Chapter 2

City of Light

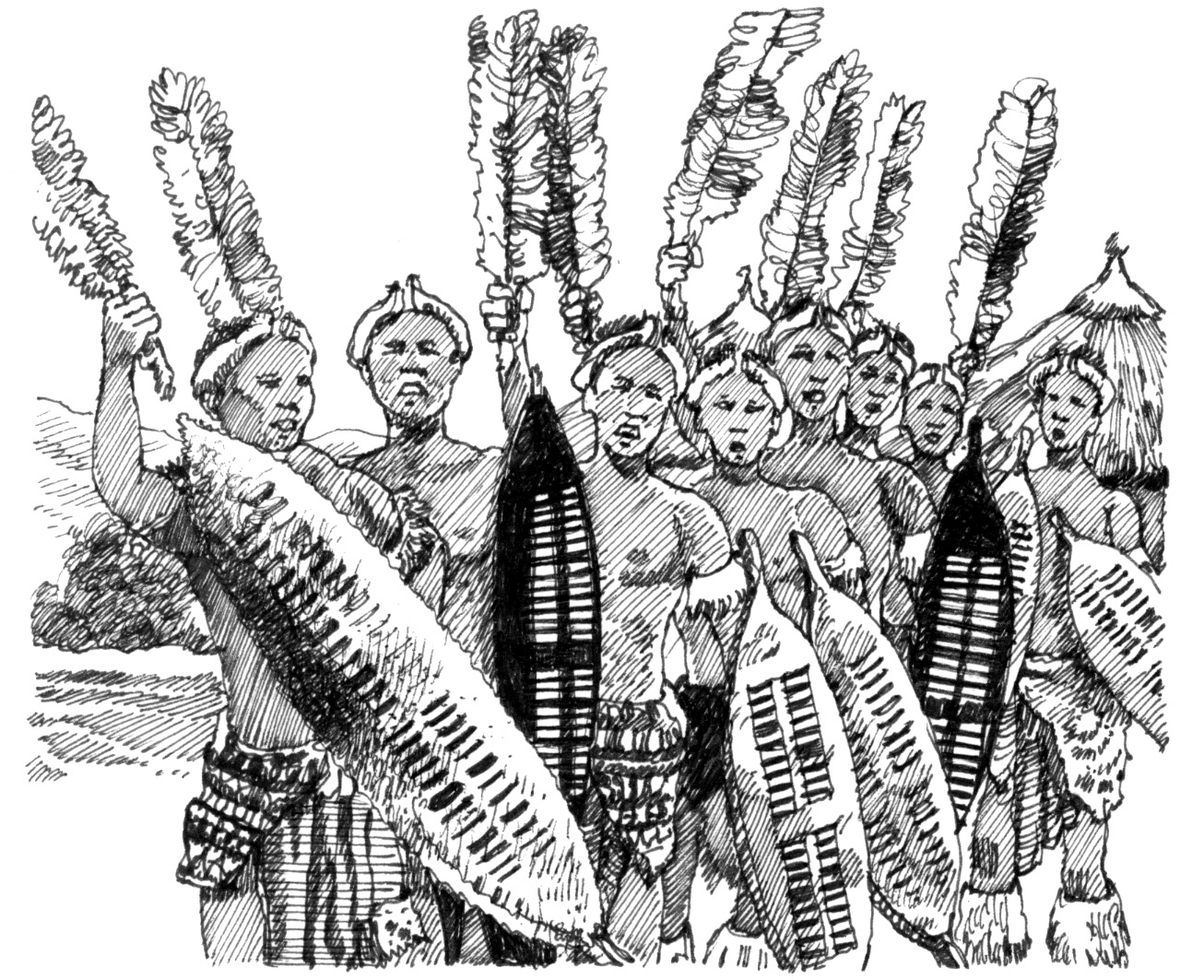

When Nelson was sixteen, he and Justice took part in an important ceremony where they became men in the eyes of the village. After the ceremony a tribal leader made a speech. “Among these young men are chiefs who will never rule because we have no power to govern ourselves,” the man said.

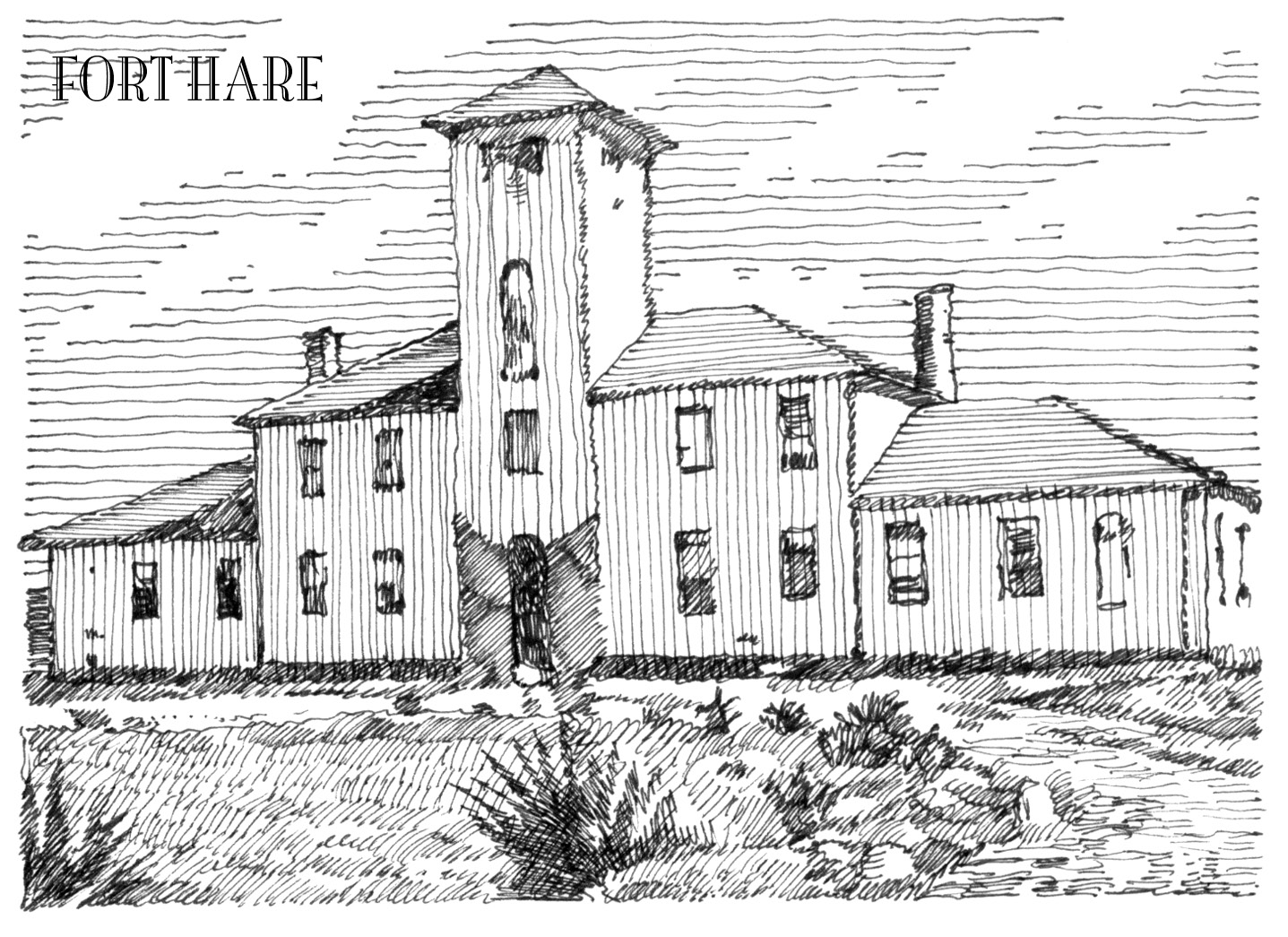

Governing was exactly what Nelson wanted to do when he grew up. He attended a boarding school in Engcobo so that he could one day advise rulers like Jongintaba. Then in 1937 he transferred to Healdtown, a church-run college. From there he went to Fort Hare, the only all-black college in the country. Many white South Africans thought that all black people needed to learn was how to serve white people. Schools like Fort Hare gave black South Africans bad ideas, they thought. They made black people think they were as smart as white people and could compete with them for jobs.

Fort Hare did give Nelson ideas. He began to study the world outside South Africa. Nelson planned to one day work for the Native Affairs Department, which enforced laws such as the “pass laws” requiring all black South Africans to carry a passport all the time. He hoped to change the laws so that black people would be treated better. He worked hard in school to reach his goals.

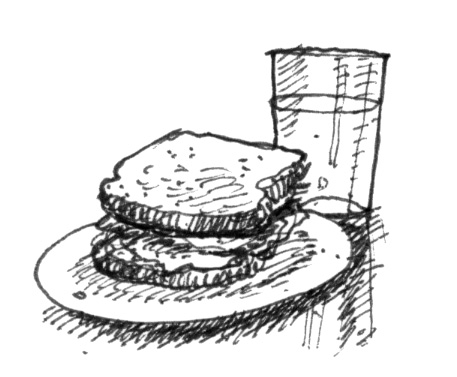

But in 1940 Nelson resigned from the Students’ Representative Council in protest of the bad conditions in the dorms. “Supper was four remarkably thin slices of bread,” Nelson’s college friend Oliver Tambo would later say, “taken with a small cup of milk water.” The school authorities said any student resigning from student government would be expelled from school. When Jongintaba found out that Nelson had left school he ordered him to return.

He also ordered him to get married. He had found Nelson the perfect bride. She was “fat and dignified,” Nelson said later. Some say she was in love with Justice.

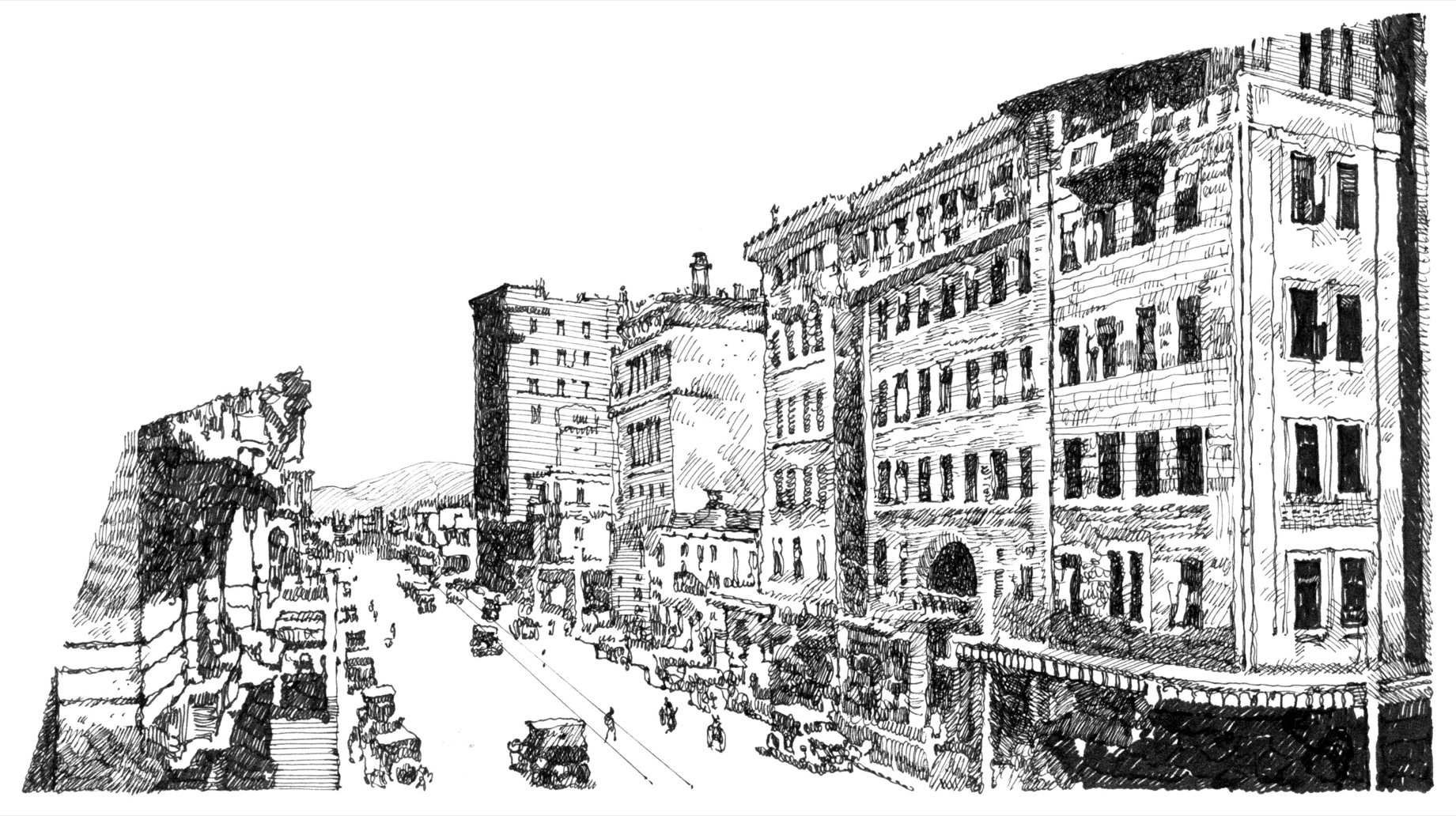

Neither boy wanted to get married yet. So they ran away to the greatest city in South Africa. To Nelson Mandela, Johannesburg looked like a city of light. “A vast landscape of electricity,” he called it.

He and Justice got jobs, but were soon caught by Jongintaba’s men. Justice had to return home to take his father’s place one day. But Nelson convinced his foster father to let him stay in the city and study law.

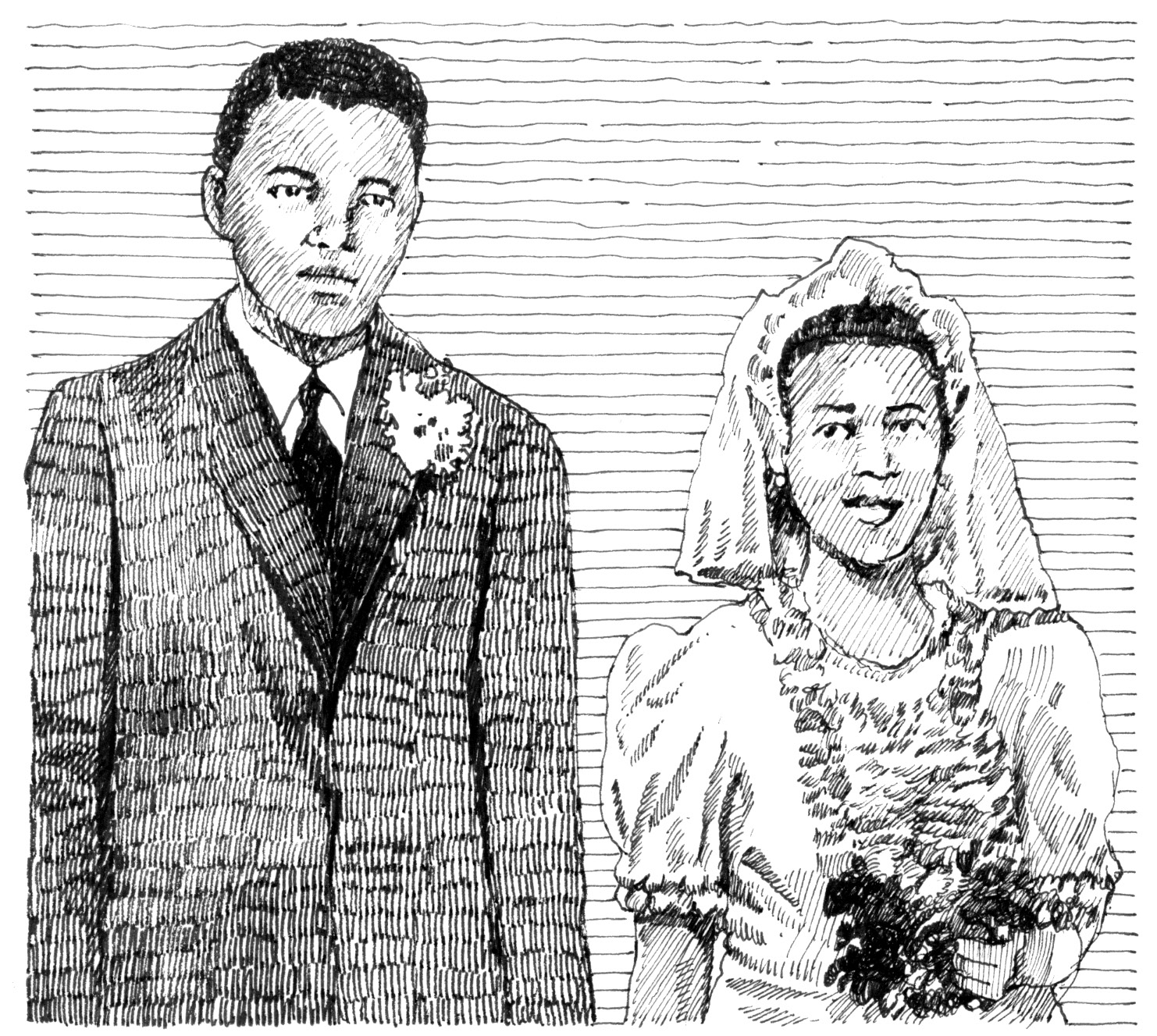

In Johannesburg, Nelson made new friends like Walter Sisulu. Sisulu was the son of a black cleaning lady and a white government official. He had worked many different jobs and led strikes for better wages for black workers. Sisulu got Nelson a job at a law firm. He also encouraged Nelson to enroll at a local university as a law student. Nelson married Sisulu’s cousin Evelyn in 1944, and they soon had a son, Thembi.

That same year Nelson joined the African National Congress. The word congress did not mean it was part of the government. It referred to a group of many people all working for the rights of black South Africans. When it was first founded in 1912 the ANC led protests against the pass laws. But by the late 1930s it had become powerless. Nelson and his friends started a new group within the ANC called the Youth League. The Youth League led the ANC to challenge the government. For the first time the ANC openly accused white South Africans of not having the best interests of black South Africans at heart. Nelson became so wrapped up in the struggle he hardly ever saw his young family.

It was hard to imagine the white government in South Africa getting any worse for black people. But in 1948, it did. The government of South Africa started a cruel system of segregation, a way of keeping people of different races apart. In English the word for this system meant “apartness.” In Afrikaans, the language of Dutch South Africans, it was called apartheid.