In the little-seen film “Rude Awakening,” released in 1989, two former hippies return to the New York of the 1980’s and discover a new America in which idealism has given way to materialism and political protest has vanished. In one telling scene, three icons of the era—Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale and Timothy Leary—argue over a business deal. The revolution was truly over.

The voyages of self-discovery and personal fulfillment that typified the 1970’s, dubbed the Me Decade, reached their final stops by the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s first term. As baby boomers reached their thirties and forties, the itch to acquire took hold. The years of recession and inflation receded, giving way to an economic boom that encouraged wealth accumulation and conspicuous consumption.

The style setters of the Reagan era provided a marked contrast to the muted tones of the Carter administration. Nancy Reagan, surrounded by an entourage of California tycoons and their wives, cultivated a court style that favored designers like Adolfo, James Galanos and Bill Blass.

Glitter and display ruled the upper reaches of Manhattan’s social world as well. Wall Street wealth translated into a nonstop pageant of charity balls, A-list receptions at the Temple of Dendur in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a fevered competition to serve on the boards of the best museums. The new money launched the careers of society decorators like Mark Hampton and Mario Buatta, known as the Prince of Chintz for his lavish use of floral patterns.

Ronald Reagan And Nancy Reagan

Fashion was on the move, speaking in unfamiliar accents and drawing inspiration from unexpected sources. A new generation of Japanese couturiers emerged, led by Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, captivating fashion critics with designs that recalled abstract geometric paintings.

At the same time, street fashion influenced style every bit as much as the runway shows in Paris and Milan did. Stars like Madonna picked up on the clothing trends in Manhattan nightclubs, then displayed them to an audience of millions through the new medium of music videos. Suddenly, teenagers wanted to wear fingerless lace gloves, crucifix jewelry and underwear as outerwear. California mall rats invented the Valley Girl look. Later in the decade, rap music and hip-hop brought the street styles of Harlem and L.A.’s South Central neighborhood to eager fans.

The fitness boom, reflected in the popularity of Jane Fonda’s phenomenally successful “Workout Book,” had a profound influence on fashion, forcing designers to rethink the female body and the changing social role of women. Azzedine Alaïa made his name with body-hugging dresses that earned him the nickname King of Cling, while Claude Montana came up with one of the decade’s signature looks: big shoulders and tight waists that endowed the female form with a linebacker’s power.

Fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, fashion designer Oscar de la Renta, actress/singer Liza Minnelli and actress Audrey Hepburn ay a reception at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1989.

Most women did not buy Alaïa or Montana. Their designers were Calvin Klein and Donna Karan. They learned to love the big-shoulder look by watching the hit television series “Dynasty,” where Hollywood designer Nolan Miller outfitted Linda Evans and Joan Collins with shoulder pads that seemed to take up the entire screen. Films like “Flashdance” popularized fitness fashion—dance-rehearsal clothes like leg warmers and sweatshirts, or tracksuits.

The women from the cast of “Dynasty” show off their shoulder pads.

Commercial fashion relied on advertising and marketing, not couture shows. Calvin Klein became a household name thanks to a series of brilliant advertising campaigns for his jeans, featuring models like Brooke Shields and Andie MacDowell and directed by fashion photographers like Bruce Weber and Richard Avedon.

Men got their taste of casual glamour from shows like “Miami Vice,” where Don Johnson wore T-shirts under unconstructed jackets, voluminous pleated linen trousers, loafers without socks, Ray-Ban Wayfarers and lots of pastel.

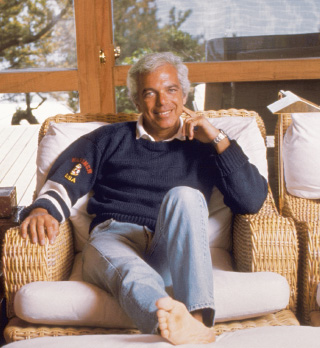

More conservative buyers opted for the preppy look, a reinterpretation of old-guard establishment style championed by Ralph Lauren, a former Brooks Brothers salesman. The impulse was international. In Britain, it was favored by the tribe known as the Sloane Rangers, epitomized by Diana Spencer, a Sloane icon before her marriage to the Prince of Wales. In France, the look was known as “bon chic, bon genre”—or BCBG, for short.

Americans wanted to live well, and Martha Stewart sympathized. Her first book, “Entertaining,” published in 1982, catered to the same fantasies of the good life as did Ralph Lauren’s clothing designs. Every generation requires an official guide to good taste and gracious living. Stewart stepped into the role in the 1980’s, addressing a surprisingly broad audience. Kmart, sensing Stewart’s mass appeal, signed her up to produce a signature line for its bargain-priced stores.

Food and fine dining, once the preoccupation of a small eccentric subculture, began to attract large numbers of the affluent, pleasure-seeking tribe known as yuppies, who haunted the latest restaurants and swore allegiance to fine wine. The food revolution that began in California at Chez Panisse gathered steam, and a new American cooking style emerged. Chefs like Paul Prudhomme and Larry Forgione showed the potential of traditional American ingredients and regional styles. France no longer dominated the culinary conversation.

A sample meal at Chez Panisse.

The appetite for good food coexisted, sometimes uneasily, with a strict mandate handed down by fashion magazines and advertisers: be thin. A rash of diet books and workout manuals showed how to stay svelte and toned all the way to old age. The federal government came to the rescue when the FDA approved a new artificial sweetener, aspartame. Lean Cuisine, introduced in 1981, tapped into a growing market when it offered low-calorie frozen meals. The American waistline continued to expand regardless.

Nintendo’s Game Boy was introduced in 1989.

Video games did not help. Children who, in days of yore, would have played sports instead spent their time with arcade and computer games like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and Super Mario Brothers. Rubik’s Cube, a puzzle with moveable parts, required a certain amount of manual labor, but its heyday was brief. The expansion of cable television made it even more difficult to move from the couch.

What you saw depended on where you stood. The same America that witnessed an alarming dramatic rise in cocaine use among the middle classes also experienced a revival of evangelical Christianity, a conservative shift that would dramatically reshape national politics for years to come. In the end, there was only one thing that Americans could agree on in the 1980’s: when the Coca-Cola Company, with great fanfare and a marketing blitz, introduced New Coke in 1985, the public rejected it unanimously.

NOVEMBER 5, 1980

THOSE PRECOCIOUS ADS

He has winsome brown eyes, she has tumbling blond curls, and neither of them is a day over 11 years old. “You’ve got the look I want to know better,” he sings to her. Leaning toward him intently, she sings back, “You’ve got the look that’s all together.”

The “look” is Jordache jeans for children, and the 30-second television commercial is an example of a new—and highly controversia—generation of advertising. While advertisers have long exploited sex and youth to sell their products, recently they have begun to pitch that appeal to ever-younger markets. In the last few months, it is widely believed, there has been an explosion in sexually suggestive commercials using child models and aiming at the prepuberty set.

One of the most controversial series of commercials, for Calvin Klein jeans, is actually aimed at adults but features a 15-year-old film star, Brooke Shields, who made her debut a few years ago as the nymphet of “Pretty Baby.” In the seven commercials, the teenager is given such double-entendre lines as “What comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing!” and “If my Calvins could talk, I’d be ruined.”

Fifteen-year-old Calvin Klein model Brooke Shields in 1980.

Such commercials have offended a number of adult viewers. “We’ve been getting an awful lot of letters from all over the country,” said Evelyn Dee, a staff member of Morality in Media, an antipornography group. “A lot of people think Brooke Shields is being exploited.”

Manufacturers acknowledge that they also have received protests, but they note that it is hard to quarrel with the commercials’ apparent success. “We got a negative reaction,” said Warren Hirsh, former president of Puritan Fashions, which manufactures Calvin Klein jeans. “But I’ll be frank: Our business was quite good.”

JANUARY 21, 1981

WITH A NEW FIRST LADY, A NEW STYLE

When her husband was inaugurated as the 39th President, Rosalynn Carter decided not to buy a new gown for the ball; she wore an old blue chiffon she had purchased six years earlier and worn for Mr. Carter’s inauguration as Governor of Georgia.

Nancy Reagan chose a single-shoulder James Galanos gown for the 1981 inaugural ball.

After Ronald Reagan became the nation’s 40th President yesterday, Mrs. Reagan prepared to appear at the inaugural balls in a handbeaded gown designed by James Galanos. Its cost is estimated by industry experts to approach five figures and the overall price of Mrs. Reagan’s inaugural wardrobe is said to be around $25,000.

Such differences bring into sharp focus the contrast between Mrs. Carter’s style and that of Nancy Reagan, who is already being hailed by some as a glamorous paragon of chic and criticized by others for exercising her opulent tastes in an economy that is inflicting hardship on so many.

Fashion designers are ecstatic about Mrs. Reagan’s emphasis on clothes and effusive in their descriptions of her personal style. “She represents what I would call a thoroughbred American look: elegant, affluent, a well-bred, chic American look,” said Adolfo, one of Mrs. Reagan’s favorite designers. “She has very feminine taste, but not cute, not frumpy. If she has a blouse with a little ruffle, it’s elegant, it’s not overbearing. She herself is more important than what she has on. She has expensive taste, but it’s an image of good taste. I think there are many women who would like to look like her.”

Many fashion figures expect the impeccably groomed Mrs. Reagan to stimulate their industry. “She’s going to have a great influence on fashion,” said Mollie Parnis, who has designed clothes for every First Lady in the past thirty years, although she has not yet designed anything for Mrs. Reagan. “She likes clothes, she entertains beautifully, she will be wearing the right thing at the right time, and it has to filter down.”

JULY 6, 1981

An Abundance of Hair on City’s Streets

Hair—the real thing, not the musical—is having a big revival this summer. What seems to be tons of hair can be seen bouncing around the city, more of it than has been fashionable for decades.

Hair was long in the 1940’s when Rosie the Riveter was required to wrap it up in a scarf so she wouldn’t get tangled in the production line machinery. It was long again in the hippy 60’s, but then it was either ironed straight or frizzed into Afros. This year, it is long and wildly curly and the woman with a wealth of tresses is stopping traffic on the city streets.

The naturally curly-haired woman is, of course, especially blessed. But for her straight-haired sisters, there is always the beauty salon. Hairdressers are dusting off techniques they haven’t used in years: setting hair on rollers, or rag curlers, or contraptions that look like twisted macaroni.

Teasing—it’s called back combing these days—is back. And hair stylists sometimes cheat for photography by using l960’s fake “falls” or propping hair up with horsehair “rats.” Salons are reporting a brisk business in permanent waves to give hair the body required for the current effects.

What women say they like best about longer hair, in addition to the fact that it goes with this year’s luxurious, sexy fashions, is the possibility of variations. Madeline Stone, a songwriter, explained that she was born with curly hair. “I don’t do a thing to it after I wash it,” she said. “I’m so glad to be in fashion again.”

THE DRESS:

Silk Taffeta with Sequins and Pearls

LONDON, July 29–For her long walk up the aisle that transformed her into a princess, Lady Diana Spencer, in the most romantic storybook tradition, wore a sequin-and-pearl-incrusted dress with a 25-foot train.

Made of ivory silk taffeta produced by Britain’s only silk farm, the dress was hand-embroidered with old lace panels on the front and back of the tightly fitting boned bodice. A wide frill edged the scooped neckline, and the loose, full sleeves were caught at the elbow with taffeta bows. A multilayered tulle crinoline propped up the diaphanous skirt.

A diamond tiara belonging to Earl Spencer, Lady Diana’s father, anchored her ivory tulle veil, aglitter with thousands of hand-sewn sequins. Also borrowed was a pair of diamond drop earrings from Lady Diana’s mother, Frances Shand-Kydd.

For the final tradition-bound item -something blue—a blue bow was sewn into the waistband of the dress. A fiercely and successfully kept secret, the dress had been guarded day and night by a security organization at the workrooms of the designers, David and Elizabeth Emanuel. A final fitting, necessitated by Lady Diana’s loss of 15 pounds in the last four weeks, was held last week at Buckingham Palace. Emmanuel-designed wedding dresses sell for about $3,700 at Harrods, the London department store. But a dress manufacturer in Cardiff, Wales, had already produced two copies of the gown by 4:30 P.M. today. In three days, the company said, it will make 90 more copies selling for $500.

Queen Elizabeth’s dress, coat and hat, by Ian Thomas, were bright acquamarine crepe de chine, worn with a double strand of bird’s-eggsized pearls and a large diamond brooch. Festooned with a fluffy hat of osprey feathers, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother chose vivid sea green silk georgette with floaty panels by her favorite designer, Hartnell. Princess Anne and Princess Margaret were both colorful, the former in a white dress with buttercup yellow flowers, the latter in deep peach georgette.

A popular choice was cornflower blue, now being called “Lady Diana blue” after the suit she wore in her widely published engagement photograph. Mrs. Shand-Kydd, Princess Alexandra and the Princess of Wales’s former roommates chose similar shades of blue, as did the Countess Spencer, stepmother of the Princess, and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

NANCY REAGAN GIVES UP DRESS DESIGNER LOANS

WASHINGTON, Feb. 16–Do clothes make the woman? Not necessarily. Not when they are expensive designer gowns on loan to the White House. Not when they stir a public controversy. Not when the First Lady is involved.

Hurt by public criticism of her practice of accepting expensive dresses and later giving them to museums, Nancy Reagan has found a graceful way out. She is phoning her designers and is also informing the general public that she will no longer accept loans of clothes from fashion designers.

In the last few days, the White House has sent out nearly 40 letters to people who have written to comment, both positively and negatively, about Mrs. Reagan’s acceptance of dresses from designers such as Galanos, Adolfo, Bill Blass and David Hayes and then donating 13 of their dresses to museums.

She felt she was helping the American clothing industry

“She really just got tired of it all, of people misinterpreting what she was doing,” said one close personal aide who requested anonymity. “She felt she was helping the American design industry and the American clothing industry by publicizing American fashions. But it was beginning to take a bad slant, as if she didn’t have any wardrobe of her own, which is ridiculous. It got to her.”

The letter, signed by the First Lady’s special assistant, Elaine D. Crispen, explains that for many years in California as well as in the White House, Mrs. Reagan has given her clothing to museums “because she believes that the clothing of any particular era is a visual story of the people of that period.”

And, in response to some public suspicions, the letter emphasizes that in the past, “neither she nor the designers have taken a tax deduction” for the donated dresses.

JULY 31, 1983

MUCH ADO ABOUT THE JAPANESE

The commotion is widespread, though the clothes are just beginning to be. They come from Japan and involve, in particular, the work of three designers born, bred and trained there: Issey Miyake (say me-yak-ee), Rei Kawakubo (ray cow-wa-coo-bo) and Yojhi Yamamoto (Yo-ge ya-ma-mo-toe). Though there are several other talents whose designs are spreading commercially—among them Matsuda and Kansai—it is this trio that is spearheading a startlingly original fashion movement.

THE COMMOTION IS WIDESPREAD

It is a movement that has an established foundation: Miyake has, since 1972, been presenting collections in Paris or New York and selling to a few avant-garde boutiques, among them Charivari in New York. But it is only in the last year or so that the Japanese movement has gained momentum, as Miyake has been joined by fellow countrymen in introducing their collections at the widely attended and reported pret-a-porter showings in Paris.

Last March, at the presentations for fall 1983, the Japanese look suddenly was very apparent, almost overshadowing the rather mild French offerings. As a result, it made headlines, conversations and controversy. The Japanese had “arrived” and fashion-conscious customers everywhere were extremely curious to know and see all about the movement.

But fashion followers, critics and store buyers seem to be split in their opinions. Either the Japanese movement is the most exciting thing to happen to fashion in years, or it’s an outrage, a travesty of what clothes are supposed to be about. The believers of the latter are dismayed at such things as sweaters sprouting holes, albeit carefully calculated ones; at coats and dresses cut with slits here and there and hemlines that dip down and up in a seemingly haphazard way; at sleeves that slip well down over the hands and sometimes come four to one garment. They cannot conceive of women wanting to engulf themselves—most of these clothes are cut on the voluminous side—in something so strange, so never before seen.

Understandably, the big American department and specialty stores have moved very cautiously in investing money and space in something so violently at odds with the rest of today’s fashion picture that is safe and predictable. It is still not easy for the curious customer to locate the new Japanese clothes in these big stores, even in one as forward-thinking as Bloomingdale’s.

Yet these qualities of newness, strangeness, inventiveness, of surprisingly fresh thinking are drawing an ever-increasing number of admirers to the Japanese designs. This Japanese infusion—or intrusion, depending on the viewer’s interpretation—is serious and far-reaching. It questions what is balance and symmetry and what is drama and sophistication. What these clothes—particularly those of Miyake and Kawakubo—possess above all else is strength and elegance. They are never unsure, or, for that matter, flamboyant. And while they certainly do not satisfy accepted Western standards of coquetry and allure, they establish their own vocabulary for initiating the same emotions.

The young, with their sense of adventure, are also drawn to these Japanese designs, often despite their high price. Karl Lagerfeld, Paris’s premier avant-garde creative talent, has commented that the new fashion for the 1980’s “will come from the Japanese.… They are so much better educated for the future. They can be happy in a changing world. They don’t compare clothes to the past as we do. They want the future.”

ON THE TRAIL OF LONDON’S SLOANE RANGERS

Caroline is squeaky clean, freshfaced and easy to identify by the string of (real) pearls, which she wears at all times. Henry is cleancut and pink-cheeked, and can be spotted from a distance by his too-large coat (handed down from his father). Closer inspection will reveal either a red- or blue-and-white boldly-striped shirt (during business hours) or a good, plain, but frayed, one (in off-duty hours). Both are Sloane Rangers.

Sloane Rangers have been a distinct species for years, but it took two journalists, Anne Barr and Peter York, to come up with the collective noun—and Caroline and Henry as the archetypal names—a few years ago. Official recognition came with the publication of their “Sloane Ranger Handbook” just over a year ago and, more recently, the “Sloane Ranger Diary.”

Visitors to London wishing to study the breed should simply take a walk through Sloane Ranger land—known to the Post Office as the SW 3,5,7 and 10 districts, and to the general public as Knightsbridge, South Kensington and Chelsea—where they will find them thick on the ground: at work, rest and play in their natural habitat.

Sloane Rangers congregate there because they feel safest among their own kind. Named for Sloane Street and Sloane Square, the hub of their universe, Rangers are upper-class men and women who come “up from the country” to live in London after finishing school or university. Their object is marriage. By definition, they are young for, once married, they may stay in town until the first little Sloane arrives, but then it’s back to the country, Land Rover and Labrador.

In the meantime, most work (although the women will stop as soon as possible after the wedding) and most share flats, as the Princess of Wales did. “POW,” as the Princess is known among those who used to be her peers, is Super Sloane and the fashions she set during her engagement were simply the standard Sloane Ranger uniform. She has progressed, but they have stayed the same. Sloane Rangers are conservative, conventional and insular.

To see them in their greatest concentration, if time is limited, walk down Beauchamp (pronounced Beecham) Place past one bijou boutique after another. Caroline will have a mane of thick (but manageable) hair, held back perhaps by a 1960’s velvet-covered hairband. There will be a Hermes scarf somewhere in evidence (perhaps tied around the strap of her shoulder bag). In winter, she will be wearing a Loden coat; in summer a dress (probably Liberty print). The sportif Caroline will wear a lambs-wool crewneck sweater in a clear color with the lace collar of a blouse turned over it. She may wear jeans or a skirt in navy, burgundy or olive with colored pantyhose and low-heeled Gucci shoes.

Henry will be wearing a bespoke suit, dotted tie and silk handkerchief (probably also spotted). Or, perhaps, he will sport his casual garb: jeans, decent tweed jacket and either a navy Guernsey or olive army sweater; sometimes he will brighten the outfit with a yellow pullover.

Princess Diana, Sloane Ranger, in 1982.

JUNE 7, 1985

Madonna and Her Clones

Madonna at the 12th Annual American Music Awards in 1985.

She uses only one name, but no matter. Only those who have been residing on the planet Jupiter for the last several years need to ask Madonna who? Rock’s hottest female star, whose hits include “Borderline,” “Material Girl” and “Like a Virgin,” is in New York for performances at Radio City Music Hall and Madison Square Garden.

She is leaving her mark not only on popular music but on popular style as well. Madonna’s style of dress might best be characterized as part Jayne Mansfield, part street urchin. It emphasizes a low neckline and, often, a bare midriff, lace tights, anklets, thrift-shop jewelry, fingerless lace gloves and more.

How much more? Well, flower-print tight pants, a gold crucifix, Merry Widow black lace bras, chiffon strips as hair bows and jeweled belts. A tumble of disheveled curls tops it all off.

For those who want a little historical perspective, the popularity of this mode has been traced all the way back to 1983, when Cyndi Lauper, a rock star with a sense of humor, first put all the pieces together. But while Miss Lauper carved out a niche for the look, Madonna has turned it into a bona fide fad, taken up by legions of adolescents and post-teenagers such as those below.

This week, Madonna, left, was windowshopping on Madison Avenue, ice cream in hand, a camera-shy bodyguard at her side, and typically decked out. Her ensemble included tight flower-print black pants, Merry Widow top, bare shoulders, assorted rosaries and sunglasses. The girl had all her material.

NOVEMBER 13, 1985

Fashion Experts Rate Princess’s Style

From the moment Princess Diana landed on American soil, the big names of America’s fashion world were watching. As usual, they found little to agree on but this: “She is,” said Lynn Manulis, president of Martha, “the most charismatic fashion figure that’s come down the pike since Jackie O.”

Diana’s clothing choices are, of course, limited by royal protocol. But Evangeline Bruce, who sat next to Prince Charles at the National Gallery dinner in Washington Monday night, said, “I have the feeling the title bit doesn’t come into her dressing.” Mrs. Bruce is the widow of David K. E. Bruce, who was Ambassador to Britain.

Diana’s style gave some fashion arbiters pause, though their criticism was often couched in awe. “She is just an overwhelming personality,” said Geoffrey Beene. “It doesn’t matter what she wears. I don’t think the clothes are that good, some of the design is not on target to me as a professional, but who cares? Her presence overcomes any banalities of dress.”

Like the winds that kept Diana clutching at them, some blew cold over the Princess’s hats. “I just think they’re terrible,” said Eileen Ford, co-founder of Ford Models.

The designer Mary McFadden disagreed. “I love her flying saucer hats,” she said.

Michael Katz, another designer, joined in Miss McFadden’s approval. “I don’t like all of them,” he said, “but it’s good and it’s new.”

While no observer was willing to call Diana a pacesetter, some thought there were lessons to be learned from her wardrobe. “The essence of being well dressed is to be appropriate for every occasion,” said Amy Levin, editor of Mademoiselle. “She does that. Maybe her things could be a little bit racier or more modern, but I think she’s great.”

Diana, Princess of Wales, wearing a red silk taffeta evening dress designed by fashion designer Jan Van Velden.

“I don’t know what appropriate means,” said Grace Mirabella, the editor of Vogue. “You’ve got a 23-year-old who is in a special place, so appropriate becomes rather different.” She found the Princess “marvelous” in gowns, but thought her days clothes seemed “a little less than glamorous.”

“There’s nothing dowdy about her,” Diana Vreeland said. “She’s got radiance. What she wears is incidental but she has wonderful taste. Aura is everything. It’s the essence of the woman. You can buy the town out and not get off the ground, but if you’ve got the personal aura, you just shine, you give pleasure.”

Indeed, Diana gives pleasure, but the key may not be her clothes. “It’s difficult for her not to look well,” said Bill Blass. “Her youth counteracts her clothes. You don’t notice her clothes as much as her. There’s a lot to be said for youth, kid.”

THE MAKING OF A DESIGNER

Tommy Hilfiger is headed for the top—just ask him.

“I think I am the next great American designer,” he said. “The next Ralph Lauren or Calvin Klein.”

The 34-year-old Mr. Hilfiger is not shy about sharing his vision of his future. For three months a Times Square billboard compared him to those designers, with Perry Ellis thrown in for good measure. Now a 10-second television commercial and a six-page magazine ad announce: “First there was Geoffrey Beene, Bill Blass and Stanley Blacker. Then Calvin Klein, Perry Ellis and Ralph Lauren. Today, it’s Tommy.”

In an industry where reputations usually take root slowly, Mr. Hilfiger’s is being created from scratch in less than two years. Eighteen months ago he was a freelance designer with no formal training and a handful of clients. Today he is a project of Murjani International Ltd., a leading apparel manufacturer, which has spent up to $20 million, and plans to spend millions more, to make his name a household word.

The strategy is raising eyebrows—and a few voices—in the fashion industry.

“I give it a year,” said Jack Hyde, consulting head of the Menswear and Marketing Division at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “He’s not a designer, he’s a creation.”

But Mr. Hilfiger and his backers express confidence in their plan.

“I think they felt I was the natural all-American-looking, promotable type of person with the right charisma,” said Mr. Hilfiger, who bounces when he talks. “I’m that person. I’m a marketing vehicle.”

The company calls the look “The New American Classics”—oversized oxford shirts with large pockets, khaki pants with a signature button over the zipper, bright red blazers with contrasting lining. Shirts sell for $40 to $50, slacks from $45 to $55, jackets for $90 to $160. The first shipments, made largely in the Far East, arrived in the stores last spring.

Reaction to the collection has been mixed. “Calvin Klein did that four years ago, Polo did that last year, that was big in Europe four years ago, that’s long gone,” Mr. Hyde said as a model paraded before the Fashion Institute audience in a series of Tommy Hilfiger outfits.

Right now, it seems, Mr. Hilfiger’s advertisements are better known than Mr. Hilfiger’s clothes. The campaign was developed by George Lois, of the advertising firm of Lois, Pitts & Gershon, who arrived at a planning meeting carrying samples of ads for such designers as Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Perry Ellis, Alexander Julian, Robert Stock and Giorgio Armani.

“We bought every telephone booth in New York,” said Matthew Rubel, vice president of Tommy Hilfiger. “We bought the billboard in Times Square.”

The company expects sales of $16 million this year, about as much as it has spent to promote the line in the last 18 months. “It’s in its infancy,” Mr. Hilfiger said. Soon, Mr. Horowitz said, the Tommy Hilfiger name will be licensed on such items as dress shirts and accessories. In June, Mr. Hilfiger will introduce his women’s apparel line.

“We think we’ve found the formula,” Mr. Hilfiger said. “We found the way to tell the public we’re here without being too arrogant. We created a whole fame.”

DESIGNER DONNA KARAN:

HOW A FASHION STAR IS BORN

Donna Karan at an event at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1986.

For a designer of clothes on New York’s Seventh Avenue, the capital of this country’s women’s fashion industry and the center of a $20 billion business, a car and driver is a sure sign of success. Each weekday evening near 39th Street, in the vicinity of 550 Seventh Avenue, the most elite building in the garment district, the chauffeurs and limousines can be seen arriving in clusters.

A few months ago, the industry noted that someone new had joined this group. A driver named Marvin Morris began showing up in a beige Lincoln Town Car, waiting patiently each evening near 550 for his boss, Donna Karan, who is generally considered by the fashion press and retailers to be the newest industry star.

In just 12 months, Donna Karan, New York, has become the designer label that sells out in the stores faster than any other. The Karan clothes are a prime resource in 120 of the most prestigious stores in America, among them Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s, I. Magnin and Bergdorf Goodman. According to Bergdorf’s chairman, Ira Neimark, the Donna Karan boutique—the area of the sales floor in which her designs are sold—produces “the highest sales per square foot of any American designer space in the store.” Saks Fifth Avenue concurs—a particularly significant declaration because Saks has devoted more square feet to the Karan clothes that any other store and has the boutiques in 11 of its 41 branches. Marvin Traub, chairman of Bloomingdale’s, says, “Our first-year Karan sales figures are close to $2 million, and they would be even better if we had them in all our stores.”

Miss Karan takes on her own label at a time when the risks are high. A young designer named Stephen Sprouse, for example, was discovered in 1983, was hailed as the latest fashion superstar in 1984 and disappeared in mid-1985. His fall collection for that year, dubbed a success by the fashion press, was never manufactured, because his company owed at least $600,000 to creditors. “Fashion,” says Jay Meltzer, an apparel analyst for Goldman, Sachs & Company, “is a high-risk investment. If it works, it’s wonderful.” The fact that most women now work in offices has had an enormous effect on clothes and the money made from them, as anyone familiar with the histories of Calvin Klein, Anne Klein & Company and Liz Claiborne knows well. But Donna Karan’s clothes push the working woman idea further. They are made, the designer says, for the needs of top professional women—women in charge, women so sure of themselves and their careers that, even at work, they can enjoy clothes that are sophisticatedly curvy and, as opposed to those of, say, Anne Klein, a bit sexy. Not all the women who buy the clothes hold down an executive job, of course, or a job of any kind. But the interesting fact is that they seem to want to look as if they do.

Women first encountered the clothes that Donna Karan designed for her own label at a showing at the Bergdorf Goodman store in New York on June 18, 1985. Because fashion is a business in which a tiny change, a nuance of design, can have important consequences, Miss Karan’s designs were hailed as a totally new concept of dressing. Although that was an overstatement, the idea behind these clothes obviously filled a void. The outfits begin with a pair of semi-opaque, dark, waist-length tights. Next comes a garment called a bodysuit, a slip-on of Italian-made jersey or knit. It has long sleeves, pulls on over the head, fits snugly and fastens with snaps at the crotch. This serves to replace a conventional sweater or blouse. Donna Karan has designed more than a dozen versions, most with pads to shape the shoulders. Over all this the designer wraps, or ties, skirts, shawls, jackets and coats, most made of fabric from the superb mills of northern Italy and all draped and shaped with luxurious folds.

These clothes retail from $180 for some of the bodysuits to as high as $2,200 for one of this fall’s new baby llama coats. Most of the outfits can be assembled for about $1,000, and another $1,000 or so is needed to accessorize them the way Miss Karan intends.

The fashion press was impressed by the clothes last year. The designs were featured many times in Women’s Wear Daily and shown twice on the covers of Vogue and the Fairchild Publications’ fashion newspaper, W. There has been extensive coverage in Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Times Magazine, Elle and in leading British and French fashion magazines.

The clothes she creates, Donna Karan says, are made to enhance her own figure. She is constantly concerned about her trim, but not rail-thin, body. Every day she spends 12 minutes on an exercise bike, and three mornings a week she works out for an hour under the eye of a personal trainer. “I must, I must, I must improve my bust,” she chants at one point. Reflecting this concern, her designs have a way of emphasizing the curve of the waist and the hips without stringently outlining them. The shawls and jackets are camouflage for bumps or protrusions.

BRACES: HIDDEN ASSETS GO PUBLIC

It’s hot and muggy, and all around town a sartorial secret of some of New York’s most conservative men is being revealed as they doff their jackets on steamy streets.

Suspenders—or braces—in wild stripes, polka dots and plaids are emerging from beneath conservative business suits. Nude women and acrobats and devils and dollar signs stream down starched shirts. Why? Well, basically to hold up their trousers. But that is far from their only appeal.

Many men say they wear flashy braces as a counterpoint to their serious business lives.

Call them braces or suspenders—the words are used interchangeably, though with a strong preference for the former among the affluent and assured. Either way, they are now big business, high style and an easy last-minute gift for Father’s Day.

Nowadays, suspender stocks go far beyond the traditional solids, jacquards, brocades, foulards, florals and paisleys, stripes, spots and plaids. While some snappy dressers such as Philip B. Miller, chairman of Marshall Field’s in Chicago, still favor simple solid colors, today’s best-selling brace styles are motifs: roosters, parrots, devils, owls, Confederate flags, playing cards, bulls and bears dripping ticker tape, cupids and acrobats.

America’s most conservative men are the leaders of this resurgence. “Your more affluent people wear braces,” said Elliott Rabin, co-owner of Peter Elliott (1383 Third Avenue at 79th Street), a speciality shop.

“I wear naked ladies,” said Sewantana Kironde, a director of the Chase Investment Bank. He calls his collection of 20 braces “a sartorial pretension.”

That pretension is often passed down through generations. Jack Heller, the Foreston Development’s president, whose grandfather always wore braces, said: “They put humor into an otherwise serious life.”

OCTOBER 1, 1986

LIFE IN THE 30’S

An 80’s fashion staple: leggings and high-top sneakers.

Who are these people who can take a pair of black pants and a black sweater and an important jewel and turn it into a fashion statement anyway? I want to meet one. I don’t know these people. I know people like me who buy outfits—the kind of people who have a party to go to and panic, and in that panic run out and make a kamikaze attack on a dressing room and buy themselves an outfit. Three months later, they run into that outfit in the closet and say, like the caterpillar in Wonderland, “Whoooo are Yooooou?”

This is why I need a fashion arbiter. You’ve read about fashion arbiters in the newspapers, people in black pants and important jewels who come out twice a year and say something like “bolero jackets.” And there you are. Six months later you’re squeezing into a bolero jacket and wondering where all that thigh came from.

Luckily my fashion arbiter is not exactly like that. My fashion arbiter is my sister. She is young, hip and on a budget, so she always knows which young, hip and cheap things are coming along. She knows my strengths and weaknesses.

My strength is that I have credit cards and will do what she says. My weakness is that I am old. She can’t come in and say, “Things with big holes in them and a rosary around the neck,” because I just won’t listen. My other weakness is that I can easily get bogged down in fashion trends and embarrass her by slogging around in big shirts a full year after big shirts have become passe. (Of course, there was a time when I never did anything but slog around in big shirts or their dress equivalent. But my sister does not handle maternity trends.) Twice a year, my sister comes into my kitchen and says something like this:

“Reeboks. With heavy crew socks scrunched down.”

That was last year. Imagine my surprise to find out that the trend of the season was an antelope. How would I wear it? What would I wear with it? Where would I keep it? Would the dogs like it? And what about the crew socks? Were they for me, or the antelope?

“They’re sneakers,” my sister said. “Leather. White. Black. Pink. Preferably high tops with a velcro close.” “What do I wear them with?” I said. “Stirrup pants.” “Stirrup pants? What are stirrup pants?” “They’re like made of stretch fabric and they have stirrups that go under your foot and you wear them with scrunched down crew socks and the Reeboks.”

“Wait a minute,” I said. “These sound like stretch pants. I know what stretch pants are. People wore them in the 1960’s and everyone looked terrible in them except for Marilyn Monroe.”

“They are just like stretch pants except they look good,” my sister patiently explained. “Get a big sweater. Get Reeboks. Get scrunched down crew socks.”

So I have to stick with my sister no matter what. Not long ago she came into my kitchen and said, “Shells.”

I said nothing. My immediate impulse had been to ask about sand and mollusks and whether lobsters were included, but I was still stinging from the antelopes. “And hoop earrings,” she added. “You don’t mean shells as in blouses, do you?” I said. “No sleeves? Round neck? Ban lon?” “What is Ban lon?” my sister asked. “Never mind. Those shells?”

“Yes, those shells,” my sister said. “With a short straight skirt. Big hoop earrings. And flats.”

My whole life began to pass before my eyes. For a moment I thought longingly of taffeta and bustles as I realized that if I took this advice I was going to be wearing approximately the same outfit I had worn to a particularly dreadful junior high school sock hop when I was 13 years old.

“I did this 20 years ago,” I said. “But 20 years ago I had no thighs. Now I have children. I already did shells and short skirts and big hoop earrings.”

“Well,” said my fashion arbiter, “I think you’re going to do it again.”

AUGUST 2, 1987

On Campus, the Look Is, Well, Studied

The collegians of the 1980’s have in fact become cleaner cut and more clothes-conscious than those of the 70’s. Even those completing their schooling on campuses with a Bohemian flair say the number of students wearing baggy, earth-colored clothes has dwindled in the last few years and that more students are adopting a sportier, more conservative appearance.

“In the 1970’s, the idea of caring about your college wardrobe was outmoded,” observed Sandy Horvitz, fashion director at Mademoiselle magazine. “But this is the 80’s, and people seem more into clothing and being a little chic.”

Fashion experts have already forecast a number of campus-bound fads for fall—from kilt pins skewered through Oxford shoes instead of laces for an offbeat preppy look for women to oversize button-downs in prewrinkled cotton for a more-rumpled-than-thou look for men.

Students in or near an urban area seem more willing to experiment with styles and accessories. “Most people dress for effect—political, social or otherwise,” said Morris Panner, now a third-year student at Harvard Law School. “You see a lot of classic L.L. Bean dressing, as well as the latest styles out of New York.”

On the West Coast, trendiness reigns. In southern California, especially in the Los Angeles vicinity, dressing draws its inspiration from the surfer culture as well as from national currents. For the moment, several styles rage: oversized, wildly patterned and brightly hued shorts; huge T-shirts and sweaters; stone-washed denim jackets; pastel sweatpants and sweatshirts and “micro” mini-skirts in denim, suede and leather. In northern California, however, where the weather is more variable, campus clothes largely resemble those of the Northeast.

There is one kind of student that seems rather hardened to the vicissitudes of style—the graduate student. The lack of interest usually reflects these students’ concerns with more weighty matters, namely gearing up for the career track. Yet a certain self-assurance appears to take hold at that stage as well.

“You already have your own identity, and you know that image is not going to make or ruin your graduate-school career,” said Chris Reid, a first-year student at Georgetown Law School.

THE SWAGGER OF CHRISTIAN LACROIX

It is a hot August afternoon in the south of France. A gypsy woman stands in a shady doorway off the sunlit village street. She beckons to the woman, who approaches and gives her some coins. She reads his palm. Then Lacroix turns and, with a big smile, reports to his friends:

“She says I’ll be famous in six months.”

Everyone has a good laugh. Six months! What an out-of-date gypsy! The French news magazine Paris Match is on the stands this very August day with a big spread about Lacroix’s spectacular rise to the top of the fashion world. Newspaper stories, some with front-page headlines, have just appeared in France, Britain, Italy and the United States. Radio broadcasts and television spots from all over have been pouring out ardent enthusiasm for Lacroix’s first couture collection.

People who follow fashion are saying that no reputation has ever been made as quickly as Lacroix’s, no new direction set so suddenly. True, they say, Lacroix has come out of the Paris couture, that rarified old world of made-to-order clothes for superrich women, but they are certain his ideas will be copied everywhere. They contend his influence will be evident soon in the stores, no later than this winter, when millions of women will begin to dress his way: in clothes that are unabashedly glamorous and theatrical.

Last January, he left his job at the Paris couture house of Jean Patou, where for the past few years he had been designing dramatic couture clothes that created a stir. In 1986, in particular, he introduced bouffant (or “pouf,” or “bubble”) cocktail dresses that were so widely copied that they quickly changed—from slinky to effervescent—the way many fashionable women looked in the evening.

On July 26, Lacroix showed 60 luxurious outfits to the world’s fashion press and to key figures in the fashion industry. They were mostly dresses he had designed for women to wear to the fanciest social occasions—in his words, “a dress for one woman for one occasion.” All were made of sumptuous materials—satins, velvets, laces, embroidery and furs—and with shapes and details inspired by the traditional flouncy costumes of southwest France. He employed unusual geometric patterns and mixed such colors as orange, scarlet, fuchsia and purple. He decorated the clothes with thick embroidery, and with braid, beads and jewel-like trimmings. Necklines plunged in shawl-like vees, and the silhouettes were bouncy and curvy. The clothes matched in theatrical thrust the music Lacroix’s models strutted to—Andalusian themes full of trumpet calls and assertive flair. Nothing was sedate or retiring. Lacroix’s performance made the critics gasp.

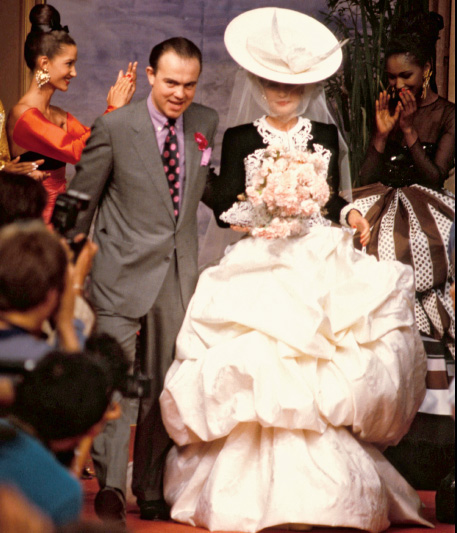

Designer Christian Lacroix showing his Haute-Couture, Fall-Winter collection in Paris, France, on July 26, 1987.

American stores went to battle to be the first to offer a garment bearing the Lacroix label. Bloomingdale’s won. On Wednesday, Sept. 16, as guests arrive at sunset for a party in the New York store, a single outfit from the Lacroix couture collection—No. 27, a brown, chartreuse and pink satin cocktail dress in size 6—will be unveiled in a Bloomingdale’s Lexington Avenue window. The dress will go on sale after 10 the next morning—for $15,000.

Asked where he wants to be in five years, Lacroix says, “I want to deserve all the success of this couture, to prove that Agache did not make a mistake. I think I have to be careful with success, to remain young. Perhaps the secret is enthusiasm. We have to stay passionate, to have joy and happiness with our work. We hope not to take ourselves too seriously. Well,” he makes a quick gesture with his hand and smiles, “perhaps just a little serious in business.”

Acid Wash Gives a Lift to 7th Avenue

The surprisingly simple technology of washing jeans in chlorine to reduce the stiffness and abrasiveness of the cotton denim has been a boon to the often-depressed garment industry. The chlorine removes dyes, giving the garments a lighter, worn appearance while softening them.

First used two years ago by the Italian company of Rifle Jeans, the process was dubbed acid wash, reflecting the streaked appearance of the finished product, as a sales tool. In fact, no acid is involved. “The term acid wash is a complete misnomer,” said Joyce Bustindy, a spokeswoman for Levi Strauss & Company. “We call our process white wash.”

The process was quickly picked up in the United States, according to New York garment makers, and has figured in the sale of millions of jeans, jackets and skirts.

“Acid-washed clothing is the most important thing that has come along in the men’s and women’s garment industry in years,” said Jack Taylor, divisional merchandise manager of Gottschalk’s Inc., a retail chain in Fresno, Calif. “We’re selling thousands of them a week in our 11 stores, in all price brackets. They’re extremely popular for the 14- to 26-year-old market.”

MAY 8, 1988

MEN’S STYLE; BULLS AND BEARS

Jay Spieler says he’s still partial to the vivid shirts, paisley ties and plaid suits he wore in the giddy days before Black Monday. Spieler, a broker with Drexel Burnham Lambert, insists last October’s market collapse hasn’t caused him to change his image by a thread. But others, still feeling last October’s aftershocks, are trading in their showy plumage for something more subdued.

Wall Street, to be sure, has traditionally been viewed as a bulwark of sartorial conservatism. And though its somber image has grown livelier in recent years, that trend has, to some extent, reversed itself. Does this mean the era of “imperious excess” described by Tom Wolfe in “The Bonfire of the Vanities” is on its way out?

Some people think so. “Seasoned and sophisticated men are dressing less ostentatiously,” says Robert Minicucci, a young investment banker at Shearson Lehman Hutton. “Corporate America is looking more for good ideas than for gladhanders who have their suits made in Savile Row.”

Similarly lofty sentiments echo along corporate corridors and issue from the lips of merchants who cater to a downtown trade. Some believe Wall Street’s renewed tendency to dress down predates Black Monday, and owes its revival to a mix of factors, not the least of which are last year’s insider trading scandals. “After the Boesky thing,” says Jay J. Cohen, an executive vice president of Taylor & Ives, a corporate design and financial advertising firm, “everyone wanted to keep a low profile.” To that end, he believes, some men have adopted a calculatedly nondescript style, donning muted sack suits and immaculate white shirts as a form of sartorial camouflage. The object, says Cohen, is to create a persona that “blends in with the crowd.”

More telling, perhaps, is Ralph Lauren’s decision to issue the sack suit. For fall, he is showing a natty, squarish model complete with soft shoulders, three buttons, a back vent and flat-front trousers.

But there are limits to all this sobriety. Heavy-soled brogues, plain shirts and muted patterns may, ironically, be riding the crest of fashion’s new wave. Yet spending hasn’t suffered visibly.

A seasoned Wall Street banker with sensitive fashion antennae interprets this news in more human terms. His friends, he says, are swapping their gold-banded watches for leather-strapped vintage models, exchanging their suspenders for crocodile belts and other old-money artifacts. “The look,” he notes, “is understated, but it still costs.”

JANUARY 24, 1988

THE SHOULDER PAD: LIKE IT OR LUMP IT

This will be remembered as the year of the shoulder pads. As fast as I could take them out, designers and manufacturers were putting them in.

Wearing what is in effect prosthetic devices says a lot about our society. Contact lenses are in, glasses are out. Our bodies have to appear perfect, slim, muscular. Shoulder pads must be surrogate muscles. On those of us foolish enough to leave them in, it can backfire. A bag slung over one’s shoulder can cause the pad to migrate onto the edge of the shoulder, giving away the fashion secret. Worse yet, washed ones can lump up and create an unusual silhouette.

But the thing that annoys me most is what they attempt to transform women into: men.

Joan collins wearing her iconic large shoulder pads!

A stylish suit with straight, quarterback shoulders and a slim, tubular skirt is entirely antithetical to the shape of a woman’s body.

I’d like to ban on shoulder pads for environmental reasons as well. Foam does not deteriorate as fast as fabric, leather or even vinyl, as anyone who has ever sat in a 10-year-old car seat knows. Years from now, archeologists will unearth hundreds of foam triangles attached to tattered shreds of linen and ask, “Why ruin this nice piece of fabric with a hunk of foam?

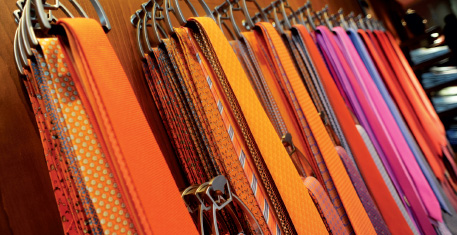

TO START WITH…; AN ARTFUL PLOY

Hermes ties.

Hermes silk neckties have survived the market crash as Wall Street status symbols, firmly knotted around the necks of investment bankers, bond traders and other highfliers.

Recently, a group of investment bankers was observed in the firm’s executive dining room, pondering the subject of the Hermes tie over broiled swordfish steaks and Diet Cokes.

The conversation suggested arbitrage as the bankers compared the prices they pay for the only item of sartorial splendor Tom Wolfe ignored in “The Bonfire of the Vanities.” The duty-free shop at the Tokyo airport used to have the best price and selection, one man said, but the strong Japanese yen has made shopping there all but prohibitive. The duty-free shop in the Paris airport is good in a pinch, volunteered another, but it doesn’t have the best patterns. A third banker spoke up: The Hermes boutique on 57th Street in Manhattan offers 50 patterns in a range of 12 colors. (There aren’t any regimental stripes, though. The French go to England for those.) Fifty-seventh is fine, commented still another banker, if you are inclined to pay $75 for a tie.

John Giroux, a senior partner in the law firm of Dumler & Giroux and a man who often wears Hermes ties, counsels, “Anyone you could conceivably want to impress would already know it’s Hermes.”

JANUARY 15, 1989

IT’S A SMALL WORLD

Angel Antonio Sanchez-Cabanas turns away from the glare of Madrid’s midday sun and leans his frame against a wall, the better to show off his garb. He wears a snug-fitting toreador-style jacket, a black ribbon tie—the sort of thing that Zorro might have fancied—and a Mexican belt with a hand-tooled silver buckle. He mates this all-Latin composite with American khaki trousers and a pair of fancy snakeskin cowboy boots, a present from a friend in Oklahoma.

At the Burghy, a popular fast-food restaurant in Milan’s Piazza San Babila, schoolgirls sip Cokes, preen and display their own variation of Euro-American chic. Here the requisite uniform is usually an oversized tweed sport coat pinched from papa, a demure white blouse with a Peter Pan collar and slim jeans that are faded to robin’s-egg blue. High-High-top sneakers, clunky Doc Martens shoes or slightly beat-up Top-Siders complete the look.

Prague has its own answer to the Burghy: the Moskva Arbat, a neon-lit, Eastern-bloc-style McDonald’s. Jan Zvonechek sits on a bench visitor, “America is very far away.” You wouldn’t know it from his outfit: he wears a black leather motorcyclist’s jacket, a pocket-size denim pouch hanging around his neck and a pair of loose, battered-looking jeans.

In metropolitan centers as far-flung and diverse as Shanghai, Bonn and Buenos Aires, there appears to be a consensus among the style-conscious young about what’s hip, hot or current on the street. These days it’s hard at a glance to distinguish a schoolgirl in Hong Kong from her leather or denim-clad counterpart in another part of the world.

It isn’t precisely that these kids look alike. But young iconclasts—who tend to spearhead trends—have forged a common fashion language whose vocabulary might include such oddly assorted elements as a fringed American cowboy jacket, German track shoes, a Soviet Army trench coat, a kilim-patterned vest, or dainty Edwardian knickers picked up at a London flea market.

The style derived from combining such items might best be described as a global melange. It is both the byproduct and the most visible expression of an international cultural synthesis trend watchers say has been long in the making. In the early 1970’s, Herman Kahn, the writer and futurologist, argued that with the spread of the Beatles’ influence, “pop” culture, which had previously been a strictly American phenomenon, became internationalized. “This sort of thing is going to continue,” Kahn predicted. “Perhaps in 1985, an Italian, Tanzanian, Bolivian or Turk will listen to an Icelandic pop singer on a Thai-made transistor radio, wearing clothes first designed in a boutique in Seoul.”

Kahn’s forecast for the 80’s wasn’t far off the mark. These days information travels with a speed even he might not have imagined. At a time when vanguard American rock groups play and record in the Soviet Union; when an architect working in Tokyo can instantaneously “fax” a series of drawings to his office in London, and when designs by fashion innovators like France’s Jean-Paul Gaultier or England’s Vivienne Westwood are splashed across the pages of magazines from Athens to Atlanta, it’s clear that young people draw their ideas from a common image bank.

“We find that young women everywhere have similar interests and preoccupations,” says Robert A. Gutwillig of Hachette, the publisher of Elle magazine.

For New Yorkers at fashion’s cutting edge, making fun of the norm is one way to stand out from the herd. At Patricia Field’s East Eighth Street boutique, which serves as an afternoon meeting house for many of the same young people who haunt Manhattan’s clubs late at night, a young woman with a starlet pout seems to consciously send up her own Long Island upbringing when she sweeps through the shop in a much-too-large mink coat. Field says a lot of her customers meld influences from sources as diverse as Harlem and St. Moritz for a similarly satiric effect. A typical look might consist of black stovepipe jeans, an acid green ski jacket and festoons of gold rope chains.

It may differ in its details, but what passes as street style varies little from place to place around the world, Field contends. She recalls a recent visit from a Soviet fashion editor, who, much to Field’s surprise, had never been to New York, but seemed to grasp intuitively what was hip by downtown standards. “The world,” Field says, “is a very small place.”

JULY 9, 1989

GUYS AND DOLLS AT THE MALLS

The prevailing wisdom has it that the mall is the great societal leveler of our time, where fashion is reduced to formula. Indeed, a casual observer of the youth scene in any one of the nation’s 32,000-plus shopping centers is tempted to agree with Joan Didion, who has called malls “toy garden cities … profound equalizers, the perfect fusion of the profit motive and the egalitarian ideal.” At Smith Haven Mall, a middle-income shopping center in Lake Grove, L.I., a group of 14-year-old girls, all coifed to resemble some hybrid of Rod Stewart and Farrah Fawcett, line up at the ladies’ room mirror and, with synchronized movements, mist their hair with fixative.

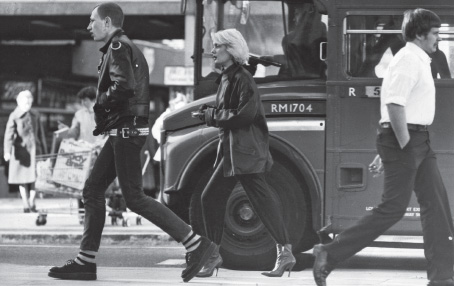

A young couple wearing leather jackets and 80’s clothing in London, 1980.

Mall kids tend to take their style cues from city kids. Indeed, at no time in memory have progressive—and often provocative—urban fashions been so speedily absorbed into the mainstream. These days, an onlooker might be hard pressed to tell a stylishly funky Manhattan East Villager from her equally stylish counterpart in Short Hills, N.J., or Plano, Tex.

One reason is that stores like the Limited, Benetton, Aeropostale, Units and Banana Republic—most of which once were exclusively urban, offering such style staples as pre-aged denims, canvas knapsacks, bandanna-print shorts, pocket T-shirts, tube skirts and leggings—now have outposts in malls across the country.

Mall girls, as a rule, cultivate a look of innocence, a buttoned-up but lightly teasing alternative to Madonna’s aggressively sexual lingerie chic. The newer style is espoused by pop performers like Debbie Gibson, who arrays herself in floral vests and flounced skirts over leggings, when she isn’t wearing tomboyish jeans cut off at the knees. Boys lean toward denim and leather, worn over T-shirts with loud skateboard-style graphics. The truly hip, though, pay homage to Rick Astley. The British rock star likes to wear double-breasted retro suits, patterned 1940’s ties and a modified pompadour reminiscent of the 1950’s.

Still, it wouldn’t be fair to accuse these kids of mechanically aping their idols. To use a word they tend to overwork, most aim for a look that has “quirk.” A trait that’s hard to isolate, quirk is expressed in the cartoonishly overscaled, but nonetheless elegant, tan linen suit worn by Shahal Khan of Bridgewater, N.J. Or in Amanda Gingery’s purple hose and close-clipped platinum hair, both of which contrast smartly with her thigh-high black knit dress. “I wear black a lot,” says the worldly 14-year-old from New Jersey. “It brings more attention to my face.” Who does she strive to look like? “Oh, nobody special,” she replies, a little vaguely. Gingery, too, likes to “make up” her look as she goes.

If Fashion Is Changing, it Must Be Almost 1990

Working on the collections introduced in Europe last month and in New York last week, fashion designers had more to think about than just making pretty clothes that sell. For those who see themselves as pacesetters and who try to anticipate how women would like to look before women think of it themselves, there was another consideration: These were the first collections that would be sold and worn in the 1990’s.

The 1980’s were a fairly nondescript period, which helps explain why Christian Lacroix’s poufs and bubble skirts, brilliant colors and inventive designs captured the attention of the fashion world two years ago. His wildly exuberant designs and costume party look loosened the shackles of restraint from other designers, and fashion was off on a binge. The bubble burst, but the Lacroix legacy remains: he has made the world safe for short skirts.

Most designers in this country and abroad have stopped their skirt hems just above the knees.

But hemlines alone do not make lasting fashion news. The next major change will come out of the test tube, says Geoffrey Beene, one of this country’s most innovative designers.

He foresees new fabrics that bond together, are warm without weight or are cooler for summer.

He has been focusing on short skirts for the last five years on purely logical grounds. Short skirts are easier to get around in and weigh less than long ones, he points out. He has sought out the lightest fabrics available.

It is a look already adopted by fashionable young women in the streets of Milan and Paris, and it has been featured by other designers, including Jean-Paul Gaultier in Paris and Donna Karan and Carolyne Roehm in this country.

The disappearance of the skirt and the unencumbered design of clothes in general will influence the look of the early 1990’s, at least. They may pave the way for truly modern clothes that reflect the new roles of modern women.

NOVEMBER 12, 1989

THE MODELS AND THE GLAMOUR TRADE

The search for “the look,” the magic that will make lipsticks jump into pocketbooks and magazines walk off newsstands, is endless and truly global. Start with the lips. Lips are big right now. Today’s hot models—Cordulla, Christy, Michaela, Naomi—all have full, seductive lips. It used to be the eyes that did the selling, but now the fashion magazines send out big wet kisses to the unsuspecting passerby.

Then there is height: 5 feet 9 inches is the minimum at most agencies, and several leading models are 6 feet or more.

Finally, the hair: it’s got to be a bob. Ever since Linda Evangelista, a gamine figure on countless catwalks and magazine pages, cut her hair this year and her career zoomed, the cool have got cropped.

It could be just that fluky. For all the money involved, the modeling industry is remarkably fortuitous and chaotic. When you call a modeling agency in New York, you immediately sense the frenetic pace of the enterprise. The receptionists and bookers answer breathlessly. Nervous energy buzzes through the line.

For a recent photo session, Naomi Campbell, a lithe 19-year-old model, was running four hours late. While the photographer, editor, stylist, and makeup artist pondered an empty set in a rented studio, her booker at Elite kept insisting Ms. Campbell had been delayed at the hairdresser. When she finally showed up, her hair didn’t look done.

Model Naomi Campbell

The British-born Ms. Campbell looks deceptively ordinary off camera but comes alive when the flash begins to pop, conveying a manic Josephine Baker-style energy. She has recently hit the big time—covers for Vogue, fashion shows for all the top designers and much-publicized nights on the town with Iron Mike. That kind of success is extremely rare and far from the workaday reality of the modeling business.

There are around 3,000 working models in New York—from cover girls to showroom and runway mannequins to production fit girls—toting portfolios, heading for go-sees, dashing from fashion show to fashion show. There are perhaps another million wanna-bes.

For several seasons, the designer shows have been dominated by an elite group of models, an A-team of tall, stately walkers, among them Iman, Dalma, Ilonka (many models are known professionally by first names, perhaps to enhance their mystique but also to protect their privacy), Anna Bayle, Ally Dunne, Magaret Donahoe, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Melanie Landestoy, Maureen Gallagher, Vanessa Duve, Louise Vyent and Veronica Webb.

This group, and a few others, are booked way in advance by the leading designers, and they appear in show after show, like some barnstorming basketball team. Samples are cut to fit their bodies. Cars are provided to shuttle them between assignments. Designers want to be certain their collections are shown in the best possible light—store buyers, being human, are not immune to glamour—even if it means paying $2,000 a day, including time for fittings, hair and makeup, for each model.

NOVEMBER 9, 1980

A NEW WHITE HOUSE STYLE IS ON THE WAY

American President Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) and First Lady Nancy Reagan relax in the sitting area of their White House bedroom, Washington, DC, November 1981.

Whether they’re in or out, intimates or sideliners, thrilled or able to contain their joy, the men and women around First Lady-elect Nancy Reagan agree on one thing: The White House is in for a change of style.

There will be, they say, considerably more social activity encompassing more people of diverse interests and occupations, imaginative and elegant parties, small dinners, and what several described as “a return of dignity.”

“Nancy has her own imprint,” said Harriet Deutsch, a friend who lives in Beverly Hills, echoing numerous others. “She has flair and style, and she won’t be like any other First Lady,” said Bonita Wrather, wife of Jack Wrather, a Los Angeles entertainment executive who is on the Reagan transition team.

There was, too, a general belief that Mrs. Reagan would not be as active politically as her predecessor, and that although she would be likely to influence fashion, it would not be through any conscious attempt.

“Her dinner parties are lovely, formal but casual with great warmth,” said Jerome Zipkin of New York, the social moth who flutters between coasts and continents and was with the Reagans the night of the election. “And Ronnie always makes an amusing toast that is pertinent.”

The White House menus would be neither faddish nor hokey, Mr. Fine predicted. “She doesn’t like to cook, but she likes to eat, and she knows food,” said Monsieur Marc, the hairdresser Mrs. Reagan visits in New York. “This will not be a Coca-Cola and ketchup White House.”

Another friend, describing the Reagan “warmth and style,” used the President-elect as an illustration. She was one of the guests at the election night dinner party given for the Reagans and their intimate friends by Mr and Mrs. Jorgensen.

“When the results were obvious,” she said, “Ronnie turned to all of us and said, ‘You were all so good to me when I was unemployed, and I’m not going to change a bit now that I’ve got a job.’”

JANUARY 4, 1981

BEHIND THE BEST SELLERS;

‘PREPPY HANDBOOK’

Last spring, Jonathan Roberts was 25 years old, a graduate of the Cambridge School in Boston and Brown, a funny young man who wanted to write. “Usually, people tell you to write what you know,” he says. “For years, I thought—‘What do I know? I’m just a Preppy.’”

Four UCLA students model the latest in college “preppie” fashion in 1981.

Then he thought again and confided his idea for a book to three Preppy friends, all single, clever, mid-twentyish and residents of Manhattan: Lisa Birnbach of the Riverdale School and Brown, Carol McD. Wallace of Country Day and Princeton and Mason Wiley of The Episcopal School and Columbia University. They agreed to collaborate. Miss Birnbach took on the chores of editor, writer and manager of the budget. She paid everyone else out of a checkbook imprinted with her nickname, “Bunny,” and a stemmed martini glass.

What emerged in September from the Workman Publishing house was “The Official Preppy Handbook,” by its own definition, the “In book of the season.” It is about Mummy and Daddy, whose lives and family rooms are imprinted decorously with the repeated images of ducks, whose Saturdays in the fall are given to tailgate picnics before the old school game, whose children are nicknamed Muffy or Missy or Buffy, Skip or Chip or Kip.

By the time Muffy and Skip become Mummy and Daddy, they will have mastered these and the million other details involved in living the elite and proper life of Prep. Or they can buy this book. Anyone can. “You don’t have to be a registered Republican,” the preface says invitingly. “In a true democracy, everyone can be upper class and live in Connecticut. It’s only fair.”

That may or may not be true, but it is funny. On the other hand, its authors say the book itself, 224 pages of wry detail, is a true account of being Preppy. “Our feeling was that it is such an inherently amusing subject that we don’t have to make jokes about it,” says Mr. Roberts. “All we have to do is tell the truth.” Who cares? Anyone to whom it matters, or who wants a laugh.

Big Hopes for Pudding Pops

WHITE PLAINS, July 9–First, there was Jell-O, a gelatin dessert, and its sales were good. Then General Foods created Jell-O pudding. Now, if the giant food company has its way, there will be Jell-O Pudding Pops, frozen pudding on a stick.

Conceived four years ago, test-marketed since 1978, Pudding Pops promises to be one of the most successful products to emerge in recent years from the General Foods kitchens. The company refuses to say when it will be introduced nationwide. But General Foods, which has already sunk millions of dollars into the new product, clearly has great hopes for Pudding Pops.

It’s hardly the Manhatten Project

“It’s potentially a very large business,” said Peter Rosow, general manager of the company’s desserts division, who predicts that it will make major inroads on the lucrative ice cream market.

Pudding Pops is only one new product at General Foods, which introduces several each year. Currently, it is also testing Jell-O Slice Creme, a freezer cake mix, and Jell-O Gelatin Pops, whipped gelatin on a stick.

While mothers still wanted its “wholesome goodness” for their children, Mr. Rosow said, afternoon snacks such as ice cream and packaged cakes were usurping the place of conventional desserts that were not readily portable and required preparation time. “The question was, ‘How can we put pudding in the path of the afternoon snack opportunity’?” said Mr. Rosow. “What we did was to freeze it and put it on a stick.”

Even its flavors were borrowed from traditional Jell-O pudding: chocolate, vanilla, banana and butterscotch. The reason, Mr. Rosow said, is that “its credentials are pudding credentials.”

General Foods scientists say that the development of Pudding Pops was not quite that simple, but the technology involved was certainly less sophisticated than that of other new General Foods products such as Lean Strips, a textured protein substitute for bacon, or frozen Crispy Cookin’ french fries. The dessert division does have some higher-technology products under development, but with Pudding Pops, Mr. Rosow conceded, “it is hardly the Manhattan Project.”

JANUARY 27, 1982

HOW THE ‘LIGHT’ FOODS ARE CONQUERING AMERICA

So many new “light” products have appeared on the market in recent months that light foods and beverages represent the major growth field in the American food industry. Such items as light canned fruit, light pancake mix, light spaghetti sauce, light salad dressing, light ketchup, light frozen dinners, light wine and light cocoa mix can be found on supermarket shelves. Other light fare that is to appear soon includes potato chips, snack foods, fruit drinks and cookies.

Industry executives and market analysts predict that the upsurge of light foods, which has been under way for two years, will continue and they venture that when the scramble to offer new products is over, low-calorie foods could constitute up to 10 percent of the $300 billion American food market.

“Light” (or the more trim spelling “lite”) is a loosely defined term to describe food and drink that contain less than the normal amount of something—sugar, starch, salt, alcohol—and, hence, fewer calories.

The Quaker Oats Company, which introduced its Aunt Jemima Lite Syrup in the summer of 1980, says it has increased syrup sales by 50 percent.

Del Monte reports sales of its light canned fruits—50 calories a half-cup serving against 85 for its regular products—“right on target.” Fernando R. Gumucio, head of the company’s grocery products division, said he believed that the fruits, which have less sugar in their packing syrup, would soon make up 15 to 20 percent of Del Monte’s sales of canned fruit.

Three nutrition and diet specialists who were interviewed said that light products might provide some help to people trying to reduce sugar or other elements in their diet but that the products were without much merit as weight-reduction aids.

“I don’t think all these products have really made a dent in the obesity problem in this country,” said Dr. Myron Winick, director of the Institute of Human Nutrition at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

A CUBE POPULAR IN ALL CIRCLES

The summer’s most popular cubes are not the colorless frozen water kind that do nothing but melt lazily in chilled glasses filled with tea, Perrier or Kir. No: This summer’s big cube is a maddening Mondrian-colored plastic puzzle, composed of 27 subcubes that rotate on horizontal and vertical axes. It’s called Rubik’s Cube, after Erno Rubik, a teacher of architecture and design at the School for Commercial Artists in Budapest.

The object of his addictive invention is to scramble the solid-color sides by twisting and turning the rows of cubes on their inner axes and eventually return them to their original places. New Yorkers are currently twisting and turning Rubik’s creation on streets, stoops, subways, buses, benches and beaches—and in bars, beds and, no doubt, hot tubs.

And the first regional competition for the title of United States Rubik’s Cube champion will be held Saturday in Burlington, Mass., near Boston.

According to Ideal, more than 10 million cubes have been sold worldwide since May 1980. Not all purchasers become as violent as the man who flung his cube from the window of a Fifth Avenue bus one scorching day last week, shouting “The hell with it. It’s impossible.” Actually, it’s not.

Benji Fisher, 18, a student at the Bronx High School of Science, says he can solve the puzzle in two and a half minutes. Mr. Fisher, one of eight United States representatives in the recent International Mathematical Olympiad, does not recommend haphazard twisting and turning. “If you make one move every second, you’ll probably get the cube back to the way it was in a few billion years,” he explains. Mr. Fisher, who says he did not use formal mathematics in reaching his solution, offers this advice: “Don’t be afraid to mess up something that looks good; find simple maneuvers that leave most of it unchanged; remember precisely what those moves do.”

B. Dalton Fifth Avenue began stocking the cube and gets $6.95, but prices vary all over town. It’s $9.95 at F.A.O. Schwarz, $10 at Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, $4.94 at the Toys “R” Us stores and $13 at the Museum of Modern Art, which recently accepted the cube for its Design Collection.

Children, according to the observations of Hilda Griesfeller of F.A.O. Schwarz, are the ideal “cubies.” “They have infinitely more patience,” she says.

Well, not all of them. When Dayvonne Anderson, 11, of Riverdale, found Ideal’s solution pamphlet to be as infuriating for her as the puzzle itself, she promptly tossed the cube in warm water, removed all 54 of the colored plastic coverings and rearranged them so that all six sides of the cube were once again a solid color. Then, with a sigh of satisfaction, she proudly announced, “I won!”

MARCH 14, 1982

Mainstream U.S. Evangelicals Surge In Protestant Influence

Often overshadowed by fundamentalism and shunned by church liberals, the mainstream of evangelical Christians has emerged as the most powerful new force in American Protestantism.

These evangelicals, mostly moderate in theology and politics, have been growing in numbers for years. But now they are strengthening their own institutions and making deep inroads in the 50-year-old liberal leadership of the major Protestant denominations.

Rev. Jerry Falwell with then-Vice President George H.W. Bush.

The signs of evangelical vitality are seen in the robustness of student movements, in the enthusiasm of lay people and in the clergy, which is well-equipped by education and outlook to bring the historic tenets of the Protestant faith to bear on 20th-century problems.

In essence, evangelicals stand between liberals and fundamentalists. They stress a personal commitment to Jesus, confidence in the Bible and enthusiasm for spreading the word and seeking converts. Evangelicals tend to hold in high importance the Second Coming of Christ, the saving act of Christ’s death, the Virgin Birth and the physical Resurrection.