Gem Lake and Lumpy Ridge Trails

“How could 1.7 miles be so long? When do we reach the darned lake, anyway?”

Such reactions are frequent among the many hikers who are lured onto the Gem Lake Trail because it seems fast and easy—the lake is only a 1.7-mile walk from the trailhead closest to Estes Park Village. The trail, however, winds through open south-facing ponderosa pine woods at a lower altitude than most park paths; thus midday heat in summer can sap hikers’ energy significantly.

Many folk are disappointed by the Gem Lake hike, but their disappointment arises from their inability to see and understand the fascinating natural events occurring at trailside. With a quart of water per person, three hours to spend, and a knowledge of what to look for, the Gem Lake Trail is unique and enjoyable. It is best hiked early or late in the day, not only for physical comfort but also for grand vistas of dramatic light falling on the Front Range.

To reach the Gem Lake and Lumpy Ridge trailheads, drive north on MacGregor Avenue (which becomes Devils Gulch Road) from the intersection of MacGregor Avenue and the US 34 Bypass of Estes Park. About 2 miles from Estes Park, a left turn to the trailheads is well marked along Devils Gulch Road.

Also well marked are the adjacent trailheads. The Lumpy Ridge Trail (on the left) provides access to a multitude of spectacular cliffs. The routes up these faces make Lumpy Ridge a heaven for rock climbers. Most spectacular of these rock formations is Twin Owls, easily visible from Estes Park and so obvious in its name that even I can see it.

Nature Walk to Gem Lake (Montane Zone)

The parking lot is a good place to visualize the broad outlines of the geology of Lumpy Ridge experienced on the way to Gem Lake. Forty million years ago (give or take a day or two), the ridgetop was part of an ancient plain. It was raised to its present position a mere five to seven million years ago, by which time the plain had been deeply penetrated by weathering, the process that breaks up rocks and decays them into soil. This decay had occurred along a network of fractures in the granite underlying the plain. As the sides of granite blocks outlined by fractures disintegrated, their unweathered cores remained as solid rock surrounded by weathered debris. The debris later eroded away, especially as the ridge was raised.

The cores are the “lumps” of today and also the huge boulders that eventually tumbled down the slopes of Lumpy Ridge. The boulders could easily be mistaken for rocks deposited by melting glaciers, but glaciers never extended to this spot.

The rounded appearance of the rocks comes from the way in which they weather. Masses of granite in areas of slight rainfall split off plates or shells in successive layers like those of an onion. The process, called exfoliation, begins when water invades tiny cracks in the granite and dries more slowly than on the surface. Some minerals in the granite are slowly dissolved by the water, forming a claylike material. The clay expands, pushing off granite plates parallel to the surface.

The action, of course, takes a very long time. We casually overlook millions of years here and there throughout Lumpy Ridge geology. Human life is too short and human experience too limited to enable most imaginations to encompass so long a period of time.

The trail begins amid ponderosa pines, Douglas-firs, quaking aspens, and chokecherry bushes. The latter is the most common wild cherry (Prunus virginiana); varieties of this marvelous shrub grow throughout most of the United States. The long white flower clusters have an almost overpoweringly sweet odor in spring. The blossoms evolve to masses of dark purple or black cherries, much favored by birds and jelly makers. In fall the leaves of the bush turn orange-red.

In the drier areas along the trail, two kinds of juniper grow. Common (or creeping, or dwarf) juniper is a low shrub with short, sharp needles. Rocky Mountain juniper (often called cedar) is a small, many-branched tree with flat scalelike foliage. The female plant of both kinds bears blue cones with a waxy covering that makes them resemble berries. Juniper “berries” are used to flavor gin. They are not tasty, and after an experimental nibble, few hikers venture to try more.

Wild rose is another common and edible-if-you-are-desperate shrub on the first part of the Gem Lake Trail. Rose hips, the fruits that follow its fragrant pink flowers, are well known as a source of vitamin C. These red fruits taste no better than bland, mealy apples; they also have annoying hairy seeds. So unless an advanced case of scurvy is causing your teeth to fall out, it would be best to leave the rose hips to grow prettily and to be eaten by the wildlife that favors them.

Another shrub popular with wildlife is antelope bitterbrush; it has many branches, small leaves, and small yellow blossoms in May and June. Yes, it tastes very bitter, but it is an important browse plant for mule deer. (In the second half of the nineteenth century, market hunters wiped out the antelope of the plant’s name in the Estes Park area.) Growing among the rocks and in draws on the hillside is Rocky Mountain maple. Although the leaf’s shape is familiar to most hikers, this many-stemmed shrubby representative of a noble and valuable family seems like a stunted poor cousin. Well, it is the only maple we have, and we like it! It puts up with excessive dryness and poor soil that the big, showy maples never could tolerate. In size and shape it reflects the general harsh austerity of the West, yet in fall its leaves turn a showy red and yellow like the magnificent sugar maple of the East.

Ponderosa pine is the dominant tree in the montane zone of vegetation through which the trail passes. It has moderately long needles growing in bundles of two or three. The bark of young ponderosas is dark gray; that of mature trees is thick, deeply grooved, and rusty red. These picturesque mature pines, which may be as old as 500 years, stand apart from one another, giving a ponderosa woods an open, parklike appearance.

Perhaps the most interesting inhabitants of ponderosa forests are the tassel-eared Abert’s squirrels. They are the most magnificent squirrels in North America and need no description beyond that of the children who call them “squabbits”—squirrels with rabbitlike ears. Abert’s squirrels come in two distinct color phases, black and gray-and-white, and there are some dark brown individuals.

Less spectacular but more pugnacious are the red squirrels, which are more gray than red and inhabit the higher reaches of Lumpy Ridge. Red squirrels are very common in the subalpine zone along other park hiking trails, for instance at Bear Lake. Chipmunks (striped back and face) and golden-mantled ground squirrels (larger, with striped back and plain face) also abound. Near the base of the trail, you may notice unstriped Richardson ground squirrels. Locally they are called gophers. Yellow-bellied marmots, western cousins of the woodchuck, are often seen sunning themselves on rocks.

Rocky Mountain National Park

Common birds to watch for as you hike toward Gem Lake include tiny pygmy nuthatches, mountain chickadees, yellow-rumped warblers, gray-headed juncos, and raucous Clark’s nutcrackers. Two thrushes seen more frequently along the lower part of the trail than in other areas of the park include Townsend’s solitaire and the rust-and-blue western bluebird, which is not to be confused with the very common blue-and-gray mountain bluebird.

You may spot winged hunters soaring above Lumpy Ridge, looking with hawk eyes for any of these small birds or mammals. Most common of the hunting raptors is the red-tailed hawk, which seeks squirrels for lunch. The much larger golden eagle also dines on marmots or even coyotes. Birds are the preferred prey of the endangered peregrine falcon. Some parts of Lumpy Ridge may be closed to the public during spring and early summer to protect raptor nesting habitats. The exact sites change and are indicated by notices nearby; usually rock climbers more than hikers are affected by these closures.

In the moister areas among the ponderosas, Douglas-firs grow in groups or singly. Their cones, with three-pointed bracts protruding from under the scales, are quite distinctive. In the Pacific Northwest, the Douglas-fir grows to a huge size and is extremely important for lumber. In our semiarid climate, however, a specimen a yard in diameter qualifies as an old giant. Douglas-fir grows most often in cooler north-facing slopes where snow melts more slowly because it is protected somewhat from sunshine. Gulches provide the same shade as well as pathways for slight water flow, which further aids the Douglas-fir.

Hikers notice dead pines killed by mountain pine beetles. Now and then you will see lightning-killed trees too. Beetle trees are good hunting grounds for hungry woodpeckers such as common flickers, whose red wings and white rumps flash in flight. Woodpeckers also excavate nest cavities in the dead trees, providing holes essential for subsequent nests of swallows, bluebirds, wrens, chickadees, and nuthatches.

In especially dry and sunny areas, prickly pear cactus begins to appear. The blooms in June are a showy yellow and red. The big, nasty-looking spines at all times of year are a dramatic warning to keep away. But they are not dangerous—if you do not kick or sit on them. The real threat comes from the minute spines growing close to the surface of the fleshy stem.

In a national park, the prickly pear, like everything else, is left unmolested. Elsewhere, where it is more abundant, it is gathered and eaten, and then the small spines come into play. The big spines are easy to break or burn off, but the little ones seem immune to any type of removal. Most folks cannot even see them without a hand lens; under magnification the rows of barbs on each spine stand out like fishhooks. The barbs can work their way into the flesh of careless hands and cause pain for days.

The small spines were found by an archaeologist in 90 percent of the feces collected from ancient ruins at Mesa Verde National Park. Not content with the romance of examining centuries-old feces, the archaeologist tried eating fresh prickly pear with its tiny spines intact. Oddly, martyrdom for science was not the result. The only negative sensation was a prickling of the tongue. Please refrain from this kind of experiment though—especially in national parks!

A safer if not better-tasting addition to the Native American diet was squaw currant, which grows abundantly along the trail as it climbs the ridge. This bush has the typical rounded, lobed leaf of a currant and trumpet-shaped pink flowers that ripen to red berries. The berries are used by some jelly makers, but they need much spicing up to make the product more than insipid. They are, however, an important food for birds and small mammals.

Where Lumpy Ridge is exposed to high winds, especially in winter, grows limber pine (Pinus flexilis), whose tough, flexible branches bend easily in the wind but rarely break. This tree normally is associated with the tree line, several thousand feet higher on the mountains, but sometimes grows as far down as the plains. Its needles are shorter than the ponderosa’s and grow five to a bundle.

The trail climbs eventually to the edge of an aspen grove in an often dry creekbed, where there is a heavy growth of bracken ferns. Soon excellent views beckon to the south and west, necessitating short detours from the trail. Looking south, you will see the bumpy summit of Twin Sisters across the valley east of Longs Peak, the tallest mountain in sight at 14,259 feet. Lake Estes and associated civilization are obvious in the valley immediately below you.

Essentially similar views continue until the trail turns into a shady canyon with a small stream. The canyon is refreshingly cool, and out-of-place Engelmann spruce has found a foothold similar to its usual home higher in the subalpine zone. An occasional subalpine fir also grows here. Aspen, water birch, chiming bells, shooting star, and other moisture loving plants, along with mosquitoes, inhabit this oasis.

After crossing the stream, the trail is closed in by canyon walls. Exit is via two series of short switchbacks, at the top of which appears Paul Bunyan’s Boot, a rock formation that is a “must” photo. Chemical weathering even has put a hole in the boot’s sole.

Natural sculpture and balanced rocks are common on Lumpy Ridge, as are potholes in the granite. On cliffs above Gem Lake, itself a big pothole, these formations of chemical and mechanical weathering seem too fantastic to be natural, more like a Disneyland invention.

The hollowing out of rock basins begins when falling rain picks up a little carbon dioxide from the air to form extremely mild carbonic acid. The acid tends to break down certain granitic minerals into various clays. Some of the rock surfaces are structurally weaker and more susceptible to this chemical weathering than are the surrounding surfaces. Further weak acids formed by accumulations of decaying vegetation can accelerate pothole formation, as can wind and frost wedging, expansion of ice that enlarges cracks in rocks. Weathering sometimes creates holes all the way through rock.

Below Gem Lake there are three series of short, steep switchbacks built to make the trail easier for horses, not for humans. The trail emerges from trees to run along steep-walled rock slabs, which collect the sun’s warmth and radiate it back on hikers. You get steadily hotter and then face one more long, dusty switchback to reach the lake—at last.

“Ugh, that’s it?” is the standard reaction. Folks expecting a typical alpine lake are always disappointed. Gem covers only two-tenths of an acre, with a maximum depth of 5 feet and an average depth of 1 foot. It is stagnant, fed by rain and snowmelt, with no visible outlet. Various interesting but unglamorous creepy-crawlies call it home.

Yet Gem is a joy, for there is no other body of water like it in the park. White-throated swifts, uncommon elsewhere, dip and soar over the lake. Picturesque limber pines and Douglas-firs decorate the sandy shore. Stroll 200 feet to the opposite end of the lake, where pine branches will frame a photo of Gem with spectacular peaks in the background. Details of the patterns made by orange lichens on the rock cliffs provide additional good picture subjects. The examples of exfoliation and chemical weathering are unexcelled, and the acoustics of this natural amphitheater are such that your heartbeat seems to echo.

Around the corner of the cliff at the north end of the lake is the easiest route of ascent to the top of the cliffs, about 200 feet above. It is worth the climb for the different photographic perspective of the lake, fantastic potholes, and views of the surrounding peaks.

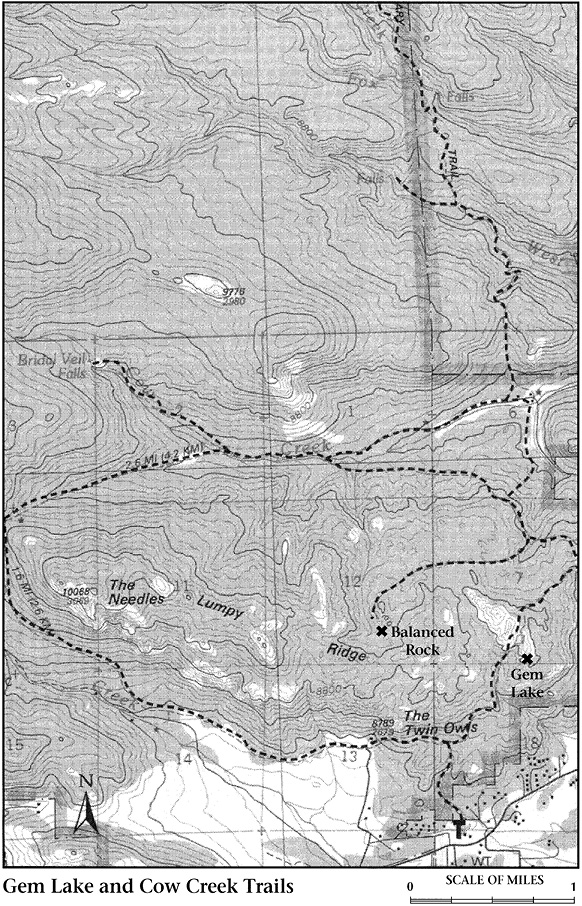

The trail continues north and descends 0.25 mile from Gem Lake to a fork. The right branch is an unmaintained trail that cuts across private land at its bottom. Public access is disputed, and I recommend that you not bother hiking this trail.

The left branch descends a short way to level walking until another fork is reached 0.5 mile from the first. A left turn winds down among more Lumpy Ridge lumps into a gully containing the most interesting lump of all, Balanced Rock, about 2.0 miles from Gem Lake. Take the right fork, which descends to yet another split. The trail cutting right drops down to the old McGraw Ranch. Bear left to open meadows and the Cow Creek Trail. A right turn here takes you to Cow Creek Trailhead at McGraw Ranch. (There’s an emergency phone at this trailhead.) A left turn leads to Bridal Veil Falls or Black Canyon. It is possible to trace your way down Black Canyon on the Lumpy Ridge Trail back to the parking area. This circuit around Lumpy Ridge is roughly 9.0 miles.