Friendly Margherita

Our Brush with an Anaconda

Whether she was really friendly or not is anybody’s guess, for Margherita was a giant snake, strong, supple, six metres long, and as thick as a man’s thigh. I jumped to the conclusion that she must be warmly disposed towards us simply because she had not crushed Mario in her coils. Admittedly, he was more than one third of her length – but, I mean, to any self-respecting boa constrictor, fresh from the jungle, he should have represented no more than a warm-up routine in her early morning workout. Don’t run away with the idea that I wished Mario any harm – he’s a friendly enough character himself – though when I later discovered that my partner in film was getting sixteen million lire from our Italian producer, and I only one, then sometimes I thought ... (well, maybe it is not necessary to tell all that one thinks) ... just leave it that now and then fantasies would erupt in my mind, in which the friendly Margherita assisted me in putting the squeeze on Mario ... I realise I am wandering off the point.

We were in Lima, lying on our beds in the Hotel Crillon, somewhere on the seventeenth floor of that skyscraper. Mario was telling me of his adventures with Walter Bonatti in the rainforests of South America: about the Indians, and an encounter they had had with some harlequin-coloured little frogs, which he only afterwards learned were the ones used for making lethal arrow poison ... and how Walter Bonatti narrowly escaped being crushed to death by an anaconda.[1] ‘By the way,’ continued my companion, ‘we will be needing to catch a giant snake of our own – they want us to film with one.’ He said this as if it would be as easy a matter as going into the woods for a kilo of mushrooms. I did not answer immediately: this was the way Mario had dropped surprises on me before ...

‘Is it that easy to approach a giant snake?’ I enquired at length.

‘No problem at all,’ Mario assured me. ‘The Indios bring them out of the forest all the time. A friend of mine, Pedro, can get us one easily.’ ‘Where does this Pedro live?’

‘In Iquitos, on the Amazon.’

‘Send him a cable, then, so that he can reserve a fine specimen for us.’ ‘No need, Professor,’ (that was my nickname from Mario), ‘when we get to Pedro’s he’ll have an eight-metre anaconda for us within half an hour. No tame one, either, one just brought in by the Indios. We’ll take it off into the jungle for a couple of days, let it go, then film it being caught again.’

‘And who’s going to catch this snake?’

‘Me,’ Mario replied airily.

Cheers, then, mate, I mutter to myself, knowing we’re in for some fun and games. Better watch out!

‘EQUIPADO CON RADAR’ it says on all the Peruvian airline planes, making them sound reassuringly modern. Even so, the aircraft are not always as reliable as this device suggests – that is, if one is to believe Mario, who is tightening his seat belt at my side. ‘Another one disappeared in the jungle, only recently,’ he tells me with relish. What, I wonder, is the radar for, then? These aircraft have to cross the Andes to get to the Amazon from Lima.

Below us, the dark red desert coastline slips away, then come isolated snow peaks, rugged rock faces and deeply cut valleys, a wild mountain area, the highest points of which are all six-thousanders. The further east we go, the more clouds pile up, increasingly filling the airspace above the endless green canopy which shimmers up at us through vaporous cotton wool. Down there, rivers loop like snakes – we catch the glint of water among the greenery, and spot little ox-bow lakes, cut off from the main stream. The clouds through which we are flying – we are reasonably low – are constantly transfigured by marvellous rainbows, half and full circles. ‘The Ucayali!’ Mario calls suddenly, pointing to the bends of a big river, one of the headwaters that feed the Amazon. ‘Soon we’ll see the Maranon as well,’ he continues. ‘Bonatti and I tried to navigate that from its source – but we didn’t make it. We took a bath.’ A thousand kilometres lay between Lima and Iquitos. Shortly before we get there, the two headwaters join. If you include the length of the Ucayali, the Amazon is 6,518 kilometres long. It is the greatest river of South America, the third largest on earth, and having the most extensive catchment area of all the rivers in the world.

We land on the small airfield of Iquitos in a violent cloudburst – within a few minutes we are soaked from head to toe. But, almost immediately, the sun shines again. Mario locates Pedro without any trouble, but he returns with a long face. ‘There’s been a cock-up with our snake,’ he murmurs. ‘Pedro says everything went with an animal shipment a few days ago. We have to find our own – I must have one at least eight metres long. It doesn’t matter if it’s a boa or an anaconda.’ Drenched in sweat, we repair first to the hotel.

A full day is spent traipsing around, sometimes wet, sometimes dry – between one cloud and the next, from one animal dealer to another. Iquitos is the main settlement of the Peruvian Amazonas area. Ships keep docking, navigating the giant river without difficulty: it is 1,800 metres (over a mile!) wide here.

Besides tourism, rainforest animals are an important source of income. It is incredible how many we see in a day: exotic fish of all kinds, circling in their aquariums, some big, but mainly an infinity of small flashing jewels – as if nature had overturned a treasure-chest, animating all the gems through some magical process. There is the squawking of hundreds of colourful jungle birds. Monkeys swing with grotesque twists of their limbs. A spotted jaguar hisses and jumps furiously against the bars of his crate. Fluttering on the outside of a big cage of birds with red shining head-feathers are others of the same species – trying in vain to get in ... the sad consequence of human intervention with the freedom of the forest; here at the jungle’s edge – because Iquitos is an island of civilisation – all these creatures face deportation. Do they sense that? All of a sudden I seem to feel the invisible shadow outstretched above so much colourful vitality. Our snake – I promise myself – will regain its freedom afterwards!

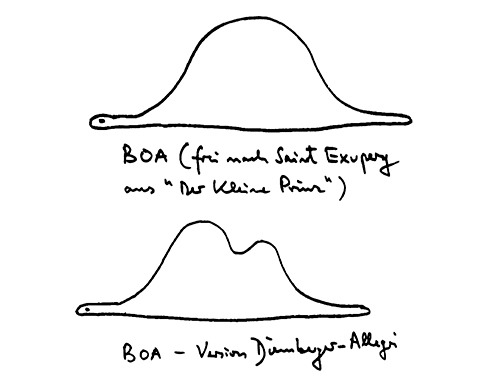

So far, however, we have no snake, neither boa nor anaconda. ‘Too small,’ Mario says every time an animal dealer shows us his best wares: pompously striped, patterned with curves, eyes, tangled lines, the markings seem to convey a hint of the immense power of these snakes. However passive they might look, is our two-man team equipped to cope with one of these creatures? Mario – the chief player (and in my thoughts, I already see him wrestling a writhing anaconda!) – and ... well ... me? I remember the Saint-Exupéry sketch of a well-satisfied boa, who has just swallowed an elephant, whole: the elastic-sided snake looks like a domed hat, viewed from the side, the brim on one side representing the tail; and that on the other, the snake’s head, which is relatively small. It is left to your imagination how so big a meal passed through such narrow jaws: the jungle is full of secrets ... Would a whole film team fit inside a boa? Or, having swallowed the larger of its two components, would the snake remain sated for the next few weeks and merely sleep? At least, I have never seen an ‘Exupéry-hat’ with two bumps ...

But the jungle, as I said, is full of secrets.

‘Mario,’ I ask prudently, ‘if I choose the right lens, couldn’t we make do with a four-metre snake?’

‘No way! She has to be eight metres,’ insists the ‘dominant half’ of our film partnership. I sigh, but then calm down: at any rate my partner, with all his extra height, is going to seem the ‘better half, in the snake’s eyes also!

Finally, we found her: A BOA CONSTRICTOR. She was asleep, and measured six metres. Her body, at its thickest, you could not encircle with your two hands – but her head was no bigger than a dog’s. She had wonderful markings, extending all over her scaly body, and Mario, well content, purchased her. The dealer assured us that she had just eaten a couple of mice. She really looked satisfied and peaceful – and I was about to put Saint Exupéry’s ‘hat’ from my mind, when I remembered the saying, ‘One swallow does not a summer make.’ Nor do a couple of mice fill a hat! But then, I said to myself, a snake from the Amazon could not possibly know this European proverb.

‘Let us call her Margherita,’ said Mario. Then we went down to the harbour to Pedro’s home.

Our boat divides the earth-coloured waters of the giant river. Above the green stripe of jungle on the opposite bank, which passes monotonously by, black thunderclouds build; here, in midstream, the sun strikes the boat with full force, but we do not notice it. We have a shady roof above our heads. Our craft is a primitive houseboat, which we have hired together with its three-man crew – dark-skinned locals, darker by far than the dark, earthy river, and dressed in an assortment of faded, well-worn garments. Pedro, Mario’s friend and our manager, is mestizo, the colour of his skin considerably lighter than that of the others. He has cultivated a small moustache, of which he is obviously very proud; his sunburnt face with the dark eyes is usually half hidden below a wide-peaked baseball hat – now he has lifted the brim. I can more or less understand his Spanish; he has just told me of a giant fish, very rare now. It looks like a monster and the local hunters kill it with a harpoon. Its name is the Paiche; I had already heard about it from Mario. Hunting this beast has so far never been filmed. The legendary predatory fish is very shy. Nevertheless, you can often find its exquisite scales, which can be as much as five or more centimetres in diameter, and prized here for necklaces ... usually strung with colourful seeds and snail shells. The bony tongue of the fish was – perhaps still is – used as a file by primitive Indian tribes. But the Indians hunt the Paiche mainly for its meat. It can reach four and a half metres and weigh as much as 180 kilos. To catch it, with just a harpoon, must be a violent and dangerous adventure. Will we ever see that fish? Now, the most important passenger on board is doubtless our Margherita! She is tied in a big jute sack, and unless you knew she was there, you would think we simply had a harmless load of sweet potatoes. It is understood that nobody will sit on that bag ... So, Margherita, are you still asleep?

Boa according to St Exupéry and the Diemberger-Allegri version.

All of a sudden, behind the boat grey bodies flash from the water, describe a majestic circle in the air, and disappear into the splashing flood, again and again, playfully. ‘Dolphins,’ says Pedro. ‘You often see them here.’ Five thousand kilometres from the mouth of the river where it flows into the Atlantic Ocean, here are tumbling dolphins! At the same time, entire islands of uprooted trees and water plants drift towards the distant ocean. The water plants have bright lilac flowers, which reminded me at first of periwinkle, but they have large bubbly airsacs and can, as I noticed during a rest ashore, continue to grow perfectly well on firm ground. A whole carpet of bladders and blooms cover water and land ... An amphibious plant, tailor-made for this mighty river, with its ever-changing water levels and extensive floods. Later on, a botanist will tell me that these are water hyacinths and they exist in many places across the world.

We travel well into the dark, through sunshine and pelting rain – most of the boats we encounter have roofs like ours. When we spot the glow of fires on shore, we tie up. Hospitable Indians allow us to pass the night with them. Dog-tired, we spread our mosquito nets above the wooden grille which forms the floor of one of the huts, all of which stand on four poles. As I slide into sleep, I still feel the continuous rocking of the water, and my heart glows at the sensation of shelter under a friendly roof, of people in the forest.

For three days we go upriver, following first the Amazon, then a smaller tributary, the Rio Maniti; our target is not only to film this snake, but as much as possible of its natural surroundings as well. Once here, on the Maniti, we do not meet any more boats and the walls of the forest on either side have crept closer. They have accepted us between them. In the evening we hack out a small space with our machetes, light a fire and sleep in hammocks – inasmuch as one can sleep amidst the multitude of animal sounds. It is like a living curtain descending and enfolding you into itself. Given several more pages, I could perhaps attempt a description, but it really would not help; I could never capture the unification of this flood of nocturnal sound, its togetherness, neither its synchronisation, nor the rhythmic, monotonous way it rises and falls in intensity. And this strange sensation of being part of it all.

It takes possession of you, courses through your veins, puts every fibre of your being under tension. Nowhere in the world is life created so abundantly, nor exists so closely together as here in the rainforest. Death is an ever-present constituent, but in the face of this thousandfold prodigality it has lost its horror, simply because here everything lives; death is only a smile, which in the moment of fading is already being born anew.

All my senses are alert because in the forest, so full of dangers, you are never permitted to dream. You need to be able to react quickly, to understand so much; it is a confusing world, one which needs your full consciousness to comprehend it. Even the apparent calmness of the forest people masks their ever-present vigilance. The dreaming, the smiling, the feeling at home in the jungle is a gift, but one which is offered to nobody from today to tomorrow.

A quick brightness invades the sky: the day returns, as suddenly as it went. In between lay eternity.

In the morning Pedro tells me that Margherita woke up, but a couple of mice had quickly pacified her. Our silent companion in the big jute sack would seem to be of phlegmatic disposition – so I think – but Pedro assures us the boa will become lively enough as soon as we open the bag at the forest margin. Several Indians will be needed for the safety of the film team, and we should choose a spot carefully, where the giant snake can be easily recaptured.

That day we arrive at a little Indian village, its huts standing on stilts in a clearing of the forest by the river’s shore. On the opposite bank are two further pile dwellings, near where we land. Pedro knows the old headman here, and after a warm welcome, it is obvious that this is where we’ll stay. Mario hopes also to be able to film crocodiles, and whatever else might turn up. We see a crocodile for a short while the next night – but not with a camera; Pedro, who feels obliged to shoot at everything, does not hit it, luckily. Instead, with two shots, he brings down a thorn-pig or tree porcupine from the top of a forest giant: the animal splashes into the water only a short distance from Pedro. It is a doubly valuable trophy with its spines of more than thirty centimetres long – like black knitting needles. The ‘pig roast’ which the chief’s wife prepares next day tastes great, despite the sinister fact that without its spines, the animal closely resembles a baby. It takes a great effort of will to bite into this grilled infant.

But you get used to it. Some things the Indians consume never cease to revolt you: bird-eating spiders, as big as a man’s hand; ants with fat honey-yellow abdomens; and creepie-crawlies of various kinds ... The ants taste of earth, and the spiders – well, I only managed to nibble at one leg; they are considered delicacies, but obviously I have not yet spent long enough in the forest. Porcupines from the grill, I can recommend, however, notwithstanding their appearance! The same goes for another speciality which from now on becomes our daily fare: fried piranhas! These notoriously bloodthirsty little fish still bare their teeth on the fire as if they wanted to strip an ox to its carcass, but of course they are harmless in this state. Even in the water, they pose only a limited threat – limited to the concurrence of blood being spilt. Given that, it is true everything happens with lightning speed: hundreds of little jaws with their razor-teeth snap and snarl, the water boils ... and soon only the bones of the victim are left. Even so, I cannot conceal the fact that on this trip up the Maniti, and later too, several times I saw Indios bathing without fear in the forest rivers. Mario swam across the Rio Maniti and for a long time in the middle of the river eagerly struck out against the flow. But Mario, well, is Mario. He is not to be put off by crocodiles or piranhas – whereas I prefer to keep a tight hold of the side of the boat whenever I cool myself in the river. I do not let my bare feet touch the bottom if I can help it, and never take off my bathing suit, having been warned by my companion about two unsavoury inhabitants of such waters: one is a fish which lies around on the riverbed and you run the risk of stepping on its poisoned spine; the other – covered in sharp bristles – deliberately seeks out orifices in the bodies of larger animals, in which to enter as a parasite, and from which it is almost impossible to extricate as its points are barbed like a harpoon.

You can take it from me that it had to be really hot before I let myself slip into the water.

Next day, we head upstream in a dugout canoe; we have been told of a little lake nearby, and Mario wants to see if we’ll be able to shoot our giant snake scenes there. This is a tipsy form of travel, and you have to pay some attention to equilibrium. In front of me an Indian is crouching with a short paddle, behind me sits Mario, and then Pedro, who also has a paddle. For some days the Rio Maniti has flooded its banks, enabling us to travel the whole way to the little lake in the canoe – even across the rainforest!

It becomes a strange journey.

Sometimes Pedro points to one animal or another which has saved itself by clambering into the high branches of a tree. Mostly, you can recognise them only by a sound, or movement. The treetops, and indeed the different layers of branches, are worlds in themselves, and after we leave the river and penetrate the drowned forest in our canoe, this becomes even more obvious. We zigzag between dense vegetation, then high tree-trunks. There is no noticeable flow, and everywhere smells of mud and the rotting leaves which are drifting on the water. I am filled with apprehension: even as a tenderfoot in the forest, I recognise how abnormal it is to be canoeing right across the forest floor like this. Besides gliding so mysteriously through the magic world of trees, you are moving in a different perspective, too, from at ground level. More than once I am tempted to ask the Indian in front of me to stop as we pass within reach of one of the fantastic red orchids with their darkly gleaming flutes, sitting on what would normally be the high branches … But it is just a whim; he passes by unmoved – to him it’s just an everyday thing. The water is getting shallower and the tree formations sticking out of the water become increasingly bizarre. Indeed, can you still call such contorted figures trees? There is no word for this multitude of tangled roots and trunks and stems, all from the same plant, holding each other in tight, inescapable embrace, as if the participants in a wrestle for life and death had suddenly become frozen by a spell. Colourful orchids and ferns peek from the crooks and hollows. Aerial roots dangle down, and lianas ... our dugout slides silently amongst these ‘sculptures’ – that is what they seem to be – groups of entangled Laocoon figures in ever-changing permutations, reminding me of the unsuccessful struggle of the father-priest and his sons of Greek myth, enmeshed by snakes. Sometimes the water gurgles gently at the dip of the paddle – the mirages of the tree-figures start to move and dissolve ...

In front of us appears a clearing: the lake! A circular surface, surrounded by the walls of ancient forest giants, black water, like a lead mirror. All around it is still. Beside the boat, where the sunlight falls into the water, a transparency of dark brown to olive green dissolves into the black of the depths. You cannot see the bottom, and no animals are moving in this water ... A sinister black hole.

Suddenly a swarm of parrots, with hellish squawking and whirling wing beats, flap like beginners across the gap in the forest ...

Mario decided this place was not suitable for our film. I had no objection. On the way back the man with the paddle sitting in front of me – speaking through Pedro – told us that a friend of his had died here recently, and he pointed vaguely to one of the twisted tree-sculptures: he was just ducking below the invasive canopy of leaves, when a little snake bit his head and it was too late to help him, it was a very poisonous one … The Indian’s tale went on vividly, and all of a sudden Pedro laughed, explaining to us, ‘The man did not suffer very much – he was drunk.’ When I think back, I do not like this day at all. But that is how it was.

Finding a suitable location for the film turned out to be difficult, but then luck stepped in. At the edge of the clearing a new house was being built – that means a couple of poles had been erected with two cross logs fixed between. These provided a platform where our helpers could keep guard while Mario attempted to catch the snake below them.

On the day in question, even he seemed uncharacteristically tense and thoughtful, more irascible – not his usual prankish self. He knew that at the critical moment he dared not stumble, knew that the snake would only be subdued if he succeeded in grabbing it with both hands just behind its head, and pressed firmly. Until this moment, he had to beware at all costs of getting into an embrace! A bite from the reptile would hardly be worse than that of a dog – but a clinch could spell death. Why such a giant snake loses most of its force if you succeed in getting the correct grip around its neck is a puzzle to me. But all snake handlers know the trick. And what Mario needed to help him was a long, forked stick. He quickly cut himself one from the forest with his machete. I would also keep one of these sharp knives within reach during the ensuing film session; if things went wrong, I could enter the fray – and fast! That such swift assistance might be necessary was understood by the Indians as well. Even though they are accustomed to catching anacondas and boas from time to time, it doesn’t always work out to plan – a man on his own is a weak opponent to a giant reptile!

I set up the big camera on its tripod about one and a half metres above the ground on the slatted wooden floor of a hut close to the one that was being built. I was four metres away from the ominous jute bag, lying now at the side of one of the new house-poles. From where I stood, I hoped to catch the whole scene with my zoom lens, secure a good overview from obliquely above and still be able to follow all the details of the action. In emergency I could easily leap down and weigh in with the machete – or, preferably, with my hand camera. Of course I felt some sympathy for Mario – at that moment he seemed a true hero to me, the essence of courage! And the sixteen million lire of his contract no longer seemed such a giant sum; safely atop my wooden grille, I felt quite content with my million. It is amazing how completely a metre and a half of extra height can change your perspective!

Not that you could say, of course, that you were really in a safe place up there: boas and anacondas are agile climbers and often found in trees.

The closer the moment approached, the more the white space of sky above the clearing seemed to disappear. The chattering of the natives died away. Even the forest itself stepped back ... all my concentration was focused on what would happen in front of me.

It was the same for Mario: we had discussed all the eventualities and clearly knew what had to be done. Three Indians were sitting on the cross-tie of the new house. They would pitch in only once Mario had succeeded in locking the head of the snake in his special grip – he had hoped they might have been on the ground sooner, but they refused. Pedro was standing with a machete in the shadows behind another hut, ready to rush to assistance ... We could start!

An Indian slowly and carefully loosed the string of the jute bag ... and disappeared behind the next hut. The bag was lying so that its opening faced the forest and Mario.

For some seconds nothing happens. Then the brown fabric starts to move: evidently Margherita has noticed the glimmer of light penetrating the darkness of her prison. Slowly, hesitantly, she pushes her head into the open, as if dazzled by the brightness of the day.

I watch Mario: his face has frozen to a mask, his black eyes fixed, immobile, his glance nailed to the slowly emergent boa five paces in front of him. He has crouched forward slightly, like an animal about to spring ... in his right hand he holds the two-metre pole with its forked end. Margherita suddenly stops. Has she noticed Mario? A forked tongue appears and flickers several times in front of the brown head with its shiny scales, licking the air above the ground. It is as if she is checking for hidden danger, and warning anybody from preventing her return to her forest. Mario still arches forward like a statue, ‘frozen’ in the sticky heat, sweat running down his face, eyes riveted on the motionless snake. In the shade of the hut’s roof, I too am bathed in sweat over my whole body – from excitement, from heat, from the effort of filming, from the concentration on what was about to happen next.

All is still and I can feel everybody holding his breath – even the Indios on the log; suddenly Margherita’s decision is clear: with an agility and speed I could never have credited to a giant snake, she shoots towards the forest, not by the shortest way, but in a sideways loop, to outreach Mario ... already I see her escape!

But Mario is not to be caught off guard: with a quick bound he blocks her path, standing in front of her once more, ready to thrust down the raised forked stick ... And Margherita? Without hesitation, she adroitly changes direction, in a way which makes it impossible for Mario to realise his intention: her head slides back over the coils of her body, so that if Mario were to dive for it now, he would surely be caught in a suffocating grip. His situation has become unexpectedly tangled – taut and tangled in every sense of the words! He circles the sliding spirals at a respectful distance, yet close enough to take advantage of the moment when Margherita, in whatever direction, makes another break for the forest ...

The boa has become slower now. Or is it simply an illusion caused by the many overlapping, overlooping coils of the scaly body? Now, at last, the giant snake must have understood that Mario is her enemy ... more than a mere obstacle on her way to the forest … slowly, she now slides directly towards Mario, whose face betrays that he has understood ...

Does he falter? Will he keep his nerve? Step by step, he retreats slowly and I see his hand clenching the stick so tightly that the knuckles have gone white – obliquely beneath me I hear the rustle of a sudden move as Pedro draws in from the side, but my full concentration is with Mario: he has lifted the forked stick and brings it down with all his force. Into the sand. He has missed the snake’s head! The reptile makes a sudden move – Mario pants, he has lifted the stick again, I see how he trembles with tension in this uneven duel. He knows that he is not allowed another mistake like that! Again, he thrusts down – and this time he gets the fork exactly above the neck of the boa, nailing the head of the mighty animal to the ground. The six-metre scaly body starts to wind like a giant screw – a terrible sight ...

Everything then followed at such flashing speed that it is all but impossible to describe it in sequence. A confusion of events, simultaneous, one after another and overlapping between: I see how Mario, hand over hand, comes down the stick as quick as a flash to the head of the snake. There comes a rough yell, from Mario or Pedro I cannot tell which. The Indios slide down from the log. Mario, having successfully secured the neck of the snake, now grips the boa tightly behind her head and, with all the strength of his arms and fingers, presses as hard as he can. He holds her head sideways now, half a metre above the ground. The Indios collect the still-writhing spirals of the reptile – but it is as if the energy behind the immense power of the animal has vanished under Mario’s grip. Working in fours, the men now drag the snake to a large basket. I draw breath, but mentally only, because my filming goes on – it is truly unbelievable how the men succeed in stuffing the coils of the thick body into the basket, beginning at the tail. At last, Mario, with one swift gesture, tosses the head in on top of the giant skein – he had been holding the boa ‘in grip’ all this time. Swiftly, the lid is slapped over the wickerwork and tied securely. To me, it is inexplicable why such a strong snake does not simply burst or bite through a jute bag or a basket. But Pedro has repeatedly assured me that, cut off from daylight, these animals immediately curl up, as they would in nature in a hollow tree. Nobody has ever thought with the mind of a snake. I take a breath. Mario sinks exhausted on to a rush-mat: he is running with sweat, marked with strain.

‘You did that well,’ I tell him.

He nods and pants. After a pause, he suddenly says, ‘And you? Did you do your bit well?’

The events of the last ten minutes flash past my mental eye. Exciting scenes, certainly an enthralling story ... but every conscientious cameraman knows that you can never have enough material; such a truth one should not hide, not even in the case of a giant snake ... ‘Fantastic scenes,’ I reply, seeing Mario visibly relieved, then – after a pause – I add, ‘All the same, I could do with a couple of close-ups with my hand camera.’ Silence.

‘Are you serious?’ Wide-eyed, Mario looks at me as if I’m a lunatic.

‘You can never have enough material,’ I insist, according to my conscience, and then I add with a benevolent voice, ‘You can rest for a while!’

What Mario thought I don’t know – at any rate, in the end he said, ‘Okay, once more!’

Secretly, I want to add, at the back of my intention was the hope that Margherita might this time perhaps succeed in reaching the forest. I did not expect Mario to prevent her with the same resolution as before. But I was wrong: Mario subdued the snake a second time with his special grip! This time I was really close with my hand camera, ‘skin-close’. Nevertheless, it all went so fast that I still needed one more take. After that, we were all exhausted. And poor Margherita? She had gambled away her third and last chance of freedom.

We stayed on a few more days in the jungle. We filmed the Indios, orchids, and several other things. Finally, we returned to Iquitos. And Margherita?

Despite my protestations, Mario had presented her to the Indios as a gift. They killed and ate her. Mario said, ‘We would have committed an unforgivable sin in their eyes if we had let her go.’

One of the laws of the jungle is never let yourself fall into the power of another.

I know this story of Margherita could have ended differently. Perhaps in a zoo in Europe, if we had brought her back to Iquitos. In those circumstances, I think what really happened was better. But why did we not let her go somewhere on the way back?

She had been promised to the Indios – and, once more, the rules of the humans prevailed over the rights of the animal.

***

It would be a pity not to tell how things went on with Mario …

We never did work together again. Not because of any flaws in the films we made. Well content with our success, we returned to Milan after our magic carpet had carried us 30,000 kilometres around the world. But there was a big catch to Mario’s next project: not that we were supposed to spend a day with crocodiles on a sandy islet in some African river; nor even that on Kilimanjaro I was temporarily to pass my camera to my companion and perform a stunt as the star of the show – the script requiring one of us to fall over the edge of a snow or ice face (not to the bottom of course, we could use a rope. That was more my department, Mario said. It would be better for him to hold the rope). No, the real snag was that at the very start of the journey Mario wanted us to penetrate the Danakil Desert of Ethiopia. This, he hoped, would bring us into contact with an unchanged aboriginal tribe with some pretty strange habits. He had some telling photographs of women wearing necklaces made from the highly prized ‘noble parts’ of enemies of the tribe. This, I have to confess, did not endear these people to me. It may well be that they had now abandoned the practice, as was said, or that none of their trophies had ever come from Europeans ... but it was enough: I had the uncomfortable feeling that my beloved Arriflex was not all I might lose there. Bloodthirsty stories abound in Ethiopian history: it is said that during the Abyssinian War some 3,000 Italian prisoners were emasculated! Of course, that was a good while ago now, but even in 1969, when I traversed the highlands of Semyen just to the west of the Danakil, we heard from a very reliable source of one such act of revenge at the end of a fight between two locals. Mario, intrepid to the core, made out that his ruling principle in life would be compromised if he did not attempt to seek out this tribe, but by the time I had come to terms with the idea, and wanted a contract to cover all risks, Mario became suspicious. It rubbed him the wrong way, and when our wives then entered the argument, he became even more furious. One day I heard he was about to leave with a different partner. It wounded and grieved me, but I rang him to wish him good luck, even so.

Mario and his companion crossed the Danakil Desert, were captured at one stage, but got free again. Destiny caught up with them on Kilimanjaro, where they were forced to bivouac in a terrible snowstorm at almost 6,000 metres. The end was bad – not for Mario, he has nine lives, but his companion had to be flown back to Europe with very severe frostbite. Mario called off the rest of the journey.

One fine day I was sitting in a pizzeria in Rome with Carlo Alberti Pinelli, a film director who wanted to visit the Indians at the source of the Orinoco River. Turning round, my eye was caught by an unusually lengthy corduroy suit, topped by a small rounded head. The man had his back to me, but that bristly haircut … the ostrich! It was indeed Mario. We had a pizza together soon afterwards and Mario told me that he was planning very shortly to parachute into the rainforests of South America. He believed he had finally discovered the lost city he had been hunting for so long. He said this with that same nonchalant smile with which he had once told me we were to capture a giant snake. It must make some difference, I think, if your grandmother comes from the Mato Grosso.

Perhaps I should add, by the way, that both of us ordered a Pizza Margherita.

1. There are known cases of anacondas swallowing fully grown Indians (Grzimek’s Tierleben (Animal Life). Whilst anacondas can reach a ‘guaranteed’ length of eight-nine metres, a boa constrictor only grows to 4.5 metres according to all the books. Our six-metre-long ‘Margherita’ belonged at any rate to the family of the boa snakes, even if it might have been another kind of anaconda. The animal dealer in Iquitos said it was a boa constrictor.[back]