International politics cast a dark shadow over sports in the 1980’s. The United States, responding to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, called for an international boycott of the Summer Olympics in Moscow. Most of its allies fell in line, turning the 1980 Olympic Games into an intramural competition dominated by athletes from the Soviet Union and East Germany. In past Olympics, superpower rivalry had made the games a kind of proxy war, heightening their drama. This time, the crackling tension of West versus East was missing, and the games fell flat.

It was all the more disappointing after the unforgettable hockey finals of the winter games in Lake Placid, where the underdog Americans pulled off the “miracle on ice,” defeating a seemingly invincible Soviet team and providing one of the decade’s greatest sports moments.

USA’s Neal Broten shoots against Russia’s goalie during the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid.

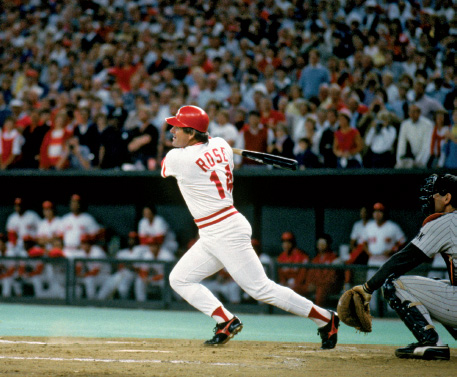

There were others. In basketball, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, playing for the Los Angeles Lakers against the Utah Jazz in 1984, sank one of his patented sky hooks for a career total of 31,420 points, breaking Wilt Chamberlain’s record. A year later, Pete Rose of the Cincinnati Reds singled to left center field off San Diego Padres pitcher Eric Show and notched his 4,192nd career hit, breaking a seemingly unreachable mark set by Ty Cobb nearly 60 years earlier. In football, Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears broke Jim Brown’s lifetime rushing record.

The Opening Ceremony at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

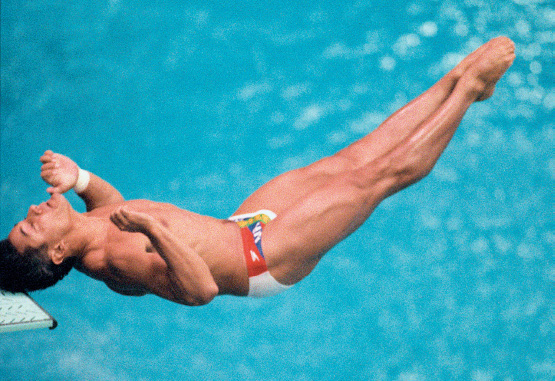

Although the Soviet Union retaliated by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, the Olympic Games continued to enthrall with dazzling performances by athletes who competed in sports well outside the mainstream. The Summer Games in Los Angeles and in Seoul four years later created a slew of stars overnight. Mary Lou Retton’s precision and power dominated women’s gymnastics. Carl Lewis put on a spectacular show in Los Angeles, equaling Jesse Owens’s record of four gold medals, as he won the 100-meter and 200-meter events and the long jump, and anchored the winning 4x100-meter relay. Greg Louganis, the picture of perfection in diving, won two gold medals at both the L.A. and Seoul games.

It was a golden age for tennis. The decade started with a grueling marathon victory by Bjorn Borg over John McEnroe to win his fifth consecutive Wimbledon title. When Borg unexpectedly retired at the age of 26, in January 1983, he left the stage open for McEnroe, ranked first in the world from 1981 through 1984, to fight it out with Jimmy Connors in a sizzling rivalry that mesmerized fans. Both yielded to the style of power tennis introduced by the Czech player Ivan Lendl.

Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe at Wimbledon in 1981.

Women’s tennis had its own superstars led by Martina Navratilova, another Czech, who seemed to own women’s tennis in the first half of the decade. From 1982 through 1984 she lost only six singles matches, and at one point maintained a winning streak of 74 matches, a record. It was not until the arrival of Steffi Graf that her iron grip on the number-one ranking was broken.

Players’ strikes plagued professional baseball and football. Baseball owners were repeatedly fined for collusion. Fans groused that the players, in the new era of free agency, were overpaid.

Allegiances shifted. For the first time, baseball could no longer claim to be America’s pastime, as football became the country’s most popular sport. One reason was the brilliant play of the San Francisco 49ers, led by quarterback Joe Montana, whose come-from-behind victories electrified fans. Exploiting an innovative passing game developed by Bill Walsh, the head coach, Montana steered the team to three Super Bowl victories in the 1980’s. A championship finish in 1989 resulted in a fourth Super Bowl win the following year.

49ers quarterback Joe Montana (left) and backup quarterback Steve Young (center) with their coach, Bill Walsh, in 1987.

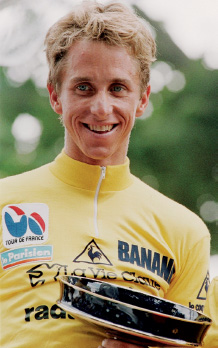

Old warriors fought on. Jack Nicklaus won his sixth Masters. Bernard Hinault took his fifth Tour de France in 1985. One year later, the unthinkable happened: Greg Le-Mond, an American despite the last name, pedaled his way to victory in the tour, becoming the first non-European to win the race since it was first held in 1903.

It was a great 10 years for sports. All of them.

U.S. DEFEATS SOVIET SQUAD IN OLYMPIC HOCKEY BY 4-3

LAKE PLACID, N.Y., FEB. 22–In one of the most startling and dramatic upsets in Olympic history, the underdog United States hockey team, composed in great part of collegians, defeated the defending champion Soviet Squad by 4-3.

The victory brought a congratulatory phone call to the dressing room from President Carter and set off fireworks over this tiny Adirondack village. The triumph also put the Americans in a commanding position to take the gold medal in the XIII Olympic Winter Games, which will end Sunday.

The US hockey team celebrates their “Miracle on Ice” victory over the USSR in 1980.

The American goal that broke the 3-3 tie tonight was scored midway through the final period by a player who typifies the make up of the American team. His name is Mike Eruzione, he is from Winthrop, Mass., he is the American team’s captain and he was plucked from the obscurity of the Toledo Blades of the International League. His opponents tonight included world-renowned starts, some of them performing in the Olympics for the third time.

The Soviet team has captured the previous four Olympic hockey tournaments, going back to 1964, and five of the last six. The only club to defeat then since 1956 was the United States team of 1960, which won the gold medal at Squaw Valley, Calif.

Few victories in American Olympic play have provoked reaction comparable to tonight’s decision at the red-seated, smallish Olympic Field House. At the final buzzer, after the fans had chanted the seconds away, fathers and mothers and friends of the United States players dashed onto the ice, hugging anyone they could find in red, white and blue uniforms.

FEBRUARY 25, 1980

U.S. Hockey Squad Captures Gold Medal

LAKE PLACID, N.Y., FEB. 24–The come-from-behind United States hockey team performed the improbable today. Amid flagwaving, foot-stomping and patriotic singing at the Olympic Field House, the Americans defeated Finland, 4-2, and won the gold medal at the XIII Olympic Winter Games.

JULY 6, 1980

BORG CAPTURES FIFTH WIMBLEDON

BEATS MCENROE IN FOUR-HOUR, 5-SET STRUGGLE

Bjorn Borg posted a five-set victory over John McEnroe today that not only gave the Swede his fifth consecutive Wimbledon singles title but also gave tennis followers something to cherish long after both players have left the sport.

Like well-conditioned fighters, they traded shots for 3 hours 53 minutes on the center court of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club. The top-seeded Borg won, 1-6, 7-5, 6-3, 6-7, 8-6, only after the determined second-seeded McEnroe had saved 7 match points in the fourth set, including 5 in a dramatic 34-point tiebreaker that will stand by itself as a patch of excellence in the game’s history.

“Electrifying,” said Fred Stolle, a former Australian great, of the tiebreaker that the 21-year-old McEnroe finally won, 18 points to 16, to deadlock the match, after Borg had earlier lost 2 match points on serve at 5-4, 40-15.

“For sure, it is the best match I have ever played at Wimbledon,” said the 24-year-old Borg, who now has won a record 35 singles matches in a row here, including five-set finals from Jimmy Connors in 1977 and Roscoe Tanner last year. Connors and Tanner, like McEnroe, are left-handers.

This one was more a struggle of indomitable wills that would not buckle, even under the normally strenuous circumstances of a championship final. Heightening the drama were the contrasting playing styles and personalities of the participants—Borg, the stolid, silent man of movement, and McEnroe, the brash, aggressive serve-and-volleyer, dubbed by one Fleet Street tabloid as “Mr. Volcano” for his outbursts during yesterday’s stormy four-set triumph over Connors in the semifinals.

Borg collected $50,000 and made his score 82 victories in his last 84 singles matches since last year’s Wimbledon final. His only losses have been to Tanner at the United States Open, which McEnroe won last September, and to Guillermo Vilas in the recent Nations Cup.

His goal, he says, is to leave the sport as No. 1 of all time. He already has achieved that distinction at Wimbledon. The records show that H. Laure Doherty won five titles between 1902 and 1906 and William Renshaw took six from 1881 to 1886. But those crowns were won during an era when defending champions played fewer matches.

AUGUST 4, 1980

Absence of U.S. Dimmed Games

The Opening ceremonies of the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow, Russia.

MOSCOW, Aug. 3–After the commotion over world records and gold medals have been digested, the XXII Olympic Summer Games will be remembered primarily for the efficient hospitality of the hosts and for the invited guests who failed to appear.

The Summer Games were in contrast to the Winter Games in Lake Placid, N.Y., where stumbling inefficiency occurred in most everything from routing buses to selling tickets. But if the abundance of manpower and machinery achieved technical brilliance, a hollow atmosphere existed throughout this fortnight. Security was so intense that almost all athletes were denied the joy of victory laps or spontaneous celebrations. The official explanation was that such exercises only tended to “provoke” spectators. In reality, allowing athletes to express their emotions might have encouraged Soviet spectators to take a more objective look at some of the foreign gold medalists and their performances.

The whistling that accompanied last Wednesday’s pole vault competition, when Wladyslaw Kozakiewicz of Poland set a world record, may have been the worse display of sportsmanship in Olympic track and field history. It was not an isolated example: Soviet crowds, perhaps spoiled by their country’s harvest of 80 gold medals, booed their soccer and basketball teams.

The boycott by the United States, West Germany, Japan, China, Canada, Kenya, and about 50 other nations had its effect. The all-white Zimbabwe women’s field hockey team, not even among the world’s top 10 won a gold medal, the first ever for the country. The East Germany took 11 pf the 14 rowing events. Judo without Japan was like New York without Bloomingdales. Horses fell so frequently during the equestrian exercises that stumbling seemed part of the program.

The Russians also may have allowed greed to tarnish an otherwise shining technical hour. Charges of officiating bias in diving, gymnastics, and track and field were as embarrassing for the various international organizers as they were for the various international federations that seemed only to willing to look the other way.

How this situation will be resolved will be an interesting question of whether the Russians and their friends decide to accept invitation to the barbecue in Los Angeles or stay home.

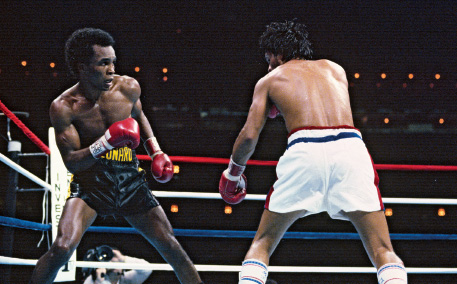

PREFIGHT FOOD SPREE AND LEONARD’S STYLE TOO MUCH FOR DURAN

Sugar Ray Leonard (left) fighting Roberto Duran (right) during at the Super Dome in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1980.

A change in Roberto Duran’s eating habits, combined with a tactical shift in Sugar Ray Leonard’s fighting style, was an apparent ingredient in Leonard’s stunning victory for the World Boxing Council’s welterweight championship last night.

Duran’s eating spree began shortly after yesterday’s noon weigh-in. Duran weighed 146 pounds, one pound under the limit. He had not eaten, his camp said, since Monday morning, when he was still overweight at 148 pounds after a steak for breakfast.

After the weigh-in, Duran finished a small thermos of hot beef broth and ate several oranges while still at the Superdome. Later, at a restaurant, he consumed almost all of two 16-ounce steaks, more oranges and close to three glasses of orange juice during a mid-afternoon meal, according to Freddie Brown, his co-trainer, and Luis Henriquez, a friend.

The fight was scheduled for 9 P.M., local time. At 5:30, said Ray Arcel, his other co-trainer, Duran ate a “small steak” in the hotel coffee shop, along with a cup of tea.

“He ate too much yesterday,” Dr. Nunez said. “After three months of having been on a strict ration, he couldn’t contain himself any longer.”

According to Dr. Nunez, Duran began cramping in the fifth round of the fight. By the seventh round, as Leonard taunted the champion, Duran had become nauseated, the doctor said.

“In the eighth round, he said he felt like he was going to throw up and faint on the floor,” Dr. Nunez related. “That is why he stopped.”

The ending marked only Duran’s second loss in 74 professional fights and the first time he had ever been stopped. It also, he said, marked the end of a pro career spanning 14 years. “I’ve gotten tired of the sport,” he said immediately after the fight. “I feel it’s time for me to retire.”

Leonard, sitting today with his son, Ray Jr., and wife, Juanita, appeared fresh and unmarked. “I mesmerized Duran,” said Leonard, whose next fight may not be until the summer of 1981, perhaps against Thomas Hearns, the unbeaten welterweight champion of the World Boxing Association. “I bewildered Duran. I made Duran lose his composure. He was completely upset.”

AUGUST 14, 1983

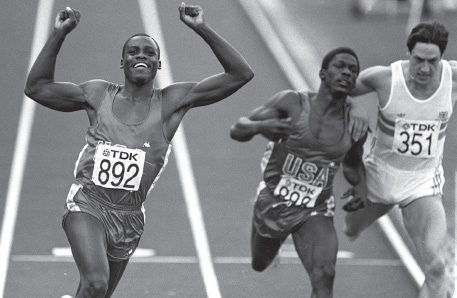

Carl Lewis Emerges: The Best At All He Does

Carl Lewis crouched in the starting blocks and positioned himself for the most important race of his career. Mind and body were ready, but Lewis’s concentration was suddenly shattered by a bee who decided to take up space in Lewis’s lane moments before the 100-meter dash final at the first world track and field championships.

Lewis flicked at the bee but then realized that he had lost his focus. Twice earlier in the year, he had allowed himself to become distracted at the start of sprint races and performed poorly. This time, at the risk of being called for a false start, Lewis calmly stood up in the blocks. Minutes later, after stumbling slightly between his second and third stride, he powered to a gold medal in the 100, only to be greeted again at the finish line by another bee.

The same bee? “I hope not,” Lewis said, several days later. “I thought I was faster than that.”

Lewis is fast, but speed is only one of the attributes that helped the 22-year-old Willingboro, N.J., athlete win three gold medals and emerge as the most talked-about competitor at this international championship.

Not since Jesse Owens won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics in 1936 has any American track and field athlete shown such versatility. “King Carl,” European periodicals proclaimed this week after Lewis’s three golds. Once finding the comparisons to Owens “difficult,” Lewis now says, in response to such overworked questions, “I don’t think it’s exaggerated because everything that’s happened has happened positively.”

Thinking positively keeps Lewis a psychological stride or two ahead of opponents. “I’m not afraid of anybody,” he said after his arrival. “The only thing I’m afraid of is that I’m not going to be the perfect athlete one day.”

USA’s Carl Lewis (left) celebrates as he crosses the line to win the gold medal at the 1983 World Athletics Championships.

Because he is so visible, what Lewis says and how he acts draws increasing scrutiny from the news media and rivals. How many times he looks around in a 100—he did so eight different times in the first three rounds, none in the final—becomes as much a part of the competition as John McEnroe questioning linesmen or Billy Martin baiting umpires. Lewis was criticized by some competitors for slowing and failing to dip down and lunge at the finish line of the 200 during The Athletics Congress national championships in June when he might easily have broken the world record. His time, 19.75 seconds, was an American record. By slowing down, some say, Lewis may be showing up the competitors he defeats.

“I’ve talked to a lot of people and the words they used were lack of sportsmanship,” said Edwin Moses, the 1976 Olympic champion and world record-holder in the 400-meter hurdles, who, unlike Lewis, prefers a more scientific attitude. “Everybody knows he’s a big winner, and nobody envies him or anything like that. But for some people, it’s a little too much.”

“To each his own,” says Leo Williams, a world class high jumper who considers Lewis a close friend. “I don’t think Carl’s intention was to make the field look bad. He said it was the joy of winning, and I believe just that. He’s sharing it. You can bet that if I jump 2.40 meters, I’m going to act the clown.” The world record is 2.37 meters, or 7-9 1/4 feet, an inch and a quarter lower.

Lewis works. Between the T.A.C. meet and this event, Lewis was clearly more interested in training than traveling around Europe picking up competition dollars, which are available to athletes through revised rules on amateur eligibility. After his arrival, when journalists wondered whether one 200-meter race since the national championships in June was sufficient preparation, Lewis said, “I’m confident in my ability, I’m confident in my technique and I’m confident in my coaching.”

OBITUARY

APRIL 13, 1981

Joe Louis, 66, Heavyweight King, Is Dead

Joe Louis, who held the heavyweight boxing championship of the world for almost 12 years and the affection of the American public for most of his adult life, died yesterday of cardiac arrest in Las Vegas, Nev. He was 66 years old.

Slow of foot but redeemingly fast of hands, Joe Louis dominated heavyweight boxing from 1937 to 1948. As world champion he defended his title 25 times, facing all challengers and fighting the best that the countries of the world could offer. In the opinion of many boxing experts, the plain, simple, unobtrusive Brown Bomber—as he was known—with his crushing left jab and hook, was probably the best heavyweight fighter of all time.

The 6-foot-1 1/2-inch, 197-pound Louis won his title June 22, 1937, in Chicago, by knocking out James J. Braddock in eight rounds, thus becoming the first black heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson, who had reigned earlier in the century. Before Louis retired undefeated as champion on March 1, 1949, his last title defense had been against Jersey Joe Walcott. Louis knocked him out on June 25, 1948, in New York.

Of the 25 title defenses, only three went the full 15 rounds. Tony Galento, for example, survived four rounds in 1939, and Buddy Baer managed one round in 1942.

Excluding exhibitions, Louis won 68 professional fights and lost only three. He scored 54 knockouts, including five in the first round.

The most spectacular victim of Louis’s robust punches was Max Schmeling, the German fighter who was personally hailed by Adolf Hitler as a paragon of Teutonic manhood. Schmeling, who had knocked out Louis in 12 rounds in 1936, was given a return bout on June 22, 1938, in Yankee Stadium. He was knocked out in 2 minutes 4 seconds of the first round.

Since 1977, Mr. Louis had been confined to a wheelchair following surgery to correct an aortic aneurysm. His health over the last decade had been poor, beset with heart problems, emotional disorders and strokes.’

MARY LOU RETTON: POWER AND FINESSE

From the tiny gold earrings in her pierced ears to the soles of her size-3 saddle shoes, 16-year-old Mary Lou Retton would seem to be a typical American teenager—a study in girlish giggles who snuggles a dogged-eared stuffed lamb, dotes on rock music and has a crush on a movie star.

Things, however, are not always what they seem.

For one thing, Miss Retton is an all-A student who is fastidious about picking up her clothes, conscientious about her household chores and never has to be reminded to do homework.

For another, she is the nation’s leading female gymnast—a diminutive dynamo of such explosive power and delicate finesse that she is considered a very strong candidate to become the first American woman to win an Olympic medal in gymnastics.

“Her vault is unbeatable—she is the best in the world,” said Bela Karolyi, the longtime coach of the Rumanian national team, who ranks Miss Retton with his former star pupil, Nadia Comaneci, who won three gold medals at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

Mary Lou Retton performs her routine on the balance beam during the 1984 Olympics.

Karolyi, who defected to the United States in 1981 and has been working with Miss Retton for the last 14 months at his school in Houston, also considers her barely beatable in the floor exercises and so good on the uneven bars and the balance beam that she could easily win the all-round Olympic championship this summer in Los Angeles.

Unlike the cool and calculating Miss Comaneci, Miss Retton is an ebullient, high-spirited competitor who radiates such sheer joy in her performances that like Miss Comaneci and Olga Korbut before her she seems ready-made to become a star in Los Angeles, according to Don Peters, the coach of the women’s Olympic team.

“She’s fantastic,” said Sylvia Cazacu, a former Rumanian coach who now works at the Manhattan Gymnastic Center on East 73d Street, where Miss Retton worked out last week. She warmed up with a couple of back flips in the tuck position, then added a twist for good measure.

In her next effort, she sprinted to the center of the mat and bounded into the air for another double-back flip, this time leaving her body extended, propellerlike, in the full layout position as she spun twice before landing on her feet—something no other woman in the world can do, according to Karolyi. “Oh, wow,” said Miss Cazacu. “Wow.”

APRIL 6, 1984

ABDUL-JABBAR SETS N.B.A. RECORD

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in 1984.

LAS VEGAS, Nev., April 5–After almost 15 splendid seasons, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tonight achieved the most important feat of his career in a fitting manner. With a 12-foot sky hook fired over a helpless defender from the right baseline, the Laker center became professional basketball’s leading career scorer.

The basket, which came with 8 minutes 53 seconds to play against the Utah Jazz at the Thomas and Mack Arena, gave Abdul-Jabbar 22 points in the game—and 31,421 for his career. That total eclipsed the 31,419 points scored by Wilt Chamberlain, who retired from the Lakers after the 1972-73 season.

The Lakers won, 129-115, before 18,389 fans. The crowd was the largest for the Jazz since the team moved west from New Orleans for the 1979-80 season.

Amid the ensuing swarm of photographers and well- wishers on the floor, the National Basketball Association commissioner, David Stern, told the crowd: “N.B.A. players are the greatest in the world. And Kareem, you are the greatest.”

Cradling the game ball, Abdul-Jabbar took the microphone and said: “It’s hard to say anything after all is said and done.”

He went on to thank his parents, who were here from New York, the remainder of his family, and the fans. He closed with an Islamic saying, which he translated. “It means God bless you and keep all of you.”

Purists may argue that Abdul-Jabbar attained the record in 15 seasons rather than the 14 in which Chamberlain did it. Or that he needed 1,166 games, 121 more than Chamberlain played. But Chamberlain also played 47,859 minutes, while Abdul-Jabbar has played only 45,625.

OLYMPICS DECISION FINAL, SOVIET SAYS

MOSCOW, May 14–The top Soviet sports official said today that the decision not to participate in the Los Angeles Olympic Games was final.

The official, Marat V. Gramov, head of the State Committee for Physical Culture and Sports, spoke at a news conference six days after Moscow announced its decision not to participate. He said the decision was made after it was concluded that the United States “cannot be expected to insure any radical change toward making the Games a festival of peace and friendship, secure for athletes.”

Mr. Gramov’s statement effectively ended speculation that the Soviet Union might reconsider its boycott, which has been joined by East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Vietnam, Laos, Mongolia and Afghanistan and is likely to include other Moscow allies.

Following the trend of the Soviet press, Mr. Gramov placed the major blame on President Reagan.

“Our nonparticipation is on the conscience of the Reagan Administration,” Mr. Gramov said, “which in the entire period of preparations for the Games did everything possible to thwart our participation.”

He insisted that what he called Soviet nonparticipation was not a boycott, and thus was not comparable to the American-led boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow after Soviet intervention in Afghanistan.

“Some Western press media describe the decision of the Soviet National Olympic Committee as a boycott,” he said. “This is absolutely untrue. Every National Olympic Committee has the right to decide whether it will attend the Games.”

Mr. Gramov did not say whether Soviet officials would attend the opening ceremonies or whether the Soviet flag would be flown.

He said the Soviet Union had no plans to organize “alternative” or “parallel” games while Olympics were being held in Los Angeles.

“This is something invented by the Americans,” he said.

JUNE 10, 1984

MISS NAVRATILOVA MAKES IT A SLAM

PARIS, June 9–Martina Navratilova overwhelmed Chris Evert Lloyd for the 11th straight time today, winning the French Open final in 63 minutes, 6-3, 6-1. In doing so, Miss Navratilova earned a bonus of $1 million and a somewhat grudging recognition as the third woman to capture the four Grand Slam events in tennis.

Miss Navratilova took control in the fourth game, as she caught Mrs. Lloyd out of position, particularly by using the drop shot, and forced her to scramble.

Mrs. Lloyd, the longtime world’s No. 1 player until displaced by Miss Navratilova, paid tribute to her conqueror, saying:

“I couldn’t find any weaknesses. I couldn’t anticipate the drop shots, I couldn’t read her. She took advantage of making me run forward, and I wasn’t quick enough. She is playing the best she has ever played. I don’t know how much better she can get.”

Miss Navratilova, who was born in Czechoslovakia and is now an American citizen, completed her consecutive sweep of the Big Four titles—Wimbledon, the United States, Australian and the French.

Miss Navratilova seems likely to dominate the circuit for some time. Asked whether having one overwhelming favorite would be bad for women’s tennis, she replied:

“I don’t think I need to play worse for women’s tennis to catch up with me. It will raise the level of play for the others. People will come out to see if I’m as good as I’m supposed to be.”

Martina Navratilova holds up her trophy after winning the French Open in 1984.

OCTOBER 8, 1984

Payton Breaks Brown’s Record

CHICAGO, Oct. 7–The moment finally came on the second play from scrimmage in the third quarter today. Jim McMahon, the Chicago Bears’ quarterback, called “Toss 28 Weak,” a pitchout for Walter Payton and a play the Bears have run countless times before.

Only this time there was something special about it.

This time, Payton ran the pitchout to his left behind the fullback Matt Suhey and the left guard Mark Bortz for a 6-yard gain and a place in history. The yards moved him him past Jim Brown to become the National Football League’s career leading rusher.

Brown, who gained 12,312 yards from 1957 through 1965 with the Cleveland Browns, had led Payton by 66 before today. Payton’s run lifted him past Brown by 5 yards, and he finished the game, a 20-7 victory over the New Orleans Saints, with 154, for a career total of 12,400 and 775 this season, the best start in his career.

Payton’s performance set another record. He ran for 100 yards or more for the 59th time; until today, he and Brown had shared the record at 58.

Payton said he felt “relieved” that the chase was finally over. After speaking by telephone for several minutes to President

Reagan, who offered his congratulations from aboard Air Force One, flying him to Louisville for tonight’s debate with Walter F. Mondale, Payton decribed how the chase had begun to bother him.

“For the past three weeks, I have tried to conceal it, but there has been a lot of pressure,” he said. “It’s been really hard to deal with; I’m glad I don’t have to do this every week. There was a lot of pressure, and if you don’t know how to deal with it, you can go astray.”

NOVEMBER 24, 1984

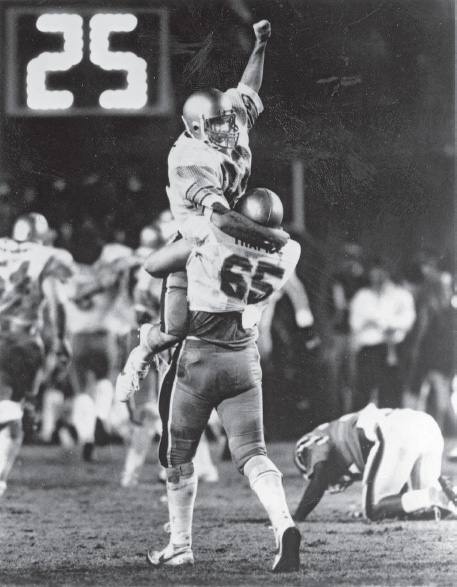

FLUTIE’S PASS ON LAST PLAY OVERCOMES MIAMI BY 47-45

MIAMI, Nov. 23–Doug Flutie enhanced his legend today with a last-play touchdown pass that soared 64 yards, just out of reach of three defenders at the goal-line and into the hands of Gerard Phelan to give Boston College a 47-45 victory over Miami.

The pass, credited as a 48-yard play, found its way to Phelan, Flutie’s roommate. Phelan somehow extracted it out of the evening mist—just as he had countless times in fantasy when the two talked about such a play in their dormitory room.

It was the last spectacular play of a spectacular game, contested on a wet day before a crowd of 30,235 in the Orange Bowl and a national television audience. The matchup was made special by the confrontation between two of college football’s most glamorous and appealing quarterbacks—Bernie Kosar, the Miami sophomore, and Flutie, the daring senior scrambler who today became the first collegian to pass for more than 10,000 yards in a career.

Doug Flutie and his teammate celebrating their Boston College’s victory over Miami.

Despite his years of heroics, which will wind up with a Cotton Bowl appearance New Year’s Day, today’s final challenge appeared to be asking a bit much of Flutie. Only 28 seconds remained when Boston College took over on its 20-yard line with Miami holding a 45-41 lead, fashioned on Melvin Bratton’s fourth touchdown.

Only 6 seconds remained when Flutie took the final snap on the Miami 48.

In the huddle, Flutie called the “Flood Tip” play. In theory, there would be two other wide receivers besides Phelan in the end zone. Phelan’s job was to tip the ball to them.

Flutie scrambled back, all the way to his 37, and then, under pressure, went to his right. Twice this season he had passed for touchdowns with no time left, but that was at halftime. This was for the game and a victory against the defending national champion.

Phelan, one of several receivers lined up right of center, was 1 yard past the goal line when the ball arrived. In front of him, three defenders tumbled over one another, attempting to get to the ball. But the other receivers were not nearby. So Phelan caught the ball himself.

“He threw it a long, long way,” Phelan said. “I didn’t think he could throw the ball that far.”

“He and I are roommates,” said Flutie, the leading candidate for this season’s Heisman Trophy, and we talk all the time about plays like this.

“I honestly believe when we ran that play we had a legitimate chance. I’m not saying that I anticipated it happening, but I’m saying we had a chance and that’s all I ask for.”

It has seemed to be all he ever needed, and some of the Miami sensed it.

One of their linebackers, George Mira Jr.—whose father is the former Miami quarterback—recalled thinking, “I had a funny feeling they were going to catch it.”

JULY 8, 1985

17-YEAR-OLD CHAMPION:

BORIS BECKER

WIMBLEDON, England, July 7–Within the span of two weeks, the 17-year-old West German Boris Becker has made history in the most famous tennis tournament in the world. Today, Becker became the youngest champion in the history of the men’s singles at Wimbledon, defeating Kevin Curren, 6-3, 6-7, 7-6, 6-4.

Playing on the most hallowed stage of tennis, Becker fit easily into his starring role here, enchanting the crowd with a booming serve and lively court acrobatics. He displayed poise in an arena that has shaken many older, more experienced players. And his zest for the game was evident as he pumped his fists or waved to the crowd; indeed, his father said that his son enjoyed tennis so much that back in his hometown of Leimen he played anyone.

Boris Becker was born on Nov. 22, 1967, in Leimen, a town a few miles south of Heidelberg in southwestern West Germany. He is the son of Karl Heinz and Elvira Becker. His father is an architect who built the tennis club where Becker learned to play as a child. At the club tonight, more than 100 people gathered to celebrate what had become a day of national pride.

“I’m the first German, and I think that will change tennis in Germany,” the younger Becker said after his victory. “They never had an idol, and now maybe they have one.”

Some residents in the town of 17,000 fired pistols in the air and hundreds of people took to the streets at 6:28 P.M., West German time, when Becker’s service winner closed out the match against Curren. “Boris Becker is now our prominent citizen,” said Mayor Kurt Weber of Leimen.

Becker’s popularity crossed the boundaries of his hometown as an estimated 20 million West Germans watched the match on television. One of the interested spectators was West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl who sent a congratulatory telegram to the teenage sensation.

“I congratulate you,” Chancellor Kohl wrote. “We are proud that you are not only the youngest Wimbledon winner but also the first German. I followed the suspenseful match on television and kept my fingers crossed. I wish you all good fortune and many more sporting successes.”

Like many European youngsters, Becker grew up playing soccer, which helped him develop the footwork that is such an important part of tennis. He is 6 feet 2 inches tall and 175 pounds, with thighs like tree trunks and a bullying style on the tennis court. He reportedly likes basketball to help condition his legs for quickness and power.

According to his father, he started playing tennis competitively at age 8, and by 11 he was playing in an area league, but in the adult divisions. When he was 12, Becker decided to concentrate on tennis.

His tennis idol, he said last week, is Bjorn Borg, the retired Swedish star who won five consecutive Wimbledon titles beginning in 1976. But he also draws some inspiration from John McEnroe, a total opposite of the stoic Borg. Becker has defended McEnroe’s brash style and, in a recent interview in a West German magazine, he said McEnroe “has a hard life” because “people come to see if he does something. If he wins normally, then they’re disappointed.”

Becker played only a few tournaments on the men’s grand-prix tour last year. He had to win three qualifying matches to enter the main draw at Wimbledon. He advanced to the third round before his ankle was twisted during a match and tendons were torn. He left the court in a wheelchair.

Even as he was recuperating, Becker toyed with his racquet, eager to practice. In January this year, he joined the tour fulltime and gradually began to move up in the rankings. At the Italian Open in Rome last May, he advanced to the semifinals.

Then the week before Wimbledon, he won his first tournament at the Queen’s Club in London. He entered Wimbledon ranked 20th in the world, and British fans made him a long-shot favorite.

Becker endeared himself to them with a boyish smile that shone under his reddish-blond hair and self-effacing humor that belied his aggressive game. Although opponents gave him little chance to win the championship, Becker smiled shyly and said, “Maybe it will be me.”

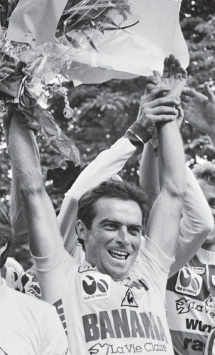

JULY 22, 1985

HINAULT WINNER AGAIN

PARIS, July 21–As nearly half a million of his fellow Frenchmen cheered, Bernard Hinault won the Tour de France bicycle race today for the fifth and, he insists, probably the last time.

His victory, after a three-week, 4,000-kilometer (2,500-mile) clockwise ride round the country equaled the record number of five set by two of the greatest champions, Jacques Anquetil and Eddy Merckx.

French Bernard Hinault, winner for the fifth time of the 72nd Tour de France cycling race in 1985.

Anquetil, a Frenchman, won in 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963 and 1964. Merckx, a Belgian, was first in 1969, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’74. His retirement ushered in the era of Hinault, who won in 1978, ’79, ‘81 and ’82 Now Hinault is approaching his 31st birthday and planning to retire after one more season. His last year, he says, will be put at the service of his Vie Claire teammate and heir apparent, Greg LeMond, an American.

Hinault was radiant when he reached the victory podium while his supporters chanted his name and a military band broke into “La Marseillaise.” His face bore few of the signs of fatigue and injury that have marked him since he crashed in a sprint and broke his nose July 13.

And, except for a long scar on the side of his right knee, his legs showed no sign of the surgery that kept him out of the 1983 tour and limited his power in 1984. “I have something to prove,” he has been saying since his second-place finish in the last tour to Laurent Fignon, who missed the race this year because of similar surgery for tendinitis.

At the start of the season Hinault set his team goals: victory in the Tour of Italy, the Tour de France and the world championships. He accomplished the first two and leaves for the United States at the end of July to ride in the Coors Classic in preparation for the world championship in Italy Sept. 1.

“After that,” Hinault said, “I am at Greg’s service.”

SEPTEMBER 12, 1985

PETE ROSE: BASEBALL’S BOUTONNIERE

CINCINNATI–With a line single in the first inning last night, baseball pinned a Rose named Pete on its lapel just when it needed something to celebrate.

Swinging left-handed with a new black bat and determined not to “go after any bad pitches,” as he had Tuesday night, 44-year-old Pete Rose lashed a 2-and-1 slider from Eric Show of the San Diego Padres for the 4,192d hit of his 23d major league season. When the ball landed in left-center field on the green artificial turf of Riverfront Stadium, the Cincinnati Reds’ manager and first baseman surpassed Ty Cobb’s record that had endured since 1928 as one of baseball’s monuments. In the seventh inning of the Reds’ 2-0 victory, Pete Rose drilled a triple into the left-field corner for his 4,193d hit. He also walked in the third and scored both runs.

Pete Rose collects hit number 4,192.

“In runs,” he would say later with a smile, “that gets me two closer to Cobb.”

The single, which occurred at 8:01 P.M. (Eastern Daylight Time), set off fireworks and a seven-minute standing ovation from 47,237 spectators in appreciation for what Pete Rose has meant to baseball. And also, in a way, for what baseball has meant to Pete Rose.

After taking a big turn at first base with his usual hustle, Pete Rose returned there as Tommy Helms, the Reds’ first-base coach, greeted him with a hug. In a rush, the Reds’ dugout emptied, the other players and the coaches hurrying to congratulate him, as did several Padre players. With them was 15-year-old Petey Rose, wearing a Reds uniform with his father’s No. 14 on the back. After having been carried upon his teammates’ shoulders, Pete Rose later could be seen wiping his eyes at the ovation.

“The only other time I remember crying was when my father died,” he would say later. “I looked up tonight and saw him up there and right behind him I saw Ty Cobb—regardless of what you think, Ty is up there. But he was sitting behind my father who was in a front-row box.”

When the other Reds retreated to the dugout, Pete Rose stood alone at first base, just as he now stood alone in total hits. But it was a new first base. The dusty bag he had stepped upon for the record hit had been removed for posterity. Now he was waving his red cap to the fans to whom he relates so well. As a youngster growing up here, he had been one of them, rooting for the Reds at old Crosley Field.

As the applause and the chant of “Pete, Pete” continued, he walked a few feet into foul territory to hug Marge Schott, the Reds’ owner.

Moments later, after emerging from a gate in the right-center-field wall, a red Corvette was driven to a stop near him—a gift from Chevrolet as a memento of the occasion. The message board diplayed the red Corvette’s Ohio license number:

“PR 4192”

As always, Pete Rose was strictly baseball. In a home-plate ceremony after the game, he wore a white baseball cap with a red commemorative logo marking his historic hit, then he spoke with President Ronald Reagan in a telephone conversation piped over the stadium’s public address system.

“Thank you for taking time out of your busy schedule to call,” Pete Rose said. “You missed a good ballgame tonight.”

When what was described as a “Rose red” Corvette was driven onto the field again, Pete Rose suggested, “Let’s call it Cincinnati Reds’ red.” And when Marge Schott presented him with a silver punch bowl set that included several silver cups, he looked toward his wife, Carol, who was with their 11-month-old son, Tyler.

“I’m sure my wife,” he said, smiling, “will enjoy polishing that once a week.”

At a time when baseball’s image as the national pastime was being battered by the testimony of several players at the Pittsburgh drug trial, Pete Rose had people talking about one of baseball’s basic appeals—a current player’s ascent above what had once been considered an old-timer’s unassailable record. Asked about the national interest in his record hit, Pete Rose nodded.

“It proves that baseball is still America’s No. 1 pastime,” he said Tuesday. “It’s the nation’s oldest game, it’s a very statistical game. People know baseball memorabilia and trivia and statistics.”

NOVEMBER 10, 1985

KASPAROV, 22, DEFEATS KARPOV FOR CHESS TITLE

MOSCOW, Nov. 9–Gary Kasparov wrested the world chess crown from Anatoly Karpov today with a stunning victory in the last game of their 14-month struggle, becoming at 22 the youngest champion in the history of the game.

Caught in an unexpected trap, Mr. Karpov, 34 years old, resigned the game and his title after 43 moves, making way for a maverick player who has electrified the chess world in his meteoric rise.

It was a game that proved a fitting finale to a grueling duel that matched any previous championship in tension, controversy and excitement.

Needing a victory to retain the title he has held for 10 years, Mr. Karpov, playing white, plunged into an aggressive king-side assault. Mr. Kasparov, leading the match, 12 points to 11, and needing only a draw to seal his victory, fashioned a Sicilian defense into a firm defensive line and seemed intent on hunkering behind it for the duration.

But the champion maintained the pressure, and suddenly Mr. Kasparov, perhaps sensing that a static defense was turning dangerous, shifted to the daring style that is his trademark.

With the clock approaching the two-and-a-half-hour limit each player has for the first 40 moves, he shifted his rooks into an offensive stance and boldly sacrificed a pawn. Then, after he advanced another pawn to be sacrificed, Mr. Karpov seemed to falter, and suddenly Mr. Kasparov had the champion in a lethal vise.

A muffled roar gathered in the crowd as Mr. Karpov tried to wriggle free. Mr. Kasparov leaned back in his chair and flashed a smile at his mother, Klara, sitting in the third row of the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall where she has been throughout the match.

Finally, Mr. Karpov offered his hand, and the capacity crowd of more than 1,000 erupted in cheers. Mr. Kasparov threw his hands over his head to shouts of “Gary! Gary!” Mrs. Kasparov, now with a bouquet of white carnations in her hand, hugged anyone who drew near.

The celebration continued in the lobby, where dark-haired Azerbaijanis from Mr. Kasparov’s native republic danced and posed for pictures with posters of their hero while sedate Karpov fans filed quietly out. More people crowded around police lines outside hoping for a glimpse of the new champion.

Since assuming the title that Bobby Fischer refused to defend in 1975, Mr. Karpov had been the model Soviet champion. An ethnic Russian, he fulfilled the civic functions asked of him in the Young Communist League and in the World Peace Committee. In his two defenses of the title, in 1978 and 1981, he salvaged Soviet honor by defeating Viktor Korchnoi, a defector.

Mr. Kasparov, by contrast, was a brash young outsider, a native of Baku in Azerbaijan, the son of a Jewish father and an Armenian mother. His father, Kim Veinshtein, died when the boy was 7, and his mother Russified her maiden name from Kasparyan to Kasparov, which the son then adopted.

The game today, with its bold sacrifices and its last-minute turnaround, was typical of Mr. Kasparov’s style. Chess fans, who are legion in the Soviet Union, find his approach more exciting than Mr. Karpov’s technical mastery, and Mr. Kasparov is perceived to be as outspoken and daring as Mr. Karpov is considered orthodox and tame.

The contrast may not be so stark. Mr. Kasparov is also a party member, and although Mr. Karpov’s political support in the Kremlin may have waned with the death of Leonid I. Brezhnev in 1982, Mr. Kasparov seems to have the backing of powerful Transcaucasians on the Politburo like Geidar A. Aliyev, a First Deputy Prime Minister, and Eduard A. Shevardnadze, the Foreign Minister.

Yet the jubilation that followed Mr. Kasparov’s victory showed that, whatever the ingredients, he is an enormously popular champion.

NICKLAUS WINS SIXTH MASTERS

AUGUSTA, Ga., April 13–Jack Nicklaus, who was four shots off the lead with four holes left, got an eagle and two birdies in those closing holes to win the Masters Tournament for a record sixth time today with a stunning 7-under-par 65.

He beat Greg Norman and Tom Kite by a single shot in what may become the most memorable of the 50 Masters played so far.

The 46-year-old Nicklaus, who was in his prime in the 1960’s and 1970’s, became the oldest man ever to win a Masters. He increased his record to 20 major tournament victories, including 18 in professional golf. No other golfer has come close to that number of major victories.

Jack Nicklaus celebrates a birdie during the US Masters Golf Tournament in 1986.

It was a classic golf charge from behind by Nicklaus, who got six birdies and the eagle at No. 15 in his last 10 holes to win with a final total of 9-under-par 279.

“This may be as fine a round of golf as I ever played, particularly those last 10 holes,” Nicklaus said. “I haven’t been this happy in six years.”

JULY 28, 1986

IN PARIS, AN AMERICAN WINS TOUR DE FRANCE

American Greg LeMond poses with his trophy in Paris after winning the 1986 Tour de France.

PARIS, July 27–Greg LeMond won the big one today: the Tour de France. The Tour is the world’s most important bicycle race, and LeMond became the first American—the first non-European—to win it since it was first held in 1903.

The 25-year-old LeMond, who lives in Sacramento, Calif. in the off season, cruised across the final finish line on the Champs-Elysees as the overall winner after racing 2,500 miles over a course that included stretches of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

He finished the race, which began July 4, in the total elapsed time of 110 hours 35 minutes 19 seconds, 3 minutes 10 seconds faster than Bernard Hinault, a French teammate on the Vie Claire team.

“Wonderful, it feels just wonderful,” LeMond said at the finish. “I was nervous, but everything went perfectly today.”

LeMond had been virtually certain of victory since Thursday, when Hinault, his longtime friend and mentor and this year his principal rival, called off a series of physical and psychological challenges he had been making in an attempt to gain a sixth, record-setting, Tour triumph.

LeMond, who has ridden for French teams since 1980 and is well known in Europe, relished the acclaim he received himself, even if he usually played second fiddle to Hinault with the news media.

“The race was fantastic and to win you’ve got to be one of the great champions,” he said today on the victory podium.

MARCH 8, 1987

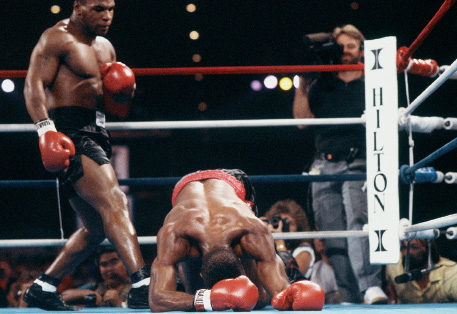

TYSON UNIFIES W.B.C.-W.B.A TITLES

LAS VEGAS, Nev., March 7–James (Bonecrusher) Smith’s chin was good, but his grip was even better. He held and held Mike Tyson and turned the advertised bout between heavyweight champion sluggers into a dreary charade of a fight.

What fight there was, Tyson won, and convincingly, as he took a unanimous 12-round decision from Smith and unified the World Boxing Council’s heavyweight title, which he already held, with the World Boxing Association title.

Tyson now has a 29-0 record, with 26 knockouts. Smith is 19-6, with 14 knockouts.

From early on, it was clear that Tyson was too big a puncher for Smith. And it was most clear to Smith, the 33-year-old fighter from Lillington, N. C. Smith abandoned any notion of winning the bout, and fought merely to survive, squeezing Tyson to his body every time the 20-year-old slugger from Catskill, N.Y., came forward winging punches aimed to end the fight quickly.

“He’s hard to hit,” Smith said afterward. “He caught me early. He’s very quick. Quicker than I thought he was.”

“I thought he was in there to win,” Tyson said. “He wasn’t fighting. He didn’t want to expose himself and put himself on the line. And I’ve got to suffer for it from the critics.” The crowd frequently booed Smith for his tactics, and Mills Lane deducted a point from Smith in rounds 2 and 8 for excessive holding.

The winner of the Tyson-Smith bout was to have fought in May against Michael Spinks, who was the International Boxing Federation champion until that organization vacated his title after Spinks refused to fight the I.B.F.’s mandatory challenger, Tony Tucker. Spinks decided to leave the Home Box Office unification series to fight Gerry Cooney, but that bout was enjoined recently by the courts. Spinks’s promoter, Butch Lewis, will be in court on Monday attempting to have the injunction overturned.

Meanwhile, the I.B.F. has ordered Tucker, its No. 1-ranked boxer, to fight James (Buster) Douglas, who is rated No. 2.

Mike Tyson watches his opponent attempt to get up during a boxing match at the Hilton in Las Vegas, Nevada.

That would leave H.B.O. with a gap in its unification series and Tyson with time on his hands. The expectation was that neither H.B.O. nor Tyson would wait for the I.B.F. title picture to be clarified and would look elsewhere for a next bout.

As the champion of both the W.B.A. and W.B.C., Tyson would have mandatory challenges of those governing bodies to meet. If an I.B.F. title bout is not scheduled in the near future, one option for the new champion would be to satisfy his mandatory obligations by fighting either the W.B.C.’s mandatory challenger, Pinklon Thomas, or the W.B.A.’s mandatory challenger, Biggs, probably in Las Vegas no later than June.

OCTOBER 25, 1987

THE POWERFUL ALLURE OF MIKE TYSON

It is the boxing match with the distinct premise as its axis that is likely to be the most profound, and in our time the boxer whose matches are most consistently fueled by such interior (if rarely articulated) logic is Mike Tyson, the youngest “undisputed” world heavyweight champion in history.

The premise underlying Tyson’s first title match, for instance, with the World Boxing Council titleholder Trevor Berbick in November 1986, which Tyson won in six brilliantly executed minutes, was that a boxer of such extreme youth (Tyson was 20 at the time, and fighting in a division in which boxers customarily mature late), who had never fought any opponent approaching Berbick’s quality, could nonetheless impose his will upon the older boxer: thus Tyson was a “challenger” in more than the usual sense of the word.

The premise underlying his title defense in Atlantic City nine days ago was something along the lines of: the 26-year-old challenger Tyrell Biggs, an Olympic gold medalist in the superheavyweight division in 1984, deserved to be punished for having enjoyed a smoother and more triumphant career as an amateur than Mike Tyson; and deserved to be punished particularly badly because, in Tyson’s words, “He didn’t show me any respect.” (Tyson said, post-fight, that he could have knocked out Biggs in the third round but chose to knock him out slowly “so that he would remember it for a long time. I wanted to hurt him real bad.”) As with the young, pre-champion Dempsey, there is the unsettling air about Tyson, with his impassive death’s-head face, his unwavering stare, and his refusal to glamorize himself in the ring—no robe, no socks, only the signature black trunks and shoes—that the violence he unleashes against his opponents is somehow just; that some hurt, some wound, some insult in his past, personal or ancestral, will be redressed in the ring; some mysterious imbalance righted. The single-mindedness of his ring style works to suggest that his grievance has the force of a natural catastrophe. That old trope, “the wrath of God,” comes to mind.

Tyson has said that he doesn’t think in the ring but acts intuitively; like his great predecessor Joe Louis, he gives the chilling impression of being a machine for hitting, and in this most rococo of his fights a machine for rapid and repeated extra-legal maneuvers—low blows, using his elbows, hitting after the bell.

I wanted to hurt him real bad

These fights do linger in the mind, sometimes obsessively, like nightmare images one can’t quite expel, but the actual experience of the fight, in the arena, is a confused, jolting, and sometimes semi-hysterical one. The reason is primary, or you might say primitive: either Tyson is hitting his man, or he is preparing to hit his man, and if nothing nasty happens within the next few seconds it will not be for Tyson’s not trying. In the average boxing match, contrary to critics’ charges of “barbarism,” “brutality,” et al., nothing much happens, as boxing aficionados affably accept, but in Tyson fights (with one obvious exception—last March’s title fight with Bonecrusher Smith) everything can happen, and sometimes does.

Thus individuals in the audience behave oddly, and involuntarily—there was even a scuffle or an actual fight at the rear of the Convention Hall during the third or fourth round, a matter of some confused alarm until security guards broke it up. Some women hid their faces, some men emitted not the stylized cries of “Hit him!” or even “Kill him!” but parrot-like shrieks that seemed to be torn from them—perhaps the “woman-like” shrieks Tyson amusingly described coming from Biggs when he was hit.

When the fight was over people remained for some minutes in their seats as if spellbound or dazed, like Biggs; or exhausted—the 20 minutes of action had seemed rather more like 20 hours.

The fight being over, the “real” world floods back, and the powerful appeal of Mike Tyson, as of his great predecessors, is that, in however artificial and delimited a context, a human being, one of us, reduced to the essence of physical strength, skill, and ingenuity, has control of his fate—if this control can manifest itself merely in the battering of another human being into absolute submission. This is not all that boxing is, but it is boxing’s secret premise: life is hard in the ring, but, there, you only get what you deserve.

AUGUST 9, 1988

THE GLOW IN WRIGLEY FIELD

Wrigley Field was lit up like an old drunk.

With it came the giddiness of the moment—the imbibing of this novelty—along with the melancholy of what was and will never be again.

Last night at 6:09 Chicago time, 540 floodlights were turned on in the old ball park and the whole historic place glowed.

Wrigley Field in Chicago, III.

With one flick of the switch in the Chicago summer dusk the Cubs suddenly were no longer the only team in the major leagues to play only day games. Now there were none. Or were there? For a long time there was a segment of the population that said night baseball was against nature.

This was a good joke, and the atmosphere for the first night game in The Friendly Confines was primarily celebratory.

It was party time, from old stars like Ernie Banks and Billy Williams throwing out the first balls, to the brass section from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra doing their thing, to bunting on the walls and facades of the park as if it were a championship or all-star game.

Then the game began, and the first batter for the Phillies, Phil Bradley, slammed a home run over the left-field bleachers. Take that Cubs, and your night-game pretensions.

It was a lovely evening, though a little warm—that is, 91 degrees.

That was only nature’s first indication that someone upstairs was out of sorts.

The Cubs took the lead, 3-1 in the third, and shortly after there was a dust storm that halted play briefly.

Then there was thunder, and then lightning, which brought oohs from the standing-room-only crowd of more than 40,000.

In the bottom of the fourth came rain—a sudden downpour—and the fans in the box seats and the players and umpires ran for shelter.

“Next,” someone said, “there will be a plague of locusts.”

As he said it, another bolt of lightning lit the night sky.

Would they ever finish the game? Would they ever complete a night game in Wrigley Field? Not on this night.

The next-to-last major league team before the Cubs to institute lights was the Tigers in then Briggs Stadium, 40 years ago.

Like many, Ray Meyer, the former De-Paul basketball coach here, said, “I never thought I’d live to see the day when Wrigley Field had lights.”

Some say that big-league baseball will never be quite the same again, with lights in Wrigley Field. Fact is, little remains the same.

Dinosaurs came and went, men’s plumed hats came and went, and even Hula Hoops came and went.

OCTOBER 01, 1988

THE SEOUL OLYMPICS;

A PLEA: SAY IT AIN’T SO, BEN

A crowd gathered outside Ben Johnson’s house today as it has every day since the athlete returned from Seoul, South Korea, on Tuesday. Many of those gathered here are sustained by the hope that Canada’s fallen athletic idol will somehow explain his drug-testing disaster in Seoul in a way that will make it possible for the nation to believe in him again.

A week after the 26-year-old Jamaican-born speedster captured the hearts of the people of his adopted country by outsprinting Carl Lewis in a 100-meter race that was one of the most ballyhooed matchups in track history, he emerged briefly from his home to wash his Ferrari. But he continued to maintain silence about the events that led to his being stripped of his gold medal and of the world record of 9.79 seconds he set in the Olympic race.

For the first time since the announcement of Johnson’s disqualification, the country awoke today to the possibility that some details may emerge. Late on Thursday evening, an attorney for the Johnson family announced that the athlete would put his version of the Seoul debacle directly to Canadians and not through the medium of a paid interview in Stern, a West German magazine that claimed to have an exclusive contract for Johnson’s story with his American business agent, Larry Heidebrecht.

The implication was that Johnson would present himself as an unknowing, or at least reluctant, participant in the events that led to the Olympic laboratory finding traces of the banned steroid stanozolol in the urine specimen taken from him after the 100-meter final.

Since his disqualification, many in Canada who know him have maintained that Johnson would not have been able to manage a drug-taking scheme on his own, and might not have known if others had been administering a drug to him. George van Zeyl, a coach with the Mazda Optimists Club, for which Johnson ran, said that he was told by people in touch with Johnson that the athlete would say that somebody with a financial interest in his success, but not Dr. George M. Astaphan, Johnson’s doctor, had been administering steroids without his knowledge.

No matter what Johnson says, it seems clear that the shock waves set off by his downfall cannot be contained without a major shake-up in Canadian track and field. The Government has hinted that the investigation it announced earlier this week may be increased to a judicial inquiry, with power to question witnesses under oath.

A primary focus of the investigation is likely to be why the Sports Ministry, the Canadian Track and Field Association and Canadian Olympic officials ignored the repeated warnings they are said to have received that steroid abuse was widespread.

THE SEOUL OLYMPICS: DIVING; LOUGANIS AT BEST IN TEST OF WILL

These Olympics tested his courage and, ultimately, his will to succeed. At the age of 28, 12 years after he made his first splash in diving—winning a silver medal in Montreal—Greg Louganis today gave what was probably the finest performance of his career in Seoul, overcoming adversity and his heir apparent, to earn a place among the great champions of the Summer Games.

It would have been easy for Louganis to settle for something less, especially after he struck his head on the springboard in a qualifying round last week, suffering a cut that required five stitches to close. Not only did he dive two more times that night to qualify, but he came back the following day to win the gold medal.

Greg Louganis of the U.S. bangs his head against the board after mistiming his dive during the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games.

Then today, when it looked as if he would have to settle for the silver in what is probably his last Olympics, Louganis stood on the 10-meter platform in a familiar pose, rubbing his face, deep in concentration, knowing he would need a near-perfect score on his final dive to overtake Xiong Ni, a 14-year-old wisp from China.

He chose a reverse three and one-half somersault, considered the most difficult dive in the sport. “I knew I was trailing going into the last dive,” Louganis said. “I knew I had a 3.4 degree of difficulty and he had a 3.2, so I had a slight advantage.”

His execution appeared flawless, Louganis piercing the water like a dart. When he is pleased with a dive, he bobs to the surface with a smile, but this time he emerged with an expression of doubt. When the scores were posted, the spectators burst into applause and Louganis, tears running down his face, ran to embrace Ron O’Brien, the United States diving coach.

“That was probably the biggest dive of his career,” O’Brien said. “To hit it like that, under those circumstances, certainly proved that he was a champion.”

Louganis received 86.70 points to finish with a total of 638.61, only 1.14 ahead of Xiong. It enabled him to become the first male to win a pair of gold medals in diving in consecutive Olympics.

Louganis said he would dive again, but probably not at this level. It is time to move on, his gold medal today the perfect exit line. “I’m looking forward to pursuing my career as an actor,” he said. “I don’t think it will be my last competition, but it may be my last world-class competition.”

APRIL 13, 1989

SUGAR RAY ROBINSON, BOXING’S ‘BEST,’ IS DEAD

Sugar Ray Robinson, the five-time world middleweight champion who was considered by many boxing experts to have been the best fighter in history, died yesterday in Culver City, Calif. He was 67 years old.

Robinson, who died at Brotman Medical Center shortly after having been admitted, was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes.

With his boxing artistry and knockout power in either fist, Robinson, who had also been the world welterweight champion, inspired the description “pound for pound, the best,” a phrase designed to transcend the various weight divisions.

“I agree with those who say Sugar Ray Robinson was the greatest,” said Don Dunphy, the longtime ringside broadcaster. “He’s my choice for number one.”

Ali, who described himself as the Greatest, acknowledged that Robinson’s “matador” style had been his inspiration in dethroning Sonny Liston as the heavyweight champion in 1964. Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, had asked Robinson to be his manager.

“You are the king, the master, my idol,” Ali was fond of saying to Robinson.

Over a quarter of a century, from 1940 to 1965, Robinson recorded 175 victories against 19 losses. Five of those losses occurred in the last six months of his career, after he turned 44 years old. He registered 110 knockouts, but he was never knocked out and he was stopped only once.

Robinson was undefeated in his first 40 bouts, with 29 knockouts. He lost a 10-round decision to Jake LaMotta in 1943, then extended his record to 128-1-2, with 84 knockouts, while ruling the welterweight division and later the middleweight division.

He earned the 160-pound middleweight title in 1951, stopping LaMotta in the 13th round. Five months later he lost the title for the first time, on a 15-round decision, to Randy Turpin in London. Two months later, at the Polo Grounds, he regained the title from Turpin in a desperate and dramatic 10th-round knockout although he was bleeding from a cut above the left eye.

At his peak, Robinson was as flashy out of the ring as he was in it. He owned a nightclub in Harlem called Sugar Ray’s, and also a drycleaning shop, a lingerie shop and a barber shop. He drove a flamingo-pink Cadillac convertible. On his boxing tours of Europe, his entourage included his valet, his barber, who doubled as his golf pro, several members of his family and George Gainford, his trainer throughout his career.

After his boxing career ended, Robinson moved to Los Angeles, where he lived comfortably but simply with his wife, Millie. He is survived by her; a son from an earlier marriage, Ray Jr.; two stepchildren, Ramona Lewis and Butch Robinson; four grandchildren, and a sister, Evelyn Nelson of New York.

Robinson’s given name was Walker Smith Jr. He was born in Detroit on May 3, 1921. He moved with his family to New York, where he grew up in Harlem. As a teenage amateur boxer representing the Salem-Crescent gym, he borrowed the Amateur Athletic Union card of another Harlem youngster named Ray Robinson. Once his Sugar Ray nickname stuck, he never used his real name.

“Sugar Ray Robinson had a nice ring to it,” he once said. “Sugar Walker Smith wouldn’t have been the same.”

APRIL 17, 1989

After 93 Die, British Again Anguish Over Soccer

At the entrance to the Hillsborough soccer stadium, where at least 93 fans died and roughly 200 were injured in a crush on Saturday, a steady trickle of mourners came today, bowing their heads in silence and placing small floral tributes to the victims at the blue wrought-iron gate.

The card on one bouquet read: “Soccer lovers of the world unite. Live in peace.”

For the troubled sport of British soccer, with its international reputation for hooliganism and crowd disturbances, the wish for tranquility would seem to be a forlorn hope.

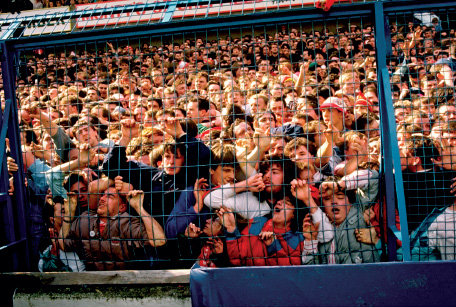

Supporters being crushed against the barrier as disaster strikes at the Hillsborough Stadium.

As Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher came to Sheffield today, announcing a full investigation and donating $850,000 of Government money to a relief fund for the victims, there is uncertainty about precisely what actions precipitated the tragedy and how it might have been prevented.

The incident occurred just after the start of a Football Association playoff match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest when Liverpool fans surged forward in overcrowded stands. The victims were crushed and suffocated in the penned-in standing area, or “terraces.”

One grim paradox of the disaster is that the fortified walls and high steel-frame fencing in the terraces, intended to control hooliganism, were a major reason that fans could not escape from the penned-in area and were crushed to death when the crowd surged forward.

In a sense, the overcrowding problem started well before the match. The Nottingham Forest side was allocated 6,000 more tickets than Liverpool, even though the average number of Liverpool fans at their games was more than twice the average gate for Nottingham Forest. The police say Liverpool was given fewer tickets in the interests of traffic and crowd control.

Even though all the 54,000 tickets for the playoff game at the neutral Sheffield stadium were sold in advance, large numbers of Liverpool fans apparently showed up at the game without tickets but hoped to gain entry, a Sheffield police officer said. Because fans do not have designated places in the standing-room terraces, it is possible to squeeze in extra spectators.

A situation of that type, a police officer at the stadium said, apparently got out of hand on Saturday. Peter Wright, Chief Police Constable for South Yorkshire, said that faced with a dangerous overcrowding problem outside the turnstiles, the police decided to let people go in just before the start of the match. Then, witnesses said, the crowd surged forward into the terrace area.

It is the standing-room terrace, a tradition at British soccer stadiums for more than a century, and still preferred by many fans, that is likely to get the closest scrutiny in the aftermath of the Sheffield disaster. “We will have to look at the future of terraces,” Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said.

MAY 22, 1989

LOPEZ BRINGS HOME THIRD L.P.G.A. TITLE

Nancy Lopez, who said she has always felt comfortable on the Grizzly Course here in Mason, Ohio, birdied five of the last eight holes today as she came from two shots back after 10 holes to win the L.P.G.A. Championship for the third time on this course. She beat Ayako Okamoto of Japan by three strokes.

Lopez, 32 years old, chipped into the cup at the 11th hole for birdie 3 and sank a 20-foot birdie putt on No. 12 to get in front. Then she stayed there and increased her lead with birdies at 14, 17 and 18 for a six-under-par 66 to defeat Okamoto, who has come close in this tournament six times but has never won a major event.

“This victory was sweet and special,” Lopez said after achieving her 40th career victory, her third in a major and her first triumph in 12 months.

Lopez, the 11th and most recent member of the Ladies Professional Golf Association Hall of Fame, was described by Okamoto as “the best woman golfer under the skies” after the triumph ended a bit of recent frustration for the champion. Lopez had played in nine events on the tour this year before this event and had finished third three times and second twice.

MAY 25, 1989

How Abbott Has Changed Baseball

Almost weekly, another photographer from another magazine will descend on Jim Abbott and ask the same question: What do you do at home?

“Not much,” the California Angels’ rookie pitcher invariably answers. “I get up, run a couple of errands and come to the yard. I play baseball.” With one hand. By now, the 21-year-old left-hander has proved to be a capable pitcher: before last night’s start against the Yankees, he had a 3-3 record with a 3.56 earned-run average. And when he returned to his Flint, Mich., home he proved that he hasn’t let all his headlines inflate him.

“Nothing’s changed,” his father said at the time. “He came in the back door and went straight to the cupboards.”

Jim Abbott may not have changed, but baseball has. For the better.

In the three months since Abbott reported to spring training as a nonroster player expected to go to a Class AA farm, this 6-foot-3-inch, 200-pound athlete has received thousands of fan letters, many from youngsters also born with only one hand. One letter was from a teenage catcher with only one leg, others from people with various physical handicaps.

His teammates don’t dare alibi their baseball mistakes when a rookie who in a split-second switches his glove from the stump of his right hand to his left hand can outpitch Roger Clemens, the two-time Cy Young Award winner, striking out four in four-hit, 5-0 shutout of the Boston Red Sox.

After that shutout, some of Abbott’s teammates created a white carpet of towels leading to his locker. But perhaps the most emotional moment of Jim Abbott’s career occurred April 24 when he was credited with his first major league victory, pitching a four-hitter through six innings in a 3-2 triumph over the Baltimore Orioles. When he got on the phone later that night with his parents, Mike and Cathy, and his 17-year-old brother, Chad, at their Flint home, he didn’t shout or brag. Instead, his voice was soft, almost subdued. “I won,” he said.

More than a game.

THE PETE ROSE CASE

Fans Are Puzzled and Dismayed

They were glad it was over, but they weren’t sure exactly how it ended. They voiced strong opinions, then asked for clarifications on the ruling. They read newspapers and listened to morning radio reports, but they still couldn’t figure out just what had happened to Pete Rose.

New York sports fans, knowledgeable and direct as they are, were in a state of confusion yesterday. When Rose, the manager of the Cincinnati Reds, was permanently banned from baseball yesterday morning by Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, the six-month investigation into Rose’s betting had reached a conclusion, but questions remained.

How could Rose be banned for life but be allowed the opportunity to apply for reinstatement after a year? How could Rose accept such a suspension and continue to deny that he ever bet on baseball?

The issue that drew the most direct responses was whether Rose, baseball’s career leader in hits with 4,256, should be voted into the Hall of Fame. Those who said Rose belonged in the Hall of Fame thought that the only criteria for induction should be performance on the field. Those who said Rose didn’t belong thought that Hall of Fame candidates should also be judged by their personal character and actions off the field.

“What Rose did off the field should have nothing to do with the Hall of Fame,” said Anthony Rogers, a 24-year-old resident of Brooklyn. “The man got more than 4,000 hits, and no one can take that away from him. There’s no question he belongs in the hall.”

“His recent actions have overshadowed his playing career,” said Richard Rosman, a 28-year-old resident of Manhattan. “I don’t think he should ever be allowed in the Hall of Fame. He has showed disregard for the game.”

Although fans expressed relief that the Rose case had been resolved before the start of the playoffs, they expressed sadness as well. Hector Delgado, a 31-year-old Manhattan street vendor who wears an Oakland Athletics cap, said he felt sorry for Rose.

“I wish I could tell him that he should have never gambled,” Delgado said. “It’s too bad. Look what he had done for the game. Just look at what he had done.”

DECEMBER 17, 1989

JOE MONTANA: STATE OF THE ART

Quarterback Joe Montana played for the 49ers from 1979-92.

In the most violent of team sports, Joe Montana is the maestro of guile and finesse. Putting his body on the line, maintaining clear vision of the entire field, throwing accurately on the run and manufacturing big plays in the game’s final, hyperventilating moments—these are among the qualities that make him the essential quarterback of his era.

And, arguably, of any era. According to the National Football League’s complex statistical formula for quarterbacks—which considers factors such as completion percentage, yards gained per pass, touchdown passes and interceptions—he is the highest-rated player ever at that position. He is also one of the most successful. Today, as the 49ers face the Buffalo Bills in the penultimate game of the regular season, they are virtually assured of their eighth playoff appearance in 11 seasons with Montana calling the signals. During that time, they have won three of four National Football Conference championship games. In the 49ers three Super Bowl victories, Montana was twice—in 1982 and 1985—named Most Valuable Player, and in last January’s contest he engineered a dramatic victory over the Cincinnati Bengals in the 49ers’ final game under Coach Bill Walsh, Montana’s mentor and the mastermind of their state-of-the-art offense.

That triumph not only validated San Francisco’s claim to the title “Team of the Decade,” but also completed a heroic personal arc for Montana, whose career was threatened in 1986 by major surgery for a ruptured disk in his back.

At the age of 33, Montana has elevated his uncanny flair for eking out last-minute victory to a level unseen since Roger Staubach stopped practicing alchemy for the Dallas Cowboys 10 years ago. It’s a mysterious trait, not a function of size or speed or strength. Most experts agree that Denver’s John Elway can heave a football farther and harder than Montana, Miami’s Dan Marino can release it more quickly and that Philadelphia’s Randall Cunningham is a better runner. “But when you talk about putting it all together—throwing, faking, leadership, running the two-minute offense—there’s still no one who touches Joe,” says Joe Theismann, the former Washington Redskins quarterback who himself played in two Super Bowls, echoing the consensus. “He’s the quarterback of the 80’s.”

Montana’s secret, football technicians say, is a complement of quarterback-specific meta-skills involving his feet, his eyes and the catchall characteristic known as “instinct.” Of course, the assessment of the experts is mostly retrospective: Montana wasn’t selected until the third round of the 1979 N.F.L. draft. Though a string of glorious comeback victories for Notre Dame hinted at his potential, his college career was erratic and injury-plagued. He was never named to an all-America team. Moreover, Montana had to overcome the conventional wisdom of those days that the prototypical pro quarterback stood 6 feet 4 and featured a high release point on his throw, the better to clear the arms of tall defensive linemen. This year, Montana has enjoyed what, in many respects, is his finest season. Even as he creeps higher on the actuarial tables for his profession, he has kept his quarterback rating well over 100—at times 20 points higher than his closest competitor—and his touchdown passes-to-interceptions ratio at an astonishing five-to-one.