10 |

Literature in Africa |

Truth depends not only on who listens but on who speaks.

—BIRAGO DIOP

When most Americans and Europeans use the expression “African literature,” they are referring to the poetry, plays, and novels written by Africans that reach Western and Northern shores. These have typically been written in English, French, and, increasingly, Portuguese. If one takes the long or broad view, however, these contemporary works of international standing are but one segment of a vast array of word arts in Africa, which have a long, complex, and varied history.

We have no record of the earliest oral traditions, but we know that verbal arts in Africa, oral and written, are ancient and long preceded the modern era, characterized by European colonialism and the introduction of European languages. African literature can be said to include Egyptian texts from the second and third millennia BCE; the sixth-century Latin-language texts of Augustine of Hippo; texts produced in Ge’ez, the ancient language of the region that has become Ethiopia, such as those of the Axumite period (fourth to seventh centuries); and Arabic-language texts, such as those of fourteenth-century North Africa, seventeenth-century Timbuktu in the western Sahel, and the nineteenth-century eastern coast of Africa. And alongside the widely known contemporary traditions in imported but now Africanized languages and forms, there is ongoing written and oral production in indigenous languages such as Amharic, Kiswahili, Pulaar, Yoruba, and Zulu. Moreover, many bards, storytellers, poets, and writers in these languages have embraced contemporary genres and new media. This vast contemporary production of African-language literature and “orature” (oral traditions) is largely unknown and ignored by those outside the continent. Inside Africa, these oral and more accessible popular texts may be the best-known and most-appreciated literary forms.

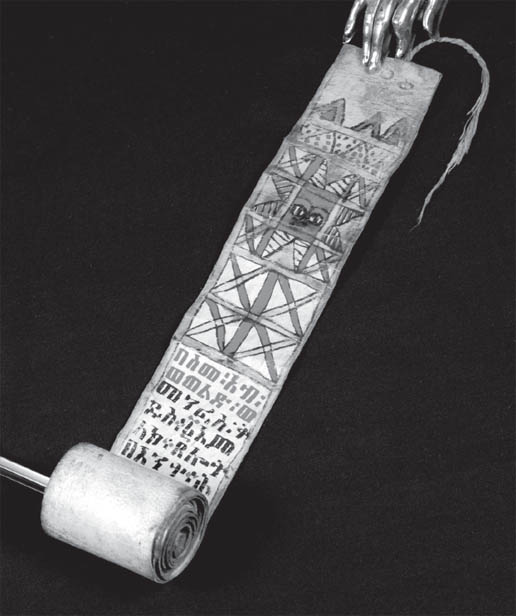

Figure 10.1. Vellum scroll in Ge’ez intended to ward off pain, suffering, or spirits. Undated, but probably early nineteenth century.

Lilly Library, Indiana University.

Europhone writers—those using European languages—draw on these indigenous oral and literary traditions as well as those of Europe, the Americas, and Asia, while African-language writers and practitioners of orature similarly dialogue with or reference Europhone writers and take up the broad range of issues that are of interest today across the world.

Africa is a vast continent, consisting of more than fifty nations and, by some estimates, more than two thousand languages and ethnic groups. Despite cultural similarities across the continent and a virtually ubiquitous history of imperialism and neocolonialism, there are many African experiences and many verbal expressions of them. Literature from across the continent has never been homogeneous or coherent. Moreover, to see in proper perspective what is most often referred to as African literature is also to recognize that it has been until recently a gendered body of work.

Figure 10.2. Fragment of nineteenth- or early twentieth-century copy of Dalā’il al-khayrāt, The Proofs of Good Deeds, a celebrated book of devotions for the Prophet Muhammad, composed in Arabic by the fifteenth-century North African Sufi saint al-Jazūlī and ornamented with Hausa, Mande, and Akan patterns and motifs.

Lilly Library, Indiana University.

Literary practice in Africa and understanding of it are continuously evolving. During the period of decolonization and formal declarations of independence around the continent in the mid-twentieth century, many literary texts portrayed the injustices and racism of the colonial period and the promise of independence. Beyond the 1960s, new “intra-African” themes of class, ethnicity, gender, and national identities emerged, thanks in part to the ever-increasing number of women writers, and there was greater awareness of written and oral production in mother tongues such as those mentioned above. There have also been new frameworks and vocabulary for studying cultural processes, which are themselves the subject of debate: postcolonialism, popular culture, performance, diaspora. Greater critical attention is being paid to the politics of local and international publishing and distribution and to multiple readerships in and beyond Africa. These developments have coincided with and have, in fact, helped produce a general shift in literary sensibility away from literature as pure art, a major paradigm for much of the twentieth century, to literature as text, an act between parties located within historical, socioeconomic, and other contexts. Of these developments, writing by women from around the continent has been especially important because it often challenges directly the meanings ascribed to the works of literary forefathers, bringing those works into sharper relief, forcing us to see their limits alongside their merits.

There are many ways to divide the terrain of literature written by Africans. These approaches reflect the fact that the continent is home to many different ethnic groups and cultural practices, political and physical geographies, local and nonlocal languages. Thus we routinely divide the literatures of Africa by region (West Africa, East Africa, North Africa, Central Africa, southern Africa, each of which is more or less distinctive environmentally and historically), by ethnicity (the Mande, for example, live across the region now divided by the states of Guinea, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Senegal), or by nationality (a heritage of nineteenth-century European literary practice, which privileges the force of national history and identity and whose merit in the African context has been debated for many years).

Literature produced in Africa is also often categorized by language of expression, such as Hausa, Lingala, Xhosa, “Lusophone,” “Anglophone,” “Francophone” (the last term being especially vexed) and, as elsewhere, by genre: poetry, proverb, epic, tale, short story, novel, drama, essay. (These terms have become a universal idiom for literary genres, even as they often obscure rich local classifications of literary and oral works.) The field has also been examined in terms of “generations” of writers, that is, cohorts defined by distinctive issues and styles anchored in specific historical realities—those writing in the period of decolonizaton (anticolonial, cultural nationalist writers), those writing in the postindependence era (postcolonial writers), and those writing increasingly from abroad (diasporic writers)—even though there is overlap in issues and their treatment across these so-called generations. These many approaches suggest not only the diversity and complexity of life on the African continent and in its diasporas but also the stuff of which literature is made: language, aesthetic and literary traditions, culture and history, sociopolitical reality.

This chapter focuses on major themes and trends of African texts that American undergraduates routinely encounter in their classes and then goes on to describe contemporary debates and developments in this field of study as well as challenges and prospects facing African writers and readers of African texts. Some reference will be made to orature and literature in mother tongues.

Literary production in Africa is vast and varied, but there are several impulses or currents in creative works of which we will make special note. The first is the reclaiming of voice and subjectivity, especially characteristic of Europhone writing in the colonial and early postindependence periods. Other themes to which we will devote attention include the critique of power, which has been the main feature of postindependence writing, and contestations of edenic representations of a precolonial African past. There is also an ever-growing awareness and exploration of hybrid African identities.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as nations around the continent moved to achieve decolonization, many Africans took up the pen. There had been African creative writers, essayists, and polemicists writing in African and European languages well before this time; in fact, the printing press arrived in Africa as early as the 1820s, and it was quickly put to use by African nationals for political and cultural purposes. As early as 1926, the Senegalese Bakary Diallo produced Force-Bonté (Great Goodness); and by 1929 the prolific writer Félix Couchoro of Togo published L’Esclave (The Slave); the South African Sol Plaatje published Mhudi in 1930; in 1931, Thomas Mofolo published Chaka, translated from Sesotho; the Senegalese Ousmane Socé brought out Karim in 1935; and Peter Abraham published Mine Boy in 1946. One remarkable work of fiction, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard, made a singular impression when it was published in London in 1952. Tutuola’s adventurous tale and hero are virtually lifted from the repertoire of Yoruba oral traditions and placed on the page in effective but non-”literary” English. The combination of rich imagination and untutored language gave the work a freshness and originality that garnered critical acclaim abroad and spawned great controversy among African writers and elites.

These works and others took up the issues of “national” history, of complex—and often conflicted—identities, and of modernity, issues that would still be critical twenty and thirty years later. But it was in the vast, concerted literary practice of mid-century that the moment of acceleration of contemporary African literature can be situated. This literature could justifiably be called “African” because it dealt with phenomena—race and racism, undoing alienation, reclaiming identity—whose reach could be felt throughout the continent. And there was by this point a wide audience for such texts, in Africa’s Atlantic diasporas, throughout Europe, and among African publics themselves.

In the era immediately preceding and following formal declarations of independence, Europhone narrative and poetry were born, for the most part, in protest against history and myths constructed in conjunction with the colonial enterprise. Writers struggled to correct Eurocentric images, to rewrite fictionally and poetically the history of precolonial and colonial Africa, and to affirm African perspectives. The implicit or explicit urge to challenge the premises of colonialism was often realized in autobiography or pseudo-autobiography, describing the journey that writers themselves had made, away from home to other shores and back again. African intellectuals and writers felt keenly that “truth,” as Senegalese Birago Diop had written in a neotraditional tale, depends also on who speaks.

In 1958, Chinua Achebe published Things Fall Apart, a novel that by century’s end would become the world’s most widely read work by an African. Characterized by a language rich in proverbs and images of agrarian life, this novel and Achebe’s later Arrow of God (1964) portray the complex, delicately balanced social ecology of Igbo village life as it confronts the newly arrived imperial power. Achebe’s protagonists are flawed but dignified men whose interactions with British emissaries are tragic and sometimes fatal. Like other writers of those years, Achebe wrote in response to denigrating mythologies and representations of Africans by nineteenth-and twentieth-century British and European writers such as Joyce Cary, James Conrad, Jules Verne, and Pierre Loti, to show, as Achebe put it, that the African past was not one long night of savagery before the coming of Europe.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s early trilogy of novels (Weep Not, Child, 1964; The River Between, 1965; and A Grain of Wheat, 1967), set in the days of the Emergency, Mau Mau, and the period immediately preceding Kenyan independence in 1963, explores the many facets of individual Kenyan lives within the context of colonialism: their experiences of education, excision, religious conflict, collective struggle, and the cost of resistance. Through the interrelated stories of its characters, A Grain of Wheat suggests, moreover, the coalescing of lives and forces in the making of historical events.

A decade later, Nigerian poet, playwright, novelist, and essayist Wole Soyinka aspired also to reclaim African subjectivity and agency. In Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), Soyinka represents the colonial factor as incidental, a mere catalyst in the metaphysical crisis of a flawed character, who is nonetheless the agent of his own destiny and of history. Elesin Oba, the horseman who must die in order to follow his deceased king to “the other side,” sees in the intervention of the British colonial authority a chance to stay his death and indulge his passion for life and love. Through every theatrical means—drum, chant, gesture, dance, as well as wordplay drawing on Yoruba poetic traditions—Soyinka suggests the majesty, social significance, and great personal cost and honor of Elesin’s task, and ultimately the magnitude of his failure.

A particular strain and manifestation of anticolonial poetry is the French-language tradition known as négritude. It was in Paris of the 1930s under the spell of surrealism, primitivism, and jazz that the idea of négritude arose. African and West Indian students, who were French colonial citizens and subjects, had come to the capital to complete their education. Products of colonial schools and assimilationist policies that sought to make them French, they had been taught to reject their African cultures of origin and to emulate the culture of the French. They had experienced an arguably deeper alienation than their counterparts schooled under British colonialism, with its more instrumental view of African cultures and languages. Now inspired by their African American brothers of the Harlem Renaissance and “New Negro” movement and the claims of German ethnographer Leo Frobenius and others, they felt the need to affirm those cultures from which they had been alienated, and they sought the means, both intellectual and literary, to rehabilitate African civilizations in Africa and the New World. The prime vehicles of this renewal were Jane and Paulette Nardal’s salon and journal, La Revue du monde noir. The poetry of négritude grew out of this nexus both to reaffirm “African values” and an African identity and, according to Léopold Sédar Senghor, to be open to the world.

In 1948, Senghor published the Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache (Anthology of New Black and Malagasy Poetry), in which he assembled work by French-speaking Caribbean and African poets, each of whom had “returned to the source,” composing poems out of the matrix of African culture. The tone and themes of négritude poetry vary from poet to poet. Birago Diop’s majestic “Souffles” (best translated perhaps as “Spirits”) seems to emanate self-assuredly from West African oral traditions and village culture, as it affirms traditional beliefs in the cyclical nature of life and in the ever-abiding presence of the ancestors. David Diop, at the other end of the spectrum, vehemently and passionately denounces slavery and colonial domination.

There are two Africas in many négritude poems: a utopian, pastoral Africa of precolonial times and a victimized, suffering Africa of colonialism. In both instances, Africa is often represented metaphorically as female, as in Senghor’s “Femme noire” (Black Woman) or David Diop’s “À une danseuse noire” (To a Black Dancer). Négritude poems may also juxtapose an Africa characterized by the communion of humans and nature with a deadened Europe of alienation and failed humanity, as in Senghor’s “Prayer to the Masks” (Prière aux masques), translated by Melvin Dixon (Léopold Sédar Senghor: The Collected Poetry, 1991):

Let us answer “present” at the rebirth of the World

As white flour cannot rise without the leaven.

Who else will teach rhythm to the world

Deadened by machines and cannons?

Who will sound the shout of joy at daybreak to wake orphans and the dead?

Tell me, who will bring back the memory of life

To the man of gutted hopes?

“Prayer to the Masks” thus emphasizes the complementarity of “Africa” and “Europe,” but in doing so it ironically lends credence to notions of their supposed essential difference, a difference that has often formed the basis of judgments of inferiority and superiority.

Another facet of the anticolonial tradition within French-language literature was its stress on the cultural dilemma of the assimilé or the contrast between two essentially different worlds. Camara Laye’s narrative of childhood in Guinea, L’enfant noir (The Dark Child), is another example. Written under difficult conditions, when Laye was an autoworker in France, the narrative nostalgically constructs home as an idyllic space in which the figure of the mother, nature, and the joys and virtues of village life are fused. Cheikh Hamidou Kane of Senegal, in a philosophical, semi-autobiographical narrative, L’aventure ambiguë (Ambiguous Adventure), adds to these contrasting paradigms of “Africa” and “the West” yet another layer of opposition: the spiritual transcendence of ascetic Islam and the numbing preoccupation with material well-being that are, for him, characteristic of Africa and the West, respectively.

Other writers of the period likewise wrote scathing fictions contrasting Africa and Europe. Cameroonians Ferdinand Oyono (Une vie de boy, 1956 [Houseboy, 1966]; Le vieux nègre et la médaille, 1956 [The Old Man and the Medal, 1969]) and Mongo Béti (Le Pauvre Christ de Bomba, 1956 [The Poor Christ of Bomba, 1971]; Mission terminée, 1957 [Mission to Kala, 1964]) provided the French-language tradition with its most satirical portraits of mediocre and hypocritical French colonizers. And Ugandan Okot p’Bitek, in a celebrated satiric poem, Song of Lawino (1966), translated from Acoli and modeled on songs of the oral tradition, uses the persona of a scorned wife to attack indiscriminate assimilation of Western ways.

However, not all anticolonial writers stressed such oppositions. Ousmane Sem-bene’s epic novel of the 1948 railway strike in then French West Africa, Les bouts de bois de Dieu (God’s Bits of Wood), is a powerful anticolonial fiction that moves beyond the opposition between static moments or sets of values (”tradition” and “modernity” or “good” authentic ways and “bad” alien ones). Sembene, a Marxist, conceives of change not as the tragic and fatal undoing of cultural identity but as a means of achieving a more just society, an inevitable process that is unquestionably difficult but transformative. In Sembene’s novel, the Bambara and Wolof abandon divisive definitions of identity based on ethnic group and caste and forge a larger and more powerful identification based on the common work they do. Under Sembene’s pen, urban work and technology are disentangled from debilitating ideologies of racial and ethnic identity, and the strike forces women and men to realize that the supposedly private and feminine sphere of the kitchen and the public, masculine, and political sphere of the railroad are inextricably bound in one and the same space of deprivation and injustice.

Still more violent struggles for liberation occurred in other countries around the continent that were home to white settlers. To the north, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria had also undergone the bitter experience of French colonialism. Algeria, France’s premier settler colony on the continent, had waged a protracted, horrific anticolonial war. Among the many notable French-language North African novels of this period are La grande maison (1952) by Algerian Mohammed Dib; Le passé simple (1954) by Moroccan Driss Chraïbi; and Nedjma (1956) by Algerian Kateb Yacine. Tunisian Albert Memmi also wrote a powerful essay denouncing the effects of colonialism, The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957). Questions of identity and culture have continued to generate incisive and powerful fictions, such as La mémoire tatouée (1971) and Amour bilingue (1983; Love in Two Languages) by Moroccan Abdelkebir Khatibi. The very history of French conquest in the nineteenth century and the Algerian war of resistance in the 1950s are likewise revisited and retold through the experiences of women in Assia Djebar’s L’amour la fantasia (1985) and Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement (2002).

Decades later, southern Africa was the scene of lengthy anticolonial struggles. Because of Angola’s long war of liberation, the condemnation of colonial domination and the determination to bear witness are intense and urgent in the Portuguese-language poetry of Agostinho Neto (Sagrada Esperanca, 1974 [Sacred Hope]) and the fiction of José Luandino Vieira (A Vida Verdadeira de Domingos Xavier, 1974 [The Real Life of Domingos Xavier, 1978, published first in French in 1971, when Vieira was incarcerated]).

Chenjerai Hove’s Bones (1988), winner of the 1989 Japanese-sponsored Noma Award, given each year to “the best book published in Africa,” and Shimmer Chinodya’s Harvest of Thorns (1989) were important literary testimonies to the chimurenga, the decade-long war of liberation in Zimbabwe.

Through the mid-1990s, protracted struggles against the brutal regime of apartheid in South Africa and its ripple effects across southern Africa were the impetus for a vast production of oral and written texts. In fact, South Africa has significant literary traditions in English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, and other languages, with English-language literature being written by white South Africans of British and Afrikaner descent and by black South Africans and those of mixed descent. Olive Schreiner’s Story of an African Farm (1883) is a remarkable novel, given its time, but liberal writing by white South Africans came to international attention in 1948 with Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. Prominent white South African writers of recent years include the prolific poet and novelist Breyten Breytenbach (True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist, 1984); novelist, playwright, and translator André Brink, best known in the West perhaps for A Dry White Season, 1979, and J. M. Coetzee, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003 and whose Life and Times of Michael K., 1983, and Disgrace, 1999, each won the Booker Prize.

South African Nadine Gordimer, the Nobel laureate of 1991, is also a writer of fiction. She too has published many novels and collections of short stories, including Burger’s Daughter (1979), July’s People (1981), A Sport of Nature (1987), My Son’s Story (1990), and Jump and Other Stories (1991). One of the unique strengths of Gordimer’s fiction is its sustained probing of racial and gender identities through incidents, objects, and her characters’ very own voices. In particular, she deconstructs whiteness and masculinity (and their opposites) as natural attributes.

Athol Fugard, the white South African playwright, has been a highly visible presence in New York theater circles for many years. Among his plays are Boesman and Lena (1969), still being performed in the United States as of this writing; Master Harold and the Boys (1982); and Sizwe Bansi Is Dead, co-authored with John Kani and Winston Ntshona (1976). Fugard’s plays are spare dramas of survivors, those who cope with lives entangled and nearly wasted in the snares of apartheid.

While liberal white South Africans, by and large, have expressed the guilt, fear, alienation, and general malaise of the white minority living under apartheid, black and black-identified South African writers have written of the deprivation, injustices, violence, and anger suffered by the black majority. Their narratives are often set in the cities and townships.

Among the earliest narratives of black life under apartheid are autobiographical novels set in urban South Africa, Mine Boy (1946) and Tell Freedom (1954) by Peter Abrahams, and Down Second Avenue (1959) by Ezekel Mphalele. The alienation of life in the slums of apartheid is also the subject of Alex LaGuma’s naturalist fictions A Walk in the Night (1967) and In the Fog of the Season’s End (1972). Mbulelo Mzamane’s Children of Soweto (1981) stresses the self-awareness, determination, and resilience of black South African youth in particular.

In the category of fiction, South Africans such as Richard Rive, James Matthews, and Miriam Tlali have made particular use and developed particular talents for the short story. In addition, many well-known novelists, including Alex LaGuma, Besssie Head, and Mbulelo Mzamane, have practiced this form of short fiction to special effect.

Yet poetry was a singularly important medium for black South Africans writing under apartheid. Oswald Mtshali’s Sounds of a Cowhide Drum (1971) and Fire-flames (1980), Sipho Sepamla’s Hurry Up to It! (1975), The Blues Is You in Me (1976), and The Soweto I Love (1977), and Mongane Wally Serote’s Yakhal’inkomo (1972) and No Baby Must Weep (1975) are all forged in the crucible of black urban life in South Africa—revealing not only the repression of township life but struggle, vibrancy, and humor. Of South African exiles residing in the United States, the poet Dennis Brutus, who had been imprisoned on Robben Island, was surely the best-known. Brutus’s poetry (Sirens, Knuckles and Boots, 1963; Stubborn Hope, 1978) is poised between an unrelenting naturalism, in which life in prison, in urban slums, or in exile has been narrowed, caged, trivialized, and demeaned, and a painful, tenacious desire for life as it might be, that space of imagination, possibility, energy, and renewal. Albie Sachs’s The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter (1991), a remarkable memoir of the personal costs of antiapartheid struggle, affirms, as does the poetry of Brutus, the belief in humanity that may inspire and grow in struggle.

It is worth noting in passing that memoirs of imprisonment are a veritable genre on the continent: Brutus’s Letters to Martha (1969); Rue du Retour (2003; originally published in French as Le chemin des ordalies) by Moroccan Abdellatif Laâbi; Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died (1971); Ngugi’s Detained (1981); and Egyptian Nawal el Saadawi’s Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1984).

Finally, with respect to South Africa, then, the tenor of literature has shifted since the 1990s, with the liberation of Nelson Mandela, who had been imprisoned for twenty-seven years, and the coming to power of the African National Congress in the first democratic South African elections. This shift will be taken up again below.

The critique of foreign domination under colonialism and the concomitant, urgent issue of identity are, as indicated above, often constructed as a conflict between the assimilation of “Western” ways and an African authenticity, and they are often articulated in realist narratives. With the advent of formal independence little by little throughout the continent, these issues gradually cede center stage to disillusionment and a critique of abusive power and corruption, such as Achebe unveils in his novels No Longer at Ease (1960) and Man of the People (1966).

The earliest fiction of Ghana’s premier novelist, Ayi Kwei Armah, The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968) is set in the last days of the Nkrumah regime. In this novel of disillusionment and alienation, a railway clerk, “the man,” makes his way in a greedy and corrupt world. In later novels, from Two Thousand Seasons (1973) and The Healers (1978) to Osiris Rising (1995), Armah’s fiction moves from the focus on the personal experience of disillusionment to historical and allegorical analyses of African failure to resist Arab and Western conquerors.

In recent works, the critique of postindependence regimes goes hand in hand with a change in literary form that Ngugi wa Thiong’o suggests in his provocative essay Decolonising the Mind (1986):

How does a writer, a novelist, shock his readers by telling them that these [heads of state who collaborate with imperialist powers] are neo-slaves when they themselves, the neo-slaves, are openly announcing the fact on the rooftops? How do you shock your readers by pointing out that these are mass murderers, looters, robbers, thieves, when they, the perpetrators of these anti-people crimes, are not even attempting to hide the fact? When in some cases they are actually and proudly celebrating their massacre of children, and the theft and robbery of the nation? How do you satirise their utterances and claims when their own words beat all fictional exaggerations?

Within the last decades of the twentieth century, as Africans grappled with the new abuses of neocolonial regimes and seemingly inexorable global processes, the literary landscape was strewn with quite stunning fictions of failure. Congolese writers Sony Labou Tansi (La vie et demie, 1979 [Life and a Half] and L’Etat honteux, 1981 [The Shameful State]) and Henri Lopès (Le Pleurer-Rire, 1982 [The Laughing Cry, 1987]) have given us compelling satires of dictatorship. Labou Tansi’s comic and nearly delirious fables and plays expose not only the corruption and savagery of such dictators but their pathetic frailty and insecurity. Ngugi’s fictions, Petals of Blood, Devil on the Cross, Matigari, and most recently Wizard of the Crow (2006), signal the greed for wealth and power unleashed by “independence” and the betrayal of Kenyan peasants and workers by leaders who collaborate with international capitalism when they do not vie with it. These fictions cross over into the absurd and turn away from the realism that characterizes many early texts focusing on the ills of colonialism. As Ngugi has suggested, writers invent forms commensurate to their perceptions and intuitions of new and troubling realities.

The négritude poets had defended the humanity of those whose humanity had been denied on the basis of “race,” a step that was unquestionably necessary. But what this meant often was an affirmation of an African or racial essence and the idealization of a time before colonialism that was knowable mostly through the interpretive lenses of anthropological, literary, and perhaps oral discourses. Traits that were held to be “naturally” African—such as love of nature, rhythm, spirituality—and that had been negatively valued were now seen as positive. These particular representations of African identity and a racial or pan-African nation came and continue to come under attack by African intellectuals and writers, most notably Wole Soyinka (Myth, Literature and the African World, 1976), Marcien Towa (Léopold Sédar Senghor: Négritude ou servitude?, 1971) and Stanislas Adotévi (Négritude et négrologues, 1972). Likewise, literary sequels to and revisions of this perspective now abound.

Yambo Ouologuem’s Bound to Violence (1968), set in Sahelian West Africa, is a chronicle of a fictional dynasty that is corrupt, barbarous, and politically astute—a fitting adversary, then, for the newly arrived French colonials. Ouologuem negates négritude’s claim of precolonial goodness and seems to assert instead an inherent African violence.

A still more important sequel to and revision of these early representations is the writing by women, which has developed rapidly since the 1980s. What was missing in the early chorus of voices denouncing the arrogance and violence of the various forms of colonialism, and what was in some cases ignored, were female voices. As recent writing by women makes clear, gender gives writing a particular cast. Anticolonial male writers critique the imperial and colonial project for its racism and oppression, but they nonetheless (and not unlike the European objects of their critique) portray these matters as they pertain to men, and they formulate a vision of independence or of utopias in which women are either “goddesses,” such as muses and idealized mothers, or mere helpmates. Women writers of that era and new writers, however, introduce matters of gender explicitly, as they nonetheless critique the underpinnings of the colonial project or its aftermath.

It is in this sense that Mariama Bâ’s 1981 epistolary novel So Long a Letter shook the literary landscape. At the death of her husband, Bâ’s heroine, Ramatoulaye, writes a “long letter” to her divorced friend Aïssatou, now residing with her sons in the United States. Through the experience of writing, Rama comes to terms with her own independence, having been betrayed by her husband of many years, who took as his second wife a friend of their teenage daughter.

If Ouologuem’s Bound to Violence had already questioned the premises of black nationalism and of a “pure” time before colonialism, Bâ’s novel made clear that the nationalism and independence that these now celebrated male writers had been defending were, by and large, patriarchal: women were symbols of the nation or, at best, helpers of man, who alone would reap the full fruits of independence. In Bâ’s novel, which is imbued with its own prejudices, we nonetheless see a conflation of class biases, male vanity, and female complicity in the practice of polygyny. In this novel and her posthumous Scarlet Song, which describes the stakes and constraints of interracial or, more precisely, cross-cultural marriage, one can infer the gender biases of these early notions of nation and identity.

As with the French-language literatures of Africa, a powerful force in English-language literature has been the emergence of women writers, who have filled what was a deep literary silence surrounding women’s lives. Flora Nwapa’s Efuru (1966) suggests the tension between women’s desires and the strictures of womanhood in the same era that Achebe and other male writers seemed to portray as the nearly golden age before colonialism. She concludes her novel with this haunting passage:

Efuru slept soundly that night. She dreamt of the woman of the lake, her beauty, her long hair and her riches. She had lived for ages at the bottom of the lake. She was as old as the lake itself. She was happy, she was wealthy. She was beautiful. She gave women beauty and wealth but she had no child. She had never experienced the joy of motherhood. Why then did the women worship her?

The passage above opens a path for Nwapa’s sister novelist from Nigeria, Buchi Emecheta, who has authored many novels. The most acclaimed of these may well be The Joys of Motherhood (1979), which examines marriage and the family in the village and colonial city from a woman’s perspective. Emecheta has now created her own publishing house in London, where she resides.

Ghanaian Ama Ata Aidoo, in her early collection of short stories and sketches No Sweetness Here (1971), gives voice to women’s concerns as they face problems of urbanization and Westernization: standards of beauty, the absence of husbands and fathers, prostitution, clashing values and expectations. In a play, Anowa (1970), remarkable for its time, Aidoo boldly explores the intersection of women’s oppression and transatlantic slavery. And in another novel of this early period, Our Sister Killjoy (1977), Aidoo stages an amorous encounter between two women, a Ghanaian and a German, in Berlin. In a more recent novel, Changes (1992), Aidoo examines the meaning of friendship, love, marriage, and family for young women of diverse religions, backgrounds, and cities in contemporary West Africa.

If for Sembene social transformation proceeds from the material world of the workplace and the kitchen, that is, from the outside in, for South African writer Bessie Head this transformation proceeds from the heart and spirit, from the inside out. Head, who has been of particular interest for Western feminists, sets her fictions in rural Botswana, where she lived in exile. When Rain Clouds Gather (1968), Maru (1971), A Question of Power (1974), Serowe: Village of the Rain-Wind (1981), and a collection of short stories, The Collector of Treasures (1977), lay bare the mystifications of race, gender, and a patriarchal God. A particularly moving scene from Rain Clouds exemplifies this transformation: titular authority and might give way to the moral force of ordinary people. The mean-spirited and reactionary rural Botswanan chief is disarmed by the sheer presence of the villagers who have come purposefully to sit in his yard and wait for him to emerge and face them. They make no threats of violence, but he knows they will no longer tolerate his excesses, that he is effectively divested of power.

Another avowed feminist, well known to Western readers, is Egyptian physician Nawal el Saadawi, who has been a staunch critic of oppressive political and religious regimes. She has written innumerable Arabic-language narratives such as Woman at Point Zero (1975) and The Fall of the Imam (1987).

Nervous Conditions (1988), an account by Zimbabwean Tsitsi Dangarembga, is the story of women’s resistance and resignation before the double bondage of settler colonialism and patriarchy. Le baobab fou (1982; The Abandoned Baobab) by Senegalese Ken Bugul is a rebellious young woman’s account of coming of age, of the journey from countryside to city. This fierce and ambiguous autobiographical narrative traces the heroine’s hellish road from her Senegalese village to Brussels, while Dangarembga’s young Tambu struggles against the racism of colonial Rhodesia, the deprivations of her class, and the male privilege of her brother, father, and uncle. Women who survive, who provide, who circumvent patriarchy are the heroines of this story. A new poetic language and feminist voice arrived on the scene in Yvonne Vera’s retelling of Zimbabwe’s colonial encounter and wars of liberation, Nehanda (1994) and Under the Tongue (1996), and her bold, passionate explorations of female desire, Butterfly Burning (2000) and Stone Virgins (2002).

The Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah (From a Crooked Rib, 1970; A Naked Needle, 1976; Sweet and Sour Milk, 1979; Sardines, 1981; Maps, 1986) also earned a reputation for a feminist stance: his female protagonists bring into sharp focus issues of gender and nationalism. Another searing contestation of the national project in this period comes from Dambudzo Marechera of Zimbabwe, whose collection of short fiction The House of Hunger (1978), winner of the 1979 Guardian Fiction Prize, recounts, in near verbal delirium, the brutalization and violence of life in a Zimbabwean township.

Many of the established writers have continued to write with new perspectives or in new ways. Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah (1987), for example, set in the city of Lagos, is a “dialogic” narrative, interweaving several perspectives and several registers of language, the voices of women and men of professional and popular classes.

Figure 10.3. Book signing by Yvonne Vera (Zimbabwe) and

Calixthe Beyala (Cameroon), Humboldt University, Berlin,

spring 2002. Eileen Julien.

Les Soleils des indépendences (1968; The Suns of Independence, 1981), the first novel by Ivorian Ahmadou Kourouma, was a momentous event in the French-language tradition because of its nearly creolized, Malinke-inflected French and its exploration of the relationship between masculinity and nation, as embodied in its protagonist, the noble Fama, dispossessed by colonialism and the ensuing independence. The rhythms of spoken language also characterize Kourouma’s later work, for example, Allah n’est pas obligé (1999; Allah Is Not Obliged, 2007), which has become a staple of a new genre, the child-soldier narrative.

Interesting use has been made of the detective or mystery story, or, more generally, of teleological endings, as in Ngugi’s Petals of Blood (1977) and Devil on the Cross, translated from the Gikuyu (1982); in Boubacar Boris Diop’s novels, from the earliest, Le Temps de Tamango (1981; The time of Tamango) to the more recent Murambi: Le livre des ossements (2000; Murambi: The Book of Bones, 2006); and in Sembene’s Le Dernier de l’empire (1981; The Last of the Empire, 1983) and Asse Gueye’s No Woman No Cry (1986). Some scholars have argued that teleological endings suggest the ability of the reading subject to reorder facts, to rewrite history and thereby create a sense of power to shape destiny. That interpretation would offer insight into the popularity of this genre in postindependence African nations. The increasing interest in this genre and other new forms suggests ever broadening and diverse experiences and perspectives. There has been an increase in narratives of war, of ethnic or civil violence, in which global forces, too, are at work: Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English (1986), the aforementioned Murambi and Allah n’est pas obligé (1999), Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier (2007), and Emmanuel Dongala’s Johnny chien méchant (2002; Johnny Mad Dog, 2007).

Following the Rwandan genocide of 1994, in which perhaps one million people were killed, a group of French-language writers—including Senegalese Boubacar Boris Diop (Murambi), Guinean Tierno Monénembo (L’aîné des orphelins, 2000 [The Oldest Orphan, 2004]), Ivorian Véronique Tadjo (L’ombre d’Imana: Voyages jusqu’au bout du Rwanda, 2000 [The Shadow of Imana: Travels in the Heart of Rwanda, 2002]), Abdourahmane Waberi (Moisson de crânes, 2000 [Harvest of skulls])—were invited for a several-month visit to Rwanda, after which they wrote novels to bear witness to what they had seen and learned about the massacre.

At the other end of the spectrum, the publishing house Nouvelles Editions Ivoiriennes has created the French-language romance series Adoras. Such “popular” fictions, like the many pamphlets from Nigeria’s Onitsha market, appeal especially to urban youth, students, and workers aspiring to modern, middle class lifestyles. Written in African and European languages, such fictions, it has been argued, often offer moral and practical advice (Stephanie Newell, Readings in African Popular Fiction, 2002).

Likewise, a “magical” or “animist” realist vein has developed in fiction by Africans, embodied most prominently in The Famished Road (1991) by Nigerian Ben Okri. This Booker Award–winning novel, the story of an abiku, a spirit child, born to poor Nigerian parents, can be thought of as a descendant of Tutuola’s narrative.

If we turn from narrative to performance and poetry, alongside Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, the most popular playwright and director in Nigeria may well be Femi Osofisan, author of more than fifty stage and television plays, including Esu and the Vagabond Minstrels (1975) and Morountodoun (1969), about a farmers’ uprising in western Nigeria and drawing on the myth of Moremi, the Ife queen who surrendered herself to an enemy camp in order to learn their secrets. Among other distinguished Nigerian writers are poet and playwright John Pepper Clark, who has also edited and transcribed the Ijaw epic The Ozidi Saga (1977); the syncretic modernist poet Christopher Okigbo (Labyrinths with Paths of Thunder, 1971); and neotraditional poet Niyi Osundare (The Eye of the Earth, 1986), winner of the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and the Noma Award.

Among Ghana’s well-known poets whose work is marked by Ewe oral traditions are Kofi Awoonor (This Earth, My Brother, 1971; Breast of the Earth, 1975) and Kofi Anyidoho (Earthchild, 1985; Ancestral Logic and Caribbean Blues, 1992). Malawi’s most renowned poet is Jack Mapanje (Of Chameleons and Gods, 1981; The Beasts of Nalunga, 2007). It is safe to assume, of course, that there are countless poets today writing and performing in every language on the continent. If, for example, we take only the case of contemporary Nigerian English-language poets, who are ever conscious of the enormous imbalances of power in Africa today, including the abuses of an endless chain of military and postindependence dictators, a short list might include Odia Ofeimun (The Poet Lied, 1989; Dreams at Work, 2000; Go Tell the Generals, 2008), Ogaga Ifowodo (Homeland and Other Poems, 1998; Madiba, 2003) Toyin Adewale (Naked Testimonies, 1995; and Twenty-Five Nigerian Poets, 2000, the latter an anthology co-edited with the African American Ishmael Reed), Uche Nduka (Flower Child, 1998; Bremen Poems, 1995; Chiaroscuro, 1997), and Tade Ipadeola (A Time of Signs, 2000).

Literary traditions in Kiswahili (or Swahili) are exemplary of African-language literatures. Swahili developed through many centuries of contact with Arabic-speaking inhabitants along Africa’s East Coast and has absorbed elements of Persian, German, Portuguese, English, and French. Today it is the mother tongue of approximately five million people, but thanks in part to German and British colonial governments, it is spoken by at least eighty million people from Tanzania and Kenya to Somalia in the north, the Comoros Islands to the east, and Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the interior.

As with virtually all oral and written African-language poetic traditions, dating and authorial attribution of historical Swahili poems is difficult. While the oldest existing manuscripts from the Swahili coast bear dates from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, scholars hypothesize much earlier origins for written Swahili verse. It is often unclear whether dates on manuscripts indicate the actual date of composition of a poem, the date of its performance and scripting, or the date of copying of a manuscript. Oral texts could have been written down decades or centuries after their first composition, and written texts could have been memorized and transmitted orally for equally long periods. It is likely that many Swahili poems circulated simultaneously in writing and by word of mouth. The boundary between oral and written modes has never been rigid, and both methods of composing and preserving poems persist still today.

In addition, although the majority of Swahili manuscripts that have survived from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries focus on themes and narratives taken straight from the Qur’an and the Arab Islamic tradition, modern readers should not assume that local secular matters were not the material of poetic expression in Swahili. Religious poems may have been preserved for devotional reasons, but the tradition always also included poems on social and political topics, perhaps even in greater abundance than the former.

One poetic genre from these centuries, the utenzi (or utendi), is often equated with the “epic” in English. Mwengo wa Athumani’s Utendi wa Tambuka (circa 1728) offers a fictional account of battles between the forces of the Prophet Muhammad and those of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius from a Muslim perspective. Another, Mwana Kupona binti Mshamu’s 1858 Utendi wa Mwana Kupona, composed on the poet’s deathbed for her daughter, offers motherly teachings on appropriate conduct for a woman in Swahili society; these are read by some as reinforcing patriarchal values and by others as subverting them. Still other poems in this genre narrate the life and death of Swahili poet Fumo Liyono or contemplate the ruins of the once splendid city of Pate and the ephemeral nature of life. The shorter form, the shairi, often treated social and political matters, such as the violent resistance of the Swahili people of Mombasa to Omani occupation, as well as more intimate and humorous poems about local disputes and personal relations within the Mombasa community.

Contemporary Swahili poetry has tended to adhere to classical structure and poetic conventions, even as it focuses on modern social themes. Santi ya Dhiki (1973) by Kenyan poet Abdilatif Abdalla is a collection of poems written during his political imprisonment from 1969 to 1972 and contains scathing criticism of the government of then-president Jomo Kenyatta. Tanzanian poets Kaluta Amri Abedi and Saadan Kandoro, on the other hand, were adherents of nationalist politics who worked to promote Swahili as Tanzania’s national language. Swahili also saw during this period controversial experimentation with new forms, including free verse, exemplified in the collection Kichomi (1974; Twinge) by Tanzanian Eu-phrase Kezilahabi.

The writer most often associated with both modern transformations of Swahili’s classical poetic forms and the emergence of fiction in Swahili is Tanzanian Shabaan Robert. He is often credited with writing the first novel in Swahili, the utopian Kusadikika (1951; Believable). The late twentieth century saw many new developments in fiction, including the exploration of the inner consciousness of narrators and the rise of popular fiction, such as detective novels, sexually adventurous works, and populist novels, the last often focusing on social inequalities and failed government policies. Still newer trends in fiction can be seen in recent novels, including, for example, Said A. Mohamed’s Babu Alipofufuka (2001; When Grandfather came back to life) and Kezilahabi’s Nagona (1990; The insight), which are “magical,” often are intertextual (referencing other texts), and abandon a realist narrative mode (that is, they do not seek to create the sense of a real, concrete world). A few female feminist novelists have also appeared: Zanzibari Zainab Burhani (Mwisho wa Koja, 1997; The end of the bouquet) and Kenyan Clara Momanyi (Tumaini, 2006).

Major playwrights in Swahili include the prolific Alamin Mazrui of Kenya (Kilio cha Haki, 1981 [Cry for justice], in which a female union leader awakens the political consciousness of her fellow workers) and Tanzanians Penina Muhando (Hatia, 1972 [Guilt], focusing on economic uncertainty and madness) and Ebrahim Hussein (Kinjekitile, 1969; Kwenye Ukingo wa Thim, 1988 [At the Edge of Thim, 2000], both warning against an uncritical embrace of “tradition”). Hussein is considered one of Swahili’s most accomplished authors in any genre, drawing on both Western dramaturgy and Swahili mythological and oral traditions.

While the origins and history of Swahili literature are distinctive, this brief survey may suggest nonetheless the parallels and continuities with other African-language traditions and the Europhone traditions that dominate the study of literature from Africa in the American classroom. Such histories could be written for any number of African languages.

A long-standing debate in African literary circles has focused on the implications and consequences of writing in “national” or now Africanized European languages. Ngugi wa Thiong’o has for many years urged writers to write in African languages. If one follows his argument in Decolonising the Mind (1986), this would seem to be especially a matter both of the inadequacy of non-African languages for conveying African experiences and of the audience for whom the author writes. If writers and intellectuals want to address their compatriots, most of whom are not fluent in European languages, it would make sense that writers write in the languages and aesthetic traditions of those compatriots. This shift in audience will also affect what writers say and the perspectives they offer, and it will foster the growth of African languages and literatures.

Figure 10.4. In Senegal, books can be purchased in bookstores and in open-air markets.

Djibril Sy.

These are good arguments. It is hard to disagree with the idea of communicating with one’s audience in a shared language. And there is indeed a rich and unique expressiveness of each (African) language—what translation theory conceptualizes as the untranslatable. Moreover, pushing the limits of written expression in recently codified languages for which there are historical oral traditions but a dearth of current written literary texts is critical to the development of those languages as flexible contemporary media. So, for example, the Senegalese journalist and novelist Boubacar Boris Diop has written his first novel in Wolof, Doomi Golo (2003; The monkey’s kids).

But the choice of language of expression is not as clear-cut as it may at first seem. Many writers, who have been reading, learning, and writing in European languages since childhood, are as at home in European languages as they are in their maternal languages, perhaps more so. Sony Labou Tansi put it succinctly when he said that any language in which you cry, in which you love, is fully your language. Regrettably, many Europhone authors do not know how to write their mother tongues, and while they revere oral traditions, they themselves may be mediocre oral storytellers. Moreover, most writers are addressing multiple publics, not only those of their own ethnicity but other compatriots who speak different languages, other Africans on the continent and in diasporas from the United States to the Caribbean to Spain, India, and China, and still other readers who are not even especially Africa-identified. Many of the earliest Europhone texts were written precisely to “talk back” to European imperialism. For these reasons, there are many powerful forces—metropolitan publishers, foreign academies and media, paying readerships abroad, and still lower literacy rates in most “national” languages than in European ones—militating against the abandonment of Europhone texts and publishing.

At the same time, there are many thriving African-language literatures, such as those in Amharic, Yoruba, Pulaar, Zulu, and Swahili, as we have seen, and they are increasingly legitimated by school and university curricula, their use as “national” or “official” languages, and the interest of local publishers and ever-growing African readerships.

Another important debate in the field of African literary studies, as in African studies generally, has been the very meaning of the term “African.” Those who define Africa either racially or culturally often look toward the past, “original” (which is to say, precolonial) Africa to locate the signs of African authenticity. They may equate certain forms, such as proverbs and tales, or types of language, such as colloquial or creolized French or English, as the true expressions of Africa and those to which writers of European language texts especially should aspire or which they should emulate.

Others such as philosophers Kwame Anthony Appiah and V. Y. Mudimbe, historian Terence Ranger, and anthropologist Johannes Fabian argue that such supposedly pure, authentic forms and the notion of static “traditional times” are largely invented on the basis of the dubious colonial archive of anthropological, missionary, and administrative documents to which Chinua Achebe refers in the last paragraph of Things Fall Apart. The Arabic-language writer Tayeb el Salih of Sudan (Wedding of Zein, 1969; Season of Migration to the North, 1966) has argued similarly that Africa has always been syncretic.

To champion a narrow African authenticity based on what is ultimately an arbitrarily chosen moment of the past, then, is to ignore Africa’s own complex history of encounters. Depending on the criteria used, it could mean excluding the creative work of writers of Lebanese or Martinican origin in Senegal, for example, or the work of writers of Indian descent in Tanzania and Kenya such as award-winning novelist Moyez Vassanji (The Gunny Sack, 1989; The Book of Secrets, 1994; The In-Between World of Vikram Lall, 2003), for whom Asian African communities’ experiences of colonial oppression and decolonization trouble their relationship to the nation. Similarly, it would, in all likelihood, exclude the work of white writers of British or Afrikaner descent in southern Africa, such as Nadine Gordimer or J. M. Coetzee. Doris Lessing (The Grass Is Singing, 1950; The Golden Notebook, 1962), who grew up in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia), signals the critical, if troubled, identification of these writers with Africa when she states, “All white South African literature is the literature of exile, not from Europe, but from Africa” (Kathryn Wagner, Rereading Nadine Gordimer, 1994).

Narrow claims for authenticity would exclude the fiction of the prolific Egyptian Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz (Zabalawi, 1963; Miramar, 1967), whose Arabic-language texts reveal deep familiarity with literatures of the world. So too the innumerable plays of the innovative Egyptian playwright Tawfiq al-Hakim, who has sought to fuse Egyptian and Western dramatic traditions (The Sultan’s Dilemma, 1960; The Fate of a Cockroach, 1966). It would also mean excluding much of the work of Wole Soyinka, who draws on the mythologies and poetic traditions not only of the Yoruba of Nigeria but of other countries as diverse as Britain, Greece, and Japan. Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman makes this point explicitly: there is no contradiction in being African and riding and embracing the crest of world currents, be they technological or cultural. Africans too have diverse origins, “races,” genders, and sexualities. Let us note, moreover, that this chapter is entitled not “African Literature” but simply, if nonetheless dauntingly, “Literature in Africa.” The period in which “African-ness” might be defined above all by anti-imperialism and anti-racism has passed.

Thus the circumstances in which novels, plays, and poetry, many of them the legacy of imperialism, are produced and studied are as important to our understanding of the practice of literature in Africa as are the style and images on the pages we read. Many factors give African writing its character and at the same time impinge on its development. One of the terrible, ironic testimonies to the vitality of literatures across Africa, to their resolute denunciation of multiple forms of domination, is the fact that writers—Kofi Awoonor, Mongo Beti, Bessie Head, Dennis Brutus, Nuruddin Farah, Abdelatif Laâbi, Jack Mapanje, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nawal el Saadawi, and Wole Soyinka, to name some of the most prominent—are routinely censored or forced into exile, or even incarcerated, tortured, or executed, as was Nigerian Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995. African writers have often wandered, taught, and written on foreign shores because they could not do so at home.

Books by writers residing in Africa are still more likely to be published and marketed in Paris and London than in Dakar or Lagos, and those published in major overseas capitals are more likely to garner international acclaim. Books written by Africans are also more plentiful in university libraries in Europe and the United States, and scholars outside of Africa are more likely to review and critique those books in the prominent and widely read periodicals, newspapers, and publications of the West. American students therefore have far greater access to texts written by Africans than do most African students, who typically cannot afford to buy books, were books available. And within Africa, Francocentric and Anglocentric educational legacies persist.

All these factors come between the reader and the lines on the page when one picks up a book of “African literature.” To insist on such determinants of literature and to contextualize it in this way is also to recognize that our understanding of the field continues to shift. We are far more conscious of the ways in which the factors outlined above are present in texts, of the ways in which new texts revise the meaning of their antecedents, and of the fact that the literary act is a function of the reader and of institutions such as the university, publishing world, professional organizations, and newspapers, as well as of the writer and what is written.

Let us close this survey with reference to two important recent developments in literary production by Africans.

In 1990, Nelson Mandela, antiapartheid activist and leader of the armed wing of the African National Congress, was released by the South African government after twenty-seven years of imprisonment. South Africa proceeded to develop a new constitution and to hold the country’s first democratic elections in which all South Africans, irrespective of “race,” were able to exercise their right to vote. For most of the twentieth century, as we saw above, South African writers of all hues had grappled with the snares of apartheid. With the dismantling of the official policy, the culture of antiapartheid resistance that had shaped South African writing for decades began to crumble. As of the early 1980s, Njabulo Ndebele (Fools and Other Stories, 1983) urged South African writers to abandon the “spectacular” representation of antiapartheid struggle and to “rediscover the ordinary,” to uncover, render, and mine the texture of everyday life for its pains, poignancy, and promise, as he himself does in an innovative novel, The Cry of Winnie Mandela (2003). Today, the South Africans we signaled above continue to write, of course, and a new generation of writers in English has arisen, many of them firmly addressing the complex tapestry of urban life, from poverty, unemployment, prostitution, HIV/AIDS, and xenophobia to hip urban lifestyles and consumer culture: Phaswane Mpe (Welcome to Our Hillbrow, 2001), K. Sello Duiker (Thirteen Cents, 2000; The Quiet Violence of Dreams, 2001), and Niq Mhlongo (Dog Eat Dog, 2004). Ivan Vladislavic mixes fantasy, historical events, recognizable places, and satire in fictions and nonfictions in the tradition of postmodernist aesthetics (The Folly, 1993; The Restless Supermarket, 2001). Imraan Coovadia (The Wedding, 2001; Green-Eyed Thieves, 2006) narrates with endless intertextual references and delightful prose the crises and adventures of Asian Africans both in Africa and in the Americas, while award-winning South African–born novelist and filmmaker Rayda Jacobs brings to this conclave a feminist voice recounting the lives of Muslim women at the intersection of multiple cultures (The Middle Children, 1994; Eyes of the Sky, 1995; Confessions of a Gambler, 2004). Zoë Wicomb, whose much acclaimed You Can’t Get Lost in Capetown (1987) brought to full light the intersections of race and gender under apartheid, has published more recently David’s Story (2000) and Playing in the Light (2006), and Zakes Mda, author of Ways of Dying (1995), a lyrical, magical realist story of possibility in mean circumstances, has brought out The Heart of Redness (2000), which probes historical legacies and social values in contemporary South Africa.

It may be apparent that any number of writers born in Africa no longer reside in their home countries but elsewhere on the continent or abroad. The trickle that began decades ago, due mostly to repressive governments, has become a torrent, not only because of ongoing oppressive and violent regimes but also because of woefully inadequate salaries and living conditions. Nor is it a phenomenon of a single class: while visual artists, writers, and filmmakers may go in search of greater freedom and resources to allow them to think deeply about their home countries and the continent from a distance, it is also the case that traders and a whole generation of youth who are stymied by stagnant economies, lack of education, and viable employment also dream the dream of emigration and opportunity.

Meanwhile, the metropolises of the former European colonizers, with their stringent policies on immigration, are no longer necessarily the destination of choice, but many young Africans, along the Atlantic cost in particular, still risk their lives in fragile boats to reach European shores. For those who survive the journey, life as an illegal immigrant without passport and appropriate documents is harrowing, as we see in Bleu blanc rouge (1998; Blue White Red), the award-winning first novel by Congolese Alain Mabanckou, and I Was an Elephant Salesman (1990; Io, venditore di elefanti), a memoir by Senegalese Pap Khouma. The United States, with its historically dynamic economy and thirst for innovation, has become something of a promised land for many young Africans, who are the most highly educated group of immigrants entering that country. And now China, which has an increasingly important presence on the African continent itself, is also becoming an important destination for African émigrés.

In addition to their maternal languages and other “national” languages, African immigrants speak and write English, French, Portuguese, Dutch, Italian, Japanese, and Chinese. Writers have begun to write not only in the languages of erstwhile colonizers in which they were schooled but in languages they come to choose. Thus, the Senegalese professor and novelist Gorgui Dieng, who remains in Senegal, writes, by choice, in English (A Leap out of the Dark, 2002); Pap Khouma, mentioned above, writes in the language of the country where he resides and works as a street vendor, Italian. The bright, talented Ibo novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who has been educated largely in the United States, where she resides, writes in English of the Biafran war and contemporary political repression in her native Nigeria (Purple Hibiscus, 2003; Half of a Yellow Sun, 2006; The Thing Around Your Neck, 2009), whereas her compatriot Chikwe Unigwe, who lives in Belgium and writes in Dutch—which she translates for subsequent publication in English—has produced a remarkable novel about African sex workers in Antwerp (On Black Sisters’ Street, 2011).

Algerian Assia Djebar resides and teaches in the United States, as do Nigerian Chinua Achebe, South African Zakes Mda, and Kenyan Ngugi wa Thiong’o. South African Zoë Wicomb has taught and written in both Scotland and South Africa. J. M. Coetzee of South Africa now resides in Australia. Nigerian Kole Omotoso, author of the historical novel Just Before Dawn (1988), works and resides in South Africa. For a decade or more, Somali Nuruddin Farah laid roots first in Nigeria, then in South Africa. Moyez Vassanji lives and writes in Canada. Congolese writer Alain Mabanckou teaches and writes in the United States. Calixthe Beyala of Cameroon, well known for her early strident feminist novels C’est le soleil qui m’a brûlée (1987 [The Sun Hath Looked Upon Me, 1996]) and Tu t’appelleras Tanga (1988 [Your Name Shall Be Tanga, 1996]) and Fatou Diome of Senegal, author of a novel whose heroine continually negotiates the space between home and abroad, Le ventre de l’Atlantique (2003 [The Belly of the Atlantic, 2008]), live and write in France, as do Nabile Farès of Algeria (Un passager de l’occident, 1971 [A traveler through the West]) and Tahar Ben Jelloun of Morocco (L’enfant de sable, 1985 [The sand child]). France has also been home to writers whose parents are French and African—Leila Sebbar (Shérazade, 1982), Bessora (53 cm, 1999) and Marie Ndiaye (Trois femmes puissantes, 2009 [Three powerful women]). Senegalese novelist Ken Bugul lived for many years in Benin. South African Rayda Jacobs lived in Canada for twenty-seven years. Ivorian Véronique Tadjo, who lived for a number of years in Kenya, now teaches and writes in South Africa. And just a few years ago, Senegalese Boubacar Boris Diop divided his time between Mexico, Tunisia, and South Africa. Whatever its roots, this crisscrossing of the continent and the globe has created a broad range of experimentation and new trends in “African” writing that we may justifiably think of as transnational and diasporic.

With thanks to Akin Adesokan and Natasha Vaubel. Special thanks to Meg Arenberg for her contribution to the Swahili literature section.