It was a spectacle for the ages. The normally buttoned-down business world, propelled by the galloping pace of globalization and deregulation, delivered enough drama to light up every theater on Broadway.

Even with Howard J. Ruff’s doomsaying book, “How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years,” still on the best-seller lists, the Dow Jones reached dizzying heights, breaking records every week, or so it seemed, and radiating the excitement of a casino. It was the decade of the hostile takeover. Wall Street buccaneers, audacious and swaggering, engineered a stunning series of acquisitions that rocked the financial world. It was high-stakes drama as mammoth corporations swallowed each other one by one, making media stars not only of the dealmakers but also of the journalists who covered them.

Risk arbitrager Ivan Boesky in his office in the early 1980s.

It was a gambler’s dream come true until, in 1987, the market plunged earthward at a terrifying speed.

The decade cried out for a Balzac to capture the drama, and it found one in Tom Wolfe. His satirical novel “The Bonfire of the Vanities” captured the ethos of the decade, the vaunting ambition and unbridled acquisitiveness epitomized by the Wall Street traders he called “masters of the universe.” On film, the director Oliver Stone dramatized the financial free-for-all through the character of Gordon Gekko, a ruthless arbitrageur whose motto, “greed is good,” became one of the catchphrases of the decade.

A trader on the New York Stock Exchange watches as the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunges in October of 1987.

The once-staid world of the Fortune 500 reached a frenzied boil. A Supreme Court decision forced AT&T to break up the Bell System, a telephone monopoly that Americans had thought of as immutable. Deregulation opened the way for new airlines like People Express and crippled venerable carriers like Eastern, TWA and Pan Am, which were in their death throes by the end of the decade.

It was the heyday of the corporate raider. Risk-takers like Carl Icahn, T. Boone Pickens and Saul Steinberg made an art of the hostile takeover, using debt as a tool to acquire big companies for relatively little upfront cash in a maneuver that soon became known to one and all: the leveraged buyout. At the investment banking firm of Drexel Burnham Lambert, whiz kid Michael Milken made his name by financing takeovers with the speculative, high-yield instruments known by the undignified name of junk bonds.

Michael Douglas posing as Gordon Gekko from the movie “Wall Street.”

As the federal government relaxed its antitrust regulations, merger and acquisition mania took hold. Capital Cities Communications bought ABC, General Electric bought RCA and Philip Morris bought Kraft Foods. Time Inc. merged with Warner Communications, Bristol-Myers with Squibb, Bridgestone with Firestone. And in the largest leveraged buyout ever seen, the private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts paid $25 billion for RJR Nabisco, itself a product of the 1985 merger of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco and Nabisco Brands.

The whole world seemed intoxicated by financial wheeling and dealing. In a newly deregulated Britain, London emerged as a linchpin for global finance. Even China, awakening from the spell of Mao and the Communist Revolution, put a modest chip on the table, establishing its own stock exchange.

London’s Stock Exchange in the 1980s.

It all seemed too good to be true, and it was. The stock market boomed. Real estate prices shot sky-high in New York, Paris and London. Art fetched record prices at the auction houses. Great fortunes were made. It all seemed too good to be true, and it was. The government prosecutors began looking at insider trading, unscrupulous deals and fraud.

In a foreshadowing of things to come, the arbitrageur Ivan Boesky, who had amassed a huge fortune by betting on corporate takeover, was convicted of insider trading and sentenced to prison in 1986.

U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani (right) and SEC Sleuth Gary Lynch, special investigator, announcing one of the many insider trading indictments in the late 1980s.

As the decade wound to a close, Michael Milken faced the music too. The junk-bond king, widely assumed to be the model for Gordon Gekko, was indicted on 98 counts of racketeering and securities fraud in 1989. After pleading guilty to lesser charges, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison and barred for life from working in the securities industry.

It was a symbolic moment, and seen as such. The masters of the universe, at decade’s end, were in retreat. It seemed only fitting that a best-seller by James R. Stewart describing their exploits should be titled “Den of Thieves.”

Japan Tops U.S. in 1980 Car Output

TOKYO, Dec. 23–Japan has become the world’s largest vehicle producer, the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association said today.

Through the first 11 months of the year, Japanese vehicle production, including cars, trucks and buses, reached a record 10.1 million units, association officials said. The figure represents a 15.1 percent increase over 1979.

A view of Japanese Honda cars being offloaded from a freighter.

During the same period, the association said, United States production fell to about 7.4 million units, down from 10.9 million in 1979.

From January to November 1980, Japanese auto makers produced 6.4 million cars, up 14.4 percent over a year earlier; 3.6 million trucks, up 15.9 percent, and 82,620 buses, up 46.5 percent.

APRIL 26, 1981

HOW TO START AN AIRLINE:

People Express Poised to Fly

“There it goes now,” said Gerald L. Gitner. The Boeing 737 roared on takeoff past the second-floor corner office window at Newark Airport’s North Terminal. Mr. Gitner and Donald C. Burr watched like proud fathers. The gleaming jet, the first in their proposed fleet, was undergoing tests last week by a team from the Federal Aviation Agency. Mr. Burr, 39, and Mr. Gitner, 36, plan to give birth to an airline this Thursday.

Customers boarding People Express plane for their first $69 flight from Newark to Dallas/Ft. Worth.

Its name is People Express Airlines, and its goal is to make money by flying people cheaply from Newark to such places as Buffalo, Norfolk and Columbus and back. Mr. Burr, who is chairman and chief executive, and Mr. Gitner, president and chief operating officer, say they can fly people for less than the price of driving or taking the bus. They will charge $23 to Buffalo and Norfolk and $35 to Columbus on weekends and evenings.

That is a lot less than the current fares charged by other airlines of $99 to Buffalo, $82 to Norfolk and $146 to Columbus. But the airlines that fly these routes are slashing ticket prices to meet the People Express competition. On the Buffalo route, for example, US Air will meet the People Express fare and Piedmont will do the same on the Norfolk run.

Thus it appears that People Express is in for a ferocious fight as it tries to get a toe-hold in the busy Northeast market. Parts of the airline business these days are beginning to resemble the pioneering era when barnstormers-turned-businessmen scrambled to found the mail lines that became the nation’s major air carriers. Today, airlines like People Express are springing up as a result of the Government’s 1978 deregulation of fares and route structures, and the competition is fierce. They are trying to copy the earlier fare-cutting successes of PSA in California and Southwest Airlines in Texas in the days when those airlines operated within state lines to stay out of Washington’s regulatory clutches.

“The Deregulation Act looked like a whole new thing,” Mr. Burr said. “Now, even more, it’s clear that we’re only on the leading edges of a new era not dissimilar in a sense from the old days when airlines got under way.”

Some of these aggressive new airlines are Midway in Chicago and Air Florida. In this region, Eastern Airlines is already locked in combat for its shuttle business with New York Air, a subsidiary of the Texas Air Corporation, which also operates Texas International Airlines. New York Air has plans to expand cut-rate service to other Northeast cities.

JANUARY 9, 1982

U.S. SETTLES PHONE SUIT, A.T.& T. TO SPLIT UP, TRANSFORMING INDUSTRY

WASHINGTON, Jan. 8–The American Telephone and Telegraph Company settled the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit today by agreeing to give up the 22 Bell System companies that provide most of the nation’s local telephone service.

On a landmark antitrust day, the Justice Department also dropped its marathon case against the International Business Machines Corporation that had sought to break up the company that has dominated the computer industry. The Justice Department said the suit was “without merit and should be dismissed.”

The A.T.& T. agreement, if finally approved by a federal court, would be the largest and most significant antitrust settlement in decades. It is likely to be compared with the 1911 settlement that divided the Rockefeller family’s Standard Oil Company into 33 subsidiaries, some of them huge oil companies in their own right.

The heart of the agreement requires A.T.& T. to give up all its wholly owned local telephone subsidiaries, which are worth $80 billion, or two-thirds of the company’s total assets. That would radically alter a company that has accounted for more than 80 percent of the nation’s telephone service, changing the course of the industry.

But A.T.& T. would be free to enter such previously prohibited fields as data processing, communications between computers and the sale of telephone and computer terminal equipment, all rapidly growing and a profitable aspect of the telecommunications industry. And it would retain its long-distance service.

A critical aspect of the proposed settlement is that it would sever a key source of the giant company’s economic and political power, namely the phone companies that blanket nearly every major metropolitan area of the nation and provide a protected market for the parent company’s equipment production and facilitated the long distance service. A number of analysts speculated that A.T.& T. agreed to the huge divestiture because the company feared that Judge Greene, who was expected to rule on the case early this summer, would find the phone company guilty of antitrust law violations and perhaps force it to give up other subsidiaries as well.

The phone companies that would be spun off include the following: Bell Telephone of Nevada, Illinois Bell Telephone, Indiana Bell Telephone, Michigan Bell Telephone, New England Bell Telephone and Telegraph, New Jersey Bell Telephone and New York Telephone.

Many of the actual and potential competitors of A.T.& T. are expected to have much to say. For instance, Thomas E. Wheeler, president of the National Cable Television Association, which has always dreaded A.T.&T.’s possible entry into that business, criticized the “closed-door agreement” and said that only Congress should be allowed to restructure the industry.

EUPHORIC DAY FOR WALL STREET

From the president of the New York Stock Exchange to a trainee on the floor of the American Exchange, Wall Street workers concluded yesterday that, despite record-breaking volume, the industry breezed through what might soon become just another day at the corner of Broad and Wall.

“We can handle 250 million to 300 million shares a day,” asserted John J. Phelan Jr., president of the New York exchange, “whether it’s all big financial institutions or all individual retail orders or any mix of both.”

Asked how he could be so confident—particularly in view of yesterday’s 147-million-share volume—Mr. Phelan replied: “Because we’ve built models and tested them up to about 300 million shares and 250,000 transactions. That’s twice the volume today and five times the number of transactions.”

On the Big Board trading floor, where the sound level intensified dramatically in the final hour of activity, traders waved at photographers, reporters and others present to record the historic event. Some blew police whistles. Others tossed sheets of paper into the air. At the 4 P.M. close of trading, the traditional shout normally associated with such big events rang out across the huge arena, partly to please the news media, and the exchange’s fire bell brought the day to a dramatic close.

Ronald Pompei, a 23-year-old Amex floor trainee from Elmsford, N.Y., described the heavy trading there as “like being in the middle of a subway in rush hour.”

On the Big Board trading floor, Robert Guarino, a floor member of Wedbush, Noble, Cooke, said: “I’m so busy I can’t even take phone calls. This morning we had a lot of buying. This afternoon we had a lot of selling because of profit taking.”

The public also seemed to be caught up in the general euphoria, characterized by Michael Sylvester, a phone clerk for Boettcher & Company, as “the electricity and excitement in the air.” At Grand Central Station, the lines in front of Merrill Lynch’s stock price video screens were longer than those in front of the commuter information boards.

But yesterday, the “regulars” were joined by executives in pin stripes—often with briefcase in one hand, ice cream cone in the other.

Those at the Merrill Lynch bubble gave President Reagan and his economic program little credit for the market’s rally. Many attributed it to the approaching November elections, and there was a widespread feeling that the rally would be short-lived.

“To me as a layman, there is no sound underlying economic reason for this volume and rise in good issue stocks,” said John L. Tabakman, 70, a retired train dispatcher. “It’s the politicians, the elections,” he continued. The rally would not help the Republicans in November, he said in response to a question, because “too many people are out of work.”

Overview of the New York Stock Exchange in the early 1980’s.

JANUARY 15, 1984

RAY A. KROC DIES AT 81; BUILT MCDONALD’S CHAIN

Ray A. Kroc, the builder of the McDonald’s hamburger empire, who helped change American business and eating habits by deftly orchestrating the purveying of billions of small beef patties, died yesterday in San Diego. He was 81 years old and lived in La Jolla, Calif.

Mr. Kroc, who also owned the San Diego Padres baseball team, died of a heart ailment at Scripps Memorial Hopsital in San Diego, a McDonald’s spokesman said. At his death he was senior chairman of McDonald’s.

Mr. Kroc, a former piano player and salesman of paper cups and milkshake machines, built up a family fortune worth $500 million or more through his tireless, inspired tinkering with the management of the McDonald’s drive-ins and restaurants, which specialize in hamburgers and other fast-food items.

He was a pioneer in automating and standardizing operations in the fiercely competitive, multibillion-dollar fast-food industry. He concentrated on swiftly growing suburban areas, where family visits to the local McDonald’s became something like tribal rituals.

He started his first McDonald’s in Chicago in 1955 and the chain now has 7,500 outlets in the United States and 31 other countries and territories. The total system-wide sales of its restaurants were more than $8 billion in 1983. Three-quarters of its outlets are run by franchise-holders.

What made Mr. Kroc so successful was the variety of virtuoso refinements he brought to fast-food retailing. He carefully chose the recipients of his McDonald’s franchises, seeking managers who were skilled at personal relations; he relentlessly stressed quality, banning from his hamburgers such filler materials as soybeans.

Mr. Kroc also made extensive, innovative use of part-time teenage help; he struggled to keep operating costs down to make McDonald’s perennially low prices possible, and he applied complex team techniques to food preparation that were reminiscent of professional football.

Ray Albert Kroc went to public schools in Oak Park, but did not graduate from high school. In World War I, like his fellow Oak Parker, Ernest Hemingway, he served as an amublance driver. Then, after holding various jobs, he spent 17 years with the Lily Tulip Cup Company, becoming sales manager for the Middle West.

By 1941 he became the exclusive sales agent for a machine that could prepare five milkshakes at a time.

Then, in 1954, Mr. Kroc heard about Richard and Maurice McDonald, the owners of a fast-food emporium in San Bernadino, Calif., that was using several of his mixers. As a milkshake specialist, Mr. Kroc later explained, “I had to see what kind of an operation was making 40 at one time.”

Mr. Kroc talked to the McDonald brothers about opening franchise outlets patterned on their restaurant, which sold hamburgers for 15 cents, french fries for 10 cents and milkshakes for 20 cents.

HELPED CHANGE AMERICAN EATING HABITS

Eventually, the McDonalds and Mr. Kroc worked out a deal whereby he was to give them a small percentage of the gross of his operation. In due course the first of Mr. Kroc’s restaurants was opened in Des Plaines, another Chicago suburb, long famous as the site of an annual Methodist encampment.

Business proved excellent, and Mr. Kroc soon set about opening other restaurants. The second and third, both in California, opened later in 1955; in five years there were 228, and in 1961 he bought out the McDonald brothers.

Under Mr. Kroc’s persistent goading, McDonald’s insisted that franchise owners run their own outlets. It also poured hundreds of millions of dollars into advertising—to the point where the head of another fast-food company said in 1978 that consumers were “so preconditioned by McDonald’s advertising blanket that the hamburger would taste good even if they left the meat out.”

Mr. Kroc suffered a stroke in December 1979 and soon afterward entered an alcoholism treatment center in Orange, Calif., because, he said at the time, “I am required to take medication which is incompatible with the use of alcohol.”

On Language; Beware the Junk-Bond Bust-Up Takeover

“The combination of bust-up takeover threats with greenmail has become a national scandal,” writes Martin Lipton, a lawyer, in The New York Law Journal. He adds, ominously, “The junk-bond bust-up takeover is replacing the two-tier bootstrap bust-up takeover.”

“National scandal” is the only phrase I recognize in that burst of tycoonspeak. “The new vocabulary of our business,” the investment banker Felix G. Rohatyn has written, reflects a go-go atmosphere in which “two-tier tender offers, Pac-Man and poison-pill defenses, crown-jewel options, greenmail, golden parachutes, self-tenders all have become part of our everyday business.”

Let us master that lexicon by considering the individual words and phrases. (This will be a lexical bust-up takeover.) When Brian Fernandez of Normura Securities is quoted in Newsweek as saying, “I’m sure I.T.T. has a mine field of poison pills and shark repellent to keep people away,” what does he mean?

Shark repellent is the action taken by a company’s board of directors to shoo away raiders—the “sharks” circling the company and hoping to chew it up. (The much-derogated sharks can be investors wanting virtuously to throw out inefficient management that has been living off the stockholders’ backs, but let’s look at takeovers from the point of view of the fearful company.)

“One way to repel sharks is to stagger the board of directors,” reports Fred R. Bleakley of The New York Times. “Instead of having the terms expire for all the board members at the same time, making a takeover easier, the staggering might mean that only one member’s term expires at any given time,” which might try a shark’s patience. Another repellent is a fair-price amendment to the company’s bylaws, preventing the shark from offering different prices on bids to different stockholders for their shares. Yet another is the crown-jewel option, selling off the most profitable segment of the company; this comes from the figurative use of “the jewel in the crown,” now the title of a television series having nothing to do with the world of big business.

My favorite repellent is the poison pill, taken from the world of espionage, in which the agent is supposed to bite a pellet of cyanide rather than permit torture after capture (the Central Intelligence Agency finds it hard to get agents to do that anymore). To make a stock less attractive to sharks, a new class of stock may be issued: this is “a preferred stock or warrant,” Arthur Liman, a lawyer, informs me, “that becomes valuable only if another company acquires control. Because it becomes valuable to the target, it becomes costly to the buyer: when the buyer takes the bite, to follow the metaphor, he has to swallow the poison pill.”

A junk bond is a high-yield, high-risk security specially designed to finance a takeover; this is supposed to enable the issuer of the bond to get enough bank financing to offer stockholders cash for all the stock in the company. “Following the takeover,” writes Mr. Lipton, “the target is busted up to retire part of the takeover financing. Plants are closed, assets are sold, employees are thrown out of work and pension plans are terminated.” That’s what comes of a junk-bond bust-up takeover.

In extremis, a corporate survivor can try greenmail. First the shark swims around the company, showing its wicked fin and making menacing splashes; the shark keeps buying stock, but not enough to take over. Then the shark offers the frightened directors on the life raft a deal: use company assets to buy in the shark-held stock at a premium, higher than the market price. Big profit for shark, safe jobs for management, and only the other company stockholders get hurt. This is the sort of thing the labor racketeer Louis (Lepke) Buchalter did for garment-center operators in the good old days: the shark sells protection from shark bites. The essence of green-mail is the bonus paid over the market price: “We certainly don’t identify it as greenmail,” said T. Boone Pickens Jr. of his withdrawn bid to take over Phillips Petroleum, “because we negotiated substantially the same deal for the stockholders as we got for ourselves.”

“Greenmail is patterned on blackmail, with the green representing greenbacks,” reports Sol Steinmetz, a lexicographer, of Barnhart Books. “It may have been inspired by the earlier graymail.” That is a threat by a defense attorney to force the government to drop an espionage case by demanding the exposure of secrets.

I am not going into two-tier tender offers or Pac-Man defenses because it is not my intent to steal students from the Harvard Graduate School of Business, but the golden parachute deserves etymological examination. This agreement to pay an executive his salary and benefits, even if the company is taken over by somebody who wants to heave him into shark-infested waters, is based on golden handcuffs, coined in 1976 to mean “incentives offered executives to keep them from moving to other jobs.” In turn, this was based on the British golden handshake, a 1960 term for a whopping sum given as severance pay.

You are now prepared for a raid on a medium-size lemonade stand. If in trouble, get yourself a White Knight, which is either a friendly bidder or a washday miracle.

MARCH 19, 1985

ABC IS BEING SOLD FOR $3.5 BILLION

The American Broadcasting Companies agreed yesterday to be sold to Capital Cities Communications Inc. for more than $3.5 billion.

The surprise deal represents the first time that ownership of any of the nation’s three major networks has changed hands. It also represents the biggest acquisition outside the oil industry in corporate history.

ABC, with 214 affiliated stations, has been a major cultural force in the nation, broadcasting such popular programs as “Dynasty” and “Hotel” and capturing a wide audience with its Olympics programming last summer. Capital Cities, a little-known but ambitious stalker of broadcast and publishing properties, owns television and cable TV systems, the Fairchild Publications business newspaper group and several daily newspapers.

Thomas S. Murphy, the 59-year-old cost-conscious chairman and chief executive of Capital Cities, and Leonard Goldenson, the strong-willed 79-year-old chairman and chief executive of ABC, said they had been talking on and off since early December, though the deal was essentially patched together over the last two weekends.

“We just thought it was a natural fit between the two companies,” Mr. Murphy said in an interview yesterday, “and we thought we’d have an opportunity to handle the new possibilities coming up in the electronics fields better together.”

But the agreement, approved by both companies’ boards of directors, means the twilight of the long reign of Mr. Golden-son, the chief builder who put ABC together. Once the merger is completed, he will be reduced to chairman of the consolidated company’s executive committee.

“That is my wish,” Mr. Goldenson said. “I feel that the company I built from scratch is in good hands and that it will be carried on, and that’s important to me.”

Clockwise from the top left: Frederick S. Pierce, President ABC, Inc.; Daniel B. Burke, President of Capital Cities/ABC, Inc; Leonard H. Goldenson, Chairman, ABC, Inc.; and Thomas S. Murphy, Chief Executive Officer, Capital Cities/ABC, Inc.

To get ABC, a company four times its size, Capital Cities is offering to pay ABC’s stockholders a hefty $118 a share in cash plus warrants to buy Capital Cities stock at a set price. ABC’s stock rose $31.375 yesterday, closing at $105.375. As a result of this sizable outlay, however, Capital Cities will gain entry to the glamorous and powerful world of network broadcasting.

“There are certainly cross-ownership questions,” said James McKinney, chief of the F.C.C.’s mass media bureau, the division with responsibility for broadcasting oversight. “I would guess they will come in with a plan fairly shortly.”

Elsewhere, Ted Turner, the owner of Turner Broadcasting System Inc., is reported to be considering a bid for the CBS network. Meanwhile, a conservative group, with the backing of Senator Jesse Helms, Republican of North Carolina, was put together to raise cash to buy CBS stock as a way of challenging what the group calls the liberal bias of CBS News.

CBS said it had no comment on the ABC-Capital Cities agreement. NBC said only that it wished both companies well.

AUGUST 22, 1985

MICROSOFT AND I.B.M. JOIN FORCES

SAN FRANCISCO, Aug. 21–The International Business Machines Corporation has agreed with the Microsoft Corporation, a key software supplier, to develop fundamental software for personal computers, the companies said today.

Microsoft owner and founder Bill Gates poses in front of hundreds of boxed Microsoft products in 1986.

But Microsoft will be able to sell the jointly developed operating systems to other computer manufacturers, which should allay industry fears that I.B.M. would one day migrate to its own, proprietary operating system. That could have locked others in the industry out of the market and made it impossible for existing software to run on future I.B.M. computers.

The agreement states that I.B.M. and Microsoft will work together on personal computer operating systems, the software that directs the computer in performance of basic operations such as retrieving information from data storage disks. Microsoft already supplies the MS-DOS operating system used in I.B.M. computers and other computers compatible with the I.B.M. machines.

As to the industry fears that I.B.M. will lock out its competitors, “If anything will eliminate it, this will eliminate it,” said William H. Gates, the chairman and chief executive of Microsoft. “It’s very clear that this is a reaffirmation of the importance of DOS.”

“I think it’s good for us from an outside perception viewpoint,” said Ben Rosen, the chairman of the Compaq Computer Corporation, the leading supplier of I.B.M.-compatible personal computers. He said the agreement would help assure customers of what Compaq has always believed—that I.B.M. will not desert the open MS-DOS operating system.

The agreement calls for the two companies to cooperate on the development of operating systems and other systems software products. While future versions of MS-DOS are included, the companies did not specify what else might be included. But it is likely the agreement calls for them to work on computer programming language, networks for connecting computers together and “windowing environments” that allow several tasks to appear on the screen at the same time, each in its own little “window.” Microsoft is already working on future versions of its operating systems, known as versions 4.0 and 5.0, that will take advantage of more powerful computers now being built.

The new versions are expected to allow several tasks to be performed at once on the computer, whereas the existing MS-DOS can only handle one application at a time. The new versions will also be able to handle more computer memory. The current versions can only handle up to 640,000 characters of memory, whereas it is not uncommon now for computers to have one million characters of storage or more.

Microsoft, based in Bellevue, Wash., was catapulted to the lead in the software business when I.B.M. chose its operating system five years ago. Since then it has grown to $140 million in revenues and diversified. MS-DOS sales now represent about 20 percent of its revenues. Its sales to I.B.M. account for less than 10 percent, Mr. Gates said.

SEPTEMBER 19, 1985

APPLE COMPUTER ENTREPRENEUR’S RISE AND FALL

SAN FRANCISCO, Sept. 18–In his years of guiding Apple Computer Inc., Steven P. Jobs had become the epitome of the American entrepreneur, a symbol of the wealth and power that can arise almost overnight in California’s Silicon Valley.

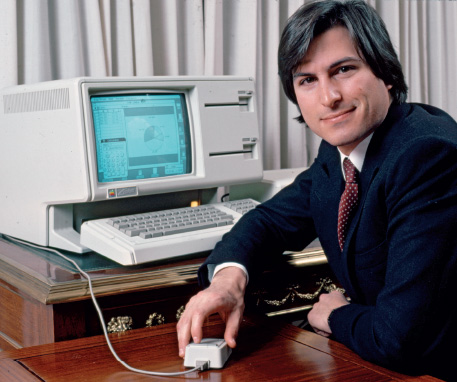

Steve Jobs with the Lisa computer in 1983.

Even President Reagan, in a recent address, urged the nation’s youth to “follow in the footsteps of those two college students who launched one of America’s great computer firms from the garage behind their house.”

The tale of Mr. Jobs’s visionary leadership at Apple came to a bitter end on Tuesday when he resigned as the company’s chairman after disclosure of his plans to start a new company.

Mr. Jobs would not comment in detail today on the developments that led to his fall from grace at Apple.

But according to associates, the same vision, drive and ego that helped Mr. Jobs make Apple into a leading personal computer company also prevented him from heeding the advice of others to the point that Apple, which at one time seemed unstoppable, is in worse financial shape than it has ever been.

“He only trusted himself to be the high leader,” said Stephen Wozniak, who founded Apple with Mr. Jobs in 1976 and has since seen his relations sour with his former partner.

Mr. Jobs, at 30 years old a millionaire many times over, lost operating authority of the company in the spring, but remained its largest shareholder and chairman of the board. His impatience with this reduced role led him, in the best Silicon Valley spirit, to do what entrepreneurs do best: start a new company. It was this that caused the final rift with Apple’s current management.

Apple is not considered to be in danger of failing, although some computer analysts say the company, in a weakened condition, may be a takeover target. But the job of guiding Apple now belongs more than ever to John Sculley, the president and chief executive officer recruited from Pepsico two years ago by Mr. Jobs personally.

Mr. Jobs’s resignation culminates a tumultuous power struggle with Mr. Sculley that began earlier this year as Apple’s fortunes started to decline, a power struggle that Mr. Sculley has compared to a real-life version of “Dynasty,” the television program.

Mr. Jobs’s resignation from that position was precipitated by a dispute over plans to start his own company to make unspecified computer products for the higher education market. Apple officials say they feel betrayed that Mr. Jobs might compete with Apple, since the higher education market is one of Apple’s strongholds. In addition, Mr. Jobs plans to hire five Apple employees.

Like many legends, the story of Apple is somewhat exaggerated, even by President Reagan. Mr. Jobs and Mr. Wozniak were not college students, but were college dropouts who hung around together in the garage at the home of Mr. Jobs’s parents, tinkering with electronics. Some of their first devices were boxes that allowed them to make longdistance calls without paying.

It was Mr. Wozniak who actually did the engineering work to design the Apple II computer, which became a best-seller. But Mr. Jobs was the one who wanted to start a company and blustered his way into getting Apple a supply of parts and a top-notch public relations firm before the company was hardly out of the garage.

He became the company’s visionary, conceptualizing products like the Macintosh. “He seemed to be able to see slightly beyond the horizon when other people couldn’t see beyond the end of their nose,” said Michael Moritz, senior editor of the Technologic Computer Letter, an industry newsletter, and author of “The Little Kingdom,” a history of Apple.

Mr. Jobs could inspire and charm, getting people to follow him down any path. “He was always so persuasive the way he would say things,” said Mr. Wozniak, who, despite his falling out with Mr. Jobs, called him “the finest technical leader Apple has ever had.”

But Mr. Jobs could also be arrogant and alienate people who worked with him and take revenge on people who crossed him. Former Apple employees say they were afraid to disagree with Mr. Jobs.

Apple, while having a solid management, still might miss Mr. Jobs. The company is weak in top engineering talent to guide product development. Moreover, more traditional managers like Mr. Sculley have often proved no more adept at running technology companies than the original entrepreneurs. Some analysts and former employees are worried that Apple is losing its spark and becoming stodgy, a process some refer to as “Scullification.”

“The great sadness and the great tragedy” of the departure of Mr. Jobs from Apple, Mr. Moritz said, “is that both the company and he personally would be better off if they were still together.”

DECEMBER 12, 1985

G.E. WILL PURCHASE RCA IN A CASH DEAL WORTH $6.3 BILLION

The General Electric Company agreed yesterday to acquire the RCA Corporation, owner of the NBC television network and a leading defense and consumer electronics company, in a cash deal worth nearly $6.3 billion.

The General Electric (GE) building, formally known as the RCA building, in Rockefeller Center, New York City.

The announcement was the second this year of a network takeover. The acquisition of the American Broadcasting Companies for $3.5 billion by Capital Cities Communications was announced in March.

An excellent strategic opportunity

Word of the merger agreement between G.E., a broadly based electronics firm founded by Thomas Alva Edison, and RCA, which G.E. helped found in 1919, was apparently less of a surprise to the financial community. Before the news yesterday, the price of RCA’s stock jumped nearly 20 percent on extraordinarily heavy volume of 5.1 million shares.

The agreement reunites two companies that helped each other grow from the end of World War I, but became fierce competitors in pursuit of communications technology. Their combined revenues would make them together the nation’s seventh-largest industrial corporation, sandwiched between the International Business Machines Corporation and the du Pont Company.

While details of the merger were sketchy, G.E. said it would pay $66.50 a share in cash for RCA’s 94.4 million shares. The total price of $6.28 billion matches the transaction for the largest non-oil company acquisition. Earlier this year, Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts & Company agreed to buy the Beatrice Companies, a Chicago-based consumer products company, for $6.2 billion.

In a statement last night, the companies said the merger is “an excellent strategic opportunity for both companies that will help America’s competitiveness in world markets.”

The transaction may have been helped along by the fact that executives from both companies know each other well.

G.E. chairman chairman, John F. Welch Jr, who is 50 years old and took over as head of the company in 1981, is expected to remain in charge of the combined company. Also likely to stay on is Robert R. Frederick, president and chief executive of RCA, who was formerly a G.E. executive.

SALE OF BINGHAM PAPERS NEARS

LOUISVILLE, Ky., May 15–In a rare break with tradition, the elegant breakfast usually given by the Bingham family on the morning of the Kentucky Derby did not take place this year.

At The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times, the newspapers that are the heart of the Bingham family’s communications empire, mordant staff members have set up betting pools on who will acquire the newspapers, and at what price.

In this atmosphere of anxiety, sadness and circus, on Friday the warring members of the Bingham clan will gather to try to select a new owner for The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times, thus ending the nearly 70-year reign of the Binghams, whose Kentucky communications empire made them one of the state’s most powerful families. The deliberations could go into next week.

While those submitting bids for the newspapers have not been identified, they are thought to include the Gannett Company, the Washington Post Company and the Tribune Company of Chicago.

“It’s the passing of an era that we’ll never see again,” said Harvey I. Sloane, county judge executive of Jefferson County, which includes Louisville.

The decision to sell all the family holdings was announced on Jan. 9 by Barry Bingham Sr., the 80-year-old patriarch and chairman of the family companies. That decision, which came after years of bitter feuding over the family business by his three children, was immediately denounced as a “betrayal” by Barry Bingham Jr., his only surviving son and the operational head of the family enterprises.

While the Louisville newspapers are considered editorial plums, analysts say they come encumbered with economic drawbacks such as a flat Louisville economy and expensive statewide circulation that has been maintained more for prestige and tradition than for profit. A new printing plant that some analysts say is needed could cost $75 million, and the new owner will likely merge the newspapers into one, which could mean the elimination of a hundred editorial jobs or more.

NOVEMBER 15, 1986

BIG TRADER TO PAY U.S. $100 MILLION FOR INSIDER ABUSES

WASHINGTON, Nov. 14–Ivan F. Boesky, one of the biggest and best-known speculators on Wall Street, has agreed to pay a $100 million penalty for illegal insider trading, the Government announced today.

The sum was by far the largest ever assessed against someone who has reaped “ill-gotten gains,” said John S. R. Shad, the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, which announced the penalty. Half of the sum represents illegal profits, the other half a civil penalty.

In addition to the financial penalty, Mr. Boesky, chief executive of Ivan F. Boesky & Company, an investment firm, after an 18-month phase-out period, will be barred for life from the American securities industry.

The investigation arose out of a case against Dennis B. Levine, the merger specialist at the center of a trading scandal, who has cooperated with the Government, as Mr. Boesky is doing now. According to the S.E.C., Mr. Boesky had agreed to pay Mr. Levine 5 percent of the profits made on some of his biggest transactions.

The Government said Mr. Levine, a former managing director of the Wall Street firm of Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., gave Mr. Boesky inside information concerning takeover and other activity surrounding Nabisco Brands, American Natural Resources, Union Carbide, General Foods and other big companies. Insider trading takes place when securities are bought or sold on the basis of information that is not yet available to the public.

Mr. Boesky is a specialist in the high-tension, high-stakes world of risk arbitrage, where stocks are bought in anticipation of a takeover, a merger or change in corporate ownership. The son of a Russian immigrant delicatessen owner in Detroit, Ivan Boesky was known as a loner among other risk arbitragers, a man called “Ivan the Terrible” for his apparent success in trading stocks.

Ivan Boesky leaves the New York District U.S. Courthouse after pleading guilty on April 23, 1987.

Newspaper reports put his personal wealth in excess of $250 million. He was said to have a 300-button telephone console in his office, and three phones in his chauffeur-driven car. As a trader, he realized profits of legendary proportions in such takeovers as Chevron’s purchase of Gulf Oil and Texaco’s purchase of Getty Oil. Those were two of the biggest such transactions ever, and both predated the period covered by the S.E.C. complaint.

“Risk arbitrage is not illegal,” Mr. Shad, the S.E.C. chairman, told a news conference. “But it is illegal to trade on material, nonpublic information.”

Mr. Shad added: “This will have a significant impact on many of the people engaged in risk arbitrage, in making sure they don’t step over the line.”

BOESKY SENTENCED TO 3 YEARS IN JAIL IN INSIDER SCANDAL

Ivan F. Boesky, once among the financial world’s most powerful speculators and now a symbol of Wall Street’s excesses, was sentenced yesterday to three years in prison for conspiring to file false stock trading records.

According to records kept by the United States Attorney’s office in Manhattan, the three-year term is the third longest to have been imposed in a case related to insider trading. Mr. Boesky had faced a maximum penalty of five years in jail and a $250,000 fine.

Comments by the judge, the United States Attorney and Mr. Boesky’s lawyer underscored both the enormity of Mr. Boesky’s crimes, the unimagined scope of the corruption on Wall Street that he exposed to the Government and the extent to which his cooperation led to a broadening of the insider trading scandal.

Judge Lasker said he believed that Mr. Boesky had reformed, but emphasized that a prison term was necessary to try and stanch what he characterized as widespread disregard for the law in business and government.

“Ivan Boesky’s offense cannot go unpunished,” Judge Lasker said. “Its scope was too great, its influence too profound, its seriousness too substantial merely to forgive and forget.”

“Recent history has shown that the kind of erosion of morals and standards and obedience to the law involved in a case such as this is unhappily widespread in both business and government,” he added. “The time has come when it is totally unacceptable for courts to act as if prison is unthinkable for white-collar defendants but a matter of routine in other cases. Breaking the law is breaking the law.”

During the hearing Mr. Boesky spoke in an almost inaudible whisper, telling the judge that he had expressed his remorse at a pre-sentencing hearing on Dec. 3. “I felt it deeply then and I feel it even more deeply now,” he told the court yesterday.

U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani announces Ivan Boesky’s jail sentence for inside trading at Federal Courthouse in New York City.

APRIL 27, 1987

A Debate in China Over Stock Trading

Before the Communist victory in 1949 exorcised almost all traces of capitalism from China, this city boasted of having the biggest stock market in Asia. Now, as the nation tentatively rediscovers the need for capital markets, Shanghai has a new stock exchange—one that lists four stocks and two bonds.

When one of the bond issues went on sale in late January, more than 3,000 would-be customers, some of whom had lined up the day before, nearly broke down the iron gate in front of the bank.

But whether the public will be allowed to satisfy its craving to invest in bonds and stocks—which in China sometimes look more like debt instruments—is still open to question. A debate continues in the highest levels of the Communist Party over the suitability of trading securities in a socialist economy.

Shenyang became the first city in China to reopen a stock exchange

Just a few months ago the trend seemed to favor shareholding. Last August the northeastern city of Shenyang became the first city in China to reopen a stock exchange, and since then exchanges have opened in Shanghai, Beijing, Wuhan and Tianjin. When the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, John J. Phelan Jr., visited China last fall, he was granted a long audience with the country’s supreme leader, Deng Xiaoping.

In an article in the official Beijing Review in December, a Beijing University economist predicted a vast expansion of shareholding. The economist, Li Yining, proposed what amounted to the privatization of China: turning state-owned companies into stock-issuing concerns owned by their shareholders.

Shares of stock traded on the Shanghai stock exchange.

Foreigners so far are not permitted to participate in the securities market—although prominent visitors are allowed to buy a single share as a souvenir. For that reason, and because any securities profits would be in local currency and could not be converted, international securities firms have not paid much attention to the stock markets in China.

For companies, the great advantage of issuing stocks or bonds is being able to grow without the uncertainties of arranging bank loans. According to official figures, more than 6,000 companies throughout China have issued shares worth $1.6 billion, but that equals only 1 percent of the loans last year in the banking system.

DECEMBER 13, 1985

G.E.’S DEMANDING CHAIRMAN

STAMFORD, Conn., Dec. 12–In four years as the chairman of the General Electric Company, John F. Welch Jr. has become known simultaneously as one of the nation’s toughest executives, as an intellectually astute manager and as a man more inclined to demand action immediately than wait for a second opinion.

Mr. Welch has made his mark on G.E., where sharp cost cutting, plant modernization and a host of management changes have made him something of a guru in business circles.

Still, one of the questions that loomed large in the wake of Wednesday’s merger announcement by G.E. and the RCA Corporation was whether he has the diplomatic skills to mesh the assets and personalities of two major companies.

“Diplomacy?” remarked the 50-year-old Mr. Welch today. “I don’t think anybody could recall a more diplomatic merger.” He added: “This was not a takeover. This is a merger that makes great strategic sense to both sides.”

Indeed, in telephone interviews late today, Mr. Welch and other senior G.E. officers said that they would not have agreed to merge with RCA unless they were convinced that the two companies could be combined without a major change in RCA’s business or management style.

“This is a merger of two similar cultures; I don’t see any major conflict,” said Michael Carpenter, G.E.’s director of planning, who in the past has been an outspoken critic of the wave of mergers and acquisitions on Wall Street.

“My job is to give them the resources they need to win,” said Mr. Welch, who has pruned layers of middle-level management at G.E., closed down dozens of its plants and reduced overall employment by about 20 percent. At the same time, he has funneled more than $8 billion in capital spending into the automation, reorganization and growth of the company’s remaining businesses.

John F. (Jack) Welch Jr.

Even beyond the General Electric headquarters near here in Fairfield, Conn., Mr. Welch’s demanding style has become well known. A chemical engineer by training, Mr. Welch normally works 12-to-14-hour days in shirt-sleeves. He insists on fresh, entrepreneurial insight from his executives, often in spontaneous meetings.

Mr. Welch quickly changed things. The company’s planning department, under Mr. Carpenter, has shrunk to eight employees. And those who have left are among more than 100 employees at the Fairfield headquarters who have resigned, or been discharged, under Mr. Welch. About 600 remain.

EXCHANGE SEAT SELLS FOR $1 MILLION

A seat on the New York Stock Exchange was sold yesterday for $1 million, the highest price ever paid for what has become one of the hottest properties on Wall Street.

The record price eclipses the $850,000 paid for a seat only last Monday. Analysts said the sale showed confidence in the market’s strength in the face of the dollar’s weakness and interest-rate uncertainty.

Traffic and pedestrians in front of the New York Stock Exchange in 1987.

The New York Stock Exchange does not disclose the participants in the sale of a seat. But the buyer was identified on Wall Street as Stern Brothers, a small brokerage and specialist firm based in New York, and the seller was said to be Irwin Herling, a New Jersey resident.

Mr. Herling could not be reached for comment. In June 1964, when he was admitted to the exchange, four seats were sold, one for $205,000, one for $210,000, and two for $207,000. Officials at Stern Brothers declined to comment on the sale.

“The price of the seat reflects supply and demand,” said Richard Torrenzano, chief spokesman for the Big Board, as the New York Stock Exchange is known. “There is a great deal of demand right now, which seems to imply that we have reached the strongest level of optimism in our history about the strength and future of the New York Stock Exchange.”

There are 1,366 seats on the New York Stock Exchange, a number that has been fixed for decades, and 611 member organizations hold seats. Since seats are held in individual’s names, some firms hold several seats. Some seats may be leased, and some are held as investments.

AUGUST 4, 1987

SENATE, BY 91 TO 2, BACKS GREENSPAN AS FED CHIEF

The Senate today approved the nomination of Alan Greenspan to be the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.

Mr. Greenspan, who until recently ran his own economic consulting firm in New York, Townsend-Greenspan & Company, was approved by a 91-to-2 vote.

He will replace the current chairman, Paul A. Volcker, whose term expires on Thursday.

Voting against the nomination were Senator Bill Bradley, Democrat of New Jersey, and Senator Kent Conrad, Democrat of North Dakota.

Mr. Greenspan’s approval by the Senate was never seriously in doubt since President Reagan announced early in June that he would appoint the economist to succeed Mr. Volcker. But Mr. Greenspan’s views on deregulation caused some concern among senators, as did his close political ties with the Republican Party, and his lack of international exposure.

Senator William Proxmire, Democrat of Wisconsin and chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, on several occasions expressed his disagreement with Mr. Greenspan’s views that the banking industry should undergo considerably more deregulation. But Mr. Proxmire supported the nomination, noting that he expected Mr. Greenspan to be as vigorous an inflation-fighter as was Mr. Volcker.

President Ronald Reagan announcing Alan Greenspan (left) as Federal Reserve Board Chairman replacement for Paul Volcker (right).

STOCKS PLUNGE 508 POINTS, A DROP OF 22.6%; 604 MILLION VOLUME NEARLY DOUBLES RECORD

Stock market prices plunged in a tumultuous wave of selling yesterday, giving Wall Street its worst day in history and raising fears of a recession.

The Dow Jones industrial average, considered a benchmark of the market’s health, plummeted a record 508 points, to 1,738.74, based on preliminary calculations. That 22.6 percent decline was the worst since World War I and far greater than the 12.82 percent drop on Oct. 28, 1929, that along with the next day’s 11.7 percent decline preceded the Great Depression.

Since hitting a record 2,722.42 on Aug. 25, the Dow has fallen almost 1,000 points, or 36 percent, putting the blue-chip indicator 157.5 points below the level at which it started the year. With Friday’s plunge of 108.35 points, the Dow has fallen more than 26 percent in the last two sessions.

Yesterday’s frenzied trading on the nation’s stock exchanges lifted volume to unheard of levels. On the New York Stock Exchange, an estimated 604.3 million shares changed hands, almost double the previous record of 338.5 million shares set just last Friday.

Yesterday’s big losers included International Business Machines, the bluest of the blue chips, which dropped $31, to $104. In August the stock was at $176. The other big losers among the blue chips were General Motors, which lost $13.875, to $52.125, and Exxon, which dropped $10.25, to $33.50.

According to Wilshire Associates, which tracks more than 5,000 stocks, the rout obliterated more than $500 billion in equity value from the nation’s stock portfolios. That equity value now stands at $2.311 trillion. Since late summer, more than $1 trillion in stock values has been lost.

The losses were so great they sent shock waves to markets around the world, and many foreign exchanges posted record losses. In a sign of the continuing effect, the Tokyo Stock Exchange fell sharply today. The Nikkei Dow Jones average plummeted a record 3,395.95 yen, to 22,350.61, a drop of 13.2 percent, by late afternoon. Also, the Hong Kong exchange decided to close for the week.

Stock market analysts scrambled for explanations, which ranged from rising interest rates to the falling dollar to the possibility of war between the United States and Iran.

But many experts seemed to think that a major catalyst was fears of a breakdown in accords to maintain trading and currency stability between the United States and its major trading partners.

Stock prices around the world plummeted, taking their cue from Wall Street. Panic selling swamped stock exchanges in Tokyo, Hong Kong, London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Mexico City and other centers.

The stock market’s incredible decline, analysts said, might have repercussions far beyond the immediate ones. The stock market has often portended economic declines. What a decline such as has occurred may mean is hard to imagine.

Tens of millions of Americans are tied to the stock market, either directly, or through mutual funds, or through pension funds that invest in equities.

In addition, rumors began to spread yesterday that some financial institutions might have lost heavily in the frantic trading, and might be in trouble. Small firms may have liquidity problems, and be forced to close. Individual traders and investors have undoubtedly been wiped out. Large firms may have to cut back, and it is not inconceivable that the ripples may spread to the banking community, which has been edging into the securities business.

That could lead to layoffs, and further economic dislocations.

“One word is operative out there now,” said one very shaken trader. “Fright.”

A trader on the New York Stock Exchange bows his head during Black Monday.

THE MARKET PLUNGE

DAY TO REMEMBER IN FINANCIAL DISTRICT

From the trading floors of the big brokerage firms to the stock exchanges to the shoeshine stands in the heart of the financial district, it was clear that yesterday would be a day etched in people’s memories for years to come.

The genuine fear and panic rippling through the markets was reflected in the agitation of strangers stopping each other in the street to inquire about the market, in the stony-faced traders whose sense of humor had abandoned them and in the exhaustion of stock exchange employees struggling to maintain orderly trading.

Joel L. Lovett, a trader for Jacee Securities, stepped outside of the American Stock Exchange yesterday at the end of a session that eclipsed the 1929 crash and mopped the sweat from his forehead.

Wall Street workers heading home after the stock market crash.

“I’ve been down here for 30 years,” he said. “I thought pandemonium set in when John F. Kennedy was assassinated. But I’ve never seen anything like this. I thought there would be a correction in the market. But this is shocking. There’s hysteria and fear. It’s absolute fear.”

Normally calm offices needed lessons in crowd control. Investors lined up outside the Fidelity Investments office in Boston to redeem their shares, and passers-by stood in front of Fidelity Investments’ Park Avenue investors center in midtown Manhattan with their faces pressed against the glass even though there was nothing to see. The branch’s ticker tape had been broken for several days and the electronic bulletin board that had been flashing market quotes jammed at 1:56 P.M.

It’s absolute fear.

At midday, Craig Curtiss, an employee of Adler Coleman & Company who works on the New York Stock Exchange floor, observed: “Everything is out of control. Clerks and teletypists might be here till 7 o’clock.”

His firm trades 150,000 shares on a normal day. By noontime, it had already done half a million shares. “It’s crazy,” he said. He ordered a shish kebab from the hot-dog cart outside the exchange and asked for hot sauce just to “get a little more fire in the belly” before going back inside.

Wall Street traders are usually quick with the wisecracks following everyone else’s disasters, but the market’s unprecedented plunge yesterday left many of them with an unprecedented loss for words.

When somebody on Drexel Burnham Lambert’s trading desk asked if anyone had a joke to lighten things up, a bewildered pall fell over the usually glib crowd as the equities traders stared at each other blankly.

“This was not a laughing matter,” said Mark Mehl, head of Drexel’s equities desk. On second thought, he said, “I’d like to hear some jokes if you’ve got some.”

“Jokes?” said Jack Conlon, head trader at Nikko Securities. “Not a one. There’s nothing funny about what’s going on.”

Many traders and investment bankers expressed mock relief that most firms’ windows were sealed. Some Shearson Lehman Brothers traders posted a sign over their desk saying, “To the lifeboats.”

Wall Street Reviews ‘Wall Street’

For many investment banking luminaries at a private screening of “Wall Street” on Monday night, watching the new film was like watching home movies.

There were familiar deals and familiar faces, with cameo roles by pals and colleagues, in the movie about wheeling, dealing and crime on Wall Street. People in the audience at the uptown Manhattan theater nudged one another when Kenneth Lipper, the investment banker and former Deputy Mayor of New York, appeared on screen. They nudged each other again when Jeff Beck of Drexel Burnham Lambert came on.

There was an undercurrent of excitement in the audience, which included Bruce Wasserstein and Joseph R. Perella, co-heads of investment banking at the First Boston Corporation; Donald G. Drapkin, a lieutenant of Ronald O. Perelman, the chairman of Revlon Inc. and multimillionaire investor; Laurence A. Tisch, chief executive of CBS Inc.; and Paul E. Tierney Jr., the financier of Coniston Partners.

Long the grist for newspaper and society columns, Wall Street’s leaders had finally made it in Hollywood—even if it was as larger-than-life villains.

After the lights came up, many in the audience said they had found the movie, which opens tomorrow, dramatic and entertaining. And Stephen A. Schwarzman, a partner at the Blackstone Group, an investment banking firm, added: “The film captured the mood of the trading rooms. They tried to capture something about the deal-oriented side of Wall Street and they succeeded.”

Certainly the film is timely, coming in the wake of the insider trading scandals and the Oct. 19 collapse of the stock market. “Wall Street” is the story of a relentlessly evil Wall Street mogul named Gordon Gekko, played by Michael Douglas, who ensnares Bud Fox, an ambitious, and weak, young stockbroker, played by Charlie Sheen.

Mr. Fox courts Mr. Gekko’s business. Then Mr. Gekko easily seduces him into illegally gathering inside information for him. Mr. Fox, whose nose is pressed against the glass of the good life, is desperate to build his own fortune.

Ultimately, Mr. Gekko betrays him. Mr. Fox then comes to his senses and tries to rectify what he has done. In doing so, he incriminates Mr. Gekko.

Despite the audience’s enthusiasm, few were convinced that “Wall Street” would be a blockbuster, in part because its subject matter was too alien for many moviegoers.

As William E. Mayer, a managing director of First Boston, put it: “It’s too foreign to be a hit elsewhere in the U.S. You have people on farms in Iowa going to movies. How can they relate to this?”

The 130 people who attended the dinner at the Regency Hotel following the screening may have debated the merits of the film, which was directed by Oliver Stone. But most did not quibble with its technical accuracy.

“The screaming is typical,” Mr. Schwarzman said, referring to scenes in which deals started to go bad. “When deals go wrong, you have no one else to blame so you yell at yourself and you yell at others.”

At least one arbitrager, however, said the film captured the prevailing mood on Wall Street. “It laid bare the real motivations,” said this viewer, who requested anonymity. “People pretend that they are doing something noble, raising capital to support America’s businesses, but Wall Street is just about making money.”

Praise for the film was not universal. Mr. Drapkin, Revlon’s vice chairman, found the plot difficult to follow and said the story was not gripping. And he said the lack of a sympathetic character was a weakness.

“It is upsetting because it makes the excesses of Wall Street look like an everyday occurrence,” said Leonard N. Stern, chairman of Hartz, the pet food and real estate concern.

But given the damage already done by the insider trading scandal and the stock market crash, Mr. Schwarzman asked, “How can the image of Wall Street be hurt any more?”

Director Oliver Stone (right) sitting with actor Charlie Sheen on set of movie “Wall Street.”

MURDOCH’S GLOBAL POWER PLAY

A fiery-red lotus roars out of the driveway of the Bel-Air Hotel in Los Angeles. Knees tucked under the dashboard, Rupert Murdoch guns the low-slung two-seater through the twisting turns on Stone Canyon Road—simultaneously shifting, steering and tracking down his subordinates on the car telephone. At precisely 8 o’clock on this balmy January morning, the Lotus rolls through the gates of 20th Century-Fox, Murdoch’s television and motion picture studio.

Media baron Rupert Murdoch in his office in 1985.

Murdoch storms into his office, his double-breasted blazer flapping, and confronts the stacks of letters and faxes on his mahogany desk. They are the outpourings of the News Corporation Ltd., a $4.2 billion global empire that encompasses 150 newspapers and magazines, a satellite cable channel, book publishers, an airline, television stations, a hotel reservation service, even a sheep farm in the Australian outback. Normally, Murdoch would devour these documents, but he impatiently shoves them aside. He wants to concentrate all his considerable energies and anger on the target of the day: Senator Edward M. Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts.

At Kennedy’s urging, a special measure had quietly been attached to a catchall spending bill and signed into law. It closed the door on any chance Murdoch might have of escaping a Federal ban against cross-ownership of newspapers and television stations in the same city—in his case, The Boston Herald and WFXT-TV, in Boston, and The New York Post and WNYW-TV, in New York. “The process was an outrage,” says Murdoch, his hard-edged Australian vowels asserting themselves. He calls it an exercise in “liberal totalitarianism,” an attack against papers that have frequently criticized the Senator.

Over the next days, Murdoch will mount the kind of brass-knuckle attack that has made the Melbourne-born publisher the most intimidating media mogul since William Randolph Hearst. “People are afraid of him,” says Sir William Rees-Mogg, former editor of The Times of London.

In an era when giant corporate and financial institutions increasingly compete on a worldwide basis, Keith Rupert Murdoch stands poised to create the first global communications network. The pieces are already in place on four continents.

His newspapers control 60 percent of the market in Australia, more than a third of the market in Britain. The South China Morning Post, his toehold in Asia, commands the lion’s share of Hong Kong’s English-language newspaper circulation. He owns television or cable operations in the United States and Europe, upscale magazines such as New York and Epicurean in Melbourne and major interests in book publishing houses such as William Collins Sons & Co. in London and Harper & Row in New York. He has a significant financial stake in Reuters, the international news service, and in Pearson P.L.C. of London, whose holdings include The Financial Times and the Penguin Publishing Company.

The News Corporation’s revenues have grown at a startling pace, driven by a 10-year string of acquisitions. But its debt has mounted even faster; it has reached $5.6 billion—$4.3 billion in direct borrowings, plus an additional $1.3 billion in convertible debt. The company’s huge cash flow easily services that debt and enables News Corp. to take on more.

Deft exploitation of the differences in Australian, British and American tax and accounting rules permit the company to borrow far more than its competitors while avoiding dilution of Rupert Murdoch’s holdings. Through such borrowings, Murdoch has extended his realm, one giant step at a time:

A. In March 1977, after snapping up The New York Post for $30 million, he purchased the New York Magazine Company for $17 million.

B. In Feb. 1981, he gained control of the venerable Times of London and The Sunday Times for $28 million.

C. In April 1985, he purchased 50 percent of 20th Century-Fox from Marvin Davis, the Denver oilman, for $250 million and soon after secured seven television stations from Metromedia for $2 billion. In December, Murdoch bought Davis’s remaining share of Fox for $350 million.

D. In March 1987, he took over Australia’s Herald and Weekly Times group for $1.6 billion, and then Harper & Row, the publisher, with a $300 million offer.

E. In Jan. 1988, he revealed a $600 million, 20.4 percent, holding in Pearson P.L.C., owner of The Financial Times, making the News Corporation the largest shareholder.

Bid for RJR Nabisco Jolts Bonds

The corporate bond market was jolted yesterday by the $17 billion leveraged buyout offer for RJR Nabisco.

The movement in RJR bonds was merely the latest takeover-related drop that has occurred this week. Earlier, prices of outstanding Philip Morris securities fell sharply after the company made an unsolicited offer for the Kraft Company.

“Over the last 30 days or so it has become increasingly obvious that there is an increasing level of event risk in the bond market because stock market prices are so low,” said James Ednie, corporate vice president and senior industrial corporate bond trader at Drexel Burnham Lambert. “Bondholders suffer from those sorts of transactions, because securities become increasingly attractive to raiders and management. It is clear that the industrial bond market cannot benefit from this deal.”

Underscoring Mr. Ednie’s point were the actions taken by the two major ratings services, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, in the wake of the RJR announcement. Yesterday afternoon both agencies said they were monitoring the company and suggested that ratings might be downgraded on RJR’s $5 billion in outstanding debt. The company currently is rated A by both services.

The ripples that spread from the RJR announcement were big enough to overcome a rise in the secondary Treasury bond market and caused prices of many other industrial bond issues to ease by about one-quarter of a point, traders said.

SEPTEMBER 8, 1988

DREXEL BURNHAM CHARGED BY S.E.C. WITH STOCK FRAUD

The Securities and Exchange Commission charged yesterday that Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. had engaged in a secret agreement with Ivan F. Boesky to defraud Drexel clients, trade illegally on insider information, manipulate the prices of stocks and violate a host of other securities regulations.

Although some of the charges against Drexel, one of Wall Street’s most powerful firms, had been anticipated for some time, the nature of other allegations were more serious than had been generally expected.

The 184-page civil complaint, filed in Federal District Court in Manhattan after the stock markets closed, named Drexel and four of its employees, including Michael Milken, the head of the firm’s high-yield “junk bond” department. The complaint recounts Drexel’s role in a litany of high-powered corporate mergers and restructurings involving such names as MGM/UA Entertainment, MCA Inc., Diamond Shamrock, the Wickes Companies and the Stone Container Corporation.

In its filing, the agency accused the Miami industrialist Victor Posner and his son Steven N. Posner of violating Federal securities laws by scheming with Drexel to conceal the ownership of securities, an illegal practice known as stock parking.

While the complaint does not spell out precise fines, S.E.C. lawyers said yesterday that if they were successful Drexel could be penalized hundreds of millions of dollars.

In addition, all the defendants could be forced out of the securities business after an administrative proceeding, which typically follows cases brought by the S.E.C.

Mr. Boesky has been a crucial element of the Government’s investigation of Drexel, and he is expected to be the star witness for the S.E.C. and Federal prosecutors if their cases make it to trial.

OCTOBER 31, 1988

KRAFT BEING SOLD TO PHILIP MORRIS FOR $13.1 BILLION

In one of the biggest takeovers to date, two of the nation’s best-known makers of consumer goods, Philip Morris Companies and Kraft Inc., yesterday agreed to merge in a deal valued at $13.1 billion in cash.

Kraft’s stockholders will get $106 a share, $9.50 higher than the shares closed on Friday and $40.875 higher than they were trading for before the offer was made on Oct. 17.

The combined company would knock Unilever, the British-Dutch company, out of first place as the world’s largest producer of consumer goods.

In making the announcement late yesterday with Kraft, Hamish Maxwell, chairman and chief executive of Philip Morris, said: “As we have stated from the outset, we believe the combination of Philip Morris and Kraft will create a U.S.-based food company that will compete more effectively in world food markets. Kraft’s products provide an excellent complement to our existing product lines and position us to capitalize on marketing opportunities worldwide.”

Philip Morris is the maker of Marlboro cigarettes, Miller beer, Maxwell House coffee and Ronzoni spaghetti, among other products. In addition to Kraft cheeses, including Philadelphia and Velveeta, Philip Morris will now add such other well-known Kraft brand names as Sealtest ice cream, Parkay margarine, Light n’ Lively yogurt and Miracle Whip salad dressing.

Kraft executives and employees may not see much change in the combined company, except for the new ownership. Mr. Richman will remain Kraft’s chairman and also become a Philip Morris vice chairman. Michael A. Miles, Kraft’s president and chief operating officer, will remain president of Kraft but take on the additional title of chief executive officer, continuing to report to Mr. Richman. Philip Morris and Kraft have also agreed that Kraft’s headquarters will remain in Glenview, Ill., for at least two years.

Kraft’s enormously valuable name will survive as a subsidiary of Philip Morris while the Philip Morris parent company will continue to operate as it did before.

Asked in an interview if he had any more takeover deals in mind, Mr. Maxwell said with a chuckle, “No, this is enough for this year.”

MARCH 5, 1989

TIME INC. AND WARNER TO MERGE, CREATING LARGEST MEDIA COMPANY

Time Inc. and Warner Communications Inc. announced yesterday that they plan to merge, creating the largest media and entertainment conglomerate in the world.

Time’s chairman, J. Richard Munro, said the new company would seek to grow even larger by acquiring other businesses.

Time is a leading book and magazine publisher with extensive cable television holdings, and Warner is a major producer of movies and records and has a large cable-television operation. The merger would create a new company, Time Warner Inc., with a stock market value of $15.2 billion and revenue of $10 billion a year.

The merger would insure Time Warner a place in the 1990’s as one of a handful of global media giants able to produce and distribute information in virtually any medium. The companies said the deal would help the United States compete against major European and Asian companies.

“Only strong American companies will survive after the formation of a unified European market in 1992,” said Steven J. Ross, chairman of Warner.

Time Warner would replace Bertelsmann A. G., a privately held German publisher known primarily for its book division, as the world’s largest communications company in terms of revenue. Bertelsmann’s 1987 revenue was more than $6 billion.

The merger would unify two huge media companies that have felt the pressure of demands for performance and have long been the subjects of takeover rumors on Wall Street. The much larger merged company would be a more difficult takeover target.

An analyst for Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., John Reidy, called the deal “mind-boggling.”

“What you’ve got is a company that will be the largest magazine publisher in the country, the world’s most profitable record company, a cable television entity with more than 5.5 million cable subscribers, one of the world’s largest book-publishing operations and the country’s largest supplier of pay-cable programming,” he said.

Time’s properties include Time, People, Money and Sports Illustrated, as well as Home Box Office, the pay-television operator; Time-Life Books, and Book-of-the-Month Club.

Warner owns Warner Bros., a major film producer, and a large record company, a major paperback book publisher and cable-television systems.

One person who attended the Time board meeting said that after a day of reviewing financial data, board members applauded when shown a video of Warner programming, including excerpts from its new “Batman” movie.

Michael Milken: Legendary Wall Street Outsider at Center of U.S. Inquiry

One of the few things the highly competitive and often contentious executives in the financial world can agree on is that the 1980’s would have been a different era were it not for the energy and obsession for control of one person: Michael R. Milken.

Certainly Drexel Burnham Lambert would not have been in the position of forfeiting $650 million to settle securities law charges were it not for its involvement in activities overseen by Mr. Milken’s area of operations.

By extolling the rewards of high-yield “junk bonds” over their risks, Mr. Milken promoted a market that now amounts to $175 billion. In the process, his firm raised billions of dollars in capital for young companies and helped fuel the takeover boom with deals financed by junk bonds. At the same time, though, Mr. Milken’s unorthodox sales practices and network of investors raised serious questions about the propriety of his techniques.

One would never guess at Mr. Milken’s almost legendary image by looking at him.

Mr. Milken is self-effacing and modest in appearance. He favors sport coats over suits and wears a less than subtle toupee, providing a thatch of dark hair over his boyish face and deep-set, dark eyes.

He has also cultivated an image as an outsider. Mr. Milken once labored in something close to obscurity out of an office in Beverly Hills, Calif., near where he grew up but about as far from Wall Street as one could get.

That was the facade. Behind it was a man whose intense, slightly high-pitched voice over a telephone could cause some of the flashiest, wealthiest and most powerful financiers to snap into action and do precisely as he directed, whether it was buying tens of millions of dollars of junk bonds issued by one of his clients or helping finance a takeover. That, in fact, was Mr. Milken’s real genius and possibly the cause of his downfall. It was not what he did with his own money, or even the way he singlehandedly created the junk bond market, but the network of wealth he could marshal to consummate the deals he dreamed up.

Michael Milken being questioned by reporters in 1998.

It was an awesome financial force that he orchestrated with the deftness of a philharmonic conductor. It was also a network that no other Wall Street firm could match, or crack, and that Government investigators spent two years trying to unravel.

Mr. Milken worked not with the Fortune 500 companies that make up the corporate establishment, but with entrepreneurs like Nelson Peltz, Ronald Perelman, Ivan F. Boesky and T. Boone Pickens, who were little known before Mr. Milken’s junk bond revolution was unleashed in the early 1980’s.

Mr. Milken was able to turn his clients into multimillionaires. He also made certain that they understood just who was responsible for producing that bounty, creating powerful allegiances that he could call upon when needed.

And Mr. Milken was more than just a financier, say those who worked closely with him. He was, they say, a salesman with an unequaled ability to make those in his financial orbit feel they were part of a mission, with his inspired sermons on the power of junk bonds.

At the heart of the legend was what many called “the Milken experience.”

In his heyday, this is the way it typically worked. The chief executives of three to seven companies would be sent to different conference rooms in Mr. Milken’s Beverly Hills office.

Surrounded by a phalanx of aides, Mr. Milken would march from one room to the next, delivering in each an inspired discussion of the chief executive’s company, its prospects, its needs and what Drexel would do for it.