During the summer of 2010 I visited my friend Brett in Alabama. We met in high school, but became better friends after I graduated from West Point. On the first day of my visit, he and his friends wanted to go out drinking that evening. Although I don’t drink alcohol, I decided to be social and join them. It was a relaxing and uneventful evening, until they decided to go to a Waffle House at 2:00 a.m.

We were sitting at a table, waiting to order our food. I was probably the only customer in the restaurant who had not consumed alcohol that evening. In the corner, a man who had just received his food was yelling at a waitress because his fork was dirty. He was drunk, and when she did not have a clean fork ready for him immediately, he stood up and walked toward my table. Seeing that I was still holding the menu and had not yet ordered, he took my fork. Another waitress saw what happened and quickly replaced the fork he took from me.

Brett’s friend John was sitting next to me. Angered by the disrespectful behavior of the person who took my fork, he said, “That guy took your fork! Are you going to put up with that?”

I replied, “No harm was done. Now he has a fork. I have a fork. Everybody has forks.”

The more John thought about it, the angrier he got. “You can’t let him get away with taking your fork. I don’t care if he sat down at a table with a dirty fork. It still doesn’t give him a right to take something from you.”

I said, “You have a point, and if he wasn’t drunk I would consider confronting him about taking my fork. But it’s difficult to reason with people when they’re that drunk. People also make bad decisions when they’re drunk, so let’s give him the benefit of the doubt. Maybe he’s nicer when he’s sober. Also, it’s not like he took my wallet. Now everybody has forks and everything is fine.”

The more John thought about the way I had been disrespected, the angrier he got. As I looked at his body language, I could tell his temper was boiling. “I appreciate you wanting to defend my honor,” I said jokingly, “But it’s not worth getting in a fight over. Let’s not worry about it.”

But after seething with anger for several minutes, he finally said, “I’m not going to take this.” Enraged, he walked over to the guy who took my fork and yelled, “He’s a veteran! You can’t take his fork!”

John pointed a hostile finger in the guy’s face, who looked up from his food and began yelling back. The situation was quickly escalating toward a fight, and because I wasn’t drunk I was able to look at the growing chaos with a clear head. First of all, the guy who took my fork was physically massive. He had a friend sitting next to him with a big chain around his neck. They had two other friends with them who were about six foot four, muscular, and wearing cowboy boots, cut-off “daisy-duke” jeans, tank tops, and women’s wigs.

Martial arts training taught me that size does not accurately reflect how tough people are or how well they can fight. Nevertheless, this was not the kind of group I wanted to get in a fight with. Along with the legal risk of being arrested, sued, or imprisoned if someone got seriously injured, was it worth getting hurt or killed over a fork?

I also did not want John to get hurt, and if he were attacked I would have to jump in to help him. So I quickly stood up and tried to deescalate the situation. John yelled louder and louder. The guy who took my fork shouted back and became very aggressive. One of his friends yelled at John, “Shut up and get the fuck out of here!”

John would not back down, so I spoke directly to the guy who took my fork. I said, “We’re not trying to be disrespectful. He’s upset you took my fork, but I just want us to drop it.” By that time a whole bunch of people were shouting and I could barely hear myself talk. I started to feel a little nervous and afraid. That was a good sign, I thought, because it meant I was not feeling fearless and invincible. It meant I had not gone berserk.

My memories of what happened next are vague, perhaps due to the chaos and commotion, but I remember trying to cut through the noise to communicate that no disrespect was intended and this wasn’t worth fighting over. Then I grabbed John by the shoulders and pulled him back as he continued to yell.

Later on the guy with the chain around his neck came up to me and apologized. He said, “My friend is normally a nice guy, and he took your fork because he was drunk and pissed off. I apologize for his behavior, and let me pay for your meal to make up for it.”

The reason I tell this story is because a mini-war was almost started just because people felt disrespected. There was no other reason to fight, because everyone had forks. There was also plenty of food for everyone, and nobody’s personal property was taken. Someone could have gotten seriously injured or killed, simply because people felt disrespected.

Why do martial arts teach us to always respect everyone, including our opponents? The reason is because the majority of human conflict comes from people just feeling disrespected. Being respected is something human beings tend to like a lot. In all of human history, I don’t think anyone has ever seriously said, “I hate it when people respect me! I can’t stand it when people respect me!”

The times in my life when I most wanted to punch someone in the face occurred when I felt disrespected. Take a moment to ponder the times when someone most angered you, and the feeling of being disrespected probably had a lot to do with it. Martial arts philosophy focuses on self-defense, and martial arts taught me if we truly want to protect ourselves and others, the first line of defense is not being skilled at punching and kicking, but being skilled at giving respect.

Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. taught us to love everyone, but to many this seems impossible. This ideal is so high that most people do not even bother trying to attain this lofty goal. It is certainly difficult to love everyone, but a much more attainable goal is learning to respect everyone as human beings. That is a first step we can all strive toward. Not only will respecting everyone as human beings help us wage peace, but respect is the foundation for every genuine act of love, compassion, and kindness. In a television interview I saw many years ago, Jet Li, a famous martial artist, said, “I have the best martial arts self-defense technique. The best martial arts self-defense technique is to smile at people, because if you smile and treat people with respect and kindness, they usually don’t want to fight you. Anyone who gets in a lot of fights has very poor martial arts self-defense” (paraphrased).

Every culture has different standards of respect. For example, in the military and many Asian cultures, being late is extremely rude, and showing up early is a sign of respect. In the army I heard a saying, “If you’re early you’re on time. If you’re on time you’re late.” Since living in California, I have noticed that many people here do not consider it rude to show up a few minutes late. If someone is used to being late, their tardiness might greatly offend someone who served in the military or grew up in an Asian culture. Since respect varies from culture to culture, how can we prevent unintended incidents of disrespect?

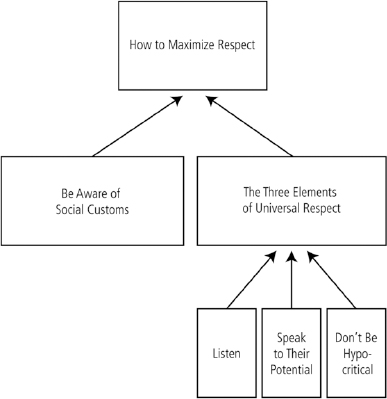

Realizing how dangerous disrespect can be, becoming skilled at giving respect is one of the most effective and essential methods of waging peace. There are two important steps for maximizing the respect we give to others. The first is to not be ignorant of their culture and make an effort to educate ourselves about their social customs. To quote the old adage, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” This means that when you are visiting another culture, it is important to be aware of their social customs and abide by their traditions when it is appropriate.

For example, in the army I was given cultural awareness classes about how to interact with people in the Middle East. I was taught to never show them the bottom of my shoes, never shake with my left hand, and always take off my sunglasses when speaking with people. The army taught me that in the Middle East it is rude to talk to someone while our eyes are covered, because so much of our humanity and trustworthiness is expressed through our eyes. In fact, we actually smile with our eyes, not just our mouth. A genuine smile occurs when the muscles around our eyes flex; if a person’s mouth smiles while the muscles around their eyes remain still it is a clear sign of a fake smile.

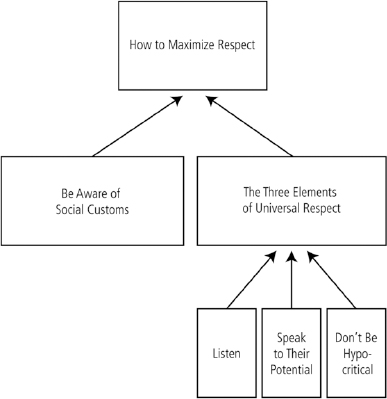

The second step is to practice the three elements of universal respect. The three elements transcend cultures and convey respect in any society. Furthermore, they do not honor people because of their status, but instead give everyone basic human respect, from the richest king to the poorest peasant.

Figure 3.1 How to Maximize Respect

In all of human history, I don’t think anyone has ever seriously said, “I hate it when people listen to me! I can’t stand it when people listen to me!” Everyone likes to be listened to, and in the army I learned that listening is one of the greatest gifts we can give to people.

When I was promoted to captain I was transferred to a new unit, and things started to go badly during the first week. Because I had just joined the unit, they had not added me to their phone roster. As a result, when they called everyone in the unit at 4:00 a.m., ordering us to come in immediately for a surprise drug test, I never received the call. I did not find out about the drug test until I showed up to work later that morning.

When I came to work and started walking down the hall, I heard a colonel screaming and cursing as he told my supervisor what I had done. “I know Captain Chappell just showed up to the unit, but I can already tell he’s a bad officer! He doesn’t think he needs to show up to a drug test, and he just wants to do whatever he wants to do!” I tried to walk into the office to explain that I did not receive a phone call notifying me about the drug test, but the colonel yelled at me, ordering me to get out and wait in the hallway. The screaming and cursing seemed to go on for a long time as I waited. I felt helpless because I was unable to defend myself by explaining what had really happened.

I had just met my supervisor, only working with him for a couple of days. He knew almost nothing about me, and now a colonel was telling him all these bad things about me that were untrue. Soon after the colonel left, my supervisor asked to speak with me. I was nervous, because the colonel not only outranked me, but my supervisor had known him a lot longer than he had known me. Realizing that my supervisor probably had a bad impression of me based on what he had just heard, I tried to defend myself by saying that the colonel’s anger had resulted from a misunderstanding.

But my supervisor interrupted me, saying, “I don’t care what he said. He can yell all he wants, and I will just sit quietly and listen until he is done. I let him yell for so long because I know that if you let people vent and listen to them, they will eventually run out of steam and usually feel better. As for you, I won’t make any judgments about you until I have heard your side of the story. As your supervisor I have a responsibility to at least hear your side of the story and give you the benefit of the doubt before condemning you.”

I explained what happened and he completely understood, and I cannot express in words how wonderful it felt to be listened to and given the benefit of the doubt. Since then I have thought about the many conflicts that could be prevented and resolved if people simply learned how to listen. This is not easy, because listening is a challenging art form. Just as people work hard to become masters in the art of painting, music, or sculpting, it takes effort and commitment to become masters in the art of listening.

How can we listen deeply? How can we absorb what people say as soil absorbs the rain? To truly listen we must develop empathy. If we do not empathize with people we cannot really hear what they are saying. When we do not listen with empathy we hear only their words. But when we listen with empathy we also hear their emotions, hopes, and fears. We hear their humanity.

When we do not listen with empathy our conversations often become barriers that alienate us from the humanity of others. But when we listen with empathy our conversations become bridges that connect their humanity to ours. The art of listening is an essential life skill that can improve our friendships, relationships, and daily interactions with all kinds of people. Listening is also vital for effectively waging peace. Take a moment to think about a controversial issue that matters a lot to you. Now imagine discussing that issue with someone who passionately disagrees with you. Would you feel comfortable having a conversation with that person? Most people would feel uncomfortable and worry about the conversation devolving into a shouting match, but the art of listening transforms the blank canvas of a potentially hostile conversation into a masterpiece of possibilities.

Leslee Goodman, who interviewed me in the Sun magazine, explains how I was able to change the attitude of an adamant pro-war supporter:

Chappell teaches through example. I met him at a weekly peace vigil on a downtown Santa Barbara, California, street corner, where he demonstrated how to engage even strident opponents with empathy and respect. I had lost patience with one such person after ten minutes of unproductive dialogue. Then Chappell showed up. He respectfully engaged my critic for a full forty-five minutes. Their conversation ended with the man thanking Chappell for listening to him and accepting a copy of [his book] The End of War. A few weeks later Chappell ran into the man and learned that he had read the book and had changed his mind about war as a means of ending terrorism.

Martial arts taught me that even the best techniques are never 100 percent effective. In ideal circumstances the best techniques would succeed every time, but the circumstances we must work in are usually less than ideal. In a similar way, listening is an important technique that makes genuine dialogue possible, but sometimes a person is so stubborn and has so many biases that our best efforts do not succeed.

Singer Harry Belafonte, a friend of Martin Luther King Jr., describes how King was unable to convince a group of young African Americans to embrace the nonviolent methods of the civil rights movement. Noticing King’s sadness, Belafonte asked him, “What troubles you, Martin?” King replied, “Well, I just came from that meeting with the young people in Newark and they said much that challenged me. They made great justification for why they saw violence as an important tool to their liberation. My task was to take the truths that they were experiencing, the pain they were experiencing, and say there is another way. When I left, I felt that I had not convinced them, that I had not gotten to them in the way which I would have loved to have gotten to them.”1

Not even Martin Luther King Jr.—a black belt in waging peace—succeeded in persuading people 100 percent of the time. Although martial arts taught me that even the best techniques do not work every single time, I also learned that we can dramatically improve the success rate of our techniques. When I first tried to speak about peace in my early twenties, all I knew was how to preach to the choir. When I spoke to ten people who opposed my views on peace, I communicated in such a counterproductive way that I only persuaded one out of ten if I was lucky, and I probably alienated and offended the other nine due to the careless way I interacted with them.

As I learned the art of listening and grew more skilled at the other techniques of waging peace, I became empowered to do more than preach to the choir. This allowed me to persuade perhaps three out of ten who opposed my views on peace, and although the other seven might not agree with me, I was doing less to alienate and offend them. Today I think I can persuade perhaps six or seven out of ten, and I now speak in such a way that I alienate and offend far fewer people than I did before.

It is impossible to persuade or please everyone. At West Point I had a roommate who did not like chocolate. If chocolate cannot please everyone, how can any of us? Even Martin Luther King Jr. was hated by many despite his best efforts. But unlike some activists I have met, King did not want to just preach to the choir or alienate those who disagreed with him. He wanted to go beyond the choir by persuading as many as possible and alienating as few as possible. All social problems come from how people think, and all progress comes from transforming how people think. In a later chapter I will explain why we don’t have to convince every single person for progress to happen. We just have to convince enough people, and the techniques of waging peace can help us persuade more and alienate less.

The first step is listening. If all you do is listen deeply when people passionately disagree with you about a controversial issue, that can be an important victory. Listening allows you to connect with their humanity, better understand where they are coming from and why they think the way they do, and gain insights into how you can more effectively reach them.

Listening also has the potential to make a strong impression on the people you are listening to. We live in a society where people seldom listen to each other, and when I watch television I see countless pundits and politicians who are disrespectful to each other and unwilling to listen. When you possess the rare ability to listen deeply, someone might walk away from a conversation with you, thinking, “I don’t see eye to eye with those peace activists, but they sure are kind and really good listeners. I can’t remember the last time someone really listened to me. My boss doesn’t listen to me. My coworkers don’t listen to me. I often feel like my wife (or husband) isn’t even listening to me.”

By listening deeply we plant a seed of change. Perhaps the seed will sprout long after the conversation has ended, causing the person to think about what you said and allowing your ideas to sink in. This might help the person develop a more positive attitude toward peace activists and become more open to future discussions about peace. Or maybe the seed will lie dormant and never significantly impact the person’s way of thinking. People must choose to let peace bloom within them. But the more seeds of change we plant in people from all walks of life, the larger the potential harvest.

For many years I viewed respect as a delicious meal, but its ingredients remained a secret. Just as a person can taste a flavorful soup and not know all of its ingredients, I had tasted respect but could not pinpoint exactly what was in it. If you had to summarize in words what makes someone respectful and another person disrespectful, how would you describe it? Is it their tone of voice, choice of words, or body language? It can be very difficult to capture the subtle differences between respect and disrespect in a few words, but then I had a deeper realization.

As I thought about all the times throughout my life when people spoke to me respectfully, they always talked to me as if deep down I was a good person, even if I was behaving badly. Martin Luther King Jr. referred to those who wanted to kill him as “our sick white brothers,” recognizing that the white racists who wanted him dead were ill with hatred, but still his brothers. When people are disrespectful they talk to us as if we lack goodness, dignity, or worth as human beings. Disrespect makes us feel worthless, while respect recognizes our enormous human potential.

Human beings have the potential to live with integrity, reason, compassion, and conscience. However, not everyone lives up to their human potential. When we talk to people in a respectful way we must “speak to their potential” by speaking to their integrity, reason, compassion, and conscience. We must strive to communicate with and stimulate those parts of their humanity. Being respectful does not mean naively pretending that every person lives with these virtues. Instead, being respectful is a way to remind people of what it means to be fully human.

When soldiers make small, careless mistakes in the army, an example of not speaking to their potential would be, “Why are you so stupid? You are such an idiot!” On the other hand, an example of speaking to their potential would be, “Why did you do that? You know better, and because I have seen how well you can perform, I expect a lot out of you. Now what are you going to do to ensure that this doesn’t happen again?” A quote attributed to the German poet Wolfgang von Goethe says, “If we treat people as they ought to be, we help them become what they are capable of becoming.”

Some people view respect as naive and impractical in the real world, but this could not be further from the truth. Martial arts philosophy teaches that respect is vital for self-defense, and Gandhi, King, and Mandela harnessed the power of respect to advance their causes in extremely difficult circumstances. Christo Brand started working at Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned, in 1978. Brand was an unquestioningly proapartheid eighteen-year-old white prison guard. Despite their differences in race, age, and political views, Mandela respected the young prison guard. Brand explained how this affected him: “When I came to the prison, Nelson Mandela was already 60. He was down-to-earth and courteous. He treated me with respect and my respect for him grew. After a while, even though he was a prisoner, a friendship grew.”2

Brand started doing favors for Mandela, smuggling in bread and bringing him messages. He also broke the rules in order to let Mandela hold his infant grandson.3 But as Brand explains, Mandela seemed more concerned about the well-being of the young prison guard than the favors he was receiving: “Mandela was worried that I would get caught and be punished. He wrote to my wife telling her that I must continue my studies. Even as a prisoner he was encouraging a warder to study.”4 If Mandela could have such an influential impact on his white pro-apartheid prison guard, think of the many ways respect can bridge the divides that separate us.

For those who still think respect is naive and impractical in the real world, we should remind them of an important fact. When people in a community respect each other as human beings, the bonds between them become stronger, empowering them to overcome significant challenges. At West Point every freshman has to memorize a passage from a speech Major General John M. Schofield gave there in 1879. The passage, which explains the practical value of respect, reads: “The discipline which makes the soldiers of a free country reliable in battle is not to be gained by harsh or tyrannical treatment. On the contrary, such treatment is far more likely to destroy than to make an army . . . He who feels the respect which is due to others cannot fail to inspire in them regard for himself, while he who feels, and hence manifests, disrespect toward others, especially his inferiors, cannot fail to inspire hatred against himself.”5

West Point taught me that one of the most powerful leadership principles is leading by example. What does it mean to lead by example? In his book Legacy of Love, Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, tells a story about his grandfather that illustrates what it means to lead by example:

I became friends with a boy named Anil, who was my age. Anil had a weakness for sweets that verged on obsession. He consumed more than was good for him. One day he became ill, and his parents took him to the doctor. The doctor’s advice was that Anil must drastically reduce the amount of sweets that he consumed. Anil’s parents tried to enforce the doctor’s orders . . . Both parents would nag Anil about not eating sweets while they themselves continued to eat sweets every day. Several weeks went by and the parents found that Anil was continuing to eat sweets when no one was looking. They brought him to Grandfather [Mahatma Gandhi] with an appeal to drum some sense into him.

“Anil will not listen to us,” his mother told Grandfather. “The doctor has said he should not eat any sweets, but he still consumes them on the sly. He refuses to obey us. Please speak to him.”

Grandfather heard the complaint patiently, and just as patiently told Anil’s mother, “Come back with Anil after fifteen days.”

Anil’s mother was perplexed. All she believed Grandfather had to do was tell the boy not to eat sweets. They were bad for him. Why did she have to wait for fifteen days? She could not fathom this, but she was not prepared to argue with Grandfather.

On the fifteenth day she returned. Grandfather took Anil aside and whispered into his ear. Anil’s eyes sparkled. Grandfather asked him for a high five to seal their private deal, and they left.

Anil’s mother had no idea what had transpired, but she was skeptical. A few days later both parents came back to Grandfather utterly amazed and asked him, “How could Anil obey you so readily, and not us? Tell us the secret.”

Grandfather explained, “It was no miracle. I asked you to come back after fifteen days because I had to first give up eating sweets before I could ask him to do so. I simply told Anil that I had not eaten sweets for fifteen days, and that I would not eat any until the doctor allowed Anil to eat sweets.”

It was a simple lesson in the power of correcting by example, but how many of us practice this? We are quick to use our authority or superior physical strength to force others to do what we want them to do, and as a result, even if we are obeyed, we have not effected the kind of change that makes our lessons permanent.6

Hypocrisy occurs when we do not practice what we preach. Recognizing how dangerous hypocrisy is to the health of any military unit, the army encourages its soldiers to “lead by example.” The army’s Drill Sergeant Creed states: “I will lead by example, never requiring a soldier to attempt any task I would not do myself.” By not asking Anil to stop eating sweets unless he did so first, Gandhi led by example.

Not only do Gandhi and the army both condemn hypocrisy. So did Jesus, saying, “Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye? How can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when all the time there is a plank in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.”7

If a person you admire who has enormous integrity gives you advice on being honest, it can be accepted with a feeling of mutual respect. But if a dishonest person lectures you on honesty it comes across as disrespectful and can make your temper boil. Few things make us angrier than hypocrisy. That is why being respectful not only involves listening and speaking to someone’s potential, but also looking at our own behavior to ensure we are not being hypocritical. We can listen and speak to someone’s potential all day long, but our words will sound disrespectful if we don’t first practice what we preach.

The army taught me that respect is my shield. No matter how disrespectful someone is to me, responding in a respectful way serves as a shield by allowing me to maintain my moral authority. As soon as I become disrespectful I lose my moral authority, which is my true power base as a leader. To support this idea, the army taught me that the best leaders seldom have to rely on rank, because the moral authority they gain through giving respect and leading by example is so strong that many soldiers will follow them out of admiration. Gandhi showed how influential moral authority can be. He led 390 million people on the path to freedom, yet he was not a general or a president and had no official power. Martin Luther King Jr. said this was one of the most significant things that ever happened in world history.

I call respect the infinite shield, because it not only protects us but everyone around us. It prevents dangerous situations from escalating and serves as a first line of defense against violence. Another reason I use the word “infinite” to describe the shield of respect is because we cannot truly measure where it ends. It can extend beyond our local community. It can even extend far into the future. A husband and wife who treat each other with respect will make a positive impression on their children, passing the shield of respect on to future generations. Like the ripples that emanate from a pebble dropped in a pond, the respect we give to others ripples out into the world and through the ocean of time.

The infinite shield is only the first line of defense. It is not impenetrable and can be breached, as it was when King was assassinated. Accordingly, we must have a second, third, and even fourth line of defense as backups when people break through the infinite shield. Before I describe the other lines of defense later in this book, let us not underestimate the power of the infinite shield as a first line of defense. When we bring the infinite shield into any room we create a safer environment for everyone in that room. The more people around the world who embrace the infinite shield, the safer our world will be.

Although King was assassinated, I and countless others have better lives today because he respected the white people who opposed him. By embracing the infinite shield, he helped prevent a race war that nearly erupted as tensions mounted during the civil rights era. While imprisoned in a Birmingham, Alabama, jail for conducting a peaceful protest in 1963, he wrote: “If this [peaceful] philosophy had not emerged, by now many streets of the South would, I am convinced, be flowing with blood . . . If [African Americans’] repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history. So I have not said to my people: ‘Get rid of your discontent.’ Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action.”8

Respect is an infinite shield that can help us protect ourselves and those around us. As I will discuss later in this book, the infinite shield can also help us protect our country and planet in the twenty-first century. When we learn how to wield the infinite shield with the skill of a peace warrior, however, it offers more benefits than just protection. The ability to convey respect improves our relationships with other people, and it unlocks many of our human powers such as empathy, love, and calm.