I’ve held the gold-plated Golden Apple charm bracelet so many times, it’s starting to leave a green tinge on my skin. It’s like I’m waiting for it to break open and reveal its secret to me, to tell me what Mya wanted me to say that night. It would be easiest to just ask Mya, but predictably, I haven’t seen her—or any of the Petersons—since the funeral. Not on the front lawn. Not in the windows. Mr. Peterson’s car hasn’t moved. I’ve walked across the street half a dozen times, but I chicken out every time I’m about to ring the doorbell. Either I’m too afraid Mr. Peterson will answer or I’m too embarrassed that Aaron might answer and be mad that I haven’t done more to be there.

He told you not to come back.

That’s the justification that stops my finger midair over the doorbell. But isn’t that part of the messy process of grieving? My mom was a total wreck after my grandma died, and we knew for a while that she was coming to her end. Wouldn’t it make sense that Aaron was all messed up, too, that he was just saying things he didn’t mean? Wouldn’t a real friend try harder to be there?

There’s a fine line between trying harder and trying too hard, though.

None of this feels right—the leaving Aaron alone, the not being there for him, the sudden absence of any activity at all from across the street. Nobody seems in the least bit fazed that neither Aaron nor Mya have been seen outside the house for over two weeks.

“They’re probably just spending time together as a family,” said Mom when I brought her my concern.

“It’s important to give them their space, Narf,” Dad said.

I heard other excuses, too.

At the natural grocer: Seclusion is probably the best thing for them right now.

At the farmers’ market: That poor little girl must be devastated. She worshipped her mother.

At the university while I waited for Mom: I wouldn’t even know what to say, honestly.

It seems like everyone has a reason for avoiding the Petersons, now more than ever. I don’t even care about all the unanswered questions at this point. I’d settle for an afternoon of Surviva bars and lockpicking.

But I’m not better than anyone else in town, because instead of flashing a note to Aaron’s window or leaving something in his mailbox, I’m walking to a pep rally with Enzo.

As if Raven Brooks isn’t weird enough, apparently they also have a different tradition around football than pretty much every other school I’ve attended in every other town we’ve lived in. They hold their first pep rally two weeks before school even starts.

“Why is everyone in such a hurry to go back to school?” I ask, moping even though Enzo actually seems excited.

“Dude, aren’t you bored?” he says, walking faster than I want to.

Nope. “Bored” wouldn’t be the word I’d use.

“I just don’t get wanting to hang out on the football field and cheer for a bunch of jocks who would probably rather be punching people like me in the neck.”

Enzo looks at me, and I swear to the Aliens, it’s like it’s never occurred to him that we’re nerds.

“Why would they want to punch you in the neck?”

I have no idea what to say.

When we get to the high school, it’s already teeming with kids way older than us.

“Tell me again why this isn’t at our school,” I say, a wave of nausea rolling through me. It’s like the first day of school times a thousand. Everyone knows everyone. If Enzo leaves my side, even for a second, I’m sunk.

“Because technically, middle schoolers aren’t supposed to be here.”

“But all the middle schoolers come anyway?” I ask, so far not finding a single person who looks remotely close to twelve.

“Eventually, yeah,” Enzo says, nudging me through a crowd of guys in backward Raven Brooks Ravens hats.

“I want a good seat,” he says, and ushers me to the very first row of the metal bleachers.

Because nothing says cool like sitting in the first row.

“Can we maybe move back a little?” I plead, finding a perfectly invisible corner where I could easily make an exit once it’s discovered we’re LITERALLY THE ONLY MIDDLE SCHOOLERS at the high school pep rally.

“Shhh,” he says. “It’s starting.”

Why I’d need to be quiet is a mystery. The cacophony that drowns us out even before the team hits the field is nothing compared to the clatter of the marching band that follows, all of them decked out in their purple jackets and plumed hats. Enzo stands and cups his hands over his mouth, giving an earsplitting hoot to the band.

“Aren’t they great?” he says, beaming, and I can’t understand any of it. Everyone’s excited, but it makes no sense why Enzo is excited. Yeah, the band sounds great, and they have this synchronized wave thing that they do, but Enzo is looking like he’s ready to crowd surf, and there’s going to be no one there to catch him.

Except for the oboe player. Because she just blew a kiss at Enzo.

“Oh,” I say.

“Trinity. Isn’t she amazing?” he says, and I can’t help but smile at Enzo because I’ve seriously never seen anyone happier in my entire life. He’s like one big, pumping red heart. Maybe only Trinity looks happier, with her glistening braces and waist-length braids and glitter brushed across her dark brown cheeks. I would have pushed my way to the front row, too.

After the game—not a game but more of a scrimmage since Raven Brooks is the only town to even be thinking about a pep rally yet—Enzo and Trinity and I grab cheeseburgers because the sushi place is already closed.

“Right? Who wouldn’t pick sashimi over a greasy burger?” Trinity says, and if it’s possible, I’ve found yet another oddball in Raven Brooks. She makes me like Enzo even more. I’ve never seen a person so blissfully unaware of his dorkiness, and someone else be so accepting of that.

Except I kind of have seen that with my parents. Weird.

After dinner, Enzo bumps his fist to my shoulder.

“I’m gonna walk Trinity home. You good?”

I nod, and I mean it. I actually am good.

That is, until I pass the natural grocer on my way home, and memories of farting the afternoon away on Surviva bars with Aaron fill my brain and make me feel guilty all over again.

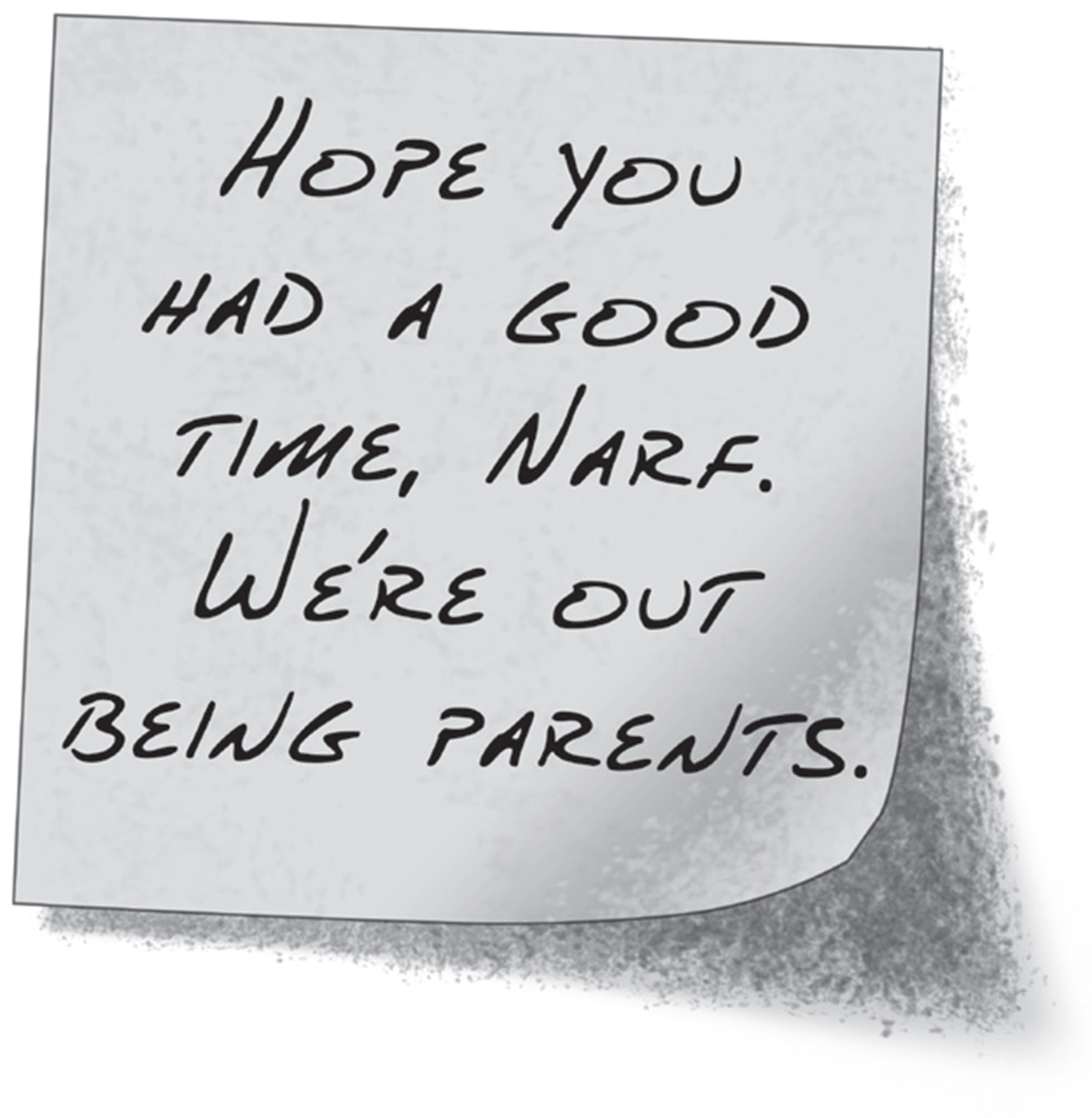

The house is dark when I get home, and I find a note from Mom and Dad.

I try to watch the Creepathon they’re showing on TV, but I just can’t get into it, not even when they feature the original Tooth. I realize that I’d held out the tiniest bit of hope that Aaron would make an appearance at the rally, even though I know that wouldn’t have been his scene even before his mom’s accident.

In bed, I stare at the ceiling and wonder why I’ve been so stuck in my head, so worried about what everyone else would think of what I’m doing or not doing. I’ve spent so much time trying to find a way to hide in every new town I start over in, I’ve practically forgotten that there are things people might actually think aren’t repulsive.

“This is stupid,” I say to the ceiling, and I get out of bed and grab a sheet of paper from my desk. In thick black marker, I write:

I roll the flashlight from under my bed—fresh batteries lighting it up bright again—and flick it on and off a few times at my window. Then I take a pillow and prop it under the flashlight handle until it holds the sheet of paper against the pane. I watch the window across the street for so long, my eyes get dry and heavy, and eventually I make my way to my bed, this time ready for sleep. I leave the note there, though.

* * *

I wake up screaming. At least, I must have been screaming because that’s the last thing I heard before I launched out of bed, my back soaked in sweat. My throat aches like I’ve been shouting. I stand up, ready to reassure my parents I’m okay, it was just another dream.

Just another wandering dream. There was something different about this one, though. Something very, very wrong.

I was in the grocery cart like always. I was high above the ground, but suddenly I wasn’t. Once again, I was wandering the aisles looking for help—my mother, my grandmother, someone to take me away from this place I knew I shouldn’t be. The aisles grew darker and darker until they weren’t aisles at all anymore.

They were hallways. Guided by candlelight, I walked along the hallways as shadows danced on the walls. I came to a room—empty except for a greasy paper bag. When I looked inside, I saw old take-out containers, two roaches crawling in and out of the to-go boxes. I backed away from the bag, but instead of finding my way out, I fell deeper until I was crawling again through the dark. I was alone, and then I wasn’t. I was on a chair, carrying me higher and higher above a sea of faceless bodies. I screamed for help, but nobody came. I pleaded to go home, but a voice crackled over the speaker I couldn’t see.

You already are home, it said.

Then the seat tipped me into the grasping hands of the bodies below. I was falling. Falling.

Falling.

Then I woke up.

I open my door, but no one greets me in the hallway. My parents are fast asleep, my dad’s toes twitching from under the covers. It’s still nighttime.

I close my door again, cupping my raw throat because it’s impossible that I hadn’t made enough noise to wake them, isn’t it?

I look to the window and find my note still pressed to the glass, my flashlight still propped behind it. As I creep closer to the window, though, I see that something is different from before. Aaron’s white curtain is billowing lightly through his own open window.

No, not open. Broken window. And not just cracked like it was before.

A jagged hole in the corner lets in a gentle night breeze, a hole I’m positive wasn’t there before I went to sleep. The curtain isn’t the only thing fluttering against the broken window, either. A white sheet of notebook paper dances in between the curtain and the glass. I squint, trying to make out what’s on the paper, but it’s no use. I’m too far away.

Grabbing my flashlight, I pop the screen from my window as quietly as possible, though apparently not even an earthquake would rouse my parents from sleep, so I might as well break the glass.

Climbing the shaking trellis, I pad across my grass and the street to Aaron’s yard, more afraid than ever because of that note. That broken window. Something is wrong.

Underneath his window, I watch the paper flap in the nighttime breeze, but I still can’t make out what it says. It says something, though, that much I can see.

“This is nuts,” I say to myself, but I know it’s not. “He’ll be fine,” I say to myself, but I know he won’t.

Still, what am I supposed to do? Climb the tree to get the note he clearly meant for me to see?

Yes, you’re supposed to climb the tree. That’s exactly what you’re supposed to do.

I’ve already resolved to go back inside to grab my shoes so I can get a better foothold on the trunk. But then a gust of wind kicks up, rattling the leaves above me and dislodging the notebook paper from the jagged hole in the window, sending it sailing into the middle of the street.

I chase after it, stepping on its corner right before it floats into a sewer drain. Crouching slowly, I unfold the lined paper to see Aaron’s handwriting.

The message is simple, but it would only be simple to me. It reads:

It might be enough to keep me away for good. He’s telling me to, in a way he knows only I’ll understand. It might be enough to forget all about Aaron Peterson and his sister and his mom and his dad and their sad, fraught lives. It might be enough, except for the broken window.

Except for the thick smear of dried blood that streaks a line across the notebook paper.

If it’s possible that Aaron really does make bad things happen, it’s equally possible that bad things can happen to Aaron, just like a bad thing happened to his mother. Just like something bad might be happening to Mya.

It’s only a note and a broken window, and it might be enough to keep me from thinking that something horrible is happening in the Peterson house. It might be enough, but in the end it’s not. Because the closer I look at that hole in the window, the clearer the scene becomes.

The smudge of blood along the jagged edges. The greasy black handprint left on the glass.

I stand in the middle of Friendly Court staring at Aaron’s scrawled words until the streetlight above me flickers, then gives up for the night.

Leaving me alone in the dark.