I throw my gray hoodie on over my backpack, but I should have known Dad would see it anyway.

“Getting a head start on studying, Narf?” he says, flicking a finger toward my hunchback.

“Never too early,” I say, then shrug. It’s the best antidote to his inquiries, a vague response with a shrug. He shakes his head and goes back to whisking whatever is bubbling on the stove. I can barely see the top of Mom’s head under all the steam emanating from dinner. She doesn’t seem to notice, though. She’s onto something.

“Be safe,” she says without looking up, before she knows where I’m going.

“Going to Aaron’s,” I say, even though I think I could have gotten away with saying nothing at all.

“You’re spending an awful lot of time over there,” Dad says, whisking so hard he’s doing a little dance from the hips down. “Whatever happened to Miguel’s son, Enzo?”

“The Petersons don’t mind,” I say, avoiding the topic of Enzo altogether.

“Lu, we really should have them over,” he says, but Mom raises her hand to stop him, still not looking up from whatever formula has her rapt attention.

“Seven weeks,” she says, like we’re supposed to know what she means.

Miraculously, Dad does know what she means. “Honey, come on.”

“Nope,” she says, and we all know it’s the end of the conversation. Whatever she says next is just meant to educate us, not to debate. “Seven weeks and no invitation over. They don’t want to know us; we don’t need to know them.”

She actually means a lot more than she says. We’ve lived in enough places to understand the weight under a non-invite, or a failure to say hello, or the silence that follows when Dad introduces “Lu, my wife,” or Mom points to, “Jay, my husband.” Maybe it’s because “Lu, my wife,” has at times been described as abrasive, or “Jay, my husband,” has had to call far too many newspapers “his” newspaper to be considered a real newsman. Maybe it’s because “the Roth family” is a Jewish one, or maybe it’s because our house is older, or our cereal is off-brand, or our license plates are from another state, or our accents don’t quite match this side of the country. What we know by now is that “We don’t need to know them” is Mom’s way of protecting us from what people say when they’re trying to be polite, or what they don’t say when they’re trying not to be rude.

This isn’t the conversation I want to have tonight, though. Not any night really, but especially not tonight. I just want to get out the door before I give myself away.

“I’ll talk to them, okay?” I say, and Mom makes a pssht sound.

“Don’t bother,” she says, but she says it with a little singsongy voice so I can tell she’s not too upset. Not at the moment, anyway. She’s deep in the throes of her research now. I can tell by the way she keeps cracking her knuckles.

“Don’t be too late,” Dad says, but he’s smiling at Mom like he always does. My backpack and the amount of time I spend across the street are already distant memories.

The Petersons’ front door is open a crack, and I look around for anyone in the yard. It’s empty, though. In fact, the whole house seems quiet.

I knock softly on the door before opening it a little wider. “Hello? Aaron? Anyone there?” Then, a little softer, “Mr. Peterson?”

I’ve seen less and less of Aaron’s dad lately, a development I couldn’t be happier about after our encounter in his study I still haven’t been able to find again, even in the daytime, not that I’d want to. Stranger than that, though, is the way no one else in the family seems to bring up his increasing absence. It’s like he’s sort of just … fading away.

I hover by the door for a minute before pulling out Aaron’s note.

I check my watch. It’s 5:03.

Normally I’m not such a stickler for time, but I’m more nervous for this prank than I’ve been about the others. Maybe it’s because I haven’t had an opportunity to test the synthesizer with another audio system. Maybe it’s because I’ve been on edge ever since that night at Aaron’s. I tried asking Aaron about it in the morning, but I don’t really know what it was I saw. Whatever it was, one thing was clear: Mr. Peterson sees something in Aaron, and judging by Aaron’s presence in all those pictures, he sees something in his dad, too.

What that is, I can barely begin to guess, but it has something to do with Golden Apple Amusement Park.

I look at my watch again. 5:05.

“Mrs. Peterson?” I try again, then knock a little louder on the open door. “Uh … I mean Diane?”

This is definitely an intrusion. Aaron and I might have had solid plans, but that plan didn’t include me strolling through his house when no one’s here. The door is open, though. Maybe Aaron meant for me to come in.

I’m almost to the kitchen before it dawns on me that something could be wrong.

I turn in every direction—the kitchen, the stairway, the three hallways that lead to different corners of the house, then back to the open front door.

“Okay, I’ve seen all I need to see,” I whisper, resolved to give Aaron a hard time later about chickening out.

I turn back toward the door and straight into the broad chest of a towering Mr. Peterson.

“Aaron’s not here.”

I back up so fast I bump into the couch, nearly falling over it.

“The door was open,” I say stupidly.

Mr. Peterson doesn’t say anything. He just looks at me. No, that’s not right. He looks through me. I bet he could see what I had for lunch. Not for long, though, because I’m about to lose it.

“I … uh … I called for—”

“Aaron’s not here,” he says again, and this time it sounds a lot more like Get out of my house before I melt you into a human pile of wax with my death-ray eyes.

“Right. Okay. Absolutely. I was just on my way out.”

I babble all the way to the door, closing it so fast that I catch my heel and scrape the skin, but I hardly feel the sting as I skitter across the street, eyes over my shoulder, waiting for Mr. Peterson to come lumbering through the door and lunging toward me. I’m to the sidewalk when I allow myself to run through what I saw—Mr. Peterson was in his usual argyle sweater, but something was very wrong. His mustache was curled so crisply that the tips practically touched his eyebrows. He had that gunk on his hands again, but this time, he’d smeared it on his pants, too. His hair was a mess, and from the smell of him, I’d guess he hadn’t showered in a few days. And there was something else, something truly unsettling.

He looked scared. No, scratch that. He looked terrified.

“Where’ve you been?”

I spin hard enough that this time, I do feel the sting of my heel. I buckle under the burn and look down to see that I’ve started bleeding through my sock and all over the back of my Vans.

When I look up, Aaron is leaning against the streetlight looking bored.

“What do you mean ‘Where have I been?’ Where have you been?” I ask, and it comes out a little angrier than I mean for it to, but my shoes. These are actual Vans, not knockoffs. I was so lucky to get them for my birthday last year—Dad got a nice bonus for once. But now they’ve got blood on them, and why the heck wasn’t Aaron where he said he’d be?

“Whoa, whoa,” he says, putting his hands up in surrender. “I didn’t realize the plan was firm.”

“Seriously?” I say, folding the heel of the canvas under my foot so I can minimize the damage.

“Jeez, sorry,” he says, and it’s not enough. I’m mad at him for acting like it’s no big deal. Maybe it’s more than that. Maybe I’m mad that the more I think I understand Aaron, the more mysterious his whole life seems.

“Hey,” he says, this time looking genuinely concerned. “This is gonna be epic.” I back down because he’s not wrong. This is going to be epic. The only thing that’s gotten me through trips to the natural grocer with my mom and Mrs. Tillman’s phony smiles and condescension is the thought of showing people what her fake enlightenment really is—a bunch of farts disguised to sound like caring. She isn’t Zen. She’s just plain old greedy.

I start off ahead of Aaron, still not totally over my frustration until he says, “Your Vans look cooler like that.”

Then I’m okay. Because he knew.

I shift my backpack to my other shoulder, and we take side streets to the natural grocer. We tell each other it’s so we won’t be seen, but really I think it’s because that’s the long way, and maybe I’m not the only one who’s more nervous for this prank.

“You remember the plan, right?” I say.

“Dude, it’s my plan. Of course I remember it.”

We agreed that I would be the one to distract Mrs. Tillman while Aaron hooks up the synthesizer. I should be handling the install, but it’s more believable that I would be looking for a birthday gift for my mom; Mrs. Peterson has already made her opinion of Mrs. Tillman’s store pretty known.

We’re almost to the store now. We wait for the rush-hour traffic of Sixth Street to clear, then Frogger our way through the straggling cars and parked vans outside of the natural grocer, hoping the loaded backpack isn’t a dead giveaway.

“Remember to disable the primary audio outlet first,” I say to Aaron.

“I know.”

“And you know to start the volume super low, right?”

“Right. Super low.”

“Because the synthesizer is three times as amplified as a normal audio system.”

“Uh-huh,” he says.

“So if you don’t start it low—”

“Dude, calm down,” Aaron says.

“You do realize we’re toast if we get caught,” I say. “More than with Farmer Llama. Like, burnt-to-a-crisp toast. Like, butt-on-fire toast.”

“Yeah, I get it. Flames and roasted nuts and all that,” Aaron says, but somehow, I feel unconvinced.

The little bell above the door announces our arrival at the natural grocer. Smoothly, Aaron slips the backpack from my shoulder and makes his way to the back of the store, snaking through the aisles with the more obscure products. Mrs. Tillman interrupts her own conversation with a customer and takes a moment to eye me. She didn’t see Aaron.

When she’s done extolling the benefits of wheatgrass to a skeptical-looking man, she turns her full attention to me.

“Hello …”

“Nicky,” I remind her, even though every time I’ve been in here with my mom, she’s reminded Mrs. Tillman that my name isn’t Mikey.

“Right. And what brings you in today?”

“I’m, uh, looking for a birthday gift for my mom,” I say, just like Aaron and I rehearsed.

“Oh!” Mrs. Tillman looks shocked, and I can feel myself getting defensive already.

“Do you have anything you could recommend?” I ask, pretending to look around at the shelves but really searching for Aaron. I see his head bobbing down the last aisle by the stairs to the office. The intercom is by the little window that looks out over the whole store from the loft.

“For your mother, you say?” Mrs. Tillman says, and a weird little smile creeps across her face.

“Yeah. My mom,” I say, pointedly, my full focus back on Mrs. Tillman because now I know what she’s getting at. “Is there something wrong with that?”

“No, no,” Mrs. Tillman says, and she’s terrible at faking sincerity. “I just didn’t think she was—”

“That she was what?” I can feel my face getting hot.

“Well, you know, the products I sell are for people who have reached a certain level of … enlightenment.”

“She has a PhD,” I say.

Mrs. Tillman smiles again. “What I mean is, one needs to possess more than academic intelligence,” she explains like she’s doing me a favor. Like there’s no way I could possibly understand.

I turn away so she can’t see how red my face is getting, or how my eyes are starting to feel wet. Then, as I blink the burning from my eyes, I see Aaron’s face in the office window above. He’s smiling and giving me a thumbs-up, and I think I’ve never felt more powerful in my whole life.

I turn back to Mrs. Tillman, voice steady.

“I’ll just look around. You’ve got customers,” I say, nodding to the small line that’s formed in the time since she’s been talking to me. There’s the man with the wheatgrass and a woman with twin kindergartners playing jump rope with the coiled aisle separators.

Mrs. Tillman leaves without excusing herself and scolds the kids for playing on the rope before reaching down to grab the microphone under the register.

“Cashier assistance” is what her mouth forms, but all that comes over the loudspeaker is the sound of Aaron’s juiciest, loudest, most earthshattering fart we could record after a night of Surviva bars and two hearts bent on class warfare.

A collective silence follows as we all process what just happened. The kindergartners are the ones to break first.

“Mommy, she tooted!” says the girl, laughing riotously.

“Say excuse me,” the little boy admonishes.

Color drains from Mrs. Tillman’s face as she starts to deny it, but her finger is still on the microphone’s button, and instead of “I did not,” her mouth farts again.

The twins squeal and clap at the performance while the mother tries to settle them. I look at the man at the front of the line.

“Must be the wheatgrass,” I say, and he sets it down so fast, the canister tips over and rolls down the aisle.

I look up at the office, but I don’t see Aaron anymore.

Mrs. Tillman pursues the wheatgrass down the aisle as the mother loses control of the twins altogether.

“Let me try!” says the boy, who reaches the microphone first.

He presses the button and releases another echoing fart, and the kids squeal and trade places.

“Mommy!” the little girl screams into the microphone, sending flatulence thundering across the store. A few more people I didn’t even know were in the store pop their heads up from the aisles like groundhogs, looking mortified, like they were the ones who’d let it rip. Then they turn their silent judgment on Mrs. Tillman, who’s still chasing the can of wheatgrass down the far aisle.

Right toward the stairs to the office.

I hear her before I see Aaron.

“You!” she says, and another fart tears through the store. The kindergartners have teamed up now, pressing their mouths against the microphone at the same time.

The speakers begin to crackle, and the elation I felt for one glorious minute turns to horror as I realize that the speakers are getting ready to blow. Aaron must have turned the volume up too far.

“I knew you two were up to something! You may have pulled one over on Betty Bevel, but not me. Not this enlightened soul!” Mrs. Tillman shrieks, chasing Aaron up the aisle, barely sidestepping the canister of wheatgrass.

“Busted,” Aaron hisses as he flies past me.

“Stop right there!” Mrs. Tillman screams, lunging after Aaron, but now I’m ahead of him, trying to pry the kindergartners off the microphone before they blow the speakers out.

“Wait your turn!” one of them says while the other bites my hand.

“Ah!” I pull my hand back just as the mother yanks him off of me, but the little girl is still at the microphone, scream-farting into the microphone as the speakers pop and crack.

Aaron jumps on top of the checkout counter to escape Mrs. Tillman’s wrath, but it’s not him she’s reaching for. Instead, she reaches under the counter and slams her hand on a hidden button. Alarm bells sound, and red lights flash, and suddenly a mesh gate closes over both entrances of the store.

I look at Aaron, and his wide eyes confirm what I really wanted him to deny—we’re cooked.

Between the synthesizer and the alarm, the speakers buckle under the pressure, emitting one earsplitting pop before dying under a fizzle of static. Magically, the alarm still blares from a backup system. A tap at the door catches Mrs. Tillman’s attention, and she rushes to let the guest in.

A tired-looking uniformed officer strolls in, hands over his ears, and surveys the store for what went wrong.

“These boys! Arrest these boys!” Mrs. Tillman screams, but the officer refuses to uncover his ears.

“Marcia, the siren, please?”

He nods to the register, evidently aware that Mrs. Tillman is paranoid enough to have installed a full-blown Fort Knox-level alarm system in her stupid store.

She hurries to the counter and types in a code, silencing the siren and stopping the red lights from flashing.

The officer takes a slow scan of the now-silent store, meeting the gaze of every shocked face until he comes to Mrs. Tillman, who has been waiting impatiently to speak, tapping her fingers on the countertop. The officer takes his wire-framed glasses off, drags his palm down his face, then slowly puts his glasses on again.

“Go on and tell me what happened, Marcia.”

“I think it’s obvious, Keith,” she says, and it strikes me that she and the officer are on a first-name basis, which at first grosses me out because I think maybe they’re dating or something, but taking one more look at Officer Keith, it’s clear there’s someone else in Raven Brooks who dislikes Mrs. Tillman as much as Aaron and I.

“Well, then pretend like it’s not clear to all of us,” he says.

“That lady farted,” says the boy who bit my hand.

“I did not—”

“It was the wheatgrass,” says the man at the front of the line.

“Nope. Surviva bars,” Aaron says, and the twins dissolve into giggles. Aaron starts to laugh, too, and I can’t believe it. We’re up to our eyeballs in trouble, and he’s laughing like a kindergartner?

“It wasn’t—Oh, for heaven’s sake,” says Mrs. Tillman. “These, boys, did something to my intercom system!”

She says “boys” like she doesn’t actually believe we’re boys. Urchins, maybe. Or aliens. Or meat products. Officer Keith looks between me and Aaron, then settles on me.

“Is that true, young man? Did you vandalize Mrs. Tillman’s intercom?”

“I, uh—it’s more like—it wasn’t …”

“I did it.”

The entire store turns to Aaron, and I’m too shocked to say anything for a moment.

“You did what, exactly?” asks Officer Keith.

“I blew out her speakers. I was the one. It was all me,” he says. “I guess the gas made me do it.”

“That’s not true,” I say, trying to understand why Aaron would take the fall, why he’s making so light of it.

“It is true,” he says calmly, like he’s lied a thousand times before.

“No, it’s not. Aaron, what are you—?”

“It was both of them!” Mrs. Tillman shrieks, and Officer Keith puts his hands up.

“Okay, okay, I think I’ve got a clear enough picture of what’s going on,” he says, looking back at the boy who accused Mrs. Tillman of farting.

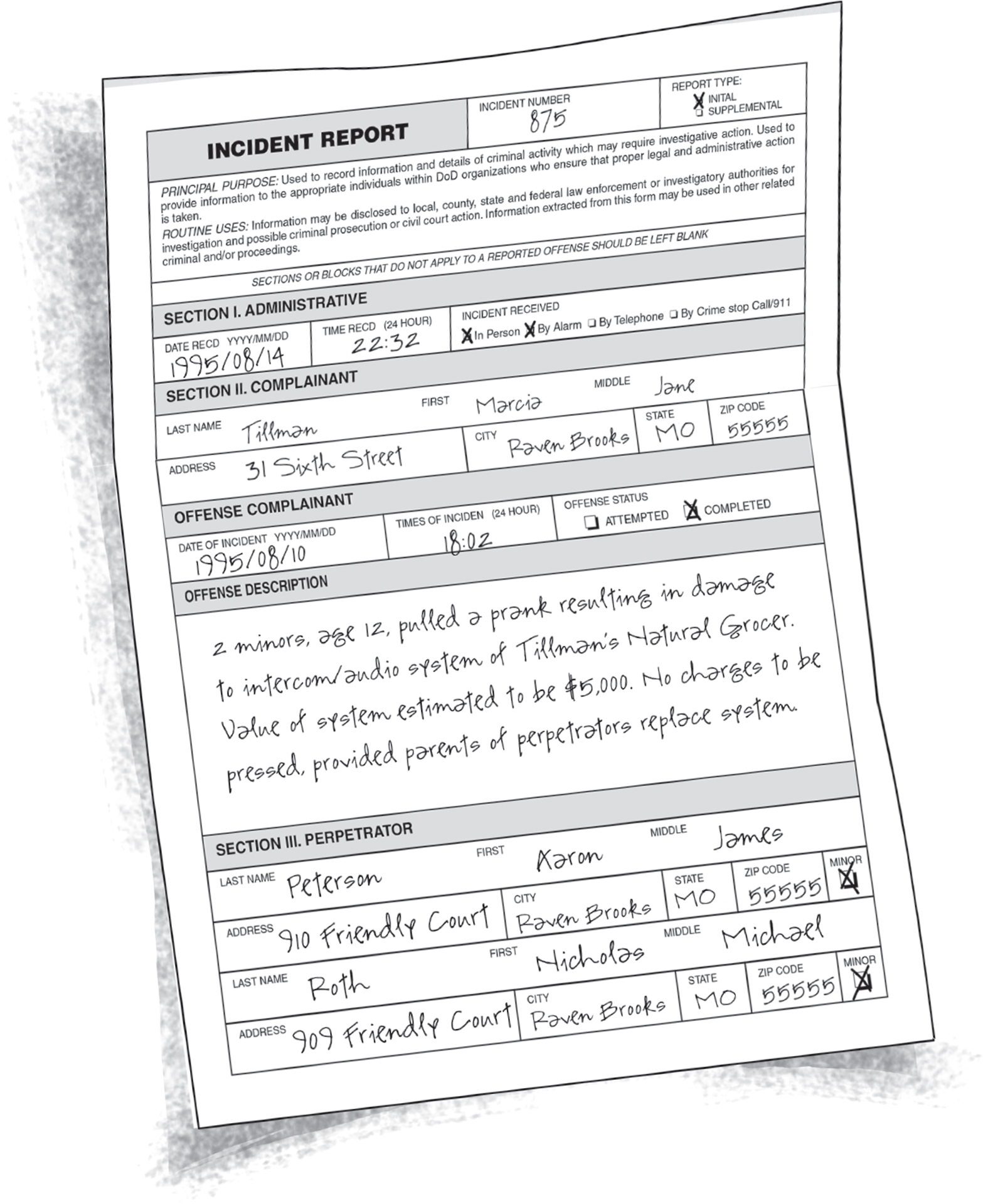

“Sounds to me like a couple of young gentlemen owe Mrs. Tillman a heartfelt apology and a new sound system.”

A rock sinks in my stomach at the thought of how much a new sound system will run, how I’m ever going to scrape together enough to pay for it. I can barely conceive of how I’m going to apologize to Mrs. Tillman.

I look at Aaron, but he won’t meet my gaze.

Our parents arrive at the same time, and this is how they finally meet—with Officer Keith between them, explaining that they owe Mrs. Tillman $5,000 for new speakers, describing the prank in enough detail to take all the magic out of it that it might have held after the seriousness of our offense had passed.

Mom and Mrs. Peterson catch each other staring a couple of times, I notice, and in those moments, they almost look like the same woman—strong and tired and angry, and not altogether surprised. Dad stands behind my mom, arms folded tight across his chest. Mr. Peterson stands beside Aaron, and this is the first time today I actually see fear in Aaron’s eyes.

I want to say goodbye to Aaron, but something tells me this would be the worst thing to do right now. I immediately regret not trying once we get in the car, though, because the first thing out of Mom’s mouth is:

“Well, I hope you had fun with your friend, because that’s the last you’re going to see of him.”

“Mom! That’s not fair!”

“You want to talk about fair? Let’s talk about what my signing bonus is going to buy, shall we? Do you suppose it’s a new washing machine?”

“No,” I mutter, rubbing the bruise on my hand where the kindergartner bit me.

“Are we going to get cable so you can watch all those ridiculous movies you’ve been begging me to see?”

I don’t answer.

“No? Oh, that’s right. We’re going to be buying Little Miss Namaste a new sound system so she can sell more eighty-dollar salt crystals to morons who can’t see how pretentious—!”

“Lu,” Dad says quietly, and she calms down immediately, not that she should.

Not only did I cause Mom to have to give money to a person who looks down on people like us, but I have no idea when I’m going to be able to hang out with Aaron again.

Tonight was supposed to be epic. I’ve never laughed so hard as when we were recording those farts for the synthesizer that night at his house. Now I can hardly remember why we thought this would be such a good idea.

I have never felt worse. Not after my grandma died. Not after that time I ate expired SpaghettiOs and thought I’d die of food poisoning. Not after we had to leave my favorite town, where I managed by some miracle to blend in. Nothing feels worse than being driven home with your parents explaining to you that you’ve disappointed them.

Nothing feels this bad.

Except being forbidden to hang out with the one person you’ve met in your entire life who maybe—just maybe—knows what it’s like to be utterly alone and not okay with it.

That feels worst of all.