When record numbers of Americans tuned into watch the final episode of “MASH” in 1983, the cozy, communal ritual of family viewing was already in the throes of a revolution. The old world of three major networks and high-minded scripted dramas was in its final days, as the spread of cable television fractured the viewing audience into thousands of constituencies, each with its own set of preferences and, thanks to the remote control, the power to dictate terms.

The original ‘Walkman,’ model TCS 300, made by Sony of Japan in 1980.

In all the arts, choice proliferated and habits of consumption changed. Sometimes new technology altered the landscape. The Sony Walkman allowed music fans to listen on the move. The compact disc, which instantly made the vinyl LP obsolete, improved sound quality and made storage easier. With the camcorder, introduced by Sony in 1982, anyone could make a video.

Television viewers faced a new world of seemingly infinite variety. The same small screen accommodated “Masterpiece Theater” and programs like “Married … With Children,” a raunchy new comedy on the fledgling Fox Network that pushed the boundaries of good taste.

MTV VJ Downtown Julie Brown on the set in MTV’s New York Studio in 1988.

MTV, a startup channel that broadcast music videos round the clock, turned out to be something more than a modern version of “American Bandstand.” It was a showcase for the latest street fashions, a training ground for aspiring directors, and a cinematographic innovator. Its hectic visual style, with constant quick cuts, had an immediate impact on longer-form television shows and film.

Culture became a battleground, reflecting the same divisions that would split the country evenly between red and blue states. Rock music loomed a moral threat in a way it had not since the days of Elvis Presley. Alarmed at the salaciousness and profanity she heard in rock songs, Tipper Gore joined forces with several other prominent political wives to form the Parents Music Resource Center. The organization lobbied the music industry to attach warning labels to records with sexually explicit or profane lyrics. The issue became more heated with the growing popularity of rap music, especially gangsta rap and groups like Public Enemy.

Projection of a Robert Mapplethorpe self-portrait during a protest at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1989.

The motion picture industry faced similar concerns. In 1984 it introduced a new rating, PG, to alert parents that a film contained language or images that might not be suitable for younger viewers.

The visual arts, not normally a hotbed of social controversy, inflamed passions, especially on Capitol Hill, when a new breed of political artists began showing at publicly supported museums. Robert Mapplethorpe’s elegant, shockingly sexual photographs of gay men caused a furor when they were included in an exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington that was funded, in part, by the National Endowment for the Arts. Andres Serrano’s photograph “Piss Christ,” which shows a crucifix immersed in a glass vessel filled with urine, set off a storm of controversy and set the stage for the “culture war” between the art world, the endowment, and conservative lawmakers in Washington.

Strife and contention, although fierce, was intermittent. For most audiences the arts delivered pleasure, pure and simple. Hollywood film in particular fell into an easy rhythm of action movies, horror films and many, many sequels.

The 70’s had been a golden age of sorts, with challenging films both domestic and foreign. Martin Scorsese continued to flourish in the 1980’s, making what many critics called his finest film, “Raging Bull,” but the big box-office hits tended to be franchise films like “Beverly Hills Cop,” “Lethal Weapon,” “Airplane” and “Halloween,” which generated sequel after sequel. The “Star Wars” juggernaut continued to roll in “The Empire Strikes Back” and “Return of the Jedi,” both phenomenally successful, but still not as big as Steven Spielberg’s “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.”

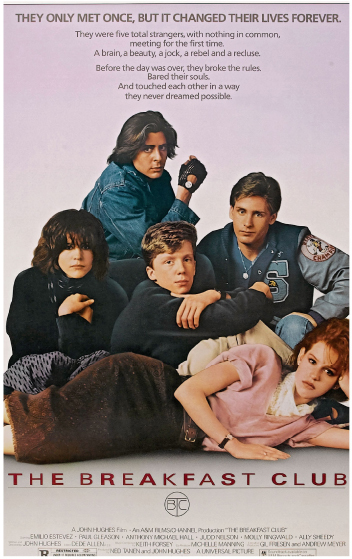

The target audience was, increasingly, young. John Hughes’s gentle comedies about teen life, like “The Breakfast Club” and “Pretty in Pink,” made instant stars out of Molly Ringwald and the young actors dubbed the “Brat Pack.” The growing sophistication of computer-generated special effects narrowed the differences between film and video games. “Tron,” a 1982 science-fiction film inspired by video games, marked a cinematic turning point. Actors faced a new dawn in which they ran a distant second to digitally produced images and explosions.

The big-budget blockbusters still left room for quirky independent films, which gained box-office credibility after the low-budget “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” took in millions at the box office. Directors like Jonathan Demme, in films like “Melvin and Howard” and “Something Wild,” and David Lynch, in “Blue Velvet,” showed that the renegade spirit of the previous decade had not died.

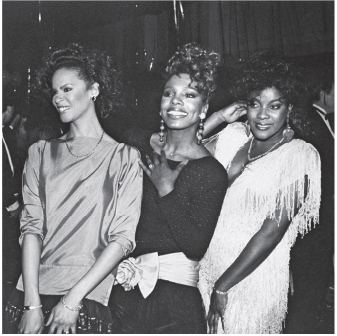

Actresses, Debra Burrell, Sheryl Lee Ralph & Loretta Devine from the cast of Dreamgirls.

In pop music, Michael Jackson emerged as a megastar. “Thriller,” released in 1982, became the best-selling album of all time. Madonna began her climb to international celebrity. In a memorable demonstration of celebrity power, the biggest names in rock ’n’ roll staged an epic benefit concert, Live Aid, to raise money to alleviate the famine in Ethiopia.

Jazz showed surprising resiliency. Miles Davis staged a comeback early in the decade, and a group of young traditionalists, led by a trumpet player from New Orleans, Wynton Marsalis, revived interest in the traditional jazz music of the 1930’s. Lincoln Center staged a series of concerts that led to the creation of a permanent jazz program.

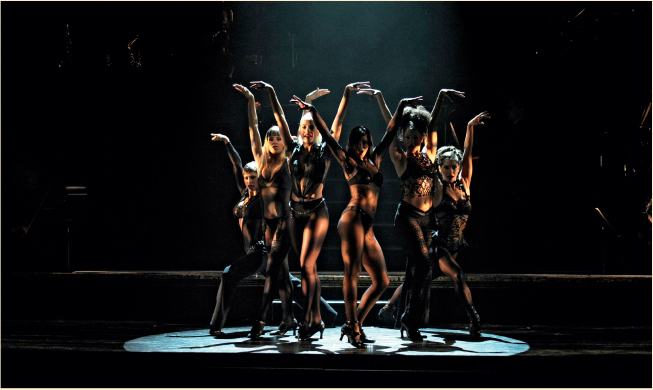

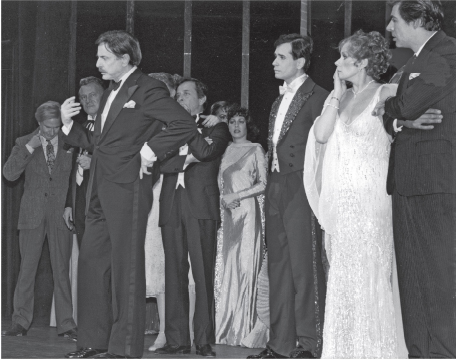

A British invasion swept over Broadway. One after another, lavish musicals like “Cats,” “Les Miserables” and “Phantom of the Opera” opened to rapturous applause and never left, running year after year. The homegrown Broadway musical, one of America’s great gifts to the world, seemed exhausted, although national honor was saved with the triumphant opening of “Dreamgirls.” The show, loosely based on the story of the Supremes, proved that Andrew Lloyd Webber did not have an absolute monopoly on the genre.

The Thatcher era, with its new mercantile spirit, provoked a response in politically minded playwrights like David Hare and Caryl Churchill, whose piercing looks at contemporary Britain impressed critics on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, Larry Kramer put the tragedy of AIDS on the stage with his groundbreaking play “The Normal Heart.”

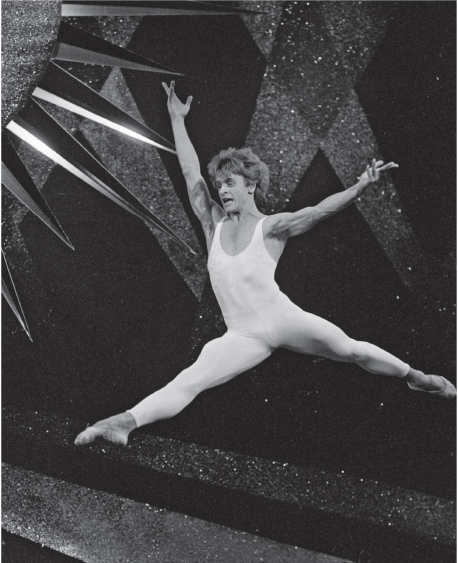

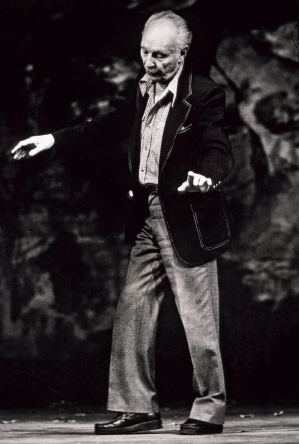

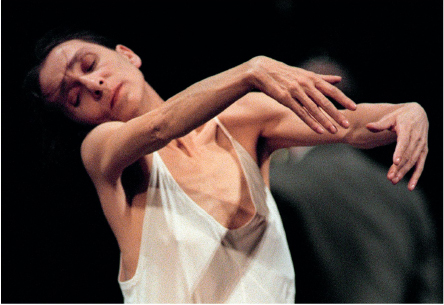

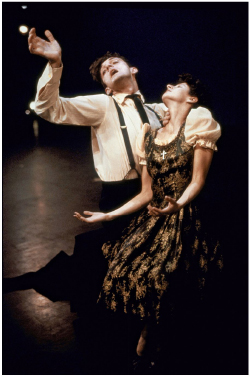

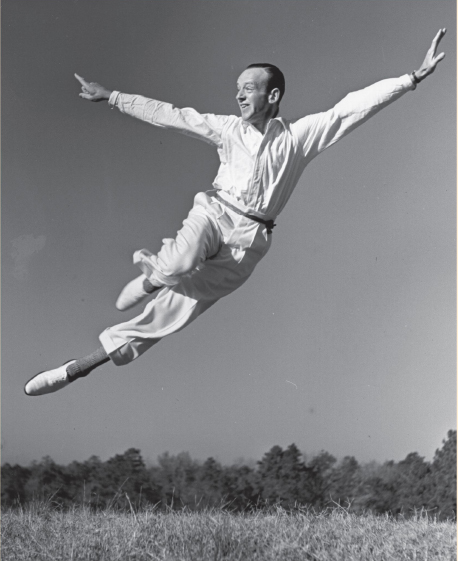

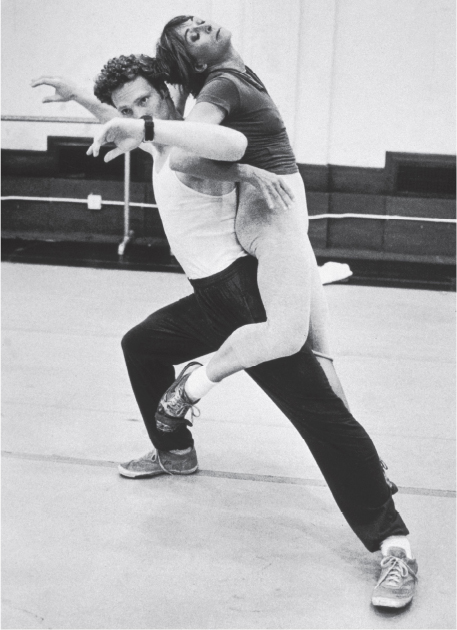

The dance world lost two giant figures, George Balanchine and Alvin Ailey. Suzanne Farrell, one of the century’s greatest dancers, retired. But there was also an influx of fresh talent. Mark Morris assembled a company of dancers that brought a new sense of wit and invention to the stage, and Twyla Tharp entered into a brilliant creative partnership with Mikhail Baryshnikov, who took over as artistic director of the American Ballet Theatre at the beginning of the decade. Darci Kistler, a protégé of Balanchine, became a principal dancer at the New York City Ballet, the youngest in its history at only 17.

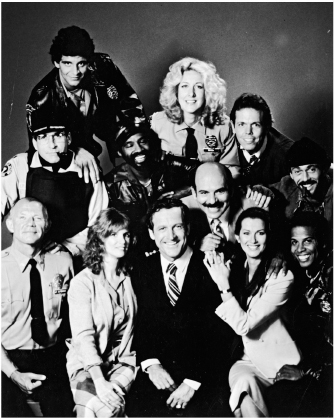

Cable television diminished the power of the networks, and the advent of CNN, not to mention the retirement of Walter Cronkite as anchor of “The CBS Evening News,” foretold the end of network dominance in the news. But the networks could still produce enormously popular comedies and dramas. Prime-time soaps like “Dallas” and “Dynasty” kept Americans glued to the set, and innovative series like “Cheers” and “Hill Street Blues” stretched the boundaries of their genres. “The Cosby Show” in particular was a landmark, a comedy series that presented black Americans in the round, endowed with the full range of human complexities, problems and emotions.

The visual arts took center stage, and not just because of the culture wars. A brash new style of painting, Neo-Expressionism, brought a new generation of artists to public attention. A flood of Wall Street money fueled sky-high prices for all forms of art, but artists like Julian Schnabel and Jeff Koons showed a distinct flair for marketing and media manipulation, proof that the lesson of Andy Warhol had been closely studied. Artists and their dealers no longer labored quietly; artists wanted to be famous, and their handlers took pains to make that happen. Never had the machinery of art, fashion, money and celebrity meshed so tightly.

The 1981 cast of “Hill Street Blues.”

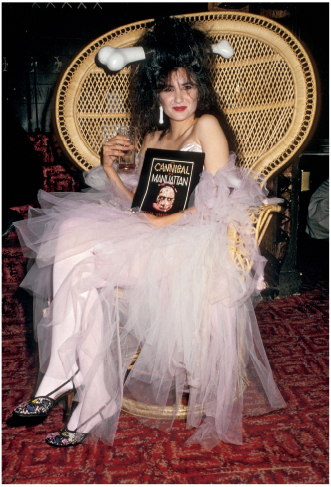

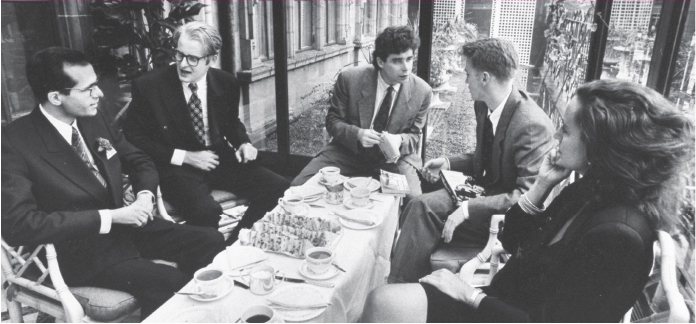

The Nobel Prize in Literature, often awarded to esoteric writers in past decades, redeemed itself in the 1980’s, honoring the likes of Joseph Brodsky, Czeslaw Milosz, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Wole Soyinka. At the same time, younger writers staked their claim. In the United States, a literary brat pack—Jay McInerney, Tama Janowitz and Bret Easton Ellis—looked like the 1980’s answer to the Beats of the 1950’s.

Commentators worried about declining literacy and the degeneration of the English language. The spread of Valley Girl dialect did not help. Allan Bloom, a classics professor at the University of Chicago, made the best-seller list with “The Closing of the American Mind,” a prolonged lament about the failure of higher education and the sorry state of American culture. E.D. Hirsch, another academic, put the case starkly in his best-selling “Cultural Literacy,” arguing that Americans simply did not know the facts that an educated person should know.

Both books set off a fierce debate. Were Americans under-educated, ill-informed, uncouth? If so, why did the 1980’s offer such rich pickings in art, music, theater, literature and dance? The decade was turbulent and confusing. The cultural friction was undeniable, so were the achievements.

Tama Janowitz at her book party for “A Cannibal In Manhattan” in 1987.

MAY 18, 1980

A Show That Might Even Have Dazzled Picasso; Picasso at the Modern

MOMA painting and sculpture director William S. Rubin in front of Pablo Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” in 1984.

“I want people to go out of here reeling, to have a sense of ‘How could he do it?” says William Rubin, who assembled the cornucopian Picasso show—one of the largest and most important art displays of our time that will cram the Museum of Modern Art’s entire building from May 22 through Sept. 16.

The exhibition, a near-$2-million extravaganza formally entitled “Picasso: A Retrospective” presenting almost 1,000 works in every medium by the protean Spanish artist, who is generally acknowledged as the dominant figure of 20th century art, will undoubtedly be Mr. Rubin’s curatorial chef d’oeuvre. About 300 of the works have never been seen before in this country, and 30 works have never been seen anywhere, including a 1956 wood version of a sculpture group called “The Bathers,” lent by one of Picasso’s heirs.

On the eve of the 100th anniversary of his birth in 1881, Picasso is seen, in the main body of critical opinion, as the towering progenitor of the art of our time, a position achieved not only by the immense fertility of his invention that led to the revolutionary style of Cubism, but also the sheer prodigality of his output. In the artist’s estate at his death, for example, were 1,855 paintings, 1,228 sculptures, 7,089 drawings, 3,222 ceramic works, 17,411 prints, and 11 tapestries. “No artist invented so much in one lifetime,” says Mr. Rubin. “There’s enough material in the MOMA show to make 50 other careers.”

The show was proposed by Mr. Rubin on a visit to Picasso shortly before the artist’s death in 1973. Picasso was “amused” by the notion of a museum-wide show, according to Mr. Rubin, and agreed to collaborate. But the artist’s death a few months later brought preparations to a halt. Only after the recent resolution of his tangled estate could the project again be seen as a possibility.

The show is certainly the most comprehensive Picasso exhibition ever mounted. “But the unbelievable thing is that you could fill the museum again with terrific Picassos that are not in the show,” notes Mr. Rubin.

SEPTEMBER 28, 1980

BUILDING ON EMOTIONS

There are many terms for it—romanticism, neo-eclecticism, a return to ornament, postmodernism. They do not mean the same thing, but they are all attempts to explain, in one way or another, a certain feeling that has been in the air for some time now. Architects and decorators talk willingly today of pleasure, of delight, of prettiness even. They seem to talk less of rules and more of whims, less of order and more of randomness, less of physical structure and more of spirit and mood. Even the most rigorous modernist seems compelled to say a word or two about emotional content when defending his or her work, and he or she who speaks only in terms of purity of space and structure, the words of modernism’s gospel, is likely to sound rather old-fashioned.

It is tempting, when one ponders the situation, to say that the world of architecture and design has been turned upside down. After all, two years ago Philip Johnson, once modernism’s leader, and John Burgee designed a limestone-fronted structure, complete with classical moldings, for the apartment house at 1001 Fifth Avenue in New York City. When one looks at this curious building and then looks back at, say, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s great 860-880 Lake Shore Drive apartments in Chicago of 1950, it is a startling comparison: The new building is what looks old-fashioned, while the “modern” building, the box of steel and glass, turns out to be 30 years old.

No more. Now, not only is Philip Johnson going about creating classical ornament, but we also have architects like Allan Greenberg, who is designing a “real” Georgian manse; Charles Moore, who has been mixing elements from various cultures and periods for some time and now does so with more exuberance than ever; Robert Stern, whose mix of classical allusions and elements from the Shingle Style is increasingly articulate; Michael Graves, whose rich colors and subtle forms, derived from classicism but highly personal, are nothing if not romantic. There are many other, younger architects working in similar directions.

This sort of romanticism is what we might call the romanticism of aspiration—it uses historical details and historical style in the hope of conveying certain qualities of a past period. It is a kind of design with a social goal as much as a purely visual one, and it often has a pleasing kind of innocence to it.

All of this is, at bottom, a reaction against modernism. Its austerity, we have finally realized, served too narrow a range of the human psyche; without a certain kind of attention to the broader range of human emotions, service to the eye has insufficient meaning.

This does not mean that modern design is finished, that we will see no more of it—far from it. But what we will see are more and more variations on modernist themes, such as a designer like Saladino offers or, as, say, Kevin Roche created in his sparkling, decorative, yet utterly modernist United Nations Plaza Hotel, an attempt to bring a level of emotional content to the modern design vocabulary.

JULY 12, 1981

EXPRESSIONISM RETURNS TO PAINTING

In art, every authentic style comprehends a distinctive point of view. It exalts certain emotions, and upholds certain attitudes. It makes a judgment about the medium, and a judgment about life. Upon its emergence it proffers a revision of existing ideas about art, and thus—either by implication or by direct assault—represents a challenge to the prevailing orthodoxies. Every genuine change of style may therefore be seen as a barometer of changes greater than itself. It signals a shift in the life of the culture—in the whole complex of ideas, emotions and dispositions that at any given moment governs our outlook on art and experience.

In the visual arts, a change of this sort is now apparently upon us in the form of an energetic wave of Neo-Expressionist painting. This burgeoning movement has swiftly achieved a remarkable success on both sides of the Atlantic—for it is as much a European as it is an American movement—and it is now the focus of a good deal of critical discussion and acclaim.

In this country, for example, the outstanding figures at the moment are Julian Schnabel, Susan Rothenberg and the British-born painter Malcolm Morley—three very individual artists whose work does not seem to have much in common until placed in the perspective of the conventions they have vigorously repudiated.

In Italy, where the movement has erupted with particular force, its leaders appear to be Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia and Enzo Cucchi—though they are themselves part of a larger group whose work has already been shown at museums in Basel, Essen and Amsterdam. In Germany, not surprisingly, the Neo-Expressionists have won a great deal of attention, for it was in Germany that the Expressionist movement originated some 75 years ago, and its revival is therefore seen as, among other things, a vindication of a national artistic tradition.

But what, as they say, is it all about?

One thing it is about, surely, is the legitimization of a mode of painting that exults in the physical properties of the medium, and in its capacity to generate images and stir the emotions. This is painting that makes a very frank appeal to the senses at the same time that it addresses itself without embarrassment to our appetite for poetry, fantasy and mystery. It swamps the eye with surfaces that are shameless in their exploitation of tactile effects, and with vivid images that are not always susceptible to easy explanation or understanding. It is painting that relies more on instinct and imagination than on careful design and the powers of ratiocination. It shuns the immaculate and the austere in favor of energy, physicality and surfeit.

Against the “closed” styles so long in fashion, the Neo-Expressionists offer us painting that is nothing if not “open”—painting that releases the medium from the restraints of high-minded theory in order to allow fantasy and emotion to play a more forthright role in determining the boundaries of pictorial discourse.

MAY 15, 1983

ARTISTS GRAPPLE WITH NEW REALITIES

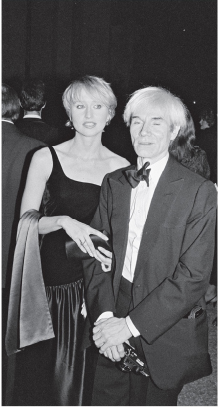

Cindy Sherman with Andy Warhol in 1982.

There is no question in most artists’ minds that the art world has changed dramatically in the last few years. It is bigger, faster and more conspicuous than before. There are more artists, dealers, collectors, agents, promoters and people writing about art. There is more to be won and lost now, at an earlier age.

In short, the art world has become big-time. With the emergence of a $2 billion a year art market in New York alone and the institutionalization of the avant-garde, not only by museums, where work is often on the walls while the radical edge is still hot, but also by universities, where more and more avant-garde artists have been hired to teach more and more studio art programs, art has entered the mainstream of American life.

What these changes mean for art, however, how they affect the making of art and the artists, is a matter of ongoing discussion and sometimes urgent concern. As art has entered the mainstream of American life, the mainstream of American life, with its turbulent as well as its bracing currents, has edged deeper and deeper into the world of art. On the one hand, the art world has probably never generated so much excitement and interest and touched off so many dreams. The audience for art continues to increase. With the success of such artists as David Salle, Julian Schnabel, Robert Longo and Cindy Sherman, all around 30 years old, and Keith Haring and Jean Michel Basquiat, still in their early twenties, artists now begin their careers knowing they have a chance for fame and fortune at an age that was almost unthinkable even ten years ago.

On the other hand, there is a widespread belief that worldliness, big money, instant stardom and art are incompatible—and that if they do co-exist, the integrity and scope of the art must suffer. There is no doubt that as the stakes increase, the pressures, distractions and temptations with which artists in New York now live have become more and more intimidating. Furthermore, as the media wait impatiently for the next “hot” artist and more and more collectors’ limousines roll into SoHo to line up for work that has not yet been created, there is also an increasing danger of artists becoming themselves commodities. “There’s this using up,” said the 31-year old sculptor Timothy Woodman. “You’re discovered, you’re used up, you’re out.”

The questions being raised about the art world now could not be more consequential. Is it still possible, given the conditions which have generated so much interest and made so much possible, to create work with the integrity and purpose that have always given art its necessity? With the pressure to “make it,” the possibility of something like immediate gratification, and the distorting amount of attention successful artists may receive, can artists continue to reach for something beyond vanity and the moment?

For some artists, whatever the situation, the issue has been and always will be the strength and will of the individual. “I really believe the pressure comes from me and not the art world,” Mr. Salle said. “I don’t think anything today has changed the difficulty of making significant art and the steep odds against it.”

JANUARY 8, 1984

PHILIP JOHNSON DESIGNS FOR A PLURALISTIC AGE

Several years ago, as it started to rain at an architects’ picnic in Princeton, one of those present suggested that the group call Philip Johnson and “ask him to have it stop raining.”

No one made the call, but the anecdote is telling. “He is the most powerful architect since Bernini,” says the New York architect Peter Eisenman. To many observers, Mr. Johnson is a figure of enormous power—an architect whose reputation is an issue almost independent of his buildings, and possibly one of his most impressive constructions.

But the appreciation is not entirely unmixed. The outspoken James Marston Fitch, professor emeritus at the Columbia University School of Architecture, says “he is impregnable,” even though “fundamentally frivolous.”

Mr. Johnson is perhaps now somewhere between being more controversial than ever and beyond controversy: the architect is attracting the most substantial commissions of his career—such as the proposal for four new towers he recently presented for the revitalization of Times Square. He is responding with designs, pleasing for some people, merely glib to others, but that are certainly expanding the traditionally conservative corporate palette.

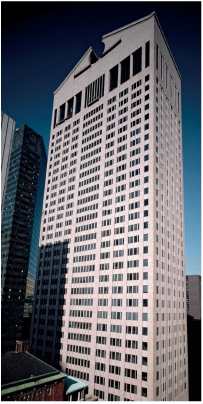

One of the few elements that ties Mr. Johnson’s widely divergent buildings together is, in fact, their pinstriped urbanity—their elegant finish helps mask the architectural shock that few other architects would be able to get away with. Besides the Chippendale top of the A. T.& T. Building, he has designed a Gothic skyscraper for Pittsburg Plate Glass, a Dutch-gabled high-rise in Texas, and is now working on a high-rise Welsh castle apartment building with a crenellated top for Donald Trump. Other than their sophisticated level of finish and detailing, a certain light Cole Porter wit, and their efficient interior planning, there are remarkably few characteristics common to these buildings—and none that might add up to a consistent system of belief.

As an architect who “cannot not know history,” Mr. Johnson has thoughts about his place in it, and as usual he is of several minds. On the one hand, he says, “we think we’re creating architectural history.” But on the other hand, “I don’t see myself as important, but I might eventually be considered important. With these startling commissions in different cities—like the Pennzoil—I’m getting a different level of acceptance than I used to.”

The A. T. & T. Building in New York City, designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee.

MARCH 7, 1986

GEORGIA O’ KEEFFE DEAD AT 98;

SHAPER OF MODERN ART IN U.S.

Georgia O’Keeffe adjusting a canvas from her “Pelvis Series-Red With Yellow,” in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1960.

Georgia O’Keeffe, the undisputed doyenne of American painting and a leader, with her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, of a crucial phase in the development and dissemination of American modernism, died yesterday at St. Vincent Hospital in Santa Fe, N.M. She was 98 years old, and had lived in Santa Fe since 1984, when she moved from her longtime home and studio in Abiquiu, N.M.

As an artist, as a reclusive but overwhelming personality and as a woman in what was for a long time a man’s world, Georgia O’Keeffe was a key figure in the American 20th century. As much as anyone since Mary Cassatt, she raised the awareness of the American public to the fact that a woman could be the equal of any man in her chosen field.

Miss O’Keeffe burst upon the art world in 1916, under auspices most likely to attract attention at the time: in a one-woman show of her paintings at the famous “291” gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, the world-renowned pioneer in photography and sponsor of newly emerging modern art.

From then on, Miss O’Keeffe was in the spotlight, shifting from one audacious way of presenting a subject to another, and usually succeeding with each new experiment. Her colors dazzled, her erotic implications provoked and stimulated, her subjects astonished and amused.

The artist painted as she pleased, and sold virtually as often as she liked, for very good prices. She joined the elite, avant-garde, inner circle of modern American artists around Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924.

Long after Stieglitz had died, in 1946, after Miss O’Keeffe forsook New York for the mountains and deserts of New Mexico, she was discovered all over again and proclaimed a pioneering artist of great individuality, power and historic significance.

Miss O’Keeffe had never stopped painting, never stopped winning critical acclaim, never stopped being written about as an interesting “character.” But her paintings were so diverse, so uniquely her own and so unrelated to trends or schools that they had not attracted much close attention from New York critics.

Then, in 1970, when she was 83 years old, a retrospective exhibition of her work was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The New York critics and collectors and a new generation of students, artists and aficionados made an astonishing discovery. The artist who had been joyously painting as she pleased had been a step ahead of everyone, all the time.

THE LOWER EAST SIDE’S NEW ARTISTS

In the early 1980’s, Meyer Vaisman and Peter Nagy were young artists in Manhattan, both in their early 20’s and both recently graduated from art school. And both, when unable to find an existing commercial gallery in New York to show their work, took an increasingly common step for young artists in Manhattan: they started their own galleries.

Today, Mr. Vaisman’s gallery, International With Monument, and Mr. Nagy’s, Nature Morte, are two of the most successful on the Lower East Side, a thriving new commercial art district in New York. And the two young men have become quite successful as artists, as well.

Their story typifies a change that has taken place in New York’s contemporary art scene, which in recent years has been transformed from a relatively small and cloistered world to a thriving industry that makes stars of unknowns and has spawned growing numbers of galleries, trade publications and entrepreneurs.

There were around 200 art galleries in the New York metropolitan area in 1976, mostly in the traditional art districts of 57th Street and SoHo, according to the Gallery Guide, which lists New York art galleries. Today, the guide lists 560 galleries in the New York area, including such Manhattan neighborhoods as the Upper East Side, NoHo, Tribeca and the Lower East Side. The Art Dealers Association of America estimates that there are $1 billion a year in fine-art transactions in New York City.

The breeding ground for many of the new artists has been the Lower East Side, which, in the last five years, has been the fastest growing of all the art districts of New York. Although there were virtually no art galleries there in 1980, there are nearly 100 there today. In tiny storefronts previously occupied by Ukrainian- and Polish-American shops, dozens of new art galleries have been started each year by young entrepreneurs, many of them young artists.

Some days, the Lower East Side, which is called the East Village by many, looks like a cultural version of the garment district, with artists and art handlers carrying canvases still wet with paint from their apartment studios to nearby galleries to display. The local cafes, which have proliferated along with the galleries, are filled with artists and dealers, and gallery owners frequently take groups of collectors to artists’ studios to try to interest them in works that are still in progress.

It is in this environment that many young artists have recently made their start in the art world—and done so with a splash.

FEBRUARY 10, 1985

NEW ART, NEW MONEY

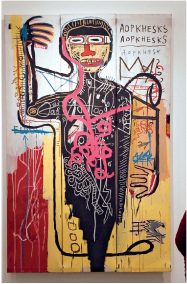

When Jean Michel Basquiat walks into Mr. Chow’s on East 57th Street in Manhattan, the waiters all greet him as a favorite regular. Before he became a big success, the owners, Michael and Tina Chow, bought his artwork and later commissioned him to paint their portraits. He goes to the restaurant a lot. One night, for example, he was having a quiet dinner near the bar with a small group of people. While Andy Warhol chatted with Nick Rhodes, the British rock star from Duran Duran, on one side of the table, Basquiat sat across from them, talking to the artist Keith Haring. Haring’s images of a crawling baby or a barking dog have become ubiquitous icons of graffiti art, a style that first grew out of the scribblings (most citizens call them defacement) on New York’s subway cars and walls. Over Mr. Chow’s plates of steaming black mushrooms and abalone, Basquiat drank a kir royale and swapped stories with Haring about their early days on the New York art scene. For both artists, the early days were a scant half dozen years ago.

Visitors stand among paintings by artist Jean Michel Basquiat which are part of an exhibition of 150 works of art by Basquiat, at Musee d’Art Moderne on October 15, 2010 in Paris, France.

That was when the contemporary art world began to heat up after a lull of nearly a decade, when a new market for painting began to make itself felt, when dealers refined their marketing strategies to take advantage of the audience’s interest and when much of the art itself began to reveal a change from the cool and cerebral to the volatile and passionate.

But today, contemporary art is evolving under the avid scrutiny of the public and an ever-increasing pool of collectors in the United States, Europe and Japan; and it is heavily publicized in the mass media. Barely disturbed by occasional dips in the economy, the art market has been booming steadily.

Take Basquiat. Five years ago, he didn’t have a place to live. He slept on the couch of one friend after another. He lacked money to buy art supplies. Now, at 24, he is making paintings that sell for $10,000 to $25,000. They are reproduced in art magazines and also as part of fashion layouts, or in photographs of chic private homes in House & Garden. They are in the collections of the publisher S. I. Newhouse, Richard Gere, Paul Simon and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

His color-drenched canvases are peopled with primitive figures wearing menacing masklike faces, painted against fields jammed with arrows, grids, crowns, skyscrapers, rockets and words. “There are about 30 words around you all the time, like ‘thread’ or ‘exit,’” he explains. He uses words “like brushstrokes,” he says. The pictures have earned him serious critical affirmation. In reviewing a group show of drawings last year, John Russell, chief art critic of The New York Times, noted that “Basquiat proceeds by disjunction—that is, by making marks that seem quite unrelated, but that turn out to get on very well together.’ His drawings and paintings are edgy and raw, yet they resonate with the knowledge of such modern masters as Dubuffet, Cy Twombly or even Jasper Johns. What is “remarkable,” wrote Vivien Raynor in The Times, “is the educated quality of Basquiat’s line and the stateliness of his compositions, both of which bespeak a formal training that, in fact, he never had.’

In the last year or so, Basquiat has established a friendship with an artist who probably understands the power of celebrity better than anyone else in the culture. Once when he was trying to sell his photocopied postcards on a SoHo streetcorner, he followed Andy Warhol and Henry Geldzahler into a restaurant. Warhol bought one of the cards for $1. Later, when Basquiat had graduated to painting sweatshirts, he went to Warhol’s Factory one day. “I just wanted to meet him, he was an art hero of mine,” he recalls. Warhol looked at his sweatshirts and gave him some money to buy more.

Their friendship seems symbiotic. As the elder statesman of the avant-garde, Warhol stamps the newcomer Basquiat with approval and has probably been able to give him excellent business advice. In social circles and through his magazine, Interview, he has given Basquiat a good deal of exposure. Though Warhol teases Basquiat about his girlfriends, Basquiat finds the time to go with Warhol to parties and openings. In return, Basquiat is Warhol’s link to the current scene in contemporary art, and he finds Basquiat’s youth invigorating. “Jean Michel has so much energy,” he says. One acquaintance suggests that the paternal concern Warhol shows for Basquiat—for example, he urges the younger artist to pursue healthful habits and exercise—is a way for Warhol to redeem something in himself. When asked how Warhol has influenced him, Basquiat says, “I wear clean pants all the time now.”

FEBRUARY 10, 1985

IN LONDON, A FINE HOME FOR A MAJOR COLLECTION

One of the more unpredictable places in which recent art of high quality can henceforth be seen in ideal conditions is on Boundary Road in Northwest London. As its name suggests, Boundary Road is somewhat on the edge of things. Lightly trafficked, it has a metropolitan bit, a suburban bit and a villagey bit. The villagey bit includes a betting shop, a take-out Tandoori shop, and in fact a whole clutch of the diminutive, highly characterized one-family stores that George Orwell described so well in the 1930’s. It also has, or had, a little factory tucked away at the back not far from the junction of Boundary Road and Abbey Road.

That factory was a rundown sort of place when it was bought a year or two ago by Charles Saatchi, who is best known as the co-founder in first youth of Saatchi & Saatchi, an advertising agency that does a multimillion-dollar business in many parts of the world. Charles Saatchi is also well known—some would say notorious—in the international contemporary art establishment for the collection of recent art that he and his wife have been forming since the late 1960’s.

The private collector of new art, as he existed in pre-revolutionary Moscow, in Switzerland in the first half of this century and in the United States today, has had few parallels in England. It was, therefore, thought in London to be in rather bad form—pushy, if not actually disreputable—when the Saatchis not only bought the paintings and sculptures that they most liked, but bought them in large numbers. No one knew exactly what they had, but in major international loan exhibitions they made their mark as lenders over and over again.

It did not endear them to English artists, who have a hard time scratching a living from local collectors, that they spent a lot of time in the United States and bought heavily in the domain of American art. Nor did it endear them to American artists that more recently they have bought heavily in the domain of German and Italian art.

This situation was further complicated by the fact that although in his professional activity Charles Saatchi is a laconic lord of language who can make one word do the work of 50, he has never in his life given an interview, whether about the collection or about anything else. Nor is he going to start doing so now. It is also pertinent that the four-volume catalogue is entitled “Art of Our Time” in very large letters, and subtitled “The Saatchi Collection” in very small ones. It includes appreciations of the artists by many good writers—among them Hilton Kramer, Peter Schjeldahl, Robert Rosenblum, Rudi Fuchs and Jean-Christophe Ammann—but the Saatchis themselves are never mentioned.

Given that the collection as catalogued includes nearly 500 works by 45 artists—of which perhaps one-tenth at most can be shown at any one time—the inaugural show could have been a promiscuous catchall. But the Saatchis have opted for plain grand statement, and for the presentation in depth of four artists—Donald Judd, Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly and Brice Marden. The result suggests that a golden age in art can take many forms, and that one of them can be found in the achievement of the 1960’s and 70’s.

Doubtless these matters will be debated as long as the Saatchis are an active force in the art market. Meanwhile, two things need to be said. One is that Max Gordon has contrived for them one of the most blissful spaces of its kind that this visitor has ever trodden. The other is that on the evidence of the catalogue there is material in the collection for a series of densely thought-through and sometimes definitive exhibitions that could continue for five or six years at least.

The unnamed gallery at 98a Boundary Road, London N.W.8. is at present open by appointment only. Anyone who is interested to go can telephone London O1-624-8299 as of now.

NOVEMBER 17, 1985

YOUTH—ART—HYPE:

A DIFFERENT BOHEMIA

Ann Magnuson sits on a worn couch in her East Village apartment, rummaging in the junkyard of American culture. She talks, with affectionate mockery, about icons and totems and slogans, past and present. Her allusions spill out like the contents of some crazed time capsule—Steve and Eydie, “The Beverly Hillbillies,” Patty Hearst, Gidget, Wonder bread, Amway, TV evangelists, Lawrence Welk, Jim Morrison and the Doors, Chicken McNuggets, high-fiber diets, midstate pork princesses, Mantovani, Mr. Spock and “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.”

Recently christened “the Funny Girl of the avant-garde” by People magazine, the 28-year-old conjures up these spirits in her satirical skits for downtown clubs such as Area, Danceteria and the Pyramid. Her characters include Mrs. Rambo, who shoots her way through Bloomingdale’s to save Nancy Reagan from getting a New Wave makeup job at the Yves St. Laurent counter, and Fallopia, Prince’s new protégé, who is really Delores Jean Humpshnoodleburger, a graduate of the Rose-Marie School of Baton and Tap in Duluth.

She is a performance artist with a cult following and the area where she lives and works is simply called downtown.

She is at the center of the vivid New York arts community that has captured international attention spinning what has come to be known as “the downtown style.” The artists cannibalize high art and the mass culture of the last three decades—television, suburbia, pornography, Saturday morning cartoons, comic books, Hollywood gossip magazines, spirituality, science fiction, horror movies, grocery lists and top-40 lists.

“It’s everything turned inside of itself, it’s sensory overload,” Ann Magnuson says. “It’s a postmodern conglomeration of all styles. You steal everything.”

Although there are one or two outposts above 14th Street, the community begins there and moves fitfully down Manhattan, through the East Village, the Lower East Side and, on the West Side, down through TriBeCa to the Battery. It tends to hug the edges of the island and carefully avoids that older artists’ haunt, Greenwich Village.

Just as irony is the hallmark of the downtown style, the word bohemia takes on an ironic twist when used to describe this arts community. For this is a bohemia, to use Ann Magnuson’s phrase, that is turned inside of itself, different from any that have preceded it. While past bohemians were rebels with contempt for the middle class and the mercantile culture, many of the current breed share the same values as the yuppies uptown.

This is a blue-chip bohemia where artists talk tax shelters more than politics, and where American Express Gold Cards are more emblematic than garrets. In this Day-Glo Disneyland, the esthetic embrace of poverty has given way to a bourgeois longing for fame and money. It is a world where nightclubs have art curators and public-relations directors are considered artists.

“Bohemia used to be a place to hide,” says John Russell, the chief art critic of The New York Times. “Now it’s a place to hustle.”

“It’s not chic to be a starving artist any more,” agreed Joe Dolce, a writer and publicist for the downtown nightclub Area. “It’s more chic to be making millions. Bohemia meets David Stockman.”

American actress, performance artist and nightclub performer Ann Magnuson.

NEW BREED OF HIGH-STAKES BUYER PUSHES ART-AUCTION PRICES TO LIMIT

A new species of auction goer—people of recently acquired wealth who have become high-stakes collectors of art—are responsible in large part for the series of record-shattering art auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s that took in more than $155 million in the last two weeks.

The influence of these new collectors, who work in such fields as finance and real estate, has become one of the most controversial subjects in the art world—a debate fueled by the prices of this month’s auctions. At the top of the record-setting sales for a two-week period were a Leonardo sketch for $3.6 million, a Mondrian painting for $5 million and a work by the contemporary artist Jasper Johns for $3.6 million.

Art has been collected as investment for at least the last three decades, and experts agree that several other factors besides the new collectors played a role in creating an environment ripe for sales of such proportions. Prime among them were changing tax laws that take effect Jan. 1, after which capital gains will be taxed at a higher level.

In addition, a weakness of the dollar against several foreign currencies, especially the yen, has increased the number of foreign buyers at the auctions. One of the highest prices in the recent sales, for instance, the $5 million for the Mondrian, was offered by a New York dealer bidding for a group of private Japanese collectors.

OBITUARY

FEBRUARY 23, 1987

ANDY WARHOL, POP ARTIST, DIES

Andy Warhol, a founder of Pop Art whose paintings and prints of Presidents, movie stars, soup cans and other icons of America made him one of the most famous artists in the world, died yesterday. He was believed to be 58 years old.

The artist died at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center in Manhattan, where he underwent gall bladder surgery Saturday. His condition was stable after the operation, according to a hospital spokeswoman, Ricki Glantz, but he had a heart attack in his sleep around 5:30 A.M.

Though best known for his earliest works—including his silk-screen image of a Campbell’s soup can and a wood sculpture painted like a box of Brillo pads—Mr. Warhol’s career included successful forays into photography, movie making, writing and magazine publishing.

He founded Interview magazine in 1969, and in recent years both he and his work were increasingly in the public eye—on national magazine covers, in society columns and in television advertisements for computers, cars, cameras and liquors.

In all these endeavors, Mr. Warhol’s keenest talents were for attracting publicity, for uttering the unforgettable quote and for finding the single visual image that would most shock and endure. That his art could attract and maintain the public interest made him among the most influential and widely emulated artists of his time.

Although himself shy and quiet, Mr. Warhol attracted dozens of followers who were anything but quiet, and the combination of his genius and their energy produced dozens of notorious events throughout his career. In the mid-1960’s, he sometimes sent a Warhol look alike to speak for him at lecture engagements, and his Manhattan studio, “the Factory,” was a legendary hangout for other artists and hangers-on.

In the 1980’s, after a relatively quiet period in his career, Mr. Warhol burst back onto the contemporary art scene as a mentor and friend to young artists, including Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Jean Michel Basquiat.

“He had this wry, sardonic knack for dismissing history and putting his finger on public taste, which to me was evidence of living in the present,” said the sculptor George Segal. “Every generation of artists has the huge problem of finding their own language and talking about their own experience. He was out front with several others of his generation in pinning down how it was to live in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s.”

In his book, “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol,” the artist wrote a short chapter entitled “Death” that consisted almost entirely of these words: “I’m so sorry to hear about it. I just thought that things were magic and that it would never happen.”

PROTECTING ‘NEW’ SISTINE CEILING: A DEBATE FLARES

More than midway through their 12-year project, the restorers of the Sistine Chapel frescoes seem to have dampened a debate over the use of solvents to strip away old varnish and five centuries’ accumulation of soot.

But the controversy seems to have entered a new phase, this time over how best to protect what now is being revealed. Some critics contend that as the Michelangelo masterpiece is exposed again to the light, it also faces greater exposure to humidity and airborne pollutants that could damage the frescoes.

The Vatican’s restoration project, begun in 1980, was sure to generate debates if only because it is altering the appearance of one of the world’s best-known masterpieces, Michelangelo’s epic depiction of history from the world’s creation to its end.

The restoration is being done one section at a time. This summer the workers will reach the “Creation of Adam,” which, with its outstretched hands, is perhaps the most famous pictorial image produced by Western culture.

Disagreements began over the removal of the 16th-century animal glue varnish that had combined with candle soot and dust to form a dark patina over the plaster. Critics protested that the workers’ solvents were wiping away some of Michelangelo’s original work and that, since no new protective coating is being applied in place of the old varnish, the frescoes could be damaged by exposure to the air.

The Vatican commissioned a study of the Sistine Chapel in 1982 and 1983 by Dario Camuffo, a physicist at Italy’s National Research Council. Mr. Camuffo measured the variations in temperature and humidity caused when tourists crowd into the chapel for a few hours a day.

With an average of about 6,000, and a maximum of up to 18,000, visitors a day crowding through the chapel, Mr. Camuffo said the frescoes were constantly being weakened and that tiny cracks were spreading across the plaster. He said a major cause of these cracks was the changes in temperature and humidity caused by the crowds.

So far, the Vatican has put into effect some, but not all, of Mr. Camuffo’s recommendations. Low-heat lighting has been installed, and so has an electrostatic carpet that collects dust from tourists’ shoes. He also recommended that tourists be prohibited from carrying wet umbrellas and raincoats into the chapel, but this point was rejected.

According to Walter Persegati, secretary-treasurer of the Vatican Museums, the system will control temperature and humidity and thoroughly filter the air going into the chapel.

Those who share this view say they believe the Vatican will eventually have to limit the influx of warm, humid human bodies that perhaps pose the greatest danger to the frescoes.

Restricting public access to the chapel is something that the Vatican has been unwilling to consider so far, and if other alternatives, like the climate control system, do not succeed, the guardians of Michelangelo’s frescoes may have to face an extremely difficult decision.

NOVEMBER 12, 1987

Van Gogh’s ‘Irises’ Sells for $53.9 Million

Van Gogh’s glowing “Irises”—painted in 1889 during the artist’s first week at the asylum at St.-Remy—was sold at Sotheby’s in New York last night for $53.9 million, the highest price ever paid for an artwork at auction.

The fierce bidding for the Van Gogh masterpiece was witnessed by an international gathering of about 2,200 collectors, dealers, museum curators and officials, a standing-room-only crowd that watched the proceedings in person and over closed-circuit television. Taking bids by telephone at the front of the room were two Sotheby’s employees, David Nash, head of fine-art sales, and Geraldine Nager, who is in the bids department.

Buyers bid for Vincent Van Gogh’s “Irises” at an auction at Sotheby’s in New York on November 11, 1987.

There was a gasp throughout the room as John L. Marion, chairman of Sotheby’s North America and the auctioneer, began the bidding at $15 million. Bidding progressed in $1-million increments between the two telephones and was sold to Mr. Nash, who was bidding for a European agent of an unidentified collector.

These are the 10 most expensive works of art sold at auction. Dollar figures are as of the date of the sale.

1. “Irises” by Van Gogh. Sotheby’s New York. 1987. $53.9 million.

2. “Sunflowers” by Van Gogh. Christie’s London. 1987. $39.9 million.

3. “The Bridge of Trinquetaille” by Van Gogh. Christie’s London. 1987. $20.2 million.

4. The Gospels of Henry the Lion, a 12th-century illumionated manuscript. Sotheby’s London. 1983. $11.9 million.

5. “Adoration of the Magi” by Mantegna. Christie’s London. 1985. $8.1 million, or $10.4 million.

6. “Rue Mosnier With Street Pavers” by Manet. Christie’s London. 1966. $7.7 million, or $11 million.

7. “Portrait of a Young Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed Cloak” by Rembrandt. Sotheby’s London. 1986. $10.3 million.

8. “Seascape: Folkestone” by Turner. Sotheby’s London. 1984. $10 million.

9. “Landscape With Rising Sun,” by Van Gogh. Sotheby’s New York. 1985. $9.9 million.

10. “Woman Reading” by Braque. Sotheby’s London. 1986. $9.5 million.

AUGUST 15, 1988

Jean Michel Basquiat, 27, An Artist of Words And Angular Images

Jean Michel Basquiat, a Brooklyn-born artist whose brief career leaped from graffiti scrawled on SoHo foundations to one-man shows in galleries around the world, died Friday at his home in the East Village. He was 27 years old.

A woman looks at Jean Michel Basquiat’s “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Derelict” at the Modern Arts museum in Paris.

NOVEMBER 13, 1988

80’S DESIGN:

WALLOWING IN OPULENCE AND LUXURY

The architecture of the last decade has been marked by a consistently high level of concern for appearances; it has been lavish in its use of materials, active in its use of ornament, and highly dependent on the forms of history, particularly those of classicism.

This has been a decade—and here we come back, inevitably, to the fact of these having been the Reagan years—in which architecture has been luxurious, even sumptuous, but in which it has also been not a little self-indulgent. These have been great years for the marble shippers of Italy and the granite quarries of New England; the office buildings of the 1980’s have been celebrations of luxury such as we have not seen for half a century. Opulence has been the order of the day—from the A.T.& T. Building by Philip Johnson and John Burgee in New York; to the same architects’ towers in Boston, Chicago, Houston and Dallas; to buildings such as Kohn Pedersen Fox’s Procter & Gamble headquarters in Cincinnati, Edward Larrabee Barnes’s Equitable Tower in New York, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s modestly named One Magnificent Mile in Chicago.

Some of these buildings have been good and some of them have been terrible, but taken as a group, the good and the bad present a remarkable sense of a time concerned primarily with recapturing a sense of lavishness from the past.

Post-modernism began, after all, a decade or more before the Reagan era, with the work of such theorists as Robert Venturi, who one presumes would be appalled to think of any connection between his ideas and the conservative tastes of the Reagan years. He was arguing against the utopianism of modernism, and against its austerity and indifference to popular taste; his alternative, of course, was a highly studied architecture that comments ironically on the architecture of the past and, in its irony, asserts itself firmly as work of our time.

Post-modern architects began by looking at the past to seek to express connections to a broader culture that modern architecture had denied them; by the mid-1980’s, many of them were looking back just for the ease and comfort of it. The career of Robert A. M. Stern stands as a perfect example of this: a student of Robert Venturi, Mr. Stern in the 1970’s sprinkled his work with Venturiesque irony. But in the 1980’s he became more and more a designer of lavish, highly traditional houses for the well-to-do; he moved from commenting on the Shingle Style to attempting to echo its forms literally. In the last couple of years, Mr. Stern has designed sumptuous Georgian and Shingle Style mansions that could almost pass for leftovers from the 1920’s.

OPPULENCE HAS BEEN THE ORDER OF THE DAY

Perhaps the real design symbol of these years has not been Philip Johnson or Robert Stern but Ralph Lauren, who produces impeccable stage sets of traditional design; they exude luxury and ease. Ralph Lauren has become a kind of one-man Bauhaus, a producer of everything from fabrics to furniture to buildings, all of which, taken together, form a composite, a fully designed life. But where the Bauhaus sought to challenge established standards, to break out of the bourgeois symbols of the age, Ralph Lauren celebrates them. Design is not a matter of challenge but of comfort.

The challenge of the next decade will not be to supplant post-modernism but to bring it back to its beginnings—to try to re-establish the connection between post-modernism and seriousness of intent that Robert Venturi gave it in its beginnings, while not losing sight of the social goals that have become more important in the last couple of years. It is not an easy agenda—but there never was anything easy about making architecture in the real world, in this time or any other.

Pei Pyramid and New Louvre Open Today

PARIS, March 25–Not since Gustave Eiffel made the first climb to the top of his tower 100 years ago has the inauguration of a structure in Paris been as eagerly awaited as the opening of I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid in the middle of the courtyard of the Louvre.

And Wednesday afternoon, more than five years after the unveiling of its design provoked international controversy and accusations that an American architect was destroying the very heart of Paris, President Francois Mitterrand is to quietly snip a ribbon, officially opening the pyramid.

The news from Paris is that the Louvre is still there, although it is now a dramatically different museum. The pyramid does not so much alter the Louvre as hover gently beside it, coexisting as if it came from another dimension.

The pyramid itself is a technological tour de force: it is exquisitely detailed, light and nearly transparent. Yet it is also a monument intended to take its place in the city’s grandly scaled urban fabric, a structure that, for all its overt modernism, has a strictly geometric formal quality that ties it to the Parisian cityscape.

The story of this 71-foot-high structure of glass and metal, which now serves as the main public entrance to a significantly remodeled Louvre, bears other resemblances to that of the Eiffel Tower. Like the tower, the pyramid was at first bitterly denounced by many prominent people in the arts, who viewed it as an unwelcome intrusion of harsh modernism into the sacred precincts of Paris. But also as with the tower, the Parisian mood mellowed as construction proceeded. Now that the pyramid is finished, its sharpest critics seem to have retreated, and it has become fashionable in this city not only to accept the building but even to express genuine enthusiasm for it.

The vast new underground Louvre contains a 29-foot-high main hall beneath the glass pyramid, shops, cafeterias, an auditorium and education and information facilities for visitors, and storage and work areas for the staff.

Beginning Thursday, the first day the public will be admitted to the renovated Louvre, visitors will enter the museum through the pyramid, stopping first on a triangular ground-level entry platform, then descending via an escalator, a spiral staircase or a round open platform elevator to the new main vestibule, called the Hall Napoleon.

JUNE 14, 1989

CORCORAN, TO FOIL DISPUTE, DROPS MAPPLETHORPE SHOW

The Corcoran Gallery of Art has canceled a planned retrospective of the work of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, anticipating that its content would trigger a political storm on Capitol Hill.

“Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” an exhibition of more than 150 works, many of them explicit homoerotic and violent images, was partly financed with a grant of $30,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts, an agency already under fire from Congress for its grant policies. The exhibition was to have opened on July 1.

“Citizen and Congressional concerns—on both sides of the issue of public funds supporting controversial art—are now pulling the Corcoran into the political domain,” said the director of the Corcoran, Dr. Christina Orr-Cahall.

Organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, the show has appeared in Philadelphia and Chicago, and is to travel to Hartford; Berkeley, Calif.; and Boston. Another extensive exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s work was on view last year at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan. The photographer died of AIDS in March at the age of 42.

Dr. Orr-Cahall said that the gallery had not yet received Congressional pressure, but that gallery officials had been “monitoring” the situation and felt that a major Congressional dispute was shaping up over the National Endowment’s support of the exhibition. The Corcoran received $292,000 in Federal funds in 1988 and the gallery is involved in a campaign to increase its endowment from $2 million to $12.5 million.

The controversy comes at a time when the arts endowment’s budget is up for review and it faces reauthorization legislation. The endowment has been severely criticized in recent months by members of Congress regarding a grant made to an artist through the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. The work under fire, by Andres Serrano, is a photograph of Christ on a crucifix submerged in the artist’s urine.

Senator Alfonse M. D’Amato, Republican of New York, took to the floor of the Senate on May 18 to express outrage. Twenty-five members of the Senate, across the political spectrum, co-signed a letter written by Senator D’Amato to Hugh Southern, the acting chairman of the arts endowment, asking that the endowment change its procedures.

Senator Jesse Helms, a Republican of North Carolina, joined with Mr. D’Amato on the Senate floor in expressing his outrage over the Serrano photograph and “the blasphemy of the so-called artwork.”

“I’m appalled by the decision,” said the director of the Washington Project, Jock Reynolds. “It is an outright cave-in to conservative political forces who are once again trying to muzzle freedom of expression in the arts. The Corcoran should look to the inscription that is carved over its entrance: ‘Dedicated to Art.’ They should stand by their motto and let Mapplethorpe’s work speak for itself.”

APRIL 5, 1981

London Literary Life; Let Me In, Let Me In!

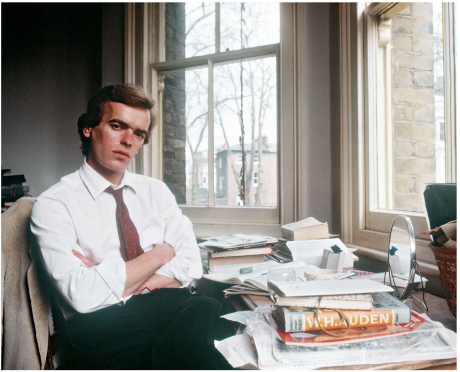

Not long ago, I traveled to Cambridge to give a reading from a novel I had just published. In the pub afterward, surrounded by pleasantly deferential students, I was asked about the London literary world. The students’ preconceptions about London were, of course, as naive and fantastic as were mine about Cambridge: “Is Clive James really a millionaire? Do you know Angus Wilson? Is Ian McEwan really having an affair with Princess Margaret?” I exaggerate, but the questions all presupposed a febrile metropolis of vast monetary gain, blazing celebrity and keen socio-sexual selfbetterment.

The London literary world does not exist. The London literary world is chimerical. “I am a chimera,” I always think, when people assume I belong to it. The London literary world is a collective fantasy of eager literary aspirants, and the fantasy contains strong elements of paranoia.

Years ago I made the mistake of writing the “One Man’s Week” guest column in the London Sunday Times. In this article I described a regular London lunch which is informally attended by myself, one or two novelists, a cartoonist, the odd poet and assorted literary layabouts. The piece was written in terms of comic hyperbole’a London literary lunch as it might be imagined by, say, an embittered provincial schoolmaster with a crate of unpublished novels in his garden shed. Under the restaurant’s sparkling chandeliers, the assembled tricksters and careerists gorged themselves on expensive food and drink, offering bribes to venal literary editors, crafting ecstatic reviews of each other’s books, condemning rivals to obscurity, hollering at the waiters, staggering out drunk at 5 o’clock, and so on.

Martin Amis poses at home on September 25, 1987, in London, England.

Practically everyone took the piece seriously as a confession or a boast. At last, people thought, they’re coming out into the open.

“I was only kidding,” I pleaded but to no avail. In a sense, the lesson of this literary sketch, and its attendant hate mail, is an old one: Never overestimate the obviousness of your own irony. But perhaps the response also reflects a general hunger to believe in an elite that coldly excludes oneself. Would-be writers may actually prefer to think of the London literary world as a hive of toadyism and malpractice. Such an impression adds considerable poignancy to the presupposition of neglect.

In the British view of the trans-Atlantic literary world, the beleaguered poets and novelists of America live in turreted fortresses or are reduced to spectral, subterranean existences. This version exaggerates reality, but suggests real differences too. When Norman Mailer published “The Naked and the Dead,” he instantly saw himself as “a node in a new electronic landscape of celebrity, personality and status.”

But there is no such landscape in England. There can be no more than half-a-dozen serious British writers who could live by their books alone. We are always forced out into the world mainly because we are looking for extra work. Here we tangle with the odd overzealous fan, and with each other; but there is no feeling of intellectual community or consensus. We are just a lot of people writing in rooms and meeting occasionally for lunch.

MARCH 2, 1980

THE PACKAGING OF JUDITH KRANTZ

In a publishing world worried about huge sums paid to popular writers, the author of “Scruples” has sold the reprint rights to her novel, “Princess Daisy,” for a record $3.2 million.

PULITZER NOVEL’S PUBLICATION IS TALE IN ITSELF

NEW ORLEANS, April 14–“I don’t like fame,” 79-year-old Thelma Toole said. “But I’m happy for my son.” Her unrelenting belief in the writing of John Kennedy Toole, her late son, led to the publication last year of a manuscript over which he had toiled for years and, yesterday, to the crowning of his work with a Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

“I was in a transcendental mood because I had tried for so many years,” Mrs. Toole, a retired teacher of the dramatic arts, said in summing up nearly 15 years of struggle that resulted in the publication of the book, a comic novel about life in New Orleans entitled “A Confederacy of Dunces.”

The book was praised in The New York Times Book Review as “a masterwork of comedy” and it was selected by The Los Angeles Times as one of the five best novels of the year. The Chicago Sun-Times called it “a foot-stomping wonder.”

The story behind this book is perhaps a familiar one, up to a point. It is of an unknown young writer convinced that he can be an author and of his romance with a New York publishing company. His inability to win publication is believed by his mother to have contributed to his suicide in March 1969 at the age of 32.

“It’s beautiful and it’s full of pain and anxiety,” Mrs. Toole said of the entire experience, ranging from the time her son presented her with a manuscript he wrote while in the Army through the very moments that she recalled the ordeal here today for a reporter, occasionally interrupting her account to answer the phone.

The time was in the mid-1960’s, when prospects were perhaps not the greatest for a manuscript focusing on the life of poor whites and their encounters with the rest of New Orleans society. But John Toole set out to have his manuscript published with one house only—Simon & Schuster.

The manuscript came to Robert A. Gottlieb, at the time an editor at Simon & Schuster. Mr. Gottlieb, now president and editor in chief of Albert A. Knopf, contacted this afternoon by telephone, said that he did not remember the man, the manuscript or the book.

As Mrs. Toole explains it, the writer-editor relationship kept her son John “on tenterhooks” for some months before he accepted repeated suggestions for manuscript changes by Mr. Gottlieb.

“Gottlieb would write and say the manuscript needed work but it still would not sell,” said Mrs. Toole.

After nearly two years, her son asked for the manuscript back. It sat dormant for nearly three years and in 1969, while in Biloxi, Miss., John Kennedy Toole died in his car of carbon monoxide poisoning. The death was ruled a suicide.

“After my son died, I took the manuscript and said to myself ‘something has to be done,’” said Mrs. Toole. She tried several other publishers but had no luck.

She then turned to the novelist Walker Percy, who was teaching a creative writing course at Loyola University in New Orleans. “I suppose I put forth such a fervent plea, I suppose he might have been touched,” said Mrs. Toole. A week later Mr. Percy sent a postcard praising the book. Eventually, he helped secure its publication by the Louisiana State University Press in Baton Rouge, the state capital, about 75 miles from here.

“When I got the book in my hand, I called Walker and said it’s so much richer,” said Mrs. Toole. “He said that was because it was in print.”

Mr. Percy said in a brief telephone interview today that the manuscript looked “physically shabby” when he received it and he at first felt he could get rid of Mrs. Toole in relatively quick order. But, he recalled, after he started reading the manuscript he could not put it down. “It didn’t take long to recognize that there was something of quality here although I admit I felt it was a book that would only have regional appeal,” said Mr. Percy. “Frankly I was astonished at the national response.”

Mr. Percy also said that, except for editing, few changes were made in the manuscript. The book is in its sixth printing, according to officials at L.S.U. Press, with sales exceeding 45,000 copies in hardback and paperback. The movie rights have been sold.

OBITUARY

JUNE 19, 1982

JOHN CHEEVER IS DEAD AT 70;

NOVELIST WON PULITZER PRIZE

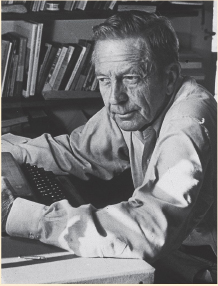

John Cheever at his home in Ossining, New York, October 1979.

John Cheever, whose poised, elegant prose established him as one of America’s finest storytellers, died yesterday at his home in Ossining, N.Y. He was 70 years old and had been afflicted with cancer for several months.

Long regarded by critics as a kind of American Chekhov, Mr. Cheever possessed the ability to find spiritual resonance in the seemingly inconsequential events of daily life.

In four novels, “The Wapshot Chronicle,” “The Wapshot Scandal,” “Bullet Park” and “Falconer,” and more than 100 short stories, he chronicled both the delights and dissonances of contemporary life with beauty and compassion.

It was an achievement recognized by a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, a National Book Critics Circle Award and the Edward MacDowell Medal. Last April he also received the National Medal for Literature, in recognition of his “distinguished and continuing contribution to American letters.”

One of the few collections of short fiction ever to make The New York Times best-seller list, his collected stories published in 1978 established him as a writer with a popular audience as well. A new novella, “Oh What a Paradise It Seems,” was published by Alfred A. Knopf last March.

His voice was the voice of a New England gentleman—generous, graceful, at times amused, and always preoccupied with the fundamental decencies of life.

“The constants that I look for,” Mr. Cheever once wrote, “are a love of light and a determination to trace some moral chain of being.”

Flooded in light—river light, morning light and late autumn light—his stories were also illuminated with a spiritual radiance. Indeed, for all his meditations on the sad, sometimes humorous inadequacies of modern America, Mr. Cheever was, at heart, a moralist, concerned with what he called “the enduring past” and the nostalgia created by memory and desire.

OCTOBER 10, 1982

A TALK WITH DON DELILLO

During the last 11 years Don DeLillo has published seven novels of wit and intelligence. He has examined advertising (“Americana,” 1971), football (“End Zone,” 1972), the rock music scene (“Great Jones Street,” 1973), science and mathematics (“Ratner’s Star,” 1976), terrorism (“Players,” 1977), the conventional espionage thriller (“Running Dog,” 1978) and, in his new novel, “The Names,” Americans living abroad.

Yet despite his unusual versatility and inventiveness, it seems that relatively few readers other than the critics clamor for Mr. DeLillo’s work. He is able to earn a living from his writing, but he has not had a large commercial success.

“I don’t know what happens out there,” he says. “I don’t know how the machinery works or what curious chemical change has to take place before that sort of thing happens. I wouldn’t speculate. I’ve always tried to maintain a certain detachment. I put everything into the book and very little into what happens after I’ve finished it.”

The best reader, is one who is most open to human possibility

Mr. DeLillo’s new novel explores how Americans work and live abroad. The protagonist, James Axton, a “risk analyst” for a company with C.I.A. ties, becomes obsessed with a bizarre murderous cult whose members select their victims by their initials.

Like “Ratner’s Star,” a book in which Mr. DeLillo says he tried to “produce a piece of mathematics,” “The Names” is complexly structured and layered. It concludes with an excerpt from a novel in progress by Axton’s 9-year-old son, Tap. Inspiration for the ending came from Atticus Lish, the young son of Mr. DeLillo’s friend Gordon Lish, an editor.

Critic Diane Johnson has written that Mr. DeLillo’s books have gone unread because “they deal with deeply shocking things about America that people would rather not face.”

“I do try to confront realities,” Mr. De-Lillo responds. “But people would rather read about their own marriages and separations and trips to Tanglewood. There’s an entire school of American fiction which might be called around-the-house-and-in-the-yard. And I think people like to read this kind of work because it adds a certain luster, a certain significance to their own lives.”

Mr. DeLillo believes that it is vital that readers make the effort. “The best reader,” he says, “is one who is most open to human possibility, to understanding the great range of plausibility in human actions. It’s not true that modern life is too fantastic to be written about successfully. It’s that the most successful work is so demanding.” It is, he adds, as though our better writers “feel that the novel’s vitality requires risks not only by them but by readers as well. Maybe it’s not writers alone who keep the novel alive but a more serious kind of reader.”

MARCH 20, 1983

Directors Join the S.E. Hinton Fan Club

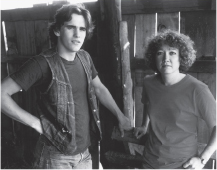

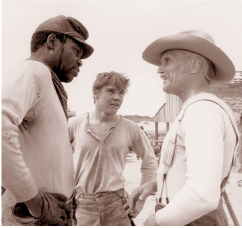

Matt Dillon with S.E. Hinton in the movie “Tex,” September 1982.

The novelist S.E. (Susan Eloise) Hinton has lived in Tulsa, Okla., for most of her 34 years. But these days she cannot help seeing her hometown as a giant movie sound stage. Three of her four books have been filmed in Tulsa in the last year and a half.

“Tex,” the first to be released, attracted good reviews last fall. “The Outsiders,” directed by Francis Coppola, opens in 800 theaters across the country on Friday.

Miss Hinton writes books for what is called the Young Adult market; her books have sold seven million copies to teenagers, and teenagers happen to be the core audience for movies these days. She is in demand because Hollywood believes that her stories can entice the kids who determine today’s blockbusters.

Both “Tex” and “The Outsiders” were turned into films because of pressure from Miss Hinton’s adolescent readers. A group of students in a California high school sent a petition to Francis Coppola stating that “The Outsiders” was their favorite book and nominating him to direct the movie version. Intrigued, Mr. Coppola asked his producer, Fred Roos, to read the novel, and Mr. Roos recommended it highly as a project for Mr. Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios.

Miss Hinton’s novelistic universe is a distinctive one. All four of her books are set in and around Tulsa, and they are unusual among teenage novels because of their sensitivity to class conflicts between rich kids and poor kids. In her stories the parents are largely absent; intense teenage friendships and sibling rivalries provide much of the dramatic material. Perhaps most surprisingly, all four books center on boys and are told from a male narrator’s point of view.

“That’s the point of view I’m most comfortable with,” Miss Hinton asserts. “When I was growing up, most of my close friends were boys. In those days, girls were mainly concerned about getting their hair done and lining their eyes. It was such a passive society. Girls got their status from their boyfriends. They weren’t interested in doing anything on their own. I didn’t understand what they were talking about.”

The reason that Miss Hinton originally used her initials rather than her full name was that she didn’t want her readers to question the authenticity of her books by knowing the author was a woman. When Matt Dillon first met her, he paid her what he thought was the ultimate compliment: “From reading your books, Susie, I thought you were a man.”

APRIL 24, 1983

SOUTHERN ACCENT GARNISHES THE PULITZER PRIZES

Pulitzer prize winning author Alice Walker, at her home in San Francisco, 1989.

Speaking with the same brutal honesty through characters seeking to control their own lives, two women of the South received Pulitzer Prizes last week—Alice Walker cited for a novel “at once political and spiritual,” and Marsha Norman for a “deeply moving” drama.

“I suppose what I was saying is this: Although we don’t get each other’s messages, we can still have faith in each other,” Miss Walker once said of her book, “The Color Purple.” The story concerns two black women: Celie, a child-wife living in the South, and her younger sister Netti, a missionary in Africa. Between world wars, they sustain themselves and each other by writing letters they never actually receive. The story focuses on Celie, at first a poor girl enslaved and abused by black men, in the end freed and endowed with a sense of self-worth by two rebellious black women. Miss Walker is the first black woman to win the fiction award.

Jessie Cates understands herself too well at the start of Miss Norman’s play, “’Night, Mother.” That is why she is intent on suicide. But not before she makes her mother, Thelma, face the emptiness of their home and daily rituals. Self-revelation, here, is a double-edged sword infinitely reflected. Jessie discovers that her interior life is “lost” but still hers to “stop, shut down, turn off,” while Thelma’s awakening to her daughter’s condition acknowledges the inexorable logic of the suicide.

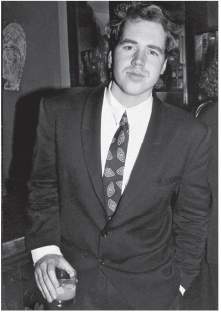

THE YOUNG AND UGLY

Bret Easton Ellis

LESS THAN ZERO. By Bret Easton Ellis. 208 pages.

This is one of the most disturbing novels I’ve read in a long time. It’s disturbing because the 20-year-old author draws a knowing portrait of adolescence that is almost entirely defined by hard drugs, kinky sex and expensive clothes. And it’s disturbing because these kids—who are as young as 13 and 14—are not only living a life out of a Harold Robbins novel, but have also acquired, at their brief age, a cynicism that makes, say, James Dean in “Rebel Without a Cause” seem like a Pollyanna.

According to the book jacket, Bret Easton Ellis is a student at Bennington College who grew up in Los Angeles, and his slick, first-person narrative encourages one to read the novel as a largely autobiographical account of what it’s like to grow up, rich and jaded, in Beverly Hills today. If Mr. Ellis’s story seems grossly sensationalistic at times—among the events described are a gang-rape of a 12-year-old girl—it also possesses an unnerving air of documentary reality, underlined by the author’s cool, deadpan prose.

The narrator, Clay, and his friends—who have names like Rip, Blair, Kim, Cliff, Trent and Alana—all drive BMW’s and Porsches, hang out at the Polo Lounge and Spago, and spend their trust funds on designer clothing, porno films and, of course, liquor and drugs. None of them, so far as the reader can tell, has any ambitions, aspirations, or interest in the world at large. And their philosophy, if they have any at all, represents a particularly nasty combination of EST and Machiavelli: “If you want something, you have the right to take it. If you want to do something, you have the right to do it.”