For better or for worse, Arguments (logical reasoning, in LSAT-speak) questions make up half of the LSAT. For the past six years, there have been between 50 and 52 Arguments questions on the LSAT. The good news is that if you can substantially increase your Arguments performance, you’ve taken a major step toward achieving the LSAT score you need. How do you go about improving your Arguments score? Well, let’s get right to it.

The Arguments section of the LSAT tests a very useful skill: the ability to read closely and critically. It also tests your ability to break down an argument into parts, to identify flaws and methods of reasoning, and to find assumptions. Many arguments contain flaws that you have to identify to be able to get the correct answer. It’s a minefield.

Of all the sections on the test, this section relates the most to your future career as a lawyer. Evaluating an argument for its completeness, identifying assumptions, and making sound inferences are skills that will be useful to you in law school and beyond.

There are two scored Arguments sections on the LSAT. Each one will have between 24 and 26 questions, for a total of 50 to 52 Arguments questions. Some Arguments passages may be followed by two questions, although most Arguments passages, especially on recent tests, are followed by a single question. The fact that you are presented with 25 or so arguments to do in a 35-minute period indicates that the Arguments section is just as time intensive as the Games or Reading Comprehension sections.

In the next few pages, we’ll look at the general strategies you need to use during the Arguments sections of the LSAT. These pages contain a few simple rules that you must take to heart. We’ve taught hundreds of thousands of students how to work through arguments, and these strategies reflect some of the wisdom we have gained in the process.

Why should you read the question first? Because often the question will tell you what you should be looking for when you read the argument, whether it be the conclusion of the argument, a weak spot in the argument, how to diagram the argument, or something else. If you don’t read the question until after you’ve read the argument, you’ll often find that you need to read the argument again—wasting valuable time—after you learn what your task is. The question is a tip-off, so use it.

Your mantra: I will always read the question first.

Reading arguments too quickly is a recipe for disaster, even though they appear short and simple. Usually the arguments are merely three sentences, and the answer choices are just a sentence each. But their brevity can be deceptive because very often complex ideas are presented in these sentences. The answers often hinge on whether you’ve read each word correctly, especially words like not, but, or some. You should be reading as closely as if you were deconstructing Shakespeare, not as if you were reading the latest thriller on the beach. So slow down, and pay attention!

Your mantra: I will slow down and read the arguments carefully the first time.

What should you do if you read the first sentence of the argument and you don’t understand what it’s saying? Should you read sentence two? The answer is NO. Sentence two is not there to help you understand sentence one. Neither is sentence three. Neither are the answer choices—the answer choices exist to generate a bell curve, not to get you a 180. If you start reading an argument and you are confused, make sure you’re focused and read the first sentence again more slowly. If this still doesn’t help, skip it. There are 24 to 26 arguments in the section—do another one! It doesn’t matter which Arguments questions you work on, just that you do good work on those that you choose to do. Don’t waste time pounding your head against a frustrating argument if you don’t understand what it’s saying—you’ll be less able to do any good work on that question. Also, you can jeopardize your performance on subsequent questions when you lose focus by fighting with a frustrating question. The LSAT rewards confidence, so it’s important to maintain a confident mindset. Working through difficult questions when there are other, more manageable ones still available is not good form. Yes, you will feel as if you should finish the argument once you’ve invested the time to read part of it. But trust us; you’ll benefit by leaving it. Remember: You can always come back to it later when there are no better opportunities to get points. Just mark the argument so you can find it if you have time later. Come back to it when it won’t affect other questions that are more likely to yield points. After all, that’s what you’re after—points.

Your mantra: If I don’t understand the first sentence of an argument, I will skip to another argument that I do understand.

A classic question about standardized tests: Should I transfer my answers to the bubble sheet in groups, or transfer each answer after I’ve solved it? Our response: This section will have two or three arguments on the left-hand page and another two or three arguments on the right-hand page; work on all those questions and then transfer your answers before you turn the page. If you’ve left one blank, circle the argument you left blank on your test page, but bubble in an answer on your answer sheet anyway (remember: there’s no guessing penalty). Why should you do this? Because if you don’t have time to come back to it, you’ve still remembered to put an answer on your sheet (pick your favorite, your “letter of the day,” and stick with it; there’s no best letter, so just be consistent). And if you do have time to go back and work on arguments you skipped the first time around, you’ve got them handily marked in your test booklet; go back and change the answer (if necessary) for that question on the answer sheet.

Your mantra: I will transfer my answers in groups, even bubbling in answers to questions that I’m skipping for the time being.

When there are five minutes left, begin to transfer your answers one at a time. You can even skip ahead for a moment and bubble in your “letter of the day” for all the remaining questions. That way, if the proctor erroneously calls time before he or she is supposed to, or if you simply know you aren’t going to finish in time, you’ve still got an answer on your sheet for every question.

Your mantra: When five minutes are left, I will transfer answers one at a time and make sure I have bubbled in an answer to every remaining question.

Please remember to do this! You will of course feel some anxiety—this energy can actually be helpful, because it keeps your adrenaline pumping and can help keep you focused. But don’t get so stressed out that you lose the thread of reality. So, after finishing each two-page spread of arguments and transferring your answers, take 10 seconds, close your eyes, and inhale deeply three times. You’ll invest only about a minute over the course of the entire section for these short breaks, but the payback will be enormous because they will help you to stay focused and to avoid careless errors. Trust us on this one.

Your mantra: I will take a 10-second break after every five or six arguments.

The first step in tackling LSAT arguments is to make sure you’re thinking critically when you read. Maybe you’ve had a lot of practice reading critically (philosophy and literature majors, please stand up) or maybe you haven’t. Perhaps you’re out of practice if you haven’t been in an academic environment for a while. The next few pages show you on what level you need to be reading arguments to be able to answer questions correctly.

So, what is an argument? When people hear the term argument they often think of a debate between two people, with each party trying to advance his or her own view. People often are emotionally invested in an argument, and thus arguments can become heated quickly. On the LSAT, it’s crucial that you don’t develop such an emotional response to the information.

Here’s a definition of arguments that applies in LSAT-land: “An argument is the reasoned presentation of an idea that is supported by evidence that is assumed to be true.” Notice that we’ve italicized certain words for emphasis.

Let’s examine each of these in turn.

Reasoned presentation: By this we mean that the author of an LSAT argument has organized the information presented according to some kind of logical structure, however flawed the end result may be.

An idea: The conclusion of the author’s argument is really nothing more than an idea. Just because it’s on the LSAT doesn’t mean it’s valid. In fact, the only way to evaluate the validity of an author’s conclusion is to examine the evidence in support of it and decide whether the author makes any leaps of logic between the evidence and his or her conclusion.

Supported by evidence: All of the arguments on the test in which an author is advancing a conclusion—there are a few exceptions to this, which we’ll refer to as “passages” rather than “arguments”—have some kind of evidence presented in support of the author’s conclusion. That’s just the way it works.

Assumed to be true: On the LSAT we are not allowed to question the validity of the evidence presented in support of a claim. In other words, we have to assume that whatever information the author presents as evidence is, in fact, true, even when the evidence includes arguable statements. We can question the validity of the argument by evaluating whether the evidence alone is able to support the conclusion without making a large leap.

Remember that arguments are constructed to persuade you of the author’s idea. So, you should always get a firm grasp on the argument’s conclusion (whether or not you think it’s valid) and how the arguer structured the evidence to reach that conclusion. If you understand the conclusion and the reasoning behind it, you’ve won half the battle because most of the questions in Arguments revolve around the hows and whys of the arguer’s reasoning.

Let’s start with something fairly simple. Although this argument is simple, its structure is similar to that of many real LSAT arguments that you will see. Here it is:

Serena has to move to Kentucky. She lost the lease on her New York apartment, and her company is moving to Kentucky.

Okay, now what? We’ve got to make sure we understand the following things about this argument:

If we are able to identify the conclusion and premises, we are well on our way to being able to tackle an LSAT question about the argument. After reading the argument again, try to identify the following elements:

What’s the author’s conclusion? When looking for the author’s conclusion, try to figure out what the author is attempting to persuade us of. Ultimately, the author is trying to persuade us that Serena has to move to Kentucky. The rest of the information (about the lease and her company’s move) is given in support of that conclusion. Often, the author’s conclusion includes signal words such as thus, therefore, or so, or is a recommendation, a prediction, or an explanation of the evidence presented.

What are the author’s premises? So, why does the author think that Serena has to move to Kentucky? (1) She lost the lease on her apartment in New York, and (2) her company is relocating to Kentucky. Each of these is a premise in support of the conclusion. Now you know the author’s conclusion and the premises behind it. This should be the first step you take in analyzing almost every argument on the LSAT. After taking a look at this argument, however, you might be thinking that Serena may not have thought this whole thing through. After all, couldn’t she get another apartment in New York? And does she really have to stick with this company even though it’s moving halfway across the country? If you’re asking these kinds of questions, good! Hold onto those thoughts for another few minutes—we’ll come back to these questions soon.

What if I didn’t properly identify the author’s conclusion? Getting the author’s conclusion and understanding the reasoning behind it is crucial to tackling an argument effectively and performing whatever task the question demands of you. But let’s face it: Not every argument will be as simplistic as this one. It would be a good idea to have a technique to use when you aren’t sure of an argument’s conclusion. This technique is called the Why Test.

The Why Test should be applied to verify that you have found the author’s conclusion. Let’s take the previous example and see how it works. If you had said that the author’s conclusion was that she had lost her lease, the next step is to ask Why did the author lose her lease? Well, we have no idea why the author lost her lease. There is absolutely no evidence in the argument to answer that question. Therefore, we can’t have found the author’s conclusion.

Now, let’s say that you had chosen the fact that the author’s company was moving to Kentucky as the author’s conclusion. You would ask Why is the author’s company moving to Kentucky? Once again, we have no idea. But notice what happens when we use the Why Test on the author’s conclusion: that she has to move to Kentucky. Why does she have to move to Kentucky? Now we have some answers: because she lost the lease on her New York apartment, and because her company is moving to Kentucky. In this case, the Why Test works perfectly. You have identified the author’s conclusion.

Use the Why Test to determine whether you’ve properly identified the conclusion of the argument.

Now let’s take a look at another argument that deals with a slightly more complicated subject, one that’s closer to what you’ll see on the LSAT.

The mayor of the town of Shasta sent a letter to the townspeople instructing them to burn less wood. A few weeks after the letter was delivered, there was a noticeable decrease in the amount of wood the townspeople of Shasta were burning on a daily basis. Therefore, it is obvious that the letter was successful in helping the mayor achieve his goal.

Okay, now let’s identify the conclusion and premises in this argument.

What’s the author’s conclusion? The author is trying to persuade us that the letter was, in fact, the cause of the townspeople’s burning less wood. Notice the phrase “it is obvious that,” which indicates that a point is being made and that the point is debatable. Is there enough information preceding this statement to completely back it up? Can two short sentences persuade us that there is an “obvious” conclusion that we should come to when evaluating this information? Not if we’re thinking about the issue critically and thinking about some of the other possible causes for this effect.

What are the author’s premises? Let’s use the Why Test here. If we’ve chosen the right conclusion, asking “why” will give us the author’s premises. Why did the author conclude that the letter was successful in getting the townspeople of Shasta to burn less wood? The author’s premises are that the mayor sent a letter, and that the townspeople started burning less wood a few weeks later.

What’s missing? Remember how we said that you need to be critical and ask questions? Well, here’s your chance. Arguments on the LSAT are full of holes. Remember—it’s difficult to make a solid, airtight case in just three sentences. So let’s be skeptical and poke holes in this author’s reasoning.

What do you think about the author’s conclusion that the letter was responsible for helping the mayor achieve his goal? In evaluating the author’s argument, we’ll start with her premises—they’re the only facts that we have to go on. The mayor sends a letter to the townspeople, urging them to burn less wood, and a few weeks later, the townspeople start to burn less wood. (Remember that you have to accept these facts at face value. We have to accept that, for instance, there was in fact a noticeable decrease in the amount of wood being burned in Shasta.) Now, do we know for certain that the mayor’s letter is what caused the decline in burning? Couldn’t it have been something else? This author evidently doesn’t think so—she thinks it’s the letter and nothing else. We could come up with a hundred possible reasons that might explain why the residents of Shasta started to burn less wood, other than the mayor’s letter. (For example, the price of firewood could have doubled right before the decline in burning.) But by asking these questions, we know the important thing—that this author assumes that there wasn’t any other cause.

What is an assumption? An assumption, both in life and on the LSAT, is a leap of logic that we make to get from one piece of information to another. For instance, if you see a friend of yours wearing a yellow shirt and you conclude that your friend likes yellow, you would be making the following assumptions:

You get the point. You make these assumptions because you’ve seen a particular effect (in this case, your friend wearing a yellow shirt), and you think you’ve identified the proper cause (in this case, that your friend likes yellow and not that he is color-blind or needs to do some laundry). Then, whether or not it’s true, you assume a connection between the cause and the effect. You’ve made a leap of logic.

The assumptions made in the arguments on the LSAT are also leaps of logic. Sometimes, the logic is so simple that it looks as if the author has actually stated it but really hasn’t. The author’s assumption is never explicitly stated in the passage. By definition, it is always unstated.

In LSAT terms, an assumption is an unstated premise that is required in order to make an argument’s conclusion valid.

Let’s go back to the wood-burning argument. Here, we have an observed effect—the townspeople of Shasta burning less wood. We have a possible cause—the mayor’s letter. In LSAT-land, the arguer will often try to make a direct connection between these two pieces of information—in this case, that the letter caused the wood-burning decrease.

However, as we’ve seen from the above example, we’re also assuming the following:

Once again, you get the point. The author actually made many assumptions when she made the leap of logic from the letter being sent and people burning less wood on one hand, and the conclusion that the letter was successful on the other hand. They all revolve around two basic assumptions: that the letter could have caused the decline in firewood use and that no other factor was the cause of the decline.

You want to get to the answer choices, don’t you? Well, we will—soon. But what has been the point of the last several pages? To show you how to read the argument itself in a critical way. This will help you immensely in evaluating the answer choices because you will already understand the author’s conclusion and the premises on which it is based, and you’ll also have spotted any potential problems with the argument. This means that many times you’ll have the answer to the question in mind before you read any answer choices, and you can simply eliminate any that don’t match.

The reason we want you to stop and think before going to the answer choices is that the answer choices are not there to help you get a good score on the LSAT. Four of the answer choices are going to be wrong, and their purpose is to distract you from the “best” answer choice. True, many times this “best” choice will merely be the least sketchy of five sketchy answer choices. Nonetheless, the more work you put into analyzing the argument before reading the choices, the better your chance of eliminating the four distracters and choosing the “credited response.”

So why do we hammer this into you? Because you may or may not have had a lot of practice reading critically. You’re not simply reading for pleasure, or reading the newspaper or a menu at a restaurant—here, you’ve got to focus your attention on these short paragraphs. Read LSAT arguments critically, as if you’re reading a contract you’re about to sign. Don’t just casually glance over them so you can quickly get to the answer choices. You’ll end up spending more time with the answer choices trying to determine the credited response if you don’t have a solid understanding of the author’s conclusion and how she got there. The single most important thing to read extremely carefully is the author’s conclusion, whenever it is explicitly stated. Take the time to think critically about the argument, to break it down, and to be sure that you can paraphrase what the author is saying and articulate any flaws in her reasoning. Doing this will actually save you time by enabling you to evaluate the answer choices more quickly and efficiently.

We have developed a four-step process for working LSAT arguments. It is a very simple process that will keep you on task and increase your odds of success if you follow it for every argument that you do. Here are the steps.

Step 1: Assess the question

Step 2: Analyze the argument

Step 3: Act

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination

Now let’s look at these steps in more detail:

Step 1: Assess the question Sound familiar? This is one of your mantras. Reading the question first will tip you off about what you need to look for in the argument. Don’t waste time reading the argument before you know how you will need to evaluate it for that particular question. If you don’t know what your task is, you are unlikely to perform it effectively.

Step 2: Analyze the argument This is what we’ve been practicing for the last few pages. You’ve got to read the argument critically, looking for the author’s conclusion and the evidence used to support it. When the author’s conclusion is explicitly stated, mark it with a symbol that you use only for conclusions. If necessary, jot down short, simple paraphrases of the premises and any flaws you found in the argument.

To find flaws, you should keep your eyes open for any shifts in the author’s language or gaps in the argument. Remember that the author’s conclusion is reached using only the information on the page in front of you, so any gaps in the language or in the evidence indicate problems with the argument. You’ll always want to be sure that you’re reading critically and articulating the parts of the argument (both stated and unstated) in your own words. This will take a few extra seconds, but the investment will more than pay off by saving you loads of time in dealing with the answer choices.

Step 3: Act The particular strategy you’ll use to answer a given question will be determined by the type of question being asked (one more reason to start by focusing on the question task). Each question task will have different criteria for what constitutes an acceptable answer. You’ll want to think about that before going to the choices.

The test writers rely on the fact that the people who are taking the LSAT feel pressured to get through all the questions quickly. Many answer choices will seem appealing if you don’t have a clear idea of what you’re looking for before you start reading through them. The best way to keep yourself from falling into this trap is to predict what the right answer will say or do before you even look at the choices.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination We first mentioned Process of Elimination (POE) in Chapter 1. It’s a key to success on every section of the LSAT, especially Arguments and Reading Comprehension.

Almost every question in the Arguments section of the exam will fit into one of the following eleven categories: Main Point, Necessary Assumption, Sufficient Assumption, Weaken, Strengthen, Resolve/Explain, Inference, Reasoning, Flaw, Principle, and Parallel-the-Reasoning. Each of these types of questions has its own unique characteristics, which we’ll cover in the following pages. At the end of each question type you’ll find a chart summarizing the most important things to remember. The chart will be repeated in full at the end of the chapter for all eleven categories.

We’re finally going to give you an entire LSAT argument. First, we’ll give you the whole argument, and you can approach it by using the process we just outlined. Then, you can compare your results against ours. Finally, after each Argument “lesson,” we’ll explain some extra techniques that you’ll want to absorb. That way, by the end of Lesson 11, you’ll know everything you need to answer any Argument question the LSAT might throw at you. This first lesson is about Main Point questions. Good luck!

These questions are relatively rare, but because finding the main point is essential to answering most other Arguments questions correctly, it’s a good place to start.

1. Editorialist: A growing number of ecologists have begun to recommend lifting the ban on the hunting of leopards, which are not an endangered species, and on the international trade of leopard skins. Why, then, do I continue to support the protection of leopards? For the same reason that I oppose the hunting of people. Admittedly, there are far too many human beings on this planet to qualify us for inclusion on the list of endangered species. Still, I doubt the same ecologists endorsing the resumption of leopard hunting would use that fact to recommend the hunting of human beings.

Which of the following is the main point of the argument above?

(A) The ban on leopard hunting should not be lifted.

(B) Human beings are a species like any other animal and should be placed on the endangered species list.

(C) Hunting of animals, whether or not they are an endangered species, should not be permitted.

(D) Hunting of leopards, if they are not an endangered species, should not be regulated.

(E) Ecologists cannot be trusted when emotional issues such as hunting are involved.

Here’s How to Crack It

Step 1: Assess the question Did you remember to read the question before you started reading the argument? Here it is again:

Which of the following is the main point of the argument above?

This question asks for the main point, or conclusion, of the argument. Now you’re going to analyze the argument, and your goal is to identify the author’s conclusion.

Step 2: Analyze the argument Read the argument. Read it slowly enough that you maintain a critical stance and identify the author’s conclusion and premises. Here it is again:

Editorialist: A growing number of ecologists have begun to recommend lifting the ban on the hunting of leopards, which are not an endangered species, and on the international trade of leopard skins. Why, then, do I continue to support the protection of leopards? For the same reason that I oppose the hunting of people. Admittedly, there are far too many human beings on this planet to qualify us for inclusion on the list of endangered species. Still, I doubt the same ecologists endorsing the resumption of leopard hunting would use that fact to recommend the hunting of human beings.

The argument is about hunting leopards. Keep in mind that we need to find only the conclusion and premises when we’re working on a Main Point question. Finding assumptions won’t help us, so don’t waste precious time trying to figure them out. Here’s what we got for the author’s conclusion and premises:

If you had trouble identifying the conclusion, try thinking about why the author wrote this argument. The purpose of the argument is to disagree with someone else’s conclusion—the ecologists’ conclusion that the ban on leopard hunting should be lifted. Therefore, the conclusion is the opposite of the ecologists’ conclusion. The purpose of an argument—whether it is intended to interpret facts, solve a problem, or disagree with a position—is intimately connected to the main point.

Remember to use the Why Test to check the author’s conclusion if you’re not sure. Let’s go to Step 3.

Step 3: Act Now that you’ve broken down the argument and have all the pieces clear in your mind, it’s time to make sure that you approach the answer choices knowing what it is that you’ve been asked to find. If you’re not sure about exactly what you’re supposed to be looking for, you will be much more likely to fall for one of the appealing answer choices designed to distract you from the credited response. So, just to be sure you’re ready for the next step, we said that the author’s main point was that leopards should continue to be protected.

The credited response to a Main Point question will articulate the author’s conclusion.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Okay, now let’s look at each of the answer choices. Your goal is to eliminate four of the choices by crossing out anything that doesn’t match the paraphrase of the author’s main point. If any part of it doesn’t fit, get rid of it.

(A) The ban on leopard hunting should not be lifted.

Does this sound like the author’s conclusion? Yes. Let’s leave it.

(B) Human beings are a species like any other animal and should be placed on the endangered species list.

Is this the author’s conclusion? No, he never mentions anything about putting human beings on the endangered species list. In fact, he says that human beings are NOT an endangered species. Let’s cross it off.

(C) Hunting of animals, whether or not they are an endangered species, should not be permitted.

This looks pretty good, except that it’s too general. The argument is talking specifically about leopards. Let’s cross it off.

(D) Hunting of leopards, if they are not an endangered species, should not be regulated.

Look carefully at the wording of this answer: it is actually the opposite of the main point. The editorialist argues that it should be regulated, even though leopards are not endangered. Let’s cross it off.

(E) Ecologists cannot be trusted when emotional issues such as hunting are involved.

This choice has the same problem as (D). It doesn’t talk about leopards at all, so once again it is not relevant. It’s also a bit extreme given the tone of the passage. Let’s cross it off. Well, it looks like you’ve got (A), the right answer here. Nice job!

Let’s go into a bit more depth with Process of Elimination. Answer choices (B), (C), (D), and (E) above all presented us with specific reasons for crossing them off. Following are ways in which you can analyze answer choices to see if you can eliminate them.

LSAT arguments have very specific limits; the author of an argument stays within the argument’s scope in reaching his conclusion. Anything else is not relevant. When you read an argument, you must pretend that you know only what is written on the page in front of you. Never assume anything else. So, any answer choice that is outside the scope of the argument can be eliminated. We did this for answer choices (B), (D), and (E) in the last example. Many times, answer choices will be so general that they are no longer relevant; we eliminated choice (C) for this reason. Arguments are usually about specific things—such as leopards—as opposed to just “animals.” The ultimate deciding factor about what is or is not within the scope of the argument is the exact wording of the conclusion.

Pay attention to the wording of the answer choices. For some question types (most notably Main Point and Inference), extreme, absolute language (never, must, exactly, cannot, always, only) tends to be wrong, and choices with extreme language can usually be eliminated. Keep in mind, however, that an argument that uses strong language can support an equally strong answer choice. Extreme language is another reason that we eliminated choice (E). You should always note extreme language anywhere—in the passage, the question, or the answer choices—as it will frequently play an important role.

Make sure that you are not choosing the exact opposite of the viewpoint asked for. Many times, this type of answer choice will look good because it’s talking about the same subject matter as the correct answer; the trouble is that this answer choice presents an opposite viewpoint. For some question types, such as Weaken, Strengthen, and Main Point, one of the answer choices will almost always be an “opposite.”

Check out the chart below for some quick tips on Main Point questions. The left column of the chart shows some of the ways in which the LSAT folks will ask you to find the conclusion. The right column is a brief summary of the techniques you should use when approaching Main Point questions.

Understanding the purpose of an argument can help lead you to the main point.

Assumption questions ask you to pick the choice that fills a gap in the author’s reasoning. A necessary assumption is something that the argument relies on but doesn’t state—something that needs to be true in order for the argument to work.

2. Analyst: Television news programs have always discussed important social issues. While in the past such programs were primarily geared toward educating citizens about these issues, today the main focus in television news is on attracting larger audiences. Television viewers tend to prefer news programs that present views in agreement with their own. There can be little doubt, then, that at least some contemporary television news programs harm society by providing incomplete coverage of important social issues.

Which one of the following is an assumption on which the analyst’s argument relies?

(A) At least some citizens of earlier eras were better educated about important social issues than are any viewers of contemporary television news programs.

(B) It is to society’s advantage that citizens be exposed to some views of important social issues that they may not prefer to see presented in television news programs.

(C) Television news coverage of an important social issue is incomplete unless it devotes equal time to each widely held view about that issue.

(D) The factual accuracy of television news coverage of an important social issue is not the most important criterion to use in assessing its value to society.

(E) Television viewers exhibit the greatest preference for news programs that present only those views of important issues with which they agree.

Here’s How to Crack It

Step 1: Assess the question Here’s the question again:

Which one of the following is an assumption on which the analyst’s argument relies?

It includes not only the word assumption, but also the word relies. This sort of language—relies on, depends on, requires—is a sure sign of a Necessary Assumption question.

Step 2: Analyze the argument On a Necessary Assumption question, we analyze the argument by finding its conclusion and premises, as before. But there’s something else we need to do. If possible, we need to find what’s wrong with the argument before we go to the answer choices. Do this by maintaining a skeptical attitude and looking for differences in wording. Here’s the argument again:

Analyst: Television news programs have always discussed important social issues. While in the past such programs were primarily geared toward educating citizens about these issues, today the main focus in television news is on attracting larger audiences. Television viewers tend to prefer news programs that present views in agreement with their own. There can be little doubt, then, that at least some contemporary television news programs harm society by providing incomplete coverage of important social issues.

One thing to look for in any argument like this is a new idea or a judgment call in the conclusion. On the LSAT, we’re always looking for whether the conclusion is properly drawn from the premises. If an important idea is missing from the premises, then that’s a serious problem with the argument. Here’s what we came up with:

Where did we get our assumptions? By noticing that the key ideas “incomplete coverage” and “harm [to] society” are included in our conclusion but not anywhere else in the argument.

You may be looking at one or the other of the assumptions we found and asking, “Didn’t they basically say that?” For example, look at our assumption hinging on the idea of “incomplete coverage.” In the premises, we’re told that news programs are looking to attract audiences and that audiences tend to prefer to hear views they agree with. Doesn’t that tell you for certain that the coverage is going to be incomplete?

Not really. In fact, when you look at it closely, it is a pretty big jump. All we know is that people like to hear their own views covered; does that really mean that they don’t want to see other views?

When you’re looking for the problems in an argument, it’s important not to give the argument the benefit of the doubt. Be skeptical, and examine the language of the conclusion very closely.

Step 3: Act Once you’ve found one or more problems with the argument, you’re almost ready to go. Realize that an assumption will not only help the argument, usually by fixing one of the problems you’ve identified, but it will also be essential to the argument. Here, we want something that supplies the idea of “incomplete coverage” or “harm [to] society” or, if we get lucky, both.

The credited response to a Necessary Assumption question will be a statement that is essential for the argument’s conclusion to be valid.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Let’s take the choices one at a time:

(A) At least some citizens of earlier eras were better educated about important social issues than are any viewers of contemporary television news programs.

This one seems to go along with the argument more or less, but notice how demanding this choice is. It says that, in the past, there were citizens who were more educated about important social issues than are any citizens now. That language is too strong. An assumption is something the argument needs, but we don’t want to pick a choice that’s more than what the argument needs. This falls in that category; let’s eliminate it.

(B) It is to society’s advantage that citizens be exposed to some views of important social issues that they may not prefer to see presented in television news programs.

One thing you can say about this choice is that it certainly doesn’t have the problem we saw in choice (A). Notice how careful the language here is. We get “to society’s advantage” (rather than “essential,” say); “some views” (rather than all of them); “may not prefer to see” (instead of “wish to avoid,” for example). Choice (B) also seems to go along with the argument. We can associate “society’s advantage” with the opposite of “harm” in the conclusion, and the idea of what viewers prefer to see comes right out of the premises. Let’s keep this one for now.

(C) Television news coverage of an important social issue is incomplete unless it devotes equal time to each widely held view about that issue.

This one sounds good until we realize how demanding it is. Does every news program have to devote absolutely equal time to every widely held view? The argument doesn’t need anything quite this strong. Let’s eliminate it.

(D) The factual accuracy of television news coverage of an important social issue is not the most important criterion to use in assessing its value to society.

Initially you might eliminate this one out of hand because it mentions “factual accuracy,” an idea not contained in the argument. We need to restrain ourselves for a moment, however. After all, if the argument’s primary concern were to point out the factor that is most important in evaluating news coverage, then this answer choice would be relevant, even if factual accuracy were not mentioned as such. In other words, the relevance of the choice is determined by what the argument is trying to do—its scope.

To determine the exact scope of the argument, look at the conclusion. Is the argument primarily concerned with saying that completeness is the most important factor is assessing news coverage? No. We can now be certain that this choice isn’t relevant and eliminate it.

(E) Television viewers exhibit the greatest preference for news programs that present only those views of important issues with which they agree.

You probably recognize this as a much stronger rendition of one of the argument’s premises. The word “only” as it is used here makes this choice so demanding that we should definitely eliminate it. Not only that, but we won’t generally find assumptions that are simply one-offs of a premise. The premises are facts already; most of the time, they don’t need any further support.

We’re left with (B), which is the answer here. Notice that choice (B) isn’t exactly what we came up with when we analyzed the argument; this is quite common on the LSAT. But we recognized that it related to a part of the conclusion that was problematic (the idea of “harm”), that it connected this idea back to the premises, and that it had the proper strength for this argument. Knowing where the potential problems in an argument are will help you recognize assumptions, even when they don’t exactly match the assumptions you expected to find.

Finding an assumption can be one of the most difficult things to do on the LSAT. But as we said before, sometimes looking for a language shift between the conclusion and the premises will help you spot it. Let’s look at an example of how this works. Consider the following argument:

Ronald Reagan ate too many jelly beans. Therefore, he was a bad president.

All right. You probably already think you know the assumption here; it’s pretty obvious. After all, how do you get from “too many jelly beans” to “bad president”? This argument just doesn’t make any sense, and the reason it doesn’t make sense is that there’s no connection between eating a lot of jelly beans and being a bad president.

But now consider this argument:

Ronald Reagan was responsible for creating a huge national debt. Therefore, he was a bad president.

Suppose you were a staunch Reagan supporter, and someone came up to you and made this argument. How would you respond? You’d probably say that the debt wasn’t his fault, that it was caused by Congress, Jimmy Carter, or the policies of a previous administration. You would attack the premise of the argument rather than its assumption. But why? Well, because the assumption here might seem reasonable to you. Consider the parts of the argument:

Conclusion: Ronald Reagan was a bad president.

Premise: Ronald Reagan was responsible for creating a huge debt.

As far as the LSAT is concerned, the assumption of this argument works in basically the same way as the assumption of the first version. Initially, we saw that the link from “ate too many jelly beans” to “bad president” was what the argument was missing. Here, what’s missing is the link from “huge national debt” to “bad president.” In the first case, the assumption stands out more because it seems ridiculous. It’s important to understand, though, that our real-world beliefs about whether or not an assumption is good play no role in analyzing arguments on the LSAT. Even if you consider it reasonable to associate huge national debt with being a bad president, this is still the connection the argument needs to establish in order for its conclusion to be properly drawn. Of course, assumptions that you consider reasonable are more difficult to spot, because unless you pay very close attention, you may not even realize they’re there.

It’s also important to understand, as you analyze arguments, that there is a big difference between an assumption of the argument and its conclusion. The conclusions of the two arguments above are the same: “[Ronald Reagan] was a bad president.” The conclusion of an argument is the single, well-defined thing that the author wants us to believe. Once you start thinking about why we should believe it, you’re moving past the conclusion into the reasoning of the argument. In these two arguments, the premises are different; because assumptions most often connect one or more premises to the conclusion, the assumptions of these two arguments are different, even though their conclusions are the same.

Finally, don’t make your life too difficult when you’re analyzing an argument to find its assumptions. You don’t need to write LSAT answer choices in order to have a good sense of what’s wrong with an argument. In the national debt argument above, for example, it’s enough to know what the argument does wrong: that it’s missing the connection from “huge debt” to “bad president.” Knowing that this is the link your answer will need to supply is plenty to get you ready to evaluate the answer choices.

We said before that a necessary assumption is something the argument needs in order for its conclusion to follow from the premises. We’ve described a number of ways to find necessary assumptions for yourself, but when you’re doing Process of Elimination on Necessary Assumption questions, there is something you can do that will tell you for certain whether a particular fact is essential to an argument.

We call it the Negation Test.

Negate the answer choice to see whether the conclusion remains intact. If the conclusion falls apart, then the choice is a valid assumption and thus the credited response.

Because a necessary assumption is required by the argument, all you have to do is suppose the choice you’re looking at is untrue. If the choice is essential to the argument, then the argument should no longer work without it. It takes a bit of practice, but it’s the strongest elimination technique there is for Necessary Assumption questions.

Let’s try it with two choices from our first example—the one about television news programs. If you need to, flip back to review the conclusion and premises of the argument. Then take a look at the answer we ended up choosing:

(B) It is to society’s advantage that citizens be exposed to some views of important social issues that they may not prefer to see presented in television news programs.

To negate a choice, often all you have to do is negate the main verb. In this case, here’s how it looks:

It is NOT to society’s advantage that citizens be exposed to some views of important social issues that they may not prefer to see presented in television news programs.

What does this mean? It doesn’t help society for people to be exposed to views different from their own. Supposing that this is true, how much sense does the argument make? Not much. After all, the whole point was that not getting a range of views is harmful to society.

Notice that the same method can be used to eliminate answers as well as confirm them. Take this other choice from the same question:

(D) The factual accuracy of television news coverage of an important social issue is not the most important criterion to use in assessing its value to society.

Negated, it looks like this:

The factual accuracy of television news coverage of an important social issue IS the most important criterion to use in assessing its value to society.

Even if this is true, does that make the conclusion wrong? Not really. Even if accuracy is the most important criterion to use, that doesn’t mean that other criteria are meaningless. The argument is concerned with proving that a particular aspect of news coverage is doing harm. It’s quite possible that the statement above and the argument’s conclusion are both right. In other words, negating this choice has no real effect on the argument, so it can’t be a necessary assumption.

Certainly the Negation Test can be difficult to do in some cases. Negating (C) on the same question, for example, is quite a challenge. For this reason, the Negation Test shouldn’t be a first-line elimination method for you. It can be quite helpful, however, in a case when you’re down to two answer choices that both seem appealing, or as a final check before you settle on your answer. And if you make the effort to practice this technique on Necessary Assumption questions, you’ll find that it gets easier to do.

Now let’s try another Necessary Assumption question.

3. Car owner: My mechanic believes that my car’s wheels must be out of alignment because the fact that the tires are underinflated cannot by itself account for the steering problems I’ve been having for the past several months. But because my gas mileage has been steady during the same time period, the alignment of my car’s wheels must be normal.

Which one of the following is an assumption required by the car owner’s argument?

(A) A drop in gas mileage occurs only if a car’s wheels are out of alignment.

(B) Underinflated tires can cause a car’s gas mileage to drop.

(C) A car’s gas mileage varies less under test conditions than it does on the open road.

(D) Misaligned wheels can sometimes cause a change in a car’s gas mileage.

(E) Underinflated tires and misaligned wheels cannot both cause steering problems.

Step 1: Assess the question As always, read the question first. Here it is again:

Which one of the following is an assumption required by the car owner’s argument?

The words assumption and required tell you that this is a Necessary Assumption question. You know that you’ll need to identify the conclusion and the premises and that you’ll need to think about the gap in the author’s logic.

Step 2: Analyze the argument Read the argument. Identify the important components. Here it is again.

Car owner: My mechanic believes that my car’s wheels must be out of alignment because the fact that the tires are underinflated cannot by itself account for the steering problems I’ve been having for the past several months. But because my gas mileage has been steady during the same time period, the alignment of my car’s wheels must be normal.

One common way that you’ll see the conclusion phrased on the LSAT is as the opposite of someone else’s opinion. (We saw this on the leopard question in the previous section.) We’re told that the mechanic believes that the car’s wheels are out of alignment. Notice, however, the word but at the beginning of the second sentence. This tells us that the author is about to disagree with the mechanic, and you can quickly identify the conclusion as the last line of the argument: “the alignment of my car’s wheels must be normal.”

What information is given to support this? Well, the author has been having steering problems, underinflated tires by themselves can’t be the reason for those problems, and his gas mileage has been holding steady. If you notice that none of these premises mentions wheel alignment, you’re on your way to finding the right answer.

Step 3: Act All we know for sure is that the right answer will have to link the conclusion and the premise together somehow. Let’s use that as our first POE criterion and move to the answer choices.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Here we go:

(A) A drop in gas mileage occurs only if a car’s wheels are out of alignment.

Does this suggest a link between alignment and mileage? Yes, it does. We’ll hold on to it.

(B) Underinflated tires can cause a car’s gas mileage to drop.

Does this suggest a link between alignment and mileage? No, it doesn’t. In fact, alignment isn’t mentioned at all. This links the car owner’s premise with the premise from the mechanic’s argument. Let’s cross it off.

(C) A car’s gas mileage varies less under test conditions than it does on the open road.

Test conditions and the open road seem completely irrelevant, and this choice doesn’t mention the conclusion at all. Let’s cross it off.

(D) Misaligned wheels can sometimes cause a change in a car’s gas mileage.

This seems a lot like (A). It mentions both the premise and the conclusion. We’ll hold on to it.

(E) Underinflated tires and misaligned wheels cannot both cause steering problems.

This mentions the main topic of the argument, steering problems, as well as the misaligned wheels from the conclusion. Let’s keep it, just in case.

This will happen from time to time. It looks like we’ll have to do some more thinking. Always reread the conclusion and the question before you compare the answer choices. Here they are again:

Author’s conclusion: The car’s wheels aren’t misaligned.

Question: Which one of the following is an assumption required by the car owner’s argument?

Let’s start with (E), only because it’s unlike the other two. Don’t forget about negating answer choices—it’s a useful technique. If you negate (E), it will read, “Underinflated tires and misaligned wheels can both cause steering problems.” Remember that when you negate the correct answer, it should make the argument fall apart. Just because misaligned wheels (and underinflated tires) can both cause steering problems doesn’t mean that they are absolutely causing the steering problems in this case. And it doesn’t mention the issue of mileage, which is a crucial piece of the car owner’s argument. If anything, this choice serves to address the mechanic’s conclusion, but we want to focus on the car owner’s conclusion. Let’s cross it off.

How about (A)? Let’s look at it more closely:

(A) A drop in gas mileage occurs only if a car’s wheels are out of alignment.

This says that if my mileage drops, then I know for sure that my wheels aren’t aligned (because according to the answer choice, misaligned wheels are necessary for a drop in gas mileage to occur). Does this say anything about what I know if I don’t get a drop in gas mileage? No, it doesn’t. Because we care only about what’s true if I don’t get a drop in gas mileage (because that’s the premise in the argument), we can eliminate this choice.

That leaves us with (D):

(D) Misaligned wheels can sometimes cause a change in a car’s gas mileage.

Try negating that one: Misaligned wheels can never cause a car’s gas mileage to change. If it were true that misaligned wheels could never be the cause of a change in gas mileage, then how could the author cite steady gas mileage as proof that the wheels were aligned? He couldn’t. Remember that we originally said the assumption had to relate mileage to alignment; by negating this choice, we effectively say that there is no relationship between the two. Having steady gas mileage, then, would not tell us anything about the alignment of the car’s wheels. The negated version of answer choice (D) destroys the argument and is therefore the credited response to the argument.

We’ve just covered a ton of information regarding Necessary Assumption questions. Remember that a necessary assumption is something that the argument needs in order for its conclusion to be correctly reached. For that reason, any answer you pick on a Necessary Assumption question should, at a bare minimum, help the author’s argument. If you negate the right answer on a Necessary Assumption question, what you’ll find is that the argument either disintegrates entirely, or the connection between the premises and the conclusion is severed. Finally, watch out for choices that are too strongly worded or overly specific; these types of choices may seem right to you at first, but they frequently go too far or insist upon too much.

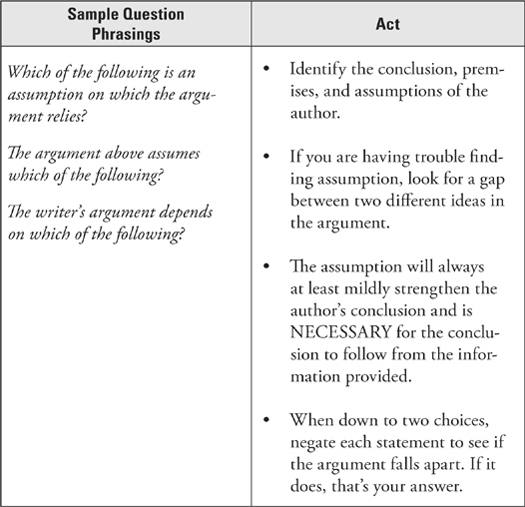

Below is a chart that summarizes Necessary Assumption questions.

Sufficient Assumption questions have a lot in common with the Necessary Assumption questions you just looked at it. Both ask you to identify the missing gap in the author’s reasoning.

Sufficient Assumption questions, however, differ in that they aren’t asking you for an assumption that is required by the argument; rather, they simply are asking you for an assumption, that, if true, would allow for the conclusion to follow.

Because of this, Sufficient Assumption questions will often have credited answers that are stronger, broader, or more far-reaching than credited responses on Necessary Assumption questions. Let’s revisit Ronald Reagan to see why:

Ronald Reagan ate too many jelly beans. Therefore, he was a bad president.

Now, when we originally analyzed this argument, we identified the huge assumption that the argument makes: namely, that eating a certain quantity of jelly beans reflects in some way upon one’s skill at being leader of the free world.

This is a necessary assumption; if eating jelly beans didn’t reflect at least somewhat upon Reagan’s ability to be president, then this argument has no hope of proving its conclusion.

But what if the LSAT was willing to grant to you a premise that said that the number of jelly beans one eats is the only indicator of one’s ability to preside? Would that do it for the argument? We don’t need jelly beans to be the only factor, but if they were, would the conclusion follow logically? You bet it would.

Try the Negation Test though. If eating jelly beans wasn’t the only indicator of Ronald Reagan’s presidential prowess, would the argument fall to pieces? Not necessarily—we needed to know only that jelly beans have something to do with his abilities as a president.

This is what separates Sufficient Assumption questions from Necessary Assumption questions. The credited responses can be more extreme, and the Negation Test can’t help us.

Let’s look at an example closer to what you’ll see on the LSAT.

4. Politician: The interstate highway system in Case County connects its three cities. The interstate connecting Bryantsville with Carptown has three more lanes than the interstate connecting Bryantsville with Alephtown. So clearly, Bryantsville has stronger economic ties to Carptown than it does to Alephtown.

The politician’s argument follows logically if which one of the following is assumed?

(A) The roads connecting Bryantsville with Alephtown and Carptown are more developed than the roads connecting Bryantsville to any other town.

(B) Bryantsville doesn’t have stronger economic ties to some city other than Carptown.

(C) Some other city doesn’t have its strongest economic ties with Bryantsville.

(D) The interstate system in Case County is one of the best in the world.

(E) The number of lanes on an interstate connecting two cities is directly proportional to the degree of economic development between them.

Here’s How to Crack It

Step 1: Assess the question What makes this a Sufficient Assumption question? Here it is:

The politician’s argument follows logically if which one of the following is assumed?

The word assumed can pretty reliably tell us that we’re looking at an assumption question of some sort. Notice, however, that the test writers aren’t asking us for an assumption on which the argument relies or depends, as they did with Necessary Assumption questions. Rather, they’re giving us a hypothetical: If we plug this answer choice into the argument as a missing premise, would it be enough to get us to the conclusion?

Step 2: Analyze the argument Just as we did with Necessary Assumption questions, we’ll start off by looking for the argument’s conclusion and premises. Here’s the argument one more time:

Politician: The interstate highway system in Case County connects its three cities. The interstate connecting Bryantsville with Carptown has three more lanes than the interstate connecting Bryantsville with Alephtown. So clearly, Bryantsville has stronger economic ties to Carptown than it does to Alephtown.

And here’s what our analysis reveals:

Step 3: Act The good thing about Sufficient Assumption questions is that the correct responses don’t introduce new information. Instead, they make the connection between the premises and the conclusion as strong as possible. So go ahead; make a wish for the answer choice that would do the best job of sealing the deal on the conclusion, and you’re likely to find something similar in the answer choices.

In this case, there is a language shift between the number of lanes (discussed in the premises) and the strength of economic ties (discussed in the conclusion). You’d love to see an answer choice telling you that you can judge the strength of economic ties between two cities by the amount of lanes on the interstate between them. Keep your wish in mind as you go to the answer choices.

The credited response to a Sufficient Assumption question will make an explicit connection between the premises and the conclusion—strong enough to prove the conclusion.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Now we go to the answer choices, keeping in mind that our correct answer choice must prove the conclusion and will not bring in new information. Let’s take a look:

(A) The roads connecting Bryantsville with Alephtown and Carptown are more developed than the roads connecting Bryantsville to any other town.

This would not tell us anything about the economic ties between the two cities. Also, this answer choice requires additional information about the roads connecting Bryantsville to towns other than Alephtown and Carptown, so this is a no-go.

(B) Bryantsville doesn’t have stronger economic ties to some city other than Carptown.

This is not relevant to the argument, whose scope is limited to the comparative economic ties of Bryantsville with Carptown and Bryantsville with Alephtown.

(C) Some other city doesn’t have its strongest economic ties with Bryantsville.

Like choice (B), this is not relevant to the argument. It brings in new information we simply don’t care about.

(D) The interstate system in Case County is one of the best in the world.

Again, this does not tell us anything about how the roads relate to economic ties.

(E) The number of lanes on an interstate connecting two cities is directly proportional to the degree of economic development between them.

Aha! This is exactly what we need. If we add this to the premises, the conclusion clearly follows directly from the premises. It is the missing link, shoring up the gap between the language of the premises and the language of the conclusion.

Sufficient Assumption questions always bring up ideas in the conclusion that are not discussed in the premises. The credited response will make an explicit connection between the two, positively sealing the deal on the conclusion. On more difficult Sufficient Assumption questions, you may see conditional statements or answer choices that seem very similar. Focus on proving the conclusion and making sure the answer choice goes in the right direction, eliminating answer choices that bring in new information that doesn’t get you any closer to the conclusion. Look for the strongest answer.

Weaken questions ask you to identify a fact that would work against the argument. Sometimes the answer you pick will directly contradict the conclusion; at other times, it will merely sever the connection between the premises and the conclusion, destroying the argument’s reasoning. Either way, the right answer will exploit a gap in the argument.

5. Goiter is a disease of the thyroid gland that can be caused by an iodine deficiency. Although goiter was once relatively common in the United States, especially among the poor, it has become rare, due in part to the wide use of iodized table salt. Thus, although health professionals often counsel patients to avoid salt, it is clear that residents of the United States must consume at least some table salt in order to assure good health.

Which one of the following, if true, would most seriously undermine the argument?

(A) Excess salt consumption is a contributing factor in hypertension, which can lead to heart attack and stroke.

(B) Factors other than the prevention of goiter are also crucial to maintaining good health.

(C) Historically, goiter due to iodine deficiency was found only in people who consumed low quantities of iodine-rich foods such as fish and dairy products, which are now as easily available to all United States residents as iodized salt.

(D) Goiter was only widespread in the United States before it was known that an iodine deficiency was responsible for the disorder.

(E) It is nearly impossible for residents of the United States to avoid consuming at least some iodized salt, because it is almost universally used in processed, packaged, and prepared foods.

Here’s How to Crack It

Step 1: Assess the question Always go to the question first. Here it is:

Which one of the following, if true, would most seriously undermine the argument?

The word weaken or one of its synonyms—undermine, call into question, cast doubt upon—is a clear indication of the kind of question we’re facing here.

Step 2: Analyze the argument As usual, we’ll start off by finding and marking the conclusion and the premises. And because the right answer on a Weaken question will often attack a conspicuous problem with the argument’s reasoning, we also need to look for those problems before we proceed. Here’s the argument again:

Goiter is a disease of the thyroid gland that can be caused by an iodine deficiency. Although goiter was once relatively common in the United States, especially among the poor, it has become rare due in part to the wide use of iodized table salt. Thus, although health professionals often counsel patients to avoid salt, it is clear that residents of the United States must consume at least some table salt in order to assure good health.

And here’s what we came up with from our analysis:

This second assumption—that avoiding goiter is necessary for maintaining good health—might fall under the heading of a “commonsense” assumption, to borrow a word from the directions on this section. That is, because goiter is described in the argument as “a disease,” the link between that and health seems pretty solid. Our job when we work these questions is to identify possible problems, not to write the answer choices. When you notice a difference in language or a questionable interpretation of the facts, all you need to do is note it and realize that it might be significant.

Step 3: Act On a Weaken question, you won’t usually be able to predict the exact content of the right answer. You know what’s wrong with the argument, and the chances are that the right answer will exploit that flaw somehow. In this case, we anticipate that the answer choice we want will tell us how a U.S. resident might avoid goiter without having to consume any table salt.

Remember that the premises must be accepted as true. The credited response to a Weaken question will give a reason why the author’s conclusion might not be true, despite the true premises offered in support of the conclusion.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Keep your eyes on the prize; remember that what we want are things that work against the conclusion.

(A) Excess salt consumption is a contributing factor in hypertension, which can lead to heart attack and stroke.

Broadly speaking, this works against the conclusion by showing a way salt consumption might be inimical to good health. Let’s keep it for now.

(B) Factors other than the prevention of goiter are also crucial to maintaining good health.

This does pertain to the new idea “good health” in the conclusion, and it does seem to be going against the argument in some way. But is it really an effective attack? Check the conclusion. It says that consuming table salt (to prevent goiter) is something that you have to do, but it never claims this is the only thing you have to do. The only real impact this choice has is to confirm that avoiding goiter really is necessary to good health. This certainly doesn’t weaken, so we should eliminate it.

(C) Historically, goiter due to iodine deficiency was found only in people who consumed low quantities of iodine-rich foods such as fish and dairy products, which are now as easily available to all United States residents as iodized salt.

You might initially be turned off by the mention of history, but what is this choice really telling us? That there’s something else that is evidently effective at preventing goiter, and that this thing is just as widely available in the United States now as iodized salt is. That works against the conclusion, so we’ll keep it.

(D) Goiter was only widespread in the United States before it was known that an iodine deficiency was responsible for the disorder.

This is nice to know, but it’s difficult to see what effect this has on our conclusion about salt. Eliminate it.

(E) It is nearly impossible for residents of the United States to avoid consuming at least some iodized salt, because it is almost universally used in processed, packaged, and prepared foods.

Even if this is true, it doesn’t work against our conclusion. Whether it’s possible to avoid iodized salt or not really has nothing to do with the question of whether we need to consume iodized salt to remain healthy. Eliminate this one.

We have two choices left, a circumstance you’ll frequently encounter on the LSAT. How do you make up your mind?

On Weaken questions, our task is to find the strongest attack on the conclusion. There might be more than one answer that seems to be working against the overall reasoning, so we need to go back, make sure we understand the conclusion fully, and then look for the one that has the most direct impact on it.

Things that can be important here are quantity words and the overall strength of language involved. Generally speaking, because we want a clear attack, we’ll often see strong wording in the right answer. More important, we want to make sure that the answer we pick hits the conclusion squarely and doesn’t just strike a glancing blow somewhere off to the side. Let’s try comparing the impact of our two remaining choices in the previous example.

As a reminder, here’s the argument’s conclusion:

Residents of the United States must consume at least some table salt in order to assure good health.

And here’s choice (A):

Excess salt consumption is a contributing factor in hypertension, which can lead to heart attack and stroke.

Does this really hurt the conclusion? Not once we focus our attention on the strength of language involved. The argument states only the relatively minimal conclusion that you need to consume “at least some table salt.” Choice (A) talks about “excessive salt consumption.” Are they really the same thing? No.

By contrast, here’s choice (C):

Historically, goiter due to iodine deficiency was found only in people who consumed low quantities of iodine-rich foods such as fish and dairy products, which are now as easily available to all United States residents as iodized salt.

Notice the strength of “only” here. It seems innocuous, but it’s plenty to let us know that the lack of these iodine-rich foods was the real culprit in causing goiter related to iodine deficiencies. Now, though, these foods are “as easily available to all United States residents as iodized salt.” That is, there’s no benefit table salt offers—either in terms of efficacy or availability—that isn’t also offered by these other foods. This is a direct attack and, thus, is the choice we want to pick.

When more than one answer choice seems to do the job, make sure you go back to the conclusion and look for the choice that attacks it most directly.

There are a few classic Argument types that show up repeatedly on the LSAT. It’s helpful to become familiar with these so that you can more easily recognize the assumptions that are built into them.

“Causal” is shorthand for cause and effect. A causal argument links an observed effect with a possible cause for that effect. A causal argument also assumes that there was no other cause for the observed effect.

Take a look at this simple causal argument:

Every time I walk my dog, it rains. Therefore, walking my dog must be the cause of the rain.

Absurd, right? However, this is classic causality. We see the observed effect (it’s raining), we see a possible cause (walking the dog), and then the author connects the two by saying that walking his dog caused the rain, thereby implying that nothing else caused it. So why are causal assumptions so popular on the LSAT? Because people often confuse correlation with causality. If we use shorthand for the possible cause (A) and the effect (B), we can see what the common assumptions are when working with a causal argument:

Of course, causal arguments on the LSAT won’t be that absurd, but they’ll have the same basic structure. The great thing about being able to identify causal arguments is that once you know where their potential weaknesses are, it becomes much easier to identify the credited response for Weaken, Strengthen, and both types of questions.

Another popular type of Argument on the LSAT is the sampling or statistical argument. This assumes that a given statistic or sample is sufficient to justify a given conclusion or that an individual is representative of a group. Here’s an example:

In a group of 50 college students chosen from among those who receive athletic scholarships, more than 80 percent said in a recent survey that they read magazines daily. So it follows that advertisers who wish to reach a college-age audience should place ads in magazines.

What is being assumed here? That the students who were chosen are a representative sample of the college-age population. In this case, the students who are used as evidence are (a) college students and (b) recipients of athletic scholarships. That’s a small subset of the population. The population the advertisers wish to reach is a “college-age” audience, a much broader group. In this case, there may be two ways in which the sample fails to represent the larger group. Those surveyed are college students while the target audience is “college-age.” Can we assume that college students are representative of everyone who is college-age? If not, the argument has a problem. Further, even if we could accept college students as representative of college-age people in general, we would still have to believe that those college students who receive athletic scholarships are representative of all college students.

Whenever you see something about a group being used as evidence to conclude something about a larger population, remember that the argument’s potential weakness is that the sample is skewed.

A third type of common Argument type on the LSAT is argument by analogy. In this case the author assumes that a given group, idea, or action is logically similar to another group, idea, or action. Read the argument below.

Overcrowding of rats in laboratory experiments has been shown to lead to aberrant behavior. So it follows that if people are placed in overcrowded situations, they will begin to exhibit aberrant behavior as well.

What is the potential weakness here? That, with respect to the conditions of the argument—here, overcrowding and aberrant behavior—people and rats might not be analogous. To weaken such an argument, you would need to find a relevant way in which the two things being compared are dissimilar.

6. A study was conducted to determine what impact, if any, last year’s aggressive shark-fishing campaign had on the local seal population. Since the campaign began, the seal population has increased by 25 percent. Thus, the removal of large numbers of sharks from the ecosystem allowed the population of seals to increase.

Which of the following, if true, most seriously weakens the argument?

(A) A previously unidentified virus was responsible for the deaths of a large number of sharks in the same area in the last year.

(B) Sharks prey on many species of fish as well as seals.

(C) Excess bait used to lure the sharks provided the seals with a plentiful source of nutrition.

(D) The shark-fishing campaign included many different shark species.

(E) Reducing the shark population has a number of negative side effects on the ecosystem as a whole.

Here’s How to Crack It

Step 1: Assess the question This question might be familiar. Here it is again:

Which of the following, if true, most seriously weakens the argument?

Clearly, we’re out to weaken the argument.

Step 2: Analyze the argument Read the argument carefully. Identify the conclusion, the premises the author offers as evidence, and any assumptions he makes. Here’s the body of the argument:

A study was conducted to determine what impact, if any, last year’s aggressive shark-fishing campaign had on the local seal population. Since the campaign began, the seal population has increased by 25 percent. Thus, the removal of large numbers of sharks from the ecosystem allowed the population of seals to increase.

Did you recognize this as a causal argument? The conclusion suggests that the decrease in the shark population caused the increase in the seal population. What evidence did the author use to back this up? Nothing more than the increase in population itself since the time the fishing began. This is a classic causal argument. The author wants you to believe that just because two things happened at the same time, one of them must have caused the other.

What are the automatic assumptions that an author makes in a causal argument? One is that the cause-and-effect relationship isn’t reversed. In this case, that isn’t very helpful. How could an increase in the seal population cause the shark population to go down? The second assumption is that nothing else caused the observed effect. In this case, that means the author is assuming that nothing else besides the decrease in the shark population caused the increase in the seal population.

Let’s summarize:

Step 3: Act Okay. We’re looking for an alternate cause, and there could be many of them. In fact, it’s highly unlikely that we’ll be able to predict the “right” one so we shouldn’t even bother with predictions. In general, we’re looking for a choice that suggests another reason the seal population increased.

Step 4: Use Process of Elimination Be careful here. Because we’re looking for an alternate cause, the right answer might seem out of scope because it introduces new information that doesn’t necessarily refer to something in the body of the argument. Let’s look at them one by one:

(A) A previously unidentified virus was responsible for the deaths of a large number of sharks in the same area in the last year.

This seems to give an alternate cause for the decrease in the number of sharks, not the increase in the number of seals. It’s not quite what we’re looking for, but let’s leave it in for now.

(B) Sharks prey on many species of fish as well as seals.

This is completely out of the scope of our argument, and it doesn’t give a reason the seal population may have increased other than the removal of the sharks. Let’s get rid of it.

(C) Excess bait used to lure the sharks provided the seals with a plentiful source of nutrition.