IN 1956, A TWENTY-SIX-YEAR-OLD Warren Buffett formed an investment partnership to acquire small businesses and equity stakes in larger companies. In 1965, the partnership took control of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., a struggling publicly held textile manufacturer. The Buffett Partnership soon dissolved, with Berkshire shares distributed among the partners.

Today’s Berkshire Hathaway was born. Berkshire proceeded to acquire interests in diverse businesses, including insurance, manufacturing, finance, and newspapers. Despite the change from a partnership to the corporate form, Buffett has preserved the sense of partnership at Berkshire. This legacy has been reflected for decades in the first of fifteen principles stated by Berkshire in its Owner’s Manual: “Although our form is corporate, our attitude is partnership.” Berkshire differs from the typical public company model characterized by separation of share ownership from managerial control and associated agency costs.1 Rather, Buffett has been Berkshire’s controlling shareholder since 1965. He initially owned 45 percent of Berkshire’s voting and economic interest; beginning in the early 2000s, he made regular annual transfers of shares for charitable purposes that steadily reduced his interest.

Berkshire may not have needed many of the devices designed to control agency costs in public companies, such as strong oversight from an independent board. While controlling shareholders can create another set of costs for minority shareholders, Buffett has avoided imposing those costs too.

Since 1970, Buffett has served as Berkshire’s only chief executive and board chairman. Such longevity is unique. Most modern CEO tenures are far shorter. This tenure enabled Buffett to put a seemingly indelible imprint on the company. Some companies and advocates endorse age limits for officers and term limits for directors, but Berkshire’s shareholders have gained substantially thanks to Buffett’s long tenure in both roles.

Buffett’s attitude of partnership is one of profound trust. Berkshire’s Owner’s Manual, a statement of the company’s fundamental operating principles, elaborates: “We do not view the company itself as the ultimate owner of our business assets but, instead, view the company as a conduit through which our shareholders own the assets.” That view, aptly called “radical,” disintegrates the corporate veil.2

While Buffett views shareholders as the owners of Berkshire, corporate law defines them as merely owning shares of its equity—the residual interest after assets are offset by liabilities. Buffett takes the partnership conception to mean that managers are stewards of shareholder capital, accepting a higher standard of obligation than the law imposes. It is a lofty standard, like what Benjamin Cardozo said partners owe one another: “a punctilio of an honor the most sensitive.”3

In pursuing that standard, Buffett treats Berkshire’s other shareholders the way he would want to be treated if positions were reversed. In disclosure, for example, he explains business decisions faithfully, admits mistakes, and catalogues the events that have defined Berkshire culture—all in the style of an equal partner rather than a corporate chief executive.4 Buffett writes to Berkshire shareholders directly, without the filter of communications professionals, and hosts an annual meeting where he fields questions from shareholders for up to six hours straight.

Berkshire’s policies and Buffett’s explanations of them are designed to attract shareholders and business owners who agree with the Berkshire business model and its emphasis on trust.

Number Two: Munger

Buffett’s best friend and business partner, dating to the 1960s, is Charles T. Munger, who became vice chairman of Berkshire in 1978. Buffett says Munger’s presence has contributed enormous value—many billions of dollars’ worth—over the years. Buffett’s intellectual partner and confidant, Munger provides a screen: if he opposes a proposed action, Berkshire usually refrains.

Central to their prosperous relationship is their shared belief in trust as an essential element in business and corporate life. A joint belief in values like integrity and keeping promises is one facet of the Buffett-Munger relationship that makes it work.

The second facet is possessing complementary talents of temperament, attitude, and vision. Despite these distinct aspects to their relationship, such superlative business teams are more common than many think. Classic examples include Thomas S. Murphy and Daniel B. Burke at Capital Cities/ABC or Michael D. Eisner and Franklin B. Wells at Walt Disney Co.

In his book, Working Together, Eisner described his experience working with Wells, as teaching that “1 + 1 = 3.”5 Berkshire and its subsidiaries have long appreciated the power of a leadership duo. Most recently, the company has promoted two long-time managers to its board, naming them vice chairmen, in planning for the future.

Vice Chairmen: Abel and Jain

As part of Berkshire’s succession planning, in 2018, its board appointed Gregory E. Abel and Ajit Jain, two veteran company executives, as vice chairmen of Berkshire and elected them to the board. Buffett hired Jain in 1986 as an insurance executive. Then new to the field, Jain prospered instantly, forging new markets for super-catastrophic insurance and overseeing both innovative offerings and underwriting discipline. As vice chairman, he now oversees all Berkshire insurance operations.

Overseeing all noninsurance operations is Abel, who joined Berkshire upon its 1999 acquisition of MidAmerican Energy (now called Berkshire Hathaway Energy). Abel has demonstrated mastery of capital allocation, savvy in acquisitions, and appreciation of the principles of autonomy and decentralization. While growing the energy business to $25 billion in annual revenues with twenty-three thousand employees, Abel maintains a lean headquarters staff of two dozen.

The Board

Buffett’s controlling position has allowed him to nominate and elect Berkshire’s board of directors from the outset. During that time, Berkshire’s board came to assume characteristics quite different from today’s typical public companies. From the earliest decades, the board included Buffett’s late wife Susan and his close friends and, since 1993, has included his son Howard G. Buffett. It was and remains a classic advisory board, common in the United States before the corporate-governance revolution that began in the 1980s and that now is nearly extinct.6

Since the 1990s, the regulation and norms of corporate governance have shifted to increasingly define a board’s primary role as monitoring management. That means independent directors, often a powerful nonexecutive chairman, and numerous strong committees (on governance, board nominations, and CEO review) all overseeing elaborate internal control systems.

In theory, monitoring boards improved oversight on behalf of shareholders, fortified by shareholder advocates, such as institutional investor councils and shareholder advisory services. This type of regime, designed to control agency costs, is inspired by a clear lack of trust. While sometimes effective, such a regime produces the potentially inert result of “agents watching agents.” At Berkshire, this is called bureaucracy. Whatever its merits elsewhere, no such layers exist at Berkshire, and its board cannot be classified as a monitoring board.7

Berkshire’s board adheres to legal requirements concerning requisite committees, independence, and expertise. Its audit committee, for example, excludes Buffett, who, as chief executive, is not considered “independent.” The committee includes at least one financially literate member and oversees the legally mandated internal audit function. Berkshire has added numerous outside directors—that is, they are not employees and don’t have direct economic ties.

In fact, however, all are handpicked by Buffett and have personal or professional connections to him. They are chosen because of their integrity, savvy, owner orientation, and interest in Berkshire, not for their status. Indeed, half of the board members are older than sixty-five and most have served Berkshire for a decade or more. These facts would compel their departure under typical age-limit and term-limit regimes endorsed by some shareholder advocates.

Furthermore, Berkshire directors own Berkshire stock—many in large quantities. They all purchased their shares in open-market transactions paid in cash, rather than awarded by the company in stock-based compensation plans, common in corporate America. Berkshire pays its directors token fees, typically $1,000 per meeting, whereas directors at like-size companies average $250,000 per year—and even companies at the lowest end pay nearly six figures.8

Perhaps the clearest demonstration of trust is that Berkshire does not buy director liability insurance. This is unheard of in corporate America and would be impossible without the reasonable expectation that the company, or perhaps Buffett personally, would cover all reasonable losses.

Berkshire’s principal parent-level activity is accumulating and allocating capital, often making substantial acquisitions. At most companies, CEOs might formulate a general acquisition program and then present specific proposals to the board, which would then discuss deal terms and approve funding. The board’s role in this setting is an example of its service as a check on executive power.

Berkshire does the opposite, enabling Buffett to seize opportunities that would be lost if prior board involvement was required.9 Berkshire’s board, as well as the general public, knows Buffett’s philosophy of acquisitions. The board might discuss large deals in advance in conceptual terms. But it is not involved in valuing, structuring, funding, or even approving any specific acquisition. With few exceptions, the board does not find out about an acquisition until after it is publicly announced.

Berkshire’s board has two regularly scheduled meetings annually, unlike the more typical eight to twelve meetings held at other Fortune 500 companies. Formal aspects of Berkshire board meetings follow the familiar business pattern. In recent decades, succession planning has been discussed regularly at virtually every meeting.

Before each meeting, directors receive a report from Berkshire’s internal auditing team. The board’s spring meeting coincides with Berkshire’s annual shareholders’ meeting in May. Directors spend several days in Omaha, mingling with Berkshire officers, subsidiary managers, and shareholders. The fall meeting features opportunities to meet one or more CEOs of Berkshire subsidiaries, either in Omaha or at a subsidiary’s corporate headquarters. One or more CEOs make presentations and exchange ideas with the directors and fellow unit chiefs.

According to director Susan Decker, Berkshire’s approach to board meetings, as well as to Berkshire events involving directors’ participation outside of the boardroom, produces a “strong inculcation of culture.” Cynics might say such an environment promotes structural bias that can impair the independent judgment that corporate-governance advocates have hailed in recent decades.10 But this immersion of directors in Berkshire culture flattens the typical hierarchies of corporate governance, keeping directors in shareholders’ shoes.

Contemporary corporate-governance structures are skeptical of trust, insisting instead on staffing boards heavily with outsiders who are independent of chief executives. Although in compliance with the rules, the Berkshire board is quite different. In addition to having included Buffett’s late wife, the board now includes their son Howard, since 1993; Buffett’s best friend Charlie Munger, since 1978; fellow Omaha businessman Walter Scott Jr., since 1988; and Ronald L. Olson, law partner in Munger, Tolles & Olson, since 1997. Berkshire uses Olson’s law firm extensively for acquisitions and other legal work.

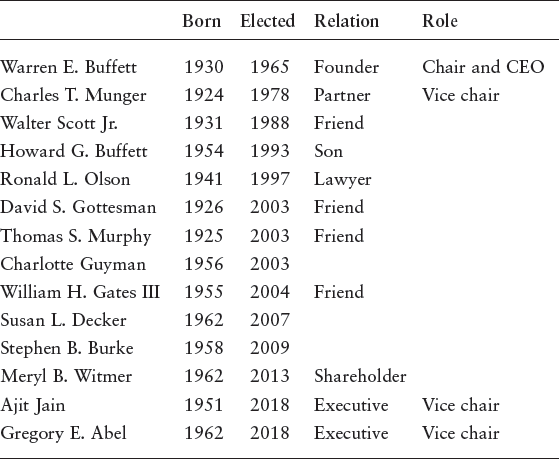

Expansions of the board in 2003 and 2004 added several long-time business associates and friends (see table 1.1). These new board members included Donald R. Keough, a veteran Coca-Cola executive, where Berkshire holds a substantial equity position, and Thomas S. Murphy, long-time chief executive of Capital Cities/ABC, another Berkshire investee. Additions also included old friends, David S. (“Sandy”) Gottesman, a New York investor and Buffett’s friend since 1962, and William (“Bill”) H. Gates III, founder of Microsoft Corporation and Buffett’s friend since 1991.

Table 1.1

Current Berkshire directors

As for stock ownership among Berkshire directors, leading the group is Gottesman, who has owned up to 3 percent of Berkshire’s interest for decades, representing a large portion—around one-fourth—of his and his firm’s portfolio. Gates comes next, with substantial personal ownership along with significant ownership through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, thanks to Buffett’s recent bequests of his shares to the charity. Others likewise tend to hold personally meaningful stakes, notably, Murphy and Meryl Witmer (part owner of Eagle Capital). In the year after his appointment as vice chairman and election to the board, Jain disclosed acquiring, for cash, some $20 million of Berkshire stock.

Berkshire’s shareholders are also unusual. They embrace the idea of Berkshire as a partnership. They believe that they are owners and relish that Berkshire has no corporate veil, no monitoring board, and no corporate bureaucracy or hierarchies. Buffett’s fellow owners resemble partners in a private firm more than shareholders of a public company. Mutual trust is the glue.

What makes these shareholders so special? Above all, Berkshire’s ownership remains dominated by individuals, not institutions. In 1965, individuals owned 80 percent of U.S. corporate equity and institutions owned 20 percent; today those figures for large public companies are reversed.11 At Berkshire, in contrast, the figures remain close to what they were in 1965.

Buffett’s individual percentage ownership is still influential, although no longer strictly controlling, after his ongoing transfers to charitable organizations. In addition to Buffett’s block, individuals control some 40 percent of Berkshire’s economic interest and voting power, making institutional investors far less important at Berkshire than elsewhere in corporate America.

At most big companies today, a changing cast of faceless financial giants owns large stakes—more than 5 percent—that, in aggregate, swamp the ownership of other owners. At Berkshire, only Buffett owns more than 5 percent of the premium Class A shares and just one giant (Fidelity) comes close.

For Class B shares, only a few giants surpass 5 percent, aggregating to more than 20 percent of that class. Given Class B’s low vote, however, this ownership adds to less than 5 percent of the voting power. Their investment rationale is formulaic: BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard run S&P index funds that necessitate holding Class B shares. (More details and the reasons for Berkshire’s dual-class structure are discussed in chapter 2.)

Berkshire’s more important institutional owners are boutique firms that have owned Berkshire for decades. They have reputations tied to Berkshire’s identity and many cater to families. From the 1970s, these owners have included Davis Funds, First Manhattan, and Ruane Cunniff’s Sequoia Fund—all led by Buffett’s friends and Berkshire aficionados. Since the 1980s, renowned value investors such as Akre Capital Management, Gardner Russo & Gardner, and Markel Corporation have also owned large stakes.

Most capital in the United States is controlled by institutions whose performance is measured pre-tax or that are tax exempt, such as foundations and pension funds. The typical Berkshire shareholder, however, including all directors and managers, is both taxable and tax conscious.

This difference helps explain Berkshire’s unusual dividend history. While most big public companies pay regular dividends that shareholders welcome, Berkshire has not paid one since 1967, and in 2014, the shareholders overwhelmingly voted against another.

Why? For one, Berkshire has been able to reinvest each dollar of earnings to generate corresponding gains in market value. But as important, dividends increase the taxable income of most Berkshire shareholders. By Berkshire reinvesting the pretax dollars, after-tax returns grow—galactically in earlier decades, but still significantly today despite the anchor of Berkshire’s enormous size. When continued for years on end, capital compounds at much higher rates, accumulating greater wealth for shareholders than if Berkshire had paid dividends.

To spread out their risk, typical institutional investors avoid concentrating portfolios in the stock of one or a few companies. Among holders who publicly disclose stakes, for instance, few of the largest hundred shareholders of blue-chip companies like Apple, ExxonMobil, or Walmart allocate more than 5 percent of their portfolios to a single company’s stock.

In contrast, many Berkshire shareholders concentrate in Berkshire shares. To illustrate, half of the one hundred largest publicly disclosed Class A owners hold more than 5 percent of their portfolio in Berkshire stock, including Buffett and several other notable individuals and boutique firms. A dozen more of the largest Class B holders are so concentrated.

Indeed, many Berkshire shares are owned by people for whom Berkshire is among their largest holdings. Many hundreds of Berkshire shareholders concentrate more than 3 percent of their portfolios in Berkshire stock, something no other large public company comes close to achieving.12

Today’s institutional investors often challenge managers to divest subsidiaries and focus on a single business. That contrasts with the Berkshire acquisition model and commitment to hold subsidiaries forever. The Berkshire shareholder embraces the diverse and permanent conglomerate, where divestitures are rare exceptions. For these shareholders, permanence builds trust; transience dissipates it.

Since at least 1993, Buffett has advised ordinary investors to use index funds rather than pick individual stocks as he and Berkshire have always done.13 Yet, since at least 1979, he has strongly advocated that Berkshire shareholders be more like him, not indexing across corporate America but rather loading up and sticking around in Berkshire stock.14 Over half a century, Buffett has consciously sought to attract only those shareholders who have the devotion and intelligence to understand Berkshire.

These are engaged investors. They devour Berkshire’s annual report and attend its shareholder meetings in droves, both rare in corporate America. They are analytical and long-term investors. They include hundreds of wealthy individuals and thousands of rich families. Among these are many billionaires, including, in addition to Buffett and Gottesman, Homer and Norton Dodge (early investors), Stewart Horejsi (acquired 4,300 shares in 1980), Bernard Sarnat (cousin-in-law of Benjamin Graham), and Walter Scott Jr. (also a Berkshire director).15

Many founders or executives of Berkshire subsidiaries became independently wealthy by building those businesses, including several ranked as Forbes 400 multibillionaires. Billionaires or near-billionaires include the following: the late Harold Alfond of Dexter Shoe, Jim Clayton of Clayton Homes, William Child of RC Willey Home Furnishings, Doris Christopher of Pampered Chef, Barnett Helzberg Jr. of Helzberg Diamonds, Lorry I. Lokey of Business Wire, Drayton McLane of McLane Company, the late Jay and Robert Pritzker of Marmon Group, Richard Santulli of NetJets, the late Al Ueltschi of FlightSafety, and Stef Wertheimer of ISCAR/IMC Companies.

Long-time Berkshire shareholder and author Andrew (“Andy”) Kilpatrick makes a practice of tracking fellow shareholders to highlight in his monumental company history, Of Permanent Value.16 By collating a small sampling from his copious research, as well as our own personal knowledge, we created the following short list of Berkshire shareholders. You will find famous investors, athletes, politicians, authors, musicians, business executives, and professors—an impressive list not likely matched by many other companies.

Some Notable Individual Investors of Berkshire

| Sid Bass |

Sen. Orrin Hatch |

Sen. Jay Rockefeller |

| Billy Beane |

LeBron James |

Alex Rodriguez |

| Sen. John Barrasso |

Shawn Jefferson |

Rep. Paul Ryan |

| Franklin Otis Booth Jr. |

Sen. Bob Kerrey |

Paul Samuelson |

| George W. Brumley III |

Billie Jean King |

Richard Scylla |

| Jimmy Buffett |

Ted Koppel |

Don Shula |

| Rep. David Camp |

Ann Landers |

George Soros |

| Glenn Close |

George Lucas |

Candy Spelling |

| Lester Crown |

Archie MacAllaster |

Roger Staubach |

| Barry Diller |

Forrest Mars Jr. |

Ben Stein |

| Sen. Dick Durbin |

Newton Minow |

Bill Tilley |

| Harvey Eisen |

Andy Musser |

Prem Watsa |

| Charles D. Ellis |

Sen. Bob Nelson |

Byron Wein |

| Marvin Hamlish |

Rep. Tom Osborne |

Dirk Ziff |

Skimming the list of Berkshire’s highly concentrated and long-term shareholders reveals some of the most distinguished investors and investment firms in America. These include shareholders who have owned substantial stakes in Berkshire for one to four decades.

The Managers

When Berkshire finds managers it trusts, it leaves them alone. At most companies, corporate tasks tend to be centralized, with divisional and sub-division heads (middle management); reporting hierarchies; systematic policies concerning budgeting, personnel; and intricate systems of procedures and practice. Such structures add overhead in the name of effective oversight.

In contrast, with the exceptions of financial reporting and internal auditing, Berkshire skips such staples of corporate life, viewing most as bureaucratic excess. Berkshire devolves these and all other internal matters to its subsidiaries. Home office overhead is negligible at Berkshire, with a staff of only two dozen. Each subsidiary maintains its own programs and policies concerning budgeting, operations, and personnel—as well as conventional departments such as accounting, compliance, human resources, legal, marketing, and technology.

Consistent with this decentralized approach, each subsidiary is led by its CEO without interference from headquarters. Berkshire defers as much responsibility as possible to subsidiary chief executives with scarcely any central supervision. All quotidian decisions qualify, including advertising budget, product features and environmental quality, and product mix and pricing.

The same applies to decisions about hiring, merchandising, inventory, and receivables management. Berkshire’s deference extends to subsidiary decisions on succession to senior positions, including unusual deference on CEO succession. Berkshire does not transfer businesses between subsidiaries and only rarely moves managers.17 Berkshire has no retirement policy and many chief executives continue working well into their seventies or eighties.

Some Quality Institutional Investors of Berkshire

| AKO Capital |

E. S. Barr |

Lourd Capital |

| Akre Capital |

Everett Harris & Co. |

Mackenzie Investments |

| Allen Holding Inc. |

Fairholme Capital |

Mar Vista |

| Aristotle Capital |

Fiduciary Management |

Markel Corporation |

| Arlington Value Capital |

Findlay Park |

Mraz, Amerine & Associates |

| Atlanta Capital Investment |

First Manhattan |

Neuberger Berman |

| Baillie Gifford & Co. |

Flossbach von Storch |

Punch Card Capital |

| Baldwin Investment |

Fort Washington Investment Advisors |

Robotti & Company |

| Barrow Hanley |

Gardner Russo & Gardner |

Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb |

| Beck, Mack & Oliver |

Giverny Capital |

Sleep, Zakaria & Co. |

| Boulder Investment Advisers |

Greylin Investment |

Smead Capital |

| Bridges Investment |

Hartford Funds |

Speece Thorson Capital |

| Broad Run |

Hartline Investment |

Sprucegrove Investment |

| Brown Brothers Harriman |

Henry H. Armstrong Associates |

Stearns Financial Services |

| Budros Ruhlin & Roe |

Hikari Tsushin |

Timucuan Asset Management |

| Burgundy Capital |

Jackson National Asset Management |

Tweedy, Browne |

| Check Capital |

Jolley Asset Management |

Wallace Capital |

| Clarkston Financial |

Klingenstein Fields |

Water Street Capital |

| Consulta Ltd. |

Lafayette Investments |

Wedgewood Partners |

| Cortland Advisors |

Lee, Danner & Bass |

Weitz Investments |

| Davis Selected Advisors |

London Company of Virginia |

WhaleRock Point |

| Douglass Winthrop |

|

Wintergreen Advisers |

| Eagle Capital |

|

|

The only qualifications on managerial autonomy at Berkshire appear in a short letter Buffett sends unit chiefs every two years. The missive states the mandates Berkshire places on subsidiary CEOs: (1) guard Berkshire’s reputation, (2) report bad news early, (3) confer about postretirement benefit changes and large capital expenditures (including acquisitions, which are encouraged), (4) adopt a fifty-year time horizon, (5) refer any opportunities for a Berkshire acquisition to Berkshire headquarters, and (6) submit written successor recommendations.18

Buffett’s directive that Berkshire CEOs designate a recommended successor explains why most Berkshire subsidiary successions are seamless. In an emergency situation in 2011, for example, David Sokol resigned from what was then MidAmerican Energy. He was succeeded by Abel, a savvy company veteran and part owner, whose team grew and rebranded the formidable firm now called Berkshire Hathaway Energy. That miniconglomerate, in turn, now owns the vast network of real-estate agents spanning the United States, the ubiquitous Berkshire Hathaway Realty.

We consider a few challenges of management succession at Berkshire’s subsidiaries in chapter 9, but the overwhelming majority have been effective. Many Berkshire subsidiaries evolved through multiple successions where successors took the company to heights undreamed of by predecessors. Pronounced examples recur in some of Berkshire’s businesses with family origins, including Clayton Homes, Jordan’s Furniture, Justin Brands, the Marmon Group, McLane, and RC Willey. Recent successions have been effective at a dozen subsidiaries, including Business Wire, Fruit of the Loom, General Reinsurance (Gen Re), Lubrizol, MiTek Systems, and Star Furniture.

Three recent successions bear special mention, given the companies and people involved: See’s Candies, GEICO, and FlightSafety International.

See’s Candies is among Berkshire’s earliest acquisitions, in 1972. It marked the change in Buffett’s investment philosophy from one obsessed with cheap purchase prices to one focused on high-quality businesses with enduring franchise value. The incumbent CEO, Chuck Huggins, remained at the helm until 2006.

Then, in an unusual move, Buffett tapped another Berkshire executive, Brad Kintsler, for the job. Kintsler had served, since 1987, in several other roles at Berkshire, including as CEO of Fechheimer Brothers, the uniform maker. Kintsler had an impressive run at See’s, maintaining the company’s boutique quality while expanding its merchandising reach nationally.

Upon Kintsler’s retirement in 2019, it was perhaps fitting that his successor, like him, was plucked from another Berkshire business. In this case, Pat Egan was tapped. Notably, Egan was formerly a senior executive in Berkshire Hathaway Energy, the business long overseen by Abel.

GEICO likewise holds a special place in Buffett and Berkshire history. It was among the first businesses Buffett studied carefully, writing an article about it in 1951; Berkshire bought a substantial percentage of GEICO in 1976 and the rest in 1995. Its long-time CEO, who retired in 2018, is a Berkshire legend: Olza M. (“Tony”) Nicely joined GEICO in 1961 at age eighteen and became CEO in 1992. Not many executives spend more than 50 years at the same company, but Nicely is one of several Berkshire executives holding that distinction.

Nicely led GEICO’s transformation. On his watch, GEICO went from a bit player in car insurance, with 2 percent of the market and paltry growth, into a powerful industry force with nearly 14 percent share. That growth translated into at least a tripling of premium volume, float, and profit.

Despite this success, Nicely never boasted nor sought the spotlight. Befitting that style, Nicely’s retirement came without fanfare—no press promotion or journalist coverage. Buffett paid Nicely a great tribute in his 2018 letter, however, also extolling the talents of his successor, long-time colleague Bill Roberts.

The FlightSafety succession is a sadder one, marking the passing of Bruce Whitman in 2018 at the age of eighty-five.19 Like Nicely, Whitman spent his career at one company, beginning in 1961 as the number two and in 2003 becoming president and CEO.

In 1996, Berkshire acquired FlightSafety, which marked a turning point for both companies and for Buffett. During 1996, Berkshire began its transformation from a minority investor in large public companies into a conglomerate, acquiring scores of businesses in diverse industries.

Specifically, since Berkshire’s acquisition of FlightSafety through today, Berkshire has made some forty-five acquisitions, at a combined cost of around $165 billion, while driving shareholders’ equity up more than $275 billion. Since 1996, Berkshire’s book value per share rose from $20,000 to $200,000; its Class A share price climbed from $35,000 to $300,000; and market capitalization soared from $60 billion to $500 billion.

Buffett attributes Berkshire’s success to its managers. In his famous annual shareholder letters, Buffett extols his subsidiary heads, aptly dubbing them the “All Stars” of American business. On several occasions, Buffett singled out accomplishments of Whitman, Nicely, and Kintsler, along with dozens of others. Buffett stresses that Berkshire CEOs, while all at the top of their fields, each play the game distinctly. As he wrote in his 2015 letter to shareholders:

Berkshire’s CEOs come in many forms. Some have MBAs; others never finished college. Some use budgets and are by-the-book types; others operate by the seat of their pants. Our team resembles a baseball squad composed of all-stars having vastly different batting styles. Changes in our line-up are seldom required.

Effective leadership transfers at Berkshire’s subsidiaries are vital to the decentralized conglomerate model. Berkshire headquarters has scant resources to intervene, so succession planning is the responsibility of the managers.

Whitman was succeeded by two colleagues, taking the titles of co-CEO and sector presidents of the pilot-training company: for commercial aviation, David Davenport, who joined FlightSafety in 1996 and worked closely with Whitman at headquarters from 2012, and for military aviation, Raymond E. Johns Jr., who retired as a U.S. Air Force general in 2013 when he joined FlightSafety and also worked closely with Whitman at headquarters.

Until Whitman’s passing, FlightSafety under Berkshire’s ownership had only one change in lineup—when founder Ueltschi passed the ball to Whitman in 2003. This succession plan was nearly foolproof, given Whitman’s decades of steadfast service leading up to it. In his 1999 memoir, The History and Future of FlightSafety International, Ueltschi explained:

The company has a small but tremendously effective corps of executives, most of whom arrived as enthusiastic youngsters and stayed for the long haul. One of the first on the scene proved to be one of the best, Executive Vice President Whitman. He has been my right-hand man since the day he arrived—a very good day for us all.

Buffett, in his 2007 annual letter, officially proclaimed Whitman’s succession totally effective.

Several other Berkshire CEOs have written autobiographies. These efforts reflect the character of their authors and are as varied as Buffett suggested. Berkshire CEO authors—including Jim Clayton and Doris Christopher—attribute their success to such different forces as imagination, empathy, and passion.

Despite the diversity among managers, all of them have emphasized the importance of trust—being trusted by Buffett and Berkshire and demanding trustworthiness from their teams. As Whitman put it: “Buffett trusts me so much with Berkshire’s money that I am even more careful in handling Berkshire capital than in handling my own.”20