The factory should be fenced off. Maybe it was at some point, but it sure isn’t now. And we shouldn’t be able to walk right through the front door, but we do.

“I used to love Golden Apples,” Aaron says, and his eyes get all dreamy.

I wait for an explanation, but all I get is a look of shock.

“You’ve never had Golden Apples?”

“I’m going to need you to stop saying ‘Golden Apples,’” I say. “It sounds like something my grandma would make me eat.”

I shake a crooked finger at him and try on my best old granny voice: “Eat your Golden Apples so you grow up big and strong, deary.”

“These wouldn’t make anyone big or strong. They were candy,” Aaron says. “I don’t know what they put in those things, but I wouldn’t sleep for days after I ate one.”

“Guess that explains why they stopped making them,” I say, but Aaron doesn’t respond. He just looks away.

The old Golden Apple factory doesn’t look like much. I mean, it’s an abandoned factory in the middle of the woods that miraculously only we seem to know about, so that’s pretty cool. But besides the still-operational conveyor belt and overall creepy atmosphere that comes from any abandoned place, I can’t figure out why Aaron was so stoked to show me the factory. It’s virtually empty, and I’m starving. Plus, my parents would have been so happy that I’ve made a friend, they probably would have fallen all over themselves to feed us. Dad would have busted out the Suzy Q’s for sure.

Maybe Aaron just wanted to get away from his house; I know I did—away from his dad, anyway.

“C’mon,” Aaron says, waving me up a ramp and toward a back door with an unlit EXIT sign over it.

It’s not an exit, though. Instead, the door leads to a hallway filled with more doors to the left and the right, each with at least two locks bolting them shut. A lockpick’s dream.

“Whoa,” I breathe, and Aaron nods.

“Each one leads to another door, too,” he says. “All locked.”

I stare at the corridor like we’ve uncovered a secret stash of Golden Apples.

“I’ve only made it through half of them. They’ve all got different brands of latches and padlocks. Here, I’ll show you my favorite room.”

Aaron beckons me to the middle of the corridor and fishes his tools from his pocket. Like me, he always carries his case. I hardly know what my pocket feels like anymore without it.

With his signature smoothness, he springs the first lock easily—a simple lever handle lock with a clutch. The door opens to a musty-smelling office, its furniture still haunting the room, waiting for its occupant to return. It’s windowless, and the light switch doesn’t work.

“None of ’em work,” Aaron says. “I think the conveyor belt runs on an old generator or something.”

In answer to our need, Aaron scoops up a heavy old flashlight from the top of a nearby filing cabinet.

“Found this baby on the first day,” he says, illuminating his face from under his chin like he’s about to tell me a ghost story. Then he twitches his eyebrows up and down. “Follow me.”

I hear scurrying against the walls, and I know it’s rats. I mean, it was a candy factory. I just pray to the Giant Aliens they keep to the walls and vents.

“What?” Aaron asks, his voice taunting. “You have a thing about rats?”

“I have a thing about rabies,” I say.

“Hold this,” Aaron says, handing me the flashlight. Then he fishes out a hook pick and leans his ear against the door. This is when I know Aaron is really at work; it’s like he’s listening to the door’s heartbeat. I don’t even bother asking why he locks the doors after he’s sprung them open. It’s because each time is like the first time, and there’s no feeling like that.

With the tiniest flick of his wrist, the pin clinks, and the door groans open.

Inside is a treasure trove of broken machinery.

“I had a feeling you’d want to see this,” he says, and I hardly know what to say.

There’s this cartoon that I used to watch (okay, that I maybe, possibly still watch) with a ridiculously rich duck. He has so much money that he keeps all his gold and jewels and coins and bills piled in a room-sized vault, and he swims through the treasure like it’s water. That’s what I wanted to do when Aaron opened this door.

The secret office behind the regular office was probably considered a junk room, a kind of elephants’ graveyard where electronics journeyed to eventually die as new hardware was invented to replace them. Maybe the tech guy at the Golden Apple Corporation figured he could make a buck selling those old monitors or keyboards or security cameras for parts. But the factory shut down, and the already-useless machines slept behind a locked door, guarded by an empty chair and another locked door.

“Dude, say something so I know you’re not having a stroke or something.”

“You smell like rat poop,” I say, because it’s the only way I can tell him no one has ever trusted me with treasure.

“Yeah. You’re gonna want to scrape your shoes before you get home,” he says, and I think he understands that “thank you” would be embarrassing.

I take what I can carry: the motor from an old vacuum, the fan from a CPU, a keyboard, and about five extension cords.

“I’ll bring a bag next time,” I say to Aaron, but he’s already walking ahead of me, out the hallway and back onto the factory floor. He locks the door behind him so no one else can get in easily and vandalize our secret place. Before I know it, we’re tromping over the wooded path that leads into the trees and away from the train tracks. Then he pauses, and I turn to see what it is he’s staring at.

There, just over the tree line, is a red-and-gold seat, rocking and creaking on a mild breeze, attached to the top of a large metal arc.

“Is that a Ferris wheel?” I ask, already pushing past Aaron to cut a path through the overgrowth.

I’m expecting to find a clearing full of other confection-colored rides and ticket booths—one of the millions of county fairs that pop up on Main Streets or in open parking lots during the summer months—but what I find instead is a ghost town.

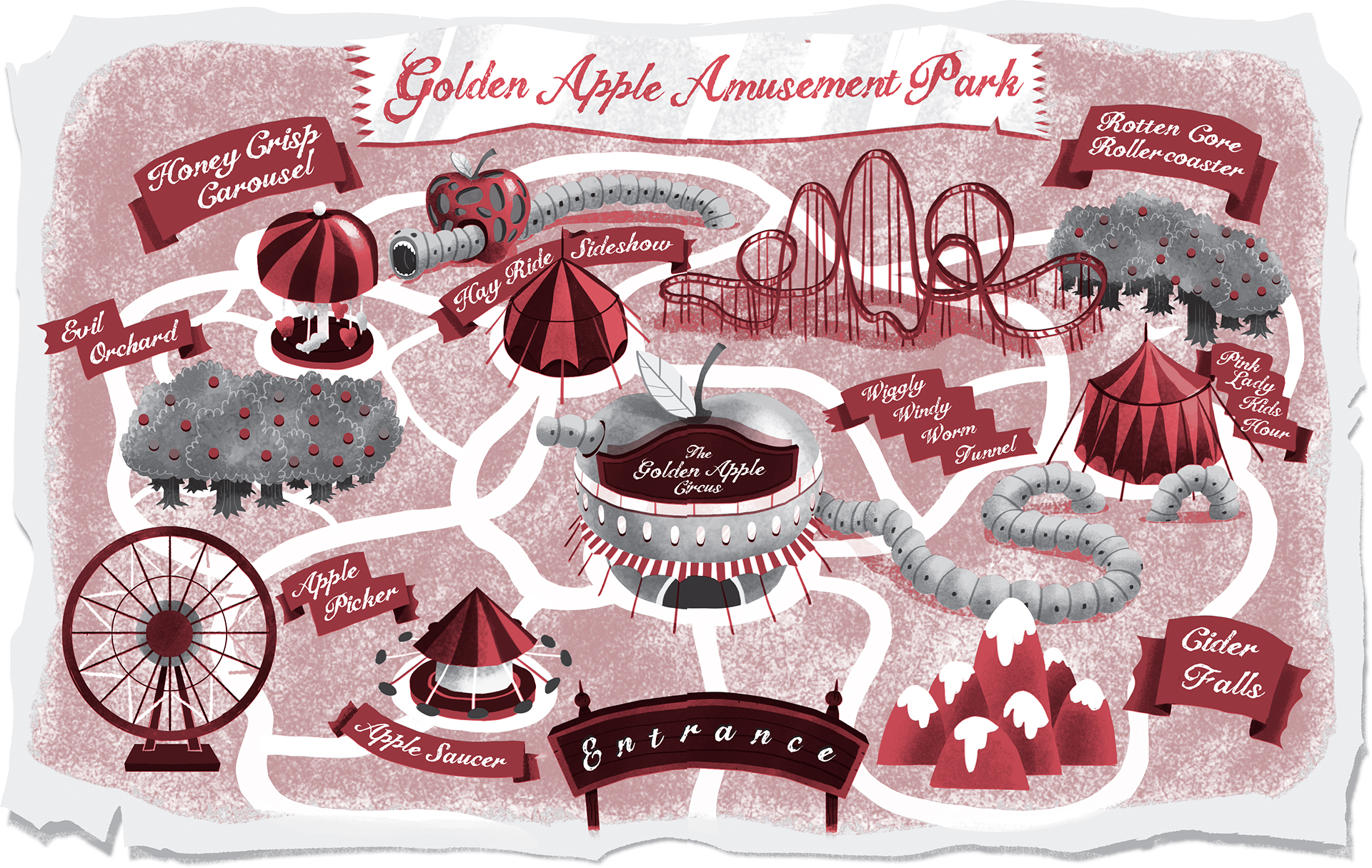

The Ferris wheel cars are paralyzed, moved only by the warm breeze that blows by. The wheel itself is covered in so much graffiti, I can’t even tell what color it used to be. And not the cool kind of graffiti that’s left by daredevil street artists. The ugly kind of graffiti that’s meant to erase whatever’s underneath. I see the opening to a fun house that looks more horror than fun with its apple-shaped head and its wide mouth with bared teeth. I see a charred concession stand that’s missing its roof and a collapsed stage still encircled by tiered cement seats. There’s a carousel of vandalized animals prancing across a motionless grate. There’s the top curve of a roller coaster track cresting above the tree line, a lone car perched at the apex.

There used to be more—lots more. A directory obscured in oily burn residue tells me at least that much. But whatever this place was, it’s dead and buried now.

Across the concession stand—in faded white letters over red paint—reads GOLDEN APPLE AMUSEMENT PARK.

“They made a park, too?” I ask, incredulous that Aaron didn’t show me this just as eagerly as the factory. Sure, there were no locks or machines, but there is plenty to mess with between the Ferris wheel and the roller coaster. I mean, the cars have to be around somewhere.

“I bet I could get the carousel going again,” I say, stacking my factory treasures against a tree and racing across the overgrown park.

I emerge from the brush to find him looking at the ground, his hands crossed over his chest. He’s acting like he’s mad at me.

“What’s the matter?”

“Nothing, I just don’t like it here,” he says evasively.

“Are you joking? What’s not to like? Seriously, why is this place, like, completely hidden?”

“It’s not hidden,” Aaron says, but he almost spits it out, like he’s disgusted with me.

“Ooookay,” I say, clearly terrible at sidestepping whatever land mine is buried under all this ash.

Ash. Like maybe it burned down.

“Did something … what happened here?” I ask, and Aaron looks up. His eyes look like they’re ready to shoot lasers, and I’m close enough that I think he actually might throw a punch at me, but I still have no idea why.

Then he seems to catch himself and his shoulders relax a little. “I shouldn’t have come this way. I forgot this was here.”

But I don’t think that’s true. I think maybe he wanted me to see it.

“So did it, like, burn down or something?” I prod.

Aaron just stares at me.

“I lived down the street from a house that burned down once,” I say, starting to ramble. “It was a space heater or something, and everyone got out okay, but the house was completely torched, just like this … place … looks …”

I keep waiting for Aaron to say something—to save me from my babbling—but he keeps staring. The sudden silence is a stark contrast from the factory only moments ago. Just when I think we’re going to suffocate under all that awkwardness, Aaron shakes his head.

“Let’s get out of here,” he says, and even though I’m relieved to go, I know I’ve let Aaron down somehow. He doesn’t say a word the rest of the way home, just a casual “See ya around” before he steps onto his unlit porch and disappears into his house.

I replay the night in my head. The house with all its twists and turns. His dad’s … unique sense of humor. The factory. The amusement park. I try to figure out when things turned weird. Aaron was squirmy after we left his house, but that seemed to wear off once he showed me the factory. It was only after we got to the burnt remains of the amusement park that Aaron’s entire demeanor changed. The guy who shared his trove of abandoned electronics had disappeared, and the angry, scared kid he’d left in his place needed me to know something.

“What were you trying to tell me, you weirdo?” I ask Aaron’s dark porch, because I know what it’s like to want someone to guess how you’re feeling. It’s way easier than saying it.

I set my electronics haul beside the door and decide I’ll leave it there until the morning. Maybe by then I’ll have a plausible explanation for where they came from. I barely have time to close the front door before Mom and Dad pounce on me.

“Did you have fun?”

“What’s he like?”

“Are you in the same grade?”

“Have you had dinner yet?”

“Yeah, he’s okay. Same grade,” I say. Then I shrug. “Not hungry.”

Mom’s palm cups my forehead. “You coming down with something?”

“I just don’t feel like eating, okay?”

Mom and Dad exchange a look.

“He looks like our son,” Dad says, “but …”

He reaches for my face, tilting my chin to see up my nose, pinching my cheeks to open my mouth.

“I don’t know, Lu. He could be a changeling.”

“Hardy har har,” I say, swatting Dad’s hand away.

“Well, you have two choices,” Mom says. “You can stay here and eat like a normal twelve-year-old or you can run a boring errand with your boring mother.”

I hadn’t noticed before that she’s wearing her rain jacket and shoes.

“I need a book from my office,” she says.

A book. From her office at the university.

“Your office is near the campus library, right?”

Mom cocks her head to the side. “Just the science library.”

“But does it have newspapers? Like, old records?”

Mom looks like she wants to ask another question, then loses interest. “Probably,” she says, grabbing her car keys.

* * *

Our shoes squeak against the orange-and-white linoleum of the Life Sciences building on the east end of campus. The university is old, and some of the original buildings are really pretty, all brick and dark wood and pillars. The east end of the grounds, though, was built sometime in the sixties, and I’m pretty sure that was the last time anyone’s touched it. That’s one of the reasons the school is so excited about having Mom on the faculty. She’s a chemist, and not just any chemist. She’s written a couple of papers on some experiment she did that got published in some hoity-toity journals, and now people know that Luanne Roth is super smart. Smart scientists mean more student enrollment, which means maybe the school will finally be able to buy some new equipment and remodel the bathrooms. Or so Dad says.

“Which way is the library?” I ask Mom.

“Downstairs, to the left, but, Narf, I’m only going to be a min—”

“Meet me down there!” I call over my shoulder, disappearing down the stairs and around the dark hallway before she can tell me no.

The science library is smaller than most elementary school libraries, which makes it easy to find the periodical section. Most of the tables are piled with neatly stacked science journals, well worn with sticky covers and dog-eared pages. Those aren’t going to help me, though.

I keep scanning the periodical shelf until finally, in the very bottom corner, I spy a pile of old newspapers, the masthead on one I recognize from the sign on the building where Dad works: The Raven Brooks Banner.

I sit on the ground and pull the stack onto my lap, skimming through the headlines as quickly as I can for anything with the words “Golden” and “Apple.” I’m a third of the way through the stack when I hear footsteps echoing through the hall above. I recognize my mom’s urgent stride. Even when she’s not in a hurry, she moves fast.

“Come on,” I mutter, flipping faster through the pile, but nothing is jumping out at me. I skip to the bottom of the stack, but in my hurry, I fumble the papers and send the collection scattering.

“Narf, are you making a mess down there?”

I hear my mom’s footsteps begin to descend the stairs. Ready to admit defeat, I start scooping the stack back together when I spy a paper with bold letters spelling out the headline.

I grab the paper and try to skim what I can, but Mom is almost at the bottom of the stairs. So I commit a mortal sin.

“Aliens, forgive me.”

Tearing the newsprint, I pull the page from the paper and shove it into my pocket before my mom pokes her head around the corner.

“What were you trying to do, build a nest?” Mom asks, her hand massaging the back of her neck.

“I didn’t tear anything!”

I am, without a doubt, the world’s worst criminal.

Mom knows it, too. She shakes her head at me, then helps me clean my mess before we leave the library mostly the way we found it.

At home, I wait until I can hear my parents snoring before pulling the article from my pocket.

On this day exactly one year ago, life for the Yi family changed forever, and the town of Raven Brooks lost a piece of its heart. What should have been a day of family fun at the newly opened Golden Apple Amusement Park turned to unimaginable tragedy when a mechanical flaw in the park’s much-buzzed-about “Rotten Core” roller coaster caused the death of seven-year-old Lucy Yi.

A close-up picture of a smiling girl stares back at me from the page, her eyes sparkling under a fringe of dark bangs. I read the caption reluctantly:

Lucy Yi was a first grader at Raven Brooks Elementary School.

She was a first grader, I think to myself. Was, because she’s dead now. Is that the something Aaron wanted me to guess? How could I ever have guessed something that horrific had happened right there in the same park where we were standing earlier tonight?

I keep reading.

“It was just so shocking. I mean, an amusement park is supposed to be a carefree place,” says Trina Bell, a former Golden Apple assembly line worker at the factory a mile from the park.

“I’ll tell you this—no kid of mine is going to set foot on one of those contraptions ever again. This just goes to show you never really know what’s safe,” says Bill Markson as he sweeps the sidewalk in front of the Pup ’N’ Puss Pet Supply. “You know what I think? I think they rushed to open before they’d done all those safety tests they should have done.”

Yet not all of Raven Brooks blames the Golden Apple Corporation or the builders responsible for its construction. Gladys Ewing tries to hold on to the happy memories despite the long shadow cast by the confection maker’s meteoric fall from popularity.

“I will never forget riding the Ferris wheel with my youngest son on opening day. I’ve never seen him smile that big. People ought to be ashamed of burning that place down like they did.”

I read Gladys Ewing’s quote three more times to make sure I’ve read it right.

“They burned it down?” I breathe.

In a week dominated by suffering for a family and reflection on the further tragedy that could have struck, angry parents and townspeople gathered at the shuttered Golden Apple Amusement Park to grieve together. But what was meant to be a candlelight vigil turned riotous when several disgruntled citizens turned their anger toward the park. By then, blame for young Lucy Yi’s death had fallen to the Golden Apple Corporation and the amusement park’s lead—

I flip the page over, but all I find are stories of the neighboring town’s zoo and a sale on organic chickens at the natural grocer (when they were still selling meat, I suppose). I turn back to the article and see that the story continues on page B3.

I lay the crumpled newsprint at my feet and lean against the bed, my head all the way back as I stare up at the ceiling. So that’s what Aaron couldn’t find a way to tell me, not that I can blame him. How do you bring up something that awful in casual conversation?

As awful as the history of that place is, that isn’t what’s eating at me, either. What I can’t figure out is why Aaron brought me there in the first place. He obviously wanted me to know what had happened there.

But why?

I fall asleep with thoughts of Aaron and his family whirling through my brain.

Mrs. Peterson’s trembling hands as she puffed away on a cigarette by the window. The look she exchanged with Aaron when his dad talked about removing bones. The way Mya’s face lost all its color just before her dad picked her up and tickled her ribs.

That night, I dream of small, fragile skeletons crouched low to the ashy ground, bounding around a darkened Ferris wheel that’s being slowly choked to death by vines.