13 |

Development in Africa |

Tempered Hope |

Sub-Saharan Africa, home to more than eight hundred million people in more than fifty countries, is the least-developed continent in the world. It continues to have relatively low levels of industrialization and urbanization, and instead subsists on narrow economic bases, overly dependent on primary commodities and foreign aid. Livelihoods and life chances on the continent are often among the most challenged in the world, with low life expectancy (especially with the impact of HIV/AIDS), literacy rates, and access to health care and education. Moreover, governance institutions are weak, as evidenced by the fragility of democracies emerging after three decades of authoritarianism, heavily politicized bureaucracies and judiciaries, and weak policy environments that frequently respond more to patronage networks than to competitive ideas and interests. African economies have grown slowly since the early years of independence in the late 1950s and 1960s compared to those of other nations, especially in Asia, that came into independence at the same time. By 1980, real average incomes had regressed to below the levels of the 1960s. Predictably, Africa is the only continent expected not to meet any of the eight Millennium Development Goals adopted by the United Nations in 2000 to combat the most significant development challenges by 2015.

Not surprisingly, the recent global economic crisis is likely to affect growth, given the slump in demand from high-income countries for primary products from sub-Saharan African countries. In addition, declines in direct investment and remittances from nationals living abroad and a reduction in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows will dim growth prospects.

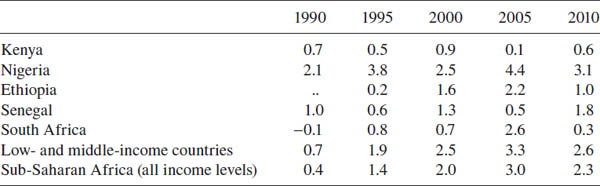

Yet there have been remarkable strides in some development and economic indicators. The investment climate for several African countries has improved due to the adoption of sound macroeconomic policies. In many countries, inflation has been reduced to single digits; at the regional level, rates of inflation are almost half what they were in the 1990s. Additional emphasis on exchange rate stabilization—important for investors’ inputs and profit estimations—has bolstered investor confidence, leading to an increase in regional FDI and to a rise in net inflows as a percentage of GDP from 2 percent in 1998 to about 3 percent in 2010.1More important, several countries in the region, such as Cape Verde, Sierra Leone, and Burundi, have initiated reforms that have made doing business easier. In fact, the World Bank’s Doing Business Report (2012), the leading review of investment climates, declared Africa one of the fastest-reforming regions in 2009; in 2012, it indicated that a record thirty-six out of forty-six economies improved their business regulations during that year alone. The cumulative effect of these reforms—seen in growth rates especially—forces us to reconsider the crisis perspective that dominated most discussions of African development in the 1980s and 1990s, perhaps switching to one of renewal or, given uneven gains and fragile conditions, at least tempered hope.

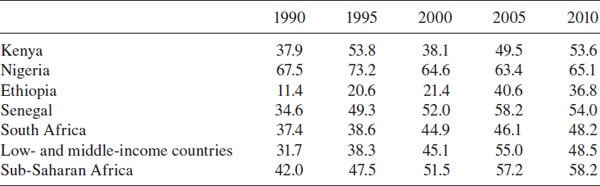

TABLE 13.1. Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP)

In the service delivery realm, marked improvements are evident in several sectors. Primary school completion rates improved from about 50 percent in 2000 to 67 percent in 2009. Similarly, enrollments for both boys and girls have improved—often as a consequence of a return to universal free education, largely due to political pressure faced by democratically elected governments. In recent years, the region has also experienced increased penetration of mobile telephony and internet connectivity, which is a direct consequence of the liberalization of a sector that had almost universally been under loss-making state-owned corporations in the 1980s. The proportion of internet users increased from less than 1 percent in 2000 to about 11 percent in 2010. Similarly, by 2010 one out two Africans had a mobile cellular subscription. A number of trends in the international discourse and practice around development have helped push institutional reforms in African countries and mutual accountability between the countries and development aid donors. The Organization of African Unity transformed into the African Union (AU), with a new post-Cold War outlook that demands and, more often than not, enforces adherence to core principles of democratic government. Moreover, the introduction of the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) through the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD) elevated the mutual obligations governments and leaders have over internal governance. The APRM also “encouraged . . . the sharing of experiences among participating member states on best practices across the region to ensure cross country learning for capacity building.’ ”2 Efforts by multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, the G-8 (i.e., the eight largest economies in the world), and the European Union have helped shift attention to growth and development in Africa, promising more aid in exchange for better governance practices and, for the World Bank especially, a focus on poverty reduction. This renewed attention to the development imperative in Africa has been complemented by initiatives around improving conditions of trade, such as the United States’ Africa Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA), the EU’s Everything but Arms Initiative, and the United Kingdom’s Africa Commission. An overriding commonality in all of these frameworks is a focus on nationally owned development strategies instead of prescriptions and conditions from foreign governments and donors, an emphasis on sustaining institutional governance and peer review instead of a hands-off attitude toward misgovernance, and an increase in aid volumes to reverse the stubborn lack of progress in development indices on the continent.

Overall, the retreat from deep crisis has left a mixed picture—remarkable success in some countries, reversal or decline (often after a promising start) in others. In this mix of fortunes lie some important lessons for development in Africa. This chapter reviews the status of different aspects of development and the underlying transitions that seem to drive the respective outcomes. It is clear that while the global environment (e.g., the availability of aid or FDI) and regional trends (such as a decline in conflict and a rise in regional integration) continue to have a large impact, by far the most important factors are homegrown: national policies, institutional strength, and government performance in providing public goods.

The oil crises of the 1970s and 1980s and the subsequent drying up of credit facilities from international markets led to a rise in interest rates, making it difficult for African countries to borrow. More important, these crises led to a rise in the trade deficit from $22.2 billion in 1979 to $91.6 billion in 1981. The current account deficit rose from $31.3 billion in 1979 to $118.6 billion in 1981 (Hart and Spiro 1997: 179). At the same time, it became difficult for these countries to continue servicing their debts, and debt arrears grew at a rate surpassing that of new lending. As private lenders became increasingly wary of lending to developing countries, it became clear that African countries would not be able to meet their debt obligations. Growth rates declined, inflation rose, and both industrial and agricultural sectors suffered. Africa had officially entered what is known as its “lost decade.”

In subsequent years, external debt rose and the balance of payments worsened. Action to correct distortions in African economies and put the continent on a path to stabilization seemed inevitable. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (also known as the Bretton Woods institutions) became the continent’s lenders of last resort, giving them outsized leverage over African governments. Because of the dire economic conditions, including an inability to meet their debt obligations, African countries were forced to adopt a set of policies called structural adjustment programs. In exchange for development credits from the World Bank and short-term balance-of-payments support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), African governments adopted policy changes to limit the role of the state in the economy (especially direct investment), and to reduce expenditures, especially in social sectors and for subsidies. The IMF insisted that African governments remove government controls on prices and open up their economies to free trade. It was expected that these austerity measures would enhance economic growth and ensure macroeconomic stability over time. African countries had been reluctant to initiate structural adjustment programs, but in the mid-1980s and 1990s, thirty-six countries agreed to the conditions. Among the late entrants were Nigeria and Mozambique, beneficiaries of debt relief under the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, a World Bank program to assist countries manage their debt burden and allocate savings and new funds to social sectors that had been deeply affected by austerity under adjustment.

With the onset of structural adjustment, the management of African economies would undergo close scrutiny by the Bretton Woods institutions, much to the resentment of Africans. Yet the structural adjustment programs did not produce quick results, and soon African citizens were criticizing their governments for ceding too much to international institutions and further impoverishing them. Politically these policies became untenable, and their economic value was open to question and sometimes even ridicule. Violent confrontations with citizens resulted in several countries, notably Zambia, Kenya, and Nigeria. Leading Africanist scholars and institutions such as the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) began to question the rationale of structural adjustment and offered alternative frameworks for achieving the same objectives. The African Alternative Framework to Structural Adjustment Programs, presented by UNECA, proposed a state-centered approach to the management of Africa’s economic affairs, while also attributing Africa’s problems to external forces. African leaders—for example, Kenya’s Daniel arap Moi—soon began to waver on implementation of structural adjustment while some abandoned it altogether because of the political costs. Soon, even the World Bank would admit that structural adjustment might not have been good for African countries. A new approach for dealing with African development had to be devised, one that espoused country ownership and broad public participation.

The introduction of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers by the World Bank as the policy instrument to inform development assistance to low-income countries helped transfer the burden of designing programs to the developing countries themselves. However, for Africa specifically, the World Bank moved a step further and created the Africa Action Plan (AAP), a document reiterating the role of individual countries and of the partnership arrangements between the bank and African countries in the effort to help Africa reach the targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The AAP identifies four key areas of partnership: accelerating shared growth, building capable states, sharpening focus on results, and strengthening and developing partnerships.

Africa has shown remarkable improvement in key socioeconomic indicators. Annual growth rates have improved, mortality rates for children under five have been falling; and the number of people living in poverty (defined as earning less than $1.25 a day) has declined. However, there is continued and widespread poverty and often discontent, especially where jobs do not accompany growth. By 2007, only slightly over one-half of Africa’s working-age population was employed in the formal economy. Women’s participation was even lower. And even employment has not guaranteed quality of life, as many of these people are “working poor,” living in households where each member earns less than $1 a day. Compared with other regions, the momentum for poverty reduction in Africa has not been great. Nevertheless, there are significant cross-country variations, as some countries are already showing promising growth patterns.

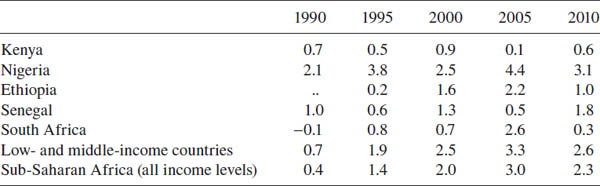

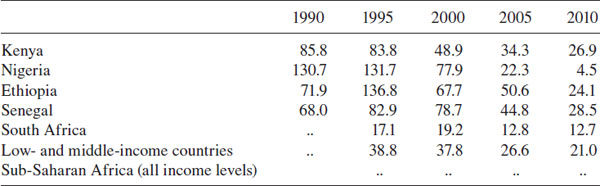

Economic performance in sub-Saharan Africa has continued to improve. During the 1990s, GDP growth averaged only 2.4 percent; from 2000 to 2004, however, GDP growth averaged 4 percent, and the rate rose to 5 percent by 2010. This new surge in growth has been fueled in part by high oil prices, increased demand from China, and a booming mineral and oil market. But a temporary slump to 2.0 percent in 2009 as a result of the global financial crisis also reveals Africa’s vulnerability to shocks in the global economy. Key macroeconomic indicators such as inflation, exchange rates, and fiscal deficits have stabilized remarkably. For most African countries, the main hindrances to sustainable growth have been identified as excessive regulatory reform, institutional constraints, and weak infrastructure (World Bank 2005: 19).

Once-promising countries such as Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria have been victims of weak leadership, corruption, dictatorship, and wide variations in the provision of social services. This has not only led to a significant departure of highly skilled professionals but also contributed to poor utilization of available resources, politically motivated investment decisions, and lack of transparency and accountability. In places such as Zimbabwe, it has led to a total breakdown in the structures of governance, leading to an unprecedented near collapse of the economy. In Kenya and Nigeria, corruption has discouraged investors and contributed to low investment numbers, while inequality contributed to political discontent, resulting in conflict in Kenya in 2008. Regulatory and bureaucratic hindrances have undermined investor confidence, slowed growth, and contributed to the stereotype of Africa as a region in crisis. On the whole, the norm of good governance has taken root in Africa, as shown by the assiduous attention citizens and governments are paying to numerous indicators. In practice, however, good governance still remains elusive in many countries, as demonstrated by recent upheavals in Mali, Guinea, and Senegal.

TABLE 13.2. GDP GROWTH (ANNUAL %)

In the last decade, violent conflict has declined significantly at the global level. Much of this decline is attributable to the reduction of conflict in Africa. Countries such as Angola and Mozambique, long marred by civil war, are now thriving. Others such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, although they have settled their internal wars, continue on a precarious path to economic recovery. Still others, such as Somalia and Eritrea, remain economically unviable due to conflict and severe declines in governance. In certain places conflict produces dual realities. For instance, both Sudan and South Sudan have thriving oil sectors and growth but are likely to be undermined by the conflict in Darfur and increasing hostilities following the independence of South Sudan in 2011.

While significant challenges remain in demobilization and reintegration, and the threat of resurgent conflict remains all too real, the reduction in violence in several countries has opened them up to new investment and participation in the region’s economic development. But such peace dividends are often feeble and fragile; building trust and capacity, as well as reconstituting social and economic integrity for refugees and internally displaced persons, remain elusive. Indeed, refugees and internally displaced persons pose special challenges. At the end of 2010, there were about three million refugees in Africa, representing about 20 percent of world refugee totals; the number of internally displaced persons was about six million by the end of 2010, representing about 42 percent of the world total, according to the UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database. This undermines productive participation in the economy and perpetuates the cycle of poverty. For Africa, the voluntary repatriation of refugees in countries such as South Sudan, Liberia, Burundi, and Democratic Republic of the Congo helped reduce the number of refugees in the region. More important, it underlined the gradual reconstruction of these hitherto strife-torn countries and augured the eventual participation of the returnees in the region’s economic development.

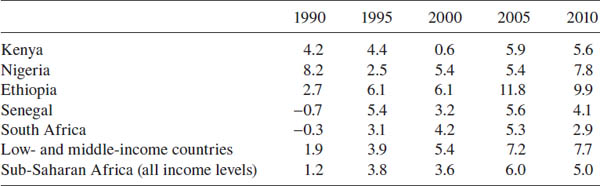

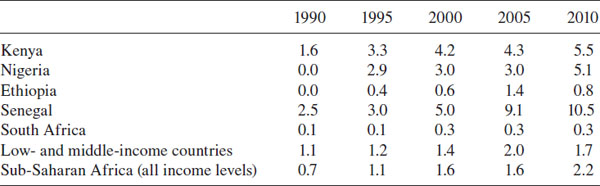

In 2010, Africa’s population was estimated to be 854 million. About 43 percent of this population was under the age of fifteen. Sub-Saharan Africa’s average annual population growth rate of 2.5 percent (in 2010) is the highest in the world—it is almost double the world average, and is expected to remain at that level until 2015. Countries such as Kenya and Nigeria have average annual population growth rates that are even higher, about 3 percent. It is estimated that by 2050 Africa will account for 21 percent of the world’s population, according to the UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database. Still, Africa’s population growth rate has declined significantly in the last half century (it was 14 percent in 1960) and now is almost on par with that of other developing countries, which averaged 1.9 percent in 2005. One of the most worrying trends in African population growth is that the majority of Africa’s population is concentrated in the fifteen-to-twenty-four age bracket. The resultant “youth bulge” has serious implications for individual countries regarding opportunities for gainful employment and service delivery (especially housing, education, and health). Furthermore, the urban population accounts for 39.6 percent of total population, with about two-thirds of urban dwellers living in slums.

When the pace of economic growth is countered by the pace of population growth, durable reductions in poverty can be difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, an important outcome of population growth and the decline in median age has been an overall decrease in the dependency ratio (the ratio of the very young and very old to those of working age). In 1995, Africa had 91 dependent people for every 100 people of working age; by 2010, the proportion of the population that depends on the working-age population had declined to 85 per 100. While that ratio is still very high compared to the global average of 54 percent, it nevertheless shows a positive trend.

HIV/AIDS remains one of the biggest obstacles to economic growth in Africa. Rapidly growing economies such as South Africa and Botswana have been hobbled by high levels of HIV/AIDS infection. In 1990, about 5 percent of Botswana’s adult population (ages fifteen to forty-nine) was infected. By 2010 this number had risen to about 25 percent. Similarly, in South Africa, rates of infection have grown from less than 1 percent in 1990 to about 18 percent in 2010. However, new and innovative measures to control the pandemic seem to be yielding the desired outcomes, as the proportion of adults with HIV/AIDS is dropping in some countries. For example, Uganda experienced huge rates of infection in the 1990s, with a prevalence of almost 14 percent. By 2010, HIV prevalence in that country had declined to about 7 percent, the result of an aggressive intervention program by the government. Similarly, Rwanda reduced its prevalence from about 9 percent in 1990 to about 3 percent in 2010, and Congo from about 5 percent in 1990 to 3 percent in 2010. Still, HIV prevalence among adults is highest in Africa, where overall about 5 percent of those fifteen to forty-nine are infected. This is a stark difference from other developing regions such as South Asia or Latin America and the Caribbean, where prevalence in this age group is still below 1 percent. Nevertheless, countries such as Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia have consistently maintained prevalence rates of about 2 percent for a decade.

TABLE 13.3. Population growth (annual %)

One of the most important avenues for reducing Africa’s dependence on aid is through increased and fair trade. The transformations in the international system after the Cold War imposed serious setbacks in Africa’s relations with countries of the North. Preferential trade agreements were replaced with the more stringent requirements of the World Trade Organization (WTO), which, while expected to have long-term benefits for free trade, impose severe disadvantages in the short term. For instance, under WTO rules, there has been a decline in the share of agricultural exports from Africa (as a share of merchandise exports) between 1995 and 2004. From a high of 6.8 percent in 1996, it dropped to about 4.4 percent in 2002, and remained there as of 2010. Given that Africa relies on agriculture as its main economic output, a skewed international agricultural market system has had adverse effects. This is even more critical given the fact that almost two-thirds of Africa’s labor force is employed in agricultural sectors.

Developed countries continue to provide subsidies to their farmers. Added to existing tariff and non-tariff barriers, this creates market distortions that undermine Africa’s participation in global agricultural markets. The relatively small size of most African countries has increased their vulnerability as global players in the international trade system. It is no wonder that many nongovernmental organizations as well as African leaders themselves have increasingly called for a fairer international trade system. Nevertheless, as witnessed during global trade meetings in Doha in 2010 (known as the Doha Round), African countries, alongside other developing regions, have repeatedly tried to force consideration of issues that affect them, lobbying for reduction of tariffs for primary goods imported by the wealthy nations and compensation for short-term ill effects of further trade liberalization. However, since these trade negotiations are often years in the making, the kind of regime that would induce massive poverty-reducing growth remains elusive.

In the last decade, some African countries have proved that, given a fair trade regime internationally and pro-growth economic policies at home, the continent is capable of competing in the international market. Malawi, for instance, has recently become a net exporter of agricultural products, while Kenya is increasingly carving out a niche in horticultural products globally. Overall, there has been an increase in Africa’s participation in global trade. This increased trade volume supported the increased growth in GDP for many African countries. The region itself experienced a sharp rise in trade as a percentage of GDP, with that figure growing consistently from 50 percent in 1990 to about 76 percent in 2006 before succumbing to the global economic crisis and dropping to 65 percent in 2010. Most of this trade occurred between Africa and other developing regions; the proportion of merchandise exports to developing countries outside the region increased from 15 percent in 2000 to 32 percent in 2010. Within the region, exports to developing countries remained relatively flat at an average of 12 percent between 2000 and 2010 in spite of several regional agreements and trading blocs. Conversely, the proportion of merchandise exports from Africa to high-income countries peaked at 67 percent in 2005 before gradually dropping to about 54 percent in 2010.

TABLE 13.4. Merchandise trade (% of GDP)

Africa’s merchandise imports from within the region have remained low, hovering between 12 and 13 percent from 2000 to 2010. But it imported more from other developing countries outside of the region, with the total almost doubling from 15 percent of merchandise imports to 30 percent in 2010. The increase in both merchandise exports and imports is partially attributable to the role of China in African markets. The low export figures are indicative of the protectionist nature of developed-country markets and the significant barriers that African countries still confront in accessing them. In addition, the 2008 financial crisis has had an ongoing effect on trade volumes, with export figures slumping in the first quarter of 2009 in developing countries as demand for commodities and agricultural raw materials slowed in developed regions.

During the last decade, the extractives industry in Africa (and elsewhere) continued to grow, fueled by huge demands by China. Consequently, oil-and mineral-producing countries have witnessed remarkable growth in the last ten years. Angola, Chad, Nigeria, and Sudan have shown growth patterns similar to those of high-income countries, each doubling its annual GDP growth rate between 1995 and 2005. This has increased sub-Saharan Africa’s industrial growth rate from an average of 2.0 percent in the 1990s to 5.2 percent in the 2000s. It is conceivable that the lack of industrial infrastructure to process much of Africa’s raw materials, including natural resources such as crude oil, undermines the continent’s competitiveness. The windfall for oil-producing countries has been a curse for the many countries in Africa that import oil, as they have been forced to spend more in buying crude and other petroleum products.

TABLE 13.5. External debt stocks (% of GNI)

Africa is also saddled with a large amount of external debt. To be sure, the size of the total external debt has been decreasing in the last decade. Total debt service as a percentage of gross national income (GNI) has been declining in Africa at an impressive rate, from 4 percent in 2000 to 1 percent in 2010. Still, the majority of African countries continue to remit a significant portion of their national earnings to international creditors. Africa’s external debt almost tripled between 1980 and 1990, from $60 billion to about $180 billion, largely as the result of the external shocks such as the oil and debt crises of the 1970s and the attendant rise in interest rates. By 2007, the total debt owed by African countries was about $195 billion, a drop from a peak of $240 billion in 1995. This reduction in external debt is largely accounted for by the debt relief arrangements under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries’ (HIPC) Initiative created by international development partners, through the World Bank, to facilitate debt forgiveness to poor countries with large debts. Countries such as Mozambique that have benefited from this program continue to show signs of accelerated growth, with the growth rate rising from 1 percent in 1990 to 3 percent in 1995 and then to about 8 percent in 2005. However, it is important to point out that debt relief by itself does not drive growth. After a protracted civil war, Mozambique has benefited from relatively stable political conditions, low corruption, and consistent pro-growth economic policies.

While a large portion of foreign direct investment targets developed countries, Africa has seen a rise in FDI flows in recent years. The majority of this flow has been from China, India, and Brazil, with China investing in resource extraction and infrastructure, Brazil in railway construction, and India in agriculture. FDI from these and other countries constitutes a significant proportion of private financing. In 1990, FDI flows accounted for only 0.4 percent of Africa’s GDP. By 2005, this had risen sevenfold, to 2.8 percent. By 2009 it accounted for about 4 percent of GDP, double the world average. Much of this flow was accounted for by increased investments in commodities such as oil and minerals. Some of Africa’s top recipients of increased FDI flows in recent years are those with mineral deposits and oil. In Equatorial Guinea, for example, FDI flows as a proportion of GDP rose from 8 percent in 1990 to about 19 percent in 2006. Sudan, Chad, and Nigeria, with both oil and other natural resources, have seen similar increases. Africa as a whole has also recorded a rise in average rates of growth in manufacturing from 2.1 percent in the 1990 to 3.2 percent in the 2000s.

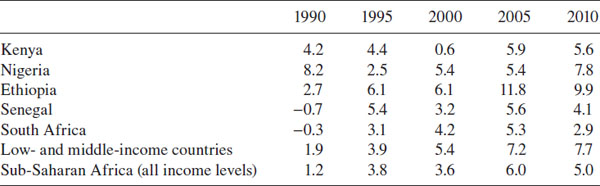

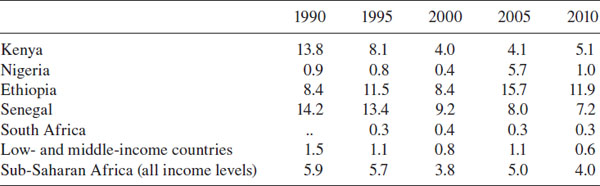

TABLE 13.6. Workers’ remittances and compensation of employees, received (% of GDP)

Additionally, a significant amount of Africa’s foreign exchange earnings has been through remittances from migrants abroad. It has been estimated that remittances to developing countries are double the amount of foreign aid and almost two-thirds the amount of FDI (World Bank 2008: x). The emergence of migrant remittances as a significant source of external financing for African countries has led to a focus on the role of African citizens abroad in financing development in their home countries. In 2010, remittances constituted about 2.2 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP, slightly above the average for low-and middle-income countries, which was about 1.7 percent. At the country level, remittances constituted 11 percent of GDP in Senegal, 8 percent of GDP in Cape Verde, and about 5 percent of GDP in Nigeria. While this is good for Africa in the short term, dependence on remittances remains a high risk given the volatility in the global economic environment.

The entry of China into Africa has raised serious implications for Western lenders and donors. While these trade, aid, and investment partners have insisted on liberal notions of good governance and democracy and limited state ownership of economic enterprises, China has tended to downplay the relevance of those ideals in its dealings with Africa. The surge in the volume of trade with China has made it possible for some countries to survive cuts in aid and in balance-of-payments support. Africa’s exports to China increased at an annual rate of 48 percent between 2000 and 2005. China continues to court African countries that have been labeled “rogue states” by the West. For example, in the past decade, China increased trade with Sudan, South Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, and Zimbabwe. China’s industrial expansion has fueled its demand for oil and minerals. As a result, China has encouraged its corporations, especially state-owned companies, to increase trade with African countries. It also established demonstration centers in Africa to showcase Chinese technology and agricultural techniques, and it created the China Africa Fund, a multibillion-dollar investment fund to support companies investing in Africa. China is emerging as an important partner for Africa in the region’s efforts to recover from the shocks of the global economic crisis.

The recent spurt in growth in many African countries can partly be attributed to new trade with China in the last decade. Geopolitically, Chinese interest in Africa has encouraged a “looking East” strategy that has increased the prospects of African states weaning themselves politically from years of dependence on Western countries. While this still appears to be a distant prospect, its realization is not entirely improbable. More immediately, it engenders tensions with the West and Western-dominated international financial institutions, which will likely lead to new patterns of development assistance and possible outcomes. However, an important question regarding this new relationship is whether Africa has the economic capacity to exploit the Chinese market in order to forestall the trade imbalance that is characteristic of the North-South relationship.

State strength and ability to deliver services in an efficient and accountable manner depend on the vitality of state institutions. These, in turn, rely on good governance, which includes free and fair elections, respect for individual liberties and property rights, a free and vibrant press, an open and impartial judiciary, well-informed and strong legislative structures, and engaged citizens. Thus, the fate of Africa’s economic development is intricately interwoven with the establishment of a broad system of capable political and economic governance. African countries have rapidly liberalized over the past two decades. While some countries have lost earlier gains, there has been an increase in the number of countries satisfying minimal democratic requirements. In recent years, efforts to build democratic institutions in Africa have begun to pick up momentum. New programs on democracy and good governance have concentrated on electoral systems, civil society participation, transitional justice, and human rights. Attention has also been given to civil service reform, judicial reform, and public financial management. In countries such as Rwanda, Kenya, and Ghana, attention has been given to institutional and constitutional reforms intended to establish a robust public sector capacity. Additionally, many African countries have realized that prudent management of extractive industry resources is critical for economic growth and that mismanagement of these resources is often among the causes of strife in resource-rich countries. Consequently, many have committed themselves to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). For example, Liberia was the first country in Africa to be accredited by the EITI. It has since made remarkable progress in creating a system for documenting natural resource revenues.

The international development community has played an important role in setting the pace for these developments. Nevertheless, in recent years, domestic pushes for institutional reform and transformation of the region’s political power—a phenomenon known as “demand-side governance”—have gained momentum as citizens, organized in groups or as individuals, have demanded a greater say in governing their communities, more scrutiny of government action, and more substantive and equitably shared outcomes from public resources. Citizens and civil society are becoming more assertive in demanding good governance in places such as Uganda, where citizen scorecards track the performance of elected officials, and in Kenya, where the introduction of performance contracts has introduced a sense of public accountability among senior civil servants. Many countries have seen the emergence of a strong and active civil society—organizations that are autonomous from the state, such as trade unions, interest groups and NGOs, and a free and vibrant press—as a counterweight to unfettered state power. These organizations have been important voices in demanding transparency and accountability from government and in pursuing specific policies that benefit groups such as farmers and industrialists, etc.), and therefore are beginning to re-shape both politics and policies.

There has been an increase in democracy and the acceptance of good governance principles in the majority of African countries since the early 1990s, according to Freedom House. In 2009, ten African countries were rated “free,” twenty-three were rated “partly free,” and fifteen were rated “not free.” While these figures are a far cry from what the wave of democratization in the 1990s had hoped to achieve, they do suggest that Africa’s march toward democracy has continued in the last three decades. In 1980, only four African countries were rated “free,” and twenty-seven were rated “not free” (Freedom House 2009). Overall, there has been an improvement, if a modest one, in political and civil liberties in the last two decades. Still, improvement in democratic freedoms in some countries is offset by decline in others (Puddington 2012).

The World Bank’s own review of institutional capacity, the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment, places most African countries above a 3.5 rating on a 6.0 scale with regard to performance of their public sector management institutions. However, significant variations exist between high-performing countries such as Cape Verde, Ghana, and Tanzania, on the one hand, and low performers such as Angola, Chad, and Zimbabwe, on the other hand. One of the best indicators of good governance is how successful a government is in controlling corruption. In its 2011 Corruption Perception Index, Transparency International found that only three countries (Botswana, Mauritius, and Cape Verde) scored above the midpoint of its scale. Those three ranked thirty-sixth, forty-first, and forty-sixth, respectively, out of the global total of 182 countries. An important development on the issue of governance and development in Africa was the establishment in 2003 of the African Peer Review Mechanism, mentioned earlier in this chapter. Under this mechanism, individual countries are expected to make annual reports to a panel of African leaders on the progress that each country is making regarding the management of public affairs. By June 2012, some thirty-three African countries had signed up to be part of APRM, and some among them, such as Kenya, Benin, Rwanda, and South Africa, had been subjected to review (Wikipedia 2012). In this regard, the African Union has become more assertive in ensuring adherence to democratic principles, at least in terms of a movement toward a culture of respecting the ballot as the final arbiter of political contests. It has acted to suspend errant member countries and refused to recognize leaders that obtain power through violent means. The recent suspensions of Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Egypt, Madagascar, and Guinea point to a more assertive African Union. Nevertheless, its reluctance to intervene in Libya and increasing condemnation of the International Criminal Court over the latter’s alleged bias against Africa have undermined its focus on good governance.

The continent has recently witnessed an unprecedented number of peaceful elections and transfers of power in countries such as Botswana, Ghana, Senegal, South Africa, and Zambia. However, in Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, age-old schisms combined with proximate causes led to violence and instability. The democratic gains of the 1990s, which were fueled by changes in the international system after the end of the Cold War, have been under threat. The return of coups d’état in places such as Côte d’Ivoire, Comoros, Guinea, and Madagascar signal that the dangers posed by instability and political violence are not over. It is, however, too early to conclude that the continent is experiencing a retreat of democracy and a return to the political instability that defined the 1970s.

While the link between good governance and economic growth still remains to be definitively demonstrated in the literature, there is nevertheless a positive correlation; it is also intuitively attractive. Not surprisingly, the fastest-growing economies in Africa are also those that show the most transparency, are better managed in terms of well-regulated but open markets and stable policies, and adhere to the rule of law. Levy (2006) identifies three groups of African countries in terms of their response to structural adjustment. The “sustained adjusters” maintained their reform agenda during the adjustment period of 1988 to 1996; the “late adjusters” initially encountered some internal contentiousness but began reforms in the later part of the 1990s and continued until 2001; and finally the “polarized” countries initiated a few reforms, ignored others, and encountered domestic political problems that undermined sustained reforms. Levy and others find that growth among the first group was higher than in the rest of the countries. Cumulatively, over the 1990s, Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Uganda, and Zambia have experienced consistent upward growth patterns due to consistency in reforms, compared with Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Nigeria, Togo, and Zimbabwe, where reforms were sporadic or reversed. The result: an exacerbation of existing tensions or even convulsions in a number of countries in the latter group at the beginning of the twenty-first century, with contested elections and sporadic violence in Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Côte d’Ivoire and weak national security regimes occasioned largely by porous borders and religious fundamentalists in both Nigeria and Kenya.

While the last decade has witnessed a significant increase in the volume of aid to Africa, it has also been a decade of intense debate regarding the usefulness of aid to the region. Opinion is still divided, with one school of thought claiming that aid has undermined growth in Africa, while the other argues that rich countries have not done enough to support Africa through aid. However, it is a fact that the majority of African countries depend on official development assistance (ODA). After a temporary decline from 31 percent of gross capital formation in 1995 to 23 percent in 2000, ODA rose again to 30 percent by 2006, the result of increased global commitment to development funding by the industrialized countries. However, by 2010 it had dropped again, to 19 percent. Nevertheless, net ODA per capita has been increasing since 1995. In 1995, that figure was $32; by 2007 it was $45, and it rose to $53 by 2010. For example, in Eritrea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, aid as a percentage of GNI has consistently averaged over 50 percent in the last half of this decade. Conversely, Mauritius, South Africa, and Gabon have consistently maintained rates below 1 percent.

Globally, ODA has been on the rise in recent years, largely due to a concerted effort by developed countries to support Africa’s development. This growth is a result of a vigorous push by Northern countries to increase aid to Africa and to improve its effectiveness. During the Gleneagles summit in 2005, leaders of the G-8 countries committed themselves to increasing aid by $25 billion annually. Subsequently, there have been improvements in aid flows, and many countries are on track to meet their commitments. But there has also been a realization that for most African countries, aid has not served the purpose of lifting millions out of poverty. Within the development community itself, it has led to intense soul-searching as to whether aid actually works. Yet, for the most part, it is generally agreed that the positive growth rates, improvements in school enrollment, and reduction in child mortality rates that African countries have experienced in the last decade have largely been the result of increased aid and the significant debt relief many African countries received as a result of the HIPC. In 2005, the Paris Declaration established the principle that governments receiving development assistance need to have control over how to spend donor funds. It emphasized country ownership and called for greater streamlining of how development assistance was distributed and utilized by recipient countries.

TABLE 13.7. Net ODA received (% of GDP)

Despite a decade of impressive growth, it would not be prudent to declare that Africa has turned the corner on development; however, it is reasonable to suggest that earlier pessimism about Africa’s prospects in the twenty-first century was misplaced. Yet the issues that raised those serious doubts at the turn of the century remain relevant to the fate of development success. Tasks such as improving governance, investing in people, increasing competitiveness, and reducing aid dependency still remain critical to achieving regional economic transformation.

While significant variations exist among countries, on average the continent is moving toward accepting the basic principles of good governance, adhering to globally accepted principles of public financial management, and improving its investment climate. Added to the efforts African countries are making in improving chances for young people to enroll in school, providing resources to ensure primary school completion, and enhancing women’s participation in the economy, these are expected to cumulatively result in better socioeconomic standards in the future.

Within the region itself, several countries are emerging as success stories: growing at impressive rates, reforming their governance systems, improving private sector participation, and tackling social problems by improving service delivery. But challenges remain. Africa is still the region with the slowest movement toward the achievement of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, still the region where corruption remains rampant, and still the region where breakdown into violent conflict is the likeliest. The continued existence of fragile states in places such as Somalia, political instability in Madagascar and Guinea-Bissau, and conflict in Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Darfur region of Sudan complicate the prospects for wider economic revitalization. Ultimately, economic development on the continent will not take a uniform path, nor will every African country experience transformation instantly. However, as evidence from Mozambique, Tanzania, and Rwanda has shown, sustained economic growth is possible provided that there is a conscious decision by those in authority to institute sound macroeconomic policies, invest in people, curb corruption, and improve the investment climate. Development partners can give aid, but no amount of external assistance can supplant the domestic commitment to social, political, and economic transformation.

African Peer Review Mechanism. Instrument created by members of the African Union as an African self-monitoring mechanism.

Balance of payments. System of recording a country’s economic transaction with other countries in the international system. It may be favorable or unfavorable.

Civil society. The arena of uncoerced collective action around shared interests, purposes, and values. It embraces a diversity of spaces, actors and institutional forms, varying in their degree of formality, autonomy, and power.

Country Policy and Institutional Assessment. Measures the extent to which a country’s policy and institutional framework support sustainable growth and poverty reduction, and consequently the effective use of development assistance.

Current Account Deficit. Occurs when a country’s total imports of goods, services, and transfers is greater than the country’s total export of goods, services, and transfers.

Dependency ratio. Ratio of those of non-active age to those of active age in a given population.

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Global standard that aims to strengthen governance by improving transparency and accountability in the extractives sector.

Foreign direct investment. Investments by foreign citizens in stocks and ownership of businesses.

Gross capital formation. Private and public investment in fixed assets, changes in inventories, and net acquisitions of valuables.

Gross domestic product. Total goods produced and services offered in a country for a given year. Usually an indicator of a country wealth.

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries’ (HIPC) Initiative. An arrangement created by the World Bank to cover low-income countries with severe debt.

International Development Association. Aims to reduce poverty by providing interest-free credits and grants for programs that boost economic growth, reduce inequalities, and improve people’s living conditions. It was established in 1960 as part of the World Bank.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). An organization of 186 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world.

Millennium Development Goals. A set of eight goals adopted by world leaders in September 2000 to commit nations to a new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty by 2015.

Official Development Assistance (ODA). Disbursements of loans made on concessional terms and grants by developed countries and donor agencies to promote economic development and welfare in countries and territories in developing countries.

Paris Declaration. Resulted from the decision by donor countries and development partners to undertake far-reaching and monitorable actions to reform delivery and management of aid so as to improve its effectiveness in recipient countries.

Remittances. Transfers of funds back to their home country by migrants who are employed or intend to remain employed for more than a year in another economy in which they are considered residents.

Trade deficit. Difference between imports and exports. Most African countries import more than they export.

Unemployment. The share of the labor force that is without work but available for and seeking employment.

World Bank. Institution was created in 1944 to facilitate postwar reconstruction; over the years its mission has evolved to global poverty alleviation.

1. Unless otherwise noted, all data are drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators Database or related publications for various years.

2. Available at http://aprm-au.org/mission.

UNHCR Statistical Online Database. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available at www.unhcr.org/statistics/populationdatabase. Data extracted August 5, 2012.

World Bank. 2005. Global Monitoring Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

———. 2008. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2008. Washington, DC: World Bank.

———. 2012. Doing Business Report. Available at www.doingbusiness.org/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2012.

Freedom House. 2009. Freedom in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Freedom House. Available at www.freedomhouse.org/uploads/special_report/77.pdf.

Hart, Jeffrey A., and Joan E. Spiro. 1997. The Politics of International Economic Relations. 5th ed. New York: St. Martin’s.

Levy, Brian. 2006. “Governance and Economic Development in Africa: Meeting the Challenge of Capacity Building.” In Building State Capacity in Africa, ed. Brian Levy and Sahr Kpundeh, 1–42. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Puddington, Arch. 2012. “Essay: The Arab Uprisings and Their Global Repercussions.” In Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2012. Available at www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2012/essay-arab-uprisings-and-their-global-repercussions.

Wikipedia. 2012. “African Peer Review Mechanism.” Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_Peer_Review_Mechanism.