I throw a pair of pajamas into my backpack and forgo my toothbrush to make space for the audio manipulator. It’s built, and all we need now is to add the prerecorded audio. I survey my bag’s contents and decide that pretty much covers all I’ll need.

Downstairs, as I slip on my shoes, Dad and Mom watch me a little too closely.

“Excited for your big sleepover?” Dad asks.

“Dad,” I say, wincing.

“Sorry, your super grown-up, totally not-a-big-deal hangout where you might wear pajamas and might not sleep.”

“That’s not better,” I say.

“Just remember to brush your teeth,” Mom says, and I swear to the Aliens she can see straight through my backpack to my missing toothbrush.

“Uh-huh.”

“And say thank you,” she says. She’s still irked that the Petersons haven’t bothered to come by, but to her, “please” and “thank you” are holy words.

“I will,” I say.

“And solve the mysteries of the universe,” Dad says, and Mom gives him a look.

“What?”

“Are you implying that manners and hygiene are impossible requests of our son?”

“Lu, he’s twelve. He’s barely human at this age.”

I decide to end things before they get ugly. “I’ll say thank you,” I tell my mom, and she smiles like she’s won. “And I’ll ponder the meaning of life,” I tell Dad, and he gives me a dorky thumbs-up.

As I cross the street, I do ponder, but not about life’s meaning. I wonder how in the world I’m going to ask Aaron about everything I read in the old newspapers about Golden Apple Amusement Park, about his dad and Mya. Because there’s not even a sliver of a chance that I’ll be able to stop myself from asking.

* * *

Mrs. Peterson glides into the room like she’s on wheels. I don’t even hear her until she’s right behind me, a pile of sheets stacked on top of a pillow cradled in her arms. I don’t mean to jump; it’s just that she surprised me.

“Wow. I know I forgot to put on lipstick today, but exactly how frightening do I look?”

“No, you don’t at all. I mean, I just—”

“Nicky, I’m kidding, honey. I have a light step.”

“Mom’s a teacher, but she danced ballet when she was in college,” Mya says as she plunks down on Aaron’s bottom bunk. “She even danced at one of Dad’s park openings.”

“No one invited you, Pariah,” Aaron says, nudging Mya off his bed.

“Thank you, Mrs. Peterson,” I say, taking the linens from her.

“Hmmm?” she says, her eyes glazed over like she’s distracted. “Oh, you can call me Diane, honey,” she says, focusing on me long enough to lightly tousle my hair.

“I said stop calling me that,” Mya says, shoving Aaron’s leg when he pokes her with his toe. “Ow! Your toenails are like knives!”

“Mya Pariah eats farts and papaya,” Aaron sings, still poking her.

“Mom!”

Mrs. Peterson—Diane—spreads the sheets across the bottom bunk of Aaron’s bed.

“Stop calling your sister a pariah,” she says, clearly lost in more pleasant thoughts. She’s humming quietly to herself, somehow blocking out the escalating brawl between Aaron and his sister.

“So if you eat farts, does that mean you burp farts, too? Is that why you always smell so bad?”

Mya flushes pink and glances at me.

“I do not smell bad! Mom!”

But Diane is already on her way out the door. She’s moving slowly, though, almost like she’s forgotten where the door is. All at once, Aaron and Mya stop arguing, and a sudden silence blankets the room. In that quiet, I can hear the faint song Mrs. Peterson has been humming to herself. Only now, she’s practically whispering it, like she’s afraid to scare away the memory attached to the tune.

Mya follows her, still glowing crimson, but she lands a final solid punch on Aaron’s bicep on her way out. I watch her leave. Ever since I saw the photo of her, Lucy, and that other girl wearing the golden apple bracelet in the newspaper article, I’ve been trying to understand what it would mean that the bracelet would find its way into my front yard. I still don’t know, but I have a feeling Mya does, which means I’ll probably never figure it out. Mya’s even less of a sharer than Aaron, if that’s possible.

As soon as Mya reaches the stairs at the end of the hall, Aaron closes the bedroom door and waves me to his desk.

He pulls a drawer open, and rather than take anything out of it, he reaches his hand all the way inside until he’s shoulder-deep and still reaching. I look at his desk, and it doesn’t take me long to determine that what I’m seeing is impossible. Flush against the wall, his desk can’t stick out more than a foot and a half.

“What the—?”

Aaron smiles as he struggles to grip whatever hides in his magical desk. Then he gives up and pulls the whole drawer out, exposing its missing back.

We duck down, our heads together, and I understand. There’s a hole in his wall. The drawer has a false back.

“You really are a criminal mastermind,” I say, and Aaron chuckles. Then he hauls out his treasure.

It’s a box full of junk of the very best kind: There’re dismantled motors and remote-control cars, parts of an old toaster, some speaker wire, clamps and locks, keys to nowhere, a discarded keyboard, a phone without its faceplate, and at least three broken calculators.

It’s a gadget head’s bounty.

“Holy Aliens, Aaron,” I say, and he smiles in a way that I haven’t seen. I think this is what pride looks like on Aaron. From one weirdo to another, I know how elusive pride can be.

“It’s all stuff I collected from the factory before you moved here. I wanted to make something out of it, except I don’t know how.” He looks at me. “Think you can use any of the parts for your audio synthesizer?”

“The synthesizer!” I can’t believe I almost forgot. Reaching for my bag, I pull out the finished product, and as quickly as Aaron’s face lights up, it dims again, and I realize that maybe he wanted to help me finish it.

“It’s not ready yet,” I hurry to explain, and some of the light returns to Aaron’s face.

“No?”

I shake my head slowly and explain. “We still need the recording.”

He smiles so wide, I think his face might split apart.

An hour later, stuffed on Surviva bars and bloated to the point of bursting, Aaron and I are a mess. I’m laughing so hard, I can barely hold the microphone to the, er, audio source. Every time Aaron lets one rip, we fall apart, rolling across his floor like beetles on our backs.

It takes everything in me to gather myself, and I plaster on my most serious face, placing a hand on Aaron’s shoulder.

“Fine, sir,” I say. “I daresay that was your best work yet.”

He matches my seriousness, but only for a second, and then we both break.

“Boys,” Mrs. Peterson says, peeking in the doorway. “Are you planning to come down for pizza at any point tonight or—sweet Mary, what is that smell?”

I laugh so hard my sides pinch. Aaron swipes the tears from his eyes.

“Sorry, Mom,” he says. “We’re, uh—”

“Performing an experiment,” I say.

“Creating art,” he says over me. Then we bust up all over again.

“Well, whatever you’re doing, open a window, for Pete’s sake,” Mrs. Peterson says. “That’s toxic.”

Aaron farts, this time accidentally, and I have to bury my face in the bottom bunk to keep myself from laughing to death—or suffocating. Either one is equally plausible.

Once we’ve calmed down enough to choose a series of Aaron’s choicest farts for the synthesizer, we’re suddenly at a loss for things to do. It’s late, but neither of us is tired. Still, maybe out of habit or boredom, we pull on pajamas and take to our bunks, Aaron on the top bunk, me staring at the slats from the bottom.

It’s not the right time, because no time is the right time, but somehow it seems more possible to talk to Aaron about his dad when I only have to stare at the mattress above me and not at his face.

“So, I gotta ask,” I say, trying to sound casual.

“No, I don’t believe in aliens,” Aaron says.

“Wait, what?”

“Sorry, man. I know it’s your … I dunno, religion or whatever,” he says.

“It’s not my religion.” Then I catch myself. Pushing my shock aside (seriously, how can he not believe in aliens?—the proof is overwhelming), I try again to bring up the most awkward conversation ever.

“So, what’s up with your dad anyway?”

The silence that follows is painful. I only have myself to blame; it was perhaps history’s worst segue.

“What do you mean?” Aaron asks, but he’s quiet, and his voice doesn’t ask, What do you mean? as much as, How much do you know?

“I mean, he’s pretty … intense …” I say. This is excruciating. At this rate, it’s going to take me a week to work up the courage to ask him what I really want to ask him—if Aaron knows his dad is suspected of purposely making rides unsafe. Ugh, even thinking it sounds absurd. Still, I can’t shake the feeling he wants me to ask him. Why else would he “accidentally” bring me by Golden Apple Amusement Park?

Aaron shifts in his bunk overhead, and I hold as still as I can so I don’t miss a word.

“Just ask me what you want to ask me,” he says, and suddenly he does sound tired. He sounds like he hasn’t slept in years. It’s the old Aaron again, the one I encountered on our first few times hanging out. He’s old beyond his years, burdened by something unseen.

I’ve aged him. I weighed him down by bringing up the past—a past he has to know about. Of course he has to know about it.

“Why did you want me to know about the park?” I ask, and he’s quiet for so long, I think maybe he’s decided to stop talking to me for the rest of the night.

Then, after a long while, he says, “He was a genius, you know. Like, a real, Einstein-level genius.”

I don’t say anything because I do know that. And I don’t want to stop him talking now that he’s finally started up again.

“I’m not happy Lucy Yi died,” he says, and this takes me off guard because of course he’s not. Who would ever be happy about something like that? Then I remember something else he said to me in this very room, something he said like a confession, even though I didn’t know it at the time.

What does make a person bad, then?

Being happy when bad things happen.

“But he stopped after that,” Aaron said, and I understand now.

The accident that killed Lucy also killed Mr. Peterson’s career, a career that was becoming increasingly reckless with every new venture.

Then Aaron really does stop talking. Before long, I hear the slow, even breath of his slumber above me. The weight on him has disappeared, at least for now. But it isn’t actually gone. The weight has shifted to me, and I wonder how I’ll ever fall asleep like him.

I lie awake for what feels like an eternity, staring at the slats above my bunk, thinking about how long Aaron’s blamed himself for simply feeling relieved.

Relief in the form of Lucy Yi’s death.

* * *

When I wake up, the only light in the room emanates from the recording light on the audio simulator. Aaron is still in the top bunk. His snoring is the only clear indication he’s even alive. I try to remember the last time I’ve slept that soundly.

Except he’s not exactly peaceful. He’s twitching—hard—and if I listen closely enough between bouts of snoring, I can hear him begging to the things of his nightmares—“no” and “don’t” and “please.”

I lie there for a moment, trying to figure out what exactly it was that woke me up. I was dreaming again, but this dream didn’t start in the cart, or in the grocery store at all. This one started in a tunnel. It closed in on me, edging closer and closer to my shoulders and the top of my head until I began to sink. I dropped to the bottom of something deep and dark, so dark I wasn’t sure my eyes were even open. And while I don’t remember much after that, I do remember the voice that hissed to me across that deep, dark expanse. I remember the chilling words it whispered to me:

Find me.

And then I woke up. But it wasn’t the voice from my dream that woke me. It was a sound.

But like the voice from my dream, the sound that woke me is long gone, and in its place is thirst.

Between the Surviva bars and the pizza we did eventually sneak downstairs to eat, my mouth is a desert, and as I stare at the bunk above me where Aaron twitches away, I know there’s no way I’m going back to sleep until I can get something to drink.

Snatching a flashlight from the pile of orphaned electronics on Aaron’s floor, I creep down the hall, taking care to avoid as many squeaky floorboards as I can, but Aaron’s house is full of them. Mya’s door is shut tight, but Mr. and Mrs. Peterson’s door stands open a crack, and I can barely make out the rustle of sheets as I sneak by.

Just find the kitchen, get a drink, and go back to bed, I tell myself. There’s something weird about sneaking around your friend’s house when everyone else is asleep. When you’re awake, you’re a guest. But when the rest of the house sleeps, it’s hard not to feel like an intruder.

The thought of Mr. Peterson mistaking me for a home invader is enough to propel me down the stairs, and even though I know I made too much noise, at least I’m past the worst part now that I’m downstairs.

Except I’m not past the worst part because suddenly I’m lost. I hold the flashlight up, disbelieving that I could actually have lost my way from the stairs to the kitchen. But I really have. The doorway to the kitchen should be right in front of me, shouldn’t it? I walk forward, not believing what the flashlight is showing me. Yet there it is, a wall where there should be a kitchen. I look to my right, but the living room isn’t there, either. In fact, all that’s in front of me is a long hallway.

I stop cold, the contents of my anxious thoughts creeping into my waking life. I shake it off, though, and remind myself that I’m just tired and thirsty, and I haven’t ever seen this house at night. It’s kind of a maze even in the daytime, so I must have taken a wrong turn somewhere between the upstairs hallway and the stairs leading here.

I keep walking, still hopeful that I’ll find the kitchen just a little farther ahead. I don’t, though. Instead, I find myself surrounded by closed doors, each boasting a slightly different doorknob and keyhole.

“What—?”

I’m just about to turn around and retrace my steps back up the stairs when I hear a sound I’d hoped to never hear again from this house—ice-cream-truck music.

The melody winds up, then down again, then goes silent and repeats the pattern. I step lightly across the floor of the hallway, pressing my ear against each door I pass. Yet none of them seems to hide the source of the sound.

Then the music stops. I wait to see if it returns, but all that greets me are the creaks and groans of someone else’s home. I’ve lived in enough houses that belong to other people to not be freaked out by those sounds. Still, there was something about that—

Thud.

I stop cold. Straining, I wait to hear it again. I don’t have to wait long.

Thud.

This time closer. This time with a dragging sound that follows. Then another thud.

There’s no mistaking the sound now. It’s footsteps. Footsteps that aren’t moving quite right.

I swallow, but I can’t wet my dry throat. I want to turn around and go back up the stairs, but now I’m not entirely certain the sound was coming from up ahead. The hallway is playing tricks on my ears, and the thudding and dragging now sounds like maybe it’s coming from behind me.

A groggy Mr. Peterson creeping up behind what he thinks is an intruder.

A sleepwalking Aaron fumbling through his house.

An actual intruder.

None of the possibilities slow my thumping heart, and why didn’t I just get some water from the bathroom upstairs?

The thudding and dragging speed up, and all at once, I understand why it’s getting louder: It’s moving toward me.

I turn to open the door behind me, no longer trying to figure out where the sound is coming from. All I can think of is hiding until it passes. But the doorknob won’t budge. I try one farther down the hall, but it’s locked, too. The thudding is louder still, and I try another door. Mercifully, this one opens, and I fall through it, closing the door behind me a little too hard. I wince at the sound, then wait to see if the footsteps pass.

Suddenly, I don’t hear them anymore. I press my ear to the door, but it’s as though there was never any noise in the first place. No music. No footsteps. No creaks or groans in the walls or pipes.

My flashlight is trained to a single spot on the floor, and only now do I realize I’m standing on a well-worn area rug—the kind you’d find in the sitting room of some rich old lady’s house. Like maybe it was nice a long time ago, but now it just looks like it’s trying to hide something worse underneath.

I swing my flashlight across the room and find it cluttered with so much furniture, I can hardly see the walls that frame the space. There are bureaus and bookshelves, glass cases protecting plaques framed in wood and statuettes carved from crystal. I move closer and see Mr. Peterson’s name etched into every single one, each praising him for a different accomplishment.

One of the glass cases abuts a massive wooden desk that takes up a fourth of the room, and so much paperwork clutters the desk, even the imposing piece of furniture looks like it might buckle under the weight.

I train the light on the papers, spread haphazardly across the surface, trying to make sense of a room that at one time must have served as an office to Mr. Peterson.

There are large curled blueprints paperweighted at their corners, with measurements and precise notations penciled beside each line and curve. Some of the names I recognize from old newspaper articles: the Bell Tower, the Dead Weight, the Dragon’s Lair—the most dangerous thrill rides from Mr. Peterson’s parks across the world. There are some I don’t recognize: the Inverted Cyclone, the Whip—whose curves and lines cover the entire space of the blueprint.

There’s one blueprint that isn’t done, that doesn’t even have a name, but it spirals to the edges of the paper at angles that seem to defy gravity. A smattering of red Xs mark areas on the design like some kind of treasure map, only instead of signaling treasure, the Xs have words beside them like Access 1, Egress 2, and Hatch 3.

My mind is trying to keep up, but disorientation and fear have given way to exhaustion, and I’m distracted by the need for water and sleep.

I’ve just about resolved to ask Aaron about the room and the blueprints tomorrow morning when the beam of my flashlight lands on a filing cabinet shoved against the wall beside the desk. It’s packed so fully, the drawers are spilling out their contents, with one fat file seemingly dominating the drawer. In thick black marker, the file label reads Golden Apple Amusement Park.

My heartbeat quickens, and I grab for the file without thinking. Common sense should have made me rethink snooping in Mr. Peterson’s study, but I seem to have lost common sense as I lost my way in this winding house.

I try pulling the file from the drawer, but it’s wedged in too tightly. Instead, all I manage is to dislodge a couple of papers, sending another few fluttering to the floor to join an already growing pile of spilled contents.

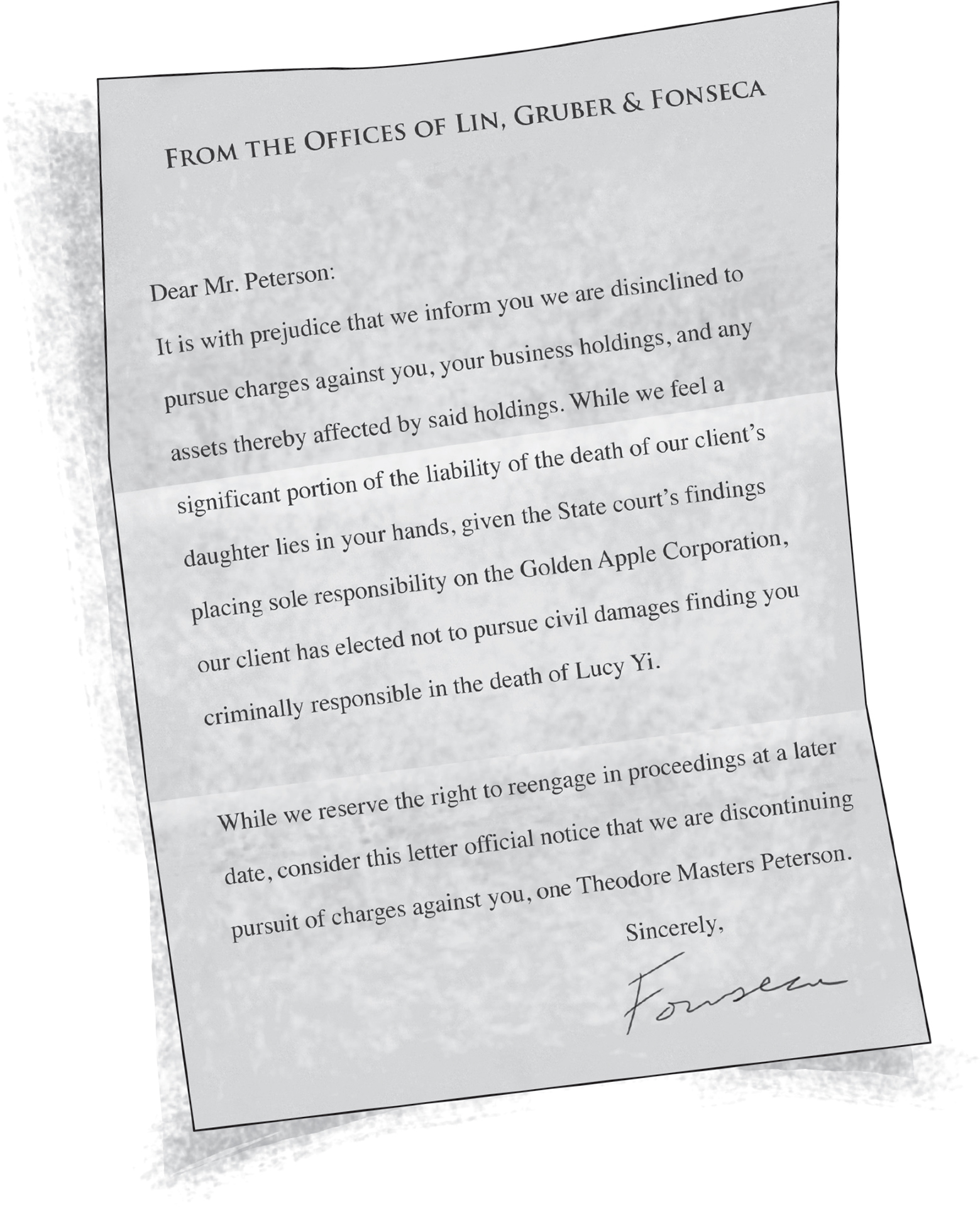

The first piece of paper is a letter printed on thick stationery, with the kind of letterhead that embosses the paper.

I blink at the letter and translate the legal jargon as best as I can. Their client’s daughter was Lucy Yi. It must have been Lucy’s parents suing Mr. Peterson for their daughter’s death. But the state found the Golden Apple Corporation responsible, not Mr. Peterson, which means Mr. Peterson probably would have been absolved in civil court, too. I picture my parents in that same situation, stone-faced in a courtroom while some faceless company is named as my killer. I wonder how it feels to hurt that badly, to not get an apology, to not be able to look anyone in the eye and say, “You’re the reason I don’t make jokes anymore or eat cake or go to parks because there are too many kids there who’ll remind me of the one I don’t have anymore.” I wonder how it feels to be robbed like that, again and again.

I wonder how it feels to know your dad was the real robber.

I accidentally step on the pile of papers I’ve contributed to on the floor. In the shadows of the study, they look like grainy photographs of a forest, a construction site, a group of people crowded around a worktable. But when I pick them up and lay them across the desk, the beam from my flashlight reveals something unexpected.

The first picture is a photocopy of a newspaper article:

Ground Breaks on Hometown Landmark: Construction Begins on Buzzed-About Golden Apple Amusement Park.

Below the headline is a thick grove of trees, a bulldozer, and a team of workers with chain saws ready to clear the land. Mr. Peterson is in the foreground, construction hat high on his head, mustache curled to match his smile. But in the background, nearly out of frame, is a stooped figure lurking by one of the trees. I likely wouldn’t have noticed him at all if not for the red ink encircling his figure, the pen retracing the circle so many times the page is torn.

I might not have noticed it at all, but now that I do, there’s no mistaking who it is. Blurry and marred in red ink, it’s Aaron. He’s younger—five years younger if it’s at the start of the construction—but it’s Aaron, and while he’s blurry, it’s hard to deny that his pose implies he’s hiding.

I push that page aside and find another photocopy of an article:

Ahead of Schedule! Pressure Mounts for Golden Apple Amusement Park to Open by Summer.

In this picture, Mr. Peterson points to a crane swinging a beam across the framework of what was to become the base of the fun house, judging by the gaping mouth surrounding the beginnings of a track. All eyes are on Mr. Peterson in the picture, including the crouched boy, circled in red, peeking out from the fun house framing.

The next article is dominated by an entire crew of men in vests and hard hats staring upward at a structure so tall, it doesn’t fit in the frame, which makes it more noticeable that one head stares straight ahead, or rather at Mr. Peterson standing at the front of the group. Aaron is once again encircled in red ink, hanging back by a pile of iron rods.

Page after page shows Aaron nearly out of frame, ousted from his hiding place by the red pen’s wielder. I look around at the rest of the office, its hulking furniture casting distorted shadows across the framed pictures of the Peterson family. It strikes me that this is the only room in the entire house where I’ve seen any family photos at all. But when I examine the pictures closer, I see that they’ve also been marred by red ink. The placid, smiling faces of Mrs. Peterson and Mya grace most of the pictures, as does Mr. Peterson’s. The only unsmiling face is Aaron’s.

And as the Peterson family ages, their smiles turn from placid to pinched, and Aaron’s face disappears altogether behind the scribble of that angry red pen. Only one picture offers more than a scribble—what appears to be the last family portrait taken of the Petersons, judging by their ages. Beside the etched-away face of Aaron is what I first read as his name. But when I look closer, I see that the word isn’t “AARON.”

It’s “OMEN.”

I drop the flashlight and the room goes black. I stand in place, trembling on a squeaky floorboard it’s too late to avoid. Then, from somewhere in the dark, I hear the slow creak of a door swinging open.

I was so engrossed in the pictures, I didn’t even hear the footsteps return.

The thump, the drag, the labored movement of whatever has emerged into the room, is so close that I can hear breathing I know isn’t mine.

Run. Run!

But my stupid feet are stuck.

I want to be dreaming. Please let me be dreaming.

But I’m not. I know I’m not.

The breathing grows louder, like an animal preparing to pounce. I hold perfectly still, my only defense in the pitch-black of the room. But whoever is here knows I’m here. Floorboards moan under the weight of feet that methodically make their way toward me. They step to the glass case, rattling the awards on their shelves. They step to the desk, with its papers exposed to my prying eyes. They step to the filing cabinet, its papers still protruding from the drawer.

They step so close to me that I can feel that hot, menacing breath on the back of my neck. In its exhale, I hear my name.

“Nicholas,” the voice says. “You shouldn’t be here.”

A soft glow illuminates the floor and the flashlight at my feet. Looming over me is an impossibly long shadow.

I turn because I don’t know what else to do. I can’t run. I can’t hide. All I can do is face the shadow.

Heat hits my face and temporarily blinds me, and when my eyesight returns, the first thing I make out is argyle.

I tilt my head to reach the top of Mr. Peterson’s face, and I don’t like what I see. His eyes, darkened and distorted by the flame of the candle he holds, are barely visible. Below his eyes are the flaring nostrils of a man whose house I should not be wandering without permission, whose private office I should absolutely not be rummaging through. His thick mustache curls upward mockingly, belying the frown that’s only barely visible underneath.

I look down at my bare feet again, terrified and embarrassed, which is the only reason I notice that Mr. Peterson’s shoes are on.

In the middle of the night.

I look up again, taking in his pants and his argyle sweater. I’m in my pajamas, but Mr. Peterson is fully clothed.

I struggle for answers to questions I think he might ask, but he doesn’t ask anything. In fact, he hasn’t said another word since I turned around to face him. He’s just … staring.

I watch the light from his candle flicker and sway in the draft of the house, but Mr. Peterson holds it perfectly still. That’s how I notice his hands, smeared and coated in something thick and dark.

My eyes travel upward, and I don’t know if I’m expecting an explanation for why he’s here, what’s on his hands, why he’s up so late—or if he’s expecting an explanation from me—but what I’m not expecting is that smile. That horrible, out-of-place, unhappy smile that’s suddenly crept out from under his mustache and spread across his face.

Then he starts to laugh. It’s a low rumble from his gut at first, but soon it travels through his chest and his throat and out of his mouth, and the light, airy giggle is so vastly different from the growl it started as, I am all at once aware of how much of the room he takes up. His shoulders are broad enough to equal twice my width. I can barely see the doorway behind him.

And all I want is that doorway.

Then, as suddenly as his horrifying laughter started, it stops, and he holds the silence between us with a grasp as tight as that on his candle. He leans down, inches from my face, and meets my eyes.

“Nighty night, Nicky,” he says, and with a single puff, he blows out the candle and steps aside.

I sprint out of the room and find the stairs, running on feet I can’t even feel anymore. I run past the hallway I was so desperate to traverse quietly moments ago. In Aaron’s room, I swing the door shut behind me, locking it against what lurks in the darkness. I look to the top bunk where Aaron sleeps, certain the commotion woke him, but he doesn’t even snore anymore. He lies still, his face obscured by the comforter, and I wait for a second to see if he’s actually awake behind there.

When only silence greets me, I’m left with the sound of my heart pounding away in my ears, my teeth chattering in violent rhythm as I fight to calm myself. Then, once I’m finally still, I prop my pillow against the wall and watch the door from the bottom bunk, flinching every time the wood of the old house pops or settles.

I’ve forgotten the drawer full of possibilities.

I’ve forgotten the water I never drank.

I’ve forgotten the excitement I had about finally making a friend as strange as me.

All I remember is the music in the basement. Photo after photo of Aaron’s circled image. The grime on Mr. Peterson’s hands.

And that mad, mad smile that grew from a face that’s forgotten joy.