The kid across the street is named Aaron Peterson, and his house is made of doors. Not really, but it feels that way. The first time I go over, I open three doors before I finally find the bathroom. Then I go to the kitchen for a glass of water and get lost trying to find his room.

“Don’t feel bad. Everyone gets a little turned around at first,” he tells me after I finally find my way back. Then he shrugs. “Old houses are weird.”

I nod like I agree, but I’ve lived in old houses. The turquoise house is old, too. None of them have been like this one, though, with side staircases that lead to little half landings, and some doors that don’t even open.

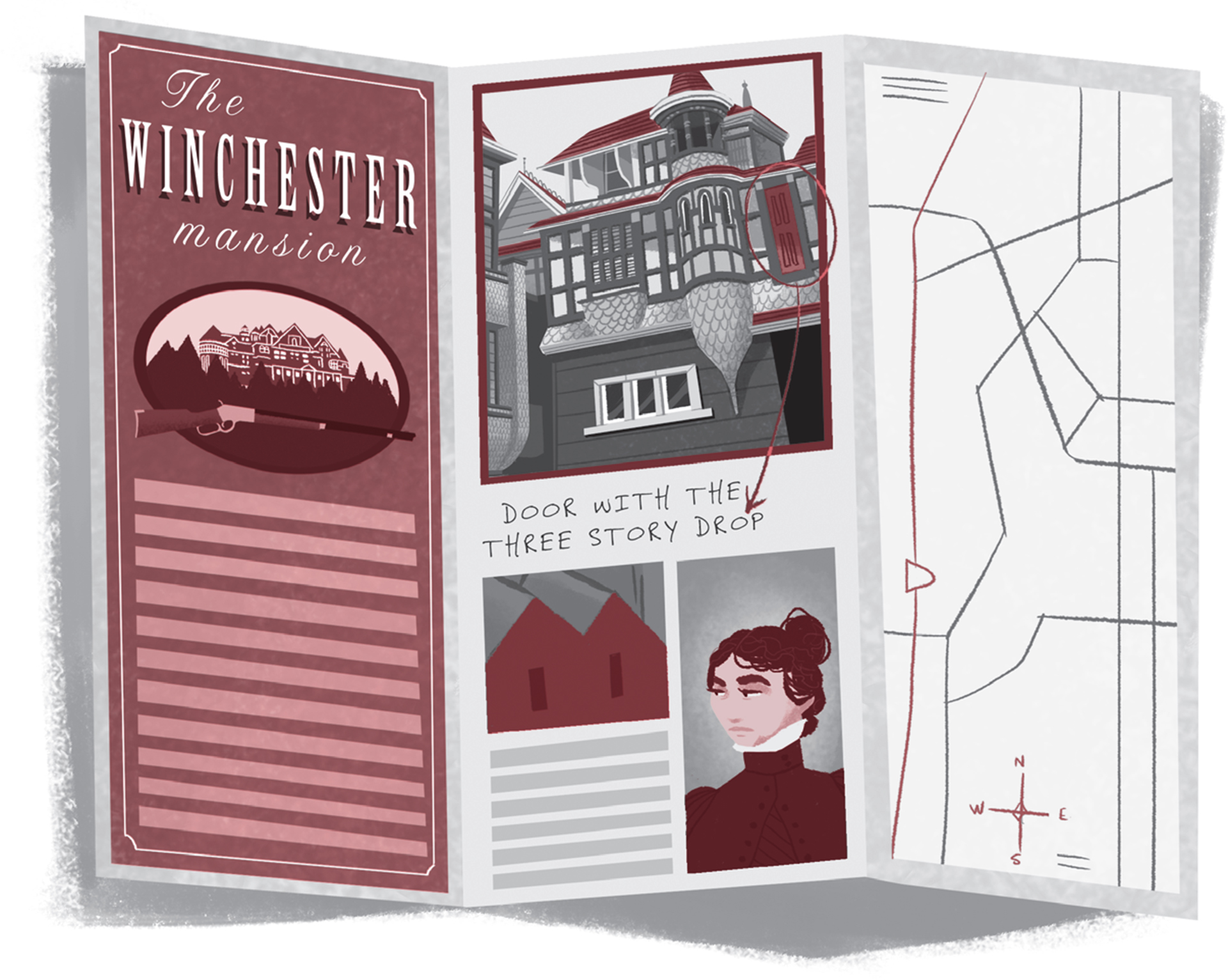

When I was seven, we lived in Northern California for a few months while my dad was still a beat reporter. My mom, always up for a good ghost story, took me to the Winchester mansion, where we got to tour the house that was perpetually, obsessively built by the widow of the famous Winchester rifle maker. The story went that someone told her she and her family were being haunted by the thousands of people who’d lost their lives to her husband’s gun company. She kept the builders working day and night on a house she would never finish building so the ghosts couldn’t find her in the maze of a mansion. The clearest memory I took away from the tour was a door that opened to a three-story drop. I imagined a sleepy seven-year-old me staying in that twisty house, waking in the middle of the night looking for someplace to pee and dropping to my death after pulling the wrong knob.

“We don’t have one of those,” Aaron tells me when I relay my memory to him the next day. “At least I don’t think we do.”

He says it so casually, I don’t think he realizes how strange it is that he could live in a house and not know where every door leads. At least, at first it seems strange to me. Then I learn that there are some places in Aaron’s house that are off-limits.

“The basement’s kind of a wreck,” he says, but now he’s less casual about it. Now he seems uncomfortable. I think back on the boarded-up door on the side of their house, the one I thought led to a root cellar.

Aaron doesn’t have white hair, as it turns out. That was a trick of the flashlight, just one of the many weird aspects of the night he introduced himself to me. It’s just light brown, but that’s about the only ordinary quality about Aaron. He’s tall—in fact, at first I thought maybe he was older than me. He’s my age, though, and he acts like he’s fifty. It’s like the Giant Alien Overlords sucked all the childhood out of him and left behind a twelve-year-old adult. It’s not that he doesn’t smile or joke. He just has … purpose.

He’s also better at picking locks than me. He can find his way into the tiniest keyhole, his hands steady and precise. But that isn’t why he’s good. It’s his patience that makes him better than me. He can sit in a turn and twitch the pick a millimeter, feel for the movement, then guide the tool through a different path, until boom! The lock springs free, and the door opens.

“I should’ve gone with the rake,” I say, angry at myself for not springing the hall closet upstairs that particular afternoon.

“I’ll give you an easier one next time,” he says, punching my shoulder a little too hard.

I punch him back harder. “Man, don’t be a—”

“A what?”

Broad shoulders and an argyle sweater emerge from a door behind us that I swear to the Aliens I didn’t even know was a door.

“Uh …”

“Dad, this is Nicky. From across the street.”

“Nicky from across the street,” Mr. Peterson says, pinching an end of his curled mustache like a cartoon villain. And he looks like he could be a villain, with his wide eyes hooded by thick eyebrows and forearms bigger than my legs. If not for his unmistakable dad uniform—violet-blue sweater, brown pants, high socks—I’d be halfway across the street by now.

He didn’t ask me a question, but he’s looking at me like he’s waiting on an answer.

“Uh, we were just …”

Picking locks in your house.

Fighting.

Cursing.

Mr. Peterson leans over and puts his hands on his knees, large shoulders framing the face that’s now six inches from mine. His carnival mustache is practically touching my cheek. I can smell spearmint on his breath.

“Well, Nicky from across the street,” he says, and I clench my teeth together to keep them from chattering.

He leans in even closer, and I think I’m going to faint.

“How would you like … to stay for dinner?”

He pauses and waits for me to process what wasn’t the threat it sounded like, and then his mustache lifts to reveal a row of brilliant white teeth. He leans back, tilts his head, and bellows a laugh that shakes the hallway I nearly pee myself in.

I start to laugh, too, because I have no idea what else to do. I feel Aaron grab my arm and drag me down the stairs, muttering something about “Don’t know why you have to be so weird” and shoves me down the hallway so I can gather myself and wonder if he was calling his dad weird or me.

I start to head down a different hallway before Aaron redirects me. Just one more rabbit hole to fall through in his winding house.

In the kitchen, Aaron’s ten-year-old sister is wielding a seriously sharp knife over a yellow onion while Mrs. Peterson smokes a cigarette with her back turned. Aaron told me his mom teaches first grade at Raven Brooks Elementary.

“Cripes, Mya, give me that.” Aaron lunges toward the cutting board and catches the handle of the knife just as Mya begins to pierce the wobbly onion against the wood.

“Mom asked me to,” she says defensively, but she looks relieved.

“You know I’m a crier,” Mrs. Peterson says, exhaling a stream of smoke through the kitchen window screen.

“I have freakishly strong eyes,” Mya says, her pride returning after being stripped of her duties. She’s Aaron’s polar opposite, with light red hair like her mother’s. She shares her mother’s small frame, too, with stubby little legs that make her look younger than she should.

Aaron slices the onion into fine rings and sets the knife and cutting board in the middle of the kitchen island while Mya wipes the onion skin from where it got caught on her watch.

“Thanks, baby,” Mrs. Peterson says, stubbing out her cigarette and planting a kiss on top of Aaron’s head, then one on my head, and I turn away when my face gets hot, and for some reason, Mya’s face gets red, too. Mrs. Peterson lets me call her Diane, but it feels so weird I’ve just stopped calling her anything at all. I guess she’s pretty, but she reminds me so much of my mom it’s nuts.

I’ve tried to get Mom to invite the Petersons over for dinner, but Mom’s formal about stuff like that. “They should invite us first,” Mom says, and that’s that.

“Hamburgers for dinner tonight,” Mrs. Peterson says. “You boys planning on sticking around, or are you robbing banks this evening?”

I turn to face the wall again because I had a dream last night that I cracked a bank vault, and the rush I felt was so strong I felt a little awkward when I woke up. I’m pretty sure that’s not using my powers for good.

“Who’s robbing banks?” Mr. Peterson says, emerging once again from whatever kind of shadow a hulking guy in argyle can hide in.

“Oh,” Mrs. Peterson says, peering into her mixing bowl. “We might not have enough hamburger if you stay, Nicky. Aaron, you’d have to run to the store for some more.”

“Batty Mrs. Tillman stopped selling meat, remember?” Aaron says.

“Oh, that’s right. I keep forgetting that,” says Mrs. Peterson.

Aaron turns to me with a wicked smile. “We could get you a tasty bulgur-wheat-and-tofu burger, though. Maybe a cocoa-powder granola bar for dessert.”

“Whatever, you love those bars,” Mya says, curling her lip.

“It’s true,” Aaron says, leaning toward me. “They make you fart.”

Mya dissolves into giggles.

“A lot.”

“What’s the verdict on dinner?” Mrs. Peterson asks, bringing us back on topic. “You boys in or out?”

“We’re eating at Nicky’s,” Aaron says, and when I look at him, he widens his eyes.

“Right. At my house,” I say, not much better at lying than Aaron is.

Mrs. Peterson examines us from across the kitchen island. Mya swoops in to save the day, though, bringing us back to a forgotten topic.

“Everyone thinks that Jesse James was the best bank robber there was, just because he was a show-off, but he couldn’t have done any of that without his brother, Frank. People always forget the siblings.”

“I’m sure you could rob a bank just as successfully as your brother, Mouse,” Mrs. Peterson says, lining the patties into perfect rows on the cutting board. She holds a meat tenderizer high above her head and brings it down with startling strength, moving from patty to patty with unsettling enthusiasm.

Mya rolls her eyes, but I can tell she likes when her mom calls her Mouse, just like I don’t mind that my dad still calls me Narf. My parents claim that’s how I used to say my name before I could say Nick, which is weird because it doesn’t even sound the same, but whatever. It stuck, so now I’m Narf, and from some of the nicknames I’ve heard out there, it could be a whole lot worse.

“And I’m sure your brother wouldn’t dream of taking credit for your accomplishments,” Mrs. Peterson adds, winking at Aaron.

She brings the meat hammer down on the patty again, and I jump before I can catch myself.

“Remember, family makes you stronger,” Mrs. Peterson says. “Isn’t that right, honey?”

Mrs. Peterson turns her head to the side to address her husband, but her eyes never meet his. Mr. Peterson just stands there for a second, surveying his family across the kitchen island before moving to the sink to wash his hands.

“Not necessarily,” he says with his back turned to us all, and from the way he says it, I can tell that’s all he wants to say on the subject.

Either Mrs. Peterson doesn’t notice or she doesn’t care. “Oh, don’t be a grump. You don’t really mean that.”

Mrs. Peterson flashes me a smile and rolls her eyes, which might be convincing if her hands weren’t shaking so hard she has to set down the meat tenderizer.

Mr. Peterson scrubs his fingernails meticulously at the sink. I sneak a glance at Aaron, and he’s watching his dad, too. Mya’s moved to the other side of the island, and she’s fidgeting with the ties on one of the barstool cushions. I’m waiting for the punch line, for Mr. Peterson to whip around and bark that insane laugh from under his mustache, but he doesn’t turn around.

Mrs. Peterson tries a joke. “Well, I’m afraid you’re stuck with us, darling. We’re Petersons to the bone.”

Now Mr. Peterson does turn around, so fast that the towel in his hands makes a whipping sound in the air.

“You know what’s so interesting about bones, Diane?” he says with a smile that’s way different than the one he cracked in the hallway upstairs. This one bares both rows of his teeth, and they don’t part. He just talks right through them.

Mya moves a little closer to Aaron. I think I do, too.

“Not all of them are necessary.”

Mya reaches for Aaron’s hand, and he squeezes hers back.

“It’s true,” Mr. Peterson continues, even though no one contested it. “It’s remarkable what the human body can survive without. Pluck one bone out, and the body keeps on living.”

Mrs. Peterson is shaping the hamburger patties, and she’s been working on that same patty since her husband started talking; I don’t think she’s thinking about hamburgers anymore. She closes her eyes, and I want to close mine, too, but I’m afraid to look away.

“There’s just one bone you can’t live without … the funny bone!”

Mr. Peterson runs to Mya and scoops her up by the waist, and for a panicked second, I think he’s actually going to hurt her. But she starts giggling immediately, and her giggle turns to a frantic laugh, and I see that he’s not hurting her at all; he’s tickling her ribs.

“Where’s that bone? Where’s that funny bone?” he says, suddenly playful, and I think I misconstrued the whole scene, until I look at Aaron and Mrs. Peterson, who are sharing a look I can’t quite understand. It’s solemn, though, nothing like the exchange Mr. Peterson is having with Mya as he throws her over his shoulder and begins to spin her around.

“Let’s go,” Aaron says to me under his breath, and I don’t argue.

Once we’re outside, we don’t say a word until we’re at least three blocks from our street and halfway to the train tracks on the other side of the woods that border Raven Brooks. The rain from earlier has stopped, but the ground still squishes when we walk.

“Where’re we going?” I ask Aaron when I feel like it’s okay to ask him anything at all.

“You’ll see,” he says, but doesn’t look at me. “There’s something I want to show you.”