. The performance is adjusted to a theater audience. When the National Dance Troupe of Guinea performs in New York at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, included in one portion of the repertoire is a modified ceremony from the Poro secret society. In many ensembles, national culture is emphasized and local differences are minimized.

This was the case for the Kendeja troupe, which was developed in Liberia. Young children were selected to live in Monrovia from the age of six, seven, or eight and grew up in a dormitory together with young performers of different ethnic groups. While they shared songs they brought from their home villages, these were often adapted to suit the sensibilities of international audiences and the requirements of the stage.

These international audiences became accustomed to learning about Africa from these traveling musical groups, whether they performed in Libya, China, or New York. Peter Adegboyega Badejo’s opera Asa Ibile Yoruba (The Ways of the Land of the Yoruba) premiered in Schoenberg Hall on the campus of the University of California at Los Angeles before an enthusiastic Western audience.

At a local level, many schools in Africa have brought in performers to teach young children indigenous music—often with influences from other places in the context of a Western education. Zimbabwean schools are well known for their choirs or instrumental ensembles, and they compete in regional events as they exhibit their skills. At school graduations these troupes from all over Africa exhibit their skills at playing music that mingles both outside influences and local musical traditions. Thus the flow of the arts through African life continues.

In the end, the music of Africa should be conceived as something that flows not only in tight local communities but also much more broadly: to the Americas and back, to Asia and back, to Europe and back, and to Latin America and back. Such flows occur not just once in history but many times, in a continually circulating fashion. These musics are essential to the fabric of life, whether it be entertainment, a ritual such as a funeral, work, or war. The sounds of Africa represent vitality, a mosaic in motion, and a balance within everyday life. Whether struggling in war or battling HIV/AIDs, whether commemorating the birth of a child or the death of a great chief, whether clearing the bush for a rice field or planting the seed, whether relaxing after a day in the mines or socializing after laboring on the rubber plantation, music brings an essential glue to hold things together. Through these performances, people can reorder their feelings and live life with a sense of balance and renewed vigor.

Berliner, Paul. 1993 [1978]. The Soul of Mbira: Music and Traditions of the Shona People of Zimbabwe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brempong, Owusu. 1984. “Akan Highlife in Ghana: Songs of Cultural Transition.” Manuscript. Indiana University, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 1986.

Charry, Eric. 2000. Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chernoff, John M. 1979. African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gilman, Lisa, and John Fenn. 2006. “Dance, Gender, and Popular Music in Malawi: The Case of Rap and Ragga.” Popular Music 25(3): 369–81.

Hampton, Barbara L. 1984. “Music and Ritual Symbolism in the Ga Funeral.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 14: 75–105.

Jones, Arthur M. 1945. “African Music: The Mganda Dance.” African Studies 4, no. 4.

Perullo, Alex. 2011. Live from Dar es Salaam: Popular Music and Tanzania’s Music Economy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Pongweni, Alec J. C. 1997. “The Chimurenga Songs of the Zimbabwean War of Liberation.” In Readings in African Popular Culture, ed. Karin Barber. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Reed, Daniel B. 2003. Dan Ge Performance: Masks and Music in Contemporary Côte d’Ivoire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

———. 2012. “Promises of the Chameleon: Reggae Artist Tiken Jah Fakoly’s Intertextual Contestation of Power in Côte d’Ivoire.” In Hip Hop Africa and Other Stories of New African Music in a Globalized World, ed. Eric Charry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Stone, Ruth M. 1982 Let the Inside Be Sweet: The Interpretation of Music Event among the Kpelle of Liberia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tang, Patricia. 2007. Masters of the Sabar: Wolof Griot Percussionists of Senegal. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Thompson, Robert F. 1974. African Art in Motion: Icon and Act. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Fakoly, Tiken Jah. 2007. “Non à l’Excision.” L’Africain. Wrasse Records.

———. 2008 [2000]. “Promesses de Caméléon.” Le Caméléon. Barclay Records.

Kidjo, Angelique. 1996. “Welcome.” Fifa. Universal/Island Records.

N’Dour, Youssou. 2004. Egypt. Nonesuch Records.