Chapter 7

Robben Island

While Nelson was in prison, the police searched Liliesleaf and arrested Walter Sisulu and other members of Spear of the Nation. Luckily Oliver Tambo was outside South Africa. When he heard about the arrests he knew he couldn’t go back. He was as determined as ever to help his friends.

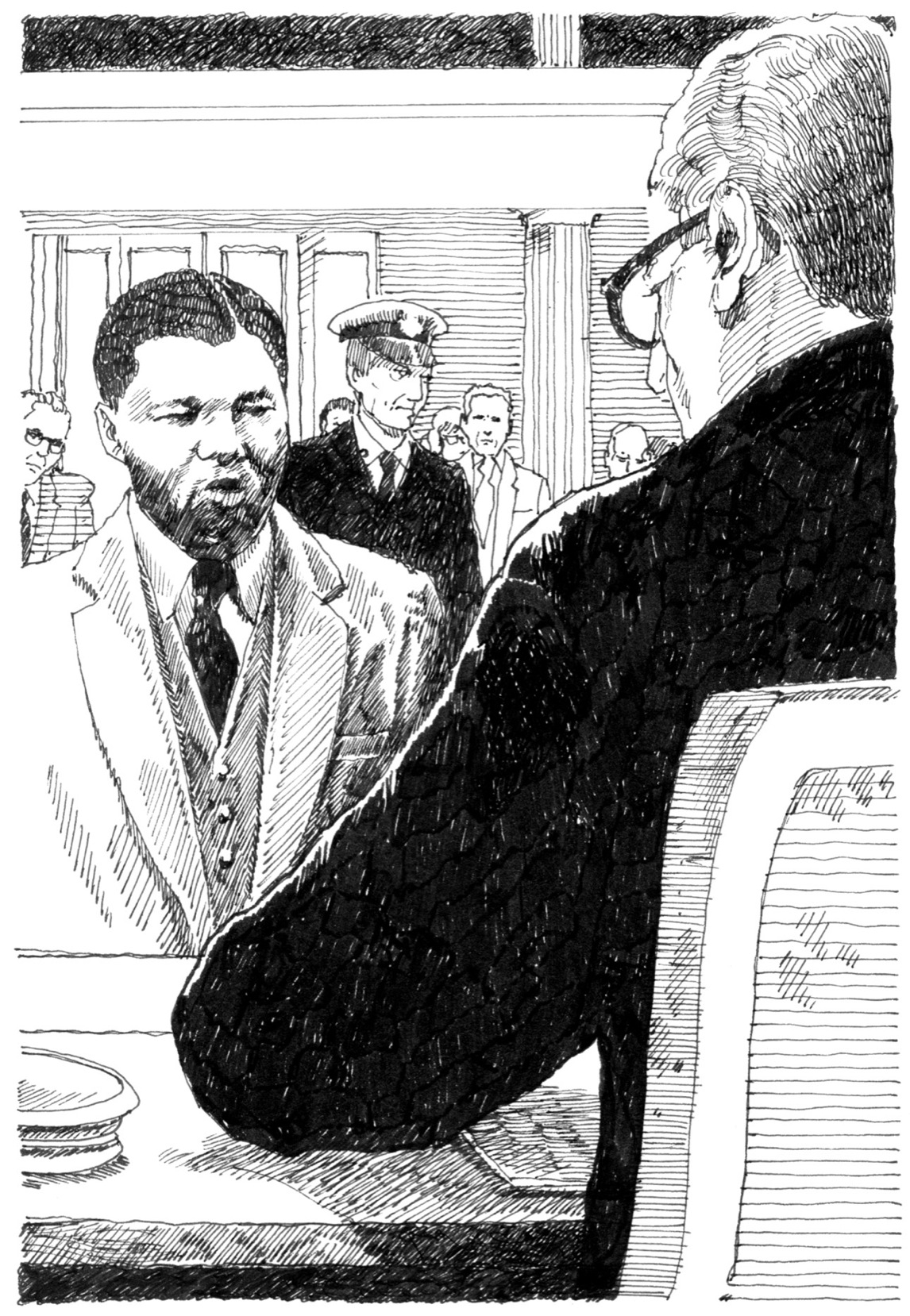

In October 1963, Nelson went on trial again. He was accused of 222 acts of sabotage between 1961 and 1963. Sabotage means to destroy or disrupt things so that they don’t work. For instance, Spear had plans to set off explosions in police stations and other government buildings (but not when people were around). The state asked for the maximum penalty: death by hanging.

The courtroom was tense. The lawyers against Nelson and his friends took five months to present their argument. Then, in April, Nelson stood to speak. His elderly mother and his wife watched from the gallery. He offered no evidence in his defense. Instead, he made a statement. “We believe that South Africa belongs to all the people who live in it,” he said, “and not to one group, be it black or white.”

Nelson spoke about the unjust laws, life in the crowded townships, and the cruel actions of the government. He spoke on the right to vote, the right to an education, and the right to be treated with basic respect. For hours the courtroom listened, spellbound. “I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people . . . ,” Nelson said. “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

After the trial, the judge sentenced Nelson and the other defendants, including Walter Sisulu, to life in prison.

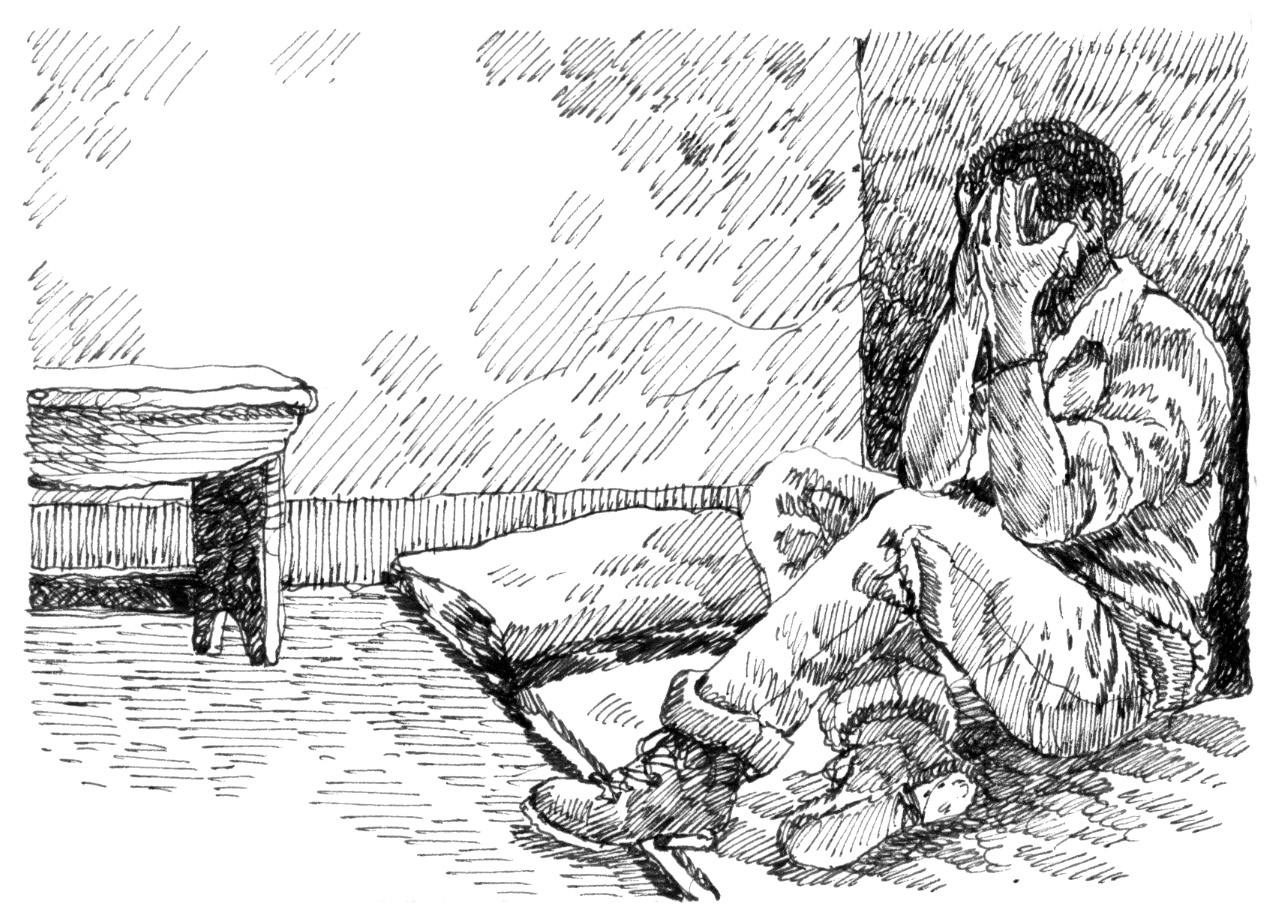

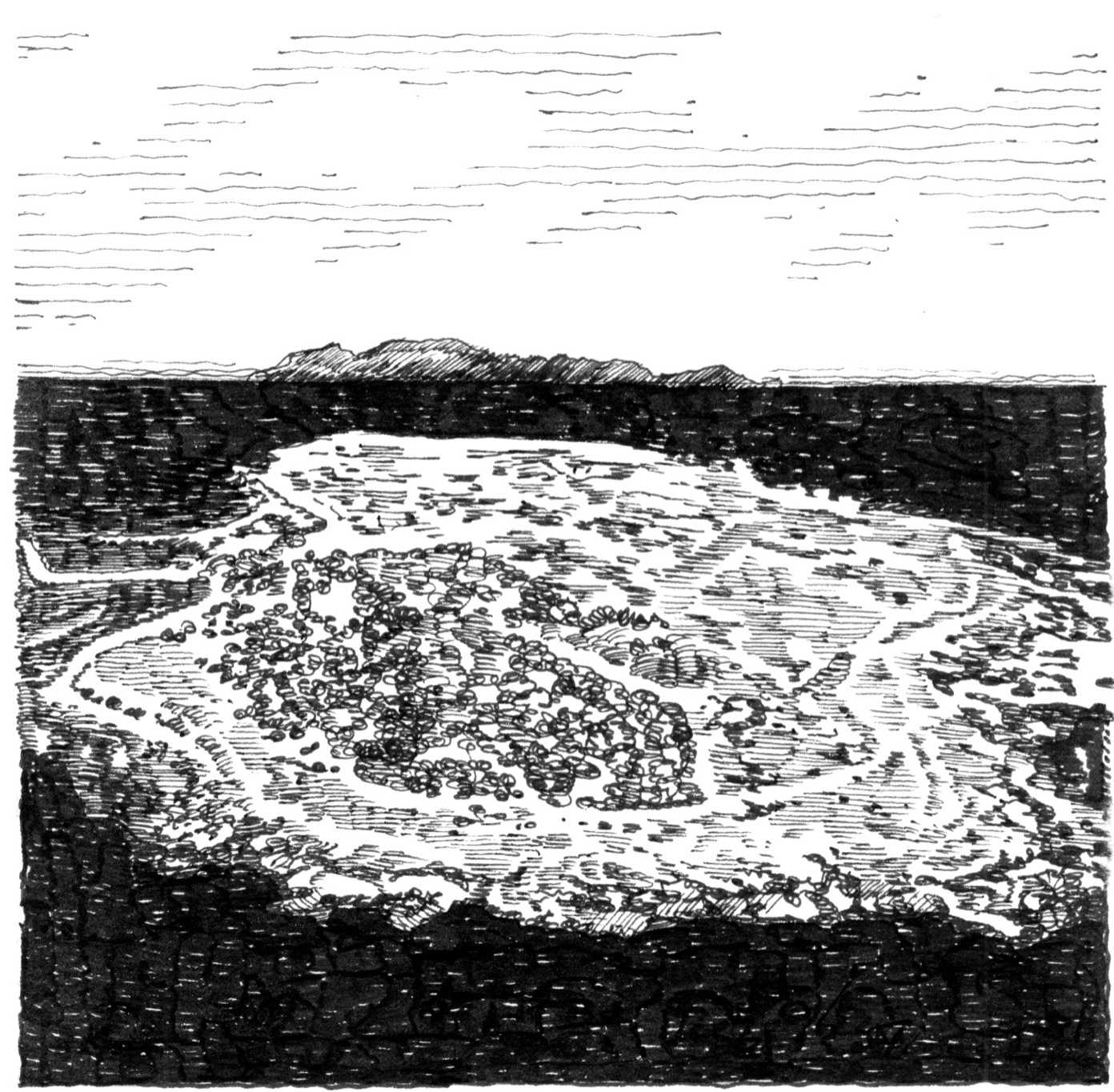

Nelson and Sisulu were flown to a maximum-security prison on Robben Island off the coast of Cape Town. No ships were allowed within a mile of the island. Escape was impossible. Mandela was led to the cell that would be his home for the next eighteen years. It was eight feet wide and seven feet long, lit by a single forty-watt lightbulb. The bulb stayed on day and night. Mandela could walk across the room in three steps. There was a mat for sleeping and three blankets so thin he could see through them. His toilet was a small iron bucket.

All the prisoners on Robben Island were black. All the guards were white. Mandela could write to his family and receive a letter from them only once every six months. Before Nelson was allowed to read a letter, prison officials crossed out anything in the letter they didn’t think Nelson should see. Often so many words were crossed out, the letter barely made sense. Nelson did not see Winnie for years at a time. He was not allowed to attend the funerals of his mother or his eldest son, Thembi, who died in a car accident in 1969.

Every day, he was woken up at five thirty. He washed and shaved with cold water. He emptied his iron bucket. He was allowed eight squares of toilet paper a day. He ate tasteless porridge for breakfast. Then he went to work—either breaking rocks in the courtyard or working in the limestone quarry digging out heavy slabs of rock with picks and shovels and lifting them onto trucks. The sun was so bright on the limestone it damaged his eyesight. In the summer it was boiling hot; in winter, cold and windy. The lime dust stung his eyes and made his hands blister.

Information about the outside world came from new prisoners, except when guards left newspaper clippings on his sleeping mat to let him know that—back in Johannesburg—Winnie was being harassed and jailed. They did this to show Nelson how powerless he was to help his family.