To create societal change we don’t have to convince every single person that a cause is justified, fair, and reasonable. We only have to convince enough people. For example, was every single man in America convinced women should have the right to vote? No, and there are still men in America who don’t think women should have the right to vote. Was every single white person in America convinced slavery and segregation should go away? No, and there are still white people in America who want slavery and segregation to come back.

When any form of positive change is concerned, it is impossible to convince everyone it should happen. As I explain in Peaceful Revolution, many people have not developed their empathy, conscience, reason, and the other muscles of our humanity that encourage us to work for positive change. And as I explain in The End of War, the human brain is the most complex thing we know of in the universe, and our extremely complex brains make us vulnerable to a wide variety of mental disorders that can inhibit our empathy, conscience, and reason.

During my lectures around the country I often talk to diverse groups. When I speak with a group of fifty people and mention how the women’s rights movement greatly inspires me, I realize there might be one or two people in the audience who wish women never gained the right to vote. Two out of fifty is only 4 percent of the audience. That might seem like a tiny percentage, but what if 4 percent of the American population believed women should not have the right to vote? How many would that be? As I write this the American population is around 300 million, and 4 percent of that is a whopping 12 million. In fact, if just one out of every thousand Americans believed women should not have the right to vote, that would still be 300,000.

Many people today who oppose women’s and civil rights would never say it in public, because women’s and civil rights have now become social norms. What is a social norm, and how does it work? A social norm occurs when a new idea has persuaded enough people to create a new public consensus. To better understand this, imagine a white man who works in a typical office in America—one that has women and people of various racial backgrounds. Now imagine him standing up and yelling, “No woman should be allowed to vote! All niggers should be slaves!” He would not only alienate the women and African Americans in his office, but also most of his white male coworkers because our society has begun to view racists and sexists as ignorant, closed-minded, and hateful. In addition to alienating his coworkers, he would probably get fired and might even get beaten up.

Now imagine if two hundred years ago in America someone shouted in public, “No woman should be allowed to vote! All niggers should be slaves!” This statement would have received little opposition and a lot of applause, because the modern social norms of women’s and civil rights did not exist back then. To understand how influential social norms are, do you know what President George W. Bush considers the worst moment of his presidency? Was it when our country was attacked on September 11? Was it when the torture committed by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq was exposed? Was it when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and other cities? No. President Bush said the worst moment of his presidency was when rapper Kanye West called him a racist. President Bush explains:

At an NBC telethon to raise money for Katrina victims, rapper Kanye West told a primetime TV audience, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people . . . ” Five years later, I can barely write those words without feeling disgusted . . . The more I thought about it, the angrier I felt. I was raised to believe that racism was one of the greatest evils in society. I admired Dad’s courage when he defied near-universal opposition from his constituents to vote for the Open Housing Bill of 1968. I was proud to have earned more black votes than any Republican governor in Texas history. I had appointed African Americans to top government positions, including the first black woman national security advisor and the first two black secretaries of state . . . The suggestion that I was a racist because of the response to Katrina represented an all-time low. I told Laura at the time that it was the worst moment of my presidency. I feel the same way today.1

I am including this story from President Bush for one reason only: to illustrate how the worst thing we can call somebody today is a racist. Several hundred years ago the idea of being a racist didn’t really exist. Imagine if time travel were possible and you went back to the eighteenth century. If you called a white person back then a racist, he would likely ask, “What does that mean?” If you said, “It means you think all white people are superior to black people just because they’re white,” he would probably reply, “Of course we’re superior to black people! We’re white!” Today the public consensus toward racism has changed, and it is simply not cool to openly be a racist anymore.

Because calling someone a racist is such a serious insult in modern America, many people today do not realize that the concept of racism appeared relatively recently in history. In their book Racism, Robert Miles and Malcolm Brown say, “Although the word ‘racism’ is now widely used in common-sense, political and academic discourse, readers may be surprised to learn that it is of very recent origin. There is no reference to the word in the Oxford English Dictionary of 1910 (although there are entries for ‘race’ and ‘racial’) . . . The OED Supplement of 1982 . . . records its first appearance in the English language in the 1930s.”2

I am certainly not saying racism and sexism in America have vanished. Instead, I am saying these societal ills are different than they used to be. The new social norms of women’s and civil rights have reduced the power of overt racism and sexism in America, but as a consequence the forms of racism and sexism that continue to persist have become more covert. Two hundred years ago racism was most dangerous in the daylight, like a massive army that intimidates by showing off its numerous soldiers with their sharpened spears shining beneath the sun. Racism back then gained immense public support and legal protection for the enslavement and brutal treatment of an entire race, and through sheer intimidation in the public sphere the slavery system could not only make slaves afraid to run away, but also frighten conscientious white people who wanted to oppose slavery.

Today racism is most dangerous under the cover of night, like an assassin hiding in the darkness. Racism today is not powerful because of its ability to intimidate people in the public sphere but because of its stealth. Racism today is most dangerous when we do not realize it is there, or when we make the kind of hyperbolic statements that cause people to not take us seriously, such as saying African Americans are no better off today than they were two hundred years ago.

There are still some overt forms of racism in America today, such as the prejudice against people of Middle Eastern descent. And although I use African Americans as an example of racism in America’s past, many groups in America have also been subjected to racism, such as Native Americans, Asians, Hispanics, Jews, Italians, and even groups of white people such as the Irish. Many people today incorrectly assume that only those with darker skin tones have suffered from racism, but Eugene McLaughlin explains how the Irish were also treated as racially inferior subhumans:

In both Britain and North America the Irish endured anti-Catholic hostility and were accused of taking jobs, undercutting wages, creating slums, and being political troublemakers. Anti-Irish cartoons in magazines such as Punch, supported by respectable writers such as Charles Kingsley, Thomas Carlyle and Elizabeth Gaskell, depicted them as being a less evolutionarily developed race. Kingsley stated that, “to see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black, one would not feel it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours.” [After visiting the United States in 1881, Oxford professor] Edward A. Freeman commented that “This would be a grand country if only every Irishman would kill a Negro and be hanged for it.” It is in this context of Irishophobia that the racist caricature of the unpredictable, drunken, violent, ignorant “Paddy” was established. Their supposed wildness meant that writers questioned whether the Irish could ever be assimilated into civilized society. Anti-Irish riots occurred in many towns in Britain and the USA during the nineteenth century.3

As the first two lines of defense against injustice and violence, the infinite shield and the sword that heals attack hatred and ignorance at their root by transforming how people think for the better. This has reduced racism and sexism in America, and waging peace gives us the means to continue winning battles against these and other forms of injustice. In order to win these battles, waging peace empowers us to create societal, spiritual, and ideological change on a personal, national, and global level.

Although the infinite shield and the sword that heals are very effective at transforming how people think, deflection is a third line of defense that is useful whenever hatred is able to breach the shield and dodge the sword. Why do I use the word “deflection?” Unlike the infinite shield and the sword that heals, deflection does not directly confront the underlying causes of people’s hatred. Instead, deflection misdirects their hatred by giving them other concerns to think about, such as the serious consequences that might result if they decide to turn their hostile thoughts into hostile actions. This can deflect unjust and violent acts, just as martial artists use evasive techniques to deflect attacks.

Social norms are the first form of deflection, but sometimes not even the most entrenched social norms can dissuade a hostile person with violent intentions from committing an unjust act. This is why we need laws, which are the second form of deflection. Martin Luther King Jr. used the infinite shield and the sword that heals to dramatically transform how people think for the better, yet he never underestimated the need for laws. He also realized that every large society must have a way of enforcing its laws, which he called “the intelligent use of police force.”

When the Supreme Court Case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional, the attempt to integrate black and white students at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, was met with heavy resistance. In addition to a mob that tried to prevent nine black students, who became known as the “Little Rock Nine,” from entering the school, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus decided to use armed National Guard soldiers to keep the black students out. Journalist David Margolick describes what happened:

In the fall of 1957, [fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford] was among the nine black students who had enlisted, then been selected, to enter Little Rock Central High School. Central was the first high school in a major southern city set to be desegregated since the United States Supreme Court had ruled three years earlier in Brown vs Board of Education that separate and ostensibly equal education was unconstitutional . . . Lots of white people lined Park Street as Elizabeth headed towards the school. As she passed the Mobil station and came nearer, she could see the white students filtering unimpeded past the soldiers. To her, it was a sign that everything was all right. But as she herself approached, three Guardsmen, two with rifles, held out their arms, directing her to her left, to the far side of Park. A crowd had started to form behind Elizabeth, and her knees began to shake . . .

She steadied herself, then walked up to another soldier. He didn’t move. When she tried to squeeze past him, he raised his carbine. Other soldiers moved over to assist him. When she tried to get in around them, they moved to block her way. They glared at her. Now, as Elizabeth continued walking south down Park, more and more of the people lining the street fell in behind her. Some were Central students, others adults. They started shouting at her. The primitive television cameras, for all their bulkiness, had no sound equipment. But the reporters on the scene scribbled down what they heard: “Lynch her! Lynch her!” “No nigger bitch is going to get in our school!” “Go home, nigger!” Looking for a friendly face, Elizabeth turned to an old white woman. The woman spat on her.4

As the mob threatened to lynch the black students, the NAACP kept them home for several weeks due to safety concerns. A court ordered Governor Faubus to withdraw his National Guard soldiers who were preventing the integration of the school. He complied. The Little Rock Nine returned to school on September 23, but outside the building local police tried to control at least a thousand angry white segregationists. When the mob threatened to storm the school, the police took the children out a back door. The mob beat up several black journalists, including a World War II combat veteran.5

In response, President Eisenhower sent federal soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock. The armed soldiers arrived by dawn the next day, escorting the nine black students through the front door and into their classrooms. The federal soldiers remained at the school throughout the year, but were unable to protect the students from all acts of violence. Elizabeth Eckford was pushed down a flight of stairs, and the three black male students had to deal with physical assaults.6 During a television interview later that year, Martin Luther King Jr. was asked how he could advocate nonviolence, yet support the use of armed federal soldiers to integrate a school. He replied:

I think it is quite regrettable and unfortunate that young high school students have to go to school under the protection of federal troops, but I think it is even more unfortunate that a public official, through irresponsible actions, leaves the President of the United States with no other alternative. So I did back [President Eisenhower] and I sent him a telegram commending him. Now your main question is . . . how does this jibe with my whole philosophy of nonviolence? I believe firmly in nonviolence as I have already said, but at the same time I am not an anarchist. Now some pacifists are anarchists following Tolstoy, but I don’t go that far. I believe in the intelligent use of police force. I think one who believes in nonviolence must recognize the dimensions of evil within human nature, and there is a danger that one can indulge in a sort of superficial optimism thinking man is all good. Man does not only have the greater capacity for goodness, but there is also the potential for evil. And I think of that throughout my whole philosophy and I try to be realistic at that point. So I believe in the intelligent use of police force, and I think that is all we have in Little Rock. It’s not an army fighting against a nation or a race of people. It is just police force, seeking to enforce the law of the land.7

When King said he supported “the intelligent use of police force,” he realized law enforcement officers can use many techniques other than killing to keep us safe. To mention a few examples, law enforcement officers stopped terrorists such as Ted Kaczynski (the “Unabomber”) and Timothy McVeigh, along with numerous serial killers, without killing a single person. The police have the ability to conduct investigations and arrest people, who are then supposed to receive a public trial by a jury of their peers.

However, King was not naive about abuses committed by the police, and as a black man living under segregation in the South he saw firsthand how law enforcement officers can be used for evil. He often felt threatened by police officers in the South. As I mentioned earlier, before the Civil War federal marshals had been legally required to return escaped slaves to their slave masters. But King realized the behavior of law enforcement officers reflected the society they were protecting, and he wanted to shape social norms and laws in a way that would allow the police to do more good than harm. Waging peace gives us the power to defeat the social norms and laws that are unjust, and create ones that are just.

Social norms and laws deflect violent and unjust behavior by making people consider the consequences. This can deter them from turning their hostile intentions into hostile actions, because the consequences could include public ridicule, harm to one’s career and reputation, physical injury, being arrested, and going to jail. Unlike deflection, however, the infinite shield and the sword that heals do not deter people from turning their hostile intentions into hostile actions. Instead, these forms of waging peace strive to transform their hostile intentions into understanding and compassion. King believed that many white people in the South were good while many more had the potential for goodness. To unlock their vast potential for goodness, King thought Jesus was wise when he commanded us to “love our enemies.” King said, “Love is the only force capable of transforming an enemy into a friend.”8

Although I experienced some racism in Alabama, I am proud to be from Alabama for many reasons. To help me survive in the dangerous world he knew, my father taught me to think like him and previous generations of African Americans who lived in terror, yet a lot has changed since he grew up during segregation and the days when his father was raised by former slaves. Whenever I return to visit the South, I can see how far it has come since my father grew up during segregation, and I am proud of the progress it has made. King showed that hostile intentions could in fact be transformed into understanding and compassion, because today in Alabama there are many more people who treat African Americans as human beings rather than subhumans.

Nevertheless, there are still some people in Alabama and other states who want to kill human beings because of the color of their skin, so I am glad we have laws. Waging peace does not seek to demonize these or any other people, but to understand them. Later in this book I will explore the depths of human nature to explain why new ideas are often met with so much hostility.

Sometimes people are so determined to murder someone that even social norms and laws cannot deter them. When people are willing to break the law to commit violence, a third form of deflection is available. Before I can discuss what it is, however, I must first discuss the differences between waging war and waging peace.

Waging war and waging peace have a lot in common. They both require courage, commitment, determination, teamwork, discipline, camaraderie, strategic thinking, selflessness, sacrifice, and many more similarities. But there are two major differences between waging war and waging peace. The first is the use of violence. Waging war tries to turn the human beings who oppose you into corpses, while waging peace tries to turn the human beings who oppose you into friends. That’s a big difference, but there’s an even bigger difference.

Sun Tzu said it best: “All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.”9 When I studied boxing I learned it is based on deception. If you want to punch your opponent with your left hand, you should trick him into thinking you’re going to punch him with your right hand. The better a boxer is at deceiving his foe, the more easily he can defeat him. Like boxers, the best chess players are also very skilled at using deception to bluff, confuse, bait, and ambush their opponents.

It is unfortunate our society sees the fundamental nature of war as violence, when its fundamental nature is really deception. Sun Tzu taught that the art of war is in many ways the art of deception, and many religions and mythologies acknowledge that deception is a deeper evil than violence. For example, Satan in Christianity, Loki in Nordic mythology, and Mara in Buddhism are not evil because they are masters of brute force and violence, but because they are masters of cunning and deception.

The god of war in Greek mythology is Ares. Just as all war is based on deception, Ares is a liar who is despised by his father Zeus. In the Iliad, Zeus tells Ares he hates him more than any of his other children, and if they were not father and son he would banish the god of war to the bottom of the dark pit where the cursed Titans are imprisoned. Zeus says, “No more, you lying, two-faced . . . I hate you most of all the Olympian gods . . . You have your mother’s uncontrollable rage . . . You are my child [but] to me your mother bore you. If you had sprung from another god, believe me . . . long ago you’d have dropped below the Titans, deep in the dark pit.”10

Waging peace on the other hand is based on the truth, and the art of waging peace is in many ways the art of truth-telling. Some people who believe in moral relativism have told me there is no such thing as truth, but I have evidence that proves otherwise. To offer a couple of examples, it is true that women are not intellectually inferior to men, and it is also true that African Americans are not subhuman. These statements express as much scientific truth as Copernicus and Galileo when they claimed the earth revolves around the sun. The underlying purpose of the women’s rights movement was to expose the truth about women’s equality, and the underlying purpose of the civil rights movement was to expose the truth that African Americans are human beings.

Our most cherished ideals—such as liberty, justice, and fairness—cannot exist without the ideal of truth. Unless our society is built on a foundation of truth-telling, we will never truly have liberty, justice, and fairness. Peace is another ideal that requires the ideal of truth. The war system, on the other hand, requires deception. When a military commander masters the art of deception, he can easily gain the element of surprise in war. This gives any military commander a significant advantage over his opponent, but Gandhi realized waging peace requires us to replace the element of surprise with the element of honesty.

Every effective army in history kept secrets to maintain the element of surprise, and today militaries around the world have extensive top-secret files. But Gandhi did not have any top-secret files, because he knew that peace requires trust, mutual understanding, and transparency. In fact, when he conducted his Salt March to the Sea, a nonviolent protest against the oppressive British salt tax, he sent a letter to the British viceroy, Lord Irwin, telling him exactly what he planned to do. In the letter Gandhi explained why the salt tax was unjust. He then outlined his plan to oppose the tax and invited the viceroy to arrest him. Gandhi said in his letter:

If you cannot see your way to deal with these evils and my letter makes no appeal to your heart, on the 11th day of this month, I shall proceed with such coworkers of the Ashram as I can take, to disregard the provisions of the salt laws. I regard this [salt] tax to be the most iniquitous of all from the poor man’s standpoint. As the [Indian] independence movement is essentially for the poorest in the land the beginning will be made with this evil. The wonder is that we have submitted to the cruel monopoly for so long. It is, I know, open to you to frustrate my design by arresting me. I hope that there will be tens of thousands ready, in a disciplined manner, to take up the work after me . . . This letter is not in any way intended as a threat but it is a simple and sacred duty peremptory on a civil resister.

He ended the letter by saying, “I remain, your sincere friend, M. K. Gandhi.”11 Later in this book I will explain why Gandhi’s approach was so revolutionary from a strategic perspective. Many people today would call Gandhi stupid for telling the viceroy his plan, but later I will explain why Gandhi was more innovative than any general I have ever studied.

If the ideal of truth that Gandhi was loyal to creates the foundation not only for ideals such as liberty, justice, and fairness, but also waging peace itself, is it ever all right to lie in pursuit of peace? To understand why this question is so challenging, take a moment to consider the following moral dilemma. Imagine you were living in Germany during World War II and hiding Jews in your attic. Several Nazi soldiers come to your house, knock on your door, and rigorously question you about the whereabouts of any Jews hiding in the area. Is it all right to lie to them?

This is not a far-fetched hypothetical scenario, because situations similar to this occurred many times during the brutal reign of the Nazis in Germany. According to historian Johannes Tuchel, the head of the German Resistance Memorial Center in Berlin, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Berliners actively hid Jews from Nazis. Tuchel says, “The number of Berlin rescuers might sound impressive at first, but compared to the 4 million who lived in Berlin at the time and didn’t help, 20,000 are not a lot at all.”12

Situations such as this also occurred when the Hutus massacred the Tutsis in Rwanda and conscientious people tried to hide the survivors. This happens wherever there is genocide, and it might be happening somewhere in the world as I write this.

This is not an easy question for some peace activists, because it causes them to question their most cherished ideals, such as the ideal of truth. I know peace activists who are unwilling to lie, even when confronted with the scenario I just presented. One peace activist told me, “Instead of telling them where the Jews were hiding or lying about it, I would try to distract the Nazis by pointing somewhere off in the distance and saying, ‘Look over there!’” I replied, “I don’t think most Nazis were that stupid, and realistically speaking it would probably only make them more suspicious of you.”

The question of when to lie to deflect violence troubled me for a long time, but then a peace activist and peace studies professor named Barbara Wien told me a story that gave me new insights into the question. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, Barbara, who was seven months pregnant at the time, went into a subway station and saw several neo-Nazis bullying an Arab American. They were taunting him with racial slurs, pushing him, and becoming very aggressive. Although the station was mostly empty, Barbara immediately went around and pleaded with the few people waiting for the next subway train. She said, “We have to help him! We have to stop this!”

Nobody wanted to get involved and risk getting hurt, so they turned away or hid their faces behind their newspapers. Unable to recruit any allies and concerned she would not be able to convince the neo-Nazis to back down without the help of others, Barbara needed another plan. She thought about calling 911 because some aggressive people will back down when they realize the police are on the way, but she could not get cell phone reception in the subway tunnel. Just when it seemed like no options were left she suddenly had a radical idea, but in order for it to work she would have to time it just right.

When the next subway train pulled in and the doors opened, she ran up to the Arab American and said, “Mohammed! It’s so great to see you! It’s been so long!” The Arab American and neo-Nazis all had confused looks on their faces. Not giving them time to react, she quickly grabbed the Arab American’s arm and pulled him onto the subway train. As the doors closed, the neo-Nazis suddenly had realized what happened. Enraged, they started pounding on the door and shouting as the subway train began to speed away.

Did you notice what Barbara did? When she called the Arab American “Mohammed” and acted like she knew him, she used deception. She had never met him before and had no clue who he was. Her creative and brilliant plan was an example of the third form of deflection: outsmarting violence.

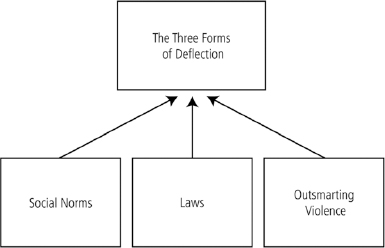

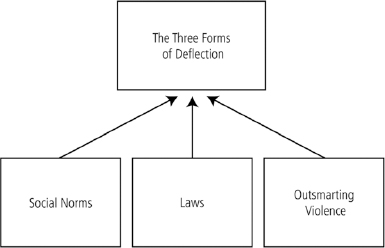

Figure 5.1 The Three Forms of Deflection

Gavin de Becker, widely regarded as the nation’s leading expert on violence prediction and prevention, says that of all human behavior violence is the easiest to predict, because it gives off the most warning signs. His book The Gift of Fear explains how we can recognize the warning signs of violence. He also explains how we can predict and prevent violence, because as human beings we have the ability to outsmart it. There are many ways to outsmart violence, and using deception is one way. If you would like to learn more about how we can outsmart violence, I highly recommend The Gift of Fear.

Barbara was in a situation where the neo-Nazis were so hateful and enraged that the infinite shield and the sword that heals seemed unlikely to work, unless she could recruit allies willing to stand with her. When people refused to join her, she moved onto the third line of defense: deflection. But it is difficult to enforce social norms (the first form of deflection) without the support of others, and laws (the second form of deflection) also seemed unlikely to work because she could not contact the police and the neo-Nazis were so blinded by rage that the consequences of breaking the law did not seem to matter to them. Barbara’s next option was outsmarting violence (the third form of deflection), and it worked.

In a similar way, if Nazis came to your house looking for Jews and the infinite shield, the sword that heals, social norms, and laws could not protect the people you were hiding, another option would be to outsmart violence by telling the Nazis a very convincing lie. Like every technique, outsmarting violence does not always work. If the Nazis were not fooled by your lie, the aftermath could be deadly. Historian Klaus Fischer describes how one Nazi reacted when he realized a woman was withholding information from him: “In one town the Jews had gone into hiding and when the SS swept through the town they discovered a woman with a baby in her arms. When the woman refused to tell them where the Jews were hiding, one SS man grabbed the baby by its legs and smashed its head against a door. Another SS man recalled: ‘It went off with a bang like a bursting motor tire. I shall never forget that sound as long as I live.’”13

The purpose of this chapter is not to tell you what to do in every situation, but to let you know what your options are so that you can make the best decision. Every hostile situation is different, and you must assess the unique circumstances you are in, consider your options, and do what you think will work. When the option of outsmarting violence as a way of deflecting hostile actions is concerned, I must make a crucial point that I cannot emphasize enough. Lying should not be used when waging peace, but only in the rare situations when the infinite shield and the sword that heals seem unlikely to work and deception is needed to protect someone in imminent physical danger. I have seen too many activists tell exaggerated stories and outright lies in order to draw more attention to their cause, rationalizing their deception by saying it’s serving the mission of peace. But as long as we believe we can lie our way to peace, we will never truly achieve peace.

Human memory is not perfect, but we must be committed to honoring the truth the best we can. When we try to wage peace by exaggerating our stories and twisting the facts, we are no longer waging peace. When waging peace in our personal lives, a lot of skill is required to deal with people honestly yet gently and compassionately. Being honest does not give us a license to be rude. In other words, being honest does not give us a right to insult people and disregard their feelings.

Japan’s Code of the Samurai, written over three hundred years ago, emphasizes the importance of balancing truth with tact:

Expressing your opinions to others, or objecting to their views, are also things that should be done with due consideration . . . Anything a warrior says must be tactful and considerate. How much the more so when speaking with friends and colleagues; tact is even more appropriate under those circumstances . . . Once you have become someone’s confidant, it shows a certain degree of dependability to pursue the truth and speak your mind freely even if the other person doesn’t like what you say. If, however, you are fainthearted and fear to speak the truth, lest you cause offense or upset, and thus say whatever is convenient instead of what is right, thereby inducing other people to say things they shouldn’t, or causing them to blunder to their own disadvantage, then you are useless as an advisor.14

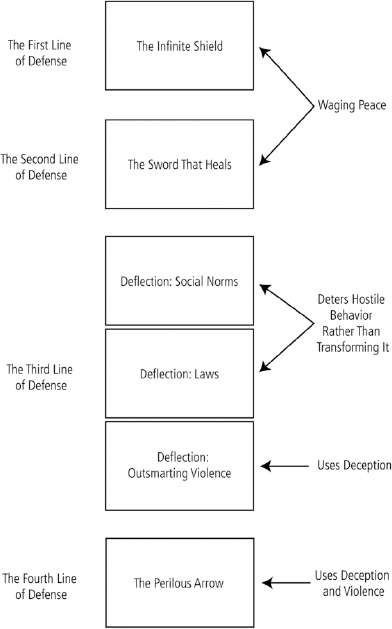

There is also a practical reason for balancing truth with tact, because the more disrespectful and condescending you are when speaking the truth the more difficult it is for people to hear it. A highly trained peace warrior is not just a truth teller, but a skilled truth teller. To illustrate the differences between deflection and the truth telling of waging peace, the following diagram depicts the four lines of defense:

Figure 5.2 The Four Lines of Defense

To protect us from violence and injustice, the infinite shield and the sword that heals are the first two lines of defense. They are waging peace. The third line of defense is deflection. It is not waging peace, because the first two forms of deflection (social norms and laws) deter hostile behavior rather than transform people’s ignorance and hatred into understanding and compassion, and the third form of deflection (outsmarting violence) permits deception. The fourth line of defense, which I call the perilous arrow, permits not only deception but also violence. The fourth line of defense is the furthest thing from waging peace, because the perilous arrow is violence itself.